This sample Students with Emotional and Behavioral Problems Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

This research-paper presents characteristics of students with emotional and behavioral problems within the conceptualization of child and adolescent psychopathology. Implications for children in clinical and school settings are included.

Outline

- Introduction

- Conceptualizations of Child and Adolescent Psychopathology

- Mental Disorders in Children and Adolescents

- Interventions

1. Introduction

Students who have significant emotional and behavioral problems necessitating professional intervention often are described as being ‘‘emotionally disturbed,’’ ‘‘behaviorally disordered,’’ ‘‘emotionally and behaviorally disordered,’’ or some similar term. Although these labels are in common use, they are broad and ambiguous and offer little help in understanding the nature, extent, prevalence, and implications of these problems in children and youth. This research-paper describes current conceptualizations of children’s emotional and behavioral problems and implications for schooling and effective interventions.

2. Conceptualizations Of Child And Adolescent Psychopathology

The development of research and knowledge in child and adolescent psychopathology has burgeoned during the past two decades or so. The current state of the research suggests that children’s emotional and behavioral problems can be conceptualized as internalizing or externalizing. Internalizing problems are characterized by anxiety, depressed mood, somatic complaints, withdrawal, and similar behaviors. These behaviors often are referred to as ‘‘overcontrolled’’ because the children show inhibited behaviors and spend much energy in controlling behaviors. These problems also are similar to what are commonly termed ‘‘emotional problems.’’ Externalizing problems refer to behaviors such as impulsiveness, aggression, inattention, hyperactivity, and distractibility. These behaviors are termed ‘‘undercontrolled’’ because the children lack the ability to control the behaviors. They are often referred to as ‘‘behavior problems.’’ Internalizing and externalizing behaviors can be conceptualized as being on a continuum where the range of behaviors shown may be from very withdrawn (internalizing) to highly active and perhaps even aggressive (externalizing). However, this range does not represent a true continuum because children may show many behaviors simultaneously, although some may predominate. For example, 25 to 40% of children with conduct disorder (CD) also are depressed, although the conduct problems may be observed more readily. Research has shown that the correlation between internalizing and externalizing patterns ranges from approximately .25 to .40. Moreover, some behaviors are associated with both internalizing and externalizing problems, for example, social skills deficits and academic difficulties.

When children demonstrate internalizing or externalizing behaviors of such seriousness that personal, social, and/or academic functioning is affected, they may be referred to mental health professionals. Children with externalizing behaviors are more likely to be referred for mental health care because they are more disruptive at home and in the classroom. Children with hyperactivity, aggression, and other externalizing behaviors account for approximately 50% of all referrals to mental health professionals. Inattention without hyperactive behaviors is seen most readily in the classroom. Children with internalizing problems are less likely to be referred because they generally are not disruptive and the problems are less likely to be detected easily by parents or teachers. However, exceptions to this trend do occur, for example, severe phobia or depression that leads to suicidal ideation or behavior.

Another important conceptualization of behavior is trait and state, which complements the internalizing– externalizing perspective. ‘‘Trait’’ refers to behaviors that are characteristic of children and are seen across a variety of settings and circumstances. ‘‘State’’ refers to behaviors that are a manifestation of the impact of the environment. The state–trait concept is important for helping to understand why children’s behaviors vary across settings. In schools, for example, it is common for children to exhibit off-task behaviors in one classroom but be more attentive in another classroom. Thus, the difference in behaviors might not be due to a trait; rather, it may reflect factors such as teacher management skills (state). Therefore, interventions may focus on the teacher and the setting rather than on the children. Children who have a high degree of a trait, however, may be more likely to show the behaviors in specific situations. Spielberger has conducted extensive research on anxiety and anger as having state and trait dimensions. Anxiety and anger tend to be constant traits, placing children at an increased likelihood of becoming anxious or angry in specific situations (state). Interventions often are directed toward reducing the magnitude of the trait as well as helping children to cope with anxiety and anger-producing situations.

2.1. The Taxonomy of Mental Disorders

A taxonomy is an orderly classification of objects, people, or other phenomena according to their presumed natural relations with each other. A taxonomy classifies according to mutually exclusive criteria; that is, the criteria can apply to only one specific member of a class, making the class unique. The concept is most often used in the physical sciences, such as botany and zoology, but it is also applied to human behavior. The taxonomy of mental disorders most commonly used in the United States is the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV). There are more than 300 possible diagnoses of mental disorders in the DSM-IV, and determining which one is the most accurate description of the behaviors presented to the clinician can be challenging. The primary reason for the difficulty in formulating clear diagnoses is the problem of comorbidity; that is, many behaviors shown by children are seen in more than one disorder. When more than one disorder exists within the same individual (i.e., not mutually exclusive), they are considered to be comorbid disorders. Comorbidity is the rule rather than the exception in children and youth, occurring in more than half of all cases referred to mental health professionals.

2.2. Behaviors, Symptoms, Syndromes, and Disorders

Children’s emotional and behavioral problems typically are first noticed by parents or teachers, who may refer these children to a physician, a psychologist, or other mental health professional. Symptoms are behaviors of clinical significance that interfere with functioning. When behaviors occur together to form distinct patterns, they are termed ‘‘syndromes.’’ When syndromes occur with such intensity, frequency, or duration that personal, social, or academic performance is affected negatively, the children may be given a diagnosis of a mental disorder by a psychologist or physician.

As an example, consider the case of ‘‘Eric,’’ a 6-year-old boy in the first grade. As a preschooler, Eric exhibited some behaviors of concern such as high activity level, impulsiveness, and noncompliance with parents’ requests in and out of the home. However, the parents were able to manage these behaviors successfully, and they did not view them as problematic. In school, Eric was required to participate in groups, take turns, and follow directions. Instead of these prosocial behaviors, a pattern of noncompliance, difficulties in participating and cooperating, blurting out answers, talking without permission, and interfering with other children developed. These behaviors were considered symptoms of a problem. When the symptoms occurred together in an identifiable pattern, they comprised a syndrome that was of clinical and educational significance because it interfered with the performance of Eric and others. He was evaluated by a psychologist, who considered the behaviors/syndrome in light of current diagnostic criteria and assigned a diagnosis of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)–combined type. In this example, individual behaviors became symptoms that occurred together to become a pattern (syndrome). Because the syndrome was determined to be at a clinically significant level of impairment, a formal diagnosis of a mental disorder of ADHD was given.

TABLE I Characteristics of Anxiety in Children

TABLE I Characteristics of Anxiety in Children

3. Mental Disorders In Children And Adolescents

The majority of mental disorders listed in the DSM-IV can be seen in children and adults. The concepts of internalizing and externalizing patterns are applicable because most of the disorders can be described in those terms. There are some disorders, however, that are considered to be applicable specifically to children and adolescents, for example, separation anxiety disorder (SAD) and CD.

3.1. Internalizing Disorders

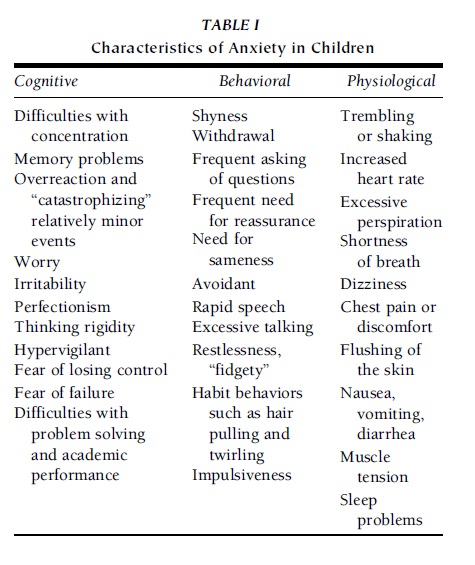

The most common internalizing disorders in children and adolescents are the same types that are seen in adults, although there may be some differences in symptoms. Internalizing disorders include conditions such as major depressive disorder, dysthymia, and bipolar disorder. Anxiety disorders occur in approximately 5 to 10% of children, and the prevalence of depression is approximately 3 to 5%. Table I summarizes characteristics of anxiety problems.

Recent research indicates that bipolar disorder may be more common in children and adolescents than was previously believed. Bipolar disorder was formerly known as manic–depressive disorder and shows a range of mood symptoms from high-energy mania to severe incapacitating depression. However, it is less common than anxiety or depression. Another internalizing anxiety disorder is posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which was initially identified in soldiers who experienced extreme combat exposure, which was followed by ‘‘flashbacks’’ of the events, difficulty in sleeping, and generalized anxiety. In children, PTSD symptoms can be seen as a result of experiences such as abuse, divorce, and other traumatic events, although flashbacks are less common in children. The only anxiety disorder unique to childhood is SAD, which is an unwillingness to separate from parents at a level inappropriate for the age or developmental level of the children. It is common for children to show some anxiety about leaving their parents, even during the early days of school. When the behaviors exceed what is expected developmentally and the children cannot separate in a manner typical of most children, SAD may be an appropriate diagnosis. The presence of SAD may indicate parent–child or family issues; for example, a parent may have difficulty in allowing a child to have increased independence and may encourage and reinforce the child for refusing to separate. A similar pattern may exist in cases where a child exhibits ‘‘school refusal’’ (sometimes referred to as ‘‘school phobia’’). If there is no rational basis for a child to not want to go to school (e.g., being the victim of bullying), it may suggest parent–child or family problems.

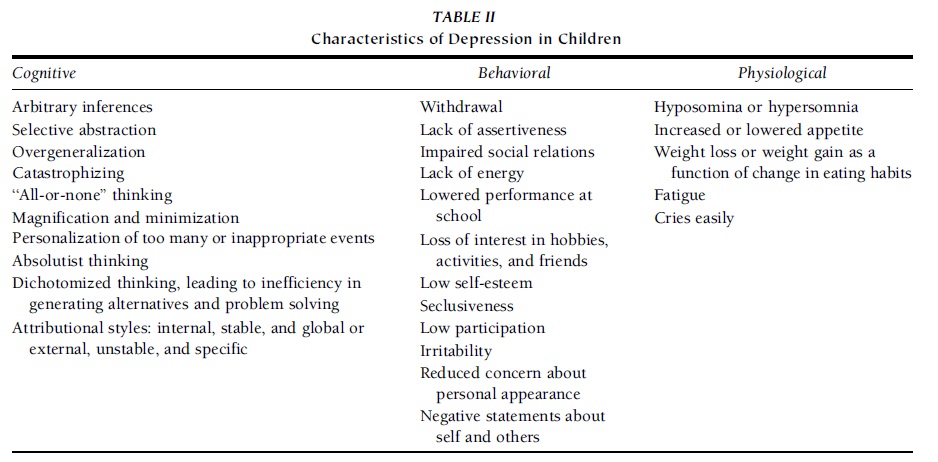

Depression occurs in less than 1% of preschool children and increases during the school years from approximately 0.3 to 2.5% in prepubertal children. By adolescence, however, the incidence of depression increases to approximately 4.3%, with lifetime prevalence rates of major depressive disorder in adolescents ranging from approximately 8.3 to 18.5%. Clearly, depression is a major concern with children and youth and is associated with suicidal ideation and attempts. Depression is a leading cause of death in adolescents after accidents. Some of the major characteristics of depression are presented in Table II.

3.2. Social Correlates of Internalizing Patterns

Children who have internalizing patterns, such as anxiety and depression, may tend to withdraw from social interactions as a way in which to cope with chronic feelings of distress. Withdrawal, social ineptness, and avoidance of interactions due to low self-esteem may be evident. These children may be perceived as ‘‘lazy’’ and unmotivated, despite the fact that they likely want to have social relations but are uncomfortable in initiating interactions due to perceived incompetence and lack of social skills. There is some evidence that anxious and withdrawn children are at higher risk for being the victims of bullies at school and may demonstrate reactive behaviors such as school refusal, sleeping problems, inconsistent performance, lack of assertiveness, poor peer relationships, low self-esteem, and low self-efficacy.

3.3. Academic Correlates of Internalizing Behaviors

Children who show anxiety and depression tend to have academic problems that can lead to more distress, causing a cycle of problems that persist over time. These children tend to avoid academically challenging tasks, withdraw from classroom activities, have poor achievement, lack persistence on difficult tasks, and show signs of ‘‘learned helplessness.’’ They also tend to worry about appearing academically inferior to others, worry about incompetence, do not use effective learning strategies, and blame themselves for academic failure.

TABLE II Characteristics of Depression in Children

TABLE II Characteristics of Depression in Children

TABLE III Symptoms of ADHD

TABLE III Symptoms of ADHD

3.4. Externalizing Disorders

The most common externalizing disorders in children and adolescents are ADHD, CD, and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD). Collectively, these disorders often are referred to as disruptive behavior disorders (DBDs) because they have the common characteristic of showing disruption in home, school, and other settings.

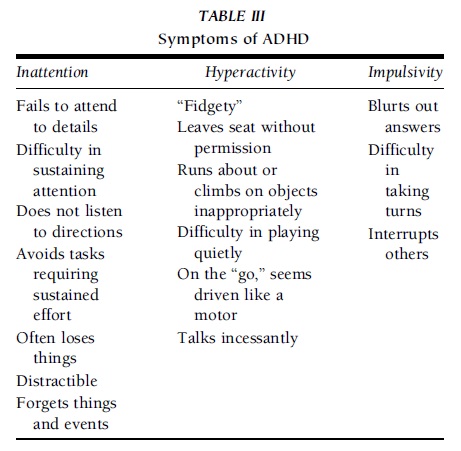

ADHD is the most common DBD and accounts for a large percentage of referrals to mental health professionals. It is shown in approximately 3 to 5% of children and is three to six times more common in boys than in girls. It is a developmental disorder that appears to have some neurological substrates present at birth. With adequate assessment procedures, approximately 50% of cases can be identified by 4 years of age, although many children, especially those who tend to be inattentive, might not be identified until they enter school. There are three subtypes: predominantly inattentive type, predominantly hyperactive–impulsive type, and combined type. The inattentive type tends to be more common in girls than in boys and is more likely to be noticed at home and in situations where high degrees of attention are needed such as in studying, reading, and following directions. The hyperactive–impulsive type is characterized by displaying impulsive behaviors, engaging in off-task behaviors at school compared with peers, acting ‘‘fidgety,’’ making noises, bothering others, and engaging in similar types of behavior. A list of DSM-IV criteria for ADHD subtypes is presented in Table III.

ODD is characterized by a pattern of oppositional behaviors such as noncompliance with requests or directives of parents, teachers, and/or other adults. Most of these children are resistant and defiant to authority and may engage in disruptive behavior but do not demonstrate significant antisocial behaviors. However, boys and girls with ODD are at high risk for developing more serious problems, primarily CD. CD is a well-established pattern of oppositional and defiant behaviors and is accompanied by antisocial behaviors such as stealing, fighting, truancy, and bullying. There are two forms of the disorder: (a) early-onset CD, which occurs before 7 years of age, and (b) late-onset CD, which is first seen during the preteen or early teen years. As might be expected, children with early-onset CD tend to have more serious problems, are more likely to get into trouble with adults who attempt to exercise authority over them, or come into conflict with legal authorities. If the behaviors in early-onset CD are not corrected by late childhood or early adolescence, the prognosis for positive outcomes is guarded at best. Many children with early-onset CD are at high risk for developing antisocial personality disorder as adults, many of whom come into repeated conflict with society, including a high divorce rate, legal difficulties, alcohol or drug abuse, and employment problems. Children with early-onset CD are at a higher risk for school failure and for dropping out of school before graduation. Adolescents with late onset CD are less likely to engage in significant antisocial behaviors. Instead, they are more prone to behavior problems such as poor academic performance, sexual risk taking, smoking, and noncompliance. Many children who are given a diagnosis of CD have met criteria for ODD at some time in their lives but might not have been given that diagnosis. Although most children with CD have met criteria for ODD, the reverse is less common because many children who present with ODD remain oppositional and do not develop the more significant antisocial behaviors associated with CD. ODD appears to set the pattern for CD by evoking coercive, harsh, and inconsistent parenting behaviors that lead to repeated conflict and management difficulties.

ADHD shows comorbidity with ODD and CD, but the relations are varied. Boys with ADHD are at higher risk for developing CD than are boys without ADHD; this appears to be the result of high comorbidity of ADHD and ODD. In boys, ODD appears to be a precursor to CD, but ADHD is not a precursor to CD. Much less is known about these associations with girls; the associations may or may not be similar to those with boys. ADHD begins during the preschool to early school years and, if accompanied by early-onset CD, leads to more significant behavioral problems through the elementary school years.

3.5. Social Correlates of Disruptive Behavior Disorders

Children with DBDs are at higher risk for developing poor relationships with typical peers and adults, including parents and teachers. Their behaviors tend to be annoying and unacceptable to others, leading to punitive reactions by adults and social rejection and ostracism by peers. If the pattern continues, these children are likely to be seen as ‘‘outsiders’’ to their peer groups and will seek out other children with similar patterns, leading to reinforcement of the behaviors and even greater social alienation.

3.6. Academic Correlates of Disruptive Behavior Disorders

Children with externalizing behavior problems or disorders are more likely to do poorly in school, have academic skill deficits, exhibit frequent off-task behaviors, have poor peer relations in the classroom, and be disruptive to the educational process. They also may show signs of frustration, inferiority, anger, and aggression. Angry and aggressive children appear to have a greater number of fears, concerns, feelings of being victimized by others’ actions and provocations, and beliefs that others have negative attitudes toward them. These feelings distract angry and aggressive children from focusing on academic tasks and acquiring necessary learning skills. Much as with the tendency toward social alienation, children with these behaviors may cause teachers and others to be less willing to help them, thereby creating more avenues for academic failure. Continued failure is likely to occur, creating a cycle of frustration and alienation. These children may, however, show ‘‘bravado’’ by exhibiting confidence in their academic skills while, at the same time, harboring resentment and anger at teachers whom they believe are not interested in helping them and at their peers who reject them. They may project the reasons for failure onto others and show boredom and lack of interest in school-related tasks.

4. Interventions

4.1. Programmatic Interventions

Children who have emotional and behavioral problems might need help at school to assist them in achieving as much as possible. In the 2001 U.S. surgeon general’s report, it was reported that 70% of all mental health services provided to children are delivered in the school setting. In general, there are two avenues for providing interventions in the school setting. The first avenue is through general education such as might be provided by school psychologists, counselors, and social workers. These interventions are based on clinicians’ evaluations of children’s needs and may take the form of individual or group counseling, consultation, or parent involvement.

The other avenue for intervention is determining whether children are eligible for special education services. Public schools in all states are required to have special education programs and services for children whose behaviors interfere with academic performance. These programs and their associated regulations must be consistent with the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which provides assurance that all children who have disabilities are properly identified, assessed, and given appropriate instruction and support. For children with emotional and behavioral problems, IDEA uses the term ‘‘emotional disturbance’’ (ED), which is defined as follows:

(i) The term means a condition exhibiting one or more of the following characteristics over a long period of time and to a marked degree that adversely affects a child’s educational performance:

(a) An inability to learn that cannot be explained by intellectual, sensory, or health factors

(b) An inability to build or maintain satisfactory interpersonal relationships with peers and teachers

(c) Inappropriate types of behavior or feelings under normal circumstances

(d) A general pervasive mood of unhappiness or depression

(e) A tendency to develop physical symptoms or fears associated with personal or school problems

(ii) The term includes schizophrenia. The term does not apply to children who are socially maladjusted unless it is determined that they have an emotional disturbance.

Although not all states are required to adopt this specific definition, many use the same or similar terminology (e.g., ‘‘emotional disability,’’ ‘‘behavior disorder’’). The IDEA definition is problematic, however, because many of the terms are ambiguous and are not operationalized (e.g., ‘‘inability to learn,’’ ‘‘satisfactory,’’ ‘‘inappropriate,’’ ‘‘normal circumstances’’). The school psychologist is the professional most responsible for assessment of a child suspected of having ED, although the final determination of eligibility for special education services is done by a case conference committee that includes the parents, the school psychologist, a counselor, teachers, specialists, and others.

The child must have a ‘‘condition’’ that contributes to impairment in educational performance, which most often includes both academic and social development. It is important to note that having a formal DSM-IV diagnosis does not ensure that a child will receive special education services. It is not uncommon for parents to bring a diagnosis from a physician or psychologist to school, asking for special education services, only to be told that the child is not exhibiting problems that are interfering with educational performance. In those cases, the child might not be found eligible for services, despite having a formal psychiatric diagnosis. Conversely, a child could be found eligible for services for students with emotional disturbance and not have a formal psychiatric diagnosis.

A particularly enigmatic provision of the IDEA definition is the ‘‘social maladjustment’’ exclusion clause, which indicates that such children might not be found eligible for services. There is no definition of this term, and this can lead to difficulties for school-based professionals. The term, as originally considered, was to apply to children who exhibited delinquent behaviors that were controllable. Many professionals tend to equate ‘‘social maladjustment’’ with externalizing problems and equate ‘‘emotional disturbance’’ with internalizing conditions. This distinction would suggest that children with oppositional and conduct problems and ADHD would not be eligible for services unless there were accompanying internalizing problems that negatively affected performance. Conversely, because social maladjustment is not defined, one could argue that children with either internalizing or externalizing problems are socially maladjusted. Therefore, operationalizing the social maladjustment criterion for purposes of establishing eligibility is problematic. However, children with externalizing behaviors may qualify for special education services under IDEA or for general education accommodations under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act if needed to benefit from their education. They are not automatically excluded from receiving special education services.

If a student is found eligible for special education services for emotional or behavioral problems, an individualized education plan (IEP) is written in collaboration with the parents, school professionals, and the student if appropriate. In the IEP, goals and objectives are written to address the problems that are affecting educational performance. Services may include counseling, behavioral interventions, consultation with teachers, working simultaneously with the parents, and/or other appropriate interventions. The goal of special education services is not to provide comprehensive mental health services but rather to assist the student in performing at an appropriate level and in gaining educational benefit. The content of the IEP specifies what those services will be and how the outcomes will be measured. Counseling services may be provided if they are made a component of the IEP, or they may be included as an additional service under general education.

4.2. Individual Interventions

Individual interventions for students’ emotional and behavioral problems are numerous and cannot be discussed extensively here. In general, research shows that cognitive–behavioral, behavioral, and multisystemic interventions are among the most effective. A brief summary of the major types of interventions and their goals are presented in the following subsections.

4.2.1. Internalizing Patterns

The majority of internalizing problems are seen in anxiety and depression, which have several common characteristics. Cognitive–behavioral therapy techniques focus on the faulty cognitions and attributions and include components such as attribution retraining, self-talk strategies, self-control methods, self-monitoring, and self-reinforcement. For older students with anxiety, progressive muscle relaxation coupled with systematic desensitization techniques have been shown to be effective in reducing the physiological symptoms of anxiety and in lessening phobic behaviors. Children with depression also tend to be socially withdrawn and to derive relatively little enjoyment from their environment. In these cases, activity increase strategies and reinforcement for increased social interactions may be useful adjuncts to cognitively oriented therapies.

4.2.2. Externalizing Patterns

Children with externalizing patterns, particularly those with aggression, hyperactivity, and impulsiveness, are best addressed with behavioral intervention strategies that emphasize providing consequences for behavior, including rewards and negative consequences. Behavioral contracts, reward systems, token economy methods, reinforcement, and punishments often are effective methods for increasing prosocial behavior while decreasing undesirable behaviors. Aggression replacement training is a method that includes both cognitive and behavioral techniques to address aggression problems. Including parents and teachers in behavior management training, behavioral contracts, and reinforcement programs can be effective in helping students to change behavior over settings. If negative consequences are used, they should be used sparingly and coupled with positive reinforcement. Although physical punishment (e.g., spanking) is used by some parents, research indicates that it has only temporary effectiveness, at best, in stopping a behavior and does little toward teaching prosocial behavior. Other strategies include positive behavioral supports, cognitive– behavioral strategies, and multisystemic therapy.

Children and youth with either internalizing or externalizing problems often have difficulty with social interactions, self-control, and self-regulation of their emotions and behaviors. Therefore, teaching social skills, self-control strategies, and anger management techniques using cognitive–behavioral and behavioral techniques often is necessary to help children function more effectively with peers and adults in the school setting.

4.2.3. Medications

Prescribing medications to address emotional and behavioral problems in children and youth is controversial. The majority of psychotropic medications used with children were developed for adults and then adapted to children with dosage adjustments. In general, the research on short and long-term effects of medications with children is sparse. The exception to this pattern is stimulant medications used to treat ADHD and associated symptoms. Historically, stimulants have been used to treat ADHD and been shown to be effective in approximately 70% of cases with few short or long-term side effects. Some of the newer medications to treat ADHD are not stimulants and show promise of being effective as well as of reducing side effects such as sleeping problems. In the author’s experience, parents tend to be reluctant to agree to use medication with their children, whereas school personnel are more likely to advocate its use, particularly for behaviors such as inattention, off-task, and hyperactivity. It is clear from research and clinical practice that medications, when used appropriately, can be effective in helping to address emotional and behavioral problems. Medication is most often prescribed to treat ADHD in children. The research literature demonstrates that medication combined with behavioral, cognitive, and self-management interventions is more effective than medication alone for the treatment of ADHD. Many children with ADHD have concomitant social and academic problems that are not affected directly by medication, thereby requiring behavioral interventions. Medication should be neither advocated nor completely ruled out for all cases; rather, it should be considered with regard to the needs of the individual child. School personnel are in a particularly good position to observe and monitor the effects of medication and can be valuable collaborators with the prescribing physician.

References:

- Achenbach, T. M., Dumenci, L., & Rescorla, L. A. (2002a). Is American student behavior getting worse? Teacher ratings over an 18-year period. School Psychology Review, 31, 428–442.

- Achenbach, T. M., Dumenci, L., & Rescorla, L. A. (2002b). Ten-year comparisons of problems and competencies for national samples of youth: Self, parent, and teacher reports. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 10, 194–203.

- Achenbach, T. M., & Edelbrock, C. (1978). The classification of child psychopathology: A review and analysis of empirical efforts. Psychological Bulletin, 85, 1275–1301.

- Breen, M. J., & Fiedler, C. R. (2003). Behavioral approach to assessment of youth with emotional/behavioral disorders (2nd ed.). Austin, TX: Pro-Ed Publishing.

- Cichetti, D. (1998). The development of depression in children and adolescents. American Psychologist, 53, 221–241.

- March, J. (Ed.). (1995). Anxiety disorders in children and New York: Guilford.

- Sameroff, A. J., Lewis, M., & Miller, S. M. (2002). Handbook of developmental psychopathology (2nd ed.). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

- Stoff, D., Breiling, J., & Maser, J. (Eds.). (1997). Handbook of antisocial behavior. New York: John Wiley.

- Wenar, C., & Kerig, P. (1999). Developmental psychopathology (4th ed.). New York: McGraw–Hill.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.