This sample Premenstrual Syndrome Treatment Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of psychology research paper topics, and browse research paper examples. This sample research paper on Premenstrual Syndrome Treatment features: 8600+ words (35 pages), an outline, and a bibliography with 8 sources.

Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS) refers to a condition that some women experience preceding the onset of their monthly menses. It consists of the cyclic recurrence of physical, psychological, and/or behavioral symptoms of sufficient severity that medical treatment is sought. Optimal care for the physical and psychological well-being of women who suffer from PMS is built on an understanding of the developmental aspects of women’s sexual health, including biological, psychological, and social /cultural influences.

Outline:

I. Historical Background

II. Normal Menstrual Cycle

A. Follicular Phase and Ovulation

B. Luteal Phase

C. Influences on the Normal Menstrual Cycle

D. Variability in the Normal Menstrual Cycle

III. Developmental View ofWomen’s Health and the Menstrual Cycle

IV. Phenomenology of Premenstrual Syndrome

A. PMS Symptoms and Their Timing

B. Prevalence

C. Etiology and Risk Factors

V. Restoring Mental and Physical Health Related to the Menstrual Cycle

A. Prevention

1. Early Developmental Experiences and Health

2. Women’s Development within the Context of the Family

3. Women’s Suffering in Relation to Contemporary Circumstances and the Effects of Culture

B. Diagnosis

C. Appropriate Treatment Interventions

1. For Women Thought Not to Have PMS

2. For Women Diagnosed with PMS

I. Historical Background

As far back as the time of Hippocrates, physicians have attempted to describe the relationships between menstruation and the subjective experiences, moods, and behavior changes ofwomen. Over the past 24 centuries, ‘‘morbid dispositions of the mind’’ and ‘‘madness’’ in the form of mania, delusions, ‘‘nervous excitement,’’ hallucinations, ‘‘unreasonable appetites,’’ and suicidal impulses have been attributed to the cyclic menstrual patterns of women. Although much remains to be understood, our clinical and scientific interest in these relationships has grown in modern times. Robert Frank coined the term ‘‘premenstrual tension’’ and offered this remarkable description of the problem in 1931 (p. 1054):

A feeling of indescribable tension from 10 to 7 days preceding menstruation which, in most instances, continues until . . . menstrual flow occurs. These patients complain of unrest, irritability, ‘‘like jumping out of their skin.’’ . . . [T]heir personal suffering is intense.

Premenstrual tension later became known as premenstrual syndrome or PMS. In particular, the work of Katharina Dalton in England, beginning in the 1950s and ongoing today, established PMS as a legitimate health condition of women, worthy of medical attention and scientific investigation (see Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS) by Katharina Dalton). A conference convened by the National Institute of Mental Health in 1983 established diagnostic guidelines for PMS and affirmed the interest of mental health professionals in the mood symptoms experienced premenstrually by many women. In 1987, Late Luteal Phase Dysphoric Disorder (LLPDD), a more narrowly defined syndrome than PMS, was included as a proposed clinical diagnosis in an appendix of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IIIR). DSMIV, published in 1994, replaced this terminology and classified Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder as a clinical diagnosis under the rubric of ‘‘Depression Not Otherwise Specified.’’

After decades of research, PMS remains a puzzle with respect to etiology, physical and psychological correlates, risk and protective factors, and treatment. The true prevalence of PMS remains uncertain, the relative contributions of ‘‘nature’’ and ‘‘nurture’’ to PMS symptomatology have not been determined, and the reasons why only some women develop PMS have not been fully established. We have learned to some extent, however, what PMS is not: PMS is not the result of abnormal menstrual cycles or of abnormal absolute levels of ovarian hormones. It is not solely the result of attributional bias. Moreover, PMS is not a condition relieved uniformly by a single treatment approach such as hormonal therapy or psychiatric medications. After years of inquiry, it appears that PMS is the result of complex interactions among biological, psychological, social, and cultural influences within the lives of women.

For this reason, women’s health related to PMS may best be understood from a multidimensional perspective. This research paper outlines an approach to PMS that focuses on the normal menstrual cycle and the distinct biological, psychological, and social /cultural issues in women’s development, and includes a review of the phenomenology of PMS. With this foundation, we describe strategies for restoring mental and physical health related to the menstrual cycle through prevention, accurate diagnosis, and appropriate treatment interventions.

II. Normal Menstrual Cycle

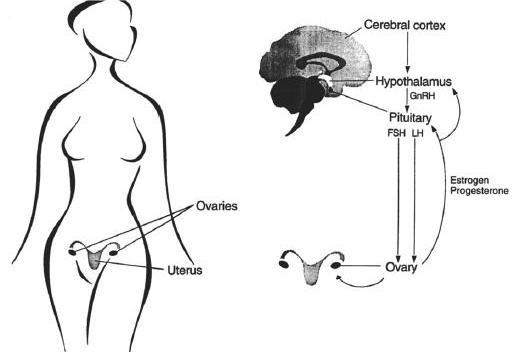

The normal menstrual cycle is an intricately orchestrated, neatly timed physiologic process occurring in women from menarche until menopause. Each cycle revolves around development of an ovarian follicle and the preparation of the uterus, followed by ovulation and the transformation of the ovarian follicle into the corpus luteum, which is necessary for sustaining a pregnancy should fertilization and embryo implantation occur. In the absence of pregnancy, the menstrual cycle ordinarily lasts 26 to 32 days (a range of 21 to 36 days), with women between the ages of 20 and 40 having the greatest regularity in cycle length. The menstrual cycle’s three distinct phases relate primarily to hormonal changes and events at the hypothalamus and pituitary regions of the brain, the ovary, and the uterus (Figures 1 and 2). The cycle is also influenced by the limbic region of the central nervous system, the adrenal and thyroid glands, the pancreas, and exogenous hormones or medications.

Figure 1. Anatomy and physiology of the menstrual cycle. GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone.

A. Follicular Phase and Ovulation

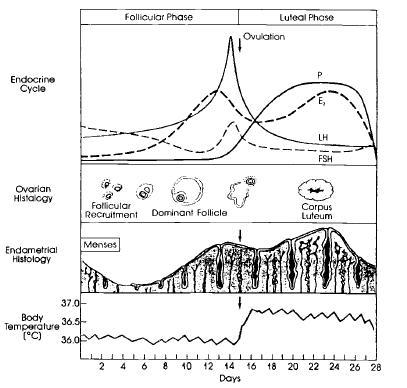

The follicular phase begins on the first day of menstruation and lasts until approximately Day 14, based on a 28-day cycle. During this phase, a number of ovarian follicles, each typically containing a single ovum, develop under the influence of follicular stimulating hormone (FSH) produced by the anterior pituitary, a deep, midline endocrine organ in the brain. This hormone is produced and delivered in response to the pulsatile release of a neurohormone, gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH), which is produced in the medial basal region of a second brain structure, the hypothalamus. The developing follicles, in turn, produce estrogen, which has three main effects: it dampens the further release of FSH by the anterior pituitary; it, along with GnRH, stimulates the production and gradual release of luteinizing hormone (LH) by the anterior pituitary; and it stimulates the growth of the uterine lining or endometrium. Over the course of 2 weeks, one of the ovarian follicles matures more than the others in that it is larger, has evidence of more mitotic and biosynthetic activity, and has greater vascularization. This ‘‘dominant’’ follicle progresses through three phases (preantral, antral, and preovulatory) and manufactures increasing amounts of estrogen and, to a lesser extent, progesterone. The other follicles gradually and irreversibly decline.

Toward the end of the follicular phase, a rise in progesterone and surges of estrogen, LH, and FSH take place, resulting in ovulation. Estrogen peaks 24 to 36 hours prior to ovulation, whereas LH and FSH peak roughly within 10 to 12 hours of ovulation. Luteinizing hormone stimulates the initiation of oocyte meiosis, leutinizes the granulosa cells of the follicle, and promotes progesterone and prostaglandin synthesis within the follicle. Progesterone potentiates estrogen effects and also triggers the FSH surge and activates prostaglandins and enzymes present in the follicle. This allows the follicular wall at the edge of the ovary to rupture. Influenced by hormones and chemicals in the immediate locale, the ovum then detaches from its anchor within the ovarian follicle. The release of the ovum from the ovary, allowing it to travel down one of the two fallopian tubes for possible fertilization, is defined as ovulation.

A number of physical and psychological findings have been noted during the follicular and ovulation phases of the menstrual cycle, including endometrial breakdown and sloughing during the initial 2 to 8 days of the follicular phase (i.e., menses), followed by proliferation, vascularization, and differentiation of the endometrium for implantation; increased production of thin, relatively alkaline cervical and vaginal mucus in response to raising estrogen levels; an initial sustained decrease in basal body temperature, followed by a temperature rise shortly after ovulation; regular alterations of electrolyte composition of urine and saliva; and a heightened sense of personal well-being, enhanced sensory perceptions, and, perhaps, somewhat improved cognitive task performance throughout the follicular phase.

Figure 2. The normal menstrual cycle. Hormonal ovarian, endometrial, and basal body temperature changes throughout the normal menstrual cycle. P, progesterone; E2, estradiol; LH, luteinizing hormone; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone.

B. Luteal Phase

The luteal phase occurs after ovulation, spanning approximately Days 15 through 28 of the menstrual cycle. Once the ovum has been released, the ruptured follicle becomes the corpus luteum, or ‘‘yellow body,’’ named because of the high concentrations of lipids it contains. Its granulosa cells hypertrophy and produce high amounts of progesterone, estrogen, and androgens necessary for sustaining a pregnancy if fertilization and implantation have occurred. At such concentrations, these hormones serve to decrease GnRH secretion by the hypothalamus. They also stimulate the endometrium to become edematous and to undergo glandular proliferation over the 7 days after ovulation. In addition, progesterone reduces some of the pituitary effects of estrogen by decreasing estrogen receptors in this brain structure.

In the absence of pregnancy, approximately 10 to 14 days after ovulation, the corpus luteum regresses and becomes a fibrotic, hyalinized region of the ovary, called the corpus albicans. Progesterone and estrogen concentrations gradually decrease. These events trigger a number of endometrial responses. Local vasomotor reactions within the spiral arterioles of the uterine lining cause endometrial ischemia. Local prostaglandin synthesis increases, augmenting uterine contractility. Menstruation begins as necrotic tissues slough away and blood from interstitial hemorrhaging enters the uterus. The sustained low levels of estrogen and progesterone stimulate the hypothalamus to release GnRH and the pituitary to secrete FSH and LH, triggering the development of another set of ovarian follicles and setting into motion the next menstrual cycle.

The premenstrual phase spans the 5 to 7 days before menstruation, and thus occurs within the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. A wide range of symptoms, such as increased fluid retention, fatigue, breast tenderness, headaches or other pain syndromes, mood fluctuations, and subjectively increased appetite, have been associated with this segment of the normal menstrual cycle. Only when it is so severe that patients’ daily functioning is affected and health care is formally sought for this problem can the diagnosis of PMS be made.

C. Influences on the Normal Menstrual Cycle

Elements that can modify or disrupt the normal menstrual cycle are many and often interrelated. For example, limbic system neurotransmitters (such as dopamine) appear to inhibit GnRH release by the hypothalamus, whereas norepinephrine stimulates GnRH output. In addition, as the ovarian corpus luteum deteriorates, its decrease in estrogen and progesterone production leads to a reduction in hypothalamic endorphin release. This, in turn, triggers greater GnRH, LH, and FSH production and causes follicle maturation early in the next cycle. Psychological and physical stresses may also modify the menstrual cycle through increased secretion of endorphins stimulated by increased corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH). This leads to a decrease in GnRH release, which interferes with ovulation. Abnormalities in adrenal steroid synthesis or insufficient production of hormones by the thyroid (thyroxin) or the pancreas (insulin) may result in anovulation and infrequent menses, although the mechanisms of action are unknown. Estrogen itself is associated with increased secretion of growth hormone, prolactin, ACTH, and oxytocin controlled in concert by the hypothalamus and the anterior and posterior regions of the pituitary. Genetic syndromes affecting hormone and steroid synthesis or chemical metabolism similarly will influence menstrual cycles. Beyond internal chemical influences, exogenous hormones and medications may induce or prevent ovulation through a number of mechanisms, affecting the length and timing of the menstrual cycle. These richly varied and interconnected processes suggest how women with different central nervous system lesions, life stresses, genetic disorders, endocrine dysfunction, and medical illnesses all may develop interrupted menstrual cycles.

D. Variability in the Normal Menstrual Cycle

The normal menstrual cycle differs between women as well as across an individual woman’s lifetime. This variability is shown in many ways: the length of menses (normal range of 2 to 8 days) and the menstrual cycle (normal range of 21 to 36 days); its synchronization with other women in close proximity; symptoms and signs associated with the premenstrual phase and menstruation; the level of interference caused by external factors such as physical illness or extreme exercise; the effects of emotional stress, nutritional deficiencies, medications, and hormonal disruptions; the numbers of follicles that mature during each cycle as a woman ages; and changes that occur at different life stages or with pregnancy and lactation. There is considerable variation that falls within the range of ‘‘normal’’ menstrual cycle experiences. For this reason, recognizing the premenstrual syndrome can be especially challenging.

III. Developmental View of Women’s Health and the Menstrual Cycle

Development is an orderly pattern of changes within an individual occurring over time, each stage is built upon and shaped by earlier ones. Development is influenced by the unique relationship between an individual’s biology and experiences of the self, of others, and of the world. These factors deeply affect personal attributes such as temperament and personality; cognitive capacities including learning, memory, and intelligence; the meanings given to sensations, relationships, and events in life; and one’s sense of the self within a specific familial, social, and cultural setting. With each stage of development, aspects of the individual are reconfigured within the current context. Thus, each moment offers indications of both one’s distinct personal history and unique adaptation to the present.

A woman’s development begins at conception (Table I). The potential for normal female sexual differentiation is genetically determined by the presence of two X chromosomes and the absence of a Y chromosome in the embryo. The actual course of development, however, is affected by a series of critical periods in the subsequent growth of each individual.

During critical periods in the sequence of development, biology and experience work in concert to organize and delimit the ‘‘choices’’ of an organism. The potential for ovaries and female external genitalia is made possible by the XX genotype. Female fetal tissues will not develop into these anatomic structures, however, unless sex hormones are present in specific proportions in the fetal environment at certain times. Abnormal proportions of fetal hormones or chemical exposures may alter subsequent physical development and sexual behavior, as evidenced by animal experiments in which hermaphroditic external genitalia or male-type sexual behaviors have been induced in genotypic females through fetal androgen exposure. In addition to animal models, patients with anomalous sexual development have clearly demonstrated that aspects of sexual differentiation may be irreversibly ‘‘settled’’ in an individual once a critical period has passed. Analogously, differential androgen production in men and women is implicated in central nervous system sexual differences evident in brain structure, physiology, and vascular patterns. Finally, the clinical observation that mothers, daughters, and sisters often resemble one another with respect to their ages at onset of menarche and at onset of menopause suggests that genetic and other early developmental factors may affect later events of sexual maturation. Further investigation is needed to understand the mechanisms that contribute to critical periods in sexual development.

In infancy and childhood, girls learn through experiencing sensations, through using their muscles, and through relating to others. A girl’s sense of herself, her body, and her core gender identity (i.e., the earliest feeling of belonging to one sex) emerges in a familial context of attachment, nurturance, affiliation, intimacy, and identification. Children ideally develop a feeling of fundamental trust through the safety and predictability present in this context; alternatively, they may develop a deep sense of apprehension and vulnerability based on their early experiences. Over time, children become acutely aware of certain social and cultural expectations that may surround gender roles as their bodies grow and mature. Anatomic differences between boys and girls give rise to differences in self-concepts, affirmed or altered by learning and observation. Over time, children also express curiosity and become more comfortable with their anatomic sex. Physical well-being during early childhood may be especially important to later health and illness patterns with respect to recognition of bodily discomfort, interpretations of pain, expression of emotional distress through physical complaints, and external validation or reinforcement of symptomatology.

Puberty marks the beginning of adolescence, bringing with it a number of dramatic physical changes such as breast development, growth of pubic and axillary hair, hip widening, and acne. Menarche normally occurs between the ages of 10 and 16, approximately 2 years after the onset of puberty. Of all of the pubertal changes, the start of menstruation is perhaps the most meaningful event, in that it represents a clear passage into womanhood physically and psychologically. Menarche may be exciting, affirming, frightening, awkward, or all of these and other feelings simultaneously. Although menarche does not itself indicate reproductive maturity, it does signify its future promise. The temporal pattern of a young woman’s menstrual cycle may be inconsistent in adolescence, especially in connection with erratic nutrition and exercise patterns that in some cases are pathological (e.g., anorexia nervosa, bulimia). Within a few years, however, in the absence of severe physical and psychiatric pathology, menses normally tend to fall into a more regular rhythm with predictable ovulation.

The psychological work of adolescence is equally remarkable. A young woman’s tasks include making changes in her self-image and body-image, exploring her gender identity and sexual orientation, learning about emotional and physical intimacy in peer relationships, becoming more autonomous and feeling competent in familial and other contexts, and forming a personal value system around relationships, school performance, sexual behavior, and other issues such as drug use and the problems that accompany sexual activity. Through such experiences, a young woman makes the transition from her family of origin to greater independence and prepares for the full responsibilities of adulthood.

During young and middle adulthood, a number of psychological and physical events of developmentmay occur. At this time, women tend to become more comfortable with themselves and begin making committed attachments, marriages, and partnerships. They learn increasingly about their sexuality, sexual orientation, and personal health issues. Their menstrual cycles also become more settled and predictable. Menstruation may be viewed more positively than at other times as a link to desired fertility. Difficult menstrual patterns (e.g., premenstrual magnification, premenstrual exacerbation of other conditions, or premenstrual syndrome) may also become clearer as women gain greater insight into their cyclic symptoms. In addition, much of women’s lives during young and middle adulthood may be affected by reproductive issues such as contraception, pregnancy and lactation, miscarriage and termination of pregnancies, infertility, and child-rearing, all of which may affect menstruation patterns and related cyclic mood and behavioral symptoms. A woman’s view of her responsibilities in family and professional relationships may become consolidated during her 20s through 40s as she practices these skills as a wife or partner, a parent, a daughter, a sister, a neighbor, a citizen, and a worker. Taken together, such everyday experiences greatly influence a woman’s tolerance and perception of physical symptoms, energy level, willingness to seek health care, self-esteem, libido and sexual desire, comfort, and self-understanding.

In later adulthood, women experience physiological, anatomic, and emotional changes throughout their postreproductive years. Menopause ordinarily occurs in women aged 45 to 55, preceded by approximately 2 years of lengthened or missed menstrual cycles and occasional spotting. Premenstrual syndrome, per se, tends to worsen as menopause approaches and to remit after menopause. During this phase of life, women often experience medical illness, undergo surgical interventions, and receive medications that affect menstrual function and general physical well-being such as hormone replacement. During this period, women also face transitions in family relationships, including children moving away, divorce, or the death of a spouse or parent. Over the 20 or more years beyond menopause, many adaptations are required as women experience changes in intimate relationships, social and societal roles, and personal identity. If loneliness was present earlier in life, it may deepen in the postmenopausal years. Despite such difficulties, for many women, this period allows for creativity, generativity, and freedom not possible at a younger age. Ideally, late in life, women will feel a sense of integrity and completeness about all of their experiences in relation to their biological natures, their personal identities, and their familial and societal roles.

Table I. Menstrual Cycle and Sexual Development of Women throughout the Life Span

Prenatal

• Establishment of sexual genotype (XX or XY) at conception

• Some evidence that genetic factors influence growth, age at menarche, and, possibly, future menstrual characteristics

• Intrauterine environment (e.g., hormones, receptors, timing of exposures) influence anatomical and functional fetal differentiation

Infancy/childhood

• Emergence of core gender identity, i.e., the earliest sense of belonging to one sex, during infancy

• Affiliation, attachment, and identification with parents, other family members, care providers

• Physical growth and development (prepubertal); comfort with one’s anatomic sex; emergence of sexual orientation

• Exposure to emotional, familial, cultural, and social expectations related to gender

• Sexual self-stimulation and curiosity, sexual play

• Sense of fundamental safety or vulnerability; potential for sexual abuse and exploitation

Adolescence

• Physical changes associated with puberty, including breast development, growth of pubic and axillary hair, menarche (ages 10–18), hip-widening, vaginal discharge, and acne

• Settling into a regular menstrual pattern

• Self-image and body-image changes; for some, risk of eating disorders, other maladaptive patterns

• Gender identity and sexual orientation exploration

• Interest in romantic and sexual relationships and curiosity about sexuality, sexual sensation

• For some, initiation of genital sexual activity, including intercourse

• Learning surrounding emotional and physical intimacy in peer relationships

• Making choices with potentially long-range consequences such as drug use and risky sexual activity

• Forming a value system around personal responsibility, sexuality, relationships, and cultural precepts

• Dealing with potential consequences of initiating sexual relationships, including pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases

• Making the transition to adulthood and practicing being separate from the family of origin

Young and middle adulthood

• Establishing a regular menstrual pattern

• Active exploration of sexuality in relationships, learning and practicing with enhancement of sexual satisfaction through time

• Coping with physical and emotional risks accompanying sexual activities, including coercion, sexaully transmitted diseases, pelvic inflammatory disease, cervical cancer, domestic violence

• Making committed attachments, marriages, partnerships

• Becoming more comfortable with gender identity and sexual orientation

• Dealing with reproduction issues such as contraception, pregnancy, miscarriage, infertility, premature menopause

• Physiological and psychological changes surrounding pregnancy, lactation, and child-rearing, including alterations in libido, energy, physical comfort, desire, self-image, meaning of relationships

• For some, manifesting psychiatric illness such as anxiety, depression, late luteal phase dysphoric disorder, sexual dysfunction, psychosis, substance abuse

Later adulthood

• Physiologic, anatomic, and self-image changes associated with menopause

• Maintenance of menstruation by means of exogenous hormones

• Facing transitions in relationships, including children moving away, divorce, death of parents

• Dealing with medical illness, medications, and surgery (including hysterectomy) that affect self-image and sexual functioning

• For many, new possibilities and creativity in postreproductive years

Elderly

• Continuing interest in intimate and sexual relationships

• Physical and emotional changes accompanying aging, including the slowing of sexual responsiveness, lessened physical comfort, and embarrassment

• For many, the loss of intimate partner to death and a sense of loss in family, social, and societal roles

• Dealing with medical illness, medications, and surgery that affect sexual health, function, and self-image

• Sense of integrity and wholeness with respect to one’s life, including one’s sexuality

IV. Phenomenology of Premenstrual Syndrome

A. PMS Symptoms and Their Timing

An immense number of symptoms have been attributed to PMS (Table II). The most common complaints include physical symptoms (breast swelling and tenderness, abdominal bloating, headaches, muscle aches and pains, weight gain, and edema), emotional symptoms (depression, mood swings, anger, irritability,and anxiety), and others (decreased interest in usual activities, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, increased appetite and food cravings, and hypersomnia or insomnia).

Four temporal patterns have been described for PMS. Symptoms can begin during the second week of the luteal phase (about Day 21). Alternatively, they can begin at ovulation and worsen over the entire luteal phase (about Day 14). In both of these patterns, symptoms remit within a few days after the onset of menses. Some women experience a brief episode of symptoms at ovulation, which is followed by symptom-free days and a recurrence of symptoms late in the luteal phase. Women who seem to be most severely affected experience symptoms that begin at ovulation, worsen across the luteal phase, and remit only after menses ceases. These women commonly have only 1 week a month that is symptom-free. It is unclear whether these four patterns represent distinct subtypes ofPMSor whether they correspond to other conditions. These four patterns of symptoms must be differentiated from underlying illnesses that either are precipitated during the premenstrual phase or demonstrate a cyclic waxing and waning of intensity related to menstruation. They must also be differentiated from other problems associated with menses, including pelvic pain with menstruation (dysmenorrhea), infrequent menses (oligomenorrhea), absent menses (amenorrhea), frequent menses (metrorrhagia), and excessive bleeding with menses (menorrhagia).

The course and stability of PMS over time has not been systematically characterized. It has been observed that PMS can begin any time after menarche, but women most frequently seek treatment for their symptoms in their thirties. Symptoms are believed to remit with conditions, such as pregnancy, that interrupt ovulation. Women generally report that their symptoms worsen with age until menopause, when PMS usually ceases.

Table II. Examples of Premenstrual Symptoms

- Abdominal cramps

- Aches or pains

- Anger

- Anxiety

- Bloating

- Breast tenderness

- Clumsiness

- Concentration problems

- Confusion

- Cravings (e.g., carbohydrate, salt)

- Depression

- Excessive sleepiness

- Fatigue

- Forgetfulness

- Headaches (migraine, tension)

- Hot flashes

- Insomnia

- Impulsivity

- Irritability

- Moodiness

- Rapid shifts in emotions

- Swelling (hands, feet)

- Weight gain

B. Prevalence

The true prevalence of PMS is unknown because a prospective, community-based epidemiological study of the syndrome has not yet been conducted. Nevertheless, it is estimated that 20 to 40% of women report some premenstrual symptoms and that 5% of women experience some degree of significant impairment of their work or lifestyle. These figures are consistent with retrospective epidemiological survey data that report the prevalence of PMS to be 6.8% and with two population-based studies that report the prevalence of PMS to be 4.6% and 9.8%, respectively.

The frequency of PMS in different cultures remains undetermined, although at least 24 countries have published studies of PMS. Retrospective surveys of premenstrual symptoms have led to the belief that PMS affects women equally, regardless of socioeconomic status or culture; this belief is a hypothesis that merits further investigation.

C. Etiology and Risk Factors

The etiology of PMS and the factors that place a woman at risk for developing PMS remain uncertain. Etiologic hypotheses that have been proposed include abnormalities in hormonal secretory patterns (ovarian steroids, melatonin, androgens, prolactin, mineralocorticoids, thyroxin, insulin), neurotransmitter levels (biogenic amines such as epinephrine and norepinephrine, endogenous opioids), circadian rhythms (temperature, sleep), prostaglandins, vitamin B6 levels, nutrition, allergic reactions, stress, and other psychological factors. Although investigators may advocate vehemently for one or more of these possibilities, no single, fully explanatory mechanism has been isolated as yet. Furthermore, there are physiological and behavioral correlates of menstrual cycle rhythms such as increases in appetite premenstrually and abdominal discomfort during menstruation that are present in women without PMS. These findings have led to the belief that the etiology of PMS resides in the interaction of many different factors that culminate in symptom expression.

Although not demonstrated conclusively, research suggests that genetic factors may place a woman at a relatively greater risk for the development of PMS or for greater severity of PMS symptoms. In one small study conducted by Dalton and colleagues, the pattern of identical twins both having PMS was found to be significantly higher (93%) than in nonidentical twins (44%) and in nontwin control women (31%). A questionnaire survey of 462 female volunteer twin pairs published by Van den Akker and colleagues further supports the possibility that a genetic predisposition for PMS exists. Similarly, evidence from developmental studies suggests a familial pattern as well. For instance, in a study of 5000 adolescent Finnish girls and their mothers, daughters of mothers with premenstrual ‘‘tension’’ were more likely to complain of PMS than were daughters of mothers who were symptom-free. In addition, 70% of daughters whose mothers had nervous symptoms in this study also had symptoms themselves, whereas only 37% of daughters of unaffected mothers experienced symptoms. These studies represent a crucial step toward clarifying the contributions of nature and nurture to the expression of PMS.

As with all medical illnesses, a number of psychological factors may contribute to PMS symptomatology in women. A young woman’s symptoms and signs around menstruation may be interpreted as pathological or as normal according to her internalized sense of sexual health drawn from early family experiences, societal views of gender, and other influences. The ability to cope effectively with severe PMS symptoms may be hampered by the extraordinary stresses (e.g., balancing family and work responsibilities, single-parenting, dealing with financial pressures, or surviving the loss of a spouse) that have become commonplace in women’s lives. Sadness and anxiety, vulnerability, and helplessness can become linked to a woman’s experience of her menstrual cycle and may be attributed to PMS. Moreover, if a woman has disowned or devalued parts of herself, if she has endured interpersonal violence or other trauma, her suffering may be expressed symbolically through PMS symptoms. In summary, it is likely that the etiology of PMS resides in the interaction of multiple influences from a woman’s biology, developmental events, and contemporary life circumstances which find expression in a unique cultural context.

V. Restoring Mental and Physical Health Related to the Menstrual Cycle

Mild warning signs of the onset of menstruation, as Dalton describes (see Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS)), are a valuable gift of nature. The need to restore mental and physical health related to the menstrual cycle through formal clinical intervention occurs only when these warning signs, or the experience of menstruation itself, become especially uncomfortable. In such cases, it is essential to take a clinical approach that remains mindful of the objectives in providing clinical care for women’s sexual health (Table III) and involves three elements: prevention, accurate diagnosis, and appropriate treatment interventions.

Table III. Objectives in Caring forWomen’s Health: PREVENTION

P Prevention—Prevention of illness, high-risk behaviors, stresses associated with sexuality

R Resources—Provision of resources for safety, learning, and social support

E Evaluation—Evaluation of signs and symptoms, sexual history and practices

V Violence—Exploration of issues surrounding violence and coercive sexuality

E Esteem—Assessment of esteem and well-being associated with sexuality and intimacy

N Nonjudgmental—Communication in a nonjudgmental, open manner

T Treatment—Prompt and appropriate treatment of identified illnesses

I Intervention—Intervention when necessary to ensure physical and emotional safety

O Options—Provision of therapeutic options surrounding sexual health (e.g., contraception)

N Nonexploitative—Establishment of a nonexploitative, ethical relationship with patient

A. Prevention

As evidenced by the virtual elimination of smallpox, polio, and measles in developed countries because of routine immunization practices, primary prevention may offer the greatest promise for many medical conditions that cause tremendous suffering. In the absence of greater clarity and specificity concerning the etiology of PMS, the creation of reliably effective primary, secondary, and tertiary preventive health strategies for this syndrome is difficult. Nevertheless, early work suggests that prevention of PMS hinges on two objectives: the pursuit of overall good health, including sexual health, and the process of unearthing and clarifying patient beliefs that may interfere with personal well-being. Education related to biological or psychological aspects of prenatal care, family patterns and roles, and social /cultural ideas may address these goals and may diminish the likelihood of the initial development of PMS (primary prevention) and increase the chances of recognizing, appropriately treating, and reducing the suffering associated with PMS (secondary and tertiary prevention).

A woman who experiences uncomfortable physical, psychological, and/or behavioral signs and symptoms in relation to her menstrual cycle should thus be understood with respect to her biological nature and the psychological aspects of her life experiences and her contemporary circumstances. In so doing, the clinician can pursue educational interventions that may decrease the incidence (number of new cases each year in a given population) of PMS, improve recognition of PMS, and reduce the morbidity associated with PMS. Three illustrations of preventive educational interventions follow.

1. Early Developmental Experiences and Health

Premenstrual syndrome differs from other endocrinerelated mood disorders, such as depression induced by diabetes or hypothyroidism, in that blood hormone levels are essentially normal. These findings suggest that PMS may have special psychobiological features, and these should raise questions about the relationship of PMS to childhood health and nurturing. Early evidence indicates that tactile stimulation beforeweaning, for example, leads to antibody production, thought to be essential for proper functioning of the immune system in infancy and for immune and pituitary–adrenal activation in adulthood. Research should thus focus on the impact of early development on immunological and neuroendocrinological patterns that may permanently influence the person’s susceptibility to or immunity from illness. As these complex issues become clarified, clinical attention should focus on the quality of the caregiver–infant relationship to ensure optimal maturation and enhanced neuroendocrine/immune function later in life. This example of early infant care is a valuable paradigm for exploring the interplay of biological, psychological, and social /cultural factors in preventive health.

2. Women’s Development within the Context of the Family

Prevention related to the woman’s personal developmental experiences focuses first on family. The family is the predominant institution in which growth and development of each individual member occurs and in which social and cultural values are translated into everyday terms. A girl’s identity develops out of a sense of connectedness with others, first as a sense of being like and connected with her first caregiver, and later as a sense of being connected with others. By 18 months, a girl has learned the label, ‘‘I am a girl.’’ The process of developing this label into an inner acceptance of herself as a woman—with the accompanying belief that it is good to be a woman—is complex. The outcome will depend in part on the convictions of the first caregiver with whom she identifies. It will also depend on the girl’s observations of how women are treated in the family and in the world at large and how women’s sexuality is understood. If women around her are socially stigmatized, despair and identity confusion may result. Where symptoms of PMS reflect such alienation, attention to these issues rooted in early family experiences may prevent the development of PMS.

Explicit discussion of different kinds of family roles may help women to examine their own family experiences and to reconsider their expectations of themselves. The behavior of each person may be defined by the roles he or she is assigned within a family system. Kinship roles define who is mother, father, daughter, son, sister, or brother. Stereotypical roles define who is nurturer, housekeeper, breadwinner, disciplinarian, and so on, and reflect society’s shared beliefs that are passed from generation to generation, constantly reinforcing the structure of a given culture. Unrealistic and irrational role expectations may define the good mother/bad mother, good father/ bad father, good teenager/rebellious teenager, and others, and are generated by unconscious conflicts and shared myths among the family members. To the extent that people can discuss roles and reach an understanding about how roles emerge, the likelihood of role strain diminishes. With this, the likelihood of the expression of role strain through physical symptoms may also decline.

3. Women’s Suffering in Relation to Contemporary Circumstances and the Effects of Culture

Prevention related to a woman’s contemporary circumstances includes clarification of cultural stereotypes and of implicit social attitudes about women. To the extent that stereotypes and attitudes are applied to women indiscriminantly and without reflection, they can negatively affect the psychological health of women. For example, if early experiences foster the cultural ideal of caretaking as womanly and good, this ideal carries the potential for promoting stereotypes of caring as womanly and a good woman as selfless and self-sacrificing. Thus, self-giving may not be assessed in terms of the intentions of the woman and the consequences of her behavior, but on the basis of whether or not her behavior is viewed as inherently feminine. In other words, the worth of the woman’s self-sacrifice may not be acknowledged and rewarded, but instead her behavior is viewed as nothing more than an indication of her fundamental feminine nature. As a result, a woman can believe that no effort she makes in her current situation is of significant value, leaving her feeling unappreciated and unhappy. Alternatively, if a woman insists on recognition for her contributions, is assertive, or expresses personal needs (e.g., through words, behaviors, and/or symptoms), her ‘‘request’’ may be disquieting for men, women, and institutions that equate femininity with self-sacrifice. Those who are threatened may retaliate against the woman rather than reward her. Such role conflicts may be especially likely to occur in cultures or subcultures that are rapidly changing and whose most vulnerable members (often women and children) may bear the brunt of such change.

Similarly, and more specifically, a society’s beliefs about menstruation can influence both expectations about the menstrual cycle and the reporting of symptoms. Women with PMS may be greeted with skepticism and invalidation by others because of the cultural taboos that surround menstruation. Moreover, when a woman’s complaints of PMS signal that she is not pregnant, her PMS symptoms can be interpreted from a cultural perspective as reproductive inadequacy or ‘‘deviance.’’ For these reasons, women may need support as they grapple with how their needs are responded to by others in confusing and negative ways because of cultural stereotypes. Over time, women may learn how to gear their expectations and behaviors so that they can remain true to themselves but also respect others’ views and seek appropriate affirmation.

B. Diagnosis

Each woman is unique in terms of her physical experience of menstrual cycle events, her cognitive interpretation of sensations related to menstruation, her conscious and unconscious emotional responses to her internal rhythms and timing, and her adaptive behaviors toward menstrual cycle events. When a woman expresses concern about her menstrual cycle or offers complaints suggestive of PMS, the health care provider must attend to the whole person and understand, from a developmental perspective, the complex social context in which the woman lives (Table IV). Such an approach is essential for making an accurate diagnosis of PMS and pursuing appropriate treatment interventions.

Table IV. Diagnostic Evaluation of Premenstrual Syndrome

General medical history

• Overall health

• Current medical and psychological issues

• Medications (prescribed and over-the-counter)

• Past medical and psychiatric history

• Habits (e.g., exercise, sleep, and eating patterns, smoking, alcohol, and drugs)

• Preventative health care (e.g., immunizations, cholesterol levels, pap smears, mammography)

• Developmental and social history

• Family illness history

• Sexual history (e.g., comfort with sexuality, current sexual functioning, past sexual experiences, high-risk behaviors)

Focused medical history

• Overall gynecological health

• Menstrual history (e.g., age at menarche, length of menstrual cycle, quantity and pattern of bleeding)

• Nature, timing, and severity of symptoms around menstruation

• Pattern of menstrual and premenstrual symptoms during adolescence and early adulthood

• Pattern of menstrual and premenstrual symptoms in relation to pregnancy, breast-feeding, and hormonal interventions (e.g., oral contraceptives)

• Unrecognized endocrine problems (e.g., thyroid dysfunction, androgen excess)

• Unrecognized psychiatric illness (e.g., depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, somatoform disorder)

Physical examination

• Mental status examination

• Screening physical examination, including examination for signs of

• endocrine dysfunction

• gynecologic illness

• overlooked health problems (e.g., anemia, infection)

• Screening laboratory tests (e.g., thyroid function tests)

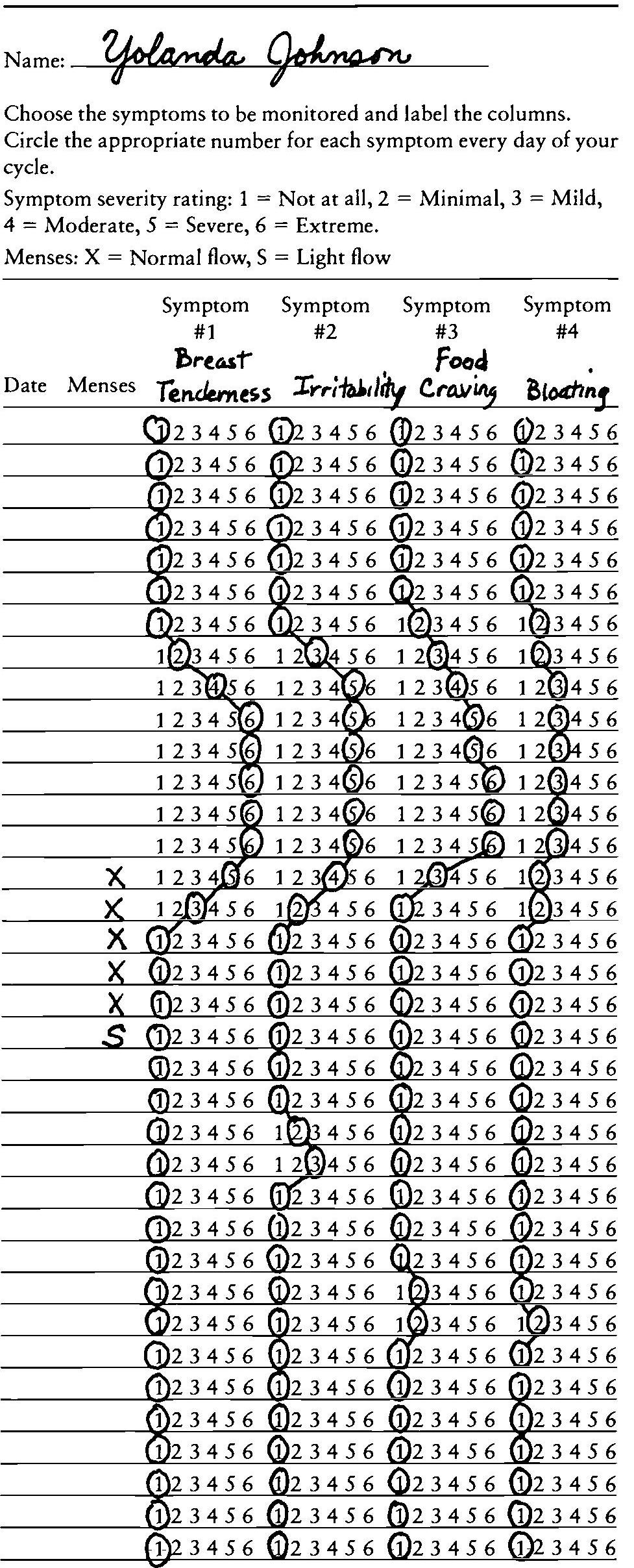

Prospective symptom rating:

Patient records the timing and severity of physical and psychological symptoms for at least two menstrual cycles. The pattern is evaluated during a subsequent appointment.

As there is no absolute independent, verifiable biological marker (such as a blood test) or physiobehavioral measure (such as increased nocturnal temperature or other signs related to individual circadian rhythms) to identify PMS reliably, the diagnosis of PMS is believed to be a clinical judgment. It is thought to be present when three criteria are met: (1) no other condition is present that accounts for the patient’s symptoms, (2) prospective daily symptom ratings demonstrate a marked change in severity of symptoms premenstrually for at least two menstrual cycles, and (3) there is a symptom-free week (usually Days 5 to 10) during the menstrual cycles. It is possible for a woman to have a psychiatric disorder or a physical disorder in addition to PMS as long as the symptoms of PMS are distinct from the other disorder and occur during the luteal phase and remit during menses.

Clinical investigation of PMS thus involves two kinds of information. First, it entails prospective documentation by the woman of symptoms and signs she experiences in clear association with phases of her menstrual cycle. Prospective daily ratings of symptoms with respect to quantity, quality, and severity for a minimum of 2 months are required to confirm a woman’s retrospective report of premenstrual symptomatology (Table V). A retrospective history of PMS is not sufficient for a diagnosis because it introduces biases, leading to an overdiagnosis of PMS. Second, other medical conditions that may account for the patient’s discomfort must be excluded. Clinicians must therefore perform a careful health history. A complete physical examination must also be conducted, including a mental status examination and a pelvic examination. Psychiatric conditions such as depression, anxiety, somatoform disorders, and others must be considered in the evaluation process. Gynecological conditions such as uterine fibroids, endometriosis, and fibrocystic breast disease, and other physical conditions such as anemia and endocrine dysfunction (e.g., diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, Cushing’s disease) must also be considered and appropriate diagnostic tests performed in the evaluation process. Coexistent medical and psychiatric disorders must be distinguished from disorders that might cause the patient’s symptoms and signs.

Table V. Daily Symptoms Calendar

C. Appropriate Treatment Interventions

Once a diagnosis has been established or refuted, results of the evaluation should be shared with the patient and various treatment strategies should be considered.

1. For Women Thought Not to Have PMS

Women with symptoms caused by another illness, but without demonstrable PMS, should receive reassurance and clarity about possible sources of their discomfort. Accurate information about sexual health, experiences normally associated with the menstrual cycle, and symptom patterns may be tremendously helpful. Treatment of a previously unrecognized or poorly controlled physical illness (e.g., hypothyroidism, diabetes mellitus) may eliminate the premenstrual complaints. New or more intensive treatment of a psychiatric disorder such as depression may lead to improvement in symptoms attributed to the premenstrual phase. Doses of psychotropic medication may need to be increased during the late luteal phase and early follicular phase to control symptoms. It should be made explicit that women who are thought not to have PMS will receive continued health care and will not be abandoned to cope with their symptoms alone.

Women whose evaluations do not yield clear evidence of PMS or of another physical or mental illness should be shown that their daily symptom ratings do not reflect a PMS pattern, that their physical examination and laboratory tests do not suggest another physical illness, and that their psychological evaluation has ruled out a mental disorder. Some time should be spent with women with these experiences to acknowledge the reality of their symptoms, even though the meaning of their symptoms is unclear. For example, these women could be in the incipient phases of developing PMS where their symptomatology is inconsistent or of too low a severity to qualify for the diagnosis of PMS. These women should be encouraged to continue charting their daily symptoms, to return in 3 to 6 months for reevaluation, and to ensure adequate sleep, proper diet, and healthy exercise. Alternatively, other sources of symptoms that are not disclosed early in the evaluative process, such as stressful life situations, can be explored and appropriate supports offered at this time.

2. For Women Diagnosed with PMS

Once PMS is documented, a wide variety of psychosocial and preventive health interventions should be considered. These treatments have not been demonstrated to be helpful to all women and their clinical scientific bases are not proven. Because the etiology of PMS is multifactorial and elusive, single pharmacologic interventions that ‘‘target’’ the causal mechanism of PMS have not been found. This fact should be reviewed carefully with each woman, and it should be understood that the goal of therapy is to find the unique approach that best addresses her specific needs and complaints.

- Providing women with accurate information about their sexual health, the menstrual cycle, and PMS in general is crucial in dispelling myths and addressing the sense of helplessness a woman may feel in relation to her symptoms. Explanation of symptoms and the natural history of PMS, descriptions of various treatment strategies with anticipated benefits, risks, side effects, and alternatives may prove to be immensely reassuring.

- The temporal pattern of their symptoms should be reviewed with women who experience PMS. Visualizing the type, severity, and timing of her symptoms can bring to the woman a sense of control over her symptoms sufficient enough to relieve distress. Women should be encouraged to develop ways of ‘‘planning ahead’’ for their premenstrual symptoms and signs so that they can prepare their families, close associates, and themselves for their symptomatic times. Efforts to limit external stress as much as possible (e.g., not assuming extra obligations or tasks at certain times) may help some women to navigate their monthly cycles more effectively.

- Consuming large amounts of caffeine or its equivalent (theophylline and theobromine, or methylxanthines) has been associated with women’s retrospective reports of more severe premenstrual symptoms. Because caffeine can cause irritability, insomnia, and gastrointestinal distress at any time of the month, it makes sense to limit the consumption of caffeine or related compounds throughout the month.

- Decreasing salt intake is commonly recommended as one way to minimize premenstrual bloating, although many women with this complaint do not actually gain weight premenstrually. As many women consume more salt than necessary and because some women do experience symptom relief from limiting their salt intake, it seems reasonable to recommend limiting salt intake at least prior to and during the usual symptomatic interval each month.

- Some researchers suggest that increased appetite and carbohydrate cravings have been linked to the need to increase sources of tryptophan for serotonin synthesis. A healthy diet of frequent meals including complex carbohydrates may relieve PMS symptoms and may be linked to the steady availability of tryptophan.

- Exercise has been shown to minimize some symptoms associated with fluid retention and to increase self-esteem. Except for women with obvious medical contraindications, women should be encouraged to participate all month in some kind of regular physical exercise. It is the frequency, not the intensity, of exercise that seems to make a difference.

If PMS symptoms persist after these measures have been tried, more rigorous pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions may be necessary.

One approach to pharmacologic treatment of PMS is to control the overall menstrual cycle. This approach entails hormonal intervention. Four principal strategies have been used:

- Oral contraceptives may minimize physical and psychological symptoms of PMS, as documented in both retrospective and prospective studies. Oral contraceptives may, however, also precipitate symptoms that resemble PMS, such as depression. In addition, risks and side effects of oral contraceptives include cardiovascular complications, migraine headaches, and increases in serum triglycerides. These considerations must be discussed and this strategy undertaken carefully.

- GnRH agonists and oophorectomy (i.e., surgical removal of ovaries) may effectively eliminate PMS symptoms, although this approach is associated with the unwanted effects of low estrogen production. Moreover, surgical risks must be balanced against the severity of PMS symptomatology to justify such an intervention. This strategy is best reserved for very debilitating PMS in older women, and only if less invasive methods have failed.

- Danazol is a synthetic androgen used to suppress the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis by inhibiting release of gonadotropin. It is superior to placebo when given daily, but many women cannot tolerate the side effects, which include weight gain and an imbalance of estrogen compounds and androgen (e.g., hirsutism, flushing, vaginitis).

- Estradiol implants have also been used successfully to treat PMS. The addition of synthetic progestin has been associated with a return of PMS symptoms but with significantly milder intensity than before hormonal treatment.

A second approach is to manage specific psychological symptoms. With respect to severe psychological symptoms, it is crucial first to verify that the woman, despite her discomfort, is sufficiently safe. A woman who is depressed to the point of being suicidal, or who is so angry that she might harm someone else, should be carefully protected. Four psychiatric medicines that address depression and anxiety have been used effectively in some patients with PMS: Xanax (benzodiazepine anxiolytic, GABA agonist), buspirone (anxiolytic, serotonin 1a agonist), nortryptiline (tricyclic antidepressant, noradrenergic and serotonergic agonist), and fluoxetine, sertraline, and others (antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors). These medications have both proven benefits and numerous side effects, and their use must be dictated by clinical judgment. For example, Xanax is a medication that addresses time-limited, target anxiety symptoms extremely well, but is sedating and highly addicting. Nortryptiline helps depressive symptoms effectively, but it may cause dry mouth, constipation, and sexual dysfunction. The serotonergic medications (e.g., Prozac, Zoloft) alleviate PMS symptoms (even in the absence of depression), but usually are taken daily and, while generally well-tolerated, may have unpleasant side effects (e.g., jitteriness, headaches, nausea). For these reasons, all medication choices must be approached carefully and monitored closely.

A third approach is to manage the predominantly physical symptoms of women with PMS. Here the interventions will depend on the medical issues and complaints. Diuretics can be helpful if patients have documented weight gain and evidence of fluid retention. Spironolactone has been a preferred diuretic medication because of its potassium-sparing properties. Other diuretics may be used so long as the possibility of hypokalemia is monitored. Vitamin E, bromocriptine (a dopamine agonist that can cause nausea), and tamoxifen (an oral nonsteroidal agent with antiestrogen properties that can cause headaches and fatigue) have all been shown to be beneficial for breast pain. Over-the-counter analgesics may be very valuable and safe in treating PMS-related headaches. In addition to good sleep routines for insomnia and healthy eating routines for food cravings, serotonergic antidepressants may be helpful for addressing fatigue and fostering stable eating patterns.

The choice of treatment should be grounded in the understanding of the woman’s needs in terms of which symptoms are most troublesome for her, which treatment interventions are likely to be most effective for these symptoms, and which treatment strategies will be most acceptable to the patient according to her values and way of life.

Bibliography:

- Barbieri, R. L. (1993). Physiology of the normal menstrual cycle. In I. Smith & S. Smith (Eds.), Modern management of premenstrual syndrome (Ch. 4). New York: Norton Medical Books.

- Ferin, M., Jewelewicz, R., & Warren, M. (1993). The menstrual cycle: Physiology, reproductive disorders, and infertility. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Frank, R. T. (1931). The hormonal basis of premenstrual tension. Arch. Neurol. Psychiatry 26, 1053–1057.

- Gold, J. H., & Severino, S. K. (Eds.). (1994). Premenstrual dysphorias: Myths and realities. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

- Golub, S. (1992). Periods: From menarche to menopause. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Jensvold, M. F. (1992). Psychiatric aspects of the menstrual cycle. In D. E. Steward & N. L. Stotland (Eds.), Psychological aspects of women’s health care: The interface between psychiatry and obstetrics and gynecology. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

- Severino, S. K., & Moline, M. L. (1989). Premenstrual syndrome: A clinician’s guide. New York: Guilford.

- Stewart, F., Guest, F., Stewart, G., & Hatcher, R. (1987). Understanding your body: Every woman’s guide to gynecology and health. New York: Bantam.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.