This sample Pastoral And Spiritual Care Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality paper on argumentative research paper topics at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

This entry presents an overview of pastoral and spiritual care with regard to bioethical principles at the personal, communal, and international levels which, it can be argued, are progressively intersecting due to increasing globalization. The contribution of pastoral and spiritual care practitioners toward resolving bioethical dilemmas will be considered, as will the recognition and inclusion of religious, pastoral, and spiritual care, as an integral part of holistic person-centered care that not only benefits the individual, but also benefits communities both locally and globally.

Introduction

Depending on the context, pastoral and spiritual care can have a substantial and yet sometimes ambiguous prominence with regard to bioethical issues. This is due to the fact that pastoral and/or spiritual carers tend to be influential given their practical support to patients/clients rather than by asserting any formal authority. What is certain however is that all three domains (pastoral care, spiritual care, and bioethical issues) have interacted for centuries, either directly or indirectly. It is important to note at the outset, that while pastoral care and spiritual care have predominantly been grounded in religious traditions (of one kind or another), neither contemporary pastoral care nor present-day spiritual care accepts the traditional prism of viewing bioethical issues only in terms of defined religious or faith parameters but rather utilizes a holistic paradigm that emphasizes person-centered care as its core frame of reference.

The person-centered approach (also sometimes known as “client centered” or somewhat hierarchically as “patient centered”) was first coined by an eminent humanist psychologist Carl Rogers (1902–1987). Rogers was concerned with the power relationship within expert-client therapy and subsequently developed “nondirective therapy,” then “client-centered therapy,” and finally the “person-centered” approach. Essentially, Rogers shifted the focus of therapy away from professional expertise and advice, to focus upon facilitating the needs, desires, and goals of a person to achieve their own self-actualization.

It is important to note that a person-centered approach is not an ethical position per se but rather a process which ensures the focus is on the autonomous goals of the person and not purely based upon medical, religious, or other professional determinants. During the twentieth century, pastoral care, and subsequently spiritual care, largely adopted Roger’s humanistic person centered approach as a key methodology for pastoral care and counseling.

Unfortunately, understanding bioethics from a pastoral and spiritual care viewpoint has often been contrasted against “value-neutral” ethics – sometimes called secular or humanistic ethics. While some secular ethicists accept that moral judgments (secular or otherwise) can never simply be statements of fact, nevertheless, others subscribe to a perspective which assumes that in applying “scientific principles,” it is therefore possible to operate in a “value-neutral” environment.

Such a stance however ignores the reality that it is always humans who are applying ethical principles and they are never value neutral. Contemporary pastoral and spiritual care however, while recognizing the importance of religious and spiritual beliefs, argues for a broader and more inclusive approach to bioethical issues, not limited by any one specific dogma or philosophy – whether it be religious, secular humanist, or otherwise.

Contemporary pastoral and spiritual care is fundamentally multidisciplinary, with the primary aim of ensuring (through various pastoral and spiritual care practitioners) that religious, pastoral, and spiritual tenets are equally valued alongside other systems of belief. Pastoral and spiritual care strives to ensure that person-centered care is not just a perfunctory gesture of health-care policy but an effective and inclusive practice that should be assured, regardless of the type of bioethical issues – whether these are predominantly personal, communal, or global.

Hence one of the roles of pastoral/spiritual carers has been to provide support as facilitators during bioethical decisions to ensure that all issues/viewpoints are considered but most particularly that of the key person affected (Carey and Cohen 2008). Thus, it can be argued that while pastoral/spiritual carers strive to ensure that religious and spiritual care is an active ingredient of holistic person-centered care, they nevertheless have a meta-role, beyond the specifics of any bioethical issues, to ensure that bioethics itself, and bioethical decision making, is truly holistic and person centered in its application.

Conceptual Clarification

Within this entry, the term “pastoral care” and “pastoral carers” are recognized as long-established generic terms for religiously specialized work and the personnel designated to undertake that work – either as a result of being officially ordained and commissioned by a recognized religious organization (e.g., as priests, rabbis, ministers, monks, imams, chaplains, or other such bestowed clergy) or as a result of being approved as “volunteers” to assist in pastoral care work (e.g., as pastoral assistants, denominational assistants).

Most “chaplains” and some “chaplaincy assistants” not only have religious training and authorization to undertake religious and pastoral care duties but also are required to have additional specialist training beyond theological schooling so as to increase their professional utility (e.g., having secular tertiary qualifications, clinical pastoral education, and/or other specialist chaplaincy training relating to a specific context). Usuallychaplains also have professional association membership/accreditation and the endorsement of a secondary organization (e.g., hospitals/health department, military/department of defense, police/correctional services, universities/schools).

While it can be argued that the term “spiritual” also has a long-established history, nevertheless, the terms “spiritual care” and “spiritual carer” are more recent terms that have predominantly arisen as a result of the shift from the “biopsychosocial” model (which has been largely antireligious) toward a broader and more inclusive “biopsychosocial-spiritual” model (Sulmasy 2012). Given that the definition of spiritual means relating to or affecting the human spirit or soul, as opposed to material or physical things, both pastoral care and spiritual care have a great deal in common, except that pastoral care is more religiously grounded and focused, whereas “spiritual care” is much broader (as will be defined later) recognizing both traditional religious beliefs and more contemporary spiritual practices. Nevertheless, for the purposes of this entry regarding bioethics, both the terms “pastoral” and “spiritual” are virtually inseparable and will be equated together as “pastoral/spiritual” and “pastoral/spiritual carer.”

This entry will provide an overview of pastoral care, spirituality, and the bioethical principles, particularly as these relate to the role and contribution of pastoral/spiritual carers. Consideration will then be given to the different bioethical dimensions in which pastoral/spiritual carers pragmatically engage in bioethical issues – namely, at the personal, communal, and global levels. Finally, the recognition and inclusion of religious, pastoral, and spiritual care will be noted that ensures a truly holistic approach to person-centered care.

Historical Development

Pastoral Care

The word “pastoral” derives from the Latin word for “shepherd” or “shepherding” – meaning protecting, caring for, or curing something (or someone) in need – hence the extension “pastoral care.” The act of “shepherding” is strongly emphasized within both Judaism and Christianity, as recorded in historic biblical passages such as Psalm 23 (“The Lord is my shepherd”) or within New Testament texts such as the Gospel of John (Chapter 10: “I am the good shepherd”). However, given that sheep farming and the practical caring for sheep have been universal in many cultures across the world, the concept of shepherding and “being a good shepherd” was also utilized or adopted by many faiths such as Islam, Buddhism, and Hinduism.

For centuries, the traditional approach to pastoral care, which involved religious and spiritual leaders caring for their flock of constituents (using their particular established theological dictates), was fundamentally altered post WWII. Within the Western world, from the 1950s, “pastoral care,” based on the progressive work of Richard Carbot (1868–1939), Anton Boisen (1876–1965), and Howard Clinebell (1922–2005), broadened from a purely religious/theological concept to incorporate psychological theories, including the development of pastoral counseling as a specialist discipline within pastoral care. Subsequently, pastoral care, rather than being religiously mission orientated, became more person centered, irrespective of a person’s/client’s religious or nonreligious preference.

By the latter half of the twentieth century, pastoral care, both in definition and practice, extended to become internationally defined as any “.. .helping acts directed towards the healing, sustaining, guiding and reconciling of troubled persons whose troubles arise in the context of ultimate meanings and concerns” (Clebsch and Jaekle 1967, p. 4). This was an important development with respect to bioethical issues, for while religious dictates may or may not have condoned particular bioethical decisions (e.g., abortion, euthanasia), nevertheless the focus of modern post-WWII pastoral care was not to judge or condemn individuals but to provide support to assist with healing, sustaining, reconciling, and, hopefully, guiding individuals toward better health and well-being decisions.

Paterson (2015) noted that such early definitions of pastoral care tended to blame troubled individuals for their own condition, whereas, given the increasing recognition of social determinants that effected the health and well-being of people, pastoral care from the late 1980s started to shift purely from a clinical perspective to reiterate the importance of contextual and communal influences. Subsequently, by the commencement of the twenty-first century, pastoral care had already further extended to consider social and cultural determinants plus the nurturing of ecologically holistic communities within an international/global context.

A review by Hart (2002) indicated that the progression of pastoral care as a discipline, and the practical contribution of pastoral/spiritual carers to bioethics and bioethical issues, has been considerable over the years – particularly within the health-care context. Hart was perhaps the first to identify the correlation between bioethical principles and pastoral/spiritual care noting numerous ways by which pastoral care, through its appointed practitioners, had contributed to modern-day bioethics and the resolving of bioethical issues at both personal and communal levels. He noted eight key contributions of pastoral/spiritual care practitioners to bioethical issues:

- Developing rapport with patients and staff so as to assist with reaching into the “patient’s world” and assessing potential sources of anxiety regarding bioethical decisions and treatment.

- Establishing a common ground among competing interests (e.g., patients, family, community, professional staff, hospital administration) in order to facilitate mediation and resolve bioethical questions and conflicts.

- Ensuring “ultimate concern” for patients in a health-care setting that should not revolve around organizational interests and employee satisfaction, regulatory services, and budgetary restructuring but primarily focuses upon human care of the sick according to highest clinical practice standards and grounded in science and research (ultimate concern is a concept originally developed by Paul Tillich (1886–1965)).

- Assisting health-care organizations with ethical reflection with respect to balancing competing goods and interests and distinguishing means and ends plus a capacity to separate expediency and deliberate or semi-deliberate rhetorical obfuscation from the overall mission of the health-care institution or organization.

- Presenting/speaking to religious and community groups (e.g., congregations, schools, universities, community meetings) about pastoral and spiritual care applicable to health-care and bioethical issues.

- Writing articles for publication (e.g., newsletters, journals) regarding bioethical issues and advocating on behalf of patients/families the bioethical principles of autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, justice, and supplementary issues of privacy and confidentiality.

- Serving on commissions, panels, and committees (e.g., institutional ethics committees, human research ethics committees, hospital boards) making certain that the concerns of patients, particularly related to faith and the inner life, become integral to the decision-making process and organizational policy.

- Utilizing tacit knowledge/expertise/research to present at educational seminars (e.g., medical conferences, continuing education seminars) to benefit health-care staff and the wider community about pastoral, spiritual care, and bioethical issues.

A unique twenty-first century contribution to pastoral/spiritual care has been the development of the World Health Organization “Pastoral Intervention Codings” (colloquially known as the “WHO-PICs”), which recognized and designated pastoral interventions within WHO’s International Classification of Diseases and Health Related Problems coding system (ICD-10). Some health/welfare organizations and national health services around the world have sought to develop their own idiosyncratic pastoral/spiritual care coding system; nevertheless, a review of the WHO-PICs indicated that the major WHO-PIC coding intervention categories were found to be specific enough to identify the core pastoral/spiritual care intervention yet flexible enough to incorporate a range of sub-elements relevant to varying contexts/situations within both health (e.g., acute, mental, aged care) and welfare settings (e.g., prisons, military) (Carey and Cohen 2014).

While it has been proposed that the WHO-PICs should be revised to be more inclusive and titled the “Religious, Pastoral and Spiritual Intervention Codings” (WHO-REPSICs), nevertheless, irrespective of such possible amendments, the codings have already proven invaluable for recording the involvement of pastoral/spiritual carers in bioethical issues when undertaking (i) assessments, (ii) support, (iii) counseling, and (iv) education plus (v) ritual and worship activities plus related (vi) religious, pastoral, and spiritual administration in response to patient/client, family, and other personnel needs (Carey and Cohen 2014).

Spiritual Care

Over centuries the concept of spirituality has changed considerably – particularly within the Western world. Muldoon and King (1995) summarized the progression of spirituality, noting that one of the earliest and most detailed notations regarding “things of the spirit” since the commencement of the Common Era was that of Saint Paul’s work distinguishing the “spiritual person” from that of the “natural” or “carnal” human (1 Corinthians 2: 15) – suggesting that an individual’s perspective and behavior (and thus ethical decisions) were affected by their spiritual status.

By the Middle Ages, however, spirituality tended to emphasize a distinction between those who wrongly put their trust in materiality and those whose persuasion was primarily religious with ultimate concerns. The thirteenth to sixteenth centuries saw this distinction furthered given the progressive separation of religion and state power, whereby religious philosophy, property, and power were distinguished from secular authority and ownership – and thus spirituality primarily became the administrative concern of specialists such as clergy.

From the seventeenth century, however, and one could argue to the present day, there has been a reclaiming of “spirituality” with respect to its personal significance and merit. Muldoon and King (1995, p. 331) noted that while “spirituality” could be used pejoratively to indicate questionable religious enthusiasm or unorthodox forms of religious practice (or even, one could add, the personal criticism of “being too heavenly minded and subsequently of no earthly use”), nevertheless, spirituality predominantly became a term referring to one’s interior quality and one’s devotion to an affective relationship with a divine being.

By the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, this led to a distinction between those having a “common life of faith” and those striving for perfection through mentorship, spiritual exercises, and the practice of virtues beyond what was ordinarily expected. Subsequently, over the years, given the changing emphasis of “spirituality,” there has been considerable deliberation concerning the meaning of spirituality and spiritual care. Fundamentally, the pondering has been due to the term “spirituality” being difficult to define given a multiplicity of confounding descriptions that have ultimately hindered holistic practice, patient-centered care, and appropriate spiritual care interventions.

The first “consensus” definition of spirituality to emerge, which has gained increasing acceptance and largely resolved the debate (at least among some conciliatory academics and pastoral/spiritual care practitioners), predominantly arose out of the palliative care context, defining spirituality as:

…the aspect of humanity that refers to the way individuals seek and express meaning and purpose and the way they experience their connectedness to the moment, to self, to others, to nature, and to the significant or sacred. (Puchalski et al. 2009)

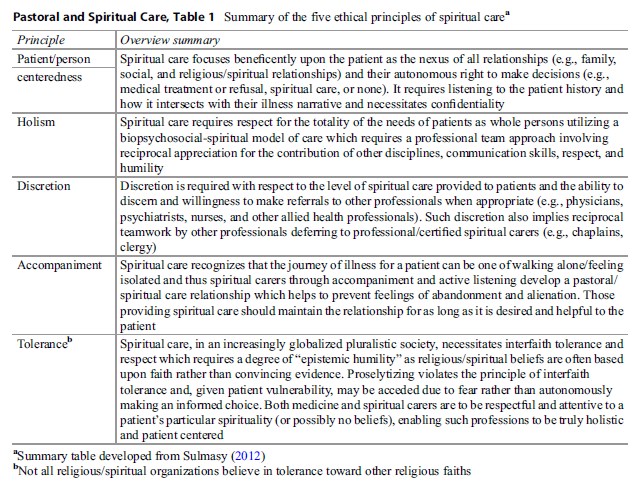

This definition of spirituality automatically advocates for a person-centered care approach and, if accepted, necessitates certain ethical principles to ensure that person-centered care is respected as a legitimate part of a spiritual care approach. Sulmasy’s (2012) work is helpful in this respect, noting that there are a number of ethical principles of spiritual care that need to be maintained in order to ensure that pastoral/spiritual care is patient centered – namely, holism, discretion (referral), accompaniment, and tolerance toward those of a different faith belief compared to one’s self (see Table 1).

Bioethics

The term “bioethics,” from Greek words “bios,” meaning “life,” and “ethikos,” meaning “habit” or “custom,” can technically and rather simply be interpreted to mean the application of habits or past customs upon the whole of life. Such a definition however is too broad as it could include almost anything in terms of ethics (e.g., business ethics, political ethics). More current with today’s usage, bioethics is generally taken to refer to the “.. .application of ethics to the biological sciences, medicine, health care and related areas as well as the public policies directed towards these” (Childress 1986).

Table 1. Summary of the five ethical principles of spiritual carea

Table 1. Summary of the five ethical principles of spiritual carea

While there has been some debate about the cogency and latitude of Beauchamp and Childress’s (2013) four Principles of Biomedical Ethics ( fp 1977), nevertheless, these have become foundational and warrant discussion with regard to pastoral/spiritual care:

- Autonomy – The principle of respecting an individual deciding his or her own choice

- Beneficence – The principle of acting with the best interest of the other in mind

- Non-maleficence – The principle that “above all, do no harm”

- Justice –The principle of fairness and equality among individuals

The Principle Of Autonomy

Autonomy, etymologically, is a compound of the Greek words “autos” (self) and “nomos” (law or rule). In simple definition terms, it means “self-rule” or “self-government.” At a macro level, “autonomy” was originally used to refer to the independence of city-states from outside control. At a micro level, it generally refers to a person’s ability to make or to exercise a self-determining choice, literally to be self-governing.

It is not possible to discuss all the issues relating to autonomy within this entry. Wheeler (1996, p. 40) however summarized a pastoral care cautionary for all pastoral/spiritual care practitioners with respect to autonomy. In order for autonomous decisions to be properly appropriated, particularly with regard to bioethical decisions, pastoral/spiritual carers can help to ensure that four distinct requirements are assured, namely, (i) full disclosure to patients, (ii) comprehension by patients, (iii) voluntaryism involving no coercion or cajoling, and (iv) patients being properly assessed as mentally competent and emotionally stable.

Although ensuring a person’s autonomy may seem quite straightforward, in actual fact it is not. Religious ethics sometimes mandates a form of constraint with regard to autonomous decision making that can challenge personal morality or acceptable communal consent. For example, within Islam, one’s autonomy can be limited or constrained because Muslims are mandated to “submit” to certain “prohibitions” that may severely limit their autonomous options, and their failure to comply may result in some form of familial or social reprimand, possibly with legal or life-threatening consequences depending upon the cultural milieu. Though not quite as arduous, other religions (e.g., Judaism, Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism) support in one way or another that the concept of autonomy could be a “sinful” assertion if one fails to acknowledge one’s dependence upon a divine/superior authority or ultimate life source. Thus the struggle for people between making autonomous decisions and the constraints of their religious belief can amount to interpersonal and intrapersonal conflicts that can form a regular part of a pastoral/spiritual carer’s counseling role given bioethical dilemmas.

Non-maleficence

Maleficent means to be “hurtful” toward others, even “criminal” or with intent to be “evil” in the treatment of others. The opposite is non-maleficence. Childress argued that the principle of non-maleficence “establishes the duty not to harm others or injure others or impose the risks of harm on them, at least without compelling justifications for doing so” (Childress 1986, p. 425).

The principle of non-maleficence is based upon the maximum or oath purportedly written by Hippocrates of Kos (460–377 BC), primum non nocere, that is, “first, do no harm.” The Hippocratic Oath became a “professional ethic”, specifically developed to distinguish trained physicians apart from other self-proclaimed practitioners who, due to a lack of training or for political or financial gain, acted immorally by causing harm and injustice to their patients (Fletcher 1986, p. 269). During the twentieth century, some ethicists believed that the principle (in its original form) to be “so general that it is useless” on the grounds that it is impossible to avoid all harm or “evil.” Indeed if all harm or the possibility of harm was avoided, no health risks for improvement would ever be undertaken and therefore a greater harm may result – namely, death. Hence the argument that the principle of non-maleficence is only appropriate as a professional ethic when there is no compelling reason to ignore it.

However, the fundamental principle and first loyalty noted in the Hippocratic Oath was not, in the first instance, about professional integrity per se but the importance of patient-centered care. To state it simply, the Hippocratic Oath was primarily about patient well-being and “patient protection” which was not to be risked by the political and financial agendas of others. While there are obvious limitations in continuing to use the Hippocratic Oath given modern medicine, there is nevertheless continued merit in the oath, not just because it still has relevance for bioethical issues that are still currently debated (e.g., abortion, euthanasia) but because of its essential emphasis upon patient centeredness – that is to say, it is not the words as such but the values implied in the oath that are important.

Indeed over time, priority in favor of the patient has been reechoed in other medical codes such as the “Geneva Convention Code of Medical Ethics (1949)” stating, “The health of my patient will be my first consideration,” and the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki (Finland 1964) and amendments (Japan 1975; Venice 1983; Hong Kong 1989) stating, “It is the mission of the physician to safeguard the health of the people. His or her knowledge and conscience are dedicated to the fulfillment of this mission.” Indeed numerous codes such as the Nuremburg Code (1947), the Nightingale Pledge (1947), the Declaration of Sydney (1968), the Declaration of Tokyo (1975), and the Declaration of Hawaii (1977) are indicative that non-maleficence and principles related closely to it (e.g., beneficence) have been regular and recurrent concerns among both health professions and the wider community. The focus of pastoral/spiritual carers is to likewise support the principle of non-maleficence by ensuring patient-centered care through the provision of religious, pastoral, and spiritual support and if necessary advocacy, particularly for those vulnerable patients unable to defend for themselves.

Beneficence

Beneficence means “active well doing” or “doing good so that another is able to experience greater good or happiness”. More specifically, with regard to bioethics, beneficence can mean simply the “duty to care” or “the duty to do the best for an individual patient.” While the principle of non-maleficence (mentioned earlier) can be seen to be relatively passive in its aim, requiring “a person to do no harm to another,” beneficence demands the intentional and direct application of care for the advancement of someone’s health and well-being.

Some argue however that “beneficence,” as a result of medical dominance, has become an excuse for “paternalism,” “infantilizing,” or “creating dependency” of patients upon medical physicians due to their overriding of a patient’s autonomy, either by deception or by coercion (supposedly) for the sake of “benefiting” the patient. Examples of this may include failing to obtain the informed consent from a patient, misleading a patient about the risks of surgery, exercising undue influence over the patient’s decision, failing to inform or withholding information, lying to a patient about their condition, failing to include the patients (and their families) in decisions about treatment, or altering a patient’s treatment decisions without consent (Wheeler 1996).

The corruption of “beneficence” by some unscrupulous medical practitioners has led to the principle of “beneficence” sometimes receiving a degree of “bad press.” Thompson et al. argued however that beneficence involves important aspects such as “patient advocacy and defending the rights of vulnerable patients” – aspects which should not be left amiss:

Beneficence is indispensable wherever there are dependent or helpless people in need of support or urgent care and attention. The reciprocity in our duty to care of one another should make us realize that we all need others to speak for us, to do things for us, or to defend our rights when we are too weak to do so for ourselves. (Thompson, et al. 1994, p. 61)

An important aspect with regard to the beneficent role of pastoral/spiritual carers can be understood with regard to knowledge. Thompson et al. (1994, p. 61) noted that “knowledge is power” and that the power of the true carer is aimed at “sharing knowledge and skills with the vulnerable individual so as to empower that person to reassert control over his/her life.. ..” Similar to the role of clinical ethicists and religious representatives on institutional/research ethics committees, pastoral/spiritual carers can have an important nonclinical independent role in helping to ensure that patients and clinicians are reminded of patients’ autonomous rights and that patients (and their families) have the opportunity to be fully informed about their options regarding treatment and the minimum requirements for autonomous decisions (as noted earlier, refer to Autonomy).

The Principle Of Justice

While there is some debate regarding the principle of justice, generally, most bioethicists would support the definition that the “principle of justice” (or as it is sometimes referred to the “demand for universal fairness”) means “the fair sharing” or “fair distribution” of a society’s benefits and burdens and of rewards and punitive controls among its members. With respect to pastoral and spiritual care, justice can be divided into three levels of allocation and subsequent action: “micro,” “meso,” and “macro” justice. Each can be an important area of involvement for pastoral and spiritual care practitioners as each correlates with personal, communal, and global bioethics (noted later).

Micro-allocation concerns the local issue of who should receive scarce resources such as kidney organs or supplies of a rare blood type or which individual will be given a bed in the intensive care unit, particularly given the limited availability and increased demand. This level also includes decisions concerning the allocation of time via the use of appointments, waiting lists, triage diagnostic, and treatment decisions. It is also an area involving “procedural justice” that considers “how we decide who receives care, how long they must wait for it, and what quality of care they have access to.” The local hospital, for example, may have ample resources and staffing to administer lifesaving procedures, but prescribed hospital procedures, hospital decision makers, or even government policy may deny access to some patients (Wheeler 1996, p. 60).

Whether the denial is due to discrimination on the basis of sex, race, religion, age, disease, mental illness, wealth, or the level of health insurance, the consequences of discriminate justice can have disastrous effects for those prejudiced against. It is arguable that pastoral/spiritual carers within health-care institutions have some responsibility in this arena, given their professional mandate to care for all – irrespective of race, creed, or status – and to encourage a more just and hospitable environment, particularly through providing support and advocacy for patients.

Meso-allocation is the allocation of medical resources at a regional level including decision makers such as administrators, hospital managers, and institutional committees, who are responsible for allocating resources to various hospital departments (including pastoral/spiritual care departments), regional competing services, health-care specialists, and allied health services and programs. At this level, pastoral and spiritual carers compete with other departments and programs for funding. Mostly pastoral and spiritual carers have relied on the “goodwill” of health-care administrators for funding. More recently, however, economic rationalism within health-care contexts has meant that pastoral/spiritual carers have had to provide more empirical evidence/ research utilizing religious, pastoral, and spiritual care codings to record their services undertaken with patients, their family, and staff (Carey and Cohen 2014).

Macro-allocation primarily occurs at the government level with regard to the proportion of national and state income which will or will not be spent, for example, on health, education, welfare, transport, and defense. Macro-allocation, for example, involves concerns about whether increased allocation of resources should be shifted from more privileged sectors to deprived areas so as to bring greater equality within society and/or whether tax dollars should be restricted with respect to the aged and instead allocated directly to organ transplantation or to clinical research.

As will be noted later, macro-allocation also affects the distribution of resources at a global level that might assist poorer nations struggling with disease. Due to limited resources, any macro decisions subsequently affect meso and micro allocations, particularly in terms of the availability and accessibility of resources within local communities.

Given their training in health care, all health professionals (including pastoral/spiritual carers) concerned for the principles of justice should “campaign for resources” or “defend standards of care” so as to improve services within a nation, state, or community, particularly for those people underprivileged, aged, or disabled. Yet while such issues of justice are of social and pastoral concern to many, particularly to health-care pastoral/spiritual carers, “macro-”decisions seldom, if ever, involve the participation of pastoral/spiritual carers who are often excluded in such policy decisions.

Of course macro-allocation will substantially affect micro and meso-allocations and thus the availability of pastoral/spiritual care staffing and local resources. This in turn will significantly affect and challenge their role in terms of the level of pastoral/spiritual care they are able to provide and fundamentally can undermine patient-centered care. Thus while the predominant participation of pastoral/spiritual care currently occurs at the micro level of decision making, nevertheless, meso and macro distributive justice can and will increasingly be as important – particularly given the growing recognition of faith-based organizations/communities in providing care within regions having limited resources and/or are poverty stricken.

Bioethical Dimension

It is important to note that most of the literature and research relating to pastoral and spiritual care with regard to bioethical issues has been within the health-care context and largely driven by the demands of health care chaplains working within acute care, mental health care, and aged and palliative care services. There is also however literature noting religious pastoral/spiritual carers dealing with bioethical issues that have had, or currently have, global significance (e.g., HIV/AIDS).

From a pastoral/spiritual perspective, all bioethical issues are globally interconnected, in one way or another – whether this be due to social, legal, political, religious, economic, or (more than likely) a permutation of many dynamics. Traditionally, however, and irrespective of numerous influences, it is possible to generalize that the application of pastoral/spiritual care with respect to bioethical issues has tended, for pragmatic reasons, to be interventions at either (a) personal, (b) communal, or (c) international levels – but many of which are increasingly interconnected due to developing globalization.

Personal

A number of bioethical issues and related decisions, while frequently occurring around the globe, nevertheless reflect a personal or familial situation. Thus far the only quantitative and qualitative international studies exploring the role of pastoral/spiritual carers involved in patient bioethical decisions involved Australian (AU n = 324) and New Zealand health-care chaplaincy personnel (NZ n = 100). The results indicated that, irrespective of the population, of all the bioethical issues encountered by pastoral/spiritual care personnel, it was the personal end-of life decisions such as pain control, withdrawal of life support, and organ donation in which the majority assisted (Carey 2012a; Carey and Cohen 2008).

The qualitative results gathered in the same studies indicated that while a minority of chaplains preferred not to engage in bioethical decisions at all, nevertheless, the majority of chaplains believed that it was part of their role to help patients and their families make health care treatment decisions and that such involvement typically occurred through various pastoral interventions, namely, pastoral/spiritual assessments, ministry/support, counseling, education, and/or pastoral ritual and worship activities, that aided patients, their families, and sometimes staff.

Communal

There are a number of bioethical issues also encountered by pastoral/spiritual carers that could likewise be considered personal yet tend to have more communal impact and involvement. Perhaps the most common bioethical issues that can involve pastoral/spiritual carers at the communal level are matters such as abortion, organ transplantation, palliative care and in-vitro fertilization (IVF).

Abortion, while argued to be a complex issue on a personal level and thus argued by pro-abortionists to be a matter of autonomous right and personal decision, nevertheless, abortion remains a socially controversial issue within some religious and nonreligious communities alike, who predominantly argue that abortion is a maleficent act, demanding “justice” and the “right to life” for unborn infants and emphasizing the sanctity of life with adoption as a preferred resolution, if necessary, for the benefit of the child, those who are unable to have children, and, eventually, the community. Pastoral/spiritual carers, while perhaps embracing strongly held religious and personal views about abortion, nevertheless, in their professional capacity, are required to practice person centeredness and accompaniment (Table 1) by providing a range of religious, pastoral, and spiritual interventions (i.e., assessment, support, counseling, education, ritual, and worship) as required to assist the patient/client irrespective of their or the patient’s/client’s views and decision.

Likewise IVF is also argued by some to be an autonomous right and personal lifestyle choice that can benefit heterosexual, homosexual, and transgender couples unable to have their own children through their own natural procreation. However, it has also been a socially controversial bioethical issue given the artificial-technological process involved plus the substantial and repetitive costs that are often subsidized by the community and/or governments in one way or another, causing additional strain upon finite resources and technology that could otherwise have been directed to lifesaving infrastructure (e.g., kidney dialysis, cancer treatment).

The fundamental point to note however, with respect to personal bioethical issues, is that no matter where one stands on the spectrum concerning bioethical issues, such as IVF or abortion, and recognizing that people (including pastoral/spiritual carers) are never “value neutral,” nevertheless, ethically and professionally, the pastoral/spiritual carer’s role is to be “person centered.” This requires a holistic approach to be discrete, provide accompaniment, and advocate for acceptance and tolerance of other’s beliefs rather than the forceful imposition of beliefs and values on either the patient/client or family.

Of all the communal bioethical issues, organ transplantation (OTP) is perhaps one of the most demanding for pastoral/spiritual carers. While communal bioethical issues such as abortion and IVF may be socially debatable and controversial, there is general communal agreement in most countries regarding the beneficence of OTP – irrespective of community cost. The social challenge and controversy however has essentially been due to the high demand yet limited supply of organs – a phenomenon that is common worldwide and increasingly shifting from a communal issue to a global issue given the emergence of medical tourism in general and the development of organ tourism particularly in terms of further exploitation of poorer countries.

While research indicates that organ transplantation is not the most frequently encountered bioethical issue for pastoral/spiritual carers, nevertheless, it involves and requires the most comprehensive forms of pastoral/spiritual care, sometimes demanding preoperational assessment, support, counseling, and education, as well as during surgery (for family and staff) and postoperative support (for patients, family and staff). One unique and identified role of chaplains as part of their assessment, for example, has been to discuss with patients/families about the possibility of potential organ donation given the likelihood/inevitability of a patient’s death. The pastoral/spiritual carers’ independent nonmedical perspective and the communal/global shortage of organs mean that their role can be sensitively influential in assisting timely patient/family decision making. Given the emotional tenderness of patients and/or families near or at a time of death, this is an awkward task that despite the most diplomatic protocols is sometimes reciprocated with aggressive negativity. Nevertheless, pastoral/spiritual carers are also aware that patients/ families can feel quite disappointed if the opportunity of making a lifesaving donation was not sufficiently forthcoming as a possible option.

International

Internationally, there are a number of ongoing bioethical issues that have sorely affected entire nations (e.g., as a result of cancer, SARS, and more recently the Ebola virus) which have necessitated the involvement of pastoral/spiritual carers in one way or another. In particular, the last quarter of the twentieth century witnessed the outbreak and rapid rise of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), causing substantial morbidity and the death of thousands of people around the globe. The twenty-first century also continues to experience wars and social upheaval, particularly within regions dominated by Islamic theocracy and extremism, resulting in acts of genocide, homelessness, disability, poverty, starvation and consequently generations that will suffer mental and moral injury.

The work of Miller and Rubin (2011) highlighted the important health communication role that local faith-based-communities (FBCs) and faith-based organizations (FBOs) can have in their respective regions when struggling with substantial health and bioethical issues. These nongovernmental organizations have also been noted to provide a variety of basic needs and services that have assisted communities in their struggle to survive – needs such as food and water to the more advanced services such as health-care facilities. In summary, Miller and Rubin’s work identified seven areas that faith based organizations/faith-based communities addressed global community bioethical issues:

- Provide and assist with physiological needs (e.g., food, water, shelter, clothing).

- Provide and assist with security and safety needs (e.g., personal, financial, health services).

- Encourage/ensure a sense of belonging (e.g., friendship, family, community).

- Encourage and assist individual and community esteem (e.g., self-respect, acceptance, and consideration for others).

- Encourage and assist with individual and community development (e.g., helping people/ communities actualize desired goals such as education, schools, housing, hospitals, and community utilities).

- Provide individual and community health promotion/communication of information suitable to cultural context and religious/community activities (e.g., religious ceremonies/community celebrations) utilizing appropriate language/dialect.

- Provide clinical and supportive personnel/ expertise to administer medical and allied health services plus advise, counsel, and guide individuals and communities to negotiate and solve bioethical issues and problems.

The key resolution for international organizations such as WHO (World Health Organization), UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization), and the WCC (World Council of Churches), when attempting to deal with global bioethical issues, is to utilize and maximize the potential public health communication role and support of existing local FBOs/FBCs and their respected pastoral/spiritual leaders and/or chaplains. Such an alliance can help to provide accurate information and support to affected communities that, in turn, will help to lessen both ascribed and achieved stigmatization of those affected and ensure justice at all levels (personal, communal, and global) concerning the equitable distribution of resources so as to improve the health and well-being of communities around the world.

Conclusion

Contemporary pastoral and spiritual care has progressively developed since the mid-twentieth century concurrent with the progression of bioethics. Pastoral/spiritual carers, as part of their everyday role, are compelled to take into consideration the key principles of bioethics (i.e., autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, justice) plus the ethical principles of spiritual care, a combination of which makes a very robust framework for all pastoral/spiritual carers to ensure person-centered and holistic care at multiple levels (e.g., personal, communal, and global). Given their past and current degree of involvement in bioethical issues, plus their training and local tacit knowledge, pastoral/ spiritual carers should continue to be fully encouraged and endorsed to provide religious, pastoral, and spiritual care interventions with respect to bioethical issues and decisions, so as to ensure ongoing and proper holistic person-centered care.

Bibliography :

- Beauchamp, T. L., & Childress, J. F. (2013). Principles of biomedical ethics (7th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Carey, L. B. (2012a). Bioethical issues and health care chaplaincy in Aotearoa New Zealand. Journal of Religion and Health, 51(2), 323–335.

- Carey, L. B., & Cohen, J. (2008). Religion, spirituality and health care treatment decisions: The role of Chaplains. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy (US), 15(1), 25–39.

- Carey, L. B., & Cohen, J. (2014). The utility of the WHO ICD-10-AM pastoral intervention codings within religious, pastoral and spiritual care research. Journal of Religion and Health. New York: Springer Online First, September. doi:10.1007/s10943-014-9938-8.

- Childress, J. F. (1986). Medical ethics. In J. F. Childress & J. Macquarrie (Eds.), A new dictionary of Christian ethics (pp. 374–375). London: SCM Press.

- Clebsch, W. A., & Jaekle, C. R. (1967). Pastoral care in historical perspective. New York: Harper & Row.

- Fletcher, J. C. (1986). Hippocratic Oath. In J. F. Childress & J. Macquarrie (Eds.), A new dictionary of Christian ethics (pp. 268–269). London: SCM Press.

- Hart, C. W. (2002). The contribution of pastoral care to bioethics: Applying theology in a healthcare setting. Second Opinion, Jan(9), 4–14.

- Miller, A. N., & Rubin, D. L. (Eds.). (2011). Health communication and faith communities. New York: Hampton Press.

- Muldoon, M., & King, N. (1995). Spirituality, health care and bioethics. Journal of Religion and Health, 34(4), 329–348.

- Paterson, M. (2015). New Wine? New Wineskins? Values-based reflections on the changing face of healthcare chaplaincy. Health and Social Care Chaplaincy 2(2), 255–266.

- Puchalski, C., Ferrell, B., Virani, R., Otis-Green, S., Baird, P., Bull, J., Chochinov, H., Handzo, G., Nelson-Becker, H., Prince-Paul, M., Pugliese, K., & Sulmasy, D. (2009). Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: The report of the consensus conference. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 12(10), 885–904.

- Sulmasy, D. P. (2012). Ethical principles for spiritual care. In M. Cobb, C. Puchalski, & B. Rumbold (Eds.), The Oxford textbook of spirituality in healthcare (pp. 465–470). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Thompson, I. E., Melia, K. M., & Boyd, K. M. (1994). Nursing ethics (3rd ed.). London: Churchill Livingston.

- Wheeler, S. E. (1996). Stewards of life: Bioethics and pastoral care. London: Abingdon.

- Carey, L. B. (2012b). The utility and commissioning of spiritual carers. In M. Cobb, C. Puchalski, & B. Rumbold (Eds.), The Oxford textbook of spirituality in healthcare (pp. 397–407). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Koenig, H., King, D. E., & Carson, V. B. (2012). Handbook of religion and health. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Swift, J., Handzo, G., & Cohen, J. (2012). Healthcare chaplaincy. In M. Cobb, C. Puchalski, & B. Rumbold (Eds.), The Oxford textbook of spirituality in healthcare (pp. 185–190). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.