This sample Zoocentrism Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality paper on argumentative research paper topics at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

Zoocentrism can include an array of bioethical theories that share the assumption that at least some animals have moral standing per se. It emerged from the social justice movement in the late eighteenth century, resulting in the foundation of the animal protection movements throughout the nineteenth century. Societal concern for the treatment of animals, especially in agriculture and research, in the last quarter of the twentieth century catalyzed the further development of zoocentric philosophy, most notably Singer’s advocacy of treating equal interests equally, Regan’s animal rights doctrine, virtue-based approaches, and Rollin’s hybrid ethical viewpoints. Key outcomes of zoocentrism are evident in societal attitudes towards animals, particularly in Western societies, with the development of legal frameworks, which not only aim to prevent cruelty to animals but also to support the health and well-being of animals in agriculture, research, sport, and companionship.

Introduction

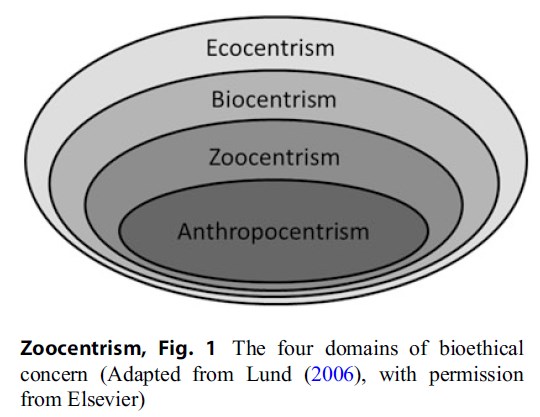

The interactions that humans establish with other humans, animals, and nature are complex and diverse and probably reflect different types of moral concern. With regard to who, or what, is included as a member of the bioethical community, four domains are usually considered: anthropocentrism, zoocentrism, biocentrism, and ecocentrism. These domains represent an expanding circle of bioethical inclusiveness, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Anthropocentrism considers that human beings only are morally relevant, zoocentrism includes other animals in the moral sphere alongside humans, and biocentrism confers moral standing to all living beings (i.e., the biota), while ecocentrism expands moral concern to include all of nature, living and nonliving (i.e., the ecosphere).

Figure 1 The four domains of bioethical concern (Adapted from Lund (2006), with permission from Elsevier)

Figure 1 The four domains of bioethical concern (Adapted from Lund (2006), with permission from Elsevier)

Conceptual Clarification And Definitions

Zoocentrism refers to ethical theories that confer moral standing towards at least some animals. The adjective “zoocentric” was probably first recorded in 1882 in the Transactions of the Anthropological Society of Washington:

Until within quite a recent period all philosophy was strictly anthropocentric, and the lower grades of creatures capable of enjoyment and suffering were wholly ignored; but in later times a few of this school have expanded their scheme to embrace the animal world in general, rendering it zoo¨centric instead of anthropocentric (.. .) (Forty-Eight Regular Meeting, December 20, 1881, p. 93)

Together with zoocentrism, two related terms are also found in the literature and often used interchangeably: pathocentrism and sentientism. Although these three terms relate to the same concept – that at least some animals have moral standing per se – their somewhat different meanings should be noted. Pathocentrism (from the Greek pathos, meaning “suffering”) refers to the moral viewpoint that primarily considers the suffering of animals as morally significant. It is a terminology used mostly in countries with Germanic influence and corresponds, to a great extent, to what is called by others as sentientism (from the Latin sentiens, meaning “feelings” or “perception”), the moral viewpoint that primarily considers the sentience of animals. But while the term sentientism alludes to animals’ capacity of experiencing both positive and negative mental states – or feelings – the term pathocentrism is focused on the negative ones, thus giving an eschewed picture of animals’ sentientistic abilities of moral relevance.

The term sentientism was firstly used by John Rodman in 1977 to refer to Peter Singer’s philosophy as “a kind of zoöcentric sentientism” (Rodman 1977, p. 91), while others have used the same term to describe the moral prejudice that privileges sentient over non-sentient beings and hence should be used carefully. In addition, sentientism fails to describe the range of theories granting moral standing to animals. Zoocentrism, on the other hand, is a broader term that encompasses both sentientism and pathocentrism while including other justifications for conferring moral standing to at least some animals, such as rights and virtue-based ethical theories.

Despite its broad meaning, the term “zoocentrism” has not been widely used and is often superseded by the concept of “animal ethics,” which prominently includes zoocentric ethical viewpoints. One possible reason why the term “zoocentrism” is not in common usage is because its meaning can be misleading. The Oxford English Dictionary defines zoocentric as “centred upon the animal world; regarding or treating the animal kingdom as a central fact.” However, zoocentric philosophies are not necessarily centered upon animals, but work to include animals in the moral community, alongside humans. This is in contrast with “anthropocentric” viewpoints, which are centered on humans and often exclude other entities from the moral community (Fig. 1).

The Emergence Of Zoocentrism

As a philosophical domain, zoocentrism emerged relatively recently. Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832), the founding father of modern utilitarianism, is often credited as one of the first Western philosophers to defend a zoocentric moral stance when, in 1789, he claimed:

The day may come, when the rest of the animal creation may acquire those rights which never could have been withholden from them but by the hand of tyranny. The French have already discovered that the blackness of the skin is no reason why a human being should be abandoned without redress to the caprice of a tormentor. It may come one day to be recognized, that the number of the legs, the villosity of the skin, or the termination of the os sacrum, are reasons equally insufficient for abandoning a sensitive being to the same fate. What else is it that should trace the insuperable line? Is it the faculty of reason, or, perhaps, the faculty of discourse? But a full-grown horse or dog is beyond comparison a more rational, as well as a more conversable animal, than an infant of a day, or a week, or even a month, old. But suppose the case were otherwise, what would it avail? the question is not, Can they reason? nor, Can they talk? but, Can they suffer? (Bentham 1789, ch. XVII, para 4, fn.)

The principle of utility expressed by Bentham – an action is moral if it maximizes happiness and minimizes suffering for all those involved, animals included – contributed to the animal protection movements in the Victorian age and influenced the animal rights’ theories in the last quarter of the twentieth century. While widely cited, it is often not mentioned that this quote is a footnote used to reinforce the argument for abolishing human slavery and placed towards the end of an extensive essay – An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation – where animals are only mentioned three times. Despite his tremendous influence, Bentham is still an anthropocentric philosopher who, although opposed to hunting and baiting, used anthropocentric arguments to justify animal vivisection and the slaughtering of animals for human consumption (Singer 1975, pp. 210–211). Throughout history, other Western thinkers that have expressed zoocentric viewpoints include Voltaire (1694–1778), Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778), Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860), and Charles Darwin (1809–1882), but it is only with the works of animal liberationist philosophers Peter Singer (b.1946) and Tom Regan (b.1938) in the 1970s and 1980s that zoocentrism has come to the fore.

Mainstream Zoocentric Ethical Views

Zoocentrism can include an array of bioethical theories that share the assumption that at least some animals have moral standing per se. Three of the main philosophical viewpoints are briefly presented: utilitarianism, deontological ethics, and virtue ethics, as well as a combination of these perspectives, referred to as the hybrid view. These normative theories are at the origins of two mainstream contemporary animal protection movements: animal welfare and animal rights, which will be later explained.

Utilitarianism

Peter Singer’s groundbreaking book Animal Liberation (1975) applied the utilitarian philosophy to the ethical treatment of animals. Singer considers sentience to be the fundamental morally relevant criterion for having interests. According to the principle of equality, the interests of all sentient animals – human or nonhuman – deserve equal consideration. Failing to do so with regard to sentient animals is speciesist, a form of prejudice based solely on species membership. The term speciesism was coined by English psychologist Richard Ryder (b.1940) in 1970, when advocating against the use of animals in experiments (Ryder 2010). An action is described as speciesist, and hence morally wrong, if – everything being equal – it favors the human species in detriment of another species. Speciesism is purposively connected with other forms of discrimination, such as sexism and racism. In contrast with Bentham’s hedonistic utilitarianism (which works to maximize net happiness, often at the expense of the individual), Singer’s preference utilitarianism considers equally the interests of all the sentient beings involved:

If a being suffers there can be no moral justification for refusing to take that suffering into consideration. No matter what the nature of the being, the principle of equality requires that its suffering be counted equally with the like suffering – insofar as rough comparisons can be made – of any other being. If a being is not capable of suffering, or of experiencing enjoyment or happiness, there is nothing to be taken into account. (Singer 1975, p. 8)

Other contemporary philosophers who have mostly defended utilitarian ethical views to our treatment to nonhuman animals include the Danish bioethicist Peter Sandøe (e.g., Sandøe et al. 2014).

Deontological Ethics

Contrary to consequentialist theories (such as utilitarianism) deontological theories consider that actions or intentions can be right or wrong regardless of their consequences. Taking Kantian deontology as a model, Tom Regan contends in The Case for Animal Rights (1983) that animals have inherent value and that we owe them direct moral duties. According to Regan, those animals which are subjects-of-a-life are ends in themselves and should not be used as a means to an end. To be considered a subject-of-a-life, an animal has to:

(.. .) have beliefs and desires; perception, memory, and a sense of the future, including their own future, an emotional life together with feelings of pleasure and pain; preference and welfare-interests, the ability to initiate action in pursuit of their desires and goals; a psychological identity over time; and an individual welfare in the sense that their experiential life fares well or ill for them (.. .) (Regan 1983, p. 243)

To have inherent value is a categorical condition, meaning that all who have it – humans or nonhumans – have it equally. Although Regan’s theory extrapolates Kantian ethics to include animals, it also narrows the criteria for being a moral subject, since not many animals seem to meet the abovementioned requirements. In his original writings, Regan draws the line in “mentally normal mammals of a year or more,” but later he extended it to include birds and possibly fish (Regan 2003). At the end, he seems more interested in outlining a theoretical boundary than in finding the precise phylogenetic point where an animal ceases to be a subject-of-a-life.

Other contemporary authors who have defended deontological ethical views to our treatment of nonhuman animals include Italian philosopher Paola Cavalieri (2001) and American animal rights activist and scholar Gary Francione (2000).

Although different in their philosophical rationale, utilitarian and deontological zoocentric frameworks end up defending the same kind of animals: those who, at least, are sentient (since sentience is also a prerequisite for having rights). However, these perspectives have been accused of protecting less than 5 % of animals species known on earth (i.e., mostly vertebrates, and some cephalopods, such as the octopus) while almost ignoring the remaining 95 % for which there is not enough evidence that they are sentient or that, in any other way, they do not meet the requirements for being subjects-of-a-life. This has led some to consider that animal liberation theories “condemn the whole of nonsentient creation, including the lower animals, at best to a much inferior status or … at worst possibly to a status completely beyond the moral pale” (Frey 1979). In addition, there exists increasing evidence that some invertebrates that until recently were believed to be non-sentient, particularly crustaceans and mollusks, may have the potential of experiencing pain and suffering. To include the “less sentient” animals into the moral sphere, we need to resort to aretaic theories that draw the ethical line in the character of the agent rather than relying on morally relevant features of the subject.

Virtue Ethics

Virtue ethics, grounded in Aristotelian perfectionism, sees morality as a pursuit of desirable character traits (or virtues) and avoidance of condemnable character traits (or vices). Virtue ethics is a procedural ethics in which what counts is the motivation of the agent and not prima facie moral rules, as in deontological ethics; for virtue ethicists, the rightness or wrongness of actions and intentions will depend on the circumstances rather than on its consequences, as in utilitarianism (Hursthouse 2006; Abbate 2014). A virtuous agent would not consciously kill an insect in the same way that he or she would not consciously run over a dog because both actions would be considered equally vicious (unless there was a good reason to do so, e.g., if the insect is a malaria-infected mosquito or if the dog is in the middle of a highway and to avoid it would cause an accident). One contemporary author who has defended aretaic (virtue) ethical views to our treatment to nonhuman animals is New Zealand philosopher Rosalind Hursthouse. Hursthouse rejects the concept of “moral status” altogether and considers that an action is right if and only if it is what a virtuous moral agent would do in similar circumstances. With regard to our treatment of nonhuman animals, a virtuous agent would use such character dispositions as benevolence, conscientiousness, generosity, compassion, and justice. Among these, compassion is usually considered one of the most important virtues in animal ethics. For example, a virtuous agent would refrain from eating meat because “one cannot be compassionate while being a party to cruel practice,” such as factory farming (Abbate 2014).

It is often claimed that virtue ethics is intrinsically anthropocentric (as opposed to zoocentric) because it is devoted to human flourishing (i.e., living a good human life). Hursthouse offers a response to this criticism by saying that:

Just as the exercise of virtues such as charity, generosity, justice, and the quasi virtue of friendship, necessarily involves not focusing on oneself and one’s virtue but on the rights, interests and good of other human beings, so the exercise of compassion and the avoidance of a number of vices, involves focusing on the good of the other animals as something worth pursuing, preserving protecting and so on. (Hursthouse 2006, p. 153)

It has also been argued that the virtue/vice vocabulary is inadequate as a zoocentric philosophy. Hursthouse, however, has pointed out that the same could be argued for terms such as “rights,” “duties,” and “obligations” and hence “the problem of traditional human-centeredness is one that every philosopher who wants to change our attitudes toward the other animals and the rest of nature has to face, not one peculiar to virtue ethics.” (Hursthouse 2006, p. 154).

Hybrid View

American philosopher Bernard Rollin provides a hybrid zoocentric ethical view. His philosophy is partially utilitarian (by acknowledging the interests of sentient animals), partially deontological (by accepting that we have direct prima facie duties towards animals and by the idea that humans and domestic animals are bound by implicit contracts), and partially virtue-based (by applying Aristotle’s concepts of telos and philia to our treatment of other animals). Central to Rollin’s ethics is the view that animals have teloi, species-specific “natures” of what is to be that animal (“the ‘pigness’ of the pig, the ‘dogness’ of the dog”) which need to be respected. Something that prevents animals from fulfilling their teloi is wrong (such as raising battery hens), whereas those actions that help animals developing their teloi and flourish are considered to be good (such as raising free range hens). Although Rollin is mostly concerned with how sentient animals are treated and in their ability to express species-specific behaviors, the concept of telos could be transposed to respect the life of other “less sentient” animals, including insects (Rollin 1992, p. 96), which would bring it closer to biocentric ethical viewpoints.

Inspired by elements of moral psychology, Rollin also supports a relational approach to animal ethics. Rollin (2005) defends what he calls a reasonable partiality towards companion animals based on the assumption that human and companion animals are bonded by feelings of love, friendship, and affection (philia). These affective relationships make companion animals deserving of moral priority:

It makes sense (.. .) in increasing moral concern for animals to press for better treatment of companion animals first, because of our special relationship with these animals, and because our relationship with them is not inherently invasive, involving inflicting pain, distress, or death. At this time, we cannot demand that people treat all animals as they would agree they ideally ought to treat animal companions. (Rollin 2005, p. 112)

Zoocentrism, Animal Status, And The Sociozoological Scale

The moral standing conferred on animals seems to depend on their status or their role in society and how humans relate to them. In effect there is a hierarchy, where high-ranking animals are considered to have greater moral worth than those at the bottom. Such linear hierarchies stem from Aristotle’s “Great Chain of Being,” a ladder depicting the social order of all living beings, with humans positioned at the top of the ladder to reflect their dominion over nature and animals and plants with subordinate rankings. Similar constructs are also evident in religious doctrines and were used to justify human exploitation of the natural world. The notion of social structure pervades human society and influences the degree of moral standing conferred on animals. On a simplistic basis, animals may be considered as good or bad, determined by how we relate to them and how they fit into society. Arluke and Sanders (1996) have illustrated this concept in their sociozoological scale. The sociozoological scale assigns animals to four domains: friends, tools, vermin, and demons. Friends and tools are perceived as “good” animals, because they provide some benefit to humans and society and are therefore granted greater moral consideration than “bad” animals. Conversely, vermin and demons represent “bad” animals, those that conflict with their place in society or may cause problems, and are therefore placed at the bottom of the scale. In Western society, companion animals represent our friends and can be treated as surrogate children and members of the family. As a consequence, they receive the greatest level of protection. Animals used in agriculture and research, while not necessarily our friends, fulfill a functional role and are thus considered tools. The benefits provided by tools are rewarded by granting some degree of protection to them. For example, in the European Union, food-producing animals are recognized as sentient beings and minimum standards have been established to support their health and well-being. In contrast, a relatively low level of protection is conferred on “bad” animals, which are situated at the bottom of the hierarchy. Typical examples of vermin are wild rats, perceived as dirty and disease carrying. Demons, on the other hand, play a more threatening role – such as wild animals that can attack and kill humans. The moral standing of an animal is thus determined by their role in society and not the species per se. For example, the status and therefore degree of protection conferred on a rabbit depends on its role, which will differ depending on whether it is a wild rabbit or purposively breed for meat production, research, or companionship. While they belong to the same species – or at least the same genus – these individuals are conferred differing levels of moral concern, according to the type of relationship humans establish with them.

Zoocentrism And The Foundation Of The Animal Protection Movement

Societal rules and legislation mark important benchmarks in the development of the moral standing of animals in society. For example, the first anticruelty law in the English-speaking world was published in Ireland in 1635, prohibiting the customary practice of attaching a plow (and other carriages) to the tail of the horse and the pulling of wool from living sheep. In North America, a Puritan Minister, Nathaniel Ward, originally from England, published “The Body of Liberties” in 1641, which was the first anticruelty law in Massachusetts (DeMello 2012): tyranny or crueltie towards any bruite creature which are usuallie kept for man’s use.

In the late eighteenth century, there was a growing societal awareness and concern over cruelty towards animals, which was often associated with the social justice movement such as abolition of slavery and rights for women. Examples include Bentham’s famous social commentary (“.. .the question is not, Can they reason? nor, Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?”) and Hogarth’s Four Stages of Cruelty, which was motivated by zoocentric concern: “The four stages of cruelty were done in hope of preventing in some degree that cruel treatment of poor animals.. .”

There were unsuccessful attempts in the early nineteenth century in the UK to introduce anticruelty laws. Finally in 1822 “Martin’s Act” was introduced by Richard Martin MP, an Irish Member of Parliament (also known as “Humanity Dick”), to prohibit the ill treatment of cattle. Martin became renowned for lobbying Parliament to enact new laws to protect animals and for the policing of his own Act, resulting in well-publicized court cases on animal cruelty. He was also associated with the foundation of The Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in England (after Royal decree became the RSPCA; 1824). The RSPCA was a catalyst for the establishment of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in New York in 1865 by Henry Bergh. Bergh was also responsible for introducing an animal anticruelty law in New York, banning the maltreatment of animals such as overworking horses. This law became the blueprint for other states and in 1873, “The TwentyEight Hour Law,” the first federal anticruelty law, was introduced in the USA. Bergh also recognized the link between animal protection and social justice. He was a pioneer for children’s rights, at a time when children were considered to be the property of their parents and had no legal standing. In 1877 he established the American Humane Association, with the dual remit of protecting children and animals. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, the animal protection movement was present across Europe, as can be illustrated by the foundation in 1875 of both the Sociedade Protectora dos Animais, in Portugal, and the Svenska Djurskyddsfo¨reningen, in Sweden.

During its evolution, the focus of the animal protection movement changed to reflect societal concerns. For example, as pet keeping became more popular in the nineteenth century, animal protection societies turned their attention to dogs and cats, establishing animal shelters for unwanted pets such as the “Home for Lost and Starving Dogs” established in 1860 in London, which went on to become the Battersea Dogs and Cats Home.

A major fledgling branch of the animal protection movement arose due to public disquiet regarding the experimentation on animals for medical research, resulting in the formation of anti-vivisection societies in the UK in the nineteenth century. Key protagonists such as Frances Power Cobbe (founder of the Society for the Protection of Animals Liable to Vivisection) were also social reformers, campaigning for women’s rights. Lobbying by anti-vivisection groups resulted in the Cruelty to Animals Act (1876), in the UK, the first law to regulate animal experimentation.

Concerns about farm animal welfare arose after the intensification of agricultural practices in the second half of the twentieth century. In particular, Ruth Harrison’s book Animal Machines (1964) raised public awareness on the welfare problems of intensive livestock production. It sparked a series of events leading to the Brambell Report (1965), which in turn led in the development of the Farm Animal Welfare Council’s “Five Freedoms” and regulatory reform. The focus of regulations on farm animal welfare in Europe and other countries has evolved to reflect scientific evidence on animals’ needs and societal concern. As an ethical framework, the Five Freedoms remain valid to the present day and have been applied to a number of animal sectors.

Zoocentrism And The Contemporary Animal Protection Movement

The animal protection and anti-vivisection movements paved the way for today’s animal welfare and animal rights organizations. There are prominent differences between these two contemporary movements. Probably the largest and most notorious animal rights organization in the world today is PETA (People for Ethical Treatment of Animals), founded in 1980. This organization uses graphic emotional messages, in order to lobby against the use of animals for food (Meat is murder), clothing (I’d rather go naked than wear fur), research (Animal testing kills), entertainment (Wild animals belong in the wild, not in zoos), and other forms of animal use. Following the premises of deontological ethics, the abolitionist approach to animal protection works to eliminate virtually all forms of animal use, except maybe for companionship. In extreme circumstances, some animal rights organizations can resort to direct action, such as releasing animals from research laboratories.

In contrast, animal welfare organizations adhere mostly to a combination of utilitarian traditions, accepting the conditional use of animals, and relational-based ethics, by acknowledging the role of animals within society and the benefits of human-animal interactions. This reformist approach works to improve the lives of animals and include organizations such as the World Animal Protection (formerly WSPA), Compassion in World Farming, and the SPCAs across the world, such as ASPCA (US) and RSPCA (UK). These organizations, albeit zoocentric, tend to be pragmatic, generally accepting the use of animals for a societal good but placing an emphasis on supporting animal welfare. Thus, they work to reform human practices involving animals and to reinforce the human-animal bond.

Conclusion

Zoocentrism expands the circle of human moral consideration to include other, nonhuman, animals. It is a relatively recent concept, emerging from the anthropocentric social justice movement and evolving into the contemporary animal welfare and animal rights organizations. The key outcome of zoocentrism in Western societies has been the conferring and refinement of legal protection to a growing number of nonhuman animals, which constitutes unequivocal evidence of their rising moral standing.

Bibliography :

- Abbate, C. (2014). Virtues and animals: A minimally decent ethic for practical living in a non-ideal world. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 27(6):909–929.

- Arluke, A., & Sanders, C. R. (1996). Regarding animals. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Bentham, J. (1789). An introduction to the principles of morals and legislation. London.

- Cavalieri, P. (2001). The animal question – Why non-human animals deserve human rights. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Francione, G. (2000). Introduction to animal rights: Your child or the dog? Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Frey, R. G. (1979). What has sentiency to do with the possession of rights? In D. A. Paterson & R. D. Ryder (Eds.), Animals’ rights: A symposium (pp. 106–111). London: Centaur Press.

- Harrison, R. (1964). Animal machines: The new factory farming industry. London: Vincent Stuart [Reissued in 2013 by CABI Publishers].

- Hursthouse, R. (2006). Applying virtue ethics to our treatment of other animals. In J. Welchman (Ed.), The practice of virtue – Classic and contemporary readings in virtue ethics (pp. 136–155). Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company.

- Lund, V. (2006). Natural living – A precondition for animal welfare in organic farming. Livestock Science, 100, 71–83.

- Regan, T. (1983). The case for animal rights. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Regan, T. (2003). Animal rights, human wrongs – An introduction to moral philosophy. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Rodman, J. (1977). The liberation of nature? Inquiry, 20, 83–145.

- Rollin, B. E. (1992). Animal rights and human morality (Rev. ed.). Buffalo: Prometheus Books.

- Rollin, B. E. (2005). Reasonable partiality and animal ethics. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, 8, 105–121.

- Ryder, R. D. (2010). Speciesism again: The original leaflet. Critical Society, Issue 2, 1–2.

- Sandøe, P., Hocking, P. M., Förkman, B., Haldane, K., Kristensen, H. H., & Palmer, C. (2014). The blind hens’ challenge: Does it undermine the view that only welfare matters in our dealings with animals? Environmental Values, 23, doi:10.3197/096327114X13947900181950.

- Singer, P. (1975). Animal liberation. New York: New York Review of Books.

- DeMello, M. (2012). Animal and society: An introduction to human-animal studies. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Franklin, J. (2005). Animal rights and moral philosophy. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Haynes, R. P. (2008). Animal welfare – Competing conceptions and their ethical implications. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer.

- Sandøe, P., & Christiansen, S. B. (2008). Ethics of animal use. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.