This sample Overview Assessment and Evaluation Research Paperis published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Outline

- Introduction

- Theoretical Perspectives

- Methods and Techniques

- The Process of Assessment, Treatment, and Evaluation

- Conclusions

1. Introduction

1.1. Concept

Psychological assessment is the discipline of scientific psychology devoted to the study of a given human subject (or group of subjects) in a scientific applied field— clinical, educational, work, etc., by means of scientific tools (tests and other measurement instruments), with

the purpose of answering client’s demands that require scientific operations such as describing, diagnosing, predicting, explaining or changing the behavior of that subject. —Ferna´ndez-Ballesteros et al., 2001.

Throughout the history of applied psychology, psychological assessment has been a key discipline, often to the extent of being confused with psychology itself and of constituting the public face of psychology. As several empirical studies have pointed out, assessment tasks are an ever-present element in all psychological work, from the scientific laboratory to applied settings. Thus, all types of psychological work involve assessment at some stage and to some extent, whether it be through the use of sophisticated data collection equipment, structured interviews, or qualitative observations, or by means of complex measures obtained through the administration of tests.

1.2. Brief History

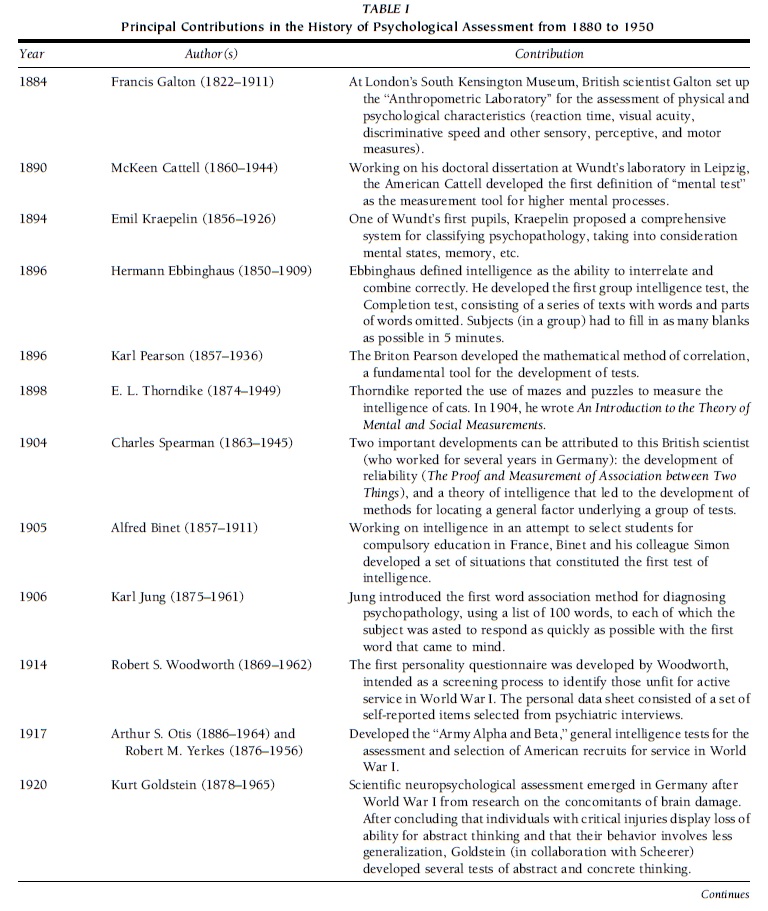

Psychological assessment in some form or another can be found throughout the history of human thinking, in the Bible, in ancient China, and even in the works of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle or those of the ancient physicians Hippocrates and Galen. Nevertheless, it is not until the late 19th century that we find scientific events related to psychological assessment. Table I offers an overview of the most important contributions to psychological assessment from the starting point of scientific psychology—the founding of Wundt’s Psychology Laboratory in Leipzig in 1878—until 1950. As can be seen in Table I, psychological assessment is a sub-discipline developed at the same time as experimental psychology. While psychology is devoted to the study of the principles of mind, consciousness, and behavior, psychological assessment is devoted to the study of how, or to what extent, these principles are fulfilled in a specific subject or group of subjects. For the study of a particular subject (or group of subjects), psychological assessment requires methods for data collection. Thus, psychological assessment is closely related to psychometrics and to psychological testing. Methodological advances in psychometric theory are important because all measurement devices are developed and evaluated using psychometric criteria; psychological testing and psychological assessment have even been confused. But psychological assessment cannot be reduced to either psychometrics or the processes of administering tests. Rather, as referred to in the above definition, psychological assessment always involves a process of problem-solving and decision-making in which measurement devices and other procedures for collecting data are administered for testing hypotheses about a subject (or group of subjects), with the specific purpose of answering relevant questions asked by the client or the subject. The client and subject may be the same person or unit, or the client may be another professional or relative (e.g., a psychiatrist, an educator or a judge) who asks for the assessment of a third person or group of persons with a given purpose (description, classification, diagnosis, prediction, prognosis, selection, change, treatment, or evaluation).

1.3. Objectives and Contexts

But these applied questions require scientific objectives, of which the following are the most common: description, classification, prediction, explanation, control, and evaluation. By way of example: when a psychiatrist asks a psychologist for a diagnosis of a given patient, the psychologist should proceed to the description and classification of the patient; when a client asks a psychologist who is the best candidate for a job, the psychologist must predict the candidate who is likely to perform best; when a couple or a family asks for counseling, the psychologist should analyze the situation before intervening; when a pupil has a learning problem, the psychologist must analyze the case and hypothesize about the circumstances that explain or cause the problem, manipulate its cause(s), and evaluate the extent to which it has been solved.

As can be seen from the examples, these various objectives emerge from different applied settings, the three most common assessment contexts being clinical psychology, educational psychology, and work and industrial psychology.

Finally, the relevant events listed in Table I emerge from different models of scientific psychology, are related to specific psychological content or targets (intelligence, aptitudes, personality characteristics, etc.), and imply a variety of methods (interview, self-reports, projective techniques, etc.).

2. Theoretical Perspectives

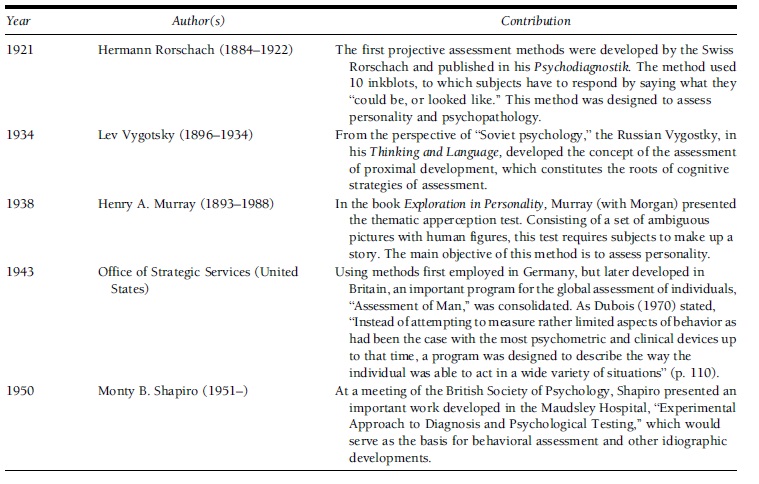

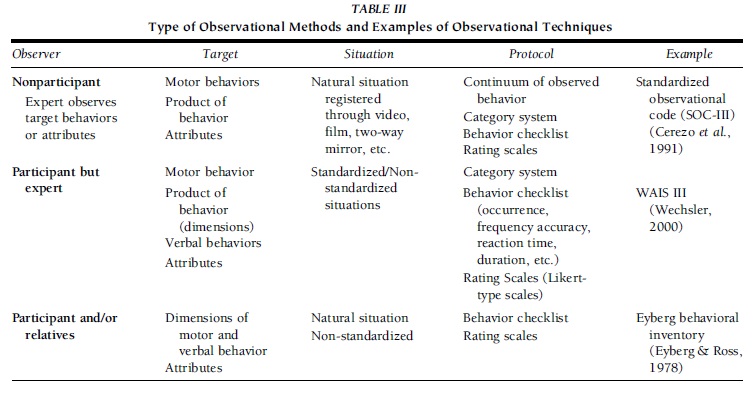

Like psychology in general, psychological assessment developed in association with different models or theoretical frameworks, which have given rise to different theoretical formulations, targets, methods, and objectives. Table II shows the psychological models that have had most repercussion in psychological assessment: trait, medical, dynamic, behavioral, cognitive, and constructivist.

TABLE I Principal Contributions in the History of Psychological Assessment from 1880 to 1950

TABLE I Principal Contributions in the History of Psychological Assessment from 1880 to 1950

2.1. Trait

As human beings display wide variability in the way they think, feel, and behave, one of the objects of inquiry in psychology has been individual differences in human characteristics related to intelligence or mental aptitudes, affect and emotions (aggressiveness, hostility, etc.), personality (extraversion, flexibility, etc.), psychopathology (depression, anxiety, etc.). All of these have constituted important targets for assessment.

The trait approach uses several data collection techniques, from questionnaires or standardized tasks to rating scales. It is, therefore, the trait approach that has inspired the most well-known psychometric tests. The main objective of this approach is to find the true score of a given subject in a specific trait or his or her true position in relation to a normative or standard group. In practical terms, these comparisons allow psychologists to describe and classify subjects with regard to a set of traits or medical conditions and to predict their future behaviors. The explanation objective would not be applicable to the trait model, for reasons of tautology.

2.2. Medical

Historically, the development of psychological assessment has been closely related to clinical settings. Therefore, from the outset a medical model emerged, focusing principally on mental disorders. Several classification systems have been developed, the most well-known being the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (currently the DSM IV-R) and the World Health Organization’s Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders (currently the ICD-10), both of which constitute descriptive category systems with no etiological bases (neuropsychological illness and assessment are not included in this medical approach).

The purpose of these classification systems is to provide clear descriptions of diagnostic categories of mental disorders in order to aid clinicians in diagnosing and referring to these disorders. From this perspective, and with the aim of establishing objective procedures for assessing mental and behavioral disorders, several tests have been developed (e.g., the Multiphasic Minnesota Personality Inventory). In sum, description and classification are the two main objectives of the medical model.

TABLE II Theoretical Approaches in Assessment: Model, Targets, Methods, Contexts, and Goals

TABLE II Theoretical Approaches in Assessment: Model, Targets, Methods, Contexts, and Goals

2.3. Psychodynamic

Included under the title of psychodynamic are a series of relevant targets: unconscious mental processes, conflicting attitudes generating anxiety, defensive mechanisms, and interpersonal patterns governed by developmental experience. As stated by Weiner (2003), the psychodynamic approach serves the purpose of elucidating ‘‘aspects of personality structure and personality dynamics in way that clarify the role of drives, conflict and defense, and object representations in shaping people are likely to think, feel and act’’ (p. 1012).

Throughout the history of psychological assessment, several instruments have been developed from a psychodynamic perspective. Perhaps the most well-known are projective techniques using semi-structured visual materials (such as the Rorschach tests or the thematic apperception test), drawing a specific object (draw-a-person, draw-a-tree, draw-a-family), and finally, approaches using verbal material (words, sentences, stories, etc.). The goals of the dynamic model include description and diagnosis as well as prediction and explanation.

2.4. Behavioral

The behavioral assessment approach has been defined in several ways throughout the 20th century, but three fundamental pillars of these definitions can be identified and reduced to the following: (1) human behavior can be explained by the interaction between the person (from a biological and psychological point of view) and the environment; (2) there are three different modes or systems: motor, cognitive, and psychophysiological; and (3) psychological problems have multiple causes, essentially environmental. Thus, as Table II shows, targets in behavioral assessment are motor, cognitive, and physiological responses, in addition to environmental conditions.

A methodological condition of behavioral assessment is that all targets should be assessed through the multimethod approach. Thus, assessment of behavioral and environmental conditions and their respective interactions takes place through observation (direct observation as well as observations by relatives), self-observation, self-report, and psychophysiological techniques. Finally, because behavioral assessment emerges from a clinical perspective, its objectives are description, prediction, functional explanation (need for treatment), and treatment evaluation. The main goals of the behavioral psychologist are related to the environmental or personal conditions that can be functionally linked to target behaviors and provide indications for the planning of treatment.

2.5. Cognitive

The cognitive model refers to two theoretical perspectives, the first related to the study of cognitive processes and the second associated mainly with therapy and treatment, under the assumption that cognitive processes or structures (or verbal expression of emotions) are causal aspects to be taken into account if the intention is to change behavior.

Table II shows the most important targets for the cognitive model: cognitive processes (such as attention, perception, learning and memory, language, and imagery), mental representations (e.g., visuospatial representations, automatic thinking), cognitive structures (cognitive abilities), and other cognitive constructs or forms of emotional expression. These processes, strategies or structures are assessed mainly through subjects’ performance in cognitive tasks. For example, attention can be measured by asking the subject to find a specific letter (e.g., ‘‘m’’) in a text, or to press a button when a specific cue appears on a screen (testing reaction time).

Cognitive processes or strategies can also be measured using meta-components. Thus, the subject may be asked to ‘‘think aloud’’ while solving a given task. The cognitive model also considers the meta-component of emotions, so that subjects may be asked to self-report what they feel in a particular situation. Finally, the objectives of the cognitive model—in the same line as those of the behavioral model—are the following: description (how the subject can be described on the basis of these processes and structures), prediction (what the subject can be expected to do on the basis of these processes), explanation (which processes may be controlling targets, so that they can be manipulated in order to change targets), and evaluation (to what extent treatment has produced the expected changes).

2.6. Constructivist

The constructivist theoretical approach to psychology stresses conceptual, epistemological, methodological, and ontological characteristics, as opposed to an objective and realistic view of the science. From this approach, all knowledge is considered as a social product, so that there cannot be any universal law or principles: subjective aspects and local custom or practices dictate. Therefore, targets must be selected for each individual and his or her specific way of constructing social reality, the meaning of life, or personal plans, or of producing personal constructs. Methods are idiographic rather than standard. Finally, utility is the most important characteristic of any assessment, as opposed to validity. Table II shows these idiographic targets making up the basic personal knowledge developed across the subject’s life span.

Several methods have been developed within the constructivist approach, all of which attempt to capture the essence of the person in question. Perhaps the most well-known is the repertoire grid technique. Originally developed by Kelly in the 1950s, several different versions have appeared over the last half-century, all with the basic purpose of assessing the subject’s personal constructs. Other methods involve the use of narratives developed by different authors, through which a sense of identity, coherence, meaning of life, and other personal phenomena can be assessed. With these narrative-based methods, the use of autobiography is an essential element for assessing these constructs. Finally, the data from these methods is analyzed through content analysis, which is essential to constructivist methodology, because hermeneutics is, basically, a system for discovering targets.

3. Methods And Techniques

Marx and Hillix made a distinction between scientific method, methods, and techniques (methodic techniques or instruments). While the scientific method is the basic strategy for the advancement of science (e.g., the hypothetico-deductive method), methods are general data collection procedures, and techniques can be defined as those specific instruments or tests developed for collecting data in a particular field.

An important body of knowledge within psychological assessment is the set of methodic techniques for data collection. However, before going on to describe these methods, it is necessary to first identify some general conditions of psychological assessment methods.

- Methods, techniques, and instruments should not be confused with psychological assessment. As stated previously, methods and tests constitute the tools for data collection and testing hypotheses, while psychological assessment is a lengthy process of problem-solving and decision-making.

- There are standard and non-standard methods. All techniques and instruments have a set of stimuli (questions, tasks, etc.), a set of administration procedures, and a set of responses; finally, subjects’ responses can be transformed into scores. Standard methods or tests are those that have a standard set of stimuli, standard administration procedures, and standard forms of obtaining subjects’ responses—responses that can be transformed into standard scores. Standard methods usually have sound scientific properties and present psychometric guarantees. These standard methods, which allow between-subject comparisons, are known as psychometric tests. But not all data collected in psychological assessment derive from standard methods.

- As described above, assessment targets are specific psychological characteristics (intelligence, cognitive skills, personality dimensions, behavioral responses, defense mechanisms, environmental conditions, etc.) with several degrees of inference. That is, the majority of these targets are psychological concepts that are operationalized by means of a given method, technique, or measurement device. Thus, all methods in psychology can be considered procedures for operationalizing a given psychological construct or target for assessment. Because each method has its own source

of error, the best way to conduct a rigorous assessment is to use several methodic techniques, tests, or measures or, in other words, to triangulate a given concept through multimethod. For example, if in assessing a particular personality construct (e.g., extroversion) the subject can be administered a standardized self-report, he or she can be given a list of adjectives, and his or her behavior can be observed in an analogue situation or by administering a projective technique.

With these three general conditions in mind, consider the broad categories in which psychological assessment methods can be classified: interview, observation, self-reports, and projective techniques. It should be borne in mind, however, that these four categories can themselves be divided into more specific sub-categories.

3.1. Interview

Interviewing is the most commonly used method in psychological assessment in all basic and applied fields: clinical, educational, work and organizations, forensic, laboratory, and so on. It has the broadest scope, so it can be used for assessing any psychological event (subjective or objective, motor, cognitive or physiological).

For assessment purposes, an interview is basically an interactional process between two people in which one person (the interviewer) elicits and collects information with a given purpose or demand, and the other person (the interviewee, client, or subject) responds or answers questions. The information collected can refer to the interviewee (motor, cognitive, or emotional responses) or to relevant others. Thus, the interview can be thought of as a self-report or as a report to or by another.

Because the interview is an interpersonal process, it has the following several phases:

- Interview preparation: Before starting an interview, the psychological assessor should plan the interview. What are the purposes of the interview? What are the subject’s characteristics? What format will the interview take? How long will the interview last?

- Interview starting point: A brief presentation by the interviewer about the purpose of the interview, what the interviewer is expecting, and the plans for the assessment process.

- Body of the interview: The interview is always led not only by the purpose of the assessment but also by the theoretical approach of the interviewer. These two principal conditions influence the content (what type of question) and the format (amount of structure in questions and answers) of the interview. By way of example, the main common and shared areas of an interview are as follows: sociodemographics, interview purpose or demand, family and social condition, education, work, interest and hobbies, health, beliefs, and values.

- Closing the interview: The interviewer closes the interview by briefly summarizing the data collected and describing the subsequent steps or actions.

There are several typologies of the interview depending on: (1) the structure of the questions and answers (structured, semi-structured, non-structured), (2) the context in which the interview takes place (clinical, personnel selection, counseling, forensic, etc.), (3) interviewer style (directive, non-directive), (4) theoretical perspective (dynamic or psychoanalytic, behavioral, phenomenological, etc.), and (5) number of subjects assessed (individual, group, family, team group, etc.).

The interview as an assessment method has several advantages and limitations, such as the following:

- It offers a situation in which subjects can act and interact with several verbal stimuli (or questions) and can be observed. Also, in this situation several interpersonal emotional relationships (interviewer– interviewee) develop that are highly relevant to forthcoming psychological actions.

- The interview is a broad technique for collecting data; that is, any condition or purpose (past or present; internal or external; descriptive, classificatory, or explanatory, etc.) can be assessed. Also, this flexibility of the interview allows psychologists to clarify a given situation or action of the subject.

- However, information collected in interviews may present considerable bias and error deriving from the interviewee, the interviewer, and the situation. Inter-interviewer agreement and test-retest reliability is relatively low, and validity depends on the construct assessed.

- Finally, as emphasized by Meyer et al., although most types of psychological testing—including the interview—show evidence of their predictive validity, the use of multimethods is essential in order to gain a complete understanding of each case.

3.2. Observational Methods

All psychological assessment contains observations. Indeed, as Anastasi (1988) stated: ‘‘a psychological test is essentially an objective and standardized measure of a sample of behavior’’ (p. 23). Thus, observation is one of the broadest categories in psychological assessment. Common intelligence tests (such as the Wechsler Intelligence scales), as well as cognitive or psychophysiological measurement using special equipment, can be used as observational procedures. In brief, an observational method consists of a set of data collection procedures containing a protocol with a predefined set of behavioral categories in which subjects’ behaviors are coded or registered. These behaviors are external, motor events observed in natural, analogue, or test situations; observation may sometimes involve the use of sophisticated equipment such as tachistoscopes, polyreactigraphs, or psychophysiological instruments that allow response amplification.

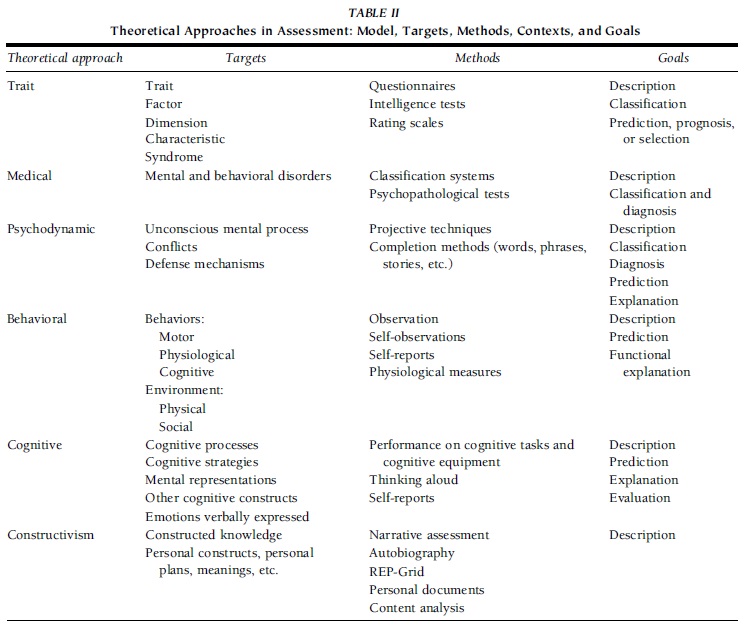

Observational methods have been classified depending on the following: (1) the observer: participant versus non-participant observer; (2) the target or observed event: overt event (motor response or stimuli parameter) versus subject’s attribute or molar characteristic of the observed situation; (3) the situation in which observations take place: natural versus artificial or standardized situations (or even with equipment amplifying the target); and (4) the protocol: coding system versus open description of the continuum of behavior. Table III shows examples of this classification system.

Observer, subjects and targets, and observational protocol are sources of bias of the observational assessment method. Below is a summary of how to maximize the accuracy of observational methods:

- Observer. Observational methods in psychology should maximize objectivity through the assessment of overt (observable) events, ongoing observer training, use of several observers, and checking of interobserver agreement.

- Subject observed. One of the most important biases of observational methods is subject reactivity. Reactivity can be minimized in various ways, such as use of natural settings, subjects being unaware, and long habituation periods.

- Observational systems. Coding or registration systems require well-defined targets and procedures, a small number of observation categories, and standard data about psychometric soundness.

3.3. Self-reports

As defined elsewhere, the self-report is a method for collecting data whose source is the subject’s verbal message about him or herself. Self-reports are the most common assessment procedures for collecting data in psychology and psychological assessment. Self-reports provide information about thousands of targets—from historical events to motor behaviors in the present situation, even subjects’ future plans. In fact, human beings can report on their private, unobservable, subjective world, their thoughts, and their emotions, as well as public observable events. This means that, in answering a verbal question, subjects may carry out certain mental operations (from remembering what they did a few minutes previously to inferring why they acted in a certain way a long time ago). Such operations interfere with the fidelity of self-reports.

TABLE III Type of Observational Methods and Examples of Observational Techniques

TABLE III Type of Observational Methods and Examples of Observational Techniques

Also, when a self-report or a set of self-reports is collected, psychologists can either take them as they are (from an isomorphic perspective) or make inferences from them after carrying out statistical manipulations (e.g., item aggregation or item anchoring in new scales). In other words, in order to test theoretical hypotheses, psychologists interpret the self-reports as indices of internal structures or processes, such as attitudes, personality characteristics, motives, and other intrapsychic concepts developed from trait theory, medical models, cognitive psychology, and/or dynamic theories. Thus, since the very beginning of scientific psychology, aggregates of self-reports assessed via questionnaires through inter-subject designs (subject aggregates) have been used as one of the main assessment methods for describing, classifying, predicting, and even (tautologically) explaining human behavior.

In psychological assessment, clients’ self-reports are collected in different formats. As already mentioned, interviews frequently represent the starting point and conclusion of a professional relationship in clinical, educational, and work settings. When self-reports are used as formal procedures for data collection, they imply a broad methodological category: interviews always involve self-reports, and self-observation and self-monitoring also require self-reports. Finally, self-reports can be obtained through questionnaires, inventories, or scales containing a set of relevant verbal statements and a variety of response formats (true or false options, checklists, scaled responses, etc.).

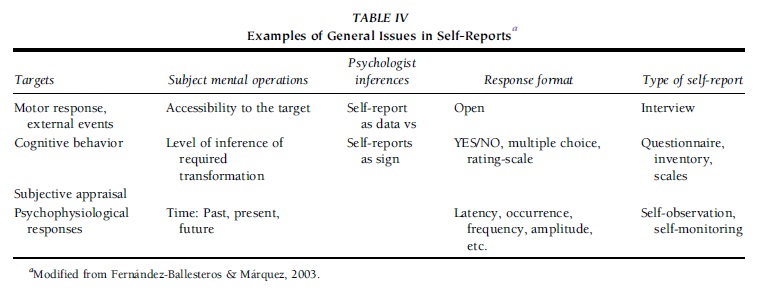

As emphasized elsewhere, self-reports have several sources of bias. Whatever the type of event reported— from objective events to subjective ones—several internal and external conditions, such as length of the question, formulation of the question, type of answer and response requested, and subject’s characteristics, strongly affect the fidelity of self-reports. Table IV shows examples of general issues related to self-reports. In summary, human beings are able to report on a myriad of events and are an important source of information; several assessment methods (such as interviews and self-observation, self-monitoring, questionnaires, inventories or scales) are based on self-reports. Even though self-reports have important sources of errors, so that self-report accuracy is threatened by several types of response distortions (positive and negative impression management, faking, acquiescence, and social desirability, among others), these can, at least partially, be measured and controlled. Finally, it is commonly accepted that self-report questionnaires can be optimized through various strategies, and that their accuracy can be maximized. When self-reports are taken as a source of behavioral information, the level of inference should be as low as possible, items should be as direct as possible, questions should be specific and with situational reference, the level of transformation of the information requested should be as low as possible, and finally, the information requested should refer, preferably, to the present.

TABLE IV Examples of General Issues in Self-Reports

TABLE IV Examples of General Issues in Self-Reports

3.4. Projective Techniques

According to Pervin (1975), a projective technique ‘‘is an instrument that is considered especially sensitive to covert or unconscious aspects of behavior, permits or encourages a wide variety of subject responses, is highly multidimensional, and evokes unusually rich or profuse response data with a minimum of subject awareness concerning the purpose of the test’’ (p. 33).

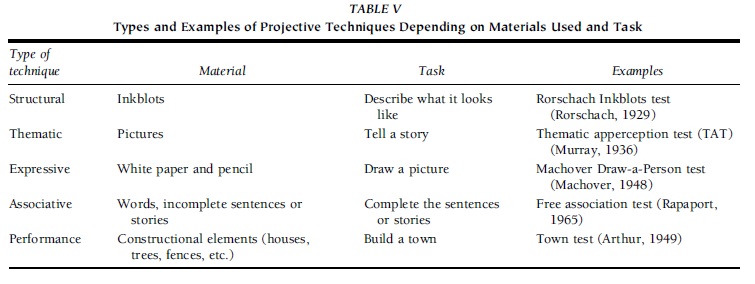

The basic assumptions of projective techniques are closely related to the psychodynamic model and psychoanalytic theory: (1) they involve the presentation of stimuli relatively free of structure or cultural meaning, consisting of inkblots, pictures, incomplete verbal sentences or stories, or performance tasks; (2) these materials allow subjects to express idiosyncratic and holistic aspects of their personalities, and allow the assessment of dynamic constructs as well as defense mechanisms against anxiety, and conscious as well as unconscious processes and structures; and (3) subjects are not aware of the purpose of the test and the meaning of their responses to the test. Table V shows four main categories of projective techniques that can be identified depending on the material used and the task involved.

Although projective methods have been widely used, they have received considerable criticism, and continue to cause controversy. In fact, all the characteristics of projective methods—ill-defined stimuli, idiographic responses, non-standardized procedures, and subjective evaluation—have contributed to a lack of psychometric soundness. In sum, much more research is required for projective methods to be used as scientific tools. Nevertheless, there is an exception, as Weiner (2001) has emphasized: ‘‘the Rorschach Inkblot Method has been standardized, normed, made reliable, and validated in ways that exemplify sound scientific principles for developing an assessment instrument’’ (p. 423).

4. The Process Of Assessment, Treatment, And Evaluation

As mentioned previously, assessment should not be confused with its methods and tests, nor with a specific applied setting (such as the clinical one). It begins when a client makes a specific demand of a psychologist in a given context. This demand triggers a long process of problem-solving and decision-making that requires a series of tasks ordered in a specific sequence. This sequence is dictated by the objectives the psychologist must fulfill: description, classification/diagnoses, prediction/prognosis, explanation, and control. When the demand is for control, implying the need for an intervention, evaluation is an operation to be performed for appraising the treatment, or testing the extent to which the targets have changed in the expected direction. Thus, when assessment is conducted in order to produce change and is followed by treatment, evaluation should be the final step in the assessment process.

TABLE V Types and Examples of Projective Techniques Depending on Materials Used and Task

TABLE V Types and Examples of Projective Techniques Depending on Materials Used and Task

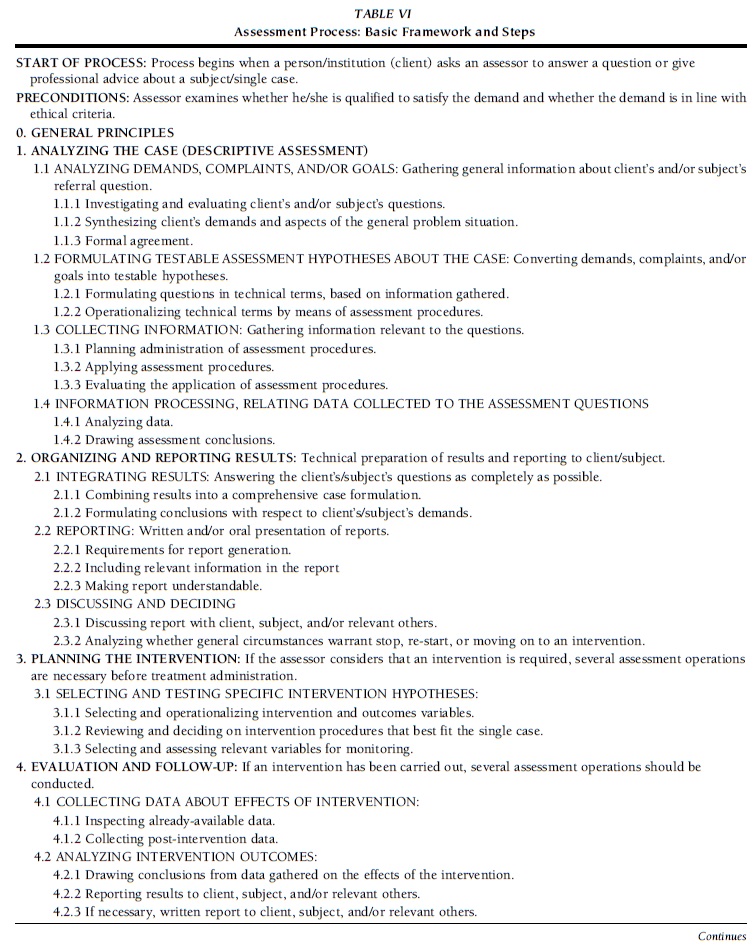

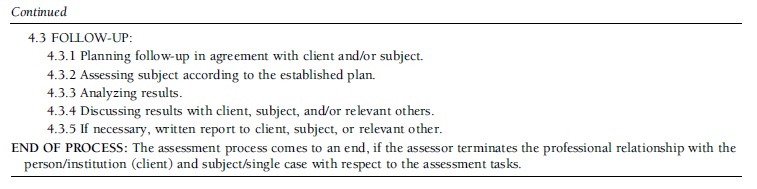

After 30 years of research into the assessment process, guidelines for the assessment process (GAP) have been set up in order to formalize it and published so that they can be discussed by the scientific community. The GAPs have been developed with the following purposes: (1) to assist psychological assessors in their efforts to optimize the quality of their work; (2) to assist the client coming from outside psychology in evaluating assessment tasks by allowing quality control; and (3) to facilitate the teaching of assessment, the standardization of practical considerations, and the design of advanced professional training programs.

Table VI presents the general framework of the assessment process. As it can be seen, the assessment, treatment, and evaluation process has four main steps: (1) analyzing the case; (2) organizing and reporting results; (3) planning the intervention; and (4) evaluation and follow-up. The two first phases deal with case formulation as well as with integrating, reporting, and discussing the case, and therefore refer to all assessment contexts (clinical, educational, work and industry, etc.), because description, classification/diagnosis, and prediction/prognosis are the assessment objectives in all cases. The third and fourth phases refer to those cases

demanding control and change and requiring explanatory assumptions, experimental designs, and, finally, treatment evaluation. Each step has several substeps, and from the substeps a set of 96 guidelines has been developed. The GAPs are procedural suggestions and should be taken as recommendations for helping assessors to cope with the complexities and demands of assessment processes in various applied contexts.

5. Conclusions

Psychological assessment is a subdiscipline of scientific psychology devoted to the study of a given subject with different purposes (describing, diagnosing, predicting, etc.) and in different settings (clinical, educational, etc.). Psychological assessment should not be confused with its methods or tests, since it involves a lengthy and complex process of decision-making and problem-solving that begins with the client’s demands. There are several theoretical models proposing specific targets, methods, and assessment objectives.

TABLE VI Assessment Process: Basic Framework and Steps

TABLE VI Assessment Process: Basic Framework and Steps

Psychological assessment uses a variety of methods: interview, observation, self-reports, and projective techniques. Some of these have standard sets of stimuli, administration procedures, and ways of measuring subjects’ responses and transforming them into standard scores; these methods are the well-known psychometric tests, but they are not the only means of collecting data in assessment. All assessment methods have particular sources of error, and all can be considered as fallible. The use of multimethod is highly recommended. Through the complex process of decision-making and problem-solving involved in psychological assessment, psychologists test hypotheses about the case, achieve assessment objectives, and draw certain conclusions in an attempt to respond to the demands of the client.

References:

- Arthur, H. (1949). Le village. Test d’ Activite´ Cre´ative. Paris: Pub.

- Baer, R. A., Rinaldo, J. C., & Berry, D. T. R. (2003). Self-report distortions. In R. Ferna´ ndez-Ballesteros (Ed.), Encyclopedia of psychological assessment (Vol. 2, pp. 861–866). London: Sage.

- Cook, T. D. (1985). Postpositivist critical multiplisms. In L. Shotland, & M. M. Marck (Eds.), Social science and social policy. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Cerezo, M. C., & Whaler, R. G., et al. (1991). SOC-III Standardized Observational Code. Madrid: MEPSA.

- Cronbach, J. L. (1975). Five decades of public controversy over mental testing. American Psychologist, 30, 1–4.

- Ericsson, K. A., & Simon, H. A. (1984). Protocol analysis. Verbal reports as data. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Eyberg, S. M., & Ross, M. (1978). Assessment of child behavioral problems. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 3, 113–116.

- Ferna´ ndez-Ballesteros, R. (2002). Behavioral assessment. In Smelser, N. J., & P.B. Baltes (Eds.), International encyclopedia of social and behavioral sciences. New York: Pergamon.

- Ferna´ ndez-Ballesteros, R. (2003). Self-report questionnaire. In S. N. Haynes & E. Heiby (Eds.), Comprehensive handbook of psychological assessment (Vol. 3, pp. 194–221). New York: John Wiley & Son.

- Ferna´ ndez-Ballesteros, R., De Bruyn, E. E. J., Godoy, A., Hornke, L., Ter Laak, J., Vizcarro, C., Westhoff, K., Westmeyer, H., & Zaccagnini, J. L. (2001). Guidelines for the Assessment Process (GAP): A proposal for discussion. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 17, 187–200.

- Ferna´ ndez-Ballesteros, R., & Ma´ rquez, M. O. (2003). Self-reports. In R. Ferna´ ndez-Ballesteros (Ed.), Encyclopedia of psychological assessment (pp. 871–877). London: Sage.

- Freixas, G. (2003). Subjective methods. In R. Ferna´ dez-Ballesteros (Ed.), Encyclopedia of psychological assessment. London: Sage.

- Goldfried, M. R., Stricker, G., & Weiner, I. (1971). Rorschach handbook of clinical and research application. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Goldstein, G., & Hersen, M. (1990). Historical perspectives. In G. Goldstein, & M. Hersen (Eds.). Handbook of psychological assessment (pp. 3–21). New York: Pergamon Press.

- Goldstein, G., & Beers, S. R. (Eds.). (2003). Intellectual and neuropsychological assessment. New York: Wiley.

- Haynes, S. N., & O’Brien, W. H. (2000). Principles and practice of behavioral assessment. New York: Kluwer.

- Haynes, S. N., & Heiby, E. M. (Eds.). (2003). Behavioral assessment. New York: Wiley.

- Machover, K. (1948). Personality projection in the drawing of the human figure. New York: Ch. C. Thomas.

- Marx, M. H., & Hillix, W. A. (1967). Sistemas y teor´ıas psicolo´ gicas contempora´ neas. (Contemporary psychological theories and systems). Buenos Aires: Paido´ s.

- Meyer, G. J., Finn, S. E., Eyde, L. D., Kay, G. G., Moreland, K. L., Dies, R. R., Eisman, E. J., Kubiszyn, T. W., & Reed, G. M. (2001). Psychological testing and psychological assessment. American Psychologist, 56: 128–165.

- Mischel, W. (1968). Personality and assessment. New York: Wiley. Murray, A. H. (1936). Exploration in personality. New York: Oxford Press.

- Neimeyer, G. J. (Ed.). (1993). Constructivist assessment. Newbury Park: Sage.

- Pervin, L. A. (1975). Personality, assessment, and research. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Rapaport, D. (1965). Test de diagno´ stico psicolo´ gico (Manual of Diagnostic testing). Buenos Aires: Paido´ s.

- Rorschach, H. (1921). Psychodiagnostik. Berne: Hans Huber.

- Segal, D. L., & Frederick, L. (2003). Objective assessment of personality and psychopathology: An overview. In Segal, D. L., & Hilsenroth, M. (Eds.), Personality assessment. New York: Wiley.

- Sundberg, N. (1976). Assessment of persons. New York: Pergamon.

- Schwartz, N., Park, D. C., Knauper, B., & Sudman, S. (1998). Cognition, aging and self-reports. Ann Arbor, MI: Psychology Press.

- Scriven, M. (1991). Evaluation thesaurus. London: Sage.

- Weiner, I. (2001). Advancing the science of psychological assessment: The Rorschach Inkblot method as exemplar. Psychological Assessment, 13, 423–433.

- Weiner, I. (2003). Theoretical perspective: Psychoanalytic. In R. Ferna´ndez-Ballesteros (Ed.), Encyclopedia of psychological assessment. London: Sage.

- Wiggins, J. (1973). Personality and prediction. Principle of personality assessment. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.