This sample Somatization and Hypochondriasis Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of psychology research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Somatization refers to multiple physical complaints for which there are no medical explanations, and that may be related to coping mechanisms or psychopathological states. This research paper will discuss the links of somatization and other somatoform disorders (e.g., hypochondriasis) to common psychiatric disorders, such as depression and anxiety. There will also be a focus on systems of classifying somatoform disorders, as well as the epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, cross-cultural, and clinical management of somatoform disorders.

Outline

I. Introduction

II. Systems of Classification

A. Escobar’s Abridged Construct of Somatization

B. Are “Medically Unexplained Somatic Symptoms” Always Psychiatric Symptoms?

III. Pathogenesis

A. From “Distress” to “Psychopathology”: is There a “Bridge”?

IV. Detection, Recognition, Diagnosis

A. Somatizers and Hypochondriacs: A Profile

B. Problems with the New Classifications

V. Cross-Cultural Issues

VI. Clinical Management

I. Introduction

A general conception in psychology and psychiatry that has been held for more than a century is that somatization represents negative emotions and/or rather intense psychological conflicts that have been unconsciously converted into physical symptoms or somatic sensations. The exact mechanism mediating this conversion process is unknown, although there is extensive speculation about its psychological, social, and biological underpinnings. Nonetheless, the subjective experience of having a physical illness is a compelling reality for the somatizing patient, which tends to persist despite reassurance from physicians that no medical explanation can be proffered for the patient’s complaints. The somatizer vigorously resists any efforts that are made to reframe his or her distress as a consequence of psychiatric disorder, (i.e., depression, anxiety) or even psychosocial stressors.

A conceptual difficulty in advancing the fields is the fact that somatization is a diagnosis always made by exclusion. Hence, there is always a chance that a heretofore undetected or yet-to-be discovered underlying physical disorder may account for the complaints. Medical disorders that pose the greatest difficulty for differential diagnosis obviously are those with multiple ambiguous symptoms (for example, lupus erythematosus or multiple sclerosis).

In order to reduce the rate of “false positive” diagnoses of somatization, diagnostic criteria for somatization have emphasized issues of severity, a polysymptomatic presentation, and the absence of positive physical findings as key elements for the diagnosis. When presenting symptoms cut across many organs/biological systems, the likelihood of a somatization diagnosis is much higher.

II. Systems of Classification

In the most recent psychiatric nosologies, the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 4th Edition (DSM-IV), and the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition (ICD-I O), the label “somatoform” is used to group clinical syndromes whose most distinguishing feature is the presentation of and preoccupation with physical symptoms or somatic sensations that remain without a clear medical explanation.

The syndromes that have been grouped under the rubric “somatoform” in DSM-IV are somatization disorder, hypochondriasis, conversion disorder, body dysmorphic disorder, pain disorder and undifferentiated/not otherwise specified somatoform disorder.

Somatization disorder is an entity that can be traced to older concepts in psychiatry, such as hysteria or Briquet’s syndrome. The criteria for this disorder are fairly stringent, such as age of onset before 30, several years of unsuccessful medical treatment with significant loss of functioning in one or more domains (e.g., occupational), many unexplained symptoms (in DSM-IV at least eight unexplained symptoms are required) spread across different physical sites or systems. This diagnosis has high validity and reliability indexes and generally leads to poor outcomes.

The other somatoform disorders in the DSM-IV have much less stringent criteria than does full-blown somatization disorder and their validity seems less clear. Undifferentiated somatoform disorder requires that the patient present with at least one unexplained symptom that persists beyond 6 months and causes significant functional impairment.

Hypochondriasis requires that the patient be preoccupied with having a serious disease, such as cancer, for at least 6 months, which persists despite medical reassurance. Body dysmorphic disorder is defined by a preoccupation with an imagined deficit in appearance, which at times may reach psychotic proportions.

Although DSM-IV and ICD-IO resemble each other more than did any of their predecessors, there are still significant differences between the two taxonomies in the case of several diagnostic categories, including dissociative and somatoform disorders. For example, the most pressing reason for mentioning “dissociation” in this research paper is the inclusion of “conversion disorders” under a superordinate dissociative class (F44)in the ICD-IO. In contrast, “conversion disorders” are subsumed under somatoform disorders in DSM-IE One additional reason to mention somatization/conversion in the context of dissociation acknowledges the historical cogenesis of dissociative and hysterical phenomena in nineteenth-century French psychiatry. In addition, DSM-IV highlights psychological elements thought to be at work in conversion disorder (e.g., temporal onset of conversion symptoms immediately after psychological trauma), whereas ICD-10 tends to elaborate the physical aspects of conversion symptoms.

Because of the limitations of current diagnostic classifications, a number of proposals have been made to reframe somatoform syndromes in simpler, more practical ways. These proposals suggest a somewhat different taxonomy than that appearing in the DCM or ICD systems, albeit with discernable areas of overlap, at least for the symptoms more commonly seen in primary care settings. For example, in 1991 Kirmayer and Robbins at McGill University proposed three forms of somatization in primary care. These are (1) high levels of functional somatic distress measured by the somatic symptom index of Escobar; (2) hypochondriasis, measured by high scores in an “illness worry” scale; and (3) somatic manifestation seen exclusively in patients with current depression or anxiety. Over 25 % of patients attending a family medicine clinic met criteria for one or more of these forms of somatization. Interestingly, these forms were only mildly overlapping.

G. Richard Smith’s (1994) review of the literature on the course of somatization and other aspects of the disorder, proposes four categories in his classification: (1) clear somatization disorder or SD (essentially the same entity as in DSM-IV); (2) subthreshold somatization (for patients with unexplained physical symptoms who do not meet all criteria for SD); (3) somatization with comorbid physical illness; and (4) somatization with comorbid psychiatric illness.

Smith’s review suggests that patients with fullblown SD perceive themselves as “sicker than very sick,” spending, on average, 1 week per month in bed. In addition, these patients, relative to medical controls, present with a greater number and intensity of psychological symptoms (depression, panic) and greater work and social disability. Interestingly, the strong belief held by SD patients that their health is “extremely poor” is not corroborated by research evidence. For example, Smith cites the mortality rate of SD as being equal to that of patients in the general population and significantly lower than that found in major depression. Perhaps most telling of all statistics cited by Smith is the fact that SD patients evince health care utilization costs at nine times the U.S. per capita average.

According to Escobar, parallel to patients with SD, those with subsyndromal SD also report increased sick leave, restricted activities, and avid use of nonpsychiatric medical services compared with the general population. Moreover, when somatization coexists with either physical or psychiatric illness (Categories 3 and 4 in Smith’s taxonomy), there is a significant amplification of the discomfort and disability typically associated with either class of illness when occurring in isolation. Smith notes that it has also been established that high levels of psychiatric comorbidity are much higher for somatizing patients than for nonsomatizing controls, particularly with respect to major depression, generalized anxiety, phobia, and some Axis II personality disorders, such as avoidant, paranoid, and self-defeating disorders.

A. Escobar’s Abridged Construct of Somatization

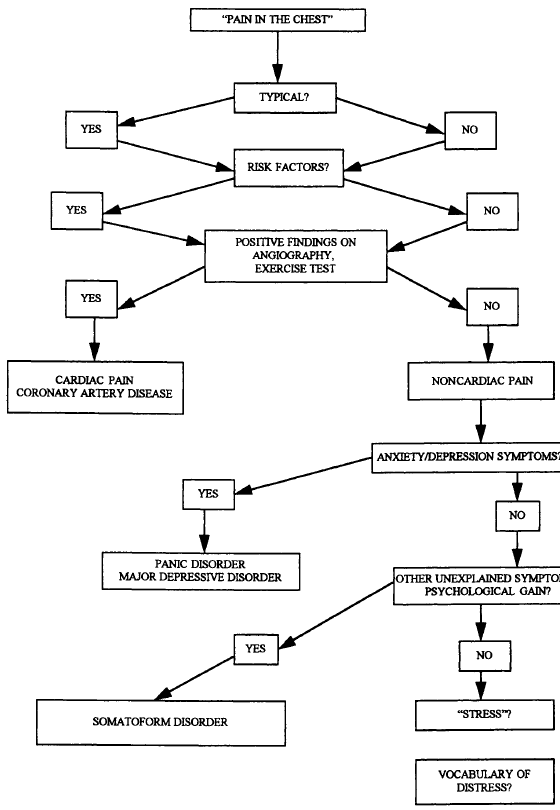

Because more than one-fourth of all patients seeking primary care services are somatizers and many of these would not be captured by the SD diagnosis in current nosologies, the first author (JIE) and his colleagues sought to develop methods of identifying and classifying SD and subsyndroma| somatization phenomena that would be feasible for use by primary care providers. In this context Escobar proposed an “abridged” somatization construct, along with a relatively simple series of interview probes to be used by the physician or lay interviewer. Figure 1 is a flowchart that provides a practical example of the probing logic for chest pain, a common symptom in a primary care setting. Essentially, male patients satisfy criteria for Escobar’s “abridged” somatization if they present with four or more unexplained physical symptoms that impairsome aspect of functioning and daily living, whereas females satisfy criteria with six or more unexplained symptoms. More recently, the WHO-sponsored international classification (ICD-IO) drafted a “primary care version” of the diagnostic criteria for SD and subsyndromal somatization that uses this more generic definition of somatizing patients as those “presenting with many unexplained somatic complaints.”

Figure 1. Probing logic for chest pain.

According to Escobar, a somatization symptom should be coded individually on the basis of its severity, frequency, and the degree of functional interference and disability it conveys. A rigorous system of probes should be used to rule out alternative explanations for a given symptom, such as the use of medications, drugs, or alcohol, or the presence of a physical illness or injury. High levels of unexplained symptoms elicited in this manner (e.g., more than four lifetime symptoms for males) imply “somatization.” Escobar’s extensive program of research on both general populations and primary care samples has validated his method of identifying the disorder by showing that patients who satisfy these abridged criteria independently evidence elevated scores on standardized measures of psychopathology, show high levels of utilization of inpatient and outpatient medical services, and present with greater disability in work, family, and social domains. Put another way, the validity coefficients (correlates) of Escobar’s abridged somatization construct have been observed to be similar both in direction and magnitude to the correlates of “full-blown” SD. These results are consistent with but do not prove a “dimensional” as opposed to a “discrete” view of the somatization phenomena. Interestingly, although the threshold for “full” somatization disorder required 13 or more unexplained symptoms in DSM-III-R, the threshold has been moved closer to that of Escobar’s in ICD-IO and DSM-IV. Thus, in the Diagnostic Criteria for Research in ICD-10 only six symptoms are required, while in DSM-IV only eight symptoms are now required, with the caveat that at least two of these must be pseudoneurological (e.g., numbness, blindness, seizures).

B. Are “Medically Unexplained Somatic Symptoms” Always Psychiatric Symptoms?

There seems to be some consensus, based on the reviews by Escobar, Noyes, Holt and Kathol, and Smith that prior to assuming that a somatic symptom that remains medically unexplained has a psychiatric basis, the symptom should have the following characteristics:

1a. The symptom is associated with a “primary” psychiatric disorder (e.g., major depression or panic disorder).

1 b. The symptom appears in close temporal proximity with certain life events such as overwhelming trauma or other severe stressors.

2. The symptom provides some sort of psychological “gratification” to the individual (e.g., “secondary gain” such as decreased work or family responsibilities) or represents a less-stigmatized (than mental illness) mode of expressing underlying chronic unhappiness (as in the personality “trait” of neuroticism).

3. The symptom becomes persistent, joins a conglomerate of other unexplained physical symptoms, setting in motion extensive use of health services and chronic dissatisfaction with medical care.

III. Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of somatization is unknown. A number of factors is thought to act in concert to produce somatization. One sociological explanation is that adoption of a “sick role” provides secondary gains to the person who adopts it (lowering of work responsibilities) while simultaneously shielding the individual from the stigma associated with mental illness. The “primary gain” associated with somatization, according to psychoanalytic theory, is the amelioration of intrapsychic conflict. There are also many other plausible psychological and biological explanations, some of which have been summarized by Noyes, Holt and Kathol.

One of these factors is autonomic arousal. Under the influence of stress or anxiety, patients experience heightened arousal and, with it, a host of mediated symptoms. Palpitations, shortness of breath, dizziness, sweating and other symptoms may all become a focus of health concern. Excessive worry about health, regardless of its source, may be another factor. Worried persons are vigilant and scan their bodies for sensations that then become an object of worried concern. By focusing narrowly on a body part, a person may intensify sensations arising from it, sensations that may grow distressing or even painful. Still another factor has to do with communication of distress. Some somatizers are unable to distinguish between emotions and bodily sensations and have difficulty communicating feelings (p. 741).

Somatizers may also have lower thresholds and tolerance for physical discomfort. For example, in experimental situations, the same stimulus that elicits a simple sensation of “pressure” in the nonsomatizer can elicit “pain” in the somatizer. There is speculation that this lower threshold is constitutional in nature.

The prevalence of SD or subsyndrornal somatization in general medical practice has risen over the last half century. This rise seems less attributable to an actual increase in mild, self-limiting physical symptoms (such as fatigue, headaches, and upper respiratory distress) than to a societal tendency to reclassify mild and benign bodily discomfort as symptoms of medical disease. In line with increased “medicalization” of benign transient symptoms is a growing list of “functional somatic syndromes” whose scientific status and medical basis remain unclear. These include chronic fatigue syndrome, total allergy syndrome, food hypersensitivity, reactive hypoglycemia, systemic yeast infection (Candida hypersensitivity syndrome), Gulf War syndrome, fibromyalgia, sick building syndrome, and mitral valve prolapse.

A. From “Distress” to “Psychopathology”: is There a “Bridge”?

Theoretical formulations within a variety of social and behavioral science disciplines, such as sociology, anthropology, and psychology, invariably link psychiatric disorders with “stress.” Because “distress,” regardless of its source, commonly is expressed in psychological or behavioral terms (e.g., “demoralization,” “anxiety, . . . . depression”), these formulations continue to hold significant influence on the mental health field. However, a distinction must be made between expressions of “distress” (or “stress-induced” states) and formal “psychopathologic” states. Psychiatric diagnoses that are distinct, reliably made, and predictable, such as endogenous/melancholic depression, do not seem to fit well the theoretical framework of the “stress spectrum disorder.” Quite naturally, the theorizing that linked “distress” to psychiatric disorder was transported to the field of psychiatric epidemiology, and therefore, instruments used in these surveys tend to be simple self-report measures of “distress.” In this zeitgeist, even a formal diagnostic system such as DSM-IV can be truncated to a mere symptom checklist, used by clinicians simply to elicit symptoms one by one. In the opinion of the authors, key elements in generating valid psychiatric diagnosis should include not only each reported symptom but also its intensity or severity, and the way in which it clusters with others symptoms and psychosocial attributes.

Somatization may be an interesting exception to the trend of reducing psychiatric diagnostic process to symptom inventories, at least in DSM-IV. Since it rules that in order to score a physical complaint as a psychiatric symptom the probing needs to scrutinize severity issues in addition to documenting medical visits and lack of clear medical explanations for the symptom. In our opinion, high levels of somatic symptoms represent a reliable entity, akin to the sturdier disorders in psychiatry such as melancholia. As such, somatization may be much more accessible to empirical scrutiny than most other symptomatic constructs in psychiatry.

IV. Detection, Recognition, Diagnosis

Somatization and its various syndromes, although well documented throughout the years, have baffled medical practitioners with their tendency to metamorphism as part of cultural evolution and the changing perspectives of the medical paradigms. For example, Barsky and Borus have argued that somatization is on the rise because “sociocultural currents reduce the public’s tolerance of mild symptoms and benign infirmities and lower the threshold for seeking medical but not psychiatric (italics ours) attention for such complaints. These trends coincide with a progressive medicalization of physical distress in which uncomfortable bodily states and isolated symptoms are reclassified as diseases for which medical treatment is sought” (p. 1931). In clinical settings as well as in common parlance, somatizers tend to be labeled in a derogatory manner. Curiously, however, these vernacular terms (such as “hysterics, …. Gomers” [acronym for Go Out of My Emergency Room], “turkeys, …. hypochondriacs,” and many others) seem to have more currency in describing the experience of dealing with these patients than do the more refined and euphemistic diagnostic labels.

The fact that somatoform disorders lag far behind other psychiatric diagnoses in terms of their proper recognition and visible research activity may be explained by their rather ambiguous nosological status. Problems in classifying these syndromes include issues of diagnostic validity and the excessive comorbidity that exists with other types of psychopathology. Also, since patients affected by these disorders believe their illness is “physical,” they reject psychological labeling or referral and are rarely seen in psychiatric settings. Moreover, they are unlikely to form “advocacy groups” such as those seen in the case of people with anxiety or mood disorders. It is likely, however, that many somatizing patients readily joint patient groups with more “medicalized” labels such as functional somatic syndromes like “chronic fatigue,” “TMJ,” “Fibromyositis,” “Multiple Chemical Sensitivity,” among numerous others.

The current age of cost containment has brought new awareness about these patients, since they are avid consumers of services and technologies, thus taxing health care systems excessively. Following suit with tradition, newly found characterizations of these somatizing patients prove colorful though still highly pejorative. Thus, the traditional “hysterics” or “hypochondriacs” at the medical clinics are becoming the “frequent flyers” at the corporate health headquarters.

Because of the ambiguity of their symptoms, treatment refractoriness and lack of psychological mindedness, somatizing patients use health services excessively, in pursuit of diagnostic confirmation or reassurance. This leads to heavy utilization of expensive technologies and often may result in unnecessary procedures being performed. It is as if medical care became an essential social support network and the patient role part of personal identity for these patients. Paradoxically, these patients also display chronic dissatisfaction with the care received, and may often seek financial compensation for their symptoms and “mishaps.” This latter factor, when added to avid service use and disability inherent in the disorder, makes somatizing syndromes some of the most expensive entities in medicine. Indeed, somatization is on a collision course with cost-containing trends in managed care.

A. Somatizers and Hypochondriacs: A Profile

Individuals affected with these traits, generally display a tendency to amplify physical symptoms and sensations. They also tend to endorse multiple physical symptoms involving various body areas. My impression (JIE) in working with many of these patients, is that there is a tendency to “overreport” not only physical symptoms, but also psychiatric ones, hence the high levels of psychiatric comorbidity that are well documented in the literature. In addition to over reporting physical symptoms, these patients also tend to overreport negative “experiences” (e.g., trauma, instances of being victimized, sexual abuse), relative to other clinical populations.

Contrary to much theorizing, “somatizers” are not a good model for “masked” psychiatric disturbances since they report very high levels of psychological distress. High levels of these unexplained physical symptoms seem to be a good marker for affective and anxiety syndromes, and possibly several other psychiatric disorders. Anxiety syndromes would primarily imply unexplained cardiopulmonary symptoms, while depressive syndromes would coexist with unexplained somatic pain in many sites, muscular-skeletal weakness, and pseudoneurological symptoms (e.g., numbness, amnesia). In advancing the specificity of somatization indexes, the authors are currently exploring clustering of somatic symptoms for the various disorders.

A glance at some DSM-IV and ICD-IO categories leaves one with the impression that in trying to make larger numbers of individuals fit the criteria, the “net” has become much less discriminating, and the “catch” much less specific. In the hands of less experienced clinicians, many of these nosologic categories end up as mere “symptom checklists,” simply eliciting symptoms as present or absent regardless of their severity or clustering attributes. Although this may be a convenient feature in the age of managed care, it flies in the face of traditional psychopathology that has relied on detailed anamnesis, natural course of illness, and precise dissection of symptom phenomenology in the creation of “valid” diagnoses. To counter the lack of specificity of many psychiatric syndromes, it is important to restore the Kraepelinian tenet, that the intensity or severity of the symptom, its temporal evolution, and its clustering, rather than the symptom per se, should remain the key elements in psychiatric diagnosis. Fortunately, in eliciting somatization symptoms, DSM-III-R and DSM-IV have drafted unambiguous rules. For example, the “probing” is expected to scrutinize severity issues in addition to documenting medical visits and lack of clear medical explanations for the symptom prior to scoring it as present. Thus, when elicited in this manner, high levels of medically unexplained somatic symptoms may represent more valid and reliable indexes than other symptom clusters. Besides, a medically unexplained symptom is more objective, more accessible to scrutiny, and, also, it may prove less intrusive, eliciting far less resistance from the individual affected than other psychopathologic concepts.

V. Cross-Cultural Issues

It is generally accepted that cultural influences may color the expression of somatization and hypochondriasis. Although it is often difficult to disentangle the contribution of ethnicity from other demographic factors (e.g., socioeconomic status: patients of lower socioeconomic status tend to somatize more than those of higher status), most studies reinforce the view that culture exerts a powerful influence in shaping symptom presentation and determining health-related attitudes. For example, in the United States the prevalence of somatization, based on counts of unexplained physical symptoms, is higher for some ethnic groups (e.g., Jewish and Italian Americans) than for others (e.g., Irish Americans). Also, relatively high levels of unexplained physical symptoms in the United States have been reported in the case of Middle Eastern, Southeast Asian, and Latino patients. However, there is also significant within-group variation among the different Southeast Asian ethnic groups and also among such Latino subgroups as Mexican American, Puerto Rican Americans and Cuban Americans.

It is conceivable that the type of symptoms presented by “somatizing” patients may differ in various cultural settings. International research reports reveal rather pathognomonic symptom presentations for patients with somatoform disorders in various cultures. For example, in Africa (Nigeria), “feeling of heat,” “peppery and crawling sensations,” and “numbness”; in India, “burning hands and feet, …. hot, peppery sensations in head”; and in Puerto Rico, headache, trembling, stomach disturbances, palpitations, and dissociative symptoms, all components of a syndrome called “ataque de nervios.”

Moreover, even within similar countries, such as European and North American, there are unique differences. For example, in North America there is an emphasis on immunologically based symptoms.

VI. Clinical Management

The clinical management of somatizing syndromes continues to be an area of active debate and improvisation. These disorders confront us both with diagnosis and therapeutic challenges because of their polysymptomatic (multiorgan) and polysyndromic (comorbid) features, their persistence, and their refractoriness to traditional interventions. The lack of psychological “mindedness” in somatizers poses serious hurdles to psychotherapeutic management and negatively affects adherence to psychiatric interventions. Because of the diagnostic dilemmas often faced, and possibly because these patients rarely present to mental health treatment settings, very few scientific data are available on how the various therapeutic interventions affect the most salient outcomes.

One of the few exceptions is the study by Smith, Rost, and Kashner on the effects of a brief intervention on costs of care, level of functioning, and clinical outcome. The intervention was followed by primary physicians and had several distinct features. These included the adoption of an understanding and reassuring attitude, taking the patient’s complaints seriously, performing a brief physical assessment during regularly scheduled visits, and an active avoidance of procedures and medications. The latter strategy prevents iatrogenic complications that often result from unnecessary medical and therapeutic interventions performed on these patients. It was found that when these procedures were followed, physical functioning improved and costs of care went down.

Noyes, Holt, and Katho| also emphasize the importance of regularly scheduled visits in order to reassure the somatizing patient that the physician is concerned about his or her well-being. At the same time, unscheduled visits are actively discouraged, since these tend to reinforce the patient’s well-honed tendency to amplify existing symptoms or to generate new ones.

Physicians themselves may need the support of colleagues or consultants in order to deal with negative emotions that arise when treating somatizers. Common emotions experienced by treating physicians are guilt and anger. Guilt may accompany the clinician’s attempt to set limits on frequent phone calls or unscheduled visits from demanding patients. It is not uncommon to experience anger when treating a particularly demanding and resentful patient, especially when he or she begins to test already established limits, and the provider may need a means to vent this anger or talk to a colleague so as not to direct the anger at the patient.

Regarding pharmacotherapy, the use of antidepressants has been proposed for a number of the somatizing syndromes including chronic pain, chronic fatigue, somatization, and hypochondriasis, whereas neuroleptic agents such as pimozide are advocated for delusional syndromes such as delusions of infestation and severe cases of dysmorphophobia. With very few exceptions, however, most of these claims are based on anecdotal reports. The first author (Escobar) is aware of two currently ongoing double-blind trials in this area, one on hypochondriasis and the other on dysmorphophobia. Results of these important studies were not available as of September 1997 (JIE).

Secondary syndromes, such as the somatic equivalents of anxiety and depression, would be expected to respond to traditional treatments such as antianxiety and antidepressant agents such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Few systematic data, however, are currently available.

Psychological treatments, such as cognitive-behavioral treatments aimed at enhancing emotional expression and correcting dysfunctional attitudes towards illness and patient roles have also received some empirical support of efficacy. Treatments based on the behavioral paradigm of exposure-response prevention have also been developed. These psychological treatments, while promising, are in need of further research and development.

Finally, on the basis of clinical experience and the studies described in a previous section, one would strongly predict the relevance of ethnic background to the processes of treatment seeking, adherence, and response of somatizing patients. Once again, however, there are no scientific data to provide guidance in this regard. This should become an important priority for future studies.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

- American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

- Barsky, A. J., & Borus, J. F. (1995). Somatization and medicalization in the era of managed care. J. Amer. Med. Assoc., 274, 1931-1934.

- Castillo, R., Waitzkin, H., Ramirez, Y., & Escobar, J. I. (1995). Somatization in primary care, with a focus on immigrants and refugees. Arch. Fam. Med., 4, 637-646.

- Escobar, J. I. (1995). Transcultural aspects of dissociative and somatoform disorders. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 18, 555-569.

- Kirmayer, L. J., & Robbins, J. M. (1991). Three forms of somatization in primary care: prevalence, co-occurrence, and sociodemographic characteristics. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis., 179, 647-655.

- Noyes, R., Holt, C. S., & Kathol, R. G. (1995). Somatization: Diagnosis and Management, Arch. Fam. Med., 4, 790-795.

- Smith, G. Richard, Rost, K., & Kashner, T. M., (1995). A trial of the effect of a standard psychiatric consultation on health outcomes and costs in somatizing patients. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry, 52,238-243.

- Smith, G. Richard. (1994). The course of somatization and its effects on utilization of health care resources. Psychosomatics, 35, 263-267.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.