This sample Investigative Psychology Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Investigative Psychology (IP) is a subdiscipline of psychology developed by David Canter for the integration of a diverse range of aspects of psychology into all areas of criminal and civil investigation and legal processing (Canter 1995b, 2011; Canter and Youngs 2009). It considers all forms of offending action from arson, stalking, and robbery to murder, rape, or terrorism, exploring the psychological processes involved in the detailed actions and the influences on and characteristics of perpetrators. The starting point for such studies is the operational challenges that arise during investigation or in court, but the models and theories that have emerged inform the general psychological understanding of offending action and offenders.

The discipline may be understood in terms of the three key strands of academic activity which it encapsulates: (1) the modelling of criminal action and perpetrator inferences (the focus here is on the differentiation of patterns of criminal action and the determination of the psychological processes underlying these differences that have their origins in individual differences and experiential or lifestyle characteristics of the offender (see Canter and Youngs 2009)), (2) the investigative processes (this includes the study of investigative interviewing techniques as well as the decision-making processes of investigators and juries; although less developed, it extends to considerations of effective legal questioning techniques in court), and (3) the assessment and improvement of investigative information/legal evidence (this includes the study of eyewitness testimony, as well as addressing questions of veracity whether through the study of false allegations, false appeals, false confessions, or forensic psycholinguistic studies of authorship attribution).

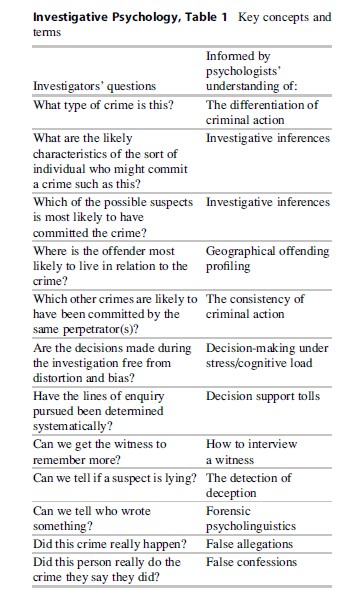

Although the discipline is based upon a distinct philosophical approach to human beings and a particular meta-methodological approach to studying them, the discipline may also be readily understood in terms of the specific and concrete operational questions it seeks to answer (See Table 1: Key Concepts and Terms).

Moving Beyond Offender Profiling To Investigative Psychology

A major emergence of IP was the drawing of outline pictures of offenders, which subsequently became known as “offender profiles.” This activity of giving informed advice to criminal investigations can be traced back to biblical times; this advice grew and developed over the centuries, as illustrated by early description of the characteristics of witches and subsequent proposals of the classification of people on the basis of their physical characteristics and the inferring of criminality from certain subsets of those characteristics. Even though these early attempts at identifying the indicators of deviance were fundamentally flawed, they did point in the direction from which an Investigative Psychology could eventually emerge (see Canter and Youngs 2009). The contributions that IP can make to police investigations are most widely known and typically understood in terms of “offender profiles.” Offender profiling is held to be the process by which individuals, drawing on their clinical or other professional experience, make judgments about the personality traits or psychodynamics of the perpetrators of crimes. Recently, Canter has pointed out that the idea of a distinct “profiling” process is a fallacy.

Certainly, from the perspective of scientific psychology, any such “process” would be flawed in its reliance on clinical judgment rather than actuarial assessment. The clinically derived theories upon which much “offender profiling” has relied are equally questioned by research psychologists (Canter 1995, 2011). Canter modelled the relationship between the offence (A)ctions and offender (C)haracteristics, as canonical equations between particular sets of A and C variables.

The lack of scientific rigor evident in the profiling process has, for two decades, driven proponents of IP research to map out the scientific discipline that could underpin and systematize contributions to investigations. Interestingly, this more academically grounded approach is opening up the potential applications of psychology beyond those areas in which “profiling” first saw the light of day, rather than moving away from operational concerns. Early “profilers” insisted that their skills were only relevant to bizarre crimes in which some form of psychopathology was evident, notably serial killing and serial rape, but investigative psychologists now study and contribute to investigations across the full spectrum of illegal activities.

Nevertheless, as outlined, through the development of a scientific psychological approach to the study of criminal actions and detection processes, a much more challenging set of questions emerge than is apparent in fictional accounts of “profilers.” These require consideration of what is actually consistent for an offender from one situation to another. There is also the challenge of dealing with how a criminal’s actions may change over time due to many different processes of maturation and learning, as well as the variations introduced by any particular situation.

Fundamentals Of Investigative Psychology

The Modelling Of Criminal Action And Perpetrator Inferences

The potential links between the actions associated with a crime and the characteristics of the person who committed that offence are informed by a number of questions that are implicit within the concept of “profiling” and associated activities (Canter 1993; Canter and Youngs 2009).

Salience

In order to generate hypotheses and investigative possibilities and to select from them, detectives and other investigators must draw on some understanding of the actions of the offenders involved in the offence they are investigating. They must have some idea or template of typical ways in which offenders behave that will enable them to make sense of the information obtained. A central research question, then, is to identify the behaviorally important facets of offences – those facets that are of most use in revealing the salient psychological processes inherent in any given crime.

So many different aspects of a crime can be considered when attempting to formulate views about that crime that there is the challenge, before any scientific arguments can be developed, of determining which of those features are behaviorally important, in the sense of carrying information on which reliable empirical findings can be built. Accordingly, determining salience turns out to be a much more complex issue than is often realized with parallels in many areas of information retrieval. It requires the determination of base rates and co-occurrences of behaviors as well as an understanding of the patterns of actions that are typical for any given type of crime.

Consistency

One aspect of these salient features that also needs to be determined as part of scientific development is whether they are consistent enough from one context, or crime, to another, such that they can form the basis for considering and interpreting those crimes and accompany them with other offences. The establishment of consistency is not straightforward. There are weaknesses in the sources of data, particularly “patchiness,” whereby in some instances certain features – or their absence – will be recorded and in others not. To deal with these problems with the data, there is an emerging range of methodologies that focus on working with the sort of information that is available from police and other crime-related sources.

In general, there are two rather different aspects of criminal consistency; one is the consistency from the actions in a crime to other aspects of the offender’s life. This may thus allow some aspects of a one-off crime, such as the expertise involved, to be used to form views about an offender’s previous training. So, the question here is which features of an offence are consistent with which, if any, aspects of an individual’s background and personal characteristics.

A quite distinctly different form of consistency is that between one crime and another committed by the same person. This is often, rather loosely, referred to as an offender’s modus operandi, or M.O. The question here then will be which features of an individual’s offending behavior are consistent across situations, separate offences, and even across different types of offences. There are many aspects of this latter form of consistency that need to be clarified; for the moment we just need to be aware of its relevance at the core of IP.

A more conceptual challenge to determining consistency, as in all human activity, is that some variation and change is a natural aspect of human processes. There therefore will be criminals who are consistently variable or whose behavioral trajectories demonstrate some form of career development, as well as those whose criminal behavior will remain relatively stable over time. Research around all these possibilities of consistency is therefore central to any development of a scientific basis for offender profiling.

Development And Change

Any consideration of consistency will be against a backdrop of likely change in a serial offender’s activities. Some variation is a natural aspect of human processes. Accordingly, there will be criminals who are consistently variable or whose behavioral trajectories demonstrate some form of career development, as well as those whose criminal behavior will remain relatively stable over time. The question of what is characteristic of an offender is one aspect of the operational problem of linking crimes to a common offender in circumstances where there is no forensic evidence to link the case. To date there has been remarkably little research on linking crimes. The challenge to police investigations can be seen as the reverse of the personality question. Psychologists usually have a person and want to know what will be consistent about that person from one situation to another. Police investigators have a variety of situations, criminal events, and need to know what consistencies can be drawn out of those events to point to a common offender.

However, if the basis of these changes can be understood then they can be used to enhance the inference process. The following five relevant forms of change are identified and need to be considered when establishing actions to crime scenes and their relationship to offender characteristics.

Responsiveness. A criminal’s actions may not be the same on two different occasions because of the different circumstances he/she faces. An understanding of these circumstances and how the offender has responded to them may allow some inferences about his/her interpersonal style or situational responsiveness to be made that have implications for the conduct of the investigation.

Maturation. Maturation is an essentially biological process of change in a person’s physiology with age. Knowledge of what is typical of people at certain ages, such as sexual activity or physical agility, can thus be used to estimate the maturity of the person committing the crimes and to explain the possible basis for longer term variations in an individual’s criminal activity.

Development. The unfolding psychological mechanisms that come with age provide a basis for change in cognitive and emotional processes. One reflection of this is an increase in expertise in doing a particular task. Evidence of such expertise in a crime can thus be used to help make inferences about the stages in a criminal’s development that he/ she has reached and indeed to indicate the way their crimes might change in the future.

Learning. Most offenders will learn from their earlier offending in the same way that learning theorists have shown that behavior generally is shaped by experience. So, for example, an offender who struggled to control his first victim may be expected to implement some very definite restraining measures during subsequent offences. Indeed, for offenders, the particularly salient, potentially negative consequences of their actions (e.g., prison) may make this a powerful process for change in the criminal context. An inferential implication of this is that it may be possible to link crimes to a common offender by understanding the logic of how behavior has changed from one offence to the next.

Careers. The most general form of change that may be expected from criminals is one that may be seen as having an analogy to a legitimate career. This would imply stages such as apprenticeship, middle management, leadership, and retirement. Unfortunately, the criminology literature often uses the term “criminal career” simply to mean the sequence of crimes a person has committed. It is also sometimes confused with the idea of a “career criminal,” someone who makes a living entirely out of crime. As a consequence, much less is understood about the utility of the career analogy for criminals than might be expected. There are some indications that the more serious crimes are committed by people who have a history of less serious crimes and that as a consequence, the more serious a crime, the older an offender is likely to be. But a commonly held assumption, such that serious sexual offences are presaged by less serious ones, does not have a lot of empirical evidence in its support.

Cultural Shifts. There are also important changes that come about from the developments in society. Increased security precautions will lead offenders to change their behavior.

Differentiation

Although an offender’s consistency is one of the starting points for empirically based models of investigative inference, in order to use these models operationally, it is also necessary to have some indication of how offenders can be distinguished from each other (Canter 2000). In part, this reflects a debate within criminology about whether offenders are typically specialist or versatile in their patterns of offending. Research suggests that offenders may share many aspects of their criminal styles with most other criminals, but there will be other aspects that are more characteristic of them. It is these rarer, discriminating features that may provide a productive basis for distinguishing between offences and offenders. Canter also posited a conceptual structure known as the Radex (see Canter 2000; Canter and Youngs 2009), as the basis for modelling these patterns of variation and similarity in offending action. As Canter and Youngs (2009) note then, the Radex of Criminal Differentiation hypothesizes that the patterns within criminal action will be organized according to a combination of quantitative and qualitative themes. Numerous empirical studies have supported the Radex hypothesis, leading to recent explorations of the theoretical and conceptual import of this structure.

The rarer features combine to create that which may be regarded as a “style” or “theme” of offending. Therefore, the production of a framework for classifying these different styles is a cornerstone of IP. The classification frameworks are ways of organizing the themes that distinguish crimes which can then be drawn on in inference models so that, rather than being concerned with particular, individual clues as would be typical of detective fiction, the IP approach recognizes that any one criminal action may be unreliably recorded or may not happen because of situational factors. But a group of actions that together indicate some dominant aspects of the offender’s style may be strongly related to some important characteristic.

Recent work has identified a single, generic theoretical framework for understanding the different styles of offending that can be identified across the range of offending forms from burglary or robbery and sexual assault to serial killing or stalking. This is the Narrative Action System model (Canter and Youngs 2009) with its corollary Victim Role Assignments model (Canter 1994; Canter and Youngs 2012). The Narrative Action System identifies four generic styles of offending that reflect the focus and origins of the action (termed an action system mode; see Canter and Youngs 2009) combined with the underpinning criminal narrative : the Hero’s Expressive Quest, the Professional’s Adaptive Adventure, the Revenger’s Conservative Tragedy, and the Victim’s Integrative Irony. The Victim Role model emphasizes the interpersonal components of these generic offending styles, distinguishing the offender’s interpersonal approach to the victim (or “role assignment”) on the basis of different forms of empathy-deficit and control strategies (Canter 1994; Canter and Youngs 2012).

Inferences

As outlined, the heart of these questions is what has become known as the “profiling equations” (Canter 1993, 2011). These are equations that provide the scientific bases for inferring associations between the actions that occur during the offence – including when and where they happen and to whom – and the characteristics of the offender, including the offender’s criminal history, background, base location, and relationships to others. They are also referred to as the “A ! C equations,” where A are the actions related to the crime, and C are the characteristics of typical offenders for such crimes, and ! is the argument and evidence for inferring one from the other.

Although this relationship is not an “equation” in strict mathematical sense, it is helpful to keep the looser meaning implied by the simple formulation. Thinking of the relationships as a family of equations simplifies the discussion of what the central questions of IP are. It also helps to clarify the many challenges and complexities that arise in trying to establish empirically any relationships implied by these equations. It is important to emphasize, though, that specifying the problem as a set of equations does not mean that these are a purely mathematical or statistical way of carrying out profiling. Rather, by studying what would be involved in solving these equations, it becomes clear that we have to use more conceptual, theory-driven approaches if we are to have any hope of producing a scientific basis for psychological contributions to investigations.

A starting point for understanding the challenges inherent in the A ! C relationships is to recognize that the A ! C mapping will rarely take the form of simple one to one relationships, rather there are a range of complexities in the ways that As relate to Cs. These complexities can be thought of as “canonical equations,” which are “the relationships between two sets of variables.” There is always a mixture of criminal actions that are being related to a mixture of characteristics or other criminal actions. The relationships are between combinations of action variables and combinations of characteristic variables. Therefore, the whole concept of a “canonical equation” shows that small changes in any one variable can influence the overall outcome.

Investigative Psychologists have conducted – and continue to conduct – a wide range of empirical studies of different types of crime, with the purpose of establishing solutions to these equations, in the hope of providing objective bases for investigative inferences. The complexity of the A-C relationship does however require the development of theoretical models to explain the relationships that may be expected for different combinations of variables, in different contexts.

Psychological Processes Underlying Investigative Inferences

Once there is some information to work with, there is the significant challenge of determining what conclusions can be drawn from this information. These conclusions are inferences that claim that certain features are linked. The inferences that detectives make in an investigation about the perpetrator’s likely characteristics will be valid to the extent that they are based on appropriate ideas about the processes by which the actions in a crime correlate with the characteristics. Investigative Psychologists have advanced five possible processes that may be drawn upon to develop these inferences: (a) Personality theory, (b) Psychodynamic theory, (c) the career route perspective from criminological theory, (d) social processes, and (e) Interpersonal Narrative theory. Any or all of these theories could provide a valid basis for investigative inferences if the differences in individuals that they possess correspond to real variations in criminal behavior.

One general hypothesis is that offenders will show some consistency between the nature of their crimes and characteristics they exhibit in other situations. This is rather different from psychological models that attempt to explain criminality as a displacement or compensatory activity, resulting from psychological deficiencies. The evidence so far is consistent with this general consistency model, suggesting that processes relating to both the offender’s characteristic interpersonal style and his/her routine activities may be particularly useful in linking actions and characteristics. Valid inferences also depend upon an understanding of the way in which a process operates. Conceptually there are a number of different models that can be drawn on to link an offender’s actions with his/ her characteristics. One is to explain how it is that the offender’s characteristics are the cause of the particular criminal actions. For example, if a man is known to be violent when frustrated, this knowledge provides a basis for inferring his characteristics from his actions. A different theoretical perspective would be to look for variables that were characteristic of the offender and that would influence the particular offending actions. A highly intelligent person, for instance, may be expected to commit a fraud rather differently from someone with educational difficulties. The intelligence may be reflected in the style of action even if not in the actual cause of the action. A third possibility is that actions give rise to some consequences from which characteristics may be inferred. An example of this would be when particular types of goods are stolen that imply that the thief must have contact with other offenders who would buy or distribute those goods.

Other approaches to inference are less based on assumptions about the enduring characteristics of the offender and more on their interpersonal and social context. In terms of “criminal career,” this is the idea that because criminals develop and learn as they commit more and more crimes, their most recent crimes may tell us more about the crimes they have committed in the past than about their enduring characteristics. The need to take on board consistencies in offenders’ characteristics as well as the developments and changes of their lives has been articulated in personal narrative models. This approach also gives more emphasis on the sense the offender makes of his/her life and their agency in acting out their life story as they see it unfolding. This perspective has had particular power in assisting the identification of themes within criminal activities.

From an applied perspective, it is also important that the variables on which the inference models draw are limited to those of utility to police investigations. This implies that the A variables are restricted to those known prior to any suspect being identified, typically crime scene information and/or victim and witness statements. The C variables are limited to those on which the police can act, such as information about where the person might be living, his/her criminal history, age, or domestic circumstances.

These inference models operate at the thematic level, rather than being concerned with particular, individual clues as would be typical of detective fiction. This approach recognizes that any one criminal action may be unreliably recorded or may not happen because of situational factors. But a group of actions that together indicate some dominant aspect of the offender’s style may be strongly related to some important characteristic of the offender.

Investigative Processes: Investigation As Decision-Making

The decision-making phase of the investigative cycle is to select from the various options that are revealed through the earlier stages and act on those options, either to seek further information or to prepare some action that will lead to an arrest or proceedings in court. More specifically, the decision-making tasks that constitute the investigation process can be derived from consideration of the sequence of activities that detectives follow, starting from the point at which a crime is committed through to the bringing of a case to court. As they progress through this sequence of activities, detectives reach choice points, at which they must identify the possibilities for action on the basis of the information they can obtain. For example, when a burglary is committed, they may seek to match fingerprints found at the crime scene with known suspects. This is a relatively straightforward process of making inferences about the likely culprit from the information drawn from the fingerprints. The action of arresting and questioning the suspect follows from this inference.

However, in many cases, the investigative process is not so straightforward. Detectives may not have such clear-cut information, for example, if it is suspected that the style of the burglary is typical of one of a number of people they have arrested in the past. Or, in an even more complex example, they may infer from the disorder at a murder crime scene that the offender was a burglar disturbed in the act. These inferences will either lead them to seek other information or to select from a possible range of actions, including arresting and charging a likely suspect.

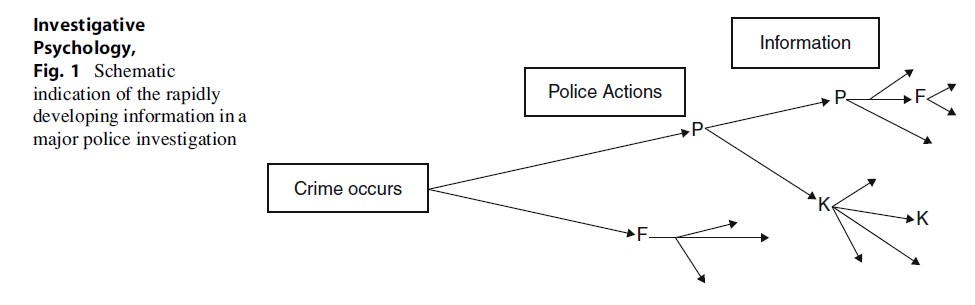

Investigative decision-making thus involves the identification and selection of options, such as possible suspects or lines of enquiry that will lead to the eventual narrowing down of the search process. Throughout this process, detectives must gather the appropriate evidence to identify the perpetrator and prove their case in court. A clear understanding of the investigation process as a series of decision-making tasks allows the challenges implicit in this process to be readily and appropriately identified. The main challenge to investigators is to make important decisions under considerable pressure and in circumstances that are often ambiguous. The events surrounding the decisions are likely to carry a great emotional charge, and there may be other political and organizational stresses that also make objective judgements very difficult. A lot of information, much of which may be of unknown reliability, needs to be amassed and digested. In decision-making terms, the investigative process can be represented as in Fig. 1.

In this diagram the lines represent investigative actions by the police, while the nodes are the results of those actions, i.e., new pieces of information or facts. Immediately after a crime occurs, detectives often have few leads to follow up. However, as they begin to investigate, information comes to light opening up lines of enquiry. These produce more information, suggesting further directions for investigative action. The rapid buildup of information in these first few days will often give rise to exponential increases in the cognitive load on detectives, reaching a maximum weight after some short period of time. At this point, investigators will often be under considerable stress.

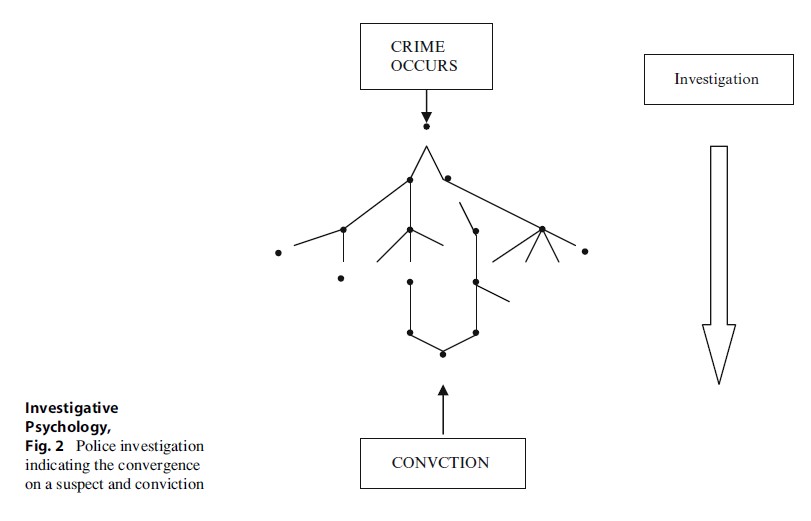

As the investigation progresses, detectives will eventually be able to start to narrow down their lines of enquiry by establishing facts that close off all but one of them, substantially reducing the general level of demand. The general diamond shape in Fig. 2 represents the typical progression of an investigation. The diagram depicts the initial buildup and then the subsequent narrowing down of the information (the nodes) under consideration and investigative steps related to these (the lines) as the investigation becomes increasingly focused to the point where an arrest occurs.

The Assessment And Improvement Of Investigative Information/Legal Evidence

Decisions clearly rely upon information, which is often carved out of real-world events. In a typical police investigation, a mass of information accumulates. The sheer volume of information can reduce the effectiveness of an investigation, as happened in the Yorkshire Ripper enquiry in the UK or more recently in the inquiry into the murder of the English television journalist Jill Dando.

On top of the demands of the amount of information that the police have to deal with is the great variety of material. Each different type of material has to be managed and examined in different ways, requiring different skills and different assessment processes. This information comes from a variety of different sources. There may be photographs or other recordings of the crime scene. There may be records of other transactions such as bills or telephone calls. Increasingly there are records available within computer systems used by witnesses, victims, or suspects. Often there will be witnesses to the crime or results of the crime will be available for examination. Further, there will be information in police and other records that may be drawn upon to provide indications for action. Once suspects are identified, there is further potential information about them, either directly from interviews with them or indirectly through reports from others. In addition, there may be information from various experts that has to be understood and that may lead to specific actions. Apart from being potentially overwhelming in terms of its sheer quantity, the information takes many different forms. It is slanted in many different ways, having been either originally generated for other purposes, or distorted by human perception and memory processes, or, indeed, particular motives. Moreover, while the information available does have certain strengths (such as the fact that it may have been given under oath), it has not been collected with the careful controls of laboratory research. The information on which police rely on in an investigation is therefore often incomplete, ambiguous, and unreliable.

Furthermore, because the information is carved out of real-world events, it must be treated with great respect and considerable caution within IP. A continuum of trustworthiness can be regarded as running from the most trustworthy evidence (the hard evidence at the crime scene) through to the least (the statement of a culprit who denies guilt). The hurdles in the way of trustworthy evidence are present at every stage of an investigation, from initial witness statements, through comments from suspects, to how evidence is presented in court. The challenges this poses for investigations have a different emphasis from those that are posed for research. The biggest problems for research are the biases in the sampling and the gaps and lack of detail in the data. So the researcher always has to work from a record made of the events by some third party.

It is by conceptualizing and treating this information as “data,” and the ways in which it is obtained as research processes, that psychologists can make a further broad class of contribution to investigative activity. Understanding it in this way allows us to use psychological principles and knowledge to evaluate and improve the information detectives need to progress an investigation or to back up a case in court. Two aspects of scientific data assessment are particularly relevant to investigative information: its usefulness and detail and its accuracy and validity.

There are a variety of contributions psychologists can make to the improvement of the accuracy and validity of the information available in an investigation. A number of formal validity assessment techniques have been developed to assess the truthfulness of witness accounts when no objective means of doing this are available. Most of these techniques are based on the assumption that honest accounts have identifiable characteristics that are different from fabricated accounts.

There is much more evidence to indicate that for many people, there are psychophysiological responses that may be indicators of false statements. The procedure for examining these responses is often referred to as a polygraph or “lie detector.” In essence, this procedure records changes in the autonomic arousal system, i.e., emotional response. Such responses occur whenever a person perceives an emotionally significant stimulus. The most well-established indicator is when the respondent is asked to consider information that only the perpetrator would be aware of, known as the “guilty knowledge” test. A more controversial procedure is to ask “control questions” that many people would find emotionally significant, in order to determine if they elicit responses that can be distinguished from those questions relating directly to the crime. However, in both these applications of psychophysiological measures, the most important element is the very careful interview procedure before measurements are made and during the process.

In general “lie detection” is more productive in supporting a claim of innocence than in providing proof of guilt. For this reason, many jurisdictions do not allow “lie detector” results to be presented as evidence in court. Its value in eliminating possible suspects is used in a variety of jurisdictions around the world. In some investigations, the suspect may deny that he/she made a statement that has been attributed to him/her. In such cases, techniques based on the quantitative examination of the language used may be drawn upon to evaluate the claim. So, for instance, a forensic linguist may try to establish whether the use of particular nouns is typical of the suspect or not. Interestingly, however, indications are that the psychological components of written or verbal accounts, i.e., what is meant and how it is expressed, may be more useful in attributing authorship than the linguistic features, such as counts of particular words.

Sometimes the concern will be not with the veracity of the suspect’s account but with that of an alleged victim. This can be an issue in cases of sexual or other abuse. In such cases, the complainant is not a suspect, and the more intrusive processes of lie detection are rarely used. However, investigators can draw on studies of the circumstances under which such false allegations are made and use those as guidelines for more intensive examination of the circumstances. Whether or not this is a valid way of identifying false allegations is a topic awaiting further research.

Investigative Psychology In Action

There has been a long journey from trying to profile the characteristics of a witch through the attempts to fathom the criminal mind of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The experienced detectives, notably at the FBI training academy in Quantico, who drew attention to the possibility of working directly with what occurred in a crime to draw systematic inferences about offenders, pointed the way to a more empirical, scientific basis for psychological and related behavioral science contributions to police investigations. The blossoming of applied psychology into many areas of professional activity laid the foundations for an Investigative Psychology that goes far beyond the initial speculations about serial killers of 50 years ago.

It has been demonstrated throughout this research paper that IP is relevant to the full range of offence activity. Psychology and related disciplines need no longer be assigned to the “hit-and-run” offering of an “offender profile,” which is only relevant to bizarre, extreme crimes. It is now taking its place as of central importance to many aspects of police training and beyond. The groundbreaking work of IP has continuously emphasized the value of systematizing and presenting visualizations of investigative information and the development of decision support systems than can be an integrated aspect of police activities. Two areas in particular are proving fruitful for such decision support: geographical offender profiling and the linking of cases to a common offender. Both of these will benefit from an increasing amalgamation of spatiotemporal and behavioral information as has been attempted in recent investigative decision support systems.

Bibliography:

- Canter D (1993) The wholistic organic researcher: Central issues in clinical research methodology, In: Powell G, Young R & Frosh S (eds) Curriculum in clinical psychology, Leicester: The wholistic organic researcher: Central issues in clinical research methodology. BPS pp 40–56

- Canter D (1994) Criminal Shadows. London: HarperCollins

- Canter DV (1995a) Criminal shadows. HarperCollins, London

- Canter D (1995b) Psychology of offender profiling. In: Bull R, Carson D (eds) Handbook of psychology in legal contests. Wiley, Chichester, pp 343–335, Chapter 4.5

- Canter D (2000) Offender profiling and criminal differentiation. Leg Criminol Psychol 5:23–46

- Canter DV (2003) Mapping murder: the secrets of geographical profiling. Virgin, London

- Canter DV (2011) Resolving the offender “profiling equations” and the emergence of investigative psychology. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 20:5–10

- Canter D (2012) Forensic psychology for dummies. Wiley, New York

- Canter DV, Alison LJ (eds) (1999a) Profiling in policy and practice, networks. Offender profiling series. Aldershot, Dartmouth, pp 157–188, Vol II

- Canter DV, Alison LJ (eds) (1999b) The social psychology of crime: teams, groups, networks. Offender profiling series. Aldershot, Dartmouth, Vol III

- Canter D, Fritzon K (1998) Differentiating arsonists: a model of firesetting actions and characteristics legal and criminal psychology, 3, 73–96

- Canter D, Youngs D (2008a) Principles of geographical offender profiling. Ashgate, Aldershot

- Canter D, Youngs D (2008b) Applications of geographical offender profiling. Ashgate, Aldershot

- Canter D, Youngs D (2009) Investigative psychology: offender profiling and the analysis of criminal action. London: John Wiley & Sons Canter D, Youngs D (in press) Sexual and violent offenders’ role assignments: a generic model of offending style. J Forensic Psychiatr Psychol

- Canter D, Bennell C, Alison L, Reddy S (2003) Differentiating sex offences: a behaviourally based thematic classification of stranger rapes. Behav Sci Law 21:157–174

- Salfati G, Canter D (1999) Differentiating stranger murders: profiling offender characteristics from behavioural styles. Behav Sci Law 17:391–406

- Youngs D (2004) Personality correlates of offence style. J Investig Psychol Offender Profiling 1:99–119

- Youngs D The behavioural analysis of crime: studies in David Canter’s Investigative Psychology (in press). Ashgate, Aldershot

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.