This sample Volunteer Programs Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

According to the Corporation for National and Community Service (CNCS), 65.4 million Americans reported that they volunteered in 2005 (the latest year for which data are available), almost 30 percent (28.8 percent) of the U.S. population (CNCS 2006). In 2000 the substantial volume of time volunteered by Americans was the equivalent of 9.1 million full-time employees (based on 1,700 hours per year per employee). The total assigned dollar value of volunteer time in that year was 239.2 billion dollars, which grew to an estimated 280 billion dollars in 2005 (Independent Sector 2001).

Volunteering is, of course, not limited to the United States; although variations exist across countries (Salamon and Sokolowski 2001), volunteering has emerged as “an international phenomenon” (Anheir and Salamon 1999). According to Salamon and Sokolowski’s research on volunteering in twenty-four countries (2001), volunteering constitutes 2.5 percent of non-agricultural employment on average. In their study, this percentage ranged from a low of 0.2 percent in Mexico to a high of 8.0 percent in Sweden.

In the past, volunteering was mainly regarded as work or activities contributed to private charitable or religious organizations. However, volunteers have become a crucial resource for various types of organizations not only in the nonprofit sector but also in the public sector. As an example, the 1992, 1990, and 1988 Gallup surveys on volunteering in the United States show that a significant portion of volunteer efforts went to government organizations (Brudney 1999).

Having such a large amount of time directed to volunteer work does not assure that desirable results are attained for host organizations or volunteers, or for the targets of their well-intentioned efforts. Different issues may arise depending on the types of volunteering activities or on the social and organizational context, and even the nation where volunteering occurs. A 2004 survey on volunteering policies and partnerships in the European Union, for example, suggests that volunteer regulations, policies, and laws differ substantially cross-nationally (Van Hal, Meijs, and Steenbergen 2004).

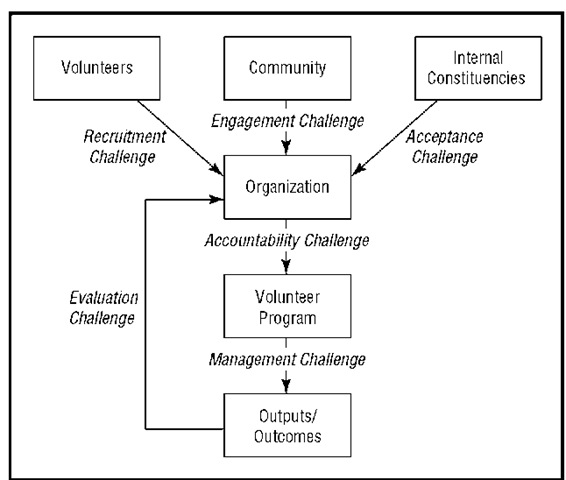

Attaining beneficial outcomes from volunteer involvement for participants, clients, organizations, and the community requires a programmatic structure. Below we explain how to provide this structure for volunteer programs. To do so, we elaborate and extend a model proposed by Young-joo Lee and Jeffrey L. Brudney (2006), based on the essential challenges that all volunteer programs must meet.

Challenges Confronting Volunteer Programs

A volunteer program is a systematic effort to involve volunteers in the work, outputs, and outcomes of an organization. Several authors have proposed models to guide volunteer programs (Boyce 1971; Dolan 1969; Kwarteng et al 1988; Lenihan and Jackson 1984; Penrod 1991; Vineyard 1984). A review of these models shows that they are quite similar, being grounded in a set of core functions that these programs typically perform, such as selection, orientation, and job design. Rather than considering the activities conducted, the challenge model focuses on the goals that must be met to achieve successful performance with volunteers. Although research on the validity of volunteer program design models is scant, a study based on a heterogeneous sample of government volunteer programs suggests that various elements of the challenge model are related empirically to the perceived effectiveness of these programs (Hager and Brudney 2004; Brudney 1999).

Lee and Brudney’s A New Challenge Model of a Volunteer Program (2006), developed originally to guide school volunteer programs, can be extended to the design of volunteer programs in general. These researchers outline six principal challenges that confront volunteer programs:

- recruiting citizens for volunteer service;

- engaging the community in the volunteer program;

- gaining acceptance from organizational members;

- maintaining accountability, to ensure that volunteers adhere to the values and goals of the organization;

- managing the program effectively through structural design;

- evaluating the program’s processes and results.

Figure 1 presents the challenge model of a volunteer program. The article discusses, in turn, each challenge a volunteer program must meet.

Recruiting Citizens Perhaps the greatest challenge to an effective volunteer program is attracting people willing and able to donate their time and expertise. Volunteerism expert Susan Ellis (1996b, pp. 5-6) cautions that “recruitment is not the first step” in a program; a volunteer program must have a clear purpose or goal and meaningful work for volunteers to carry out. Yet, without sufficient volunteers, a program cannot be sustained.

It is important to provide potential volunteers with incentives to participate in the program. A powerful motivation for most volunteers is the idea that their efforts will provide a benefit to the recipients of volunteer service, which in turn will bring them a sense of fulfillment. Most volunteers say that they volunteer to “help other people” or “do something useful” (Brudney 2005, p. 329). Thus, an emphasis on the benefits of a volunteering program would likely prove an effective volunteer recruitment strategy. Another incentive is the benefit to volunteers themselves. Research has shown that there are positive effects of volunteering for volunteers, such as improved health, increased occupational skills, greater networking and social support, and enhanced self-confidence and self-esteem (Wilson and Musick 1999).

A New Challenge Model of a Volunteer Program.

Figure 1. A New Challenge Model of a Volunteer Program.

Figure 1. A New Challenge Model of a Volunteer Program.

The most effective recruitment strategy is to ask people to volunteer. Research findings show that people volunteer far more frequently when they are asked to do so. For instance, the Independent Sector reported that 71.3 percent of the people who volunteered had been asked to volunteer, compared to just 28.7 percent of the non-volunteers (Independent Sector 2002, p. 68). To recruit volunteers, experts recommend targeting groups or organizations with a membership of potential volunteers. For instance, recruitment efforts can be made in workplaces, churches, and synagogues, and directed at neighborhood groups, civic associations, and other institutions in the community (Ellis 1996b).

Engaging the Community As more organizations, including nonprofit, government, and even for-profit, have implemented volunteer programs, an evolution has occurred in the traditional population of volunteers (Smith 1994). Volunteers are no longer predominantly middle-aged, middle-class white women. Instead, they embrace a much wider segment of the community, including males, youth, seniors, people of color, and so forth (CNCS 2006).

A significant consequence of the growth in the number of volunteer programs and an increasingly diverse volunteer pool is that host organizations must compete for volunteers with other nonprofit, government, and corporate volunteer programs. In order to attract volunteers, volunteer programs must emphasize the contribution or impact of a program, its uniqueness, and its connection to the community. Competition also requires volunteer programs to network with other organizations to gain resources and support, such as funding, legitimacy, volunteer opportunities, in-kind contributions, and publicity.

Gaining Acceptance As Brudney (1994) points out, satisfying an organization’s internal constituencies is a prerequisite to setting up an effective volunteer program. Prior to establishing a program, proponents must gain acceptance from, among others, paid staff, board members, clients, and affiliated organizations, such as labor unions and professional associations (if they exist). Without the commitment and support of these stakeholders, the success of a volunteer program is questionable. The likelihood of gaining acceptance increases with the benefits the program may offer, not only to the clients of the program, but also to internal constituencies, volunteers, and the larger community. These benefits can be substantial and include: more attention to clients, greater opportunity for innovation, higher levels of service, increased fund-raising capability, enhanced cost-effectiveness, more satisfying and professional work opportunities, and greater community knowledge, feedback, and involvement (Brudney 2005).

Maintaining Accountability A host organization must make sure volunteers understand the work to be done and the authorized organizational methods and procedures for carrying it out. Accountability makes it possible to recognize and reinforce superior performance by volunteers and, correspondingly, to identify and make changes where performance is inferior or lacking.

In order to ensure accountability, organizational leadership should appoint or hire a volunteer administrator (or coordinator or director) responsible for the overall management and participation of volunteers (Brudney 1996; Ellis 1996, p. 55). The position is usually part-time or constitutes a portion of the duties of a full-time position. Studies find that organizational support for this position is strongly associated with the success of a program (Urban Institute 2004).

Establishing accountability for the volunteer program also includes having a program structure that organizes and integrates the volunteer effort. The program should have job descriptions for volunteer administrators as well as for the volunteer positions to be filled (Brudney 1996). In the United States, the Volunteer Protection Act of1997 (Public Law PL105—119) strongly encourages organizations to have job descriptions for their volunteers. In addition, written policies and procedures should be on file that specify the rules and regulations concerning volunteer involvement, including the rights and responsibilities of volunteers as well as appropriate behavior and norms on the job (for example, confidentiality, reliability, and attire).

Managing the Program As several authors have noted, managing volunteers is not the same as managing employees (Farmer and Fedor 1999; McCurley and Lynch 2006). For example, volunteers are far less dependent on the organization than paid employees and contribute far fewer hours. Given these differences, the volunteer administrator assumes a critical role in the program. Ideally, volunteer administrators should have the following qualifications (Ellis 1996b, p. 60):

- background in volunteerism or volunteer administration;

- ability and/or experience in management;

- proficiency in job design and analysis;

- skills in leadership;

- understanding of the needs of those to be assisted through volunteer effort;

- familiarity with community resources;

- interest in outreach to the community.

The volunteer administrator’s job typically includes recruiting, screening, orienting, training, placing, supervising, evaluating, and recognizing volunteers. This official also has to attend to risk management (Graff 2003). Liability with respect to volunteer programs applies to situations in which a volunteer is harmed while performing his or her duties, as well as when a third party is harmed by a volunteer (Lake 1997). Given the distinctive duties of volunteer administrators, the literature endorses specialized training and preparation for the volunteer administrator position (Ellis 1996b; McCurley and Lynch 2006).

Evaluating the Program Evaluation provides the ultimate justification for a volunteer program. Brudney (1996, p. 201) defines evaluation as “collecting systematic information on the processes and results of the volunteer program and applying these data toward program assessment and, hopefully, program improvement.” To evaluate the effectiveness of volunteer involvement, Brudney recommends focusing on three target audiences: the clients or intended beneficiaries of the volunteer program, internal constituencies, and the volunteers themselves. A variety of methods exist for evaluation of volunteer programs (Gaskin 2003; Goulborne and Embuldeniya 2002).

Of all the challenges, evaluation apparently receives the lowest priority in volunteer programs (Brudney 1999), perhaps as a consequence of the donated nature of volunteer effort. Organizations may be wary of questioning the involvement or effectiveness of citizen volunteers. Nevertheless, just as with any systematic activity, organizations should assess volunteer programs and learn from the results. As Figure 1 shows, the information gained from evaluation should be fed back to the organization and used to improve the volunteer program.

Conclusion

A volunteer program requires an investment on the part of an organization, internal constituencies, and volunteers. Some may ask whether this investment is worth the effort. Indeed it is: Volunteerism benefits all parties involved. Benefits to clients include receiving needed services and the feeling that someone is interested in and cares about them. Benefits to organizations include increasing cost-effectiveness, expanding programs, and raising service quality. Benefits to communities include enhanced civic participation and awareness.

Research has shown that, with respect to the monetary return on investment, volunteer programs routinely yield more in dollar value than organizations expend on them (Gaskin 2003). For clients, volunteers, and communities, the social and psychic benefits are likely to be far greater.

Bibliography:

- Anheier, Helmut K., and Lester M. Salamon. 1999. Volunteering in Cross-National Perspective: Initial Comparisons. Law and Contemporary Problems 62 (4): 43–66.

- Brudney, Jeffrey L. 1994. Volunteers in the Delivery of Public Services: Magnitude, Scope, and Management. In Handbook of Public Personnel Administration, eds. Jack Rabin, Thomas Vocino, W. Bartley Hildreth, and Gerald J. Miller, 661–686. New York: Marcel Decker.

- Brudney, Jeffrey L. 1996. Designing and Implementing Volunteer Programs. In The State of Public Management, eds. Donald F. Kettl and H. Brinton Milward, 193–212. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Brudney, Jeffrey L. 1999. The Effective Use of Volunteers: Best Practices for the Public Sector. Law and Contemporary Problems 62 (4): 219–255.

- Brudney, Jeffrey L. 2005. Designing and Managing Volunteer Programs. In The Jossey-Bass Handbook of Nonprofit Leadership and Management, 2nd ed., eds. Robert Herman et al., 310–344. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Corporation for National and Community Service (CNCS). 2006. Volunteering in America: State Trends and Rankings: A Summary Report. Washington, DC: CNCS.

- Dolan, Robert J. 1969. The Leadership Development Process in Complex Organizations. Raleigh: North Carolina State University.

- Ellis, Susan J. 1996a. From the Top Down: The Executive Role in Volunteer Program Success. Rev. ed. Philadelphia: Energize.

- Ellis, Susan J. 1996b. The Volunteer Recruitment Book (and Membership Development). Philadelphia: Energize.

- Farmer, Steven M., and Donald B. Fedor. 1999. Volunteer Participation and Withdrawal: A Psychological Contract Perspective on the Role of Expectations and Organizational Support. Nonprofit Management and Leadership 9 (4): 349–367.

- Gaskin, Katherine. 2003. VIVA in Europe: A Comparative Study of the Volunteer Investment and Value Audit. Journal of Volunteer Administration 21 (2): 45–48.

- Goulborne, Michele, and Don Embuldeniya. 2002. Assigning Economic Value to Volunteer Activity: Eight Tools for Efficient Program Management. Toronto: Canadian Center for Philanthropy.

- Graff, Linda. 2003. Better Safe: Risk Management in Volunteer Programs and Community Service. Ontario, Canada: Linda Graff and Associates.

- Hager, Mark A. 2004. Volunteer Management Capacity in America’s Charities and Congregations: A Briefing Report. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

- Hager, Mark A., and Jeffrey L. Brudney. 2004. Balancing Act: The Challenges and Benefits of Volunteers. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

- Independent Sector. 2002. Giving and Volunteering in the United States: Findings from a National Survey. Washington, DC: Independent Sector.

- Independent Sector. 2006. Value of Volunteer Time.http://www.independentsector.org/programs/research/volunteer_time.html#value.

- Kwarteng, Joseph A., Keith L. Smith, and Larry E. Miller. 1988. Ohio 4-H Agents’ and Volunteer Leaders’ Perceptions of the Volunteer Leadership Development Program. Journal of the American Association of Teacher Educators in Agriculture 29 (2): 55–62.

- Lake, Jaime. 2001. Screening School Grandparents: Ensuring Continued Safety and Success of School Volunteer Programs. Elder Law Journal 8 (2): 423–431.

- Lee, Young-joo, and Jeffrey L. Brudney. 2006. School-Based Volunteer Programs: Meeting Challenges and Achieving Benefits. The Reporter, Georgia Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Lenihan, Genie O., and Louise Jackson. 1984. Social Need, Public Response: The Volunteer Professional Model for Human Services Agencies and Counselors. Personnel and Guidance Journal 62 (5): 285–289.

- McCurley, Steve, and Rick Lynch. 2006. Volunteer Management: Mobilizing All the Resources of the Community. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Energize.

- Penrod, Kathryn M. 1991. Leadership Involving Volunteers: The L-O-O-P Model. Journal of Extension 29 (4): 3–9.

- Salamon, Lester M., and S. Wojciech Sokolowski. 2001. Volunteering in Cross-National Perspective: Evidence from Twenty-Four Countries. Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project Working Paper no. 40. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Center for Civil Society Studies.

- Smith, David H. 1994. Determinants of Voluntary Association Participation and Volunteering: A Literature Review. Nonprofit Voluntary Sector Quarterly 21: 243–263.

- Van Hal, Tirza, Lucas Meijs, and Marijke Steenbergen. 2004. Volunteering and Participation on the Agenda: Survey on Volunteering Policy and Partnerships in the European Union. Utrecht, Netherlands: CIVIQ.

- Vineyard, Sue. 1984. Recruiting and Retaining Volunteers …No Gimmicks, No Gags! Journal of Volunteer Administration 2 (3): 23–28.

- Wilson, John, and Marc A. Musick. 1999. The Effects of Volunteering on the Volunteer. Law and Contemporary Problems 62 (4): 141–168.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.