This sample Crimes of The Powerful Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Crimes of the powerful have occurred throughout humanity’s existence, from the ancient armies and Roman leadership to the aristocratic criminal of the eighteenth Century to the modern corporate CEO and head of state. While these behaviors did not come under the scrutiny of criminologists until the last century, there is a growing body of critical theoretical frames that have been used to explain the etiological factors associated with crimes of the powerful.

Fundamentals

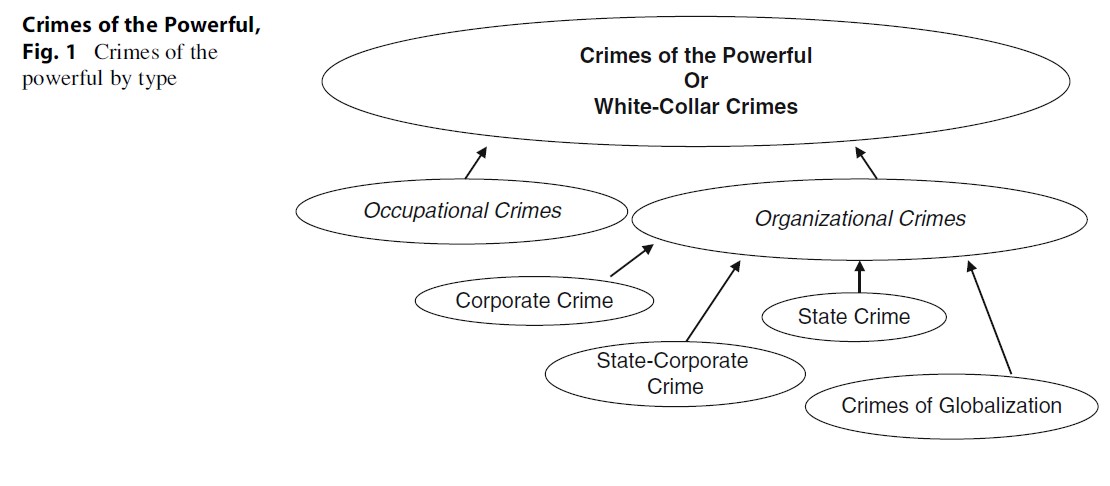

Theoretical explanations of the crimes of the powerful are not straightforward or universally applicable. As such, it helps to first understand the typical forms by which these types of criminality are generally categorized as well as the levels of analysis with which theories can be applied. Crimes of the powerful, also referred to as white-collar crimes, can be broken down into two main categories: occupational and organizational crimes. Occupational crimes are those committed by individuals within the context of their occupation for their own self-interests whereas organizational crimes are those committed by individuals within the context of their occupation for the interests of or benefit of the organization. The latter does not imply that the individual may not benefit as well, however, a major component of organizational crime is the inclusion of organizational benefit (Fig. 1).

Organizational crimes can be broken down into four major subtypes: (1) state crime, (2) corporate crime, (3) state-corporate crime, and (4) crimes of globalization.

State crimes are illegal or socially injurious act of omission or commission by an individual or group of individuals in an institution of legitimate governance which is executed for the consummation of the operative goals of that institution of governance (Kauzlarich and Kramer 1998). Genocide, human rights violations, war crimes, illegal war, and crimes against humanity are actions that fall under the category of state crime. State crimes are historically and contemporarily ubiquitous and result in more injury and death than traditional street crimes such as robbery, theft, and assault. Consider that genocide during the twentieth century in Germany, Rwanda, Darfur, Albania, Turkey, Ukraine, Cambodia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and other regions claimed the lives of tens of millions and rendered many more homeless, imprisoned, and psychologically and physically damaged (Rothe and Kauzlarich 2010).

Corporate crimes are committed on behalf of business interests, sometimes by individuals, sometimes by groups; they surface among the self-employed and among executives of companies large and small. Corporate crime may include theft, fraud, and violence. Famous cases of financial fraud include those committed by Enron and Adelphia in which the manipulation of stocks and various forms of deceptive accounting resulted in the theft of billions of dollars from investors. Violations of worker safety and environmental regulations are also major forms of corporate crime.

State-corporate crimes are illegal or socially injurious actions that result from mutually reinforcing interaction between institutions of political governance and institutions of economic production and distribution (Kramer and Michalowski 1991: 5); also see Michalowski and Kramer (Michalowski and Kramer 2006) and Matthews and Kauzlarich (2000).

The concept of state-corporate crime has been used to examine the space shuttle Challenger explosion (Kramer 1992; Michalowski and Kramer (2006), the environmental devastation caused by US nuclear weapons production (Kauzlarich and Kramer 1998; Michalowski and Kramer (2006), and the deadly fire at the Imperial Food Products chicken processing plant in Hamlet, North Carolina (Aulette and Michalowski 1993; Michalowski and Kramer (2006). Other examples of state-corporate crime include the I.G. Farben Company’s involvement with Nazi atrocities (Michalowski and Kramer (2006), the Wedtech case involving defense contractor fraud (Friedrichs 1996), and the violent and deadly crash of ValuJet flight 592 in May of 1996 (Matthews and Kauzlarich 2000).

Crimes of globalization are activities that lead to a range of physical and economic injury committed by international agencies in the interest of facilitating global capitalism (Friedrichs and Friedrichs 2002). Most criminological literature has examined the harms resulting from the World Bank’s funding of capitalist expansion into less developed countries, which results in the marginalization of indigenous peoples, higher rates of income inequality, environmental disaster, health crises, and political corruption (Ezeonu and Koku, Ezeonu and Koku 2008; Rothe 2010; Rothe et al. 2006; Rothe et al. 2009). Although most of the harms are not directly criminalized by political authorities as in the case of most traditional forms of corporate crime, expanded definitions of crime rooted in critical criminology are used to frame the activities as subject to criminological examination.

Occupational crimes are committed against an employer are also understood by most critical criminologists as the outcome of the need for and fetish with money in capitalist societies. While not profit-seeking in the same way as organizations, both traditional street crime and occupational white-collar crime stem from economic factors, whether real or perceived.

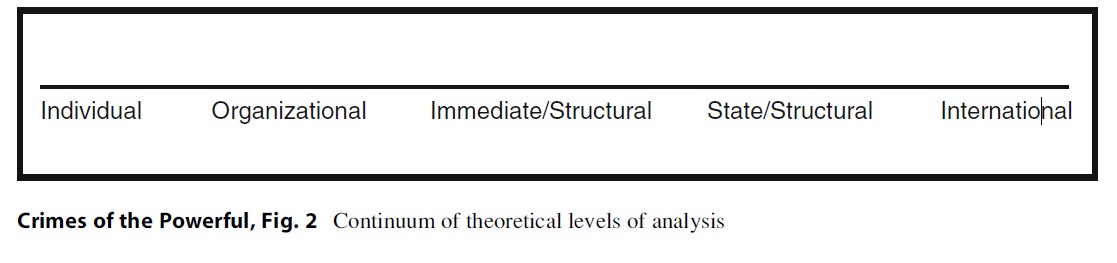

This distinction between the various forms of crimes of the powerful reviewed above is important for any discussion or application of theory. For example, a theory explaining the motivation of someone stealing 500.00 dollars from their employer for their own financial gain is unlikely to involve the same situational and motivational factors of a head of state committing genocide. Nor are the opportunity structures or controls going to be the same. Likewise, theories apply to different levels of analysis. Each of these can be thought of as operating along a continuum from the individual or interactional level of analysis to the supra-macro level or international level (Fig. 2).

The distinction between these various levels of analysis is relevant to the type of crimes being analyzed as well as the theoretical model that can be applied. For example, a theoretical approach that explains individual level behavior may have limited explanatory power in the case of corporate crime, in which organizational culture or pressures facilitating or “causing” motivating forces. As such, theories that explain occupational crimes for example differ from those that attempt to explain organizational crimes such as corporate, state-corporate, state crime or crimes of globalization.

Critical Theories

Given the range of theories that have been applied to the crimes of the powerful over the last century, it is impossible to review each approach. The emphasis here is on critical and integrated theories of crime, although their relationships to non-critical explanations will be briefly noted. What distinguishes critical theories of crime from other explanations is their opposition to – not just interest in – unequal fundamental political, economic, and social structures and relationships. The major forms of critical theories include Marxist, left realism, feminist, postmodernism, cultural, and peacemaking perspectives. Respectively, their critiques are centered on capitalism, stratification and inequality, patriarchy, modernity, positivist criminology, and war-making. Critical theories of crime have roots in general sociological conflict theory, and those that focus on crimes of the powerful are almost exclusively inspired by Marxist sociological theory (now often referred to as political economy theory).

While Karl Marx said little about crime, some criminologists, especially critical criminologists, recognize a substantial debt to this nineteenth century scholar. Marx believed that a society’s mode of economic production directly influenced the manner in which relations of production are organized and thus determines in large part the organization of social relations, the structure of individual and group interaction. Under a capitalist mode of production, there are those who own the means of production and those who do not. The former group is known as the bourgeoisie and the latter as the proletariat. The bourgeoisie, or ruling class, controls the formulation and implementation of moral and legal norms, and even ideas. Both classes are bound in relationship to one another, but this relationship is asymmetrical and exploitive. This relationship affects law and crime in fundamental ways. Laws are created by the elite to protect their interests at the expense of the proletariat. Marxists might point out that even presumably simple and well supported laws may not work in the interests of the have-nots, though they may be perceived to be a representation of the collective will of a society.

Over a century ago an intellectual follower of Marx, Willem Bonger, applied some of Marx’s arguments to crime in capitalistic societies. In Criminality and Economic Conditions (published in English in 1916), Bonger observed that capitalistic societies appear to have considerably more crime than do other societies. Furthermore, while capitalism developed, crime rates increased steadily. Under capitalism, Bonger argued, the characteristic trait of humans is self interest (egoism). Given the emphasis on profit maximization and competition, and the fact that social relations are class structured and geared to economic exchange, capitalistic societies spawn intraclass and interclass conflicts as individuals seek to survive and prosper. Interclass conflict is one sided, however, since those who own and control the means of production are in a position to coerce and exploit their less fortunate neighbors. Criminal law, as one instrument of coercion, is used by the ruling class to protect its position and interests. Since social relations are geared to competition, profit seeking, and the exercise of power, altruism is subordinated to egoistic tendencies.

Applied to crimes of the powerful, Bonger’s argument, which is still a basic assumption of modern Marxists, is that those in positions of corporate power are almost always focused on making, sustaining, or increasing profit. Financial crimes by corporations are therefore seen as a logical extension of capitalist logic as are violations of worker and environmental regulations and laws. Quite simply, from a basic Marxist approach, corporate crime is caused by the overriding allegiance to profit no matter who might be hurt along the way. State and state-corporate crime can also be viewed from a Marxist perspective. Considering state-corporate crime, states are seen as primarily facilitators of capital accumulation for corporations. This is especially true in the case of state-facilitated state-corporate crime in which “governmental regulatory institutions fail to restrain deviant business activities, because of direct collusion between business and government, or because they adhere to shared goals whose attainment would be hampered by aggressive regulation” (Kramer and Michalowski 1991: 6). As Barnett (1981: 7) and Chambliss and Zatz (1993) have noted, a major goal of the US state has been to promote capital accumulation, and the state’s regulatory function “must not be so severe as to diminish substantially the contribution of large corporations to growth in output and employment.” For example, while state regulatory agencies have been created to help protect workers (Occupational Safety and Health Administration), the environment (Environmental Protection Agency), and consumers (Consumer Product Safety Commission), these agencies will not undermine an industry’s fundamental contributions to the functional requirements of the economy (Matthews and Kauzlarich 2000). In sum, while laws and regulations governing corporate behavior are plentiful, Marxist scholars will point out that the laws lack serious enforcement and associated penalties which therefore do little in the way of deterring corporations from crime. This is not a coincidence since capitalist states are more interested in protecting capital than they are the environment, workers, and consumers. It is important to note that most Marxist scholars now see the state as having some relative autonomy in that it is not always directly working with and for capitalists, but rather the long term survival and expansion of business and capital in general. As Chambliss and Zatz (993: 10) note “Should the state represent only the interests of capitalists, the conflicts will increase in intensity, with workers pitted against the state…. Were the state to side with the workers.. .the system would likewise collapse and a new social order would have to be constructed. Faced with this dilemma, officials of the state attempt to resolve the conflict by passing laws, some which represent the interests of capitalists and some the interests of workers.”

Similar logic is used by Marxist or political economy critical criminologists to explain the basic causal properties of crimes of globalization. In the Marxist view, states will favor business in policy making, regulatory agency mandates, and international activities. The latter is especially important in recent decades as the process of globalization spreads capital and culture throughout the far reaches of the globe. International agencies such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Trade Organization are clearly pro-capitalist, free market neoliberal agencies that see private ownership and corporate control, rather than socialist and democratic collectivist initiatives, as the main ways to link and grow economies. As such, many crimes of globalization are directly related to the economic interests of those in power rather than the welfare of indigenous populations.

The most recent, cutting-edge critical theories of crimes of the powerful have been developed under the umbrella of “crimes of empire.” Michalowski (2009: 308) defines this as “the construction of development strategies, citizenship, sovereignty and culture in subordinate spaces through agreements with local elites if possible, and by force if necessary, in order to facilitate processes of capital accumulation and distributions of power that are disproportionately beneficial to a dominant cosmopolitan center.” Examples of crimes of empire include many illegal military invasions, most forms of imperialism and colonialism, training and support for totalitarian regimes by capitalist states, and the suppression of human rights across the globe. Major recent analyses of crimes of empire have occurred in the context of the United States invasion of Iraq in 2003 (Kramer and Michalowski 2005). Many powerful states, like powerful corporations, are in a constant search for growth, which may include expanded territory, expedited avenues for capitalist accumulation, and increased social and cultural power and resources. The history of state crimes is replete with these interests, whether we are considering historical or more contemporary empire building by European, North American, Middle East, or African countries.

A constant thread in imperialism and “war for empire” is the use of military force not only against combatants but also civilians, which is a grave crime against humanity, and one that is often normalized in the context of patriotism or self-defense in communicative discourse (Kramer 2010). Very early on non-critical scholars of traditional street crime theorized about the manner in which deviance or crime can be neutralized (Sykes and Matza 1957). Modern critical scholars of state crime in particular have found that Sykes and Matza’s (1957) theory is very useful in understanding crimes of the powerful. Originally, Sykes and Matza (1957) proposed the concept of techniques of neutralization, which involves mental and social rationalizations both before and after crimes are committed. The key forms of neutralization and justification include (1) denial of responsibility, (2) denial of injury, (3) denial of victim, (4) condemnation of the condemner, and (5) appeal to higher authority. These techniques can best be understood in terms of the simple process of rationalizing one’s own behavior, whether in response to cognitive dissonance, as a precondition to acting, aiding a costbenefit analysis, or as a post-action to minimize or attempt to legitimize or neutralize the guilt of a person’s behaviors or after the fact accountability. While techniques of neutralization are often used to explain occupational crimes, this approach also aids in our understanding of specific individuals within organizations.

Scholars of state crime and crime of the powerful in general have found evidence of the operationality of techniques of neutralization (Cohen 2001; Kauzlarich et al. 2000; Kramer 2010; Simon 1999; Vaughn 1996). Indeed, one of the most important things which separate state victimizers from their victims is their power to exert their will. Most often, victimizers do not acknowledge the degree to which their policies have caused harm while assessing the effectiveness of their policies to bring about desired change or to maintain their position of dominance. Unjust and injurious domestic and international policies can also be downplayed by neutralizing reasonable categorical imperatives (e.g. do no harm) by employing bankrupt utilitarianism, which may or may not be guided by ethnocentric paternalism. Often times harms are neutralized by denying responsibility, dehumanizing the powerless for purposes of exploitation, and appealing to higher loyalties (i.e. the capitalist political economy and “national security”) (Kauzlarich et al. 2000; Simon 1999).

With respect to the criminal historical treatment of Native Americans within the United States, “colonists quickly justified their violence by demonizing their enemies” Takaki (1993: 43). However, the transference of one’s own negative tendencies to another group is not something new. While Native Americans were seen as unruly, “God-less” savages, Takaki (1993) notes that the atrocities committed by the civilized whites against the Native Americans, were, in fact savage. It is in this light, then, that Native Americans became an enemy worthy of indiscriminate killing. In much the same manner, the indiscriminate killing of the “God-less” communists of Central America during the US imperialist project there were also justified in a similar manner.

In sum, the most longstanding and powerful critical analysis of the crimes of the powerful in critical criminology hinges on the assumption that corporations pursue goals of profit and expanded market shares and along the way cause significant legal and illegal harm and injury. States do so as well, either for empire building or the facilitation of corporate capitalism. Some critical scholars have taken issue with this and suggest that not all crimes of the powerful can be delineated down to economic motivations as this ignores religious, political, ideological, and cultural factors. Further, classic Marxist theory ignores other levels of analysis as well as obvious factors such as social controls and opportunities for crime. This has led to the development of critical integrated theories of crime. While these models are designed to explain state crime, they are also applicable to many other forms of organizational crime.

Critical Integrated Theoretical Perspectives

The earliest attempts to generate a theoretical model of state crime date back to Ronald Kramer and Raymond Michalowski’s (1990) work on state-corporate crime (see Michalowski and Kramer 2006 for a complete history). The theory was later expanded on and clarified by several other criminologists and remains the only comprehensive integrated theory for addressing organizational crimes, particularly state crimes, to date. For example, in 1998, David Kauzlarich and Ronald Kramer provided a detailed schematic of their proposed integrated theoretical frame which incorporated anomie and political economy theories at the state/structural level, organizational theory at the meso level and strain, rational choice, differential association, and routine activities at the interactional level of analysis. Kauzlarich and Kramer discuss how motivation is affected by one’s socialization within that environment, the social meaning given to his or her behavior, an individual’s goals, and issues of personality such as personal morality and obedience to authority.

Borrowing from Sykes and Matza (1957), reviewed above, they include techniques of neutralization as a variable of control. At the organizational level, Kauzlarich and Kramer draw heavily from organizational theorists to include instrumental rationality, role specialization, and task segregation. At the structural or institutional level of analysis, the major social institutions and social structure are included, particularly the political and economic institutions and their interrelationship as well as anomic conditions. Kauzlarich and Kramer (1998: 146) suggest the primary assumption of that perspective is that the very structure of corporate capitalism provides the impetus toward organizational crime, thus becoming crimes of capital (Michalowski 1985). They further propose that the political economy perspective stresses the shaping and/or constraining influences of the broader historical structure of a society as a factor of organizational behavior. This includes factors such as the culture of competition, economic pressure, and performance emphasis.

While this integrated model has proved useful in examining numerous cases of organizational crime (see Michalowski and Kramer 2006), the theory has been critiqued for its heavy emphasis on the criminogenic nature of capitalist social organization, which limits the theory to those crimes associated primarily with the corporate culture or within the United States. Further, Dawn L. Rothe and Christopher Mullins have suggested that the theory fails to recognize several other key factors associated with crimes of the powerful, such as weakened and transitional states, the involvement of militias, ideological and religious motivating forces, and international relations. To strengthen and expand the explanatory power of Kauzlarich and Kramer’s (1998) theory, Rothe (2006, 2009) and Rothe and Mullins (2008, 2009) proposed an expanded version of the integrated model. This included expanding the levels of analysis to include the international to incorporate the increasingly international nature of organizational criminality (as recognized by global political economy theory) and by recognizing both formal controls and informal controls or constraints on organization as well as individuals.

Another difference between Kauzlarich and Kramer’s model and that of Rothe and Rothe and Mullins is the inclusion of an often ignored component of some forms of crimes of the powerful – social disorganization. While much attention has been paid to organizational context and decision-making processes by scholars of organizational crime, there is a similarly rich criminological tradition which examines how social forces work within communities that are disorganized to produce criminal actions and actors. Coming out of the Chicago School of thought, social disorganization theory (Bursik and Grasmick 1993; Shaw and McKay 1942) suggests that when communities possess a diminished capacity to create and enact informal mechanisms of social control, crime rates increase. The expanded integrated model incorporates this to provide an explanatory tool for a host of crimes of the powerful including those of heads of state operating in specific conditions as well as other organizations including corporate endeavors. Others have followed this avenue by examining social disorganization in relation to private military contractors’ (PMC) criminality in fields of operation (Rothe and Ross 2010). It has been noted that PMCs often operate within a disorganized environment. This not only includes the community level, but the state and organizational ones as well. After all, war-torn areas are by definition disorganized.

In sum, Rothe and Mullins use many of the theoretical concepts advanced by Kramer, Michalowski, and Kauzlarich, but expand the theory to incorporate international variables, factors that are not associated with capitalistic endeavors of corporations and states, and components of social disorganization. In addition, they propose other factors and theoretical concepts that allow for the adaptation of catalysts that may be unique to specific cases (e.g., paramilitary groups, insurgencies, militias, postcolonial conditions, and weakened or illegitimate governments).

Summary

Crimes of the powerful are complex. While there are numerous non-critical theories of crime (rational choice, routine activities theory, anomie theory, to name a few) that have been used to explain occupational and organizational crimes, the focus here has been on critical and integrated approaches. Critical theories focus on power, and in the study of white-collar crime, power is mostly considered to be synonymous with some form of capital accumulation or the practices designed to protect or expand economic resources.

Marxist or political economy theorists have been criticized for being too simple in causal logic. Surely the desire for profit or money is a strong motivation for behavior, yet not all corporations and states commit the same amount or type of crime. Moreover, it has been noted that ideological and religious motivations can be as strong as economical drives. Further, contexts for crime are important for they help explain under what particular situations crime is more or less likely to occur. This is where integrated theories have helped enrich the study of the causes of occupational and organization crime. Crime is multi-dimensional, even if it stems from the same source, and using theories that attend to all levels of analysis help us understand how organizations and people within them come to learn and practice harmful or injurious ways in the courses of their personal and professional lives.

Bibliography:

- Almond G (1990) A discipline divided: schools and sects in political science. Sage, Thousand Oaks

- Aulette JR, Michalowski RJ (1993) Fire in hamlet: a case study of state-corporate crime. In: Tunnell K (ed) Political crime in contemporary America. Garland, New York, pp 171–206

- Barak G (ed) (1998) Integrating criminologies. Ashgate/ Dartmouth, Aldershot

- Barnett H (1981) Corporate crime, corporate capitalism. Crime Delinquency 27(1):4–23

- Bonger W (1916) Criminality and economic conditions. Little, Brown, Boston

- Bonger W (1969) Criminality and economic conditions, abridged version. Indiana University Press, Bloomington

- Bursik RJ Jr, Grasmick HG (1993) Economic deprivation and neighborhood crime rates 1960–1980. Law Society Rev 27(2):276–280

- Chambliss W, Zatz M (1993) Making law: the state, the law, and structural contradictions. Indiana University Press, Bloomington

- Cohen S (2001) States of denial: knowing about atrocities and suffering. Polity Press, Cambridge

- Ezeonu I, Koku E (2008) Crimes of globalization: the feminization of HIV pandemic in Sub-Saharan Africa. The Global South, 2, 2, Africa in a Global Age, 112–129

- Friedrichs D (1996) Trusted criminals: white collar crime in contemporary society. Wadsworth, New York

- Friedrichs DO, Friedrichs J (2002) The World Bank and crimes of globalization: a case study. Soc Justice 29(1–2):1–12

- Green P, Ward T (2004) State crime: governments, violence and corruption. Pluto Press, London

- Kauzlarich D, Kramer R (1998) Crimes of the American nuclear state: at home and abroad. Northeastern University Press, Boston

- Kauzlarich D, Matthews R, Miller W (2000) Toward a victimology of state crime. Crit Criminol 10:173–194

- Kramer R (1982) Corporate crime: an organizational perspective. In: Wickman P, Daily T (eds) White collar and economic crime. Lexington Books, Lexington, pp 75–94

- Kramer RC (1992) The space shuttle challenger explosion: a case study of state-corporate crime. In: Schlegel K, Weisburd D (eds) White collar crime reconsidered. Northeastern University Press, Boston, pp 214–243

- Kramer R (2010) Resisting the bombing of civilians: challenges from a public criminology of state crime. Soc Justice 36(3):78–97

- Kramer R , Michalowski R (1990) Toward an integrated theory of state-corporate crime. Presented at the American Society of Criminology, Baltimore

- Kramer RC, Michalowski RJ (1991) State-corporate crime: case studies in organizational deviance. Unpublished manuscript

- Kramer R, Michalowski R (2005) War, aggression, and state crime: a criminological analysis of the invasion and occupation of Iraq. British J Criminol 45:446–469

- Matthews R, Kauzlarich D (2000) The crash of Valujet flight 592: a case study in state-corporate crime. Sociol Focus 33(3):281–298

- Michalowski RJ (1985) Order, law and crime. Random House, New York

- Michalowski RJ (2008) Power, crime and criminology in the new imperial age. Crime Law Soc Change 51:303–325

- Michalowski R (2009) Power, crime and criminology in the new imperial age. Crime Law Social Change 51(3–4):303–325(23)

- Michalowski RJ, Kramer R (1990) Toward an integrated theory of state-corporate crime. Paper presented at the American Society of Criminology, Baltimore

- Michalowski RJ, Kramer R (eds) (2006) State-corporate crime: wrongdoing at the intersection of business and government. Rutgers University Press, Piscataway

- Pearce F (1976) Crimes of the powerful. Pluto Press, London

- Rothe DL (2006) The Masquerade of Abu Ghraib: state crime, torture, and international law. PhD dissertation, Department of Sociology, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo

- Rothe DL (2009) The crime of all crimes: an introduction to state criminality. Lexington/Roman and Littlefield, Lanham

- Rothe DL (2010) Facilitating corruption and human rights violations: the role of international financial institutions. Crime, Law Soc Change 53(5):457–476

- Rothe DL, Kauzlarich D (2010) State-level crime: theory and policy. In: Barlow HD, Scott D (eds) Crime and public policy: putting theory to work, 2nd edn. Temple University Press, Philadelphia, pp 166–187

- Rothe DL, Mullins CW (2008) Genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity in Central Africa: a criminological exploration. In: Haveman R, Smeulers A (eds) Supranational criminology: towards a criminology of international crimes. Intersentia, Antwerp, pp 135–158

- Rothe DL, Mullins CW (2009) Toward a criminology of international criminal law: an integrated theory of international criminal law violations. Int J Comp Appl Crim Justice 33(1):97–118

- Rothe DL, Ross JI (2010) Private military contractors, crime, and the terrain of unaccountability. Justice Q 27(4):593–617

- Rothe DL, Mullins CW, Muzzatti S (2006) Crime on the high seas: crimes of globalization and the sinking of the Senegalese Ferry Le Joola. Crit Criminol Int J 14(2):159–180

- Rothe DL, Mullins CW, Sandstrom K (2009) The Rwandan Genocide: international finance policies and human rights. Soc Justice 35(3):66–86

- Shaw C, McKay HD (1942) Juvenile delinquency and urban areas. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Simon D (1999) Elite deviance, 6th edn. Allyn and Bacon, Boston

- Sutherland E (1949) White collar crime. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York

- Sykes G, Matza D (1957) Techniques of neutralization: a theory of delinquency. Am Sociol Rev 22:664–670

- Takaki R (1993) A different mirror: a history of multicultural America. Little Brown, Boston

- Vaughan D (1982) Toward understanding unlawful organizational behavior. Mich Law Rev 80:1377–1402

- Vaughan D (1992) The macro–micro connection in white-collar crime theory. In: Schlegel K, Weisburd D (eds) White collar crime reconsidered. Northeastern University Press, Boston, pp 124–145

- Vaughn D (1996) The challenger launch decision: risky technology, culture, and deviance at NASA. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.