This sample Prevention of Academic Failure Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

Prevention of academic failure is a serious challenge because children who fail academically experience significant social and economic challenges throughout their lives. Causes of academic failure include familial, socioeconomic, and cultural issues that lead to a lack of readiness for school, academic, instructional, and motivational problems as well as physiological, cognitive, and neurological barriers to learning. Attempts to help students who are experiencing academic failure fall into three categories: prevention, intervention, and remediation. Preventive approaches aim to stop academic failure before it occurs. Early intervention programs aim to catch children during key developmental periods and facilitate development and readiness skills. Remediation programs are usually applied when students have demonstrated significant skill deficits and are experiencing significant academic failure. Special education programs often take this form, as do other kinds of academic accommodations for students identified with special needs.

Outline

- Defining Academic Failure

- Causes of Academic Failure

- Preventing Early School Failure

- Preventing Failure in the Intermediate Grades and Middle School

- Preventing Academic Failure in High School

- Conclusion

1. Defining Academic Failure

A lot depends on children’s success in school—their self-esteem, their sense of identity, their future employability. Preventing academic failure means that we, as a society, are much more likely to produce individuals who feel confident about their ability to contribute to the common good, whose literacy skills are competent, and who are able to hold jobs successfully. Thus, prevention of academic failure should be a primary concern for any society. But exactly what is meant by academic failure? What does the term connote? Generations of schoolchildren since the 1920s, when the system of grade progression began, have equated academic failure with retention in grade. School failure meant literally failing to progress onto the next grade, with the assumption that the skills and knowledge taught in that grade had not been mastered. To have flunked multiple grades quickly led to quitting school altogether—the ultimate academic failure.

More recently, academic failure has come to mean a failure to acquire the basic skills of literacy. Students who were unable to read at a functional level, to communicate effectively through writing, and to complete basic math calculations were seen as representing a failure of the academic system even though they might hold high school diplomas. The practice of moving students on from one grade to the next even though they might not have mastered basic competencies associated with lower grade levels is often referred to as social promotion. This type of academic failure led to calls for an increased emphasis on basic skills, that is, the ‘‘three R’s’’—reading, (w)riting, and (a)rithmetic—in public education. Partly in reaction to emphasis on basic skills, a third interpretation of academic failure has also emerged. In this view, academic failure occurs not only when students fail to master basic skills but also when they emerge from school without the ability to think critically, problem solve, learn independently, and work collaboratively with others—a skill set deemed necessary for success in a digital age. This underachievement symbolizes a significant loss of intellectual capital for a culture. Finally, statistics show that students who do not complete high school are much more likely to need welfare support, have difficulties with the law and police, and struggle economically and socially throughout their lives. Thus, academic failure ultimately means both the failure to acquire the skill sets expected to be learned and the failure to acquire official documentation of achievement by the school system.

2. Causes Of Academic Failure

Students struggle academically for many reasons, including familial, socioeconomic, and cultural issues that lead to a lack of readiness for school, academic, instructional, and motivational problems as well as physiological, cognitive, and neurological barriers to learning. Early school failure often occurs because children enter the structured school environment not ready to learn.

2.1. School Readiness

School readiness refers to the idea that children need a certain set of skills to learn and work successfully in school. Often this term refers to whether or not children have reached the necessary emotional, behavioral, and cognitive maturity to start school in addition to how well they would adapt to the classroom environment. To create some consensus about when a child should begin school, states designate a specific cutoff date. If a child reaches a certain age by the cutoff (usually 5 years for kindergarten and 6 years for first grade), the child may begin school. However, cutoff dates are arbitrary and vary considerably across nations, and age is not the best determinant or most accurate measure of whether or not a child is ready to begin school. Research has suggested that we must look at all aspects of children’s lives— their cognitive, social, emotional, and motor development—to get an accurate idea of their readiness to enter school. Most important, children’s readiness for school is affected by their early home, parental, and preschool experiences.

Stated in its simplest form, school readiness means that a child is ready to enter a social environment that is focused primarily on education. The following list of behaviors and characteristics are often associated with school readiness:

- Ability to follow structured daily routines

- Ability to dress independently

- Ability to work independently with supervision

- Ability to listen and pay attention to what someone else is saying

- Ability to get along with and cooperate with other children

- Ability to play with other children

- Ability to follow simple rules

- Ability to work with puzzles, scissors, coloring, paints, and the like

- Ability to write own name or to acquire the skill with instruction

- Ability to count or acquire skills with instruction

- Ability to recite the alphabet

- Ability to identify both shapes and colors

- Ability to identify sound units in words and to recognize rhyme

Family environment is very important in shaping children’s early development. Some family factors that can influence school readiness include low family economic risk (poor readiness for school is associated with poverty), stable family structure (children from stable two-parent homes tend to have stronger school readiness than do children from one-parent homes and from homes where caregivers change frequently), and enriched home environment (children from homes where parents talk with their children, engage them in conversation, read to them, and engage in forms of discipline such as ‘‘time-out’’ that encourage self-discipline have stronger readiness skills).

Children’s readiness to read, in particular, has gained greater attention from educators recently as the developmental precursors to reading have become more evident. During the preschool years, children develop emerging literacy skills—preacademic skills that allow children to develop a disposition to read, write, and compute. Children are ready to read when they have developed an ear for the way in which words sound and can identify rhyme and alliteration, blend sounds, recognize onset rime (initial sounds), and identify sound units in words. Together, these skills are called phonological awareness and usually emerge in children between 2 and 6 years of age. Children with good phonological awareness skills usually learn to read quickly. Children who are poor readers have weak phonological skills, and children who do not learn to read fail in school. Another important readiness skill that helps children to learn to read is called print awareness. Print awareness means that children are capable of the following:

- Knowing the difference between pictures and print

- Recognizing environmental print (e.g., stop signs, McDonald’s, Kmart)

- Understanding that print can appear alone or with pictures

- Recognizing that print occurs in different media (e.g., pencil, crayon, ink)

- Recognizing that print occurs on different surfaces (e.g., paper, computer screen, billboard)

- Understanding that words are read right to left

- Understanding that the lines of text are read from top to bottom

- Understanding the function of white space between words

- Understanding that the print corresponds to speech word for word

- Knowing the difference between letters and words

Children also need to learn book-handling skills such as orienting a book correctly and recognizing the beginning and the end of a book. Children who begin school without these basic readiness skills are at risk for school failure. The use of screening assessments during preschool and kindergarten to identify students who may be at risk for academic failure, particularly in the area of phonemic awareness, has been shown to be a sound method of predicting which children will have difficulty in learning to read. Most likely to be retained in kindergarten are children who are chronologically young for their grade, developmentally delayed, and/or living in poverty.

2.2. Academic, Instructional, and Motivational Reasons

Children who do not master basic reading skills, specifically the ability to automatically decode new words and build a sight word vocabulary that leads to fluency, experience academic failure. By third grade, learning to read has become reading to learn. In other words, in third grade the curriculum becomes focused much less on teaching students to acquire the basic tools of literacy (reading, writing, and computing) and much more on using those tools to learn content, express ideas, and solve problems. At this point, students are likely to be given content textbooks in science and social studies and to read nonfiction for the purpose of gaining new information. Thus, the inability to read effectively and to learn to study independently often leads to failure at the elementary and middle school levels and also creates profound motivation problems at the high school level that contribute to the ultimate school failure—dropping out. The inability to master key concepts in pivotal classes such as algebra, now typically taken at the middle or junior high school level, often limits students’ ability to proceed in coursework. Students may fail to understand algebraic concepts due to their developmental level. (Many students are stilling thinking in concrete terms in middle school and have not yet moved into a stage of cognitive thinking allowing them to understand formal logic and manipulate symbols—a developmental source of failure.) In addition, some students might not have automatized basic arithmetic skills, particularly computing with fractions—an academic or instructional failure. Some students may have become turned off to math and accepted self-images that permit poor math skills— a motivational failure. Finally, many students will fail algebra for all of these reasons, and the impact will often be that they will finish school in a nonacademic or basic track or might even drop out.

Thus, academic and instructional reasons for school failure include the effectiveness of the instruction a student has received and the quality of remediation strategies or programs available. The following is a typical example that illustrates academic and instructional reasons for school failure. A teacher reports that a student is having difficulty in getting beyond the primer level in reading and is being considered for retention. The child was assessed as having average intelligence. No behavioral or attention problems were noted. Closer inspections of the student’s reading skills indicated that she had poor phonological skills and was not profiting from the type of classroom reading instruction she was receiving that depended heavily on auditory phonics instruction stressing ‘‘sounding out words’’ and matching sound–symbol connections. Appropriate interventions included using techniques to build up a sight word vocabulary through repetition and distributed learning and introducing the student to a visual decoding system to provide her with a method for reading unknown words by analyzing the words and breaking them down into more familiar visual units.

2.3. Physiological, Neurological, and Cognitive Reasons

Imagine a child spending most of the year in kindergarten with an undetected hearing loss that has made it very difficult for her to benefit from instruction. Imagine another child in first grade struggling to learn because her vision impairment has not been caught or corrected. Similarly, students suffering from a variety of conditions and illnesses, such as childhood diabetes, asthma and allergy-related problems, and sickle cell anemia, may have difficulty in maintaining energy and attention in school due to chronic fatigue and the impact of medications. Children may also suffer from orthopedic or motor impairments that make it difficult for them to explore their environment, interact with others, and/or master tasks that demand motor skills.

Students who suffer from various kinds of neurological disorders or learning disabilities may also have cognitive learning problems that make it difficult for their brains to process information, interpret sounds and symbols efficiently in reading, calculate and understand number concepts, and/or write effectively. Other children may have cognitive deficits, such as mental retardation, that limit their ability to absorb and apply regular classroom instruction. Children with attention deficit disorders have difficulty in directing and maintaining their attention, may exhibit impulsive behavior, and have trouble in interacting independently in typical classroom environments without support. Specialized and/or special education interventions are designed to provide individualized strategies and approaches for students who have physiological-based learning problems interfering with their ability to learn.

3. Preventing Early School Failure

3.1. Early Intervention Programs

Programmatic interventions may include developing screening programs to identify children at risk for school failure and to ensure early access to readiness programs already available in the school or community such as Head Start. Many states are now developing guidelines for children age 6 years or under based on the National Association for the Education of Young Children’s (NAEYC) list of developmentally appropriate practices. The major challenge facing early intervention programs is to provide developmentally and individually appropriate learning environments for all children. Essential ingredients to successful preschool experiences include small group and individualized teacher-directed activities as well as child-initiated activities. Quality programs recognize the importance of play and view teachers as facilitators of learning.

3.2. Preventing School Failure in the Elementary Grades

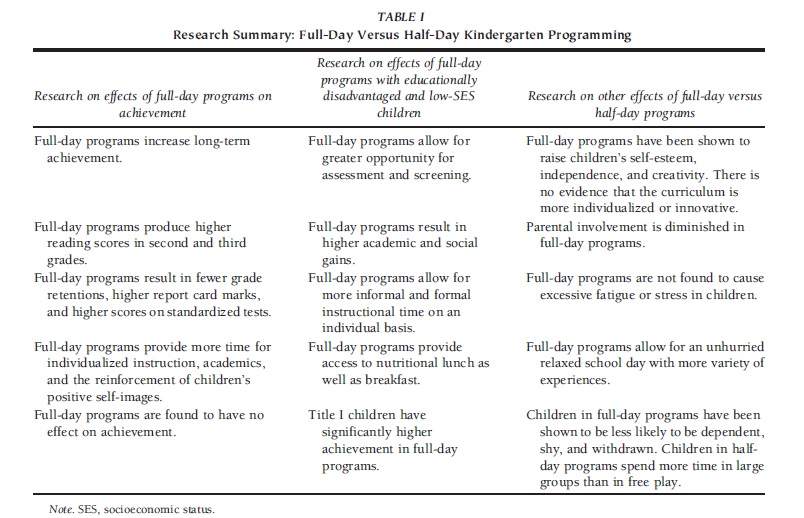

Full day kindergarten (as opposed to half day) programs provide more time for field trips, activity centers, projects, and free play. At-risk students who attend rigorous yet nurturing full day programs have a greater chance of experiencing academic success. Full day kindergarten programs help increase academic achievement as well as decrease the number of children retained in the early elementary grades. Research shows that full day kindergarten programs for children who come from disadvantaged backgrounds lead to stronger achievement in basic skill areas and generally better preparation for first grade.

Table I summarizes the research on full-day kindergarten. Any decisions about whether or not to schedule full or half-day programs should recognize that what a child is doing during the kindergarten day is more important than the length of the school day.

The instructional technology that enables classroom teachers to meet the needs of students of different skill levels is already available, but in many cases teachers do not have access to that technology. Reading interventions that provide intensive, early, and individualized help that targets a child’s specific weaknesses (e.g., Success for All, Reading Recovery, Direct Instruction) have been shown to be effective in reducing early reading failure. Instructional approaches such as mastery learning, adaptive education, team teaching, cooperative learning, peer tutoring, and curriculum-based assessment are methods that have been shown to produce academic gains in students of all achievement levels in the elementary grades. Recently, technology has offered greater individualization of instruction and increased flexibility in allowing students to progress at their own pace and to respond to instruction.

TABLE I Research Summary: Full-Day Versus Half-Day Kindergarten Programming

TABLE I Research Summary: Full-Day Versus Half-Day Kindergarten Programming

4. Preventing Failure In The Intermediate Grades And Middle School

Remedial programs, such as the Title I programs, have also been used to remediate early skill deficits in reading and math. However, developing intervention programs, such as after-school tutoring and summer school courses, might not be sufficient to make up serious deficits in short amounts of time and cannot take the place of preventive systemic approaches. The use of learning strategies instruction has been shown to be very effective in improving study skills and performance in middle school students. Because unsuccessful middle school students often lack basic strategic learning skills, intervention programs should also target these areas. Similarly, approaches that use learning, problem-solving, and memory strategies are the most effective interventions in terms of producing actual gains in student achievement in the classroom.

5. Preventing Academic Failure In High School

At the secondary level, development of reentry programs for dropouts and alternative education programs, such as those that combine teaching skills with job training, are essential to prevent further academic failure. Research on academic failure at the secondary level has generally examined the relationships between grade retention and attendance, suspension, and self-concept, with an emphasis on the correlation between retention and dropout rates. Academic failure at the high school level is related to attendance and suspension rates. In general, students who are failing do not attend school on a regular basis. In addition, students who have been retained prior to the secondary level are less likely to attend school on a regular basis in junior and senior high school. Furthermore, regardless of the grade in which retention occurs, secondary students who have been retained often exhibit low self-esteem.

Many studies have reported that students who drop out are five times more likely to have repeated a grade than are students who eventually graduate. Being retained twice virtually guarantees that a student will drop out of school, and grade retention alone has been identified as the single most powerful predictor of dropping out. The dropout rate of overage students is appreciably higher than the dropout rate of regularly promoted students when reading achievement scores are equivalent for the two groups. Even in high socioeconomic school districts, where students are less likely to leave school, a significant increase in dropout rates has been found for retained students.

Successful programs at the high school level often have two characteristics: (a) one or more individuals who develop relationships with students individually and monitor their progress carefully and (b) some mechanism to allow students who have failed courses and lost credits to regain these credits in quicker than normal time, allowing for graduation at the expected time. Simply put, successful programs must address the motivational issues that have developed by adolescence and the lack of academic achievement identity typically present in students who drop out of school. School to-work programs that combine vocational counseling with on-the-job experience are successful ways in which to increase a sense of academic competence while connecting to students’ current self-concepts and needs.

6. Conclusion

Attempts to help students who are experiencing academic failure fall into three categories: prevention, intervention, and remediation. Preventive approaches aim to stop academic failure before it occurs. Early intervention programs from birth to 5 years of age, for example, aim to catch children during key developmental periods and facilitate development and readiness skills. Intervention programs, such as Robert Slavin’s Success for All program, aim to intervene as soon as students begin to show signs of slipping behind their peers. Intervention plans may also be designed under Section 504 of the Americans with Disabilities Act, which mandates accommodations in the instructional environment for students who have physical or neurological problems that may interfere with their ability to learn or succeed in a typical classroom. Remediation programs are usually applied when students have demonstrated significant skill deficits and are experiencing significant academic failure. Special education programs often take this form, as do other kinds of academic accommodations for students identified with special needs.

Of course, early identification and prevention of academic problems is always preferable to later intervention and remediation. Thus, systemic solutions that target early reading deficits, independent learning skills, and motivational problems from a developmental perspective are essential to the prevention of academic failure. Working to change school practices will require sharing the research with educators, conducting evaluations on the outcomes of alternative interventions at the local level, and lobbying at the state level to promote changes in policy and to advocate for alternative service delivery systems that more effectively meet the needs of students experiencing school failure. Successful programs to boost student achievement, however, must attack underachievement in three key areas. These key areas—early reading intervention, acquisition of strategic learning and study skills, and motivation to achieve—are highly related to school failure.

First, acquisition of basic reading skills must be addressed. If students underachieve in the primary grades, it is most often because they have failed to learn to read. Kindergarten screenings should include an assessment of phonological awareness. Children identified with weak skills should be targeted for intervention through phonological awareness training in kindergarten. Prekindergarten programs for high-risk students are recommended. Students should be tracked using curriculum-based assessments of oral reading in the primary grades. Any student who falls behind the average rate of acquisition for his or her class should receive an individualized analysis of reading skill and additional after-school intervention based on that analysis to allow the student to ‘‘catch up’’ to classmates. This early, intensive, and individualized intervention allows for all students to enter the intermediate grades as able readers. Some students with special needs might not progress at the same rate as their classmates, but they too will benefit from early reading interventions.

Second, students must acquire independent learning and study skills during the intermediate and middle school years if they are to maximize achievement and be competitive in the job market of tomorrow. Many students underachieve in middle school because they lack the organizational and learning strategies to master the demands of the upper grades. Embedded approaches to strategy instruction facilitate generalization and encourage students to use all of their mental tools. Assessment of students’ study skills and metacognitive development (i.e., the degree to which they are aware of and control their own cognitive processes) leads directly to specific interventions.

Third, students in high school often underachieve because they lack the motivation to excel academically. They often have failed to incorporate pictures of themselves as successful students into their self-concepts. Through a variety of approaches, including staff in service, a study skills coach approach to peer tutoring, and an individualized profile of each student’s study style and vocational options, increased academic competence and a value for academic work can be built.

References:

- Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (1999). How people learn. Washington, DC: National Academy of the Sciences Press.

- Elicker, (2000). Full day kindergarten: Exploring the research. Bloomington, IN: Phi Delta Kappa International. Gredler, G. (1992). School readiness: Assessment and educational issues. Brandon, VT: CPPC Publishing.

- Jimerson, S. R. (1999). On the failure of failure: Examining the association between early grade retention and education and employment outcomes during late adolescence. Journal of School Psychology, 37, 243–272.

- Minke, K. M., & Bear, G. G. (Eds.). (2000). Preventing school problems, promoting school success: Strategies and programs that work. Silver Spring, MD: National Association of School Psychologists.

- National Institute of Child Health and Development. (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel: Report of the subgroups. Bethesda, MD: Author.

- Slavin, R. E., Karweit, N. L., & Madden, N. A. (1989). Effective programs for students at risk. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

- Smith, L., & Shepard, L. A. (Eds.). (1989). Flunking grades: Research and policies on retention. New York: Falmer.

- Springfield, S., & Land, D. (Eds.). (2002). Educating at-risk students. Chicago: National Survey of Student Engagement. (Distributed by University of Chicago Press).

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.