This sample Cheating in Sport Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

Recent research reveals that understanding the achievement goal of a person may help to explain cheating in sport. Achievement goals have dispositional elements as well as situational determinants, and both have been associated with cheating and moral action in sport. The more ego involved the person, the more the person cheats. Reducing cheating may be achieved through coach education and by deemphasizing normative comparisons.

Outline

- Introduction

- The Context of Sport

- What Is Cheating?

- The Motivation to Cheat: Achievement Goals as a Determinant of Moral Action

- Dispositional Achievement Goals

- Perceived Motivational Climate and Determinants of Cheating

- What Can We Do about Cheating?

1. Introduction

Cheating in sports is endemic. Each week brings new revelations about cheating, from sprinters who take banned substances (e.g., Dwain Chambers, Carl Lewis, Kelly White) to endurance athletes who take performance-enhancing drugs (e.g., Roberta Jacobs, Richard Virenque, Pamela Chepchumba). But cheating is not limited to individual athletes; prestigious sport organizations have also been caught trying to bend the rules for their own advantage. Some of the most blatant examples of recent cases include the following. Six athletes from the Finnish Ski Federation were discovered to have taken performance-enhancing drugs with the blessing of the medical staff and were disqualified at the Lahti World Cup in 2001. The South Africa, Pakistan, and India cricket teams were found to have fixed matches in 2000. The Welsh Rugby Association recruited illegal players to play for Wales in 2000 by ‘‘discovering’’ fictitious Welsh grandparents for the players. Cyclists on sponsored teams (e.g., the Festina cycling team) in the Tour de France were caught using banned substances in 2001 and 2002. Cheating has even polluted children’s sports, with the most recent visible case being that of Little League pitcher Danny Almonte, who was 14 years of age when he was the winning pitcher for the Little League World Series (restricted to children 9–12 years of age) in 2001. Danny’s father has been indicted for the fraud.

At the time of this writing, a huge cheating scandal involving track and field athletes was breaking in the United States. On October 16, 2003, the U.S. AntiDoping Agency (USADA) released a statement describing the discovery of a new ‘‘designer steroid’’ that had been deliberately manufactured by BALCO laboratories in the United States to avoid detection by current testing procedures. The new steroid (tetrahydrogestrinone or THG) was discovered only after a prominent coach sent a syringe containing the substance to the USADA and named several prominent athletes who were using the steroid. The anti-doping laboratory at the University of California, Los Angeles, identified and developed a test for the substance, and the USADA retrospectively tested the samples from the U.S. Outdoor Track and Field Championships in 2003. Several positive sample results have emerged, and it has been decided that all of the samples from the 2003 World Championships in Paris are to be tested. Terry Madden, the USADA chief executive, stated that this is a case of intentional doping of the ‘‘worst sort’’ and that it involved a conspiracy involving chemists, coaches, and athletes in a deliberate attempt to defraud fellow competitors and the world public. The testing of both ‘‘A’’ samples and, if positive, subsequent ‘‘B’’ samples was ongoing at the time of this writing. In addition, Victor Conte, the founder of the BALCO laboratory that is at the heart of the scandal, was indicted to appear before a grand jury investigating the illegal distribution of a controlled substance. The scandal could involve many athletes and will tarnish many reputations and the sport. Among the athletes named thus far are U.S. shot put champion Kevin Roth, hammer thrower John McEwan, women’s hammer throw champion Melissa Price, and middle distance runner Regina Jacobs, who all tested positive at the 2003 U.S. championships. The European sprint champion, the United Kingdom’s Dwain Chambers, has also tested positive. Among other ‘‘clients’’ of BALCO laboratories who have been implicated are sprinters Marion Jones and Tim Montgomery, baseball star Barry Bonds, and the NFL’s Bill Romanowski.

Not all cheating is as obvious. Each sport has its own manifestation of illegal or inappropriate activity. As an example, professional soccer has what is termed the ‘‘professional foul’’ where players will sometimes pull an opponent’s shirt to prevent or hinder progress with the ball. This is now so common that referees do not call it unless it is very blatant. Football players also ‘‘dive’’ when challenged for the ball, trying to draw a penalty. Baseball players cork their bats. The world’s number one golfer, Tiger Woods, has accused many of his fellow professionals of using illegal drivers that give a ‘‘trampoline effect’’ to the ball. Cricket players tamper with the ball to make it ‘‘swing’’ more through the air. And so on, Why do people cheat in sport? Many explanations have been given, and they are mainly economic (the rewards of being a successful elite athlete are huge), sociological (a breakdown in the moral fabric of society), and psychological (the focus of the current research paper). However, it is the act of competing that has been indicated the most. It is argued that competition, whether on the sport field, in the classroom, or in the boardroom, is the culprit. When people compete, especially in important contexts, people will cheat to achieve success. When winning is everything, they will do anything to win. But so many people who compete do not cheat, so it might not be competition per se that is the problem. An interesting question may then be asked: What are the determinants of cheating, and how are these manifested in sport contexts? The current authors’ research over the past few years has investigated this issue and, like so many other researchers investigating cheating in sport, has looked at children’s sport. What are some of the determinants of children engaging in inappropriate behavior in sport? First, one must look at the context of sport, and what it means for children, and then define what is meant by ‘‘cheating’’ before discussing the manifestation of cheating in sport.

2. The Context Of Sport

Performance in sport is clearly important for adult athletes; the rewards of competence can be significant. In addition, public interest in sport is high and is reflected in the column inches devoted to sport in the popular newspapers as well as in television airtime. It was estimated that one in four persons worldwide watched the final World Cup soccer match between Brazil and Germany on television in 2002. Thus, the entertainment value of sport is increasing for adults. The context is also important to children for different reasons.

Performing in sport contexts is assumed to be important in the socialization process of children toward the development of appropriate moral behavior. In play, games, and sport, children are brought into contact with social order and the values inherent in society and are provided a context within which desirable social behavior is developed. The psychosocial and moral development of young participants is fostered when peer status, peer acceptance, and self-worth can be established and developed, and the adoption of various perspectives is enhanced. Sport is also assumed to provide a vehicle for learning to cooperate with teammates, negotiate and offer solutions to moral conflicts, develop self-control, display courage, and learn virtues such as fairness, team loyalty, persistence, and teamwork. Despite popular beliefs that sport builds character, this notion has been questioned. Research has shown that competition may promote antisocial behavior and reduce prosocial behavior.

The context of sports is becoming an increasingly important one for modern-day children. With the demise of children’s game-playing culture, children are more and more likely to be involved with adult organized sport competition, even as young as 4 years of age (e.g., motocross in Belgium). In addition, research has demonstrated that the domain of competitive sport is a particularly important context for psychosocial development in that peer status, peer acceptance, and self-worth are established and developed. These social attributes are based on many factors, but one way in which a child can gain peer acceptance and status is to demonstrate competence in an activity valued by other children. One area of competence that is highly valued by children is sporting ability. In fact, because of the modern-day visibility of sport, being a good sport player appears to be a strong social asset for a child, especially in the case of boys. Thus, the context is an important one and is one where cheating to gain advantage or gain acceptance with one’s peers can take place.

3. What Is Cheating?

In the area of sport moral action, especially with children, many variables have been investigated. Not all of them may be defined as cheating per se. For example, moral atmosphere has been included and refers to the cultural norms developed within a team about whether cheating is condoned or not. However, all of the variables may be defined as inappropriate behavior, at the very least, and range from poor ‘‘sportspersonship’’ to outright aggression so as to achieve a competitive advantage. Because cheating is a difficult concept to pinpoint and define universally, it may be helpful to view cheating as a product or combination of several more or less moral concepts that are referred to often in the sport psychology literature. For example, cheating in sport has been viewed as a quest to provide an unfair advantage over the opponent. According to this definition, a number of concepts fall into the category of cheating in sport, for example, unsportspersonlike aggressive behavior, inappropriate moral functioning, and a team moral atmosphere where cheating is condoned. Of all the virtues that sport supposedly fosters, sportspersonship is perhaps the most frequently cited. The virtue of sportspersonship is oriented toward maximizing the enjoyable experience of all participants. Although most people believe that they know what sportspersonship is, the development and understanding of the concept has suffered from the lack of a precise definition and an overreliance on broad theoretical approaches. In essence, a sport participant manifests sportspersonship when he or she tries to play well and strive for victory, avoids taking an unfair advantage over the opponent, and reacts graciously following either victory or defeat.

In an effort to generate a much-needed conceptual base to promote research, recent work from Vallerand and colleagues has contributed to a better understanding of the sportspersonship concept. Vallerand has adopted a social psychological view of sportspersonship that separates the latter from aggression and assumes a multidimensional definition consisting of five clear and practical dimensions: full commitment toward sport participation, respect for social conventions, respect and concern for the rules and officials, true respect and concern for the opponent, and negative approach toward sportspersonship. This definition and instrument has been used in sport to investigate sportspersonship. Research has used the scale; however, the negative dimension has never really worked out and is frequently not included. Therefore, when children respect the social conventions (e.g., shaking hands after a game), respect the rules and officials (e.g., not violating the rules or arguing with the referee), and respect the opponent (e.g., helping an opposing player up from the ground in football), they are considered to be high in sportspersonship.

Sportspersonship is but one dimension of social moral functioning in sport, and one model used to more fully investigate the issue is a model suggested by Rest in 1984. Rest proposed a four-component interactive model of sociomoral action that seems well suited when examining sociomoral aspects in sport. The first component of the model deals with interpreting the sport situation by recognizing possible courses of moral action. The second component encompasses forming a moral judgment involving judgments about both the social legitimacy and moral legitimacy of inappropriate sport behavior. The third component involves deciding what one intends to do as a solution to the dilemma, and the fourth involves executing and implementing one’s intended behavior. Behavior might include incidences of nonmoral actions (e.g., aggression) as well as sportspersonship behavior. The process of making a moral decision may be influenced by many factors, including motivational factors, whereas actual behavior may be affected by distraction, fatigue, and factors that physically prevent someone from carrying out a plan of action. The interactive nature of the four processes means that factors proposed to act primarily on one process also influence the others indirectly. As an example, when a child is in a competitive context, many kinds of behavior are possible, including whether to cheat or not. A situation may develop where one could cheat to stop a player from scoring, but is it appropriate to do so? If doing so is judged as appropriate, does one intend to cheat to stop the player from scoring? Finally, does one actually cheat to stop the player from scoring? In this way, players go through the components of Rest’s model.

In 1985, Shields and Bredemeier argued that a major factor influencing the construction of a moral judgment, and consequently moral behavior, in sport is the moral atmosphere of the team. To capture the perceived judgments by significant others as either approving or disapproving of one’s moral actions, research has often included how the players perceived the moral atmosphere in terms of social moral team norms. Sport teams, like all groups, develop a moral atmosphere composed of collective norms that help to shape the moral actions of each group member. An example again is the professional foul in soccer. Sociomoral atmosphere, or perceived sociomoral team norms, has been measured by means of a questionnaire.

Another variable has been the perceived legitimacy of intentionally injurious acts. Participants are asked to imagine themselves competing in an important competitive context. Various intentionally injurious acts are described, and participants are asked to indicate to what degree they agree or disagree with the legitimacy of the actions described.

This is how moral functioning and cheating have been defined in research in sport, especially with children. But why do people cheat? One avenue for exploring this issue has been to look at the motivation to cheat and has used concepts from motivation theory and research. The basic arguments behind this line of research are considered next.

4. The Motivation To Cheat: Achievement Goals As A Determinant Of Moral Action

The most promising avenue to investigate moral functioning and action in sport has been to use achievement goal theory. This framework assumes that achievement goals govern achievement beliefs and guide subsequent decision making and behavior in achievement contexts. It is argued that to understand the motivation of individuals, the function and meaning of the achievement behavior to the individual must be taken into account and the goal of action must be understood. It is clear that there may be multiple goals of action rather than just one. Thus, variation of behavior might not be the manifestation of high or low motivation per se; instead, it might be the expression of different perceptions of appropriate goals. An individual’s investment of personal resources, such as effort, talent, and time in an activity as well as moral action, may be dependent on the achievement goal of the individual in that activity.

The goal of action in achievement goal theory is assumed to be the demonstration of competence. In 1989, Nicholls argued that two conceptions of ability manifest themselves in achievement contexts: an undifferentiated concept of ability (where ability and effort are perceived as the same concept by the individual or he or she chooses not to differentiate) and a differentiated concept of ability (where ability and effort are seen as independent concepts). Nicholls identified achievement behavior using the undifferentiated conception of ability as task involvement and identified achievement behavior using the differentiated conception of ability as ego involvement. The two conceptions of ability have different criteria by which individuals measure success. The goals of action are to meet those criteria by which success is assessed. When task involved, the goal of action is to develop mastery or improvement and the demonstration of ability is self-referenced. Success is realized when mastery or improvement has been attained. The goal of action for an ego-involved individual, on the other hand, is to demonstrate normative ability so as to outperform others. Success is realized when the performance of others is exceeded, especially when little effort is expended.

Whether one is engaged in a state of ego or task involvement is dependent on the dispositional orientation of the individual as well as situational factors. Consider the dispositional aspect first. It is assumed that individuals are predisposed to act in an ego or task-involved manner. These predispositions are called achievement goal orientations. An individual who is task oriented is assumed to become task involved, or chooses to be task involved, so as to assess demonstrated competence in the achievement task. The individual evaluates personal performance to determine whether effort is expended and mastery is achieved; thus, the demonstration of ability is self-referenced and success is realized when mastery or improvement is demonstrated. In contrast, an individual who is ego oriented is assumed to become ego involved in the activity. The individual evaluates personal performance with reference to the performance of others; thus, the demonstration of ability is other-referenced and success is realized when the performance of others is exceeded, especially when little effort is expended.

Achievement goal theory holds that the state of motivational goal involvement that the individual adopts in a given achievement context is a function of both motivational dispositions and situational factors. An individual enters an achievement setting with the disposition tendency to be task and/or ego oriented (goal orientation), but the motivational dynamics of the context will also have a profound influence on the adopted goal of action, especially for children. If the sport context is characterized by a value placed on interpersonal competition and social comparison, the coach emphasizing winning and achieving outcomes, and a public recognition of the demonstration of ability, a performance climate prevails. This reinforces an individual’s likelihood of being ego involved in that context. If, on the other hand, the context is characterized by learning and mastery of skills, trying hard to do one’s best, and the coach using private evaluation of demonstrated ability, a mastery climate prevails. An individual is more likely to be task involved in that context. Therefore, being task or ego involved is the product of an interaction of personal dispositions and the perceived motivational climate. However, in the research literature, investigators typically look at one aspect or the other are rarely look at them in combination. Shields and Bredemeier argued that situational influences may have a great effect on an athlete’s moral action. Competitive ego-involving structures may focus the individual’s attention on the self and, in the case of team sports, on those comprising the in-group as well. This may reduce the player’s sensitivity to the welfare of opposing players. Extensive involvement in competitive contexts may reduce the person’s ability to show empathy, thereby reducing consideration for the needs of others faced with a moral dilemma. Indeed, several studies have shown that participation in competition is associated both with reduced sportspersonship and prosocial behavior and with increased antisocial behavior, hostility, and aggressiveness. However, it is argued here that it might not be competition in and of itself that induces sociomoral dysfunction on the individual and group levels. Rather, it might be the perceived motivational climate that may shape an athlete’s moral functioning. Indeed, moral development theorists, such as Rest, agree that moral behavior is intentional motivated behavior. Thus, to predict sociomoral perceptions and actions, one must consider the motivational characteristics of the situation. First, dispositional influences on cheating are examined.

5. Dispositional Achievement Goals

When looking at the various important personal factors influencing people’s behavior in sport, moral reasoning ability and achievement goal orientations have emerged as significant variables. An early research study found that moral reasoning in the context of sport is much more egocentric than moral reasoning in most situations in everyday life. Athletes, as compared with nonathletes, seem to change their basis for moral reasoning from non-sport to sport-related activities. This type of reasoning seems to focus on self-interest and personal gain. Research has shown that when athletes are task or ego oriented, they differ in various aspects of moral behavior as well as in views regarding what represents acceptable behavior in sport. For example, athletes who are primarily concerned with outperforming others (ego oriented) have been found to display less mature moral reasoning, tend to be low in sportsperson like behavior, approve of cheating to win, and perceive intentionally injurious and aggressive acts in sport as legitimate. In contrast, among task-oriented athletes who tend to use self-referenced criteria to judge competence and feel successful when they have achieved mastery or improvement of the task, greater approval of sportspersonship, disagreement with cheating to win, and less acceptance of intentionally injurious acts have been observed.

Research has found that players who reported higher temptation to play unfairly and greater approval of behavior designed to obtain an unfair advantage were more likely to be ego oriented. These players also perceived their coaches as being more ego involving than task involving. In addition, the athletes believed that teammates would play more unfairly and would have a higher rate of approval of behavior aimed at obtaining an unfair edge over the opponent. In a study investigating the influence of moral atmosphere (i.e., the collective team norms approving of cheating) on the moral reasoning of young female soccer players, players who were in a culture where aggression and unfair play were tolerated were more ego oriented. Furthermore, it has been found that ego-oriented players had lower levels of moral functioning, had greater approval of unsportspersonlike behavior, and judged that intentionally injurious acts are legitimate. Ego orientation has been related to unacceptable achievement strategies such as the use of aggression. Findings indicate that players high in ego orientation display more instrumental aggression than do participants with low ego orientation, suggesting that participants high in ego orientation may adopt a ‘‘win at all costs’’ attitude.

However, ego-involved individuals can also adopt adaptive achievement strategies. It is believed that when individuals are both ego involved and high in perceived ability, so long as the perception of high ability lasts, these individuals will seek challenging tasks, will revel in demonstrating their ability, and generally will not cheat. But when these individuals experience a change in their perception of ability, they are more likely to cheat so as to continue winning. Research has confirmed this in that high ego-, low task oriented participants who are low in perceived ability are more likely to endorse cheating in sport than are high ego-, low task-oriented participants who are high in perceived ability. High task-oriented individuals are less likely to approve of cheating in sport than are any other sport participants, regardless of perceived ability. An athlete high in ego orientation is assumed to believe that winning is the single most important thing when competing. When doubt about one’s own ability exists, this may lead the young athlete to believe that it is harder to contribute to his or her team’s success by using skills alone. The athlete can then be tempted to cheat so as to help the team win and gain peer acceptance. In some of the current authors’ research over the years with young players in soccer, they have found that an ego achievement goal orientation is associated with poor sportspersonship and cheating when perception of ability is low. These findings suggest that young athletes are likely to cheat when they do not believe that they can succeed by simply playing fair. How far one is willing to go to win is often seen as a positive attribute in the world of competitive sport. If one player is willing to get caught or be reprimanded by the officials while trying to intimidate or undermine the opponent, this athlete is likely to generate a positive response from his or her peers, parents, and coaches when playing on a team where winning is everything. Team loyalty can be demonstrated by going against the rules, particularly if the athlete does not get caught. The current authors have found that athletes with a high ego orientation show low respect for rules and officials as well as low respect for opponents.

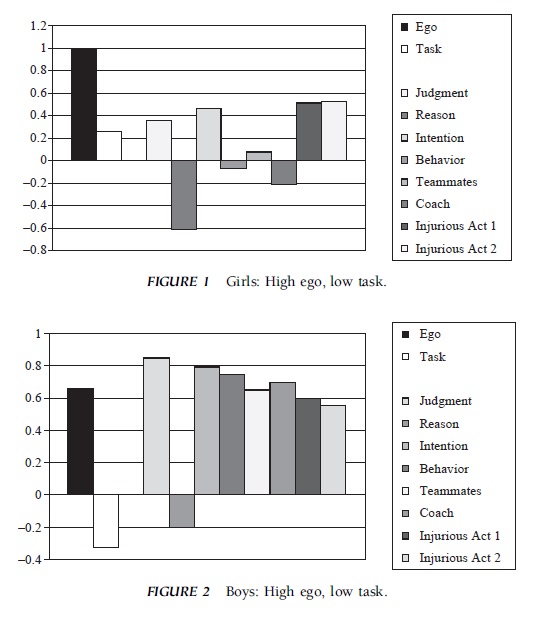

When winning is everything and perception of ability is low, cheating and going against the rules may be judged to be acceptable so as to gain peer acceptance. This is true for both boys and girls. But boys cheat more. To illustrate this, two figures are included showing how boys and girls differ in degree if not in kind. These figures present data from the authors’ own ongoing research involving young soccer players in the Norway Cup, the largest international competition for children in the world. The data show the impact of being high in ego orientation. In this particular example, the authors, using the Rest model to inform their questions, asked the players some questions about their experience with playing soccer. They wanted to see the relationships of the motivational variables on moral reasoning and moral action variables. Figure 1 shows a canonical correlation chart of the responses of high-ego girls (ages 15–16 years). To be meaningful, the correlations should be greater than .30. As can be seen in the figure, when girls are ego involved, they judge inappropriate behavior as being appropriate, and the most important reason was negative; therefore, they were low in moral reasoning, they intended to cheat, and they judged injurious acts as being appropriate to win.

Not attaining significance, these girls had not cheated over the previous five games and considered the team atmosphere and the coaching climate as being relatively neutral. However, they were quite prepared to injure an opponent in the quest to win. Compare this with Fig. 2, which shows a canonical correlation chart of the responses of high-ego boys. These boys judged inappropriate behavior as being appropriate, and the most important reason was clearly negative; therefore, they were low in moral reasoning, and all of the other variables are clearly positive.

This means the high-ego boys admitted that they had cheated over the previous five games, thought that the team atmosphere supported cheating to win, considered the coach as supporting cheating, and were quite prepared to injure opponents in their desire to win. These data show clearly that high-ego players have more tolerance toward and support cheating to win, even to the extent of supporting injurious acts. Although the boys and girls thought and behaved in the same general way, boys are more extreme and do cheat more.

Clearly, being ego or task involved has implications for moral action in sport. The influence that the motivational climate has on moral thinking and action is considered next.

6. Perceived Motivational Climate And Determinants Of Cheating

Similar to the task and ego-involving criteria to which an individual may be disposed, the situational aspects of the competitive environment are also important. Although a number of significant others (e.g., teachers, parents, peers) can and do influence, to some extent, the type of motivational climate that is perceived, the coach is perhaps the most influential facilitator of task or ego-involving criteria for the athlete. The bottom line here is that the criteria of success and failure that the coach brings into the situation are the criteria that the athlete adopts. The younger the athlete, the more likely it is that he or she will pay attention to the criteria of the coach. Indeed, there is evidence indicating that the criteria of what constitutes success and failure for the coach ‘‘washes out’’ the personal criteria of the young player. As such, the achievement goal that the coach imposes on the context becomes an important determinant of the behavior of the athlete.

In discussing the motivational climate, the terms ‘‘performance climate’’ (an ego-involving coach) and ‘‘mastery climate’’ (a task-involving coach) are used. If a performance climate prevails, the coach and the athletes may come to view competition as a process of striving against others. The players may perceive pressure from the coach to perform well or be punished as well as pressure to outplay opponents and win so as to receive recognition and attention. Players may resort to cheating, violating rules, and behaving aggressively as a means of coping. In competition, a performance climate may generate a strong interteam rivalry. A hostile atmosphere toward opposing players may result, leading to the development of team norms or shared social moral perceptions among team members reflecting a derogatory and depersonalized picture of opposing players as mere obstacles to be overcome in the quest for victory by their own team.

The investigation of perceived motivational climate in relation to cheating is a relatively new research area among sport social scientists. The findings thus far indicate that perceived mastery and performance motivational climates created by coaches do affect cheating in systematic ways.

Players perceiving a strong mastery motivational climate reported that sportspersonlike behavior is important in competitive soccer. Players reported that it was important to value and respect the rules of the game and the officials who represented the rule structure. In addition, players noted the importance of respecting the social conventions found within the soccer environment when they perceived the coach as emphasizing mastery motivational criteria. In contrast, it has been shown that players who perceive a high performance climate indicate lower sportspersonship than do players who perceive a high mastery climate.

In general, the majority of research indicates that a perceived performance motivational climate is associated with cheating, whereas a perceived mastery motivational climate is associated with more positive moral actions. This is true for college-level athletes as well as for younger athletes. In brief, perceptions of performance climate criteria were related to a lower level of moral understanding within the team, resulting in lower moral functioning illustrated by means of low moral judgment, a high intention to behave nonmorally, and low self-reported moral behavior.

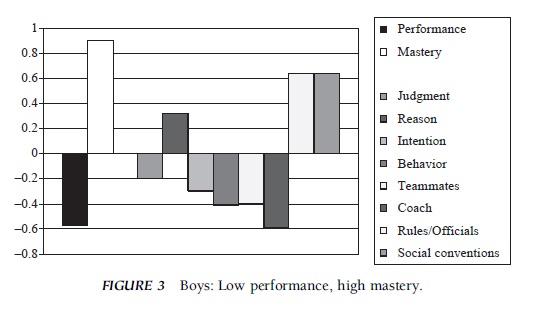

Among high-level collegiate male and female basketball players, it has been found that players perceiving a performance motivational climate perceived a low moral atmosphere within their team that was related to lower moral functioning. Various perceptions of the motivational climate have been shown to be related to differing levels of moral functioning and perceptions of team moral atmosphere. Evidence illustrated in Fig. 3 shows that young players who perceive a strong mastery motivational climate indicated positive sportspersonship (i.e., had respect for opponents and officials and also respected social conventions), had positive moral reasoning, had a low intention to cheat, seldom engaged in cheating behavior, and considered the team norms and the atmosphere created by the coach to be anti-cheating.

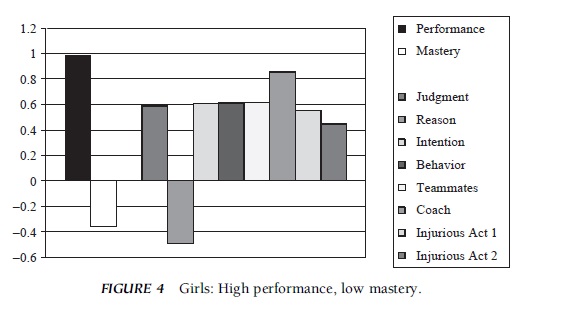

In contrast, Fig. 4 shows a canonical correlation chart of the responses of girls in a performance-oriented climate. When girls are ego involved, they judged inappropriate behavior as being appropriate, and the most important reason was negative; therefore, they were low in moral reasoning, intended to cheat, had cheated during the previous five games, considered that the coach and teammates approved of cheating, and considered injurious acts appropriate to win. Again, the figure illustrates that even girls (and young female youth), when ego involved through a performance climate created by the coach, will increase their cheating.

FIGURE 3 Boys: Low performance, high mastery.

FIGURE 3 Boys: Low performance, high mastery.

FIGURE 4 Girls: High performance, low mastery.

FIGURE 4 Girls: High performance, low mastery.

Gender differences have been found in the motivational climate literature consistently in that young male players react more strongly to performance climate criteria and are more prone to cheating compared with female players: Again, boys cheat more than do girls. However, the important point here is that regardless of gender, a strong coach-created performance motivational climate is related to low moral functioning, inappropriate behavior is judged to be appropriate, and players have lower moral reasoning, have a higher intention to cheat, and actually do cheat more. In addition, both male and female players identified their team moral atmosphere to be more supportive of cheating. These data show clearly that when players are ego or task involved, they think differently, have different ideas about cheating, and report different episodes of intention to cheat and actual cheating. Ego-involved players have more tolerance toward and support cheating to win, even to the extent of supporting injurious acts.

The research findings are quite consistent. When the coach emphasizes criteria of success and failure showing that he or she values winning above all else, athletes indicate that they tolerate cheating more and actually do cheat more than athletes who perceive their coach as emphasizing more mastery criteria of success and failure. This is true for elite athletes, at the professional and Olympic levels, as well as for child and youth sport participants. Clearly, the coach matters, but the major point here is that the coach does not have to endorse cheating per se; rather, it is simply that the coach who emphasizes winning above all else creates a motivational climate that the athletes interpret as being more accepting of cheating behavior.

7. What Can We Do About Cheating?

Some people deliberately cheat. There are enough cases in sport, in corporate business, and in everyday life demonstrating that some individuals and organizations simply cheat to gain an unfair advantage. There is little that can be done about these systematic cheats except to try to catch and punish them to the full extent possible. Whether that is through drug testing in sport, financial oversight in corporate business, and so on, regulations and oversight are needed to cull out the cheats. But cheating can be much more subtle and unintentional in many cases. It is this latter form of cheating that is addressed in these final remarks.

Competitive sport often places people in conflicting situations, where winning is emphasized and where fair play and justice are sometimes deemphasized. It would be wrong to attribute this to the competitive nature of sport. The research reported in this research paper suggests that the culprit is not competition in and of itself. Rather, the culprit may be the difference in salience of ego and task-involving cues in the environment, whether through one’s own disposition or through the cues emphasized by one’s coach (or parent). It is these perceived criteria of success and failure that induce differential concern for moral action and cheating. A focus on winning may reinforce prejudice (i.e., ‘‘us against them’’) and lead to a more depersonalized view of opponents that, in turn, makes cheating more possible.

How can the development of good sportspersonship and sound moral reasoning be maximized, and how can cheating be prevented? Clearly, one way in which to help is to teach the coach to reinforce the importance of task-involving achievement criteria in the competitive environment. This is important at all levels, especially in light of the degree of cheating going on in professional and Olympic sports. But this is more important for children’s and youth sports. This does not mean that one cannot strive to win; rather, it means that we should apply different criteria to the meaning of winning and losing. By giving feedback to players on effort, hard work, and self-referenced increments in competence, more respect for rules, conventions, officials, opponents, and appropriate moral reasoning and action could be cultivated. One way in which to say this is that there are no problem athletes, just problem coaches (and parents). Coaches must be aware of the criteria of success and failure that they are emphasizing. If task involving criteria are emphasized, cheating can be reduced and moral reasoning and action can be enhanced.

When focusing on children in the competitive sport experience, it is not just the coach who needs to be aware of the criteria being emphasized; parents are the most important source of information for the children. Indeed, it is often the parents who are most to blame in children’s sports. However, coaching programs that address both parents and coaches now exist in most countries. The evidence is accumulating that strategies and instructional practices should be developed to facilitate the coach (and parents) in creating a task involving coaching environment that is concerned with mastery criteria of success and failure. If there is concern about optimizing the motivation, psychosocial development, and moral functioning and action of children, the impact that teaching and coaching style have on these outcomes cannot be ignored.

However, coaches must realize that simply trying to enhance mastery criteria is often not enough. The ego-involving criteria are emphasized as well. Normative evaluation should not be used for athletes. Comparisons should be made with children’s own past performance rather than with the performance of their peers. By giving feedback based on their own past performance and trying to give feedback to athletes privately rather than in an announcement to the whole team, coaches can do their best to maintain the motivation of the athletes and remove an important determinant of cheating in sport.

Will cheating ever be eliminated from sport? That is unlikely in elite sport when the rewards are so high. But in children’s sport, attempting to reduce cheating is critical. Playing fair and recognizing justice for all should be a natural part of the sport experience. If the sport experience is the context in which children learn to relate to their peers, not only in sport but also for life, the criteria of success and failure inherent in the sport experience should be a critical concern.

References:

- Dunn, J. G. H., & Dunn, J. C. (1999). Goal orientations, perception of aggression, and sportsmanship in elite male youth ice hockey players. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 13, 183–200.

- Kohn, A. (1986). No contest: The case against competition. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Nicholls, J. G. (1989). The competitive ethos and democratic education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Ommundsen, Y., Roberts, G. C., Lemyre, P. N., & Treasure, D. (2003). Perceived motivational climate in male youth soccer: Relations to social–moral functioning, sportspersonship, and team norm perceptions. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 4, 397–414.

- Rest, J. R. (1984). The major components of morality. In W. Kurtines, & J. Gewirtz (Eds.), Morality, moral behaviour, and moral functioning (pp. 356–429). New York: John Wiley.

- Roberts, G. C. (2001). Understanding the dynamics of motivation in physical activity: The influence of achievement goals on motivational processes. In G. C. Roberts (Ed.), Advances in motivation in sport and exercise (pp. 1–50). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Shields, D. L., & Bredemeier, B. J. L. (1995). Character development and physical activity. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Vallerand, R., & Losier, G. F. (1994). Self-determined motivation and sportsmanship orientations: An assessment of their temporal relationship. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 16, 229–245.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.