This sample Corporate Crimes and the Business Cycle Research Paper is published foreducational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing yourassignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic ataffordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

This research paper examines the (in fact only partial) Global Financial Crisis and its possible universal and differential direct impacts on frauds and on corporate crimes of various kinds and on control responses which, as routine activities perspectives would suggest, should have an impact upon financial and corporate crime levels. The paper examines the limited evidence about reporting processes and argues that some frauds whose commission long preceded the crisis will be brought into victim and/or public consciousness as a result of the credit squeeze; some “organized criminals” may be drawn into greater confidence in making fraud participation offers to insiders or blackmailing them because of the latter’s inability to repay debts and because they believe that people are more corruptible at times of economic stress; some fraud opportunities linked to workplaces will be reduced because if people motivated to defraud have lost their jobs, they can no longer commit internal frauds, but in other cases, temptations are greater because of the desire not to lose lifestyle and social status. The net effect of changes in guardianship, motivations, and opportunities is difficult to determine, and most fraud data – other than plastic card fraud – are too dependent on changing probabilities of recognition, reporting, and recording to enable confident inferences about trends to be drawn. It seems plausible that more “slippery slope” insolvency frauds occur in times of recession, as some company directors and professionals seek to preserve income and wealth from the economic consequences of the downturn. On the other hand, a bonus-driven culture makes “strain” a perpetual condition irrespective of the business cycle. There is no evidence that the GFC has had or is likely to have a major impact on increasing the cost of fraud or levels of fraud overall in the areas about which we have the best data and knowledge: North America, the UK, and Australia.

Background

This research paper reviews the relationship between economic cycles and a variety of white-collar and corporate crimes. This is not an area that has received very much criminological attention. An established criminological tradition examines the connection between economic crises and crime generally (Deflem 2011). In the early days, it was influenced by Marxist analysis of the endemic crises of capitalism, commencing with the work of Bonger (1916) and including some early empirical work by Radzinowicz (1939). Box (1987), anticipating later work on inequality and crime, argued that the significance of unemployment will vary depending on its duration, social assessments of blame, previous experience of steady employment, perception of future prospects, comparison with other groups, etc. Hence, there is likely to be a causal relationship between relative deprivation and crime, particularly in subcultures where unemployment is perceived as unjust and hopeless by comparison with the fortunes of other groups. Hale (1998) argued that increased opportunity or availability of targets had a long-run relationship with property crimes, while unemployment had a short-run impact on property crimes via its impact on motivating offenders. Arvanites and Defina (2006) showed that the strong economy of the 1990s reduced all four index property crimes and robbery by reducing criminal motivation. Business cycle growth produced no significant opportunity effect for any of the crimes studied. Cleck and Chiricos (2002) found that opportunity levels were generally unrelated to property crime rates and do not appear to mediate the unemployment-crime relationship. Of these authors, only Box looked at corporate crimes, arguing that recession motivated more corporate crimes for survival.

In a review of the evidence that was conducted in the wake of the previous Australian recession, Weatherburn (1992: 8) concluded that:

[T]here would appear to be no reason to expectthe criminogenic effects of sustained economic deprivation to be any quicker todissipate than they were to arrive…. Uncontrolled and rapid economicdevelopment, chronically high levels of unemployment in certain sectors of theeconomy, and the existence of a marginalised under-class of individuals andfamilies living in poverty are all conditions which can just as easily be foundin booming as in contracting economies…. Nothing could be more inimical tolaw and order than an economy which generates rapidly rising living standardsfor some and an abundance of criminal opportunities for the remainder.

Turning to white-collar crimes – broadly construed – its relationship with economic cycles has been examined less directly, via unemployment or strain theory, using data from before the most recent severe economic downturn, which most closely resembles the 1930s (when both criminal justice action and the nature of the economy were markedly different). Langton and Piquero (2007) thoughtfully examined the relationship of general strain theory and white-collar crimes of different levels of complexity, finding that the relationship varied for different sorts of offenses. Schoepfer and Piquero (2006: 223–234) found that

more unemployment was associated with less andnot more embezzlement [measured by recorded crimes from the UCR]. Though notnecessarily as expected by IAT [institutional anomie theory], this negativeeffect, however, would be inline for most forms of white-collar crime,including embezzlement, since employment provides the opportunity foroffending. Hence, this effect makes sense within the context of this particularcrime type (e.g. white-collar crime).. .. higher rates of polity weakened theeffect of unemployment on embezzlement.

However, the growth and globalization of financial instruments and industrial production of this century may have altered the relationship, and further work needs to be done on understanding economic cycles and corporate crimes, bearing in mind the immense problems of data validity.

The Global Financial Crisis And Financial/Corporate Crimes

There are at least two ways of examining the relationship between corporate/financial crimes and economic cycles, most recently the Global Financial Crisis whose effects, though not whose fundamental causes, were first strongly felt in 2007–2008. One is to look at the extent to which financial crimes (e.g., in the subprime mortgage issuance market and/or in the bundling of these and other derivatives into financial instruments like Collateralized Debt Obligations – CDOs) influenced the financial crisis (Braithwaite 2010; Nguyen and Pontell 2010). Another is to review the impact that the crisis has had and might plausibly have on financial and corporate crimes. It is the latter, possibly less exciting, issue that will be explored in this research paper. One aspect of this is the impact on public sentiments and government managerial reaction to corporate crimes generally and to subsets of financial crimes in particular (see, e.g., Levi 2009). There are many forms of corporate crime, which have different impacts and offender backgrounds, and about whose prevalence and incidence we have variable information. These are outlined below:

Types of Economic Crime

1. Harm government/taxpayer interests

2. Harm all corporate as well as social interests

• That is, systemic risk frauds that undermine public confidence in the system as a whole, domestic and motor insurance frauds, maritime insurance frauds, payment card and other credit frauds, pyramid selling of money schemes, and high-yield investment frauds

3. Harm social and some corporate interests but benefit other “mainly legitimate” ones

• Some cartels, transnational corruption (by companies with business interests in the country paying the bribe)

4. Harm corporate interests but benefit mostly illegitimate ones

• Several forms of intellectual property theft – sometimes called “piracy” – especially those using higher quality digital media

There are additionally many corporate crimes such as environmental crimes (Gibbs et al. 2010) or “safety crimes” (Tombs and Whyte 2007) that involve occupational deaths and diseases but that are not easily connected empirically to the Global Financial Crisis, though they are plausibly connected to changes in the cycle of industrialization and rates of profitability in the Global North and in the globalized supply chain from the Global South to North (and, increasingly, within the Global South and the BRICS): as, for example, in the shift from industrial production to financial and other services. This also has implications for individual national statistics, since as industrial production has shifted to Asia, the industrial safety records of Asian countries – which often are not readily available or verifiable – can be expected to worsen and that of Western economies to improve, even if the inspection of factories and extractive industries were equivalent, which they are not. Thus it may look as if there has been no effect of the crisis on health and safety in North American and Western Europe, and indeed, it is not obvious what health and safety regulators in the Global North can do about industrial deaths in China, except to impose production chain corporate criminal liabilities.

A key aim of this research paper is to examine what the evidence is that would enable us to judge what has happened and what is plausibly likely to happen to financial and corporate crimes in the context of what is often referred to as the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) – though as it transpired, it has not dramatically affected Australia, China, Singapore, or much of South America – whether as a result of that crisis or as a result of other factors that coincide with it. The Australian banking system was less hard-hit than elsewhere, to the extent that it briefly overtook the USA to take second spot after the UK as a financial services heavyweight, with the only net positive score among the leading countries in the Financial Development Index; by 2011, initial public offering (of securities) activity and insurance enabled Hong Kong SAR to overtake the United States and the United Kingdom to top the index (World Economic Forum 2012).

Research has reviewed general corporate crime data in the USA, including the effects of general and specific industrial prosperity. Using the original dataset of Clinard and Yeager from the mid-1970s, Wang and Holtfreter (2012) suggest that the effect of corporation-level strain is more pronounced for corporations marked by lower levels of diversification and corporations that operate in industries experiencing higher levels of strain. They found no evidence of corporation-level strain on violations; that corporations in rapidly growing, but not decaying, industries had higher violation rates; that the effect of corporation-level strain was less pronounced in corporations characterized by a higher level of diversification; that financially strained corporations had even higher violation rates in industries experiencing a decline in their financial performance; and that corporations experiencing growth in financial performance had higher violation rates in rapidly growing industries. Finally, they found no support that financially strained corporations had by far higher violation rates in industries characterized by more prevalent corporate illegality. Their work contains a solid review of general evidence on strain and corporate crime, though it is worth noting that the financial services sector is not singled out and had far less significance in the 1970s compared with this century.

The primary focus will be in areas where at least some reasonably valid data are available which, unfortunately, are mostly related to volume frauds in the private and public sectors rather than to management frauds and crimes by corporations, and care should be taken about generalization elsewhere. Thus, to the extent that measures against the financial crisis in general and fraud/corruption in particular have an impact on development aid and on opportunities for world trade, they might directly or indirectly stimulate or suppress fraud/grand corruption in developing countries: but data are not available to examine seriously that proposition. Other kinds of corporate crime data – for example, health and safety and/or environmental crimes – might be interesting to correlate with economic trends, but the research base is underdeveloped. It seems plausible that marginalized firms would be the most likely ones to commit not just frauds but also to cut corners on worker safety, consumer safety, and waste dumping. However, in a bonus-driven culture with predatory venture capitalist firms and short-term securities holdings, squeezed margins may be a sufficient condition, but they are by no means a necessary condition for corporate crime. The conventional wisdom attributes the rise of fraud to the impact of globalization, but “globalization” is insufficiently linear or specific to be useful as an explanatory variable. Black (2010) is critical of white-collar criminology’s shift since Sutherland from elite corporate misconduct and what he terms “control frauds” to more blue-collar embezzlement and frauds since Cressey’s time, and though it is arguable that criminology should cover both these areas, it is indeed important to remember what forms of business crimes one is examining, however they are labeled.

Estimating Financial Crime Costs

Despite all the victimization surveys that have been carried out in Australia, Europe, and the USA, and to a far lesser extent elsewhere, the collection of information on impacts (beyond reporting and “confidence in the police”) has been quite crude and simplistic. Moreover, harm (and threat) is not just about how much things cost us. “Organized fraud,” for example, intermingles actual impacts with the social construction of malevolence and “dangerous groups.” But what if we do not know whether or not particular fraudsters are connected with “organized crime groups” or are financing terrorism? Should we take the agnostic position that they are not connected and therefore are less harmful than they would have been? And why should having such connections be worse than the frauds of schemers like Bernie Madoff who stole roughly $15 billion from a variety of charities and relatively wealthy individuals and firms over a 15-year period, despite numerous attempts to alert the authorities?

Zemiology – the study of social harms – has been treated as a useful tool with which to batter the obsessions of conventional criminology with household and street crimes: the aim of some of its advocates is to transform our priorities so that we might do more about road and industrial accidents than about terrorism and perhaps more about corporate food poisoning than about what is normally thought of as criminal poisoning.

However, Sparrow (2008) emphasizes that it is absurd to neglect the relevance of perceptions of future dangerous intentions (as in “Islamic violence” post 9/11) when assessing harm, for this is part of their cultural impact and also ought to trigger our strategic interventions. It is arguable that we should not ignore planned (and foreseeable unplanned) harm doing in constructing risk assessments and crime control methodologies, however problematic politically it may be to incorporate such crime risk elements into general social planning (Dorn and Levi 2006; Edwards and Levi 2008). But irrespective of the current operational use of harm data, the latter (and crime seriousness studies) remain sociologically interesting and socially important.

Many estimates of fraud and money laundering are based on very limited evidence, derive from institutional profile raising, and take on a life of their own as “facts by repetition,” seldom critiqued either by media always hungry for sensational headlines (Levi 2006) or by pressure groups. On the other hand, if we rely on cases brought to conviction, the data may be absurdly low in both harm caused and case complexity, the most subtle cases of fraud and money laundering being hardest to prove beyond a reasonable doubt in the minds of juries or judges. We must be careful to avoid “throwing the baby out with the bathwater” by using only very low figures from convictions and treating them as “the figures” rather than just as validated minimum figures (see Levi and Burrows 2008).

The elapsed time from fraud to discovery and then from discovery to criminal justice action (if any) means that many of the larger frauds coming to light in 2008–2013 will have been committed some years before. One classic notable example is the Madoff’s long-running Ponzi scheme (van de Bunt 2010) though this was atypically long for this type of investment fraud. Although such schemes all come to an end eventually when incoming funds are insufficient to meet current payments, the link with the economy is that drops in confidence and increases in need for funds derail the criminal business model. In some other cases where fraud has been alleged, only careful case-by-case examination can enable us to understand when the fraud began in relation to the business cycle: but one might expect the frauds to result from a combination of ambitious expansion plans with unexpected reductions in business opportunities and/or cash flow. This time attrition for frauds differs from “volume crimes” such as credit and debit card fraud, which usually come to light promptly (though seldom as promptly as burglaries and vehicle thefts).

Normally, we would look to statistical data on recorded/surveyed crime and/or cost of crime trends to enable us to judge whether a problem is getting better or worse. However, as will be seen, even in the best countries, fraud data are quite poor, and this is an area that requires some redress if empirical criminology is not to continue to neglect white-collar crimes (see, more generally, Simpson and Weisburd 2009). Despite activities in train to improve government fraud statistics in the UK (Levi and Burrows 2008; NFA 2012) and in Australia, but not yet in the USA, these recent improvements cannot be applied retrospectively to past data. Payment card fraud data have the advantage that there is little time lag from crime to discovery, but in higher value management frauds and cartels – which arguably are far more serious – there typically is a much longer time before detection and even longer for criminal justice outcomes, if any: so any given year’s data will be a mix of crimes occurring at very variable years. This is a particular problem for evaluating the impact of economic trends, and there has been no opportunity here for the individual case analysis that would be a desirable alternative to aggregate data. Some safety crimes have immediate impacts, but environmental and industrial diseases may take years to emerge.

Australian fraud data are only intermittently available (Levi and Smith 2011; ABS 2012) and therefore cannot be “trended” without unacceptable speculative leaps. In the USA, very little effort has been made to generate better fraud data outside the populist consumer area of “identity theft” (Langton 2011), whose direct costs to the 5 % of the adult US population victimized over a 2-year period were estimated at $17 billion in 2008 (Langton and Planty 2010). The UK National Fraud Authority is seeking to make costs of fraud data annual, and the current estimate of the costs of fraud is £73 (US$118) billion (Levi et al. 2007; Levi and Burrows 2008; NFA 2012). Currently, however, reliable time series cost data are available in the UK only for payment card and check frauds, some aspects of identity frauds, and for external frauds against government departments and local authorities. No similar efforts have been conducted in other countries around the world, and fraud cost and incidence surveys carried out by Ernst & Young, KPMG, Kroll, and PwC in many parts of the world are both intermittent and have been applied only to large corporate victims, who are their primary clients and target markets for awareness raising (Levi et al. 2007; Levi and Burrows 2008). Indirect costs have not been examined seriously in any of these studies. Finally, there are the usual problems of whether it is possible to place within the category of fraud acts and actors that have not yet been subject to any criminal justice verdict: the “no-fault” settlement in 2010 of the action for civil fraud against Goldman Sachs by the Securities and Exchange Commission being a case in point (Dorn and Levi 2011). Such elite cases pose questions about the limitations of the relationship between crime and social harm and, if included as “fraud,” would have a dramatic effect on the composition of the dependent variable. If we take the effort to collect data as an indicator of what information the state considers important, as Jeremy Bentham intended criminal statistics to be in the nineteenth century, one inference is that fraud data are plainly considered unimportant by most governments most of the time, both to inform their resource allocation decisions and for public information about levels of “crime.” (Some skeptics may believe that this is a conspiracy to keep white-collar crimes out of the public eye, but there is no evidence for this proposition).

Identity Theft And Fraud

Identity frauds and their explanation are reviewed in detail elsewhere (Vieraitis et al. 2012). Here, we focus simply on trends. The Personal Fraud Survey for 2010–2011 (ABS 2012) found that Australians lost $1.4 billion due to personal fraud (which includes credit card fraud, identity theft, and scams). The survey results estimated that three in five victims of personal fraud (713,600 persons) lost money, an average of $2,000 per victim. Around 6.7 % of the population aged 15 years and over were a victim of at least one incident of personal fraud in the 12 months prior to interview. This is an increase from 5 % in 2007. The survey results show:

• 3.7 % (662,300) of Australians were victims of credit card fraud, an increase from 2.4 % in 2007.

• 0.3 % (44,700) of Australians were victims of identity theft, a decrease from 0.8 % in 2007.

• 2.9 % (514,500) of Australians were victims of scams, an increase from 2.0 % in 2007. These trends are demonstrated elsewhere (see http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/ Lookup/4500.0Chapter25July+2011+to+June+2012).

However, it seems unlikely that these trends are the result of the financial crisis, not least because this has not occurred in Australia, due to the more limited involvement of banks in the derivatives market and to the boom in extractive industries sales to Asia.

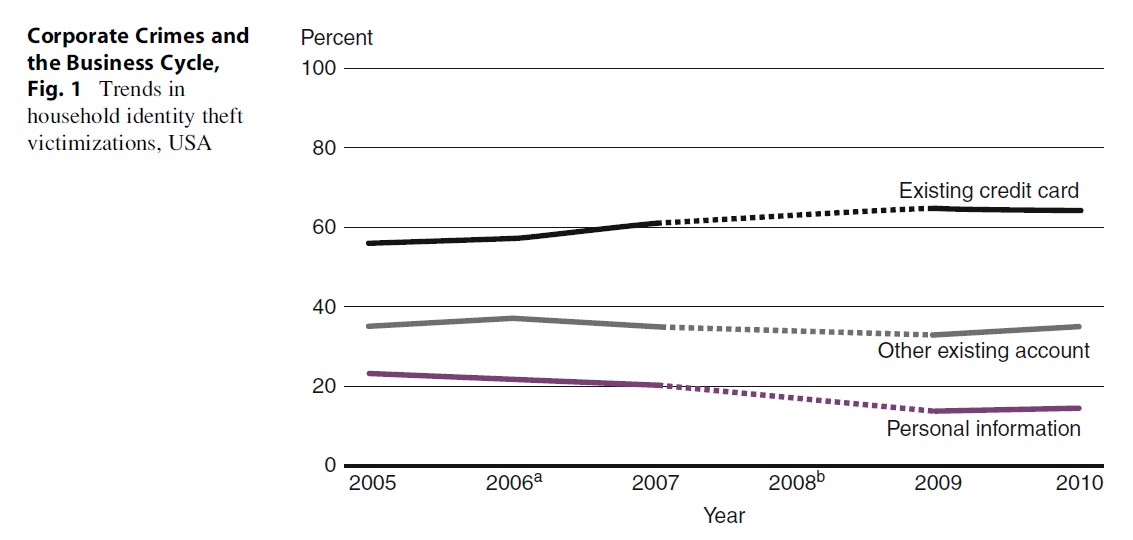

In the USA, trends inidentity fraud may be measured by victimization survey data, which show noobvious, consistent link with the business cycle. Below are the trends (Langton2011: 2) (Fig. 1):

In the UK, data collected by the not-for-profit fraud prevention service CIFAS indicated a rise in identity takeover frauds, as “new credit” became harder to get, generating displacement to impersonating existing account holders. Such frauds emerge quite quickly. In 2009–2010, applications containing lies or supplying false supporting documentation fell 23 %; the use of false identity details and cases where an innocent victim has had their identity details used fraudulently rose 10 % (CIFAS 2010). Since then, the frauds recorded on a collective industry database rose by a quarter in 2009 and remained relatively unchanged thereafter: they were 77,500 in 2007 and 113,250 in 2011 (CIFAS 2012). No equivalent data are available for any other countries, because no equivalent organizations exist there to integrate credit application data.

Payment Card And Allied Credit Frauds

Since 2006, UK payment card fraud data have displayed a broad downward trend in fraud on lost or stolen cards, due to the introduction of Chip and PIN in Europe, a more recent drop in counterfeit frauds on skimmed and cloned cards, which previously had risen substantially, mainly being used overseas to sidestep Chip and PIN controls. Total fraud losses on UK cards fell by 7 % between 2010 and 2011 to £341 million. This is the lowest annual total since 2000 and follows on from a fall of 17 % in 2009–2010. While card usage and transaction volumes continue to grow, card fraud losses against total turnover – at 0.06 % – continue to decrease and fell by 33 % in 2009–2011 (Financial Fraud Action UK 2012). More generally, payment card fraud in Europe increased after 2006, peaking in 2008. The levels in 2011 are €121 million more than in 2006. A notable exception is the UK, which accounted for 45 % of the total in 2006 and now accounts for 29 %, a reduction of €177 million. It appears that criminals have shifted their focus to new opportunities within Europe, as antifraud measures in the UK became stricter (FICO 2012).

In financial year 2006, card and check fraud in Australia totaled A$142.6 m.; by 2011, it had almost doubled to A$251.5 m. As a percentage of the total value of transactions over the same period, it doubled to 0.0132 % in 2011 (http://www.apca. com.au/payment-statistics/fraud-statistics/archivereleases/2011-financial-year). None of these Australian or UK changes have any obvious relationship to the GFC but are more readily explained by prevention actions and by the introduction of Chip and PIN in Australia (Levi and Smith 2011).

Canadian data for debit card fraud show that debit card frauds rose since the recession, before falling significantly in 2011 to where they were in 2005 – C$70 million – though with a lower average cost and much higher debit card use (http://www.interac.ca/media/stats.php, accessed 21 September 2012).

There are trend data in the report of the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC 2012: 3), showing a continuing rise in complaints since 2007 (and before), though identity thefts – which do not always result in frauds – have varied somewhat. For the 12th year in a row, identity theft complaints topped the list of consumer complaints in the USA. Of complaints filed in 2011, 279,156 (15 %) were identity theft complaints, compared with 86,250 (though a higher 27 % of complaints) in 2001.

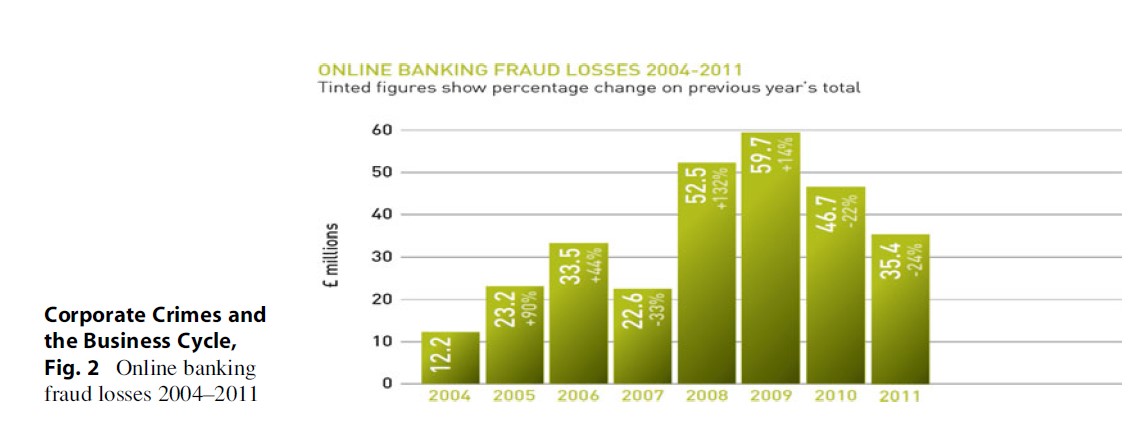

The fact that theupward trend long preceded the financial crisis shows the danger of examiningonly data after the date of the crash. They suggest a rising secular trend,though not self-evidently any particular reason. Rather they are consistentwith a dynamic model of routine activities theory within which both criminalactors and commercial crime preventers seek to maximize gains within theircapacity and minimize losses, respectively. This may be seen in banks’ onlineUK fraud losses (Financial Fraud Action UK 2012), which again show no particularcorrelation with the business cycle (Fig. 2).

Mortgage Frauds

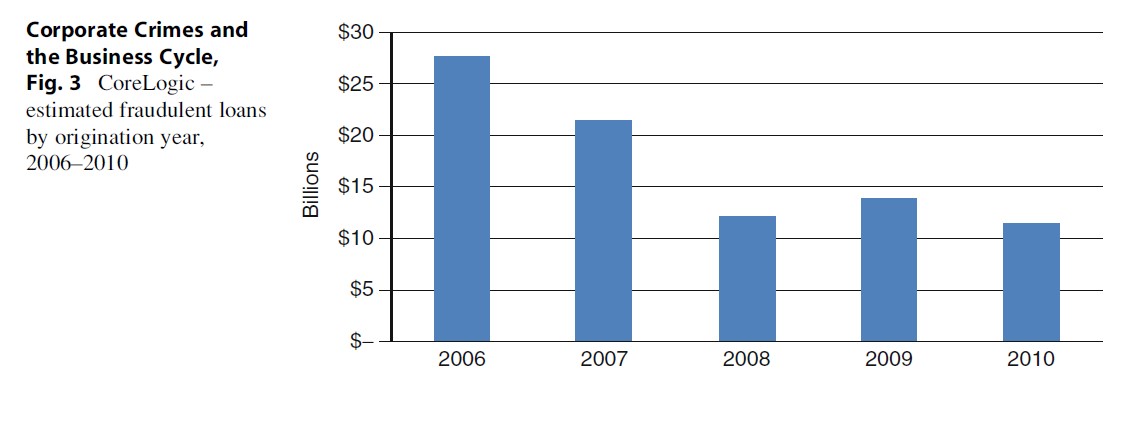

The FBI (2012) notesthat “during 2011, mortgage origination loans were at their lowest levels since2001, partially due to tighter underwriting standards, while foreclosures anddelinquencies have skyrocketed over the past few years. So, distressedhomeowner fraud has replaced loan origination fraud as the number one mortgage fraudthreat in many FBI offices. Other schemes include illegal property flipping,equity skimming, loan modification schemes, and builder bailout/condo conversion.During FY 2011, we had 2,691 pending mortgage fraud cases.” The mortgage fraudreport (FBI 2011) provides the following chart, neatly illustrating the declineof mortgage originations alongside the recession that they helped to generate(Fig. 3):

There is a laggedeffect of the fraud identification process, and the frauds began typicallybefore the financial crisis, though the general report usefully outlines theprecipitating factors behind the mortgage fraud crisis and suggests that the rateof deception accelerated as brokers sought to retain their commission bonusesin a falling market. (Though the latter is plausible, the data are not availableto demonstrate it). Many of the situational opportunities to defraud are fairlywidespread over time, so variation is likely to be accounted for in terms ofthe spread of techniques among the wider population, expectations of thecorruptibility of others, and changes in motivation, including the fear ofdownward economic mobility.

Control Frauds

“Control frauds” are seemingly legitimate entities controlled by persons who use them as a tool for fraud. Black (2010) argues that fraudulent lenders produce guaranteed, exceptional short-term “profits” through a four-part strategy: extreme growth (Ponzi-like), lending to uncreditworthy borrowers, extreme leverage, and minimal loss reserves. These false profits defeat regulatory controls and allow the CEO to convert the assets of the firm to his personal benefit through seemingly normal compensation mechanisms. The short-term profits also cause the CEO’s stock options holdings to appreciate. Each element of the strategy dramatically increases the eventual loss. The record “profits” allow the fraud to grow rapidly for years by making bad loans. The “profits” allow the managers to loot the firm through exceptional compensation, increasing losses.

Another example of much longer elapsed time from fraudulent to business-detected awareness is “rogue trading” in the form of illicit (and – perhaps more importantly – unsuccessfully!) betting on market trends, for example, by Nick Leeson at Barings in 1995 (http://www. nickleeson.com) and by Je´roˆ me Kerviel at Socie´te´ Ge´ne´rale in 2007–2008. (In 2010, Kerviel was imprisoned for his deceptions, despite his attempts to blame it on the bank management). In both cases, the primary accused alleged that more senior managers turned a blind eye to the risk taking, because they were incompetent (Barings) or because they stood to gain if the risks paid off (both Barings and Socie´te´ Ge´ne´ rale). The popular explanation for this (and other excrescences of the financial sector) is that it is caused by greed. However, unless it is a tautology, greed is not a helpful discriminator between those who both see and take fraud opportunities and those who do not. Some might argue that offenders and non-offenders are equally greedy, but that the latter are more risk averse by temperament/ social training/testosterone levels (Coates 2012). Nor is it obvious that “the recession” – local or global – had any impact at all on these sorts of alleged frauds, except indirectly, inasmuch as credit and controls tend to be tighter in recessionary times. In essence, they were cases in which ill-supervised traders found ways of breaching their dealing limits without detection and, having lost significant sums in early trading, carried on trading in the hope that they would be able to recoup those losses. Whether others behaved similarly but were more fortunate in their later dealing (or gambling) and remained forever undetected is unknown.

The Global Financial Crisis (GFC) And Its Economic And Social Impact

Australia was less affected by the GFC than were many other Western OECD countries such as the UK and the USA. Before looking at the implications for fraud, it might be helpful to see what the general financial crime-relevant effects might be expected to be. Institute for Fiscal Studies research (Muriel and Sibieta 2009) shows that low-skilled “elementary” occupations have suffered most since 2008 in the UK, followed by skilled trades and sales. In contrast, managers and senior officials have seen their unemployment increase by only 1 %, and “white-collar” professional unemployment has increased by just 0.7 %, about one sixth of the increase in the other groups. This does not mean that the “white-collar workers” are not fearful: but the impact of these fears on their propensity to defraud or launder money remains unresolved. The rise in unemployment among those with housing commitments and “negative equity” in their mortgaged homes constitutes a serious economic trap and could lead to increased personal bankruptcies and/or crime to support living standards. However, social security fraud and payment card fraud are the two types most readily open to such persons as criminal opportunities without significant skills barriers.

A demonstration that increased unemployment – whether generally or in a particular sector from which fraudsters came – always tended to be followed by increased crime rates would provide more compelling evidence of a causal relationship than would mere cross-sectional data for a particular point in time. However, it would have to overcome unreported and unrecorded fraud data problems, some but not all of which are being mitigated in the UK by the Action Fraud Reporting Centre, which is based partly on the USA and Canadian NWC3/ RECOL reporting centers, though these latter are more web than telephone based.

The GFC And Models Of Fraud Explanation

There has never been a simple link between recession, poverty, and crime. Barbara Wootton (1959) observed that if there were, then widows and elderly people would have the highest offending rates. Becker’s valuable contribution to the economic explanation of crime has been eroded over time by the understanding from behavioral economists that his individualistic focus on crime and rational choice is mistaken, since our beliefs about what other people are doing and will find socially acceptable significantly mediate our behavior and even our desires. The reaction of people to often dramatic changes in their financial circumstances and their social prestige (and in their expectations of unbroken progress toward “the good [consumer] life”) is a good test of the adequacy of criminological theories: in the particular case of white-collar crimes (see Simpson and Weisburd 2009), the anxieties among well-paid (and often highly wealth-oriented) professionals about the personal and corporate impact of the GFC gives plausible grounds for concern about what extra crime risks will be generated. These might take the form of greater willingness to trade off the risk of money-laundering prosecution against doing extra business. There is also the possibility that lower paid white-collar workers – for example, in call centers and banks – may be tempted to engage in fraud and money laundering on behalf of “organized crime” groups. These phenomena are not new: what is being proposed is that there may be a significant escalation in take-up of such opportunities.

Clarity is important here. To the extent that crimes are occupational, one must have an occupation in order to commit them. To illustrate this, we might examine the extent to which fraudulent chief executives such as Lord Conrad Black, Alan Bond, the chiefs of Enron, and “dot.com” bubble chiefs were able to allocate to the company expenditures that in fact were largely or wholly personal. If others have confidence in them, such entrepreneurs can develop new businesses that may generate new manipulative possibilities, but this would usually take longer at times of recession. At a lower level, staff in call centers (whether physically located in Western jurisdictions or in English-speaking South Asian countries) cannot so easily copy and extract personal data of account holders if they are no longer employed in the call centers. If still employed, they may be more tempted to defraud if they consider that they may shortly become unemployed and/or that the company will show no loyalty toward them. (Though their ability to offend may be reduced by physical opportunity controls such as the absence of USB and CD drives on computers and rapid integrity checks). Under such circumstances, voluntary compliance via procedural legitimacy (Tyler 2009) becomes much harder to achieve.

Knowledge of criminal techniques should be differentiated from opportunity and motivation to offend, though offending may be inhibited if people do not believe that they have enough knowledge to commit any particular sort of fraud that they contemplate. It is the expectation or fear that one may become unemployed, not post-employment status, that presents the extra risk here. There may be some crimes – computer hacking, for example – where employment status may be unimportant, though the importance of social engineering in getting passwords or other elements of crime may suggest that having a job in which one knows these current gateways is useful. (Past gateways may still be current if controls are not changed immediately when people are “let go”). Impacts of the GFC on professionals elsewhere may impact any country because, given international finance and trade – both for business and individuals – they may be the victims of frauds originating elsewhere, and expatriate professionals who lose their jobs may return home and exercise their skills illicitly. The greater time available to the unemployed in any country can give greater room for experimentation, and criminal attempts seldom are punished or even logged by targets or financial intermediaries.

The “crime triangle” of motivation, opportunity, and capable guardians can be applied to fraud, and it is here in human and technological changes to these parameters that one may search for an explanatory framework. A priori, it would appear that different skill sets, commercial/personal background, and formal qualifications will be needed for different fraud offenses, and the barriers to entry depend on the starting point of any given individual or network in relation to the practical opportunity and criminal justice obstacles that confront them. The longer and more intensive an investigation, the more likely it is that surveillance will generate an accurate model of interactions between players in the network. In most countries of the world, a distinction is made between “laissez faire” opportunities to set up and work in commerce and some restrictions applied to people who want to open or work in the financial services sector, largely on the grounds that the latter can directly steal funds from the public. It is important to understand such restrictions in a global context rather than the traditional nation-state perspective of regulation and criminal justice.

What some offenders are able to do is simply to deploy the range of global corporate mechanisms available in a free enterprise society where there are insufficient “capable guardians” to stop them misusing the disguises offered by the corporate form or the authority and power of a corporate role. Barry (2001) highlights the role played by Bond’s ingenuity and the (skillfully manipulated) delays of law in enabling him to exploit the rule whereby gifts “not for value” could be set aside only if they preceded bankruptcy by 2 years. The lawyers who enabled that delay were paid by generous international benefactor friends and by a Swiss who was alleged to have acted as a nominee for Bond, using a variety of foreign trust companies. Enron offered a dazzling array of special purpose vehicles to hide transactions: this was long before the GFC, and it is moot whether the impact on fraud of the crisis was affected by the SarbanesOxley and other supervision measures introduced in the aftermath (see Tillman 2009, for some insights).

Levels Of Indebtedness And Regulation

Corporate indebtedness is a major trigger for the revelation of fraud, as it becomes impossible to hide large-scale fraud (or at least to hide great loss, since it may be possible to misrepresent fraud as legitimate commercial failure among all the other corporate collapses, especially if creditors can be strung out long enough to risk “throwing good money after bad”). At the individual level, levels of indebtedness and illiquidity are major components that make some aspects of the current GFC different, and the reduction in lending capacity has affected the depth of the economic crisis. One would not want to overstress this – the great scammers of the 1980s were highly leveraged on their corporate assets and gave personal guarantees that turned out to be worthless (Barry 2001). However, not only are wealthy entrepreneurs of the current era (e.g., Russian “oligarchs”) highly mortgaged on their assets and therefore more pressurized to lie in order to stay afloat long enough to avoid a forced sale, but also a broad range of people in many walks of life are hugely indebted compared with the 1980s. The long period of prosperity is one reason for this, alongside the rising housing market that tempted many to borrow for current optional expenditure beyond their capacity to repay. Business, consumers, and regulators fell victim to the convenient myth that the “boom and bust” cycle had been abolished.

The rise in visible mortgage frauds (Carswell and Bachtel 2009; Nguyen and Pontell 2010) and in consumer/investment scams has energized the regulatory process, assisted by forensic linking software developments which make it easier proactively to search out connections between banking and insurance fraud networks. Since Ponzi investment pyramids rely on a high rate of incoming investments to sustain payouts, a fall in the rate of increase of investments or a reduction in the rate of reinvestment of imaginary profits causes them to collapse earlier.

Conclusions

The impact of the Global Financial Crisis upon fraud depends upon what one includes within the latter category. The damning verdict of the Valukas (2010) report into the factors leading up to the collapse of Lehman Brothers and the civil charges of fraud against Goldman Sachs by the Securities and Exchange Commission (treated as criminal by the media) make the fluctuating boundaries of fraud even more apparent (Dorn and Levi 2011). Frauds and white-collar crimes need to be broken down in conformity with the purposes for which one wants to use the typology, especially if a link to the business cycle is to be established.

In their powerful analysis of “animal spirits,” Akerlof and Shiller (2010) identify confidence, fairness, corruption and bad faith, money illusion, and stories as the key drivers of economic change, both positive and negative. As they acknowledge, their work is of a high level of generality, and to turn them into operationalizable models capable of correlating with financial crimes of various kinds is too major a task for this study (and plausibly for my lifetime). What seems plain is that generalizations about the correlation between economic crises and fraud (or other types of financial crime) are far too glib to be sustainable in the round. More limited evidence exists of some subsets of fraud, but even here, the recession serves to mask the complexity of trends, and once the lagged awareness, reporting, and investigation of larger frauds are taken into account, the relationship is shown to be less strong than it initially appeared. A working generalization is that the most serious financial frauds involving credit are “crimes of prosperity” at which time controls are relatively weak and borrowing is relatively easy. The fear of falling also acts as a stimulant to some of those who have the opportunity to defraud (Piquero 2012). In times of financial decline, when controls both on fraud and on the availability of fresh credit tighten, these long-term frauds are exposed, and this creates the appearance of their being “crimes of adversity.” Smaller scale volume frauds may be stimulated by factors relatively independent of the business cycle, but again the business cycle may provoke changes in the control environment which, alongside controller perceptions of the rate of change in risk, may lead to reductions in opportunity. It may be that biosocial elements influence animal spirits in the hour between dog and wolf (Coates 2012). But the relative lack of watchdogs and the absence of barking in the night or of prosecutions in the days since the financial crisis began should reasonably baffle those who see a great deal of routine prosecution of relatively trivial crimes elsewhere in the social system and who wonder why electronic surveillance and rapid response repression are only justified when elites are not under suspicion.

Bibliography:

- ABI (2009) General insurance claims fraud. Association of British Insurers, London, http://www.abi.org.uk/ Media/Releases/2009/07/40569.pdf

- ABS (2012) Personal fraud. 2010–2011. Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra, http://www.abs.gov. au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4528.0/

- Akerlof G, Shiller R (2010) Animal spirits: how human psychology drives the economy, and why it matters for global capitalism. Princeton University Press, Princeton

- Arvanites TM, Defina RH (2006) Business cycles and street crime. Criminology 44(1):139–164

- Barry P (2001) Going for broke. Bantam, Melbourne

- Barbara Wootton (1959) Social Science and Social Pathology (London: Allen and Unwin)

- Black W (2010) Epidemics of ‘Control Fraud’ lead to recurrent, intensifying bubbles and crises. http://papers. ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id¼1590447

- Bonger W (1916) Criminality and economic conditions. Little, Brown, New York

- Box S (1987) Recession, crime and punishment. Palgrave Macmillan, London

- Braithwaite J (2010) Diagnostics of white-collar crime prevention. Criminol Public Policy 9(3):621–626

- Carswell AT, Bachtel DC (2009) Mortgage fraud: a risk factor analysis of affected communities. Crime Law Soc Change 52:347–364

- CIFAS (2010) Figures reveal the bleak and complex reality of fraud in the UK today. http://www.cifas.org.uk/ default.asp?edit_id¼1048-57. Accessed 27 Nov 2010

- CIFAS (2012) Is identity fraud serious? http://www.cifas. org.uk/is_identity_fraud_serious

- Cleck G, Chiricos T (2002) Unemployment and property crime: a target-specific assessment of opportunity and motivation as mediating factors. Criminology 40(3):649–680

- Coates J (2012) The hour between dog and wolf: risk-taking, gut feelings and the biology of boom and bust. Fourth Estate, London

- Deflem M (2011) Introduction: criminological perspectives of the crisis. In: Deflem M (ed) Economic crisis and crime. Emerald Group, Bingley

- Dorn N, Levi M (2006) From Delphi to Brussels, the policy context: prophecy, crime proofing, impact assessment. Eur J Crim Policy Res 12:213–220

- Dorn N, Levi M (2011) Theorising the security and exchange commission’s 2010 settlement with Goldman Sachs: legislative weakness, reintegrative shaming or “temporary business interruption“ for financial market power elites? In: Antonopoulos G, Groenhuijsen M, Harvey J, Kooijmans T, Maljevic A, von Lampe K (eds) Usual and unusual organising criminals in Europe and beyond. Profitable crimes: from underworld to upper world. Liber amicorum Petrus C. van Duyne. Maklu Uitgevers nv, Antwerp

- Edwards A, Levi M (2008) Researching the organisation of serious crimes. Criminol Crim Justice 8(4):363–388

- FBI (2011) 2010 Mortgage fraud report: year in review. http://www.fbi.gov/stats-services/publications/mortgagefraud-2010/mortgage-fraud-report-2010

- FBI (2012) Financial crimes report to the public: fiscal years 2010–2011. http://www.fbi.gov/stats-services/ publications/financial-crimes-report-2010-2011

- FICO (2012) Evolution of card fraud in Europe. www. fico.com/fraudeurope

- Financial Fraud Action UK (2012) Fraud – the facts 2012. Financial Fraud Action UK, London

- FTC (2012) Consumer sentinel network data book January–December 2011. Federal Trade Commission, Washington, DC

- Gibbs C, McGarrell E, Axelrod M (2010) Transnational white-collar crime and risk: lessons from the global trade in electronic waste. Criminol Public Policy 9(3):543–560 Hale C (1998) Crime and the business cycle in post-war

- Britain revisited. Br J Criminol 38(4):681–698

- Langton L (2011) Identity theft reported by households: 2005–2010. Government Printing House, Washington, DC, http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/itrh0510. pdf

- Langton L, Piquero NL (2007) Can general strain theory explain white-collar crime? A preliminary investigation of the relationship between strain and select whitecollar offenses. J Crim Justice 35(1):1–15

- Langton L, Planty M (2010) Victims of identity theft: 2008 (NCJ 231680). http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/index. cfm?ty¼pbdetail&iid¼2222

- Levi M (2006) The media construction of financial white-collar crimes. Br J Criminol 46:1037–1057

- Levi M (2008) The phantom capitalists: the organisation and control of long-firm fraud, 2nd edn. Ashgate, Andover

- Levi M (2009) Suite revenge? The shaping of folk devils and moral panics about white-collar crimes. Br J Criminol 49(1):48–67

- Levi M, Burrows J (2008) Measuring the impact of fraud, a conceptual and empirical journey. Br J Criminol 48(3):293–318

- Levi M, Smith R (2011) Fraud vulnerabilities and the global financial crisis. Trends & issues in crime and criminal justice no. 422. Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra

- Levi M, Burrows J, Fleming M, Hopkins M (with the assistance of Matthews K) (2007) The nature. Extent and economic impact of fraud in the UK. Association of Chief Police Officers, London. http://www.cardiff. ac.uk/socsi/resources/ACPO%20final%20nature%20extent%20and%20economic%20impact%20of%20fraud.pdf

- Muriel A, Sibieta L (2009) Living standards during previous recessions. IFS Briefing Notes No. 85. http://www. ifs.org.uk/publications/4525

- NFA (2012) Annual fraud indicator. National Fraud Authority, London

- Nguyen TH, Pontell HN (2010) Mortgage origination fraud and the global economic crisis: a criminological analysis. Criminol Public Policy 9(3):591–612

- Piquero NL (2012) The only thing we have to fear is fear itself: investigating the relationship between fear of falling and white-collar crime. Crime Delinq 58(3):362–379

- Radzinowicz L (1939) A note on methods of establishing the connexion between economic conditions and crime. Sociol Rev 31(3):260–280

- Schoepfer A, Piquero NL (2006) Exploring white-collar crime and the American dream: a partial test of institutional anomie theory. J Crim Justice 34(3): 227–235

- Simpson S, Weisburd D (eds) (2009) The criminology of white-collar crime. Springer, New York

- Sparrow M (2008) The character of harms. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

- Tillman R (2009) Reputations and corporate malfeasance, collusive networks in financial statement fraud. Crime Law Soc Change 51:365–382

- Tombs S, Whyte D (2007) Safety crimes. Willan, Cullompton

- Tyler T (2009) Self-regulatory approaches to white-collar crime: the importance of legitimacy and procedural justice. In: Simpson, Weisburd (eds) The criminology of white-collar crime. Springer, New York

- Valukas A (2010) Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. Chapter 11 proceedings examiner’s report. http:// lehmanreport.jenner.com/

- Van de Bunt H (2010) Walls of secrecy and silence: the Madoff case and cartels in the construction industry. Criminol Public Policy 9(3):435–453

- Wang X, Holtfreter K (2012) The effects of corporationand industry-level strain and opportunity on corporate crime. J Res Crime Delinq 49(2):151–185

- Weatherburn D (1992) Economic adversity and crime. Trends and issues in criminal justice no. 40. Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra

- World Economic Forum (2012) The financial development report 2012. World Economic Forum, Davos

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.