This sample Ethics of Psychological Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of psychology research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

To do the best research and to give the best service to the community and to the profession, investigators need to behave ethically. Much has been written about the ethics of research in the behavioral sciences. For research in psychology specifically, the guidelines are set forth clearly in Section 8, Research and Publication, of the American Psychological Association (APA) Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct (Ethics Code; APA, 2002). It was specifically designed to meet “ethical challenges in the new millennium” (Fisher, 2003, p. xxv). Childress, Meslin, and Shapiro (2005) call the APA Ethics Code the best-known ethics code for the conduct of behavioral and social research (p. 265). Although it can be supplemented by other documents, the Ethics Code is the foundation for this research-paper on the ethics of psychological research.

The Ethics Code consists of 10 sections. Within Section 8 there are 15 standards, the first 9 of which specifically refer to research, with the last 6 covering publication of research results. Of these, only one refers to psychological research with animal subjects. The standards are preceded by five general ethical principles that underlie the standards in the code and are aspirational in nature: beneficence and no maleficence, fidelity and responsibility, integrity, justice, and respect for people’s rights and dignity (see Figure 12.1).

These principles are considered to be the moral basis for the Ethics Code, and are similar to those well known in bioethics (Beauchamp & Childress, 2001).

In applying the standards of the Ethics Code to specific situations in research, often the correct answer is not readily apparent. The investigator then needs to apply the general ethical principles to aid in decision making, after which she should consult a colleague and then document the process.

History

The protection of human participants is a huge issue in research. It was not always so.

One need only look to the egregious use of Nazi concentration camp prisoners for biomedical “experiments” during World War II or to the poor African American men with untreated syphilis recruited by the United States government for a study of the illness in the 1940s to understand that the rights of research participants have been frequently and flagrantly ignored. The Nuremberg Code, written during the Nuremberg War Crimes trial, is considered to be the first code of ethics for research with human participants. See Capron (1989) to review the Nuremberg Code.

Principle A: Beneficence and Nonmaleficence

Psychologists strive to benefit those with whom they work and take care to do no harm. In their professional actions, psychologists seek to safeguard the welfare and rights of those with whom they interact professionally and other affected persons, and the welfare of animal subjects of research.

Principle B: Fidelity and Responsibility

Psychologists establish relationships of trust with those with whom the work. They are aware of their professional and scientific responsibilities to society and to the specific communities in which they work. Psychologists uphold professional standards of conduct.

Principle C: Integrity

Psychologists seek to promote accuracy, honesty, and truthfulness in the science, teaching, and practice of psychology. In these activities psychologists do not steal, cheat, or engage in fraud, subterfuge, or intentional misrepresentation of fact. …In situations in which deception may be ethically justifiable to maximize the benefits and minimize harm, psychologists have a serious obligation to consider the need for, the possible consequences of, and their responsibility to correct any resulting mistrust or harmful effects that arise from the use of such techniques.

Principle D: Justice

Psychologists recognize that fairness and justice entitle all persons to access to and benefit from the contributions of psychology… .Psychologists exercise reasonable judgment and take precautions to ensure that their potential biases and the limitations of their expertise do not lead or condone unjust practices.

Principle E: Respect for People’s Rights and Dignity

Psychologists respect the dignity and worth of all people, and the rights of individuals to privacy, confidentiality, and self-determination. Psychologists are aware that special safeguards may be necessary to protect the rights and welfare of persons or communities whose vulnerabilities impair autonomous decision making. Psychologists are aware of and respect cultural, individual, and role differences, including those based on age, gender, gender identity, race, ethnicity, culture, national origin, religion, sexual orientation, disability, language, and socioeconomic status.

SOURCE: APA, 2002.

Table 12.1 The general principles from the Ethics Code that guide and inspire psychologists in all their work

In 1974 Congress passed the National Research Act, which created the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. It consisted of 11 people who were charged with developing ethical principles and guidelines for research involving human participants. This commission produced the Belmont Report (1978) in which the principles of justice, beneficence, and respect for persons (autonomy) were set forth. Sherwin (2005) notes that the Belmont Report “cites the ‘flagrant injustice’ of the Nazi exploitation of unwilling prisoners and the Tuskegee syphilis study as evidence of the shameful history of research abuses” (p. 151). According to Jonsen (2005), “If research involving human persons as subjects is to be appraised an as ethical activity it must above all be an activity in to which persons freely enter” (p. 7). Thus the central importance of informed consent was established.

The first APA Ethics Code was published in 1953. Throughout its 10 revisions, the goal has been to be to define the moral standards and values that unite us as a profession and a discipline that both treats and studies behavior.

The Institutional Review Board

To protect the human participants in research, an institution that applies for federal research funds is required to set up an Institutional Review Board (IRB; United States Department of Health and Human Services [DHHS], 1991). The IRB must consist of at least five researchers/faculty from a variety of disciplines who can review research at the institution with at least one member of the community who represents the public. Its mission is to ensure that human participants are dealt with in an ethical manner.

The Ethics Code references the IRB in Standard 8.01. 8.01 Institutional Approval When institutional approval is required, psychologists provide accurate information about their research proposals and obtain approval prior to conducting the research. They conduct the research in accordance with the approved research protocol.

Although some minimally risky pro forma class activities can be reviewed at the class or department level, any research project with risks to participants or which deals with vulnerable individuals such as minors or incarcerated people must have a full IRB review before commencing the research. Minimal risk is usually thought of as the risk inherent in daily living. The IRB reviews the investigator’s proposal with special attention to the experimental procedure, the informed consent process, the description and recruitment of the participants to be used, and the rationale for the research. The IRB then approves or disapproves of the research or provides information that can be used to modify the procedures proposed to more fully protect the participants.

For example, Martha’s senior thesis project is investigating how hearing a background of happy or sad music might affect person’s prediction of how well a pictured individual will do in a job interview. It appears that these activities are minimally risky; people listen to music and make implicit predictions every day. The college’s IRB reviewed this proposal. One member wondered what might happen if a participant had had a recent breakup with a boyfriend and was reminded of this event by the sad music. The IRB then recommended a routine statement in the debriefing that if one is affected adversely by the experiment one might visit the university counseling center. This comment was accompanied by the telephone number and e-mail of the center along with the routine contact information of the principle investigator, the investigator’s faculty sponsor, and the IRB.

Informed Consent

Informed consent must be given knowingly and voluntarily by a competent person to be able to participate in psychological research. The three requirements are therefore information, understanding, and voluntariness. The first of these three requirements is apparent from reading Standard 8.02.

8.02 Informed Consent to Research

(a) When obtaining informed consent as required in Standard 3.10, Informed Consent, psychologists inform participants about (1) the purposes of the research, expected duration, and procedures; (2) their right to decline to participate and to withdraw from the research once participation has begun; (3) the foreseeable consequences of declining or withdrawing; (4) reasonably foreseeable factors that may be expected to influence their willingness to participate such as potential risks, discomfort, or adverse effects; (5) any prospective research benefits; (6) limits of confidentiality; (7) incentives for participation; and (8) whom to contact for questions about the research and research participants’ rights. They provide opportunity for the prospective participants to and questions and receive answers.

Standard 8.02(a) list sets forth all of the information that a prospective participant is entitled to know about the research before making a decision about whether to participate. She should also have a clear understanding about what she will be asked to do in the study. This is particularly important if the research participants are to be students who either have a relationship with the investigator or are participating to obtain research points for a class assignment. Often introductory psychology students have an assignment to participate in a number of psychology experiments. For these students, having a definite understanding of the right to withdraw with no questions asked or to decline to participate at all, along with the right to collect any compensation, is crucial to the voluntary nature of informed consent. Since many students are skeptical about the procedures psychologists use to conduct research, a full explanation of risks involved, including mental stress is most important. Time to ask questions is needed to ensure full understanding.

The limits to confidentiality are also an important factor to be discussed during the informed consent period. Here Standard 8.02 is supplemented by Standard 4.01.

Standard 4.01 Maintaining Confidentiality

Psychologists have a primary obligation and take reasonable precautions to protect confidential information obtained through or stored in any medium, recognizing that the extent and limits of confidentiality may be regulated by law or established by institutional rules or professional or scientific relationship.

Participants may be asked to answer questions about their childhood, mental health, sexual orientation, or illegal activities, for example. This is obvious information to be kept confidential. If questions arise about the possibility of suicide and they are answered in a manner predictive of risk, an investigator might be obligated not to keep this information confidential. Contingency plans for this possible occurrence should be made with the college counseling center, for example. Indications that a child is likely being abused likewise need prompt attention. If a participant admits that she was abused and that she has younger siblings still at home, she needs to be aware beforehand that this is beyond the limits of confidentiality and must be reported to the local children and family services agency. It is recommended that participants be identified by using a random number so that they do not wonder if their data are recognizable or traceable.

Often anonymity is assumed because participants do not sign their name on a questionnaire. But any identifying questions or demographic information requested might make it possible to identify a particular person. For example, a research project is proposed where participants, students in the introductory psychology course, will be anonymous. Participants are asked to fill out a form indicating their age, sex, and race. Few students of nontraditional age or minority status are in the course, making it relatively easy to identify the person who says his age is 42.

Concerning the voluntary aspect of informed consent, it is important for participants not to feel any pressure to agree. Understanding the foreseeable consequences of withdrawing lessens this pressure. In addition, fully understanding the incentives for participation leads to a more rational decision.

Finally, participants need to be competent to consent to research. Competence is closely related to understanding, but adds a different twist. In the legal system, a person under the age of 18 is considered to be a juvenile. As such, a 17-year-old would not be considered competent to consent to being a research participant in most instances. To err on the cautious side, it would be unwise to ask a college student or anyone else under 18 to give informed consent, even though the person, if a college student, may be able to do so.

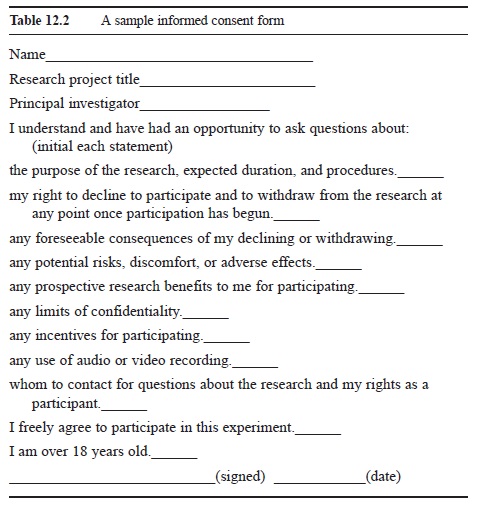

Table 12.2 A sample informed consent form

Table 12.2 A sample informed consent form

(c) When psychological services are court ordered or otherwise mandated, psychologists inform the individual of the nature of the anticipated services, including whether the services are court ordered or mandated and any limits of confidentiality, before proceeding.

(d) Psychologists appropriately document written or oral consent, permission, and assent.

Informed consent should always be documented. This is best done by asking the participants to sign a statement of understanding, although an electronic signature is acceptable. Alternatively, the investigator could document that the participant understood the statement and verbally agreed to participate.

Table 12.2 illustrates a sample informed consent form that covers all the bases.

A general informed consent standard from the Ethics Code, 3.10, states some additional considerations when seeking informed consent.

Standard 3.10 Informed Consent

(a) When psychologists conduct research or provide assessment, therapy, counseling, or consulting services in person or via electronic transmission or other forms of communication they obtain informed consent of the individual or individuals using language that is reasonably understandable to that person or persons except when conducting such activities without consent is mandated by law or governmental regulation or as otherwise provided in this Ethics Code.

(b) For persons who are legally incapable of giving informed consent, psychologists nevertheless (1) provide an appropriate explanation, (2) seek the individual’s assent, (3) consider such persons’ preferences and best interests, and (4) obtain appropriate permission from a legally authorized person, if such substitute consent is permitted or required by law. When consent by a legally authorized person is not permitted or required by law, psychologists take reasonable steps to protect the individual’s rights and welfare.

(c) When psychological services are court ordered or otherwise mandated, psychologists inform the individual of the nature of the anticipated services, including whether the services are court ordered or mandated and any limits of confidentiality, before proceeding.

(d) Psychologists appropriately document writ-ten or oral consent, permission, and assent.

In Standard 3.10 (a), the investigator is instructed to ask for informed consent “using language that is reasonably understandable” to the person. This would entail simplifying language that is more sophisticated or full of jargon than a person can be seen to understand. In addition, it would require someone who has less facility with English to be presented with the agreement in a native language, if appropriate.

The code also speaks to additional requirements for those potential participants who are legally incapable of consenting or legally incompetent to consent. If we consider this potential participant to be a 15-year-old adolescent, the code instructs the investigator to explain the study to the person, using reasonably understandable language. A person of this age could probably process all of the elements required by the code in Standard 8.02(a), so these would need discussing with the adolescent. Then the investigator would ask her if she would be willing to assent (agree) to being a participant, after first determining if it would be in her best interest to participate. Finally, the formal informed consent procedure outlined in Standard 8.02(a) would be presented to the parent or guardian. This same procedure would apply if the participant was a legally incompetent adult.

For example, John is interested in studying bullying behavior in middle school boys. He develops three kinds of questionnaires to be presented to the teacher, the child, and the parent. He prepares informed consent forms for each person which use the same words to describe the study and only differ in the words “my child cannot participate” for the parents, “I will participate in rating my students” for the teacher, and “I would like to participate” for the children. For the parents, he noted that they need sign the permission only if they did not want their child to participate. The IRB spent some time deciphering exactly what John was planning to do and whether this research plan could be modified to meet ethical standards. They questioned whether they should go so far as to redesign the study for John, or just disapprove the study. They decided that for this time they would only deal with the informed consent problems. They told John that the parents must sign an affirmative permission, not give it by default. They recommended that the permission slips not be sent home with the students or returned by the students for the possibility that this would put pressure on the students. They also disapproved of the wording of the permissions, feeling that many of the parents may not be able to read at the 12th grade level the permissions were written in. In addition, John did not appear to understand that the assent forms should be discussed with each student individually to insure understanding. They asked John to think about how a study of bullying behavior conducted by a college student might have some adverse impact on the child participants.

Distinctive Instances of Informed Consent

Intervention Research

When research is conducted in new kinds of treatment for mental health problems, special considerations apply. These are set forth in Standard 8.02(b).

8.02(b) Psychologists conducting intervention research involving the use of experimental treatments clarify to participants at the outset of the research (1) the experimental nature of the treatment; (2) the services that will or will not be available to the control group(s) if appropriate; (3) the means by which assignment to treatment and control groups will be made; (4) available treatment alternatives if an individual does not wish to participate in the research or wishes to withdraw once a study has begun; and (5) compensation for or monetary costs of participating including, if appropriate, whether reimbursement from the participant or a third-party pay or will be sought.

Thus, participants need to know that the treatment is experimental in nature, how the control group will be treated or not treated, how each individual is assigned to the treatment or to the control group, alternatives to the experimental treatment if the individual does not want to participate, and compensation issues. These additional components of the informed consent are particularly important because there is a likely possibility that the participants are from a vulnerable population, could easily be taken advantage of or exploited by the therapist/investigator, and might mistakenly believe that an experimental treatment is an improvement over the usual treatment.

Recording

Occasionally it is necessary to record (either audio or video) the behavior of a research participant. A participant has the right to know of the recording in advance and to decline participation. Standard 8.03 makes two exceptions.

8.03 Informed Consent for Recording Voices and Images in Research Psychologists obtain informed consent from research participants prior to recording their voices or images for data collection unless (a) the research consists solely of naturalistic observations in public places, and it is not anticipated that the recording will be used in a manner that could cause personal identification or harm, or (b) the research design includes deception, and consent for the use of the recording is obtained during debriefing.

Special Research Participants

8.04 Client/Patient, Student, and Subordinate Research Participants

(a) When psychologists conduct research with clients/patients, students, or subordinates as participants, psychologists take steps to protect the prospective participants from adverse consequences of declining or withdrawing from participation.

(b) When research participation is a course requirement or an opportunity for extra credit, the prospective participant is given the choice of equitable alternative activities.

Special care needs to be given to students, clients, or subordinates who participate in research. As noted above, precautions need to be taken to be sure that no pressure is placed on these individuals to participate. Standard 8.04(a) states that steps must be taken to protect students, for example, from a decision to withdraw or decline.

Standard 8.04(b) adds a further requirement. The question here is what is an equitable alternative activity to the course requirement? College students in the introductory psychology class are frequently used as research participants because they are convenient and plentiful. Their use is normally justified, however, by the educational value of learning about psychological research firsthand. An equitable alternative activity should take about the same amount of time and also result in learning about research. Possible examples include reading about how to design and carry out experiments, reviewing articles on empirical research, or even helping out with data collection. Most likely the students who actually do these alternative activities are those who run out of time to be participants or who need to do assignments on their own schedule.

For example, in Maggie Smith’s Psychology 101 class, students are required to participate in four 30-minute units of research. Alternatively, they may elect to review four research articles from the psychology literature. For this assignment students must locate an article and describe the participants, the procedure, and the results. Maggie decides that even though she dislikes the idea of participating in research because it disrupts her carefully planned child care schedule, she must participate because the reviewing of four articles is more difficult and much more time consuming. She does not give her informed consent voluntarily.

When Informed Consent Is Not Required

Standard 8.05 of the Ethics Code states,

8.05 Dispensing With Informed Consent for Research Psychologists may dispense with informed consent only (1) where research would not reasonably be assumed to create distress or harm and involves (a) the study of normal educational practices, curricula, or classroom management methods conducted in educational settings; (b) only anonymous questionnaires, naturalistic observations, or archival research for which disclosure of responses would not place participants at risk of criminal or civil liability or damage their financial standing, employability, or reputation, and confidentiality is protected; or (c) the study of factors related to job or organization effectiveness conducted in organizational settings for which there is no risk to participants’ employ-ability, and confidentiality is protected or (2) where otherwise permitted by law or federal or institutional regulations.

For example, Sally wanted to know if preschool boys played more roughly than preschool girls. She went to a park playground where day care teachers took their children for their daily recess play. She unobtrusively tallied the number of rough play incidents between boys and boys, between girls and girls, and between boys and girls. For these frequency data taken in a naturalistic observation no informed consent was needed.

Ignoring informed consent in school settings should be done very cautiously. Interventions or assessments that are not a routine part of the education of children should be consented to by a parent or guardian, although at times a school administrator will assume this responsibility on behalf of the children and parents.

Inducements

The voluntariness of consent can be affected by the inducements offered to participate. Typical inducements can be money, gift certificates, research points for a class requirement, extra-credit points for a class, and professional service. Excessive inducements can pressure a person to consent and affect its voluntariness.

8.06 Offering Inducements for Research Participation

(a) Psychologists make reasonable efforts to avoid offering excessive or inappropriate financial or other inducements for research participation when such inducements are likely to coerce participation.

(b) When offering professional services as an inducement for research participation psychologists clarify the nature of the services, as well as the risks, obligations, and limitations.

For example, if participants are recruited from students living in two college dorms, would $10 for an hour of participation be excessive? What about $20?

Debriefing

Standard 8.08 states,

8.08 Debriefing

(a) Psychologists provide a prompt opportunity for participants to obtain appropriate information about the nature, results, and conclusions of the research, and they take reasonable steps to correct any misconceptions that participants may have of which the psychologists are aware.

(b) If scientific or humane values justify delaying or withholding this information, psychologists take reasonable measures to reduce the risk of harm.

(c) When psychologists become aware that research procedures have harmed a participant, they take reasonable steps to minimize the harm.

Researchers ideally talk with participants immediately after the conclusion of their participation, giving information about the experiment and answering questions. This is what makes research participation truly educational. In addition, investigators can learn from participants about difficulties they may have had in understanding directions, for example. Research results can rarely be given at this time so researchers notify participants of where they can learn of the results and conclusions. This might mean sending participants an abstract of the results, or at least offering to do so, or posting a description of the study along with the results and conclusions on a bulletin board or Web site that participants can access.

Often a particular participant may be upset with an experiment. Procedures that would be quite neutral for some may prove to be disturbing for others. Should this be the case, the Code requires that the investigator take “reasonable” care to alleviate the harm. What is reasonable varies from one person to another and is difficult to define. In fact, it has a legal meaning that a jury of ones peers would find an act to be reasonable. Because it is unlikely, hopefully so, that a jury would ever be involved, a good substitute is to consult a colleague to confirm that one’s actions appear reasonable. This consultation should always be documented along with the informed consent. For most idiosyncratic reactions to an experimental procedure, referral to the university counseling center or a mental health clinic just to talk with someone is often recommended.

For example, Steve was asked to visualize and then view a movie of a crime committed by a mentally disturbed person. During the debriefing, it became apparent that the movie was deeply disturbing to Steve. The investigator, who had foreseen this possibility, discussed with Steve the arrangements that had been made for participants to debrief further with a psychology intern in the department.

The Special Case Of Deception In Research

Can a research participant ever give informed consent to be in a study where deception is involved? Reflect on this while reading Ethics Code Standard 8.07.

8.07 Deception in Research

(a) Psychologists do not conduct a study involving deception unless they have determined that the use of deceptive techniques is justified by the study’s significant prospective scientific, educational, or applied value and that effective nondeceptive alternative procedures are not feasible.

(b) Psychologists do not deceive prospective participants about research that is reasonably expected to cause physical pain or severe emotional distress.

(c) Psychologists explain any deception that is an integral feature of the design and conduct of an experiment to participants as early as is feasible, preferably at the conclusion of their participation, but no later than at the conclusion of the data collection and permit participants to withdraw their data.

Two types of deception study are the most common in psychological research. One type of deception study involves a confederate of the experimenter whom the participant believes to be someone else, perhaps a fellow participant. In the second instance, the participant is given false or misleading feedback about his/her work.

Consequences to the participant can range widely. Many participants, upon being dehoaxed or debriefed, have no reaction or are amused by the disclosure. Others feel duped, deceived, like they’ve been made a fool of, or emotionally harmed by the experience. Some feel that they cannot trust a psychologist/experimenter again. Some experience a loss of self-esteem. If some participate in another experiment, they try to figure out the real purpose of the research and thus are not naive participants again. The reputation of psychological research can be damaged in the eyes of participants.

Some deception research is relatively harmless whereas other studies can leave lasting effects on the participants. Consider the following two deception studies, the first of which is a classic involving a confederate of the experimenter, and the second, a more recent study, giving false feedback to the participants.

Some citizens of New Haven, Connecticut elected to participate in the obedience study conducted by Stanley Milgrim (1963). These participants were told that they were part of a study on the effects of electric shock on learning. They were not told that the real purpose of the study was to see how far a person would go in shocking a difficult learner. The “learner,” who just couldn’t learn, was actually a confederate of the experimenter, acting increasingly harmed by the “electric shock.” Surprisingly, the researchers concluded that a majority of everyday people would shock another person to the point of what they thought to be great injury, all in the name of science or in obedience to a researcher in a white lab coat.

Compare the Milgrim study with one over 30 years later. Kassin and Kiechel (1995) instructed participants to type letters read to them as fast as they could. They were instructed not to touch the “alt” key as this would spoil the experiment. In one condition participants were told that they had in fact touched the forbidden key and ruined the experiment. Several of these participants not only felt that they had destroyed the data but made up an explanation for how they had done so. The researchers concluded that, given the right conditions of interrogation, people can fabricate confessions and even come to believe them.

Applying Standard 8.07(a), it is first necessary to look to the significance of the scientific, educational, or applied value of the study. Assuming that the studies are of significance, it is required next to look at whether effective nondeceptive alternative procedures are feasible. Although this is controversial, assume that the two studies are of significance and that no nondeceptive procedures could have yielded these results. In Standard 8.07(b) we are instructed to contemplate whether participation in these projects could reasonably be expected to cause physical pain or emotional distress. Most people would agree that deciding to shock another person to the point of great physical injury is many steps above accidentally ruining an experiment. Today, it is unlikely that Milgrim could have had his study approved by his university’s IRB.

Finally, Standard 8.07(c) provides a remedy for the participant in a deception study. Upon dehoaxing, the participant may request that her data be withdrawn from the study. Thus she is saying that if I had been informed of the true procedure of the study, I would not have consented to being a participant.

Does this amount to informed consent? Note that the researcher in the debriefing does not need to offer to let the participant withdraw her data. The participant needs to come up with this idea on her own. In contrast, the Canadian Code of Ethics for Psychologists (Canadian Psychological Association, 2000, pp. 23, 26) states

In adhering to the Principle of Integrity in Relationships, psychologists would…

III.29 Give a research participant the option of removing his or her data, if the research participant expresses concern during the debriefing about the incomplete disclosure or the temporary leading of the research participant to believe that the research project or some aspect of it had a different purpose, and if the removal of the data will not compromise the validity of the research design and hence diminish the ethical value of the participation of the other research participants.

In the Canadian code, the researcher is to give the option of withdrawing data to the participant. With respect to the validity of the experiment, the argument can be made that this participant would not have consented to being in the experiment if she had known its true nature.

Another possible solution to the informed consent to deception research may be feasible in a setting where there is a very large subject pool. Prior to selection for any particular research participation, individuals put themselves in to one of two categories: those who are willing to participate in deception research and those who are not. Presumably those in the first category are on their guard for being deceived, making them somewhat more suspicious of the true nature of the research than those in the second category.

In addition, Veatch (2005) notes in reference to Standard 8.07 that “the American Psychological Association has long endorsed behavioral research on terms that violate both the Department of Health and Human Services regulations and the spirit of Belmont” (p. 189). Specifically this refers to the principle of autonomy in the Belmont Report and the precautions found in the DHHS (1991) regulations. Autonomy, the right to make ones own decision about participating in research, is arguably not respected in deception research.

Research With Animals

Much information that is useful for the understanding of human behavior or for the welfare of humans comes from research with animals. The utility of the research, however, does not justify the unethical treatment of the animal subjects. Many feel that because animals cannot ever give informed consent to research and may be physically injured by the research, very special care should be used to treat animals ethically if they must be used in research at all. Analogous to the IRB, the federal government also requires institutions using animals in research to form an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) to oversee the ethical treatment of research animals, including their acquisition and housing. The APA Ethics Code states,

8.09 Humane Care and Use of Animals in Research

(a) Psychologists acquire, care for, use, and dispose of animals in compliance with current federal, state, and local laws and regulations, and with professional standards.

(b) Psychologists trained in research methods and experienced in the care of laboratory animals supervise all procedures involving animals and are responsible for ensuring appropriate consideration of their comfort, health, and humane treatment.

(c) Psychologists ensure that all individuals under their supervision who are using animals have received instruction in research methods and in the care, maintenance, and handling of the species being used, to the extent appropriate to their role.

(d) Psychologists make reasonable efforts to minimize the discomfort, infection, illness, and pain of animal subjects.

(e) Psychologists use a procedure subjecting animals to pain, stress, or privation only when an alternative procedure is unavailable and the goal is justified by its prospective scientific, educational, or applied value.

(f) Psychologists perform surgical procedures under appropriate anesthesia and follow techniques to avoid infection and minimize pain during and after surgery.

(g) When it is appropriate that an animal’s life be terminated, psychologists proceed rapidly, with an effort to minimize pain and in accordance with accepted procedures.

Standard 8.09 is supplemented by the APA Guidelines for Ethical Conduct in the Care and Use of Animals (APA, 1997)

For example, Harriett, a university work/study student has been employed by Dr. Green in the neuroscience department to care for his laboratory rats over the weekends. She has been carefully trained by Dr. Green on the procedures to be used. At the last minute, Harriett has been given the opportunity to spend a weekend in New York City with a friend. She searches around for someone who will take care of the animals while she is gone. Robert, one of her classmates, agrees to feed the animals. Without knowledge of the feeding procedures, Robert feels that he can feed the animals double on Saturday and omit the Sunday feeding. While measuring out the food, Robert finds that the temperature in the lab is too warm for comfort, so he turns the thermostat down as far as it will go, fully intending to turn it back up when he leaves. On Monday, Dr. Green tells Harriett that she has spoiled his research with her carelessness.

Ethics Code Standards That Deal With Reporting Research Results

Standard 8.10 makes a definitive statement about the ethics of the dissemination of research results.

8.10 Reporting Research Results

(a) Psychologists do not fabricate data.

(b) If psychologists discover significant errors in their published date, they take reasonable steps to correct such errors in a correction, retraction, erratum, or other appropriate publication means.

In very few standards of the Ethics Code is there a statement that absolutely prohibits an action. The fabrication of data is one of those cases. If an error is make in the publication of data, psychologists have an obligation to publish a retraction in whatever form is appropriate for the purpose. The Ethics Code makes definite the unethicality of any kind of scientific misconduct.

In Standard 8.11, there is another absolute prohibition.

8.11 Plagiarism

Psychologists do not present portions of another’s work or data as their own even if the other work or data source is cited occasionally.

Plagiarism is a very serious offense. The taking of another’s words or ideas as ones own is the theft of intellectual property. This unethical usage also extends to the oral use of another’s words or ideas without crediting the originator. This is known as oral plagiarism.

8.12 Publication Credit

(a) Psychologists take responsibility and credit, including authorship credit, only for work they have actually performed or to which they have substantially contributed.

(b) Principle authorship and other publication credits accurately reflect the relative scientific or professional contributions of the individuals involved, regardless of their relative status. Mere possession of an institutional position, such as department chair, does not justify authorship credit. Minor contributions to the research or to the writing for publications are acknowledged appropriately, such as in footnotes or in an introductory statement.

(c) Except under exceptional circumstances, a student is listed as principal author on any multiple-authored article that is substantially based on the student’s doctoral dissertation. Faculty advisors discuss publication credit with students as early as feasible and throughout the research and publication process as appropriate.

Although the order of names on a multiple-authored article may seem unimportant, it is just the opposite. Those who are in a position of evaluating a person’s work, assume that the first stated author did more of the scholarly work than the second author did, and so forth. Normally, if each author’s contribution was similar, this fact is mentioned in a footnote to the authorship. It is also assumed that because a dissertation represents an original work of scholarship, an article based on a person’s dissertation will list that person’s name first or solely. Contributions to a publication in the form of collecting dates, running a computer program, or assisting with a literature review are normally given a footnote credit.

8.13 Duplicate Publication of Data

Psychologists do not publish, as original data, data that have been previously published. This does not preclude republishing data when they are accompanied by proper acknowledgment.

8.14 Sharing Research Data for Verification

(a) After research results are published, psychologists do not withhold the data on which their conclusions are based from other competent professions who seek to verify the substantive claims through reanalysis and who intend to use such data only for that purpose, provided that the confidentiality of the participants can be protected and unless legal rights concerning proprietary data preclude psychologists from requiring that such individuals or groups be responsible for costs associated with the provision of such information.

(b) Psychologists who request data from other psychologists to verify the substantive claims through reanalysis may use shared data only for the declared purpose. Requesting psychologists obtain prior written agreement for all other uses of the data.

Together Standards 8.13 and 8.14 deal with other aspects of scientific honesty. Data that are published more than once without a proper acknowledgment erroneously suggest that multiple data collections and analyses have been done. Sharing ones published data with a colleague for reanalysis is not only a professional courtesy, but also helps to ensure that the data have been legitimately collected and carefully and accurately analyzed. Clearly, one who requests data to reanalyze must not use these data as her own for research and publication purposes. A similar standard, 8.15, applies to reviewers for publication.

8.15 Reviewers

Psychologists who review material submitted for presentation, publication, grant, or research proposal review respect the confidentiality of and the proprietary rights in such information of those who submitted it.

The Future Of Research Ethics In The 21st Century

The general ethical principles that underlie the Ethics Code also provide foundational stability to the values of the profession and the discipline of psychology. It is unlikely that the 21st century will produce any more important values for psychologists than doing good, not harm; being trustworthy; promoting integrity and justice and respecting the rights and dignity of all people.

Ten versions of the Ethics Code were adopted between 1953 and 2002. With this background, one could confidently predict that the Ethics Code will be revised approximately nine times in the 21st century. Likely events to bring about such a modification would be changes in federal law, advances in technology, and political and social issues all of which can raise unforeseen problems with standards in the Ethics Code.

References:

- American Psychological Association. (1994). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

- American Psychological Association. (1996). Guidelines for ethical conduct in the care and use of animals. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved January 1, 2007, from http://www .apa.org/science/anguide.htm

- American Psychological Association. (2002). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. American Psychologist, 57, 1060-1073.

- Beauchamp, T. L., & Childress, J. F. (2001). Principles of biomedical ethics (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Canadian Psychological Association. (2000). Canadian Code of Ethics for Psychologists (3rd ed.). Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Author.

- Capron, A. M. (1989). Human experimentation. In R. M. Veatch (Ed.), Medical ethics (pp. 125-172). Boston: Jones and Bartlett.

- Childress, J. F., Meslin, E. M., & Shapiro, H. T. (Eds.). (2005). Belmont revisited: Ethical principles for research with human subjects. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Fisher, C. B. (2003). Decoding the ethics code: A practical guide for psychologists. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Jonsen, A. R. (2005). On the origins and future of the Belmont Report. In J. F. Childress, E. M. Meslin, & H. T. Shapiro (Eds.), Belmont revisited: Ethical principles for research with human subjects. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Kassin, S. M., & Kiechel, K. L. (1996). The social psychology of false confessions: Compliance, internalization, and confabulation. Psychological Science, 7, 125-128.

- Korn, J. H. (1997). Illusions of reality: A history of deception in social psychology. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- LeBlanc, P. (2001, September). “And mice…” (or tips for dealing with the animal subjects review board. APS Observer, 14, 21-22.

- McCallum, D. M. (2001, May/June). “Of men…” (or how to obtain approval from the human subjects review board). APS Observer, 14, 18-29, 35.

- Milgrim, S. (1963). Behavioral study of obedience. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67, 371-378.

- Miller, N. E. (1985). The value of behavioral research on animals. American Psychologist, 40, 423-440.

- National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. (1978). The Belmont Report: Ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research (DHEW Publication OS No. 780012). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Sherwin, S. (2005). Belmont revisited through a feminist lens. In J. F. Childress, E. M. Meslin, & H. T. Shapiro (Eds.), Belmont revisited: Ethical principles for research with human subjects. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. (1991). Federal policy for the protection of human subjects: Notices and rules. Federal Register, 46(117), 28001-28032

- Veatch, R. M. (2005). Ranking, balancing, or simultaneity: Resolving conflicts among the Belmont principles. In J. F. Childress, E. M. Meslin, & H. T. Shapiro (Eds.), Belmont revisited: Ethical principles for research with human subjects. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.