This sample Patient Rights Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality paper on argumentative research paper topics at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

The right to health and well-being is a fundamental right that influences all aspects of life. The most effective way for health care professionals to fulfill their obligations under the “right to health” approach is to ensure that they provide the highest possible standard of care while respecting the fundamental dignity of each patient. This entry is designed to give the reader a basic introduction to patient rights. It will focus on the doctor–patient relationship and present areas of greatest concerns. Patient rights are those basic rules of conduct between patients and medical caregivers, covering such matters as access to care, respect, communication, patient dignity, confidentiality, and consent to treatment. Patients have the right to be treated and dealt with in a humane and respectful manner. Health care providers are urged to pay careful attention to this vital aspect of clinical management; they must keep the welfare and the rights of the patient above any other consideration. Most countries outline fundamental elements of the doctor–patient relationship in their Code of Medical Ethics.

Introduction

Human rights are universal and indivisible rights, possessed by all people, by virtue of their common humanity. The right to health and well-being is a fundamental right that influences all aspects of life. The most effective way for health care professionals to fulfill their obligations under the “right to health” approach is to ensure that they provide the highest possible standard of care while respecting the fundamental dignity of each patient. Governing bodies should respect, protect, account, and fulfill patients’ rights. Nevertheless, these rights need further refinement from professional health care providers, patients’ relatives and friends, and the patients themselves toward their own bodies.

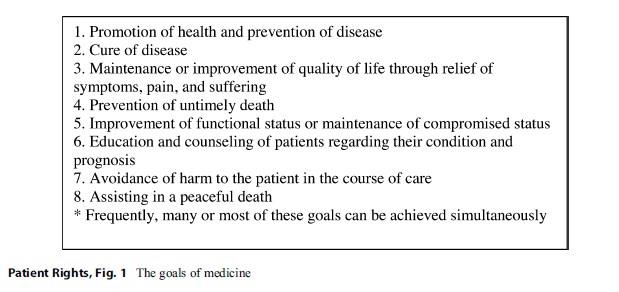

Figure 1. The goals of medicine

Figure 1. The goals of medicine

Figure 2. Remodeling of the physician–patient relationship

Figure 2. Remodeling of the physician–patient relationship

The goals of medical intervention in front of a patient will differ depending on the clinical facts of a case. Medical goals in a particular case may include one or several of the following: promotion of health and prevention of the disease, maintenance or improvement of the quality of life, cure of the disease, improvement of functional status, avoidance of harm, and assisting in a peaceful death (Fig. 1).

Frequently, many or most of these goals can be achieved simultaneously. In all cases, patients and physicians should clarify the goals of intervention when deciding on a course of treatment and should always take account of the patient’s own goals. This is what we call the remodeling of the patient–physician relationship with a gradual shift from traditional paternalism to a patient-centered model (Fig. 2).

History And Development

Historically, transition from paternalism to autonomy started in 1914, with a decision issued by the New York Court of Appeals in 1914 following the Schloendorff v. Society of New York Hospital, which stated that “Every human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what shall be done with his own body” (Schloendorff 1914). Another reported event happened in 1976, with Karen Ann Quinlan – persistent vegetative state on a ventilator; the New Jersey Supreme Court recognized the principle of a surrogate decision maker speaking for an incompetent patient (Fine 2005).

More recently, the health and human rights movement has grown with the expansion of the human immunodeficiency virus/acquired

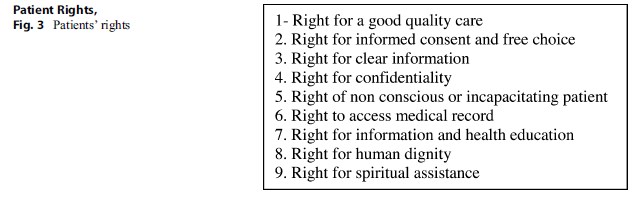

Figure 3. Patients’ rights

Figure 3. Patients’ rights

immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) pandemic. Then appeared developments in the academic field with the growth of health and human rights training programs, especially in medical and public health schools; the creation of specific professorships at universities; the addition of scientific journals focusing on health and human rights; and international conferences (Mpinga et al. 2011).

There are many challenges in different countries in the world concerning patients’ rights, among which are the economy, health systems, and inappropriate vision and/or analysis. It is well known that it will not be possible to provide all forms of health care in every country, as they are different in many respects. Even if it is not affordable at present, a future plan is necessary. In this regard, Mary Robinson from the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) stated that the right to health does not mean the right to be healthy nor does it mean that poor governments must put in place expensive health services for which they have no resources, but it does require governments and public health authorities to put in place policies and action plans which will lead to available and accessible health care for all, in the shortest possible time (Asher et al. 2007; Gruskin 2006).

The Patients’ Rights

The oldest (more than 2,500 years old) medical code is in The Hippocratic Corpus, otherwise known as the Hippocratic Oath, which contains several elements, emphasizing the commitment to the well-being of patients (Veatch 1997).

The medical ethics that has developed over the centuries has been altered by religion, social change, and behavior of physicians and patients. An additional and newer influence on medical ethics is the human rights movement. A fundamental concept of the human rights movement is that the decisions are made autonomously by informed patients. Human rights are a dominant force in the society and have substantial, positive implications for health care and medical ethics (Sheldon 1998).

They had certainly a positive impact on the development of patients’ rights. These rights are summarized in Fig. 3 and are related to the modern application of clinical ethics.

Right For A Good Quality Care

Access to health care services should be provided without discrimination regarding race, religion, sex, national origin, or disability. Patients should also be free from discrimination on the basis of their disease, with respect to both employment and health insurance accessibility. Optimal treatment of a disease should be provided by a team that includes multidisciplinary medical expertise. Patients should also have access to counseling for their psychosocial, nutritional, and other needs. Patients should be offered the opportunity to participate in relevant clinical trials, and should have access to innovative therapies, which may improve their disease outcome.

Right For Informed Consent And Choice Of Treatment

Patients should be empowered to participate in decision making, and the health care team should respect those decisions. Any unauthorized touching of a person is battery, even in the medical setting. The patient’s consent allows the physician to provide care.

Consent may be either expressed or implied. Expressed consent most often occurs in the hospital setting, where written or oral consent is given for a particular procedure. In many medical encounters, when the patient presents to a physician for evaluation and care, consent can be presumed. The underlying condition and treatment options are explained to the patient and treatment is rendered or refused. In medical emergencies, consent to treatment that is necessary to maintain life or restore health is usually implied unless it is known that the patient would refuse the intervention.

The doctrine of informed consent goes beyond the question of whether consent was given for a treatment or intervention. Rather, it focuses on the content and process of consent. The physician is required to provide enough information to allow a patient to make an informed judgment about how to proceed. The physician’s presentation should be understandable to the patient, should be unbiased, and should include the physician’s recommendation. The patient’s or surrogate’s concurrence must be free without coercion.

The principle and practice of informed consent rely on patients to ask questions when they are uncertain about the information they receive; to think carefully about their choices; and to be forthright with their physicians about their values, concerns, and reservations about a particular recommendation. Once patients and physicians decide on a course of action, patients should make every reasonable effort to carry out the aspects of care that are in their control or to inform their physicians promptly if it is not possible to do so.

The physician is obligated to ensure that the patient or the surrogate is adequately informed about the nature of the patient’s medical condition and the objectives of, alternatives to, possible outcomes of, and risks involved with a proposed treatment.

All adult patients are considered competent to make decisions about medical care unless a court declares them incompetent. In clinical practice, however, physicians and family members usually make decisions without a formal competency hearing in the courts for patients who lack decision-making capacity. This clinical approach can be ethically justified if the physician has carefully determined that the patient is incapable of understanding the nature of the proposed treatment; the alternatives to it; and the risks, benefits, and consequences of it.

Most adult patients can participate in, and thereby share responsibility for their health care. Physicians cannot properly diagnose and treat conditions without full disclosure of patients’ personal and family medical history, habits, ongoing treatments (medical and otherwise), and symptoms. The physician’s obligation to confidentiality exists in part to ensure that patients can be candid without fear of loss of privacy. Physicians must try to create an environment in which honesty can thrive and patient concerns and questions are elicited. Patients should have access to a second opinion and the ability to choose among different treatments and providers.

Right For Access To Information And Clear Disclosure

Patients should receive adequate information about their illness, possible interventions, and the known benefits and risks of specific treatment options. They should have the ability to ascertain names, roles, and the qualifications of those who are treating them.

To make health care decisions and work intelligently in partnership with the physician, the patient must be well informed. Effective patient–physician communication can dispel uncertainty and fear and can enhance healing and patient satisfaction. Information should be disclosed whenever it is considered material to the patient’s understanding of his or her situation, possible treatments, and probable outcomes. This information often includes the costs and burdens of treatment, the experience of the proposed clinician, the nature of the illness, and potential treatments.

Even if it is sometimes uncomfortable to clinician or patient, information that is essential to the patient must be disclosed. How, when, and to whom information is disclosed are important concerns that must be addressed.

Information should be given in terms that the patient can understand. The physician should be sensitive to the patient’s responses in setting the pace of disclosure, particularly if the illness is very serious. Disclosure should never be a mechanical or perfunctory process. Upsetting news and information should be presented to the patient in a way that minimizes distress. If the patient is unable to comprehend his or her condition, it should be fully disclosed to an appropriate surrogate. In addition, physicians should disclose to patients information about procedural or judgment errors made in the course of care if such information is material to the patient’s well-being.

Right For Confidentiality

Confidentiality is a fundamental tenet of medical care. It is a matter of respecting the privacy of patients, encouraging them to seek medical care and discuss their problems candidly, and preventing discrimination on the basis of their medical conditions. The physician must not release information without the patient’s consent (often termed a “privileged communication”). However, confidentiality, like other ethical duties, is not absolute. It may have to be overridden to protect individual persons or the public – for example, to warn sexual partners that a patient has syphilis or is infected with HIV – or to disclose information when the law requires it. Before breaching confidentiality, the physician should make every effort to discuss the issues with the patient. If breaching confidentiality is necessary, it should be done in a way that minimizes harm to the patient and that regards the applicable country law.

Confidentiality is increasingly difficult to maintain in this era of computerized record keeping and electronic data processing, faxing of patient information, third-party payment for medical services, and sharing of patient care among numerous medical professionals and institutions. Physicians should be aware of the increased risk for invasion of patients’ privacy and should help ensure confidentiality. Within their own institutions, physicians should advocate policies and procedures to secure the confidentiality of patient records.

Discussion of the problems of an identified patient by professional staff in public places (e.g., in elevators or in cafeterias) violates confidentiality and is unethical. Outside of an educational setting, discussions of a potentially identifiable patient in front of persons who are not involved in that patient’s care are unwise and impair the public’s confidence in the medical profession. Physicians of patients who are well known to the public should remember that they are not free to discuss or disclose information about a patient’s health without the explicit consent of the patient.

In the care of the adolescent patient, family support is important. However, this support must be balanced with confidentiality and respect for the adolescent’s autonomy in health care decisions and in relationships with health care providers. Physicians should be knowledgeable about state laws governing the right of adolescent patients to confidentiality and the adolescent’s legal right to consent to treatment.

Occasionally, the physician receives information from a patient’s friends or relatives and is asked to withhold the source of that information from the patient. The physician is not obliged to keep such secrets from the patient. The informant should be urged to address the patient directly and to encourage the patient to discuss the information with the physician. The physician should use sensitivity and judgment in deciding whether to use the information and whether to reveal its source to the patient. The physician should always act in the best interests of the patient. Confidentiality should be respected during the life and even after death, unless authorization of the patient.

Right For Access To Medical Records

Patients should be permitted to review their medical records and obtain copies for free or for a reasonable fee. Health care providers should be available to explain the contents of medical records to patients.

Medical records and other patient-specific information, including genetic information, should be regarded as private except to the extent that they are required to be shared for treatment or payment purposes. If access to patient-specific information is necessary for research, patients should be given the opportunity to agree.

Rights Of Nonconscious Or Incapacitated Patient

When a patient lacks decision-making capacity (i.e., the ability to receive and express information and to make a choice consonant with that information and one’s values), an appropriate surrogate should make decisions with the physician.

Ideally, surrogate decision makers should know the patient’s preferences and act in the best interests of the patient. If the patient has designated a proxy, as through a durable power of attorney for health care, that choice should be respected. When patients have not selected surrogates, standard clinical practice is that family members serve as surrogates. Some states designate the order in which family members will serve as surrogates.

Physicians should be aware of legal requirements in their state for surrogate appointment and decision making. In some cases, all parties may agree that a close friend is a more appropriate surrogate than a relative.

Physicians should take reasonable care to ensure that the surrogate’s decisions are consistent with the patient’s preferences and best interests. When possible, these decisions should be reached in the medical setting by physicians, surrogates, and other caregivers.

Physicians should emphasize to surrogates that decisions should be based on what the patient would want, not what surrogates would choose for themselves. If disagreements cannot be resolved, hospital ethics committees may be helpful. Courts should be used when doing so serves the patient, such as to establish guardianship for an incompetent patient, to resolve a problem when other processes fail, or to comply with the country law if it exists.

Right For Information, Health Education, And Prevention

Individuals should be advised with respect to the prevention of diseases (communicable and noncommunicable diseases, cancer, etc.) and should be provided any preventive interventions that are evidence based and available. This can be performed, for example, under the services/programs of health prevention, health protection, screening, and early detection.

Right For Human Dignity

Patients should be treated with dignity at all times (Daher 2010). Quality care in cancer and other debilitating and chronic diseases requires pain, palliative, and supportive care, including the use of opioid analgesics and other symptoms management, for conditions induced by the treatment or by the disease itself (Brennan 2007; European Guidelines for Cancer Patients’ Rights).

During the whole process, the health professionals should respect the autonomy of the patient and help him to overcome fear, pain, and suffering and with control of pain and other symptoms in order to provide the best quality of life possible (Daher 2010; Daher and Hajjar 2014). At all times the patient will be asked for informed consent when decisions on the use of life-sustaining treatment are needed (Erer et al. 2008).

Cancer survivors should be provided a comprehensive care summary and follow-up plan at the completion of primary therapy. They also should be systematically monitored for the long-term and late effects of treatment and eventual rehabilitation.

Right For Spiritual Assistance

Religious belief and the teachings of various faith communities are relevant to medical care. Religion offers powerful perspectives on suffering, loss, and death. The majority of people (especially in communities like ours in Middle Eastern countries) profess some form of religious belief. Also, many persons from different cultures are deeply committed to their religious traditions.

Experience reveals the value of religious belief in times of sickness and death. Religious counselors and chaplains have an important role to play in health care. Nevertheless, many physicians respect the tenets of their own religion and allow them to influence their practice of medicine.

Ethical Dimension Of Patients’ Rights

The traditional physician–patient relationship can be summarized as follows: Sick patients ask physicians to help them get better and physicians profess to be morally committed and technically competent to help the sick. In order to honor this contract, attention to ethical issues in clinical medicine has increased in recent years as a result of profound changes both in medicine and society. Among the many factors causing the increased prominence of ethics in medicine are unprecedented growths in scientific knowledge, expansion in the availability and efficacy of medical technologies, a more equal relationship between patients and physicians, new organizational arrangements in the provision of services, and increased pressure to contain spiraling costs.

It is essential that patients’ rights and clinical ethics move in the same direction. The principles of ethics currently embraced by the medical profession include the following: (a) autonomy refers to respect for a person’s self-determination, alluding to a patient’s wishes regarding treatment choice; (b) beneficence means doing good to patients; (c) fidelity emphasizes faithfulness to a physician’s duties and obligations; (d) justice dictates that a physician’s decision on patient treatment is made fairly and impartially; and (e) utility implies that a physician’s actions should yield good results, achieving maximum benefits for the patient without wasting resources (Pellegrino 1978; Siegler et al. 1990).

Conclusion

Patients’ rights as a field of study have gained attention in the recent years worldwide, especially in developed communities. This is not the case in many developing or less developed countries. The literature on human rights and patients’ rights in these communities should be addressed.

For adequate fulfillment of patients’ rights, much work is required. There are many challenges, including, but not limited to: (a) flexible and creative public policies, (b) greater awareness of patients and their family about their rights and duties, (c) ongoing advocacy, (d) comprehensive education, (e) professional leadership, and (f) continued emphasis on compassion for this vulnerable group of people.

Among the practical recommendations that one can suggest are the following: (1) ensure constitutional endorsement of the right to health, (2) specify government obligations in social welfare, (3) provide health care services with emphasis on vulnerable groups, (4) incorporate a rights based approach in national policies, (5) collect statistics with monitoring, and (6) report regularly on progressive realization of the right to health and create legal instruments for enforcement (Gruskin 2006; Office of the High Commissioner of the Human Rights 2008; WHO n.d.).

Patients have the right to be treated and dealt with in a humane and respectful manner. Health care providers are urged to pay careful attention to this vital aspect of clinical management; they must keep the welfare and the rights of the patient above any other consideration.

Bibliography :

- Asher, J., Hamm, D., & Sheather, J. (2007). The right to health: A toolkit for health professionals (1st ed.). London: British Medical Association.

- Brennan, F. (2007). Palliative care as an international human right. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 33(5), 494–499.

- Daher, M. (2010). Pain relief is a human right. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 11(MECC Supplement), 91–95.

- Daher, M., & Hajjar, R. (2014). Palliative care for cancer patients in Lebanon. In M. Silbermann (Ed.), Palliative care to the cancer patient (pp. 125–140). New York: Nova Sciences.

- Erer, S., Atici, E., & Erdemir, A. D. (2008). The views of cancer patients on patient rights in the context of information and autonomy. Journal of Medical Ethics, 34(5), 384–388.

- European guidelines for cancer patient rights [Internet]. 2010. Available from: http://www.ecpc-online.org/advocacytoolbox/patients-rights.html

- Fine, R. (2005). From Quinlan to Schiavo: Medical, ethical, and legal issues in severe brain injury. BUMC Proceedings, 18, 303–310. www.mabookan.com/ka/ karen-quinlan-ethical-health-issue-pdf.html

- Gruskin, S. (2006). Rights-based approaches to health: Something for everyone. Health and Human Rights, 9(2), 5–9.

- Mpinga, E. K., Verloo, H., London, L., & Chastonay, P. (2011). Health and human rights in scientific literature: A systematic review over a decade (1999–2008). Health and Human Rights, 13(2), 1–28.

- Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), & World Health Organization (WHO) (Eds.). (2008). The right to health. Geneva: United Nations (OHCHR & WHO).

- Pellegrino, E. D. (1978). Ethics and the moment of clinical truth. JAMA, 239, 960–961.

- Schloendorff, M. E., Appellant, v. The Society of the New York Hospital, Respondent; Court of Appeals of New York 211 N.Y. 125; 105 N.E. 92; Decided 14 April 1914. http://wings.buffalo.edu/bioethics/schloen0.html

- Sheldon, G. F. (1998). Professionalism, managed care and the human rights movement. Bulletin of the American College of Surgeons, 83, 13–33.

- Siegler, M., Pellegrino, E. D., & Singer, P. A. (1990). Clinical medical ethics: The first decade. The Journal of Clinical Ethics, 1, 5–9.

- Veatch, R. M. (Ed.). (1997). Medical ethics (2nd ed., pp. 6–10). Boston: Jones & Bartlett.

- (n.d.). The right to health [Internet]. Available from:http://www.who.int/hhr/Right_to_health-factsheet.pdf

- Asher, J. (2004). The right to health: A resource manual for NGOs (1st ed.). London: International Federation of Health and Human Rights Organisations.

- The Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights. http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=31058&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html

- The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). www.ohchr.org/EN/UDHR/Pages/Introduction.aspx

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.