This sample Resilience Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of psychology research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Every live thing is a survivor. —Annie Dillard

In this research-paper, we introduce you to resilience, a recent and promising concept in the field of psychology. Given the burgeoning number of studies and therapeutic applications based on this concept, resilience is likely to play an increasing role in 21st-century psychology. Both researchers and practitioners are discovering that most human beings are remarkably hardy. We summarize the surprising findings on the resilience of survivors who have endured such traumas as sexual assault, school violence, combat, and natural disasters. We also discuss the implications of resilience research for using psychological interventions that uncover strengths, identify coping abilities, and promote resolve.

Resilience comes from the Latin word resilire (“recoil”). To resile literally means to bounce back, rebound, or resume shape after compression. For example, a basketball typically has good resilience, but if it is deflated, it loses its potential to bounce back. In physics, the concept of resilience involves the elastic strain energy of material. Resilient material can endure the strain of being tightly compressed and then return to its original shape without deformity. Ecologists, political scientists, and economists have also found productive ways to apply the concept of resilience to their fields.

Psychologists have taken the notion of resilience and applied it metaphorically to characterize the ability of a person to bounce back after being knocked down by adversity. In other words, psychological resilience is the degree to which someone can rebound to, or even transcend, his or her previous level of functioning after enduring the strain of a traumatic event. The concept has provided an exciting conceptual framework in the areas of health, stress, and coping. Instead of concentrating on identifying the psychological casualties of crises and catastrophes, many researchers now are studying how people can develop their potential, discover new resources, and flourish under fire.

We seem to live in a time of crises, catastrophes, and traumas. As a college student, you may have found yourself captivated by powerful scenes showing injured and distraught people reeling from the shock of the shootings at Virginia Tech University. Such violent scenes typically make up the top stories of television news shows because producers follow the slogan, “If it bleeds, it leads.” Whether the traumas involved sexual assault, combat, or natural disaster, popular media typically depict most survivors as pathetic victims who are likely to be permanently scarred. Occasionally, the media will highlight just one or two individuals as inspiring heroes who overcame extraordinary obstacles. However, in contrast to these misleading portrayals, the vast majority of trauma survivors are neither helpless nor superhuman. Instead, they are regular people coping actively, being resilient, and doing their best to adapt.

You may be surprised to learn just how common it is for people to report that they have benefited psychologically from coping with a range of painful, even traumatic, experiences. Of course, during the crisis itself, people endure tremendous torment, suffering, grief, fear, and rage. They find themselves unable to perform their jobs, concentrate on their studies, and handle the day-to-day tasks of living. In the midst of the chaos and turmoil of the crisis, people may feel alienated, confused, and overwhelmed. At the same time, although not as obvious, most trauma victims are immediately demonstrating resilience by their initiative, fortitude, compassion, and beginning sense of hope.

Experiencing Resilience: Seeing Beyond The Victim

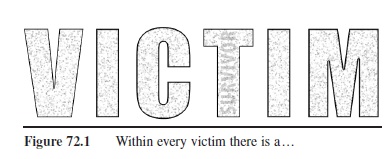

Go ahead and glance quickly at Figure 72.1. What did you see? The word “VICTIM,” right? The letters forming the word are certainly large and clear for anyone who briefly scans the figure.

Now, return to the figure and examine it more carefully. What smaller, fainter word is embedded within “VICTIM”? (The answer appears at the end of this chapter.)

Think back on a televised scene of people confronted by a traumatic event. What was more vivid and obvious to you in the midst of the crisis—their ordeals and sufferings as victims, or their personal strengths and capabilities as survivors? Psychologists who focus on resilience look for ways to find the survivor within the victim.

The Momentum for Resilience

When researchers conduct follow-up studies months or years after the trauma, the vast majority of survivors—between 75 and 90 percent—report personal growth and positive transformations. Adding momentum to this emphasis on resilience, Martin Seligman and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (2000), Charles Snyder and Shane Lopez (2002), Jonathan Haidt (2006), and many other psychologists have been promoting positive psychology, a recent conceptual shift in the field. According to the positive psychologists, the traditional focus in the science and practice of psychology has been on studying deficits and disorders. In contrast, positive psychology explores positive facets of the human psyche, including the ability to transform and heal after trauma.

Figure 72.1 Within every victim there is a…

Figure 72.1 Within every victim there is a…

Counselors and therapists have also started to seek out human strengths, rather than only assess vulnerabilities and uncover limitations, in their work with clients. For example, Dennis Saleebey (2001) cautioned his fellow clinicians against merely cataloging disorders and diagnosing dysfunctions. Such a mind-set could foster a victim mentality. Instead, he advocated using counseling and therapy for helping clients to enhance the coping skills they may have overlooked, to use their untapped resources, and to pursue their personal dreams. By building on strengths, psychologists and counselors can demonstrate that successful empowerment strategies do not give power to their clients. Instead, such approaches enable people to discover, develop, and exercise their own strengths, talents, wisdom, and resilience.

Resilience is also evident in the typical developmental crises that people face as they chart major transitions in their lives. When you made the move from high school to college, there was probably someone who played a part in helping you with the decisions and questions you confronted as you took that step. This person did not make these decisions and answer the questions for you. Instead, he or she appreciated your dreams and potential, along with your doubts and fears. This individual did not give you power. But by listening to your concerns, understanding your dilemmas, and validating your hopes, the person’s support helped you discover your own power and resilience.

Experiencing Resilience: Your Story

Everyone has been through adversities and hardships. Pick a time in your life in which you bounced back from a major disappointment, misfortune, or even trauma. Once you have made your choice, take a few minutes to reflect on that experience by answering the following questions:

- How did you manage to be so resilient?

- Who helped you see your resilience and strengths?

- In what ways are you a different person as a result of that experience?

- How did your relationships with others change as a consequence?

- What important lessons about life did you learn?

Your life is marked by both tragic and joyful turning points. How you coped with them has contributed to the development of the personal qualities, such as determination and sensitivity, that form your character. Moreover, the bonds that you formed with other people during those times are likely to be deep and lasting. The lessons you learned about what it means to be a member of a group, family, or community will serve you well. Keep your own experience of resilience in mind as you read this chapter. As we discuss the theory, research findings, and case examples, think about your own successful strategies and the ways in which you support the resilience of others.

Resilience As A Reciprocal Process

Some early theorists of resilience conceptualized it as a personality trait that characterized those individuals who withstood major stressors. Several scholars used such terms as “invincible” and “invulnerable” to portray such people. Theorists proposed that these resilient individuals had identifying personality traits, such as ego strength, sense of coherence, temperament, and optimism. The assumption of these conceptualizations was that some extraordinary individuals have stable and generalized dispositions that make them consistently resilient across all situations and virtually throughout their lives. Resilience was a quality that emanated from within these exceptional people.

Although researchers have found links between personality characteristics and resilience, critics of this perspective have expressed concerns and identified several limitations. First, grandiose labels, such as “invincible,” suggested that these people came through all adversities unscathed and untroubled. Second, the narrow focus on personality failed to recognize the vital role that an individual’s environment can play in promoting resilience. Third, the theorists assumed that personality traits caused resilience, but many studies have documented that an experience of resilience can actually enhance such traits as optimism, ego strength, and sense of coherence. In other words, resilience is not a static personality trait, but a complex, reciprocal process.

Resilience as Recovery

Later theorists defined resilience as the ability to recover from a trauma without developing any psychopathology, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or clinical depression. Resilience, therefore, is the absence of any psychological disorder following a significant stressor or crisis event—to resile psychologically is to survive by recovering from a trauma and returning to a state of normal functioning without any pathology. Other scholars have pointed out that the primary limitation of this conceptualization of resilience is that it is defined by the absence, rather than the presence, of a condition. Just as positive health is much more than merely the absence of illness, the notion of resilience suggests a more positive and richer construct.

Resilience As Post-Traumatic Growth

Many recent theorists conceptualize resilience as a process of rebounding from adversity to achieve a positive transformation and transcendence. Resilience is more than merely coping with crises and surviving them without developing a mental disorder. Instead, to resile is to thrive by achieving post-traumatic growth (PTG). It is not unusual to hear people later describe their crisis experience as “the best thing that ever happened to me.”

Such theorists as Lawrence Calhoun and Richard Tedeschi (2006) have described how victims of trauma can grow psychologically as a result of how they handle troubled times. They asserted that most people prevail in times of crisis to forge lifelong personal strengths and values. Consistent with their conceptualization, Tedeschi and Calhoun pointed out that cultures throughout history have recognized that individuals can change in dramatically positive ways as a result of encountering devastating events.

According to this view of resilience, individuals may experience profound and positive changes in their perceptions of themselves, their relationships with others, and their philosophy of life. These benefits include feeling more confident, becoming more self-reliant, growing closer to others, disclosing more, feeling more compassion for humanity, appreciating life more deeply, reviewing priorities, and experiencing a more intense sense of spirituality. Ultimately, from this perspective, resilience is the process of victims becoming survivors who go on to thrive in their lives.

Resilience Research

Initially, resilience researchers focused on children, discovering that many young people were surprisingly robust, thriving under difficult chronic conditions, including extreme poverty, family violence, institutional settings, and prejudice. After four decades, this research has consistently found that several factors promote resilience among children and youth. These protective factors include supportive caregivers, meaning in life, effective regulation of emotional arousal, and problem-solving abilities (Masten & Reed, 2002).

More recent research has documented that the majority of children who experience specific traumas, such as sexual assault or the death of a parent, do not develop psychiatric disorders. Resilience, in fact, is the rule, rather than the exception, for people of any age who are facing traumatic events. More recent studies have explored resilience among adults and have found that resilience is much more common than was once believed (e.g., Ryff & Singer, 2003). Life history studies of psychological well-being provide compelling evidence for the resilience of most—not just a few—people, both young and old, in the face of adversity.

Studies on successfully overcoming crises have been conducted in countries around the world, with people of all ages, and involving all types of adversities. Researchers have investigated both those who have directly confronted traumas and those who are indirectly involved—witnesses, coworkers, friends, relatives, and rescuers. Their findings have consistently demonstrated that the overwhelming majority of survivors overcome catastrophes and other adversities (e.g., McNally, Bryant, & Ehlers, 2003).

For example, in an epidemiological study Norris (1992) found that 69 percent of a representative sample of 1,000 Americans had experienced at least one extremely traumatic event during their lives. However, the lifetime prevalence rate for PTSD is only about 12 percent. Moreover, traumatic life experiences generally do not undermine long-term happiness or well-being: Humans are not merely products of their environment—even if the environment is horrific, threatening, and catastrophic. Instead, people show great resilience, ingenuity, and resourcefulness.

Hundreds of studies on the process of resilience have consistently identified four general factors that promote successful resolution of crises and traumas. These four pathways to resilience are social support, making meaning, managing emotions, and successful coping strategies.

Social Support

Resilient people are not islands unto themselves. Research on social support has shown that relationships offer survivors many vitally important resources such as affection, advice, affirmation, and practical assistance. Although the traumatic experience of victimization can initially provoke a sense of isolation and alienation, resilient survivors quickly turn to others.

As Marilyn Berscheid (2003) pointed out, some of our greatest sources of strength in troubled times are other human beings. In American society, with its strong value of rugged individualism, we typically do not appreciate just how embedded we are in a complex web of interdependence throughout our lives. However, from birth to death, our lives are interwoven in an intricate tapestry of relationships that nurture, protect, enliven, and enrich us. Close-knit families, cohesive work groups, life-long friends, and a sense of community provide buffers to the inevitable crises, adversities, and challenges of life. Social support improves physical and mental health, promotes recovery from illness, and is particularly crucial to people who are going through periods of high stress.

Like most other species, humans appear to be hardwired to turn to others in times of threat. In particular, people in crisis have a profound need to share their stories quickly with others. Rimé (1995) found that people shared a vast majority of their emotional experiences—over 95 percent—within a few hours. When individuals confide their traumatic stories in others, they typically experience immediate and positive physiological changes, including reduced blood pressure and muscle relaxation.

Making Meaning

Humans are the only meaning-making species, but psychology has practically ignored the subject of human meaning. Even though they have confronted traumas, people who go on to lead meaningful lives have greater satisfaction, experience more positive emotions, and evidence greater vitality (Emmons, 2003). Resilient people are more likely to share their adversities with others. In the telling of their stories, themes emerge that eventually shape their own sense of personal identity and family legacy. In other words, the narratives that they create do more than organize their life experiences. They affirm our fundamental beliefs, guide important decisions, and offer consolation and solace in times of tragedy.

Our sense of identity—our storied selves—rests on our ability to tell a coherent narrative of our past experiences, current circumstances, and future dreams. However, in times of adversity, the narrative fabric of our lives is torn. The pieces no longer fit and they do not make any sense. The process of resilience, on the other hand, involves reweaving our shredded lives once again into a meaningful and integrated whole. Like a message written in code, the meaning of a crisis is not readily apparent. However, we are compelled to make sense of our traumatic experience, discover its point or purpose, tie together the loose ends, and make connections that previously escaped us.

Building on his pioneering work on Holocaust survivors, Vicktor Frankl (1969) promoted the achievement of meaning as the foundation of resilience. In his research on loss and grieving, Christopher Davis (2002) has identified two fundamental and different processes that are involved in meaning making. These two dynamics are making sense of the loss—determining the “how”—and finding benefits that emerge from the experience—discovering the “why.” In one study, Davis and his colleagues interviewed caregivers who had lost a loved one. In follow-up interviews 6, 13, and 18 months after the death, they found that those who had made some sense of the death and had found some benefits, such as the loved one being at peace or the caregiver now resuming his or her life, were more resilient.

Making sense of adversity often goes on at different levels. One level of understanding the crisis concerns discovering the sequence of events, the causes and effects, and the underlying dynamics. Putting together these pieces of the puzzle can help someone gain a cognitive mastery by understanding the physical, social, environmental, economic, psychological, or historical forces that created the crisis. For example, if you have had a close family member diagnosed with a life-threatening medical condition, you and your relatives probably gathered extensive information regarding its prognosis and possible treatments. At a deeper level of understanding, you and your family also worked to integrate this threatening diagnosis into a consistent worldview and spiritual framework.

All adversities are victimizing experiences in one way or another. However, once people begin the process of resilience, most quickly shed the role of victim. Few individuals want to see themselves as poor, pathetic victims. Resilient people often favorably contrast the reality, however bad, with hypothetical possibilities that would have been much worse.

For example, when you have encountered people after they have experienced a traumatic event, you have likely heard them describe the painful incident and its consequences with the amendment “but it could have been worse.” Your friends may have concluded an account by exclaiming how lucky they were, compared with what might have been. If their car has been destroyed in an accident, they will point out that, if the circumstances had been slightly different, they could have been killed. If a family member has been struck with a serious disease, they will declare that they could have been afflicted with an even more debilitating disease.

Resilient individuals are better able to identify benefits or gains that they have made from adversity. In fact, most feel more self-confidence, have a deeper appreciation for life, fashion closer relationships with others, and report greater wisdom. Looking back on their trauma, many see themselves as having been on a mission and having served a higher purpose. As one survivor stated, “I just don’t believe that all this stuff happened for no point and for no reason” (Milo, 2002, p. 127).

People who achieve resilience are able to identify how their lives are richer, deeper, and more meaningful by dealing with misfortune. They may describe the trauma as “a blessing in disguise” that has transformed their lives. They may have discovered some things about themselves that they found upsetting at first, but they go on to learn important lessons from the experience (Wethington, 2003). Survivors often give meaning to their tragedies by advocating for political change and promoting public awareness of the problem (Milo, 2002).

Regulating Emotions

The study of human emotions, for the most part, has been a study of negative feelings. If you type “anxiety” as your subject heading in PsycInfo, you will find thousands of studies. Change the topic to “anger,” and again you will have an overwhelming number of hits. Try “depression,” and you will have similarly impressive results. However, if you submit “hope,” “compassion,” or “joy,” you will find only a handful of studies. Recently, though, both researchers and practitioners in psychology are turning their attention to positive emotions (e.g., Frederickson, 2002): They see positive emotions as a frontier of uncharted territory that holds vast potential for improving lives.

Adversity is a time of intense emotions, but a common assumption is that individuals in crisis have only negative feelings, such as fear, shock, and grief. Recent research has demonstrated that people actually experience not only painful reactions both also feelings of resolve, such as courage, compassion, hope, peace, and joy (e.g., Larsen, Hemenover, Norris, & Cacioppo, 2003). Acknowledging and giving expression to the gamut of emotions—both negative and positive—can promote resilience. Other researchers have explored how some survivors eventually transform their losses into gains. They found that even during the crisis experience itself, these future thrivers took pleasure in savoring the few desirable events that took place, appreciating discoveries that they had made, and celebrating small victories.

For example, in one study, caregivers told their stories shortly after the deaths of their partners by AIDS (Stein, Folkman, Trabasso, & Richards, 1997). Although their narratives were intensely emotional, surprisingly, nearly a third of the emotional words that caregivers used in their accounts were positive. At follow-up 12 months later, the survivors whose stories expressed more positive feelings showed better health and well-being. They also were more likely to have developed long-term plans and goals in life.

Another example of the expression of a positive emotion is laughter. Over the years, many counselors and therapists have dismissed the use of humor in times of adversity as merely a defense mechanism. They saw it as a cheap attempt to find comic relief and to avoid dealing with painful emotions. However, Milo (2002) identified humor as one of the important coping strategies used by mothers grieving for the death of their child. Humor is a positive emotion that embraces the enigma, paradoxes, and mysteries of adversity.

Experiencing Resilience: A Rainbow of Resolve

Think about the times that you have gathered with relatives and friends to grieve over the death of a loved one. In addition to shedding tears together, you probably also laughed as you recalled joyful times, offered expressions of love to one another, and perhaps savored the small but wondrous consolations of life. In these moments, you were all engaged in one fundamental process of resilience— expressing both positive and negative emotions.

Other Myths About Emotions

Another common myth is that emotions interfere with effective problem solving and successful coping. The typical view, particularly in Western societies, is that we must first “let out” our emotions or “put our feelings aside” in order to resolve a crisis rationally. However, new discoveries in neuroscience reveal that emotions are actually essential to productive thinking. Emotions can be viewed as impulses to take action. The origin of the word emotion is motere, the Latin verb “to move.” When you encounter someone in crisis, he or she is typically moving away from a threatening and dangerous situation. Once the person is in a safe place, he or she is likely to move psychologically toward resilience. At both times, emotions play a vital part in producing this necessary movement.

Recent evidence also casts doubt on the usefulness of the concept of emotional catharsis in portraying the complex and rich process of resilience. In contrast to strategies that give voice to a range of emotions, such as talking or writing about traumatic experiences, merely venting negative emotions by screaming and yelling has no psychological benefits.

Besides expressing their feelings in more productive ways, people use other strategies to manage their emotions during the process of resilience. These strategies include redirecting their attention, reframing the events, or taking the perspective of others. For example, a pilot trying to avoid an accident may focus entirely on carrying out the immediate tasks at hand, postponing any emotional expression until perhaps later. In addition to distracting oneself, a person can also reframe the adversity in a way that the feelings are not so overwhelming. After 9/11, rescue workers managed their emotions while picking up body parts scattered around the Twin Towers by reframing their grim task as an act of respect and honor for these final remains.

Experiencing These Ideas

Pick one of your own resilient experiences of dealing with a challenging situation. What emotions of distress—anxiety, sadness, or rage—did you experience? What role did these feelings play in meeting this challenge? What emotions of resolve—courage, hope, or compassion—did you experience? How did these emotions help you?

Broaden-and-Build View of Positive Emotions

Frederickson (2002) offered substantial support for a broaden-and-build conceptualization of positive emotions. Negative emotions narrow our options to those few actions that are usually adaptive in a threatening situation. When we are frightened, for example, we have an immediate urge to escape. Our thoughts quickly focus on finding the safest route to safety. Although we may chance upon a clever scheme for fleeing danger, fear propels us to take immediate and decisive action without wasting much time on reflection, consideration, and exploration.

In contrast, positive emotions can actually broaden our ways of thinking and acting. When people experience such feelings as love or joy, they are more likely to think creatively, to surprise themselves by what they are able to accomplish, and to explore new possibilities. Over time, people use these broadening experiences to build enduring personal resources that enhance their resilience: Cultivating positive feelings can help survivors to become thrivers.

Creative Coping

At least temporarily, traumas and crises rob us of our dreams for the future. However, as we engage in the process of resilience, we begin to envision new possibilities. Once articulated, goals serve as beacons that light the way for resilience. When they begin to see a future, survivors gain a sense of direction and hope, become more motivated, and increase their momentum toward resolution.

Resilience: Personal Growth And Clinical Interventions

Traditionally, psychologists who offered crisis intervention and trauma therapy had a tendency to focus on the adversity and its negative impact while losing sight of a client’s coping abilities. Unfortunately, clients who are in crisis have the same inclination. Less in touch with their personal resilience, they can feel overwhelmed not only by the circumstances but also by their sense of hopelessness, powerlessness, and helplessness. These feelings can undermine their confidence, sap their motivation, and cloud their vision of a future resolution.

You can begin to use the information from this chapter today as you listen to friends or family share stories of dealing with their crises and stress. You can make a special effort to consciously seek out their strengths—to search for those clues that illustrate a resilience strategy—as you continue to be sensitive to their ordeals. In other words, look for the survivor in their stories and not just the victim.

If you are considering the possibility of becoming a practitioner in the field of psychology, the concept of resilience can be a valuable reminder for you. When you recognize and value the resilience of your clients, you presume that they are survivors, not pathetic and passive victims. When you encounter someone in a crisis, you may feel tempted to come to the rescue. However, your fundamental role as a crisis intervener, or a friend, is far less heroic, but no less essential. Your job is like the carpenter’s assistant—helping others to use their own tools in rebuilding their lives.

Of course, these same observations apply to you and how you are likely to respond in a crisis. You will feel overwhelmed and distressed, and tend to focus on everything about you and the situation that is negative. Remembering that you also possess overlooked strengths and unmined capabilities will help you author a story that builds on your resilience and generates hope.

Although launching into adulthood should not be considered traumatic, it constitutes a developmental crisis. As a college student, you are navigating the taxing and cumulative everyday stress of personal decision making. You are determining who you are, what you believe, how to take care of yourself, and how you meet the demands of college life. Will you engage in risky sexual behaviors, excessive drinking and substance use, or destructive eating behaviors? Perhaps you feel pressure to excel academically because you are the first person in your family to attend college or, conversely, because there is a family legacy of college performance that you believe you must uphold. In your classes and conversations you are exposed to new ideas that may leave you questioning long-held values and beliefs, precipitating crises that are more existential in nature. Examining your ideas about spirituality, race, and politics can leave you feeling unmoored and lacking confidence. In these understandable moments of confusion or despair, try to recall the resilience you identified in the beginning of this chapter. Keep in mind how you demonstrated your resilience, who assisted you, and what lessons you learned that may be helpful at these times.

Rest assured that you are not alone—in either your desolation or your healthy striving. Let us return to the Virginia Tech example from the beginning of this chapter to examine the ways that these aspects of resilience can be explored and expressed. Following the heartbreak at Virginia Tech, honored poet and professor of English, Dr. Nikki Giovanni, composed an address that captured the conflicting and competing emotions of being a victim and becoming a survivor. The words of her address fully confronted the immensity of the horror on campus and connected it with the pain and striving of people around the world. Dr. Giovanni spoke at a convocation for the students and faculty following the tragedy. In her address, she asserted their collective identity by stating, “We are Virginia Tech,” and foreshadowed a future where the students and faculty—indeed, the entire Hokie Nation—survives the disaster by pronouncing, “We will prevail.”

Courageously, Dr. Giovanni concluded her words by predicting people will integrate the impact of the event in a way that promises PTG, stating, “We are alive to the imaginations and the possibilities. We will continue to invent the future through our blood and tears and through all our sadness.”

Experiencing Resilience: Heartbreak at Virginia Tech—We Will Prevail

Listen to Dr. Giovanni’s moving and inspirational address, accompanied by powerful photographic images, at http://www.caseytempleton.com/start/index.htm. (Click on “We Are Virginia Tech” at the top of the page.)

You may be able to recall just where you were and who you were with when you heard the news about the tragedy at Virginia Tech. How did you respond? Who provided comfort? To whom did you reach out? A unique aspect of the address is the extent to which Dr. Giovanni reached out, extending a connection from the horror in Virginia to tragedies around the world. In this way, she helped join communities in their sorrow, agency, and anticipation of a positive future.

Practicing Resilience

As you can see, you do not have to be a psychologist to practice resilience. In the following section we will translate research into the practice by discussing how you can help yourself and others move from merely surviving in a crisis to thriving and flourishing in life.

Reaching Out

Researchers have shown that relationships offer survivors many vitally important resources, such as affection, advice, affirmation, and practical assistance. This helpful reaching out response is particularly compatible for college students: A primary developmental task of young adulthood is creating and maintaining affiliate and intimate relationships. As you work through your everyday challenges and stress, you connect with classmates and roommates to find support, comfort, and nurturance and move toward resolution of problems. Opportunities to reach out to others and make a positive difference during troubled times can promote your own sense of resilience.

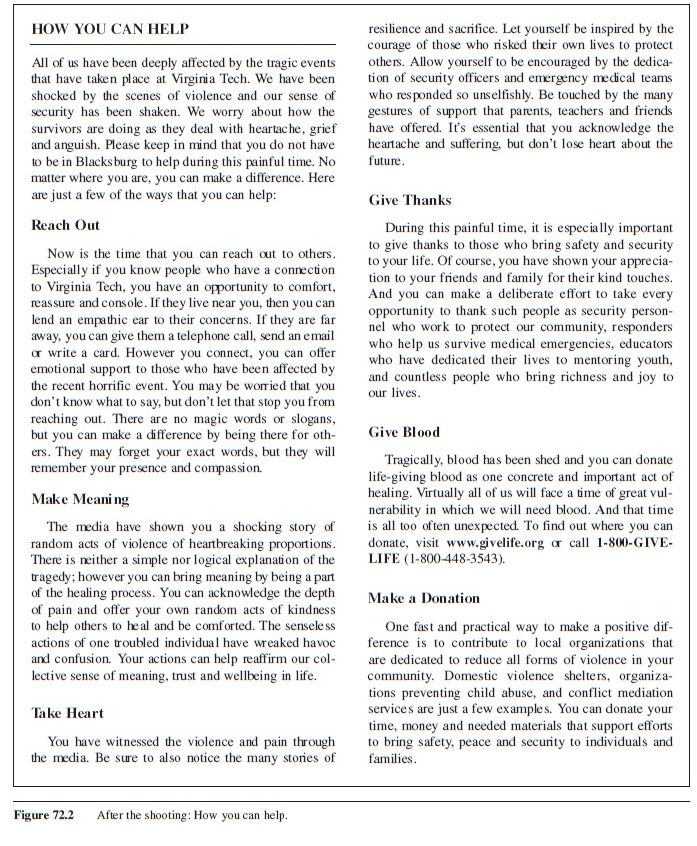

As faculty members teaching at a nearby university in Virginia, the authors of this chapter reached out after the shootings at Virginia Tech with an information guide for students and the public to use (see Figure 72.2). You may notice the handout does not label normal reactions to this horrific event as symptoms of pathology.

Rituals and Routines

Rituals and routines provide individuals, families, and communities with a way to affirm their identity and celebrate their roots. In your own family, you can identify customs that offer structure, meaning, and connectivity. You can then help yourself and fellow survivors to design new rituals and routines that safeguard, as much as possible, the traditions while accommodating the new circumstances.

Perhaps you have preserved rituals or routines in your own transition to college, connecting across the miles with your family to celebrate special occasions such as birthdays and holidays. Maintaining rituals and routines offers a sense of continuity and normalcy.

Psychologists and other practitioners can also serve as advocates in promoting community resilience. After Hurricane Katrina, school counselors in Pascagoula, Mississippi, implemented a community-wide project to help children and families reach out to one another at Halloween. The disaster had destroyed many homes, left dangerous debris scattered throughout the city, and made it impossible for many families to purchase costumes and candy for the children. To promote a sense of community, the high school students and other volunteers organized “Trunk or Treat.” They arranged for children to receive donated costumes and publicized that families could bring their little trick-or-treaters to the community’s high school parking lot, where over 70 decorated cars had trunks of candy to disperse. Children and families were able to celebrate a traditional holiday, experience a sense of normalcy, and reach out to one another in a safe space.

Making Meaning With Expressive Arts And Stories

Psychologists have developed a variety of techniques to help their clients, both young and old, to give expression to their own resilience. Using creative activities to tell one’s crisis story offers survivors an opportunity to begin to give form to raw experience, gain some sense of cognitive mastery over the crisis, and make important discoveries about their resilience. People tell their stories in a variety of ways—talking, drawing, sculpting, singing and writing, even playing—but whatever form their stories take, the process helps people to create meaning from the adversity.

How You Can Help

All of us have been deeply affected by the tragic events that have taken place at Virginia Tech. We have been shocked by the scenes of violence and our sense of security has been shaken. We worry about how the survivors are doing as they deal with heartache, grief and anguish. Please keep in mind that you do not have to be in Blacksburg to help during this painful time. No matter where you are, you can make a difference. Here are just a few of the ways that you can help:

Reach Out

Now is the time that you can reach out to others. Especially if you know people who have a connection to Virginia Tech, you have an opportunity to comfort, reassure and console. If they live near you, then you can lend an empathic ear to their concerns. If they are far away, you can give them a telephone call, send an email or write a card. However you connect, you can offer emotional support to those who have been affected by the recent horrific event. You may be worried that you don’t know what to say, but don’t let that stop you from reaching out. There are no magic words or slogans, but you can make a difference by being there for others. They may forget your exact words, but they will remember your presence and compassion.

Make Meaning

The media have shown you a shocking story of random acts of violence of heartbreaking proportions. There is neither a simple nor logical explanation of the tragedy; however you can bring meaning by being a part of the healing process. You can acknowledge the depth of pain and offer your own random acts of kindness to help others to heal and be comforted. The senseless actions of one troubled individual have wreaked havoc and confusion. Your actions can help reaffirm our collective sense of meaning, trust and wellbeing in life.

Take Heart

You have witnessed the violence and pain through the media. Be sure to also notice the many stories of resilience and sacrifice. Let yourself be inspired by the courage of those who risked their own lives to protect others. Allow yourself to be encouraged by the dedication of security officers and emergency medical teams who responded so unselfishly. Be touched by the many gestures of support that parents, teachers and friends have offered. It’s essential that you acknowledge the heartache and suffering, but don’t lose heart about the future.

Give Thanks

During this painful time, it is especially important to give thanks to those who bring safety and security to your life. Of course, you have shown your appreciation to your friends and family for their kind touches. And you can make a deliberate effort to take every opportunity to thank such people as security personnel who work to protect our community, responders who help us survive medical emergencies, educators who have dedicated their lives to mentoring youth, and countless people who bring richness and joy to our lives.

Give Blood

Tragically, blood has been shed and you can donate life-giving blood as one concrete and important act of healing. Virtually all of us will face a time of great vulnerability in which we will need blood. And that time is all too often unexpected. To find out where you can donate, visit www.givelife.org or call 1-800-GIVE-LIFE (1-800-448-3543).

Make a Donation

One fast and practical way to make a positive difference is to contribute to local organizations that are dedicated to reduce all forms of violence in your community. Domestic violence shelters, organizations preventing child abuse, and conflict mediation services are just a few examples. You can donate your time, money and needed materials that support efforts to bring safety, peace and security to individuals and families.

Figure 72.2 After the shooting: How you can help.

Using the following creative activities, you can transform your own crisis narratives into survival stories, using techniques that are similar to those of practitioners. In the process, you can pursue a successful resolution to a particular crisis.

Art of Surviving

People often become absorbed in using art to give form to their life experiences. When those life experiences are painful, frightening, or tragic, many children spontaneously draw pictures of the crises they face and the ordeals they suffer. You can learn from children and give expression to your own resilience during troubled times. Drawing pictures about your perseverance, resourcefulness, and creativity gives you an opportunity to recognize your own strengths and contributions to the resolution process. You, like children, can also use drawings to portray the help that others gave you, the lessons you have learned from the experience, and the ways that you are stronger now that you have survived.

If you have a conversation with people about their art, you will want to empathize with the victimization and be curious about the surviving. In other words, you acknowledge the crisis and you also ask questions to create opportunities for them to talk about their endurance, courage, compassion, joy, and hope. You can ask, for example, “I notice that this boy and his mama are smiling at each other in your picture. How are they able to smile even though their house was destroyed?” Such questions invite individuals to become more aware of the depth and richness of their own resilience.

Survival Journal

Many people keep journals, finding satisfaction in the process of transforming their life experiences into words. In troubled times, you can give voice not only to crisis narratives but also to stories of survival. Instead of focusing on the details of the crisis event, you can encourage yourself to elaborate on how you have been facing these challenges, managing the many changes in your live, and making sense of what is happening. The theme is that you may have been a victim of a crisis, but you are now a survivor who has shown determination, courage, and compassion.

Summary

In this research-paper we have emphasized that resilience is a new concept that is transforming the perspective of psychology. Psychological resilience is the degree to which people can achieve or transcend their previous level of functioning after a traumatic event. Theories of resilience have evolved from portraying it as a personality trait to conceptualizing it as a reciprocal process involving recovery and even post-traumatic growth. Research has documented a surprising level of resilience across cultures, among people of all ages, and under a variety of adversities. Studies of the process of resilience have found general support for four factors that promote resilience: social support, meaning making, regulating emotions, and coping strategies. Practitioners, particularly those who do crisis intervention and trauma therapy, are now applying resilience to their work. You can use the concept of resilience to promote your own personal growth. In an emergency, something new emerges, and as a future psychologist or as a friend and family member now, you can be a helpful presence at this crucial time to invite the resilient survivor to arise, like a phoenix, from the victim.

(Answer to Figure 72.1: The word SURVIVOR is hidden in the letter T.)

References:

- Aspinwall, L. G., & Staudinger, U. M. (Eds.) (2003). A psychology of human strengths: Fundamental questions and future directions for a positive psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Berscheid, E. (2003). The human’s greatest strength: Other humans. In L. G. Aspinwall & U. M. Staudinger (Eds.), A psychology of human strengths: Fundamental questions and future directions for a positive psychology (pp. 37-47). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Bonanno, G. A. (2005). Clarifying and extending the construct of adult resilience. American Psychologist, 60, 265-267.

- Bonanno, G. A., Galea, S., Bucciarelli, A., & Vlahov, D. (2006). Psychological resilience after disaster: New York City in the aftermath of the September 11 terrorist attack. Psychological Science, 17, 181-186.

- Calhoun, L. G., & Tedeschi, R. G. (Eds.). (2006). Handbook of posttraumatic growth: Research and practice.

- Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Davis, C. G. (2002). The tormented and the transformed: Understanding responses to loss and trauma. In R. A. Neimeyer (Ed.), Meaning reconstruction and the experience of loss (pp. 137-155). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Echterling, L. G., Presbury, J., & McKee, J. E. (2005). Crisis intervention: Promoting resilience and resolution. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/Prentice Hall.

- Echterling, L. G., & Stewart, A. L. (in press). Creative crisis intervention techniques with children and families. In C. Malchiodi (Ed.), Creative interventions with traumatized children. New York: Guilford.

- Emmons, R. A. (2003). Personal goals, life meaning, and virtue: Wellsprings of a positive life. In C. L. M. Keyes & J. Haidt (Eds.), Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well lived (pp. 105-128). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Frankl, V. E. (1969). The will to meaning: Foundations and applications of logotherapy. New York: New American Library.

- Frederickson, B. L. (2002). Positive emotions. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 120-134). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Haidt, J. (2006). The happiness hypothesis: Finding modern truth in ancient wisdom. New York: Basic Books.

- Keyes, C. L. M., & Haidt, J. (2003). Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well lived. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Larsen, J. T., Hemenover, S. H., Norris, C. J., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2003). Turning adversity to advantage: On the virtues of the coactivation of positive and negative emotions. In L. G. Aspinwall & U. M. Staudinger (Eds.), A psychology of human strengths: Fundamental questions and future directions for a positive psychology (pp. 211-225). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Lepore, S. J., & Revenson, T. A. (2006). Resilience and posttraumatic growth: Recovery, resistance, and reconfiguration. In L. G. Calhoun & R. G. Tedeschi (Eds.), Handbook of posttraumatic growth (pp. 24-46). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Masten, A. S., & Reed, M. J. (2002). Resilience in development. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 74-88). New York: Oxford University Press.

- McNally, R. J., Bryant, R. A., & Ehlers, A. (2003). Does early psychological intervention promote recovery from post-traumatic stress? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4, 45-79.

- Niederhoffer, K. G., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2002). Sharing one’s story: On the benefits of writing or talking about emotional experience. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 573-583). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Norris, F. (1992). Epidemiology of trauma: Frequency and impact of different potentially traumatic events on different demographic groups. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 409-418.

- Rimé, B. (1995). Mental rumination, social sharing, and the recovery from emotional exposure. In J. W. Pennebaker (Ed.), Emotion, disclosure, and health (pp. 27l-29l). Washington, DC: American PsychoIogicaI Association.

- Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. (2CC3). FIourishing under fire: ResiIience as a prototype of chaIIenged thriving. In C. L. M. Keyes, & J. Haidt (Eds.), Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well lived (pp. l5-36). Washington, DC: American PsychoIogicaI Association.

- SaIeebey, D. (2CCl). Human behavior and social environments: A biopsychosocial approach. New York: CoIumbia University Press.

- SeIigman, M. E. P., & CsikszentmihaIyi, M. (2CCC). Positive psychoIogy: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55, 5-l4.

- Snyder, C. R. (2CC2). Hope theory: Rainbows of the mind. Psychological Inquiry, 13, 249-275.

- Snyder, C. R., & Lopez, S. J. (Eds.). (2CC2). Handbook of positive psychology. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Stein, N., FoIkman, S., Trabasso, T., & Richards, T. A. (l997). AppraisaI and goaI processes as predictors of psychoIogicaI weII-being in bereaved caregivers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 872-884.

- WesseIs, M. (2006). Child soldiers. Boston: Harvard University Press.

- Wethington, E. (2003). Turning points as opportunities for psychoIogicaI growth. In C. L. M. Keyes & J. Haidt (Eds.), Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well lived (pp. 37-53). Washington, DC: American PsychoIogicaI Association.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.