This sample Crime Specialization, Progression, and Sequencing Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

This research paper describes what is known about three key dimensions of the active criminal career: frequency, specialization, and progression/ sequencing. Each of these topics is considered in terms of its theoretical implications and the empirical research that has been conducted on it. A great deal has been learned about these topics since they emerged early in the discussion of criminal careers. There are some questions about the ability to measure and assess them and the implications of doing so, however, and those are reviewed here as well.

Background On Dimensions Of Active Criminal Careers

The Study Of Criminal Careers

Understanding the criminal career is important as it can offer insight into the nature of offending generally and help in explaining the behavioral paths of offenders over time. This can, in turn, inform policy and practice that relates to career criminals as well as those who offend for only a limited period of time. The idea of a criminal career was raised in early life history research with delinquents. Later on, a report by Blumstein and colleagues (1986) outlined a number of relevant characteristics of criminal careers that might be described or explained by criminologists, and the idea of a criminal “career” became a conceptual framework against which empirical findings could be judged and theories could be developed (Piquero et al. 2003). This began a trend toward quantitative analysis of the dimensions of longterm careers in offending. Among those that were initially defined in that report or have received attention since are (a) the age of onset of careers, (b) the length and continuity in careers, (c) the process of desistance from criminal behavior, (d) the frequency of offending, (e) specialization or versatility in the types of offenses committed, and (f) progression of careers in terms of possible escalation or stepping down in the seriousness of offending. Each of these can serve as a touchstone for theory or policy/practice with respect to crime and criminality.

According to Smith et al. (1991:8), “the criminal career paradigm is not a theory of crime but rather a framework that permits more detailed study of criminal behavior and its causes by identifying dimensions of individual criminal careers.” One advantage of separating the dimensions of the criminal career is that criminological theories can be applied to a specific dimension (or dimensions), allowing theorists to be precise in their propositions. For example, one theory may explain why offenders become involved in criminal activity, while another may explain the variation in frequency among active offenders.

This research paper will focus on the last three dimensions of crime described above (frequency, specialization, and escalation), which are generally designated as dimensions of active criminal careers. Blumstein et al. (1986) asserted that high-frequency offenders were worthy of study from a career perspective because they “contribute disproportionately to the total measured number of crimes” (18). They also suggested that, within those careers, it is important to investigate questions of how crimes mixed and were arrayed as a possible means of better understanding offenders. This research paper first provides some definitions for these concepts before moving into a synthesis of what is known about them. That discussion also considers potential controversies or disagreements that have come up over time. Finally, some “open questions” in each of these areas are discussed in order to provide a sense of where research and practice might go in the future.

Dimensions Of The Active Criminal Career

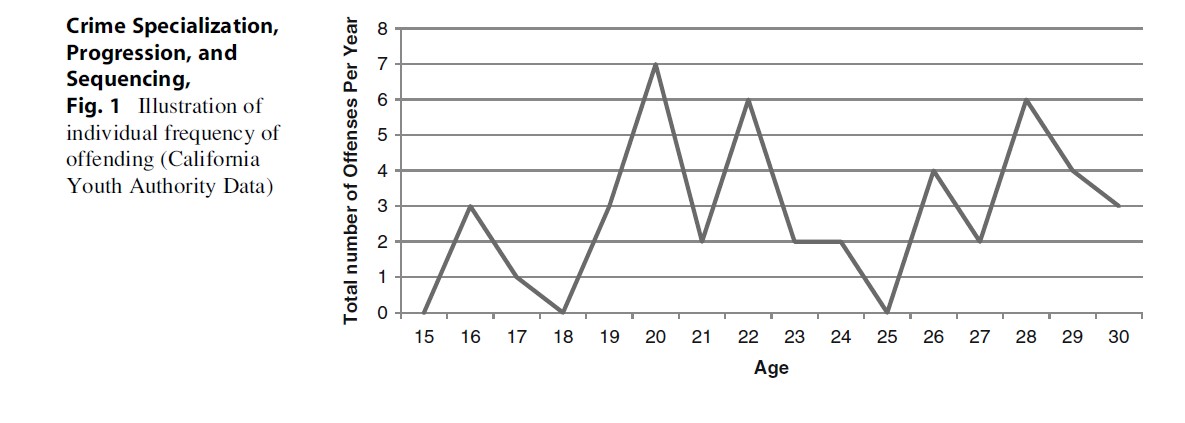

The dimensions of the criminal career discussed here are concerned with the nature of offending from the standpoint of relative seriousness (including frequency) or type of crime across an extended period of time (Piquero et al. 2003). In the current discussion, “frequency” of offending is concerned with individual levels of criminal activity during a given timeframe. Knowledge of the frequency of offending has important implications for the potential costs associated with an individual’s pattern of behavior. It has been at the heart of discussion of criminal careers because it is useful theoretically, and practically, to identify and explain those who offend at high rates as they tend to commit a large proportion of crime from an aggregate perspective as well (Piquero et al. 2007). For example, in their study of almost 10,000 adolescent males in Philadelphia, Wolfgang and colleagues (1972) concluded that 627 of the boys committed a majority of the total crimes. Figure 1 shows a career pattern for an individual case drawn from data on California Youth Authority parolees (see Sullivan et al. 2009) comprised of years with relatively high and relatively low offending frequency values. This pattern would be that of an offender with a fairly high frequency who offends across a significant part of the life course. Given this individual’s overall frequency of offending across the career, he might qualify as one of the minority of individuals who commit the majority of offenses identified in the Wolfgang study.

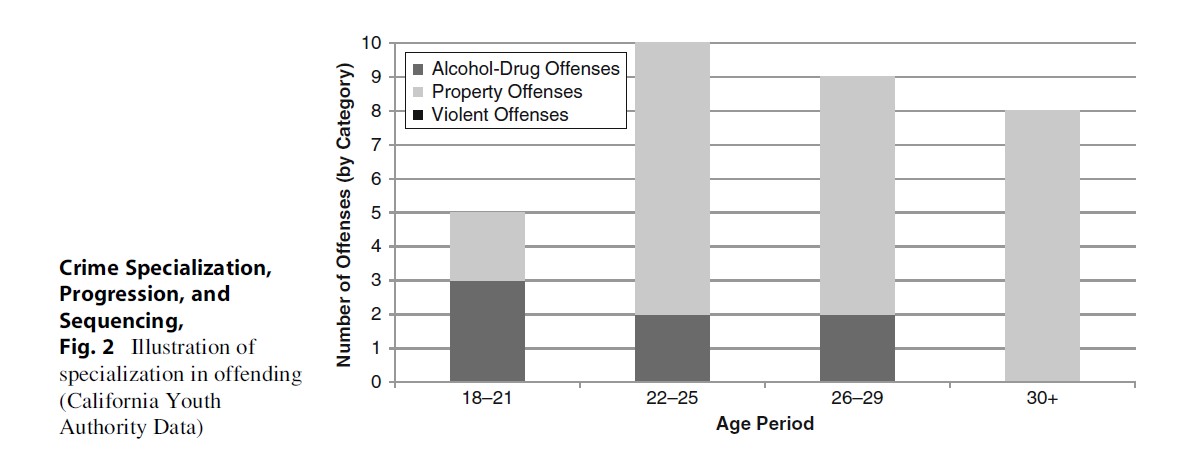

Offending specialization is primarily concerned with the nature of the crimes committed by individual offenders and the degree to which they form patterns across a career (or a portion of a career). To Osgood and Schreck (2007), specialization reflects systematic differences in the type of offenses committed by individuals. Systematic differences are those that are sizeable enough to distinguish one offender from another statistically. In most cases, specialization reflects some discernable pattern in form or type of offending across a defined period of time. Figure 2 offers a general sense of the contrast between specialization and versatility in offending. Over four time periods, this individual engages in no violent offenses and, although he starts with a mix of property and substance use offenses, is predominantly a property offender.

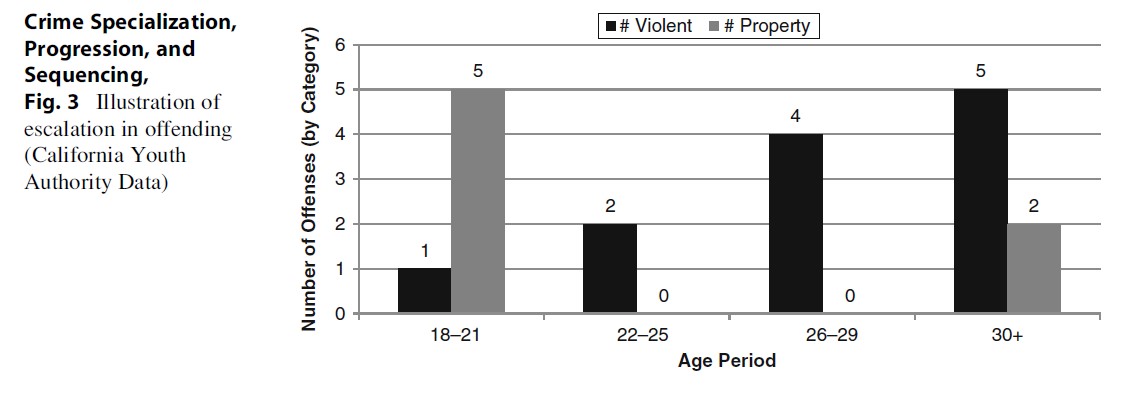

The issue of “progression” in criminal activity also reflects the presence of offending patterns but generally considers the nature of the acts in terms of seriousness as opposed to just type. The ideas of “escalation” and “de-escalation” in the seriousness of offending fall into this general framework (Blumstein et al. 1986; Piquero et al. 2003). Although escalation can be framed in terms of the increased frequency of offending, it is more generally be defined as a tendency to commit more serious offenses as the criminal career unfolds (Piquero et al. 2003). The idea of escalation/de-escalation inherently asks the question of whether an individual’s criminal behavior is getting “better” or “worse.” If one assumes that violent offenses are more serious than property offenses, the notion of escalation can be observed in Fig. 3 by contrasting the relative prevalence of the two offense types over time. Initially, this individual is involved in far more property crimes, but these wane over the observed time period, while violent crimes increase over time.

State Of The Art And Controversies

Frequency In Offending Careers

Measuring and making sense of the frequency of offending from a criminal careers perspective would appear to be a straightforward endeavor. Still, there are different ways of framing questions regarding the frequency of criminal behavior. One of the earliest controversies in research on criminal careers hinged around the distinction between total observed crime and individual frequency of offending (Blumstein et al. 1988; Gottfredson and Hirschi 1986). A society’s aggregated age-crime curve is necessarily composed of a number of different individual events. Sometimes these represent actions of individuals who are involved for the first and only time, but, more often, they represent repeated acts by the same individuals (see discussion of Wolfgang study above). The objective of criminal career research rests partly in distinguishing the latter group from the former.

The number of offenses per year for inactive offender has been given a label of Lambda (l) by some scholars (Piquero et al. 2007), and a great deal of the thinking and research in the study of criminal careers has focused on identifying and explaining the behavior of those high rate offenders. Because offending frequency research is concerned with active offenders, researchers employing the criminal career paradigm do not rely on aggregate crime rates. Per capita crime rates are calculated by dividing the total number of crimes committed in a specified area by the total population for the area. As such, they do not distinguish between those who commit crime (active offenders) and those who do not. Instead, frequency research relies on identifying and understanding Lambda.

Gottfredson and Hirschi (1990) argued that a single latent construct, criminal propensity, was the main influence on all aspects of the criminal career, including frequency. According to this view, the frequency of offending increases as criminal propensity becomes more elevated. Contrary to Gottfredson and Hirschi’s argument, however, early criminal career proponents posited that different factors influenced each of the dimensions, specifically that different factors influenced participation and, among active offenders, frequency (Smith et al. 1991). As such, they called for research to determine whether different variables were correlated with the separate dimensions of the criminal career and, if so, which of those affected each dimension. Smith and colleagues (1991) attempted to determine whether the factors associated with participating in crime and delinquency were different from those associated with the offending frequency of active offenders. The results were inconclusive, indicating that most of the correlates of frequency were also correlates of participation. There were, however, a few variables associated with one dimension and not the other. For example, age was associated with participation but not with frequency. Overall, the authors concluded that their data did not support the argument that a general propensity toward crime explained each of the dimensions of the criminal career.

Lambda values vary significantly among individual offenders and are skewed to the right (Blumstein et al. 1986). In other words, the majority of offenders commit relatively few crimes each year, while a small portion of offenders commit crime on a more frequent basis. For example, using a representative sample of prison and jail inmates in California, Michigan, and Texas, (Chaiken and Chaiken 1982) found that among offenders who committed at least one burglary prior to their incarceration, the median Lambda value was relatively small at 5.5 burglaries per year, whereas offenders in the 90th percentile committed over 230 burglaries per year.

Research has found a few factors that are consistently correlated with increased frequency rates, including early age of onset, frequent drug use (Rhodes 1989), unemployment, and previous high levels of criminal involvement (Blumstein et al. 1986). However, research on the relationship between frequency and certain demographic variables – age, sex, and race – is mixed. In their report, Blumstein et al. (1986) concluded that these variables were highly correlated with an individual’s participation in criminal activities but only marginally associated with individual frequency. For example, although an offender’s sex is typically a strong predictor of participation in criminal activity (Liu et al. 2011), research has shown that the offending frequencies of active females are not significantly different from those of active males (Blumstein et al. 1986; Rhodes 1989). Like Blumstein and colleagues, Rhodes (1989) reported that active male and female offenders had almost identical offending frequencies. Regarding race, Blumstein et al. (1986) concluded that among active offenders, the frequency rates of black and white offenders were nearly identical. However, contrary to the conclusions from Blumstein and colleagues, Rhodes (1989) found that nonwhite offenders had significantly higher Lambda values than whites.

The relationship between age and the frequency of offending has been heavily debated; in part, these discussions hinge on disentangling individual offending from aggregate patterns. Gottfredson and Hirschi (1986); Blumstein et al. (1988a, b) took differing perspectives in that the overall pattern observed in the age-crime curve might arise out of different processes, each with its own etiology and distinct implications for theory and practice. Gottfredson and Hirschi (1986) attributed the decline in the aggregate age-crime curve that occurs after its peak in late adolescence to decreased individual offending frequencies or individuals “maturing out of crime.” Proponents of the criminal career paradigm, however, argue that the causes of the decline are more extensive than simply maturing out of crime (Smith et al. 1991). They posit that the decline in aggregate crime rates may be influenced by both the number of offenders participating in crime and individual frequency rates. During early adulthood, many individuals terminate their criminal careers, while those that remain active commit crime at the same or elevated frequency. After reexamining the Glueck data, Blumstein et al. (1988a, b) found that annual arrest frequencies remained stable – ranging from 0.86 to 1.14 – for a sample of boys followed from ages 14 to 29.

The idea of career criminals, or offenders who commit relatively frequent crimes over an extended time period, is important to policymakers. The belief is that if these career criminals can be identified, policies aimed at preventing, controlling, or curtailing their careers – either through incarceration or other programs designed to prevent offending or recidivism – may produce a sizeable decrease in crime rates. One such policy that has been suggested (and incorporated in many jurisdictions) is selective incapacitation, which aims to identify and incarcerate serious career criminals in order to prevent the potentially significant number of crimes they would commit if free in the community (Gottfredson and Hirschi 1986). An example of selective incapacitation is habitual offender laws, or “three strikes” laws, in which repeat offenders are given a significantly longer sentence after their third felony conviction. In the original criminal careers report and other earlier works, Blumstein and colleagues (1986, 1988a, b) argued that additional research was needed to identify the legal variables correlated with high values of Lambda in order to rigorously consider and guide selective incapacitation policies.

Another possible approach is to use some of the identified correlates of high frequency of offending to identify targets for prevention efforts. For example, early age of onset is a noted marker of frequent offending, meaning that targeting resources toward adolescents who have early contact with the justice system may be one avenue by which later crime might be prevented (Ayers et al. 1999; Liu et al. 2011). Additionally, research typically finds that violent offenders have higher Lambda values than their nonviolent counterparts (Piquero 2000). As such, Piquero argued that prevention programs aimed specifically at reducing violent crimes might not be necessary. Instead, general prevention programs aimed at reducing offending frequency would concomitantly reduce violent crime as well since offenders with high frequencies tend to commit violent crime at a disproportionate level.

Although frequency research has become prominent since the original criminal careers report, there is still debate on which subset of offenders should be used in studying offender frequency. Studies typically draw their samples from one of two populations: current inmates or arrestees (Blumstein et al. 1986; Miles and Ludwig 2007). Inmate studies typically use retrospective interviews to determine the number and type(s) of crimes that inmates committed during a specified time period. Conversely, studies that sample arrestees (whether incarcerated or not) use official arrest reports to determine the number and type(s) of crimes for which an offender was arrested. Because frequency in the criminal career paradigm measures the number of crimes committed per year as opposed to the number of arrests per year, some researchers have argued that the most accurate way to estimate Lambda is by using retrospective inmate interviews where the inmates can describe crimes for which they were never arrested.

Both methods used to measure frequency rates have flaws. Self-reports suffer from problems with offenders accurately recalling past criminal acts and under-or overrepresentation of the number and type of crimes committed. However, the most serious potential problem with self-reports is selection bias. There may be a significant difference between offenders willing to share their criminal history and those unwilling to reveal their past criminal activities. In addition, self-report data on offense history is almost exclusively collected from incarcerated offenders. This poses problems when trying to generalize results to the entire offender population, most of whom never serve time in prison (Rhodes 1989).

Similarly, frequency values obtained from official arrest data may be biased due to the fact that arrests occur only for a small percentage of the number of crimes committed and/or the reality that part of an offender’s career may be spent in prison or jail. As such, the possibility of underestimating Lambda is a potential problem in using arrest data. One way to ensure more precise estimation of frequency rates is to combine the two methods by using arrest data to serve as a check on the accuracy of inmates’ self-reported criminal activities. Miles and Ludwig (2007) suggest that measuring Lambda is fraught with problems and, consequently, is of limited use in considering crime prevention policy.

As discussed above, offending frequency research has led to discussion of controversial selective incapacitation policies. These policies may be difficult to implement in practice; however. Some have argued that by the time these high-rate offenders are identified and trigger habitual offender laws, they may have done considerable damage but be on the downside of their criminal careers (Gottfredson and Hirschi 1990; Miles and Ludwig 2007). Limitations in empirical research and the very real possibility of false positives (i.e., predicting an offender will be a high-rate offender in the future and s/he does not) ensure that the controversy surrounding selective incapacitation laws will remain.

Specialization/Versatility In Offending Careers

Although typological and taxonomic identification of offender groups has long been a subject of criminological research and justice practice, this aspect of offending careers has also grown as a topic of interest since the 1986 “Criminal Careers” report. The degree to which offenders specialize or generalize in turn has implications for understanding the etiology of criminal offending in terms of explaining and responding to crime. The main interest from a criminal career perspective is whether, and to what degree, criminals concentrate their offending in particular offense types. In other words, do certain offenders engage predominantly, or exclusively, in drug offenses, sex offenses, violent offenses, or property offenses? If the answer to this question is yes, offenders might be placed in distinct groups based on their focus on certain crime types. If not, it may be futile, or even counterproductive, to develop strategies targeting particular subgroups of offenders based on the types of crimes in which they are presumed to solely or predominantly engage (e.g., sex offender treatment, drug offender treatment). In other words, absent specialization, criminologists should focus primarily on general explanations of crime, such as Gottfredson and Hirschi’s (1990) self-control theory, and it would be best if the system treated all offenders similarly no matter their instant offense – contingent on their frequency of offending. Conversely, the presence of specialization might suggest the use of more fine-grained explanations of offending that recognize the potential for qualitatively distinct groups of offenders. Policy-makers and practitioners might then look to make use of such grouping information in developing sentencing and treatment strategies.

Broadly speaking, two types of theories make implicit or explicit assumptions about the possibility of specialization. In contemporary criminology, general theories that make few distinctions between offenders in terms of the nature of their offending and the explanations derived from these theories typically suggest that offenders do not discriminate in the types of crimes that they commit. The General Theory of Crime suggests that offending is only one of a number of actions that might be undertaken in pursuit of short-term benefits at the expense of potential long-term consequences (Gottfredson and Hirschi 1990). Offenders are believed to have low levels of self-control which leads them to engage in a variety of criminal offenses without much regard for the form that they take. Consequently, there should be no recurring patterns of particular offense types. Offenders are unlikely to show specialization as this short-term, pleasure-seeking orientation will manifest itself differently depending on the situation (Britt 1994).

Conversely, taxonomic perspectives of criminal careers are open to the possibility that some distinctions among offenders exist – including those related to the types of crime committed. The criminal career paradigm defined by Blumstein and colleagues (1986) focuses on individual-level variation in offending across the life course. It also suggests that characteristics like specialization are worthy of theoretical explanation. This view holds that there are certain groups of offenders who warrant distinct explanations and may possibly require specialized treatment or intervention. For example, there may be a small group of serious, generalized offenders who engage in a continuous and varied track of antisocial behavior over time. At the same time, it is possible that certain individuals will engage in less serious forms of delinquency within the boundaries of adolescence before desisting around the time that they reach adulthood. This is the premise of Moffitt’s (1993) taxonomy of antisocial behavior, which is an example of a theory that outlines subgroups of offenders that are distinct in terms of the nature and etiology of their offending. Moffitt’s adolescent-limited offenders may specialize in relatively less serious antisocial behavior (e.g., status offenses, substance use), while life-course persistent offenders engage in a variety of offense types across a longer portion of their lives. The notion of offender types, however, has been criticized by those who espouse general views of crime and criminals. Even the use of the term “career,” which implies some coherent pattern of behavior over time, has been the subject of questions in this regard (Gibbons 1988).

Probably the biggest controversy in this area is whether those interested in understanding criminal behavior should bother to study specialization at all. Gibbons (1988) suggests that the typological schemes offered by both criminologists and criminal justice practitioners tend to fall short when tested against empirical data and, in general, the literature on this characteristic of the criminal career tends to show only modest levels of offender specialization (Piquero et al. 2003). Nevertheless, the fact that some important theoretical propositions in criminology have differing views on specialization, coupled with the reality that offenders are often grouped by type in policy initiatives and treatment programs, has led to continued empirical research.

Some early research in this area found that information about the nature of an offender’s previous criminal behavior was not a good predictor of later offense types (Wolfgang et al. 1972). Farrington and colleagues (1988) assessed the potential for specialization in a sample of juvenile court records and found an average coefficient value of 0.10, which falls well short of the 1.0 that would be expected if there was complete specialization in measured offending. They also compared the observed number of specialized offenders to what might be found by chance alone; roughly 20 % of their cases were characterized as specialists in that analysis. Blumstein et al. (1988a, b) found slightly higher levels of specialization in adult offenders, but these individuals represented just a minority of the population. Identifying limitations in the previous approaches, Britt (1996) found that offenders showed a much greater tendency to repeat the same offense than switch to another on their subsequent criminal act. Mazerolle et al. (2000) analyzed diversity index values, which were first used to account for similarity/dissimilarity among species, to assess specialization and found that their sample exhibited fairly diverse offending profiles. Later work with data from the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development likewise identified little evidence of violent specialization (Piquero et al. 2007).

Despite these findings, some recent research suggests that answering questions about the degree of specialization in offending may require a slightly more nuanced view. In his ethnographic research, Shover (1996) found that, although it may be obscured by the variety that is apparent across an entire criminal career, offenders seem to make short-term changes in their offending indicative of specialized behavior. Francis et al. (2004) also identified some offender “types” in their study of career-length crime patterns. Osgood and Schreck (2007) report consistent evidence of specialization in violent offending using general population data on self-reported delinquency. Like Shover (1996), these studies suggest that offenders may alter their preferences over time, which adds up to a conclusion of versatility when looked at across a lengthy career but also suggests that it might be useful to consider these short-term, specialized patterns in more depth.

While these findings suggest some degree of specialization in offending, it is important that they are viewed in light of the larger body of research that has found that offenders tend to commit a variety of different criminal acts over their careers. Britt (1994) points out that even those studies that identify specialized offenders suggest that they comprise only a small portion of the overall population. Over time, research on specialization has drawn on a variety of methods, and, in some cases, it appears that the observed differences in results may be partly attributable to alternative approaches to measurement or analysis (Sullivan et al. 2009). Some studies that have identified support for the notion of specialization (e.g., Francis et al. 2004; Osgood and Schreck 2007) have used measurement and analytic techniques that may provide a better test for the presence and nature of specialization than those used previously. Also, more recent research on specialization has begun to better incorporate theory which helps in moving past the blunt question of whether there is any specialization while also illustrating the potential utility of understanding this aspect of criminal careers. For example, a recent study considered the question of specialization within the context of family violence using clear theoretical and preventive foundations (Piquero et al. 2006). Synthesizing the results of empirical studies, it is clear that most offenders will commit a variety of different types of crime over their careers, but there may be parts of the career where they tend to engage in one type or another and those patterns should be considered in theoretical development around criminal careers (Armstrong and Britt 2004).

Progression And Sequencing In Criminal Careers

Research on progression and sequencing in criminal careers is also concerned with identifying and explaining patterns across criminal careers (Piquero et al. 2003). While the question of how careers progress or sequences unfold can relate to specialization, it is primarily concerned with the possibility that there are trends in seriousness across the career. Although implicit in a number of approaches to dealing with offending behavior (e.g., diversion programs that seek to intervene with less serious offenders to prevent more serious offenses later on), few perspectives have formalized the notion of escalation in offending theoretically. Loeber and Hay (1997) offered a pathways model that did consider the possibility of escalation to violent behavior after a period of time engaging in less serious forms of delinquency. Their expectation is consistent with the idea of heterotypic continuity where less serious forms of aggression are believed to later give way to more serious violent behavior at a later stage of development. This theory also laid out several precursors to later escalation in aggression (e.g., temperament, cognitive factors). There are also some notions regarding escalation in certain subtypes of offenders. For example, sex offenders and men who engage in domestic violence are perceived to be at risk of escalation in the nature or frequency of their behavior over time.

Of the three criminal career dimensions considered in this research paper, progression has received the least amount of attention (Armstrong and Britt 2004; Liu et al. 2011). Piquero et al. (2003) reviewed the evidence on the potential for escalation in offending and found the results to be decidedly mixed. Any observed patterns appear to be age-graded in that the seriousness of offending often trends upward for juveniles. Farrington (2003) asserted that most juveniles begin their criminal career by committing relatively minor offenses but tend to commit progressively more serious offenses until the age of 20. Conversely, the typical progression of offense seriousness for adult offenders appears to be stable or declining over time (Farrington 2003; Piquero et al. 2003).

Britt (1996) offered a new modeling strategy for identifying and testing specialization and escalation, conducting a series of analyses that were similar to those previously used to understand social mobility. Using data from a sample of Michigan offenders and a crime-specific breakdown, he identified statistical trends showing general support for a pattern of greater seriousness in offense type from one to the next. A somewhat similar recent study by Massoglia (2006) sought to understand offending patterns in the transition from adolescence to adulthood. Although this study only covered a portion of possible criminal careers, it provides insight into patterns of escalation and de-escalation. Massoglia identified groups that represented clear instances of escalation. Specifically, three subgroups of individuals in that study (26 %) had transition patterns that fit with notions of escalation (i.e., moved to a more serious offending class). This included cases that moved from normative deviance (e.g., truancy, disorderly conduct) to a predatory offending or illicit drug use class in early adulthood. Piquero and colleagues (2006) studied the question of escalation within the framework of spousal assault using data from victim interviews. This analysis focused on the severity of injury experienced by the victim in a second assault. They identified a high probability of escalation in these successive incidents of domestic violence in one site, suggesting that this pattern is prevalent. In other sites, there was a mix of escalation and de-escalation in the injuries experienced by victims. In general, this contradicted the notion that escalation is endemic to that particular form of criminal behavior.

Policy and practice around escalation are primarily focused on the fact that, if there is a progression from less to more serious offending, the earlier behavior can be used as a marker for intervention and the more serious and harmful behavior on the part of that individual may be prevented. For example, using conviction data from the England and Wales Offenders Index, Liu et al. (2011) examined the seriousness of offenses committed by over 4,000 offenders to determine whether escalation and/or de-escalation of offense seriousness is present over the criminal career. They concluded that offenders with few convictions (1–5) showed de-escalation over time, whereas offenders with more than five convictions tended to escalate in offense seriousness. As such, the authors argued that intervention policies should be aimed at persistent offenders because they are more likely to eventually escalate into committing serious, violent crimes, a view that is shared by other researchers (Ayers et al. 1999).

Conclusions And Future Research

In general, criminologists now know considerably more about the criminal career than was known 25 years ago when research and discussion in this area really began to take off. At that point, the idea of a criminal career was one that made sense intuitively, and Blumstein and colleagues (1986) summarized a good deal of research to that point that supported the usefulness of the perspective. Still, at that time, there were questions in terms of its fundamental connection to observed data and its potential implications for a general understanding of crime and related policy and practice. For example, there are those that asserted that longitudinal research of the type described above was too expensive and time-consuming and would prove to be of limited use to theory and practice (Gottfredson and Hirschi 1986).

There are, however, some important conclusions that can be reached upon reflection a couple of decades later. It is clear that most crime is committed by a small pool of high-frequency offenders and a number of correlates of those high-frequency careers have been identified (e.g., early age of onset, career length, and frequent drug use). In terms of specialization, it is safe to say that most serious offenders will engage in a variety of different crime types over the course of a lengthy criminal career, but it would be an overstatement to say that there is no group of specialized offenders – particularly when disaggregating patterns of behavior that can extend years or decades. Similarly, the research on progression in offending that includes a pattern of escalation is fairly mixed. Some evidence has been found to support the idea of escalation, but it seems to be contingent on the context of the study.

So it is the case that criminologists currently know more about the three dimensions of the criminal career considered here. At the same time, there appears to be some limitations in knowledge as well as some question around the utility of pursuing these research questions given the methodological challenges inherent in their study. For example, although prevention may be more desirable than longer-term incapacitation as a method of dealing with high-frequency offenders, the question of early identification continues to loom large. Resolving the question of false positives and false negatives is a difficult one as predicting behavior is a challenging endeavor – even with high-quality information on risk factors. Consequently, the identification and response to high Lambda offenders continues to be a difficult empirical and practical question. Additionally, while advances in measurement and analytic techniques have helped in considering the question of offender specialization and progression more thoroughly, efforts to consider patterns in criminal offending in a clearer theoretical framework are also emerging with increasing regularity. It will be important in the future to determine whether the identification of a small group of specialists and those with clear patterns of offending escalation have important implications for theory, policy, and practice or are mainly just products of intuitively appealing notions about the nature of criminal behavior. This will be more helpful in terms of understanding criminal careers than a simple “yes/no” answer to the question of whether specialization or escalation in offending exist. In general, the next iteration of research on these topics should continue to explicitly embed an understanding of the dimensions of the active criminal career in the pursuit of knowledge about the processes by which criminal behavior is sustained over time while also attending to any implications for practice that might emerge.

Bibliography:

- Armstrong TA, Brit CL (2004) The effect of offender characteristics on offense specialization and escalation. Justice Q 21(4):843–876

- Ayers CD, Williams JH, Hawkins JD, Peterson PL, Catalano RF, Abbott RD (1999) Assessing correlates of onset escalation de-escalation and desistence of delinquent behavior. J Quant Criminol 15(3):277–306

- Blumstein A, Cohen J, Roth JA, Visher CA (eds) (1986) Criminal careers and “career criminals”. National Academy Press, Washington, DC

- Blumstein A, Cohen J, Das S, Moitra SD (1988a) Specialization and seriousness during adult criminal careers. J Quant Criminol 4:303–345

- Blumstein A, Cohen J, Farrington DP (1988b) Criminal career research: its value for criminology. Criminology 26(1):1–35

- Britt CL (1994) Versatility. In: Hirschi T, Gottfredson M (eds) The generality of deviance. Transaction, New Brunswick

- Britt CL (1996) The measurement of specialization and escalation in the criminal career: an alternative modeling strategy. J Quant Criminol 12:193–207

- Chaiken JM, Chaiken M (1982) Varieties of criminal behavior. Rand Corporation, Santa Monica Farrington DP (2003) Developmental and life-course criminology: key theoretical and empirical issues— the 2002 Sutherland award address. Criminology 41(2):221–255

- Farrington DP, Snyder H, Finnegan T (1988) Specialization in juvenile court careers. Criminology 26:461–485

- Francis B, Soothill K, Fligelstone R (2004) Identifying patterns and pathways of offending behaviour: a new approach to typologies of crime. Eur J Criminol 1:47–87

- Gibbons DC (1988) Some critical comments on criminal types and criminal careers. Crim Just Behav 15(1):8–23

- Gottfredson M, Hirschi T (1986) The true value of lambda would appear to be zero: an essay on career criminals, criminal careers selective incapacitation cohort studies and related topics. Criminology 24(2):213–234

- Gottfredson M, Hirschi T (1990) The general theory of crime. Stanford University Press, Palo Alto

- Liu J, Francis B, Soothill K (2011) A longitudinal study of escalation in crime seriousness. J Quant Criminol 27(2):175–196

- Loeber R, Hay D (1997) Key issues in the development of aggression and violence from childhood to early adulthood. Annu Rev Psychol 48:371–410

- Massoglia M (2006) Desistance or displacement? The changing patterns of criminal offending from adolescence to adulthood. J Quant Criminol 22:215–239

- Mazerolle P, Brame R, Paternoster R, Piquero A, Dean C (2000) Onset age persistence and offending versatility: comparisons across gender. Criminology 38:1143–1172

- Miles TJ, Ludwig J (2007) The silence of the lambdas: deterring incapacitation research. J Quant Criminol 23:287–301

- Moffitt TE (1993) Adolescent-limited and life-course persistent antisocial behavior: a developmental taxonomy. Psychol Rev 100:674–701

- Osgood DW, Schreck CJ (2007) A new method for studying the extent stability and predictors of individual specialization in violence. Criminology 45:273–312

- Piquero AR (2000) Frequency specialization and violence in offending careers. J Res Crime Delinq 37(4):392–418

- Piquero AR, Farrington DP, Blumstein A (2003) The criminal career paradigm. In: Tonry M (ed) Crime and justice: a review of research, vol 30. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Piquero AR, Brame R, Fagan J, Moffitt TE (2006) Assessing the offending activity of criminal domestic violence suspects: offense specialization escalation and de-escalation evidence from the spouse assault replication program. Public Health Rep 121:409–418

- Piquero AR, Farrington DP, Blumstein A (2007) Key issues in criminal career research: new analysis of the Cambridge study in delinquent development. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

- Rhodes W (1989) The criminal career: estimates of the duration and frequency of crime commission. J Quant Criminol 5(1):3–32

- Shover N (1996) Great pretenders: pursuits and careers of persistent thieves. Westview, Boulder

- Smith DA, Visher CA, Jarjoura GR, O’Leary V (1991) Dimensions of delinquency: exploring the correlates of participation frequency and persistence of delinquent behavior. J Res Crime Delinq 28(1):6–32

- Sullivan CJ, McGloin JM, Ray JV, Caudy MS (2009) Detecting specialization in offending: comparing analytic approaches. J Quant Criminol 25:419–441

- Wolfgang M, Figlio R, Sellin T (1972) Delinquency in a birth cohort. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.