This sample Measurement of Self-Control Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Gottfredson and Hirschi’s concept of self-control is one criminological construct that has sparked a large amount of theoretical and empirical debate among criminologists. The interest in measuring self-control and understanding the psychometric properties of self-control measures is perhaps due to the explanatory power that Gottfredson and Hirschi (1990) attribute to self-control and the theoretical propositions they make regarding this construct. It is therefore surprising that little effort has been made to systematically examine and compile the state of criminological research on the measurement of self-control. This research paper is designed to fill this void by providing a review of several issues related to the measurement of self-control and empirical studies on self-control measurement.

This review will accomplish several tasks. First, conceptual and operational definitions of self-control will be discussed. In doing so, this research paper highlights the disagreements on whether the concept should be operationalized in terms of attitudes and behavior and whether it should be treated as unidimensional or multidimensional. Second, although different measures of self-control have been used by criminologists, this research paper focuses extensively on Grasmick et al.’s 24-item, attitudinal scale, which is arguably the first and most commonly used measure of self-control. Finally, directions for future research are offered that cover a broad range of topics related to the conceptualization and measurement of self-control.

Self-Control Definitions

Gottfredson and Hirschi (1990, p. 89) provide a meticulous account of the six “elements of self-control.” Those lacking self-control will have a “concrete here and now orientation”; “lack diligence, tenacity, or persistence in a course of action”; are “adventuresome, active, and physical, are indifferent, or insensitive to the suffering and needs of others”; and “tend to have minimal tolerance for frustration and little ability to respond to conflict through verbal rather than physical means” (Gottfredson and Hirschi 1990, pp. 89–90). They (Gottfredson and Hirschi 1990, pp. 89–90) link each element of self-control to the criminal act. First, the “here and now” orientation reflects the immediate gratification provided by crime, and those with low self-control have an inclination to respond to tangible stimuli in the immediate environment. Second, lacking diligence, tenacity, or persistence reflects the easy and simple gratification provided by crime, and those with low self-control tend to want immediate rewards without much effort. Third, being adventuresome, active, and physical are reflective of the excitement, risk, and thrill attached to the criminal act. Fourth, being insensitive or indifferent reflects the lack of relevance of the discomfort or pain the victims of criminal acts may experience. Fifth, possessing a marginal tolerance for frustration reflects relief from temporary irritation. These individuals will also possess a volatile temper indicative of their low tolerance for frustration. They note that “there is a considerable tendency for these traits to come together in the same people” (Gottfredson and Hirschi 1990, pp. 90–91).

Some criminologists have interpreted Gottfredson and Hirschi’s definition of selfcontrol as a unidimensional construct because its dimensions should coalesce in a person. According to Trochim (2001, pp. 136), unidimensionality can be thought of as a number line, meaning that one line should be used to reflect higher or lower levels of a trait. For self-control, this would mean that all elements specified by Gottfredson and Hirschi are one and the same and therefore do not represent different attributes as they can all be captured on one number line to indicate more or less self-control.

In one of the first empirical tests of Gottfredson and Hirschi’s theory, Grasmick et al. (1993, pp. 9) explicitly interpreted the concept of self-control as a unidimensional construct:

A factor analysis of valid and reliable indicators of the six components is expected to fit a one factor model, justifying the creation of a single scale called low self-control. In effect, this is a very crucial premise in Gottfredson and Hirschi’s theory. A single, unidimensional personality trait is expected to predict involvement in all varieties of crime as well as academic performance, labor force outcomes, success in marriage, various “imprudent” behaviors such as smoking and drinking, and even the likelihood of being involved in accidents. Evidence that such a trait exists is the most elementary step in a research agenda to test the wealth of hypotheses Gottfredson and Hirschi have presented

Others have also pursued measurement of self-control under a conceptual framework of unidimensionality. For example, Nagin and Paternoster (1993, p. 478) note that “the construct was intended to be unidimensional.” Further, Piquero and Rosay’s (1998, p. 157) interpretation shows consistency with a unidimensional definition when they stated, “evidence for a solution that has more than one factor would not be consistent with Gottfredson and Hirschi’s claim.”

Criminologists have also interpreted Gottfredson and Hirschi’s original conceptualization of self-control as a multidimensional construct, likely due to the elements that embody the concept of self-control. Unlike unidimensionality, it can be problematic to measure a multidimensional construct on a single number line (Trochim 2001, p. 135). For instance, intelligence consists of multiple dimensions such a math and verbal ability. A person may have strong verbal ability and weak math ability. Some argue the same is true for selfcontrol. For example, some individuals may have a high level of impulsivity but also have lower levels of frustration. Various elements of self-control may indicate different, yet correlated, constructs. As such, it would be incorrect to depict a person’s level of self-control using one number line.

While some criminologists suggest that evidence of multidimensionality would be damaging to Gottfredson and Hirschi’s original conceptualization (Longshore et al. 1996), others interpret such evidence as support for their claim (Arneklev et al. 1999; Vazsonyi et al. 2001). Arneklev and colleagues (1999) argued that Gottfredson and Hirschi specify six dimensions of self-control, so the characteristics cannot be anything but multidimensional. What is questionable, according to Arneklev and his colleagues (1999), is whether or not these six elements account for a final, higher-order construct. Vazsonyi et al. (2001) also argued that Gottfredson and Hirschi conclusively outline self-control as a multidimensional trait. However, they also suggest that this is not in contrast to a unidimensional interpretation when they stated that “a multidimensional measure of self-control still can and does imply that these elements together form a single latent trait of self-control” (Vazsonyi et al. 2001, p. 98).

The conceptual confusion resulting from interpretations of Gottfredson and Hirschi’s description of self-control complicates efforts to validate scales designed to specifically test self-control. This is largely because there is no general consensus on how to interpret their construct.

An appropriate operational definition is the second source of controversy regarding self-control as a construct (Akers 1991; Hirschi and Gottfredson 1993, 1994). The controversy surrounds two different operationalizations: attitudinal and behavioral. For Hirschi and Gottfredson (1993), behavior-based operationalizations are preferred. They (Hirschi and Gottfredson 1993, p. 49) explicitly stated, “behavioral measures of self-control seem preferable to self-reports” and “multiple measures [items] are desirable.” In contrast, Akers (1991) has warned against such operationalizations due to a tautology issue of not having indicators of self-control that are independent of outcomes that it should predict. Nevertheless, Hirschi and Gottfredson argue that behavioral indicators can be identified independent of crime. They propose the following:

With respect to crime, we would propose such items as whining, pushing and shoving (as a child); smoking and drinking and excessive television watching and accident frequency (as a teenager); difficulties in interpersonal relations, employment instability, automobile accidents, drinking, and smoking (as an adult). (Hirschi and Gottfredson 1994, p. 9)

Furthermore, Hirschi and Gottfredson (1993) prefer direct behavioral observations when operationalizing self-control, and they put less faith in self-reports. They argue that “the level of self-control itself affects survey responses.. .self-report measures, whether of dependent or independent variables, appear to be less valid the greater the delinquency of those whom they are applied” (Hirschi and Gottfredson 1993, p. 48). While they do not argue for abandoning operational definitions that employ self-report methods to test selfcontrol theory, they do suggest that differences among respondents should be considered in measurement when testing their theory (Hirschi and Gottfredson 1993, p. 48).

Few studies have used direct behavioral observations to measure self-control. For example, Keane and colleagues (1993) used direct observations (i.e., failure to wear a seatbelt) as well as self-report behavioral items (i.e., drinking, perceived risk of being stopped by police) to predict driving under the influence. Most behavioral operationalizations of self-control, however, rely on self-reports. In operationalizing self-control, Zager (1994, p. 75) used an index consisting of “six self-report delinquency items, including alcohol use, marijuana use, making obscene phone calls, avoiding payment, strong arming students, and joyriding.” Similarly, Evans and his colleagues (1997) used an operational definition of low self-control that consisted of self-reports of violating the speed limit, drunk driving, illegal gambling, and using drugs. Many of these self-report behaviors are deviant and criminal acts that Gottfredson and Hirschi (1990) would argue are predicted by low self-control, but they are used in some studies to measure low self-control as well. This can be a problem for researchers when attempting to disentangle cause and effect. Another problem with behavioral measures is the degree of measurement error they contain. For instance, Gibbs and Giever (1995) state that “crime and analogous behaviors as measures of self-control can be expected to contain substantial error because they reflect several underlying variables or constructs” (Gibbs and Giever 1995, p. 249).

The other, probably more favored, operational definition of self-control among criminologists has been attitudinal and/or personality-based self-report items (Grasmick et al. 1993; Gibbs and Giever 1995). Some argue that this method is a way to overcome the tautology problem (Stylianou 2002), while others argue that this approach implies psychological positivism and is incongruent with the self-control construct (Hirschi and Gottfredson 1993).

Gibbs and his colleagues (1998, p. 95) suggest that a variable used to explain behavior “can be most clearly grasped and tested when it is defined as something broader or different than behavior.” An advantage to such an approach is that it “leaves no space for tautology” (Stylianou 2002, p. 538). Additionally, Gibbs and Giever (1995) argue that self-inventory, personality-based operational definitions have advantages over behavioral ones for two reasons: (1.) they are more useful in tapping more cognitive aspects of self-control and (2.) allow for a more comprehensive coverage of domains of self-control because items can be developed to capture typical modes of behavior that relate to everyday life (Gibbs and Giever 1995, p. 249).

Few self-report attitudinal and/or personality-based operational definitions have been developed specifically to test Gottfredson and Hirschi’s construct of self-control (Gibbs and Giever 1995; Grasmick et al. 1993). While Gibbs and Giever (1995) created such a measure, its creation was intended to be relevant only to college students and has not received much empirical attention beyond their own exploratory scrutiny. Grasmick et al. (1993) created a 24-item attitudinal/personality scale based on their interpretation of Gottfredson and Hirschi’s conceptual definition of self-control, and it has been used widely in tests of Gottfredson and Hirschi’s (1990) theory. For instance, Pratt and Cullen (2000) show that at least 12 studies have used Grasmick et al.’s (1993) scale in examining self-control theory, and many others have used it since then (Ward et al. 2010; Gibson et al. 2010). Since Grasmick et al.’s attitudinal scale has been one of the most utilized measures of self-control, the next section provides an extensive review of studies that have been conducted to examine its reliability and validity.

In The Beginning: Creation Of The Grasmick Et Al.’S Self-Control Scale

Grasmick and colleagues paid close attention to how Gottfredson and Hirschi (1990) conceptually defined the elements of self-control and derived an operational definition to reflect its conceptual properties. Grasmick and colleagues (1993) suggested that the six components of self-control can be interpreted as a “personality trait” that should conform to a unidimensional trait.

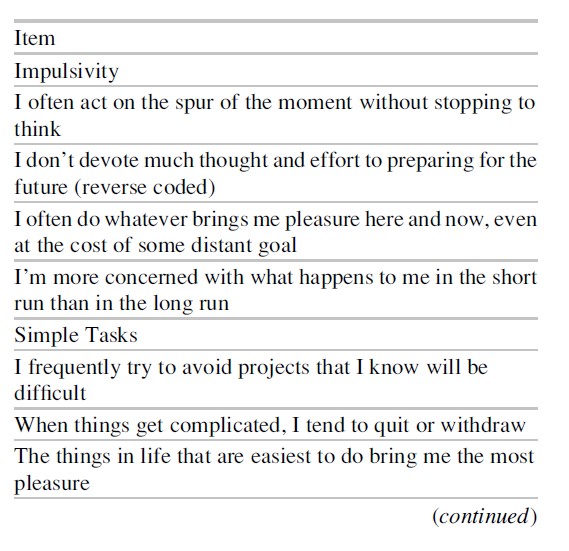

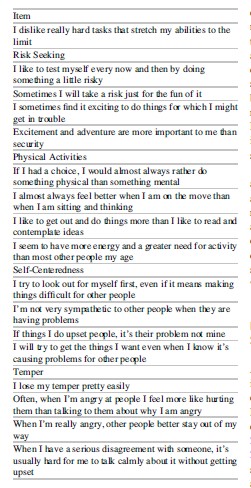

Grasmick and his colleagues used many items in pre-testing college students to identify the final 24 items. This resulted in four items for each of the six elements of self-control. Please see below for lists of the original items. Items were scored on a four-point Likert scale ranging from (1) strongly disagree, (2) disagree somewhat, (3) agree somewhat, and (4) strongly agree.

Grasmick et al.’s (1993) self-control items

While Grasmick and colleagues were quite methodical when determining the face and content validity of the items they used to measure self-control, they neglected other important measurement-related issues. For example, Grasmick and his colleagues (1993) did not give advice on which populations the instrument is appropriate (e.g., college students, juveniles, and incarcerated populations), if directions were explicitly given to respondents, and which scoring procedures should be used for scale construction.

Consequently, it is not clear whether Grasmick et al.’s self-control measure should be equally applied to different samples to discriminate between levels of self-control (or a lack thereof). Perhaps, their scale items are more suitable for low-risk samples, such as college students, rather than high-risk samples, such as serious criminal offenders. The scale items may be too easy or too agreeable for a sample of respondents who, on average, are likely to have lower self-control. This could result in the inability of Grasmick et al.’s scale to accurately measure levels of self-control in some populations.

Although Grasmick and his colleagues (1993) advise readers not to accept their work as a definitive measure of self-control, their scale remains the measuring instrument of choice among researchers attempting to quantify selfcontrol (see Delisi et al. 2003). To support its continued use, however, there must be evidence showing that the scale is empirically reliable and valid and that it is applicable to different samples.

Reliability Of Grasmick Et Al.’S Self-Control Scale

A handful of studies have now explicitly examined the psychometric properties of Grasmick et al.’s self-control scale (Arneklev et al. 1999; Delisi et al. 2003; Gibson et al. 2010; Grasmick et al. 1993; Longshore et al. 1996; Piquero et al. 2000; Piquero and Rosay 1998; Vazsonyi et al. 2001). Most studies employing Grasmick et al.’s scale typically estimate Cronbach’s alpha as a measure of scale reliability. Assuming that the self-control construct is unidimensional, the alpha for this scale should be quite high, or at least modest, ranging from 0.7 to 0.9. Lower internal consistency scores may be a function of the scale’s multidimensionality; however, this would remain an empirical question that reliability estimates alone cannot answer. Although many studies report alpha for the Grasmick et al.’s scale when testing relational propositions of self-control theory, this section specifically summarizes studies that have focused on the psychometric properties of this scale.

Using data from a simple random sample of 395 adult respondents who completed the Oklahoma City Survey, Grasmick and his colleagues (1993) conducted the first reliability analysis of their scale. They concluded that by dropping one item (the last item under the Physical Activities component) from the scale, they could increase reliability from 0.80 to 0.81.

Two studies using the same data set emerged in 1996 and 1998, which came from a multisite evaluation of Treatment Alternatives to Street Crime (TASC) programs to identify drug-using adult and juvenile offenders in the criminal justice system to gauge their treatment needs. The sample consisted of 623 offenders. Most sample respondents had lengthy criminal histories, and the sample varied in sex, race, and age. It should be noted that the version of the scale in these studies diverges slightly from its original form in a few ways. First, Longshore et al. (1996) modified the original response scale and added an additional category to make it a five-point Likert scale: never (0), rarely (1), sometimes (2), often (3), and almost always (4). Second, item wording was changed and often reversed to detect any bias from yes-saying. Longshore et al. (1996) reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.80 for the Grasmick et al.’s scale, whereas Piquero and Rosay (1998) reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.71. Piquero and Rosay (1998) reported genderspecific alpha’s, 0.72 for males and 0.68 for females.

Both Longshore et al. (1996) and Piquero and Rosay (1998) reported reliability estimates for each self-control dimension, which were low compared to acceptable standards. Longshore et al.’s (1996) estimates were 0.65 for Impulsivity/Self-Centeredness, 0.48 for Simple Tasks, 0.58 for Risk Seeking, 0.35 for Physical Activities, and 0.71 for Temper. Piquero and Rosay’s (1998) estimates were 0.45 for Impulsivity (0.46 for males and 0.43 for females), 0.44 for Simple Tasks (0.47 for males and 0.28 for females), 0.58 for Risk Seeking (0.58 for males and 0.56 for females), 0.37 for Physical Activities (0.40 for males and 0.31 for females), 0.68 for Temper (0.71 for males and 0.59 for females), and 0.57 for Self-Centeredness (0.59 for males and 0.49 for females). The difference was that Longshore et al. (1996) reported alpha’s on only five of the six components; they combined Impulsivity and Self-Centeredness items due to the results of their factor analysis that is discussed in the next section.

Delisi et al. (2003) used data collected from 208 male parolees residing in work release facilities in a midwestern state that had been previously released from prison. They reported that Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale was 0.91. They also computed reliability estimates for each component showing coefficients of 0.79 for Impulsivity, 0.81 for Simple Tasks, 0.79 for Risk Seeking, 0.72 for Physical Tasks, 0.81 for Self-Centeredness, and 0.86 for Temper.

In the largest study undertaken to investigate the psychometric properties of Grasmick et al.’s scale, Vazsonyi et al. (2001) gathered data on over 8,000 adolescents from four different countries including schools in Hungary (n = 871), Netherlands (n =1,315), Switzerland (n = 4,018), and the United States (2,213). While total scale reliability estimates are not reported, they do report them for self-control sub- scales for the total and country-specific samples. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.50 for Impulsivity ranging from 0.45 to 0.62; 0.68 for Simple Tasks ranging from 0.61 to 0.73; 0.79 for Risk Seeking ranging from 0.69 to 0.84; 0.63 for Physical Activities ranging from 0.55 to 0.74; 0.60 for Self-Centeredness ranging from 0.45 to 0.68; and 0.76 for Temper ranging from 0.68 to 0.76.

Gibson and colleagues (2010) analyzed a sample of 333 college students attending a university in the southern United States. They reported alpha coefficients for the full 24-item self-control measure and each of the six components for males and females separately. They found that the 24-item self-control measure had an alpha coefficient of 0.84 for males and 0.85 for females. Their assessment of the reliability of each dimension found an alpha coefficient for Impulsivity of 0.65 and 0.69 for males and females, respectively; for Simple Tasks was 0.75 and 0.77 for males and females, respectively; Risk Taking was 0.78 and 0.75 for males and females, respectively; Physical Activities was 0.81 and 0.80 for males and females, respectively; Self-Centeredness was 0.77 and 0.65 for males and females, respectively; and for Temper the estimates were 0.79 and 0.76 for males and females, respectively.

Dimensionality Of Grasmick Et Al.’S Scale

Grasmick et al. (1993) were the first to assess the dimensionality of their scale. First, they performed a principal components exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with one-, five-, and sixfactor solutions. They could not “find strong evidence that combinations of items into subgroups produces readily interpretable multidimensionality” (Grasmick et al. 1993, p. 17). Their analysis led them to conclude that “the strongest case can be made for a one-factor unidimensional model” (Grasmick et al. 1993, p. 17). Several studies have since shown similar results using the same method across different samples (Arneklev et al. 1999; Nagin and Paternoster 1993; Piquero and Tibbetts 1996; Piquero et al. 2000; Delisi et al. 2003), concluding that all items load moderately on the first factor which is interpreted as evidence of unidimensionality. However, these exploratory analyses also provided evidence for six factors. As such, the methods used in these studies were not ideal for concluding whether Grasmick et al.’s scale is unidimensional or multidimensional.

Depending on researchers’ perceptions of the original conceptualization of self-control, findings from these studies have been interpreted as having multiple factors or one factor. Furthermore, EFA, e.g., principal components analysis, reduce multiple variables (or items) without an imposed theoretical structure, and they attempt to extract the most variance possible from the initial factor. EFA leaves the task of defining the number of factors up to the factor analysis program, therefore being inadequate for construct validity purposes (DeVellis 1991).

Some criminologists have used confirmatory measurement models that are more appropriate for construct validation. Results from these models have often led to divergent conclusions compared to Grasmick et al.’s (1993) original analysis. For instance, Longshore et al. (1996) and Piquero and Rosay (1998) used the same data from a sample of drug-using offenders and found that the Grasmick et al.’s scale items fit two different models, a unidimensional solution and a multidimensional solution with slight modifications to the scale items, e.g., dropping items from the analysis.

Longshore et al. (1996) did not find initial support for a single underlying factor, and the scale did not appear to function equally well across subgroups defined by race, sex, and age. They modified the scale by dropping two items and allowing several error terms to correlate in a confirmatory measurement model, still concluding that a one-factor solution did not adequately fit the data. Next, they assessed a five-factor solution by combining two of the components, i.e., Impulsivity and Self-Centeredness. This solution also provided a poor fit to the data until they allowed four error terms to correlate and one item to load on two different factors. Their modified five-factor solution provided a better fit to the data especially for juveniles (CFI=0.89), males (CFI=0.92), Caucasians (CFI=93), African-Americans (CFI=0.92), and adults (CFI=0.91). This solution, however, provided a poor fit for women (CFI=0.80). Most importantly, their results questioned the unidimensionality of the scale for a criminal population.

Piquero and Rosay (1998) reanalyzed the data used by Longshore and colleagues. They argued that the scale could conform to a one-factor solution, could be equally reliable and valid across gender, and could produce a good fit to the data without allowing error terms to correlate. Their confirmatory measurement model showed that a unidimensional model fit the data for both males and females, but they did drop several items from the scale reducing it to 19 items. For example, the Physical Activities component was reduced to two items, and the Impulsivity, Simple Tasks, and Self-Centeredness components were all reduced to three items.

Although Piquero and Rosay (1998) are confident that their results garnered supported for unidimensionality, others disagree and conclude that their results are analogous to a second-order factor analysis where one overarching factor accounts for the relationships among lower-level factors (Longshore et al. 1996). This criticism is based on Piquero and Rosay’s (1998) averaging of the scores within each component or dimension and their use of the final six composite scores as indicators in a one-factor measurement model. In sum, the results produced by these two studies do not provide a clear, unambiguous understanding of the internal validity of self-control. In both cases, modifications were made to the scale so that the results from the analyses could conform to either a multidimensional or unidimensional measure.

Arneklev et al. (1999) employed a secondorder, confirmatory measurement model to test the dimensionality of Grasmick et al.’s scale. In doing so, they argued that a valid measure of self-control should have six distinct dimensions that load on a higher-order self-control factor. Using a random sample of adults and a convenience sample of college students, they concluded that a second-order model fits the data well. For the adult sample, the results showed that the coefficients between both the indicators and the six dimensions of self-control and the six dimensions and the self-control latent construct were sufficiently large. Although each of the six dimensions was significantly related to the second-order self-control factor, they found that Impulsivity had the highest factor loading. Additionally, the Physical Activities dimension loaded less strongly on self-control than any other dimension. Overall, Arneklev and his colleagues (1999) concluded that the second-order factor model for the adult sample provided support for Gottfredson and Hirschi’s (1993) theory; the goodness of fit statistic (GFI ¼ 0.89) had an acceptable magnitude, indicating that the proposed theoretical model fit the data well. Arneklev et al. (1999) showed similar results for their college sample. Arneklev et al. (1999) concluded that evidence of six distinct dimensions exists, but evidence also indicated that all six dimensions loaded on a higher-order construct that they called self-control.

Vazsonyi and his colleagues (2001) used both exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis in their study of Grasmick et al.’s self-control scale for adolescents across four countries. In an a priori fashion, they interpreted Gottfredson and Hirschi’s (1990) conceptualization of self-control to be multidimensional, consisting of six separate dimensions. They first estimated exploratory factor analysis models for the total sample as well as for groups by sex, age, and country. Vazsonyi et al. (2001) argued that their preliminary results indicated the existence of six factors and that the scale is not unidimensional. Second, they use all 24 items to conduct a series of more rigorous confirmatory models including a one-factor and six-factor model to confirm their exploratory efforts. Using several fit statistics (e.g., CFI=0.65, GFI =0.82, and RMSEA=0.09 for the total sample), they concluded that a one-factor model was not a good fit to their data. Each item, however, did show a statistically significant loading. In contrast, they showed that a six-factor solution fits the data much better (e.g., CFI=0.91, GFI =0.95, and RMSEA= 0.05 for the total sample), even across groups by age, sex, and country. In a final attempt to improve the six-order factor model, they allowed for two correlated error terms and dropped two items from the scale to achieve a consistent, overall, improved fit (e.g., CFI = 0.93, GFI =0.96, and RMSEA =0.04 for the total sample) which did not vary much across groups. Unlike others (Arneklev et al. 1999; Delisi et al. 2003; Piquero et al. 2000), Vazsonyi and his colleagues did not test a secondorder factor model.

Delisi et al. (2003) tested the dimensionality of Grasmick et al.’s scale using a sample of male offenders residing in work release facilities in a midwestern state. They employed confirmatory measurement models to test one-factor, six-factor, and second-order factor models. While all loadings were statistically significant in all models, they concluded that all models fit the data poorly. These conclusions were drawn using numerous fit statistics. Most troubling for the unidimensionality hypothesis was their finding showing that the one-factor solution had the worst fit among the confirmatory factor models (GFI =0.65, AGFI=0.59, RMR =0.11, and x2/df=4.27). From Delisi et al.’s (2003) confirmatory analyses, a model building effort was undertaken. They found that a modified six-factor model was able to fit their data well.

In sum, the evidence for the dimensionality of the most commonly used measure of self-control turns out to be inconclusive. While researchers continue to use it as if it is measuring one construct, evidence suggests that this may not be the case. This can have implications for the impact of self-control on outcomes hypothesized by Gottfredson and Hirschi. For instance, if Grasmick et al.’s self-control measure is actually multidimensional, then not treating it as such may mask the importance of each dimension’s influence on criminal behavior, substance use, and other antisocial behaviors. Specifically, some dimensions may be relatively more important than others in predicting particular behavioral outcomes, or some dimensions may even interact with one another in important ways. By treating this measure as unidimensional, these possibilities will not be realized. Some criminologists have actually found that not every dimension of the scale is important in explaining criminal outcomes (Delisi et al. 2003). Others have found particular dimensions of Grasmick et al.’s scale, e.g., Impulsivity and Risk Seeking, to be more important than the overall self-control scale when predicting criminal outcomes (Longshore et al. 1996).

The Rasch Measurement Model And Self-Control

Piquero and his colleagues (2000) were the first to apply a Rasch measurement model to investigate the internal validity of Grasmick et al.’s selfcontrol scale. The Rasch model is a confirmatory measurement model that tests for scale unidimensionality, but it diverges from traditional confirmatory measurement models discussed thus far in several important ways. First, the Rasch model produces distributionfree estimates in that the values do not depend on the distribution of the trait, i.e., self-control, across samples as do conventional exploratory and confirmatory factor models. This is important because results from Rasch models can be compared across samples when the same scale is employed, while results from factor analysis models are questionable for comparative purposes (Piquero et al. 2000; Bond and Fox 2001).

Second, a Rasch model separates person ability and item difficulty estimates and then places them both on the same logit ruler for comparative purposes. This function allows for comparisons of item difficulty in relation to people’s level of ability, i.e., self-control, on the same intervallevel scale. By taking into account the interaction between persons and scale items, the Rasch model overcomes the test-based approach of conventional confirmatory factor analysis. As such, the ability estimates do not depend on the difficulty of items in the scale. A Rasch model allows a researcher to detect the difficulty of endorsing items in relation to the distribution of self-control in the sample.

Third, the Rasch model is mathematically defined to assess unidimensionality. In doing so, each self-control scale item is examined to assess its fit to the model. Finally, Rasch models create interval-level measures from ordinal items, whereas factor analysis methods in several statistical software packages mistake ordinal responses for continuous responses violating statistical assumptions (see Piquero et al. 2000; Wright and Masters 1982).

Piquero et al. (2000) were interested in whether respondents used item response categories as they were supposed to. The use of response categories was orderly; those with low levels of self-control had higher probabilities of agreeing to low self-control items (selecting response categories that reflect low self-control) than those with high self-control. Second, they were interested in how well scale items fit the unidimensional Rasch model. They found that many items had poor fit to the unidimensional expectation of the model. Particularly, they found that 11 of the 24 items showed statistically significant misfit when all items were considered as a unidimensional measure. Third, Piquero et al. (2000) investigated a person/item logit ruler generated by Rasch modeling software to determine that several items were too difficult for their college sample to endorse. A logit ruler, or person/item map, allows researchers to assess the distributions of ability and item difficulty on the same metric (i.e., logit scale) to determine if items are too difficult to endorse relative to the distribution of the sample’s self-control. Most of their sample had very low ability indicating high levels of self-control. The Grasmick et al.’s items did not discriminate well among a college sample with disproportionately high levels of self-control. Finally, Piquero et al. (2000) conducted a differential item function (DIF) analysis to assess item responses across high and low self-control groups. Low-self-control individuals were found in some instances to respond to items differently than those having high self-control. Particularly, the low selfcontrol group was more (or less) willing to agree with some items than would have been expected by the Rasch model.

In a more recent study, Gibson et al. (2010) used a Rasch Model to assess how Grasmick et al.’s self-control items may perform differently for a sample of male and female college students. Gibson and colleagues’ investigation found that self-control items performed differently for men and women. In fact, 33 % of the items showed differential item function. In some cases, women were less likely to agree to items compared to men even when males and females had similar levels of the trait. This means that several of the items were biased for men and women and that this could inflate or deflate aggregate self-control differences between them. When the biased items were excluded from the scale, a gender difference in aggregate self-control was still observed, but the difference was reduced.

In sum, the few studies that have used a Rasch model to investigate the internal validity of Grasmick et al.’s self-control measure have found that the items do not conform to a unidimensional trait and potential biases exist for using it to measure self-control for different groups. While this is a relatively new approach to investigating the validity of self-control measures, researchers should continue to use it in the future for several reasons. First, the differential item functioning capabilities of the Rasch model will be helpful for understanding if self-control measures can or should be applied to different groups including gender, race, community samples, adolescents, and prison samples to name only a few. Second, and from a developmental perspective, this approach will allow researchers to determine if measures of self-control such as the Grasmick et al.’s scale items will have similar or different meanings as people age. As such, this will allow a researcher to determine if true change in this construct is occurring within individuals over time or if differences observed within individuals over time are due to the items having different meanings for individuals as they age. Third, the Rasch model has the valuable property of being able to determine if self-control items are able to discriminate well between individuals with low to high levels of self-control.

Conclusions And Future Research

This research paper has provided a review of key issues related to the measurement of self-control. Of these, several noteworthy themes emerged. First, much less criminological research has focused on the measurement of self-control compared to the large body of work that has investigated the influence of self-control on a variety of behavioral outcomes. This is unfortunate because the research on self-control measurement has produced little agreement among criminologists as to what measure should be used to capture this important construct.

Second, further complicating the disagreement among criminologists is the conceptual and operational definitions provided by Gottfredson and Hirschi. Although they were creative in linking elements of self-control directly to the criminal act, they leave readers questioning whether self-control should be interpreted as a unidimensional or multidimensional construct and the merits of behavioral measures. These issues have implications for how criminologists should proceed in testing the influence of self-control on behavioral outcomes; that is, should researchers examine the effect of each of self-control’s dimensions on outcomes or the combined effect of self-control or both? Moreover, recent studies that attempt to expand self-control theory have used quite different and diverse measures of self-control. It is likely that some measures being used are more valid and reliable than others, but this must be acknowledged and empirically addressed before determining the true effects of self-control on behavioral outcomes or the casual underpinnings of self-control.

Third, it was noted that one of the most common measures used by criminologists to assess differences in self-control among individuals has been Grasmick et al.’s scale or a reduced version of it. The empirical studies conducted to date on the psychometric properties of this measure are mixed. Studies estimating the reliability of Grasmick et al.’s scale have employed diverse samples ranging from convicted offenders, adult community members, adolescents residing in different countries, and college students. Only one of these studies reports a Cronbach’s alpha above 0.9 for the total scale (Delisi et al. 2003); however, other studies do indicate that the scale has modest to high reliability. This is necessary, but not sufficient, for demonstrating scale validity. The scale items appear to cohere more closely in some samples than others, and some studies show low reliability for subscales. In addition, Grasmick et al. (1993) explicitly stated that a factor analysis of valid and reliable indicators of self-control should produce a unidimensional measure and they found support for their hypothesis, but they used an exploratory analytic method to make such an inference. Since then, several rigorous examinations of the scale have refuted their claims. In contrast, the scale has often been shown to be multidimensional reflecting either six-factor or a second-order factor structure where dimensions load on a latent self-control factor with some dimensions loading more strongly than others. As such, more studies in the future should investigate closely how each of these dimensions differentially influence outcomes that Gottfredson and Hirschi would predict are affected by self-control.

Fourth, conflicting results have emerged as to the Grasmick et al.’s scale’s dimensionality and validity across demographic groups using traditional confirmatory measurement models and the Rasch model. For example, conflicting results have been found for whether the scale is equally reliable and valid for blacks, Hispanics, whites, males, and females. Gottfredson and Hirschi (1990) do not clearly specify the factor structure that a valid measure of self-control should posses, let alone how such a structure would hold up across different races. The Rasch model holds promise for understanding if the Grasmick et al.’s scale and other measures of self-control are unbiased across different groups.

Since the 1990s, few studies have been published in criminology that primarily center on the measurement of self-control. With some exceptions, most studies that have done so focus on the dimensionality debate of Grasmick et al.’s self-control scale using a variety of samples. As such, research on the measurement of self-control is open to new ideas and can hold much promise for criminology. A set of ideas for those pursuing research on the measurement of self-control is discussed below.

First, compiling a systematic list of all self-control measures used in past criminological research would be beneficial for researchers interested in exploring self-control theory. As such, criminologists would be able to assess the positive and negative attributes of each and make decisions on which measures or measure best fits their purpose.

Second, different conceptual and operational definitions should be pursued by criminologists, especially given Gottfredson and Hirschi’s disapproval of the Grasmick et al.’s scale and Hirschi’s more recent re-conceptualization of the self-control concept which suggests that self-control and social control are the same (Hirschi 2004). A recent effort has been made by Marcus (2004). Opposed to the idea that six elements define the construct of self-control, Marcus (2004) argued that Gottfredson and Hirschi’s (1994, p. 3) construct is simply “the tendency to avoid acts whose long-term costs exceed their monetary advantages.” Marcus acknowledges that Grasmick et al.’s 24 items reflect six traits and these traits overlap with a large body of literature on the structure of personality. He argued that elements such as risk seeking and preference for easy tasks measured by this instrument reflect a motivational basis of behavioral choice and do not reflect behavioral constraint. Given this conceptual flaw, he argued that Grasmick et al.’s measure is incompatible with the main premise of self-control theory. In fact, he argued that the six elements measured by Grasmick et al.’s scale are linked to the five-factor model (FFM) of personality. So, if Grasmick et al.’s scale is a unique measure of Gottfredson and Hirschi’s construct of self-control and not merely a measure that is tapping into several personality traits, then it should show divergent validity when compared to a widely used and psychometrically sound instrument of the FFM. Future research should explore this idea by empirically investigating the correlations between Grasmick et al.’s subscales and the most well-researched instrument used to measure the FFM of personality, the NEO personality inventory.

Third, given Gottfredson and Hirschi’s preference for behavioral self-control measures, an important line of future research on the measurement of self-control will be to create behavioral measures and empirically compare them to Grasmick et al.’s measure to assess divergent and convergent validity. Although such investigations have received limited empirical attention (Tittle et al. 2003), very few attempts have been made to create a behavioral measure that is consistent with Gottfredson and Hirschi’s conceptual definition of self-control. Marcus (2004) has created a self-control measure that consists of 67 strictly behavioral statements that are designed to assess the frequency of prior conduct across developmental stage that have long-term negative consequences. Future research should not only investigate how Marcus’s scale correlates with Grasmick et al.’s measure but should assess the predictive validity of his measure and compare it to the predictive validity of Grasmick et al.’s measure (see Ward et al. 2010).

Fourth, researchers should further explore the validity of self-control measures for different types of people, especially given the possibility that one’s own self-control can affect his/her survey responses. Responses may be less valid for individuals with higher criminality and/or lower self-control (Hirschi and Gottfredson 1993; Piquero et al. 2000). With regard to the measurement of self-control, this is a topic that has received minimal empirical attention. Hirschi and Gottfredson (1993) have argued that a solution would be to collect behavioral indicators of self-control that are measured independent of respondents; for instance, having parents or teachers report on the behaviors of children and adolescents (see also Gibson et al. 2010). Acknowledging that such a solution could be a financial burden to researchers that do not have funds to collect direct observational data, an alternative to Hirschi and Gottfredson’s solution would be to employ methods that would enhance the accuracy of survey responses from those having lower levels of self-control. In doing so, researchers could consider the nature of self-control and how it may guide item creation and scale formatting.

The research ideas discussed here should be seen as ways for improving self-control measures used by criminologists, but they should not be the only measurement endeavors pursued. If the concept of self-control is as important for understanding criminal and antisocial outcomes as criminologists suggest, it will be even more important to refine measures of self-control in ways that most accurately reflect the conceptual and operational definition of the construct. At the same time it is important for criminologists to move toward the creation of a psychometrically reliable and valid measure that will be used to capture differences in self-control for populations of interest to criminologists.

Bibliography:

- Akers RJ (1991) Self-control as a general theory of crime. J Quant Criminol 7:201–211

- Arneklev BJ, Grasmick HG, Bursik RJ Jr, (1999) Evaluating the dimensionality and invariance of “low self-control.” J Quant Criminol 15:307–331

- Bentler PM (1990) Comparative fit indexes in structural equation models. Psychol Bull 107:238–246

- Bond TG, Fox CM (2001) Applying the Rasch model: fundamental measurement in the human sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah

- Delisi M, Hochstetler A, Murphy DS (2003) Self-control behind bars: a validation study of the Grasmick et al. scale. J Quarterly 20:241–263

- DeVellis RF (1991) Scale development. Sage, Newbury Park

- Evans TD, Cullen FT, Burton VE Jr, Dunaway RG, Benson ML (1997) The social consequences of self-control theory. Criminology 35(3):475–501

- Gibbs JJ, Giever D (1995) Self-control and its manifestations among university students: an empirical test of Gottfredson and Hirschi’s general theory. JQ 12:231–255

- Gibbs JJ, Giever D, Martin JS (1998) Parental management and self-control: an empirical test of Gottfredson and Hirschi’s general theory. J Res Crime Delinq 35:40–70

- Gibson CL, Sullivan C, Jones S, Piquero A (2010a) Does it take a assessing neighborhood effects on self-control. J Res Crime Delinq 47:31–62

- Gibson CL, Ward JT, Wright JP, Beaver KM, DeLisi M (2010b) Where does gender fit in the measurement of self-control. Criminal Justice Behav 36:883–903

- Gottfredson MR, Hirschi T (1990) A general theory of crime. Stanford University Press, Stanford

- Grasmick HG, Tittle CR, Bursik RJ, Arneklev BJ (1993) Testing the core empirical implications of Gottfredson and Hirschi’s general theory of crime. J Res Crime Delinq 30:5–29

- Hambleton RK, Swaminathan H, Jane Rogers H (1991) Fundamentals of item response theory. Sage, Newbury Park

- Hirschi T (2004) Self-control and crime. In: Baumiester RF, Vohs KD (eds) Handbook on self-regulation: research, theory, and application. Guilford, New York, pp 53–552

- Hirschi T, Gottfredson MR (1993) Commentary: testing the general theory of crime. J Res Crime Delinq 30:47–54

- Hirschi T, Gottfredson MR (1994) The generality of deviance. In: Hirschi T, Gottfredson MR (eds) The generality of deviance. Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick

- Keane C, Maxim PS, Teevan JJ (1993) Drinking and driving, self-control, and gender: testing the general theory of crime. J Res Crime and Delinq 30:30–46

- Longshore D, Turner S, Stein JA (1996) Self-control in a criminal sample: an examination of construct validity. Criminology 34:209–228

- Marcus B (2004) Self-control in the general theory of crime: theoretical implications of a measurement problem. Theor Criminol 8:33–35

- Nagin DS, Paternoster R (1993) Enduring individual differences and rational choice theories of crime. Law and Soc Rev 27:467–496

- Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH (1994) Psychometric theory, 3rd edn. McGraw Hill, New York

- Paternoster R, Brame R (1998) The structural similarity of processes generating criminal and analogous behavior. Criminology 36:633–670

- Piquero AR, Tibbetts S (1996) Specifying the direct and indirect effects of low self–control and situational factors in offender’s decision making. Justice Quart 13:481–510

- Piquero AR, Rosay AB (1998) The reliability and validity of Grasmick et al.’s self-control scale: a comment on Longshore et al. Criminology 36:157–173

- Piquero AR, MacIntosh R, Hickman M (2000) Does self-control affect survey response? Applying exploratory, confirmatory, and item response theory analysis to Grasmick et al.’s self-control scale. Criminology 38:897–929

- Pratt TC, Cullen FT (2000) The empirical status of Gottfredson and Hirschi’s general theory of crime: A meta–analysis. Criminology 38:931–964

- Stylianou S (2002) Relationship between element and manifestations of low self-control in a general theory of crime: two comments and a test. Deviant Behav 23:531–557

- Tittle CR, Ward DA, Grasmick HG (2003) Self-control and crime/deviance: cognitive vs. behavioral measures. J Quantitative Criminol 19:333–365

- Trochim WMK (2001) The research methods knowledge base. Atomic Dog Publishing, Cincinnati

- Vazsonyi AT, Pickering LE, Junger M, Hessing D (2001) An empirical test of a general theory of crime: a fournation comparative study of self-control and the prediction of deviance. J Res Crime Delinq 38:91–131

- Ward JT, Gibson CL, Boman J, Leite WL (2010) Is the general theory of crime really stronger than the evidence suggests? Assessing the validity of the retrospective behavioral self-control scale. Criminal Justice Behav 37:336–357

- Wright BD, Masters GN (1982) Rating scale analysis. MESA Press, Chicago

- Zager MA (1994) Gender and crime. In: Hirschi T, Gottfredson MR (eds) The generality of deviance. Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.