This sample Psychopathology Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of psychology research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

The definition of psychopathology has long been a matter of theoretical and practical importance to individuals involved in the mental health movement. It is primarily psychiatric and psychological professionals who have been involved in the conceptualization and definition of psychopathology. At the theoretical level, debates have centered around such issues as whether humans or their behavior is disordered or “ill,” the different approaches that can be taken to define health and pathology, and the moral implications of defining some individuals as having a pathological condition. At the practical level, there have been extensive discussions about how best to conceptualize and assess abnormal behavior, and how to minimize the potentially negative influences of labeling.

Outline

I. Definitional Issues

A. Normalcy versus Abnormalcy

B. Conceptual Approaches to Psychopathology

II. Categorical Models of Psychopathology

A. Historical Precursors to the Diagnosis of Psychopathology

B. The International Classification of Diseases

C. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

D. Future Issues and Developments

III. Dimensional Models of Psychopathology

A. Trait versus Symptom Approaches

B. Models of Psychopathology

IV. Future Issues in Psychopathology

A. Categorical and Dimensional Approaches

B. Theories of Psychopathology

I. Definitional Issues

A. Normalcy versus Abnormalcy

Within the overall frame of reference of psychopathology a number of related concepts must be defined and distinguished. As a term, psychopathology refers to an aberrant or dysfunctional (i.e., pathological) way of functioning, where functioning is defined in terms of behavioral, interpersonal, emotional, cognitive, and psychophysiological patterns. Whether a particular way of functioning is aberrant can be judged by a number of criteria. Included in such criteria is whether that functioning causes personal distress, causes others in the person’s social sphere to become distressed, falls outside of accepted social norms or values for functioning, falls within certain criteria for abnormal functioning, or is a statistically rare functional pattern. Each of these approaches to establishing an aberrant pattern of functioning has advantages and disadvantages. It is due to the presence of these approaches that different approaches to conceptualizing psychopathology exist.

Mental illness is a term that is largely synonymous with psychopathology, although it carries the implication that the unusual or aberrant patterns of functioning seen in these conditions reflect some form of disease or illness. The medical model reflected in the illness term is rejected by some psychopathologists, as an inappropriate model for either all or some forms of psychopathology. Another term that is considered synonymous with psychopathology is abnormal behavior. This term is equally descriptive as psychopathology, as neither implies a belief in the cause of the unusual or aberrant patterns of functioning, but is more focused on the behavioral component of the dysfunction.

A term that is sometimes confused with psychopathology is insanity. Although such terms as insane, mad, and lunatic were once used in much the same way modern society uses the terms psychopathology and mental illness, insanity has taken on a much more narrow definition. Specifically, insanity is a legal term that addresses the question of whether a particular person can be held criminally responsible for his or her actions. Several different tests of insanity exist, but in every case the decision as to whether a person is legally insane is made by a judge or jury, and is made with respect to the crime they are alleged to have committed. It is the case that many different forms of abnormal or psychopathological behavior do not meet the criterion for insanity. Further, it is possible that a person can be legally insane (i.e., not legally responsible for their actions) when they have no discernable form of psychopathology, as defined by mental health practitioners.

A term that has relevance to psychopathology is mental health. While one can imagine mental health as the absence of psychopathology, it is also possible to conceptualize mental health in terms of its positive attributes. The World Health Organization has defined mental health as “inner experience linked to interpersonal group experience,” and is associated with such characteristics as subjective well-being, optimal development and use of mental abilities, social adaptation, and achievement of goals.

In summary, psychopathology is a concept that is similar to mental illness and abnormal behavior, but is distinct from insanity. Mental health can be conceptualized as the absence of psychopathology, but also has other positive components not related to the concept of psychopathology.

B. Conceptual Approaches to Psychopathology

There are a large number of theoretical approaches to psychopathology, and these have steadily evolved over the centuries.

One dominant belief about the cause of abnormal behavior is that of possession; which is the idea that evil spirits or demons possess the mind and body of the person in question and cause them to behave in an aberrant fashion. There is fossil evidence that early humans believed in demonic possession as a cause of abnormal behavior, as there are skulls dating from prehistoric times which show purposeful cutting of the skull, or trephination. Trephination is often explained as an effort to release pressure in the skull, which may have been conceptualized by early humans as possession by an evil spirit. The idea of demonic possession as an explanation for abnormal behavior continues to persist (for example, the Roman Catholic Church still has procedures for exorcism as part of its accepted canon, and voodoo is still practiced in some parts of the world today), but it has largely been supplanted by other explanations of abnormalcy.

One early alternative model to possession was the humoral theory promoted by Hippocrates. The humoral model proposed that four humors, or fluids, are in the body, and that each is associated with a particular attitude and time of life. Blood, for example, is associated with growth, optimism, and good health, while black bile, or melancholia, is associated with death, depression, and darkness. The humoral theory was a prominent one in medicine for centuries, but has been since shown to be false.

Contemporary conceptions of psychopathology can be broken down into the two major categories of categorical and dimensional types. Categorical conceptions of psychopathology view abnormal behavior as discontinuous with normal behavior; as something that has a qualitatively different sense to it. Such conceptions are apt to include ideas of illness or disease processes, as these processes are those that distinguish normal from abnormal functioning. Categorical approaches to psychopathology are consistent with the practice of diagnosing or labeling dysfunctional patterns of functioning. The categorical approach to psychopathology is very heavily subscribed to because diagnosis is often considered to be necessary prior to the provision of treatment in psychiatric settings.

Dimensional approaches to psychopathology view aberrant functioning as falling on a continuum, with some types or levels of functioning being more or less dysfunctional than others. Within a dimensional approach diagnosis and labeling are less accepted, except to the extent that labels are applied to individuals at agreed upon points along a continuum. For example, if a person bites his or her nails more than three times a week, we might label that as “abnormal”; less than three times a week might be considered “normal.” Dimensional approaches are often used in combination with statistical conceptions of what is “average” or normal, and abnormalcy is defined as being atypical or highly different from the “average” person.

II. Categorical Models of Psychopathology

A. Historical Precursors to the Diagnosis of Psychopathology

The labeling of abnormal behavior has taken place for centuries. In ancient Greek society, such disorders as melancholia (what we would today term depression), mania (agitated or excited behavior), and phrenitis (most other forms of psychopathology, including severe forms of thought and behavior dysfunction) were distinguished. Models for the onset (etiology) of these disorders were established, and these disorders had differentiated treatment programs.

After the Dark Ages, the Renaissance and Enlightenment periods of Western civilization saw a renewed and more sophisticated approach to the diagnosis of psychopathology emerge. With the creation of asylums, large institutions designed for the holding and treatment of persons with mental illness, came the ability to study, differentiate, and more carefully assess abnormal conditions. Different systems for diagnosing psychopathology began to emerge, with different labels being proposed, debated, and either accepted or rejected. By the end of the 19th century, the number of divergent systems for diagnosis was recognized as a serious problem for the credibility and acceptability of any diagnostic system.

The approach to diagnosis and labeling that has been generally accepted was formalized by a German physician, Emil Kraepelin, in 1883. Using an approach comparable to that used in the rest of medicine, his approach included the assessment of different symptoms that formed cohesive patterns called syndromes. These syndromes, once identified, could then be labeled. In the original Kraepelinian diagnostic system there were a relatively small number of syndromes and diagnoses, but each was conceptually distinct and had its own specific symptoms.

B. The International Classification of Diseases

The World Health Organization (WHO) adopted Kraepelin’s system for diagnosing psychopathology, and has listed mental disorders as potential causes of death since 1939. The list of mental disorders included in the WHO directory has been revised a number of times, and the 1969 revision in particular received some acceptance. In 1979 the WHO published the ninth revision and the current version of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD ). There are a total of 30 major categories of mental disorders in the ICD-9. As many of these categories contain more specific forms of psychopathology, there are a total of 563 diagnostic categories in the ICD-9.

One of the principle features of the ICD is that it distinguishes organic from nonorganic forms and causes of abnormal behavior. For example, a major distinction is made between “organic psychotic conditions” and “other psychoses.” This distinction has been severely examined in the diagnostic literature as potentially lacking validity. For example, it is sometimes the case that what appears to be the same type of abnormal behavior may have different etiological bases; it is often impossible, however, to know with certainty which of the different etiological possibilities is the correct one. A diagnostic system that requires the diagnostician to make etiological judgments may therefore force false decisions.

Another aspect of the ICD is that it distinguishes “psychotic” from “nonpsychotic” (also referred to as “neurotic”) conditions. The psychotic-neurotic distinction within the ICD is also problematic. For example, depressive conditions are found listed both as psychotic (major depressive disorder) and neurotic (depressive disorder) conditions, but the distinction between these two hypothetically distinct types of depression is not clear.

Despite some problems with the ICD system for diagnosing mental disorder, it is a widely subscribed to international model for diagnosis. It is the dominant approach used in Europe, as well as countries that have been under European influence. The World Health Organization is currently at work on the ICD-10.

C. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

Due to problems with earlier versions of the ICD, the American Psychiatric Association developed its own system for diagnosis. Referred to as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), the system was first published in 1952, and has since been updated and republished three more times. The current DSM is the fourth version, which was published in 1994).

The first two editions of the DSM had many similarities to the ICD. Distinctions were made between psychotic and nonpsychotic disorders, for example, and the diagnostic system included many etiological terms in the diagnoses. In 1980, with the publication of DSM-III, the American Psychiatric Association made a major departure from this approach and deleted, as much as possible, all references to putative causes of disorder. Instead, the DSM became a more descriptive system that attempted to label disorders solely on their objective features, with as little inference as possible about the cause of the disorders.

In addition to the more descriptive nature of the later editions of DSM, an additional feature was that it was multi-axial. The multi-axial nature of the DSM-IV meant that it examined different axes or dimensions of functioning within the person being diagnosed at a single time, in order to achieve a more rounded assessment of the person and their functioning.

DSM-IV has continued the basic descriptive approach of the DSM-III. The DSM-IV, as was true for the DSM-III, has five major axes. The first two axes are those most analogous to the ICD diagnostic system. Axis I comprises the major psychopathology diagnoses, while Axis II is used to diagnose personality disorders and mental retardation. Axis Ill is used to diagnose physical disorders and conditions. Some of these disorders or conditions may be relevant to the other psychopathology diagnoses, whereas other medical disorders or conditions may simply help to round out a picture of the person’s current problems. Axis IV of the DSM-IV is used to rate the severity of psychosocial stressors, whereas Axis V consists of a global assessment rating of the individual’s functioning for the past year.

In order to diagnose a person using the DSM-IV, information should be provided on each of the five axes. Thus, whereas only Axes I and II are comparable to the ICD’s diagnostic labels, the DSM system is more comprehensive than the ICD, and provides more of a complete context in terms of the patient’s medical and psychosocial issues.

D. Future Issues and Developments

A large number of conceptual, research, and ethical issues are relevant to the categorical approaches to psychopathology. At the conceptual level, issues of validity (i.e., accurate portrayal of reality) have been raised. These issues have taken a number of forms. For example, the fact that over time the total number of diagnostic categories has been increasing, and the fact that the ICD and the DSM systems have different numbers and types of diagnoses, leads to the question about which (if either) system best reflects the real range of psychopathology. Ideally, diagnostic systems should be both comprehensive (that is, include all potential diagnoses) and distinctive (that is, each diagnostic category should be distinct and minimally overlapping with other categories). It is not clear at present that either existing system meets these criteria. Nor is it easy to imagine how they could demonstrate that they are both comprehensive and distinctive.

Another validity issue that has been raised with regard to the two major diagnostic systems is the extent to which a categorical system best represents psychopathology. This issue has been particularly raised in the case of the personality disorders, where it has been argued that rather than being discrete disorders they represent the extreme ends of personality dimensions. According to this view, rather than diagnosing personality disorders such as dependent personality disorder, psychopathologists should speak about the relative strength or weakness of certain personality dimensions such as dependency.

Although the issue of whether disorders are dimensional or categorical in nature is most acute in the case of personality disorders, it is also clear that in other disorders judgments must be made about when a given behavioral pattern or other symptom falls outside the range of normal. Consider, for example, the diagnosis of anorexia nervosa. Within that diagnosis are a number of judgments that a diagnostician would have to make, including what is an “expected body weight,” when a fear of being overweight is “intense” and when thoughts about body size are “disturbed.” While at the extremes of such judgments there would likely be high agreement across diagnosticians, less extreme fears and disturbances are more difficult to judge with certainty. Put otherwise, some of the symptoms are themselves not dichotomous, but reflect dimensions of disturbance, which are identified only if they cross some imaginal “line” of dysfunction. Decisions about how to recognize where that line has been crossed require some agreement among diagnosticians about what that line is, and how to recognize it is being breached.

Similar arguments have been made with respect to most forms of childhood disorders, as these disorders are typically conceptualized in terms of extreme forms of behavior (for example, too much aggressive behavior) that might better be seen as extremes on a continuum rather than discrete forms of psychopathology.

A third issue about diagnoses has been that to some extent they do not reflect the real world of psychopathology, but rather society’s beliefs about and experience of abnormal behavior. Critics of diagnosis have pointed out that the “emergence” of new disorders and deletion of others reflect changing societal values, rather than scientific advances that could validate such changes. For example, the diagnosis of homosexuality has had an interesting history within the DSM system. In the DSM-II, published in 1968, homosexuality was defined as a psychopathology diagnosis. By the time DSM-III was published in 1980 the system had changed, such that only ego-dystonic homosexuality (i.e., sexual preference for a same-sex person, but where the individual felt that this preference was inconsistent with their own wishes) was a recognized disorder; instances where the homosexual patterns were ego-syntonic (consistent with the persons’s wishes) were not considered abnormal. Homosexuality has been totally deleted as a diagnostic label in the DSM-IV (ICD continues to include homosexuality). It has been pointed out that this evolution of approaches to homosexuality mirrors a growing recognition and acceptance of homosexuality in Western society. It has been argued, therefore, that the changing diagnoses related to homosexuality do not reflect changes in the scientific basis of that diagnosis, but rather reflect changes in the attitudes and biases that the developers of diagnostic systems share with society at large. It has been similarly argued that other disorders, such as anorexia nervosa, reflect societal beliefs and awareness about specific behaviors, rather than necessarily reflecting the “true” nature of psychopathology.

At the scientific level, the major issues that face categorical systems of psychopathology are those related to the internal consistency and reliability of diagnostic categories. If a perfect diagnostic system existed, then every person with psychopathology should be captured in the system, and every trained diagnostician should recognize an individual’s unique diagnoses in a manner consistent with other diagnosticians. Research on these issues suggests that our current systems, although better than their precursors, do not closely approximate these goals. Clearly, further research and development are needed to clarify why consistency and reliability have been elusive.

Finally, there have been ethical arguments raised against the practice of diagnosis. It has been argued, for example, that diagnosis involves an artificial process of labeling people, and that once these labels are applied they become more than descriptions of the individual’s current functioning, but become long-term crosses for the individual to bear. These abuses of the diagnostic process have been used as a basis for arguing that the utility of diagnosis is more than offset by its costs, and should be abandoned.

III. Dimensional Models of Psychopathology

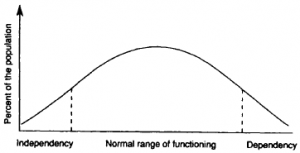

Dimensional models view psychopathology as deriving from underlying dimensional constructs that explain both normal and abnormal functioning. For example, it is possible to imagine a construct called interpersonal dependency. At one end of this construct is extreme dependency, as would be marked by such thoughts as being insufficient without others, having to have others around to feel comfortable, and marked by such behavior as constantly seeking out others to be with, talking to others, etc. At the other end of this construct is extreme interpersonal independency, which would be marked by such thoughts as never needing others, having to be alone to feel comfortable, and such behaviors as spending time alone, not starting conversations with others, etc. A person functioning at either of the extremes on this dimension would be considered dysfunctional or psychopathological; between these two extremes lies a wide range of normal dependency-independency options.

Research has shown that most constructs are more common at their middle range, and less common at their extremes. As such, if those constructs related to personality or behavior that are related to psychopathology could be identified, then it would be possible to identify those points along the continua where abnormal or extreme patterns could be identified. For example, using the dimension of interpersonal dependency-independency, it might be possible to identify a point along that continuum where the person is either so dependent or independent it causes distress and/or interpersonal problems for the person. It would be at those points we would talk about the person crossing an imaginary line from normal to psychopathological functioning (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1. A dimensional approach to dependency.

A. Trait versus Symptom Approaches

Dimensional models of psychopathology can be viewed as typically being one of two major types. Some dimensional models focus on underlying theoretical dimensions or traits that might explain abnormal behavior, while other focus more on the range of symptoms or descriptive features of the dysfunctional behaviors themselves. Trait approaches are more theoretical than symptom approaches, and typically have an associated theory of normal personality as well as psychopathology, while symptom approaches focus more on the elements of psychopathology alone.

There are a number of trait approaches to psychopathology, and all cannot be described here. The work of Hans Eysenck is a good example of this approach, however, and will be used to provide an example. In Eysenck’s earlier research, he identified two basic dimensions to normal and abnormal behavior. One of these was the dimension of introversion-extroversion, which had extremes of being highly introverted (shy, retiring, isolated) and highly extroverted (outgoing, sociable), while the other was neuroticism (which had two extremes of stable versus unstable patterns; where instability is marked by such attributes as anxiety, physical complaints, moodiness, etc.). According to Eysenck’s research these two personality dimensions were unique from each other. An individual’s placement on each dimension, according to Eysenck, reflects a basic disposition on the part of the individual which likely could be seen in different situations that the person finds him/herself in, and also lasts across time.

Within Eysenck’s model of functioning, psychopathology is identified at the extremes of each dimension. Thus, a person who is “too” extroverted could be said to be dysfunctional; similarly, a person “too” high on neuroticism could be said to be dysfunctional. Eysenck developed questionnaires to measure these dimensions which allowed clinicians to identify how much of these dimensions were represented by an individual, and thereby identify if the person was in the normal range of functioning or not.

A later addition to Eysenck’s theory was a third dimension, referred to as psychoticism. This dimension was theoretically distinct from the other two, and reflected an underlying tendency toward more extreme forms of abnormal behavior, including insensitivity toward and lack of caring about others, and opposition of accepted social customs.

A mental health professional using Eysenck’s system to describe psychopathology would not talk about a given individual as “extroverted,” “neurotic,” or “psychotic,” but would rather talk about an individual as being high on these dimensions. The mental health professional would know that certain forms of thought, emotion, and behavior are related to these dimensions, and would explain psychopathology in terms of these underlying trait dimensions.

As stated previously, Eysenck’s is just one of a number of trait approaches to psychopathology. One of the major issues that has been addressed by theorists who use these models has been that of trying to develop a comprehensive and exhaustive system. In recent years, there has been considerable discussion about what are referred to as the “Big Five” personality traits that might explain most human behavior. These five factors include neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. While we will not discuss the adequacy of this model here, it is important to note two elements: first, that many theorists are beginning to converge on the importance of these five factors in personality, and second, that one of these dimensionsmneuroticism–is explicitly oriented toward identifying abnormal behavior of a neurotic type (anxiety, physical complaints, nervousness, edginess, etc.).

As opposed to trait models of psychopathology, there are symptom dimensional approaches. One prominent example of this type of approach has been with regard to the personality disorders. Within the DSM-IV, there are 11 recognized personality disorder diagnoses. As is true for other diagnostic categories, DSM-IV lists the descriptive features of these disorders, and presents them as unique (although a given individual could have more than one diagnosis simultaneously). An alternative perspective to conceptualizing types of personality disorders is to conceptualize personality as having a number of dimensions, which at their extreme represent dysfunctional patterns of interpersonal relating. Such an alternative approach would view personality features in terms of their symptoms, as well as in terms of the severity of these symptoms.

Symptom-based approaches, as seen in the area of personality disorders, can be imagined for most types of psychopathology. In the area of depression, for example, one can imagine that rather than diagnosing an individual as depressed or not based upon whether they meet certain diagnostic criteria, a psychopathologist could describe the severity or depth of depression. Such an approach would require a psychopathologist to determine the key symptoms of depression, to evaluate the severity of each of these symptoms, and then determine the overall depth or severity of depression for a given individual. The fact that the end result is an index of severity, though, means that an underlying dimensional, rather than categorical, approach has been used to conceptual and describe depression.

Dimensional approaches to most forms of psychopathology exist. Typically, the assessment of psychopathology using such approaches relies on questionnaires, which are self-report means to determine the number and severity of different symptoms the person may be experiencing. A large number of trait and symptom questionnaires have been developed, predominantly by psychologists working in the fields of personality and psychopathology. A listing of all published questionnaires and psychological tests can be gained by examining the Mental Measurements Yearbook, which is an annual publication of the Buros Institute.

B. Models of Psychopathology

Psychopathologists are not content with conceptualizing and describing categorical and dimensional aspects of psychopathology. Another key activity of psychopathologists is to develop theoretical models that can potentially explain the cause, course, and required treatment of these disorders as well. A large number of theoretical models have been developed to attempt to explain psychopathology, many of which are very complex and well beyond the scope of this research paper. An excellent starting reference for interested readers is Abnormal Psychology, by Davison and Neale (1991).

Models of psychopathology fall into several major categories. One major dimension which can be used to think of these models is whether their focus is on factors that are external or internal to the person. Models that focus on external factors might place an emphasis on such issues as early childhood experiences, family dynamics, traumatic experiences, and even social and cultural issues that might lead to different forms of problematic behavior. These models are likely to focus on the need for changes external to the individual to correct psychopathology, including marital and family therapy. Some theorists who adopt this type of environmental or social perspective also focus on the need to change societal or cultural variables to lower the likelihood of some forms of psychopathology. For example, it has been argued that some eating disorders are encouraged by the value that society places on thinness, and that by changing societal values, we may actually be able to lower the future likelihood of some eating disorders.

Theorists who focus on factors internal to the individual typically adopt either a biological or a psychological perspective. Biologically oriented theorists might focus on genetic contributions to psychopathology, structural problems in the nervous system that cause abnormal behavior, or neurological processes that can be disordered and lead to psychopathology. These theorists are likely to focus on biological treatments to psychopathology, including psychoactive medications. A large number of medications for treating psychological disorders exist, many of which have documented benefit.

The third major theoretical approach to psychopathology is psychological in nature. Such approaches focus upon psychological models of both normal and abnormal personality, and try to explain psychopathology in terms of these processes. Within the psychological approaches are a number of discrete models, including psychoanalytic, behavioral, cognitive, humanistic, and other theoretical approaches. While all of these models share the assumption that there is something within the individual at the psychological level that explains abnormal behavior, the specifics of each model vary dramatically, as do the therapies they promote.

In summary, psychopathology researchers not only classify, diagnose, and assess abnormal behavior, but also are interested in the causes, course, and treatment of these conditions. Different models are used in the effort to explain psychopathology. While some models appear to be better suited for some forms of abnormal behavior, others may be more appropriate for other conditions. It is also possible that a given form of psychopathology, such as anxiety, may have multiple causes, which may vary from person to person having that disorder. Humans are extremely complex, and the large number of approaches helps to encompass that complexity in the way psychopathologists conceptualize their subject field.

IV. Future Issues in Psychopathology

As the above reveals, psychopathology is an intricate and often perplexing field of study. Although there are a large number of issues that face the field, major issues include the future of categorical and dimensional approaches, theoretical models, and treatment issues. Each is discussed in turn below.

A. Categorical and Dimensional Approaches

Both of the categorical and dimensional approaches to psychopathology face the issues of comprehensiveness and distinctiveness. How many diagnoses or dimensions, respectively, adequately account for the range of human dysfunction? Are these distinct diagnoses and dimensions, or is their overlap such that they call into question the theoretical basis for the approach to psychopathology?

Another question that both approaches face is how best to assess psychopathology. As has been stated, each of these approaches has its own methodology for assessment. Categorical approaches lend themselves to diagnoses, which are typically constructed as a result of interviews with individuals, and the decision as to whether the given individual qualifies for one or more diagnoses. Dimensional approaches are most often assessed using questionnaires that assess one or more dimensions of psychopathology, using traits or symptoms as the conceptual basis for assessment.

Interview and questionnaire assessment strategies are not necessarily contradictory, and many psychopathologists believe that using both leads to a more comprehensive understanding of the individual in question. It remains for the field to adequately address which strategy or strategies are best within each approach, and how best to integrate these two types of assessment.

B. Theories of Psychopathology

Theories of psychopathology, as is true for all scientific theories, are tested against their explanatory power. Within psychopathology, many research methods exist to test theoretical models, including the ability to discriminate groups with different types of psychopathology, or the correlation between certain theoretical constructs and the severity of psychopathology. The field of psychopathology is rich with research questions.

Psychopathology research is notoriously difficult to conduct for a number of reasons, including the large number of definitional, assessment and theoretical perspectives already discussed. Further, it is often difficult to easily obtain large numbers of research subjects that clearly have a distinct form of psychopathology, and for ethical reasons it is often not possible to conduct the experimental types of studies that might best test different theories of psychopathology. Finally, a good number of different forms of psychopathology need time to develop (indeed, sometimes it is the course of different disorders that itself is the object of scientific study), which requires long-term research funds and geographical stability of both researchers and research objects. Such control is not easy to obtain in the real world.

Despite the above problems, research in the field of psychopathology is increasingly driven by strong theoretical questions, and the answers to these questions are slowly being accumulated. The field has begun to contrast competing theories, and the overall adequacy of some theoretical models is beginning to become clear. It can be expected that over the next decades some “best models” for different forms of psychopathology will emerge.

C. Treatment Issues in Psychopathology

Many psychopathologists enter the field because of a desire not only to understand, but also to help people with behavioral problems. One hope is that with accurate assessment and diagnosis, treatment options may become clarified. Although there does not yet exist a clear correspondence between different forms of psychopathology and treatments, the field has advanced considerably in this direction. For a given disorder there likely are several viable treatments, some of which may have better success rates, but all of which have some potential for helping an individual in distress. With increasing sophistication of assessment, diagnosis, and conceptualization, it is likely that treatment of psychopathology will become an even more complex and successful enterprise in the future than now.

Bibliography:

- American Psychiatric Association (1994). “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-IV.” Washington, DC.

- Buros Institute (1992). “Mental Measurements Yearbook.” Gryphen, Highland Park, NJ.

- Davison, G., and Neale (1991). “Abnormal Psychology,” 5th ed. Wiley, New York.

- World Health Organization (1979). “International Classification of Diseases,” 9th ed. Geneva, Switzerland.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.