This sample Criminal Career of Sex Offenders Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

The interest for the criminal career is not new and several commentaries and observations about sex offenders’ criminal activity have been made for quite some time. Most of these commentaries and observations were focused on the same underlying questions, that is, sex offenders’ dangerousness. The issue of dangerousness has been addressed by examining sex offenders’ likelihood of sexual recidivism using different methodologies. These descriptive studies of sex offenders’ criminal records were not supported by an organizing conceptual framework which led to the emergence of controversies among researchers about sex offenders’ nature and extent of their criminal behavior. These controversies certainly did not help to challenge common myths and false beliefs about sex offenders’ criminal behavior which have, in some instances, serve as the foundation to develop new criminal justice policies to tackle the problem of sexual violence and abuse. The current study aims to introduce the criminal career approach and, in doing so, aims to provide a common organizing framework for policy makers as well as researchers from various disciplines such as psychology, psychiatry, sociology, social work, criminal justice, and criminology. Although there is a long history of criminal career research with the publication of Criminal Careers and Career Criminals in 1986 by Dr. Al Blumstein and colleagues, such a framework was introduced to the field of criminal justice and criminology. The criminal career approach is concerned with the description and explanation of the longitudinal sequence of offending. While the criminal career approach has been around for quite some time in criminological circles, it would take some time, however, before this framework would be introduced more explicitly to the field of sexual violence and abuse (Blokland and Lussier 2012; Lussier et al. 2005). Building on the criminal career approach proposed by Blumstein and colleagues, the current review examines the current state of knowledge regarding the criminal activity of sex offenders. While the criminal career approach should not be seen as a cure-all approach, it provides a conceptual framework to organize existing study findings, to guide future empirical research, as well as to help to think more clearly about sex offenders’ criminal behavior. Therefore, this research paper aims, first, to introduce researchers from the field of sexual violence and abuse to the criminal career approach; second, to organize the empirical knowledge on the criminal activity of sex offenders using a criminal career approach; and, third, to review the state of empirical knowledge on various dimensions of the criminal career of sex offenders.

The Criminal Career Approach

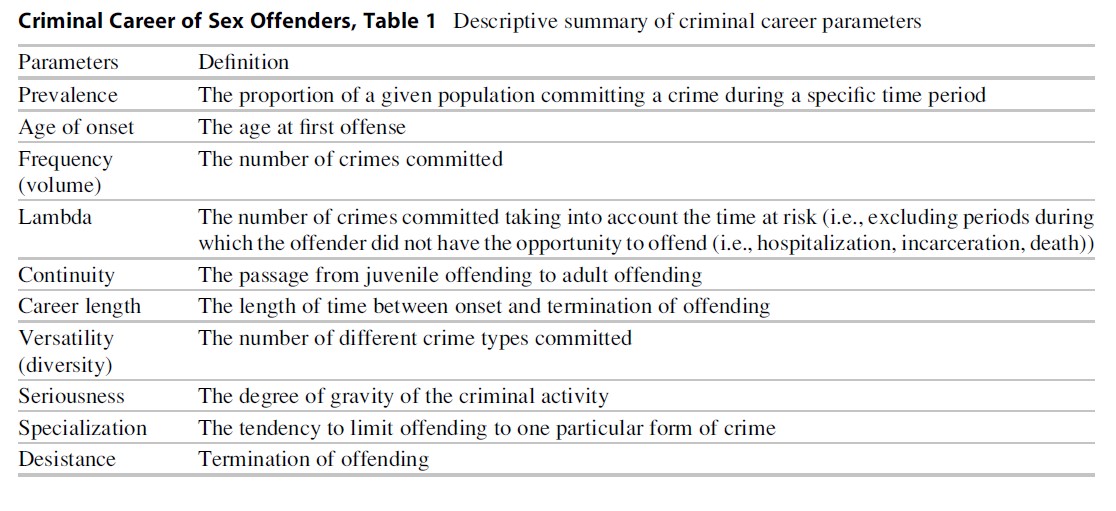

Over the past five or six decades, no other offender type has been under more scrutiny from researchers than sex offenders have been. Researchers from the field of sexual violence and abuse have measured a wide range of factors to describe individuals having committed sex crimes, such as family background, victimization experiences, exposure to deviant models, attachment bonds, parental practices, childhood behaviors, psychiatric symptoms, personality traits and disorders, intelligence and cognitive skills, sexual arousal and interests, mood and temperament, cognitive distortions, sexual development and sexual behaviors, coping skills and coping strategies, and pornography use, to name just a few. One striking observation that can be made is that while sex offenders have been described in so many ways along so many dimensions and factors, comparatively speaking, the very behavior that clinical researchers aimed to explain, sexual offending, has been largely neglected. This is not an overlooking but illustrates the fact that most theoretical views of sex offending is based on the assumptions that there is a stable propensity to commit sex crime and theoretical models should only be concerned by the description and the explanation of this propensity. These models, therefore, do not recognize the importance of distinguishing such aspects as prevalence, age of onset, persistence, frequency, seriousness, and desistence. This trait-like approach is not well suited to describe and explain why offenders start or stop offending and whether the same factors explain both. Some theoretical models do make distinction for various offending stages but have been limited to a few aspects of sex offending, such as onset and persistence (e.g., Marshall and Barbaree 1990). The criminal career approach provides a framework to think about how sexual offending starts, develops over time, and stops and whether such distinctions are theoretically, clinically, as well as policy relevant (Table 1).

The Onset Of Sex Offending

The age of onset of sex offending refers to the age at which sex offending is initiated. The age of onset is particularly interesting because it marks the origins of the behavior and allows examining why and under what circumstances the criminal behavior was initiated. The age of onset has been discussed in several empirical studies on sex offenders, but its operationalization has not always been clear and straightforward. In earlier investigations, clinical researchers have been concerned with the age of onset of sexual problems of adult offenders. Using the term sexual problems is problematic because it encompasses behaviors such as the onset of deviant sexual arousal, the onset of deviant sexual fantasizing, the onset of deviant sexual behaviors, as well as the onset of sexual offending. Early theoretical models put much great emphasis on the role of deviant sexual fantasies as a precursor to sexual offending. Clinical research, however, has shown that only a small proportion of adult offenders report deviant sexual fantasies and/or a paraphilia, and an even fewer proportion of them report having experienced such deviant fantasies prior their offending (Marshall et al. 1991). This reinforces the importance of distinguishing deviant fantasies, deviant sexual behaviors, and sex offending.

Early studies looking at the onset of sex offending has described adult sex offenders as grown-up juvenile sex offenders. For example, in the Prentky and Knight study (1993), 49 % of their sample of adult rapists reported an onset prior age 18, while the rest of the sample reported an onset in adulthood. These results mirror those reported in the Groth et al. study (1982), which showed an average age of onset of 19 years old for a sample of sexual aggressors against women, while in the Abel et al. (1993) study, it was 22 years old. The self-reported onset age for child molesters appears to be different than the one reported for rapists, but the findings are not stable across studies. In the Prentky et al. (1993) study, whereas 49 % of adult rapists were JSOs, that number increased to 62 % for child molesters. Therefore, given these results, one could expect that the average onset age for child molesters would be younger than the one reported for rapists. This is not the case and this could be attributable to sampling differences. More precisely, these earlier studies showed some discrepancies across child molester types. To illustrate, in the Marshall et al. (1991) study, the self-reported age of onset was 24 years old for extra-familial offenders against boys, 25 years old for extra-familial offenders against girls, and 33 years old for incestuous fathers. Similar numbers were reported by Smallbone and Wortley (2004) suggesting that the onset of extra-familial child molestation starts sooner than the onset of intrafamilial child molestation. These differences may be explained by opportunity structure of the offense as one needs to have a biological child to offend against him or her. These studies used retrospective data to estimate the age at which adult sex offenders started their offending behavior. From these self-report studies (see, e.g., Abel et al. 1993), however, it is not always clear whether the onset refers specifically to sex offending or to some other behavior such as the onset of deviant sexual interests, the onset of deviant sexual fantasizing, and the onset of deviant sexual arousal.

Not surprisingly, the age of onset based on self-report data is younger than those based on official data (e.g., Gebhard et al. 1965; Lussier et al. 2005; Smallbone and Wortley 2004). When looking at the official age of onset, results clearly indicate that it significantly varies across sex offender types. Reports suggest that sexual aggressors of women are typically charged for a first offense in their late twenties, while for sexual aggressors of children, it is typically in their late 30s. There is a gap between the age of onset reported in self-report studies with adult sex offenders and those found in studies based on police data. That gap, however, is relatively unknown given that self-report and official data on the age of onset are not typically analyzed in the same study limiting the conclusions that can be drawn. Further, the utility of other sources of information, such as the police report and the victim statement, has not been examined in prior research. Lussier and Mathesius (2012) provided evidence that the official age of onset, as measured with criminal justice data, provides a distorted view on the actual onset of offending, at least for some sex offenders. Their claim was based on the observation that official data of offending does not take into consideration the offender’s ability to avoid and/or delay detection. In their study, official data, police data, and victim’s account were analyzed to compare and contrast the official and actual age of onset. On average, it was found that there is a gap of about 7 years between actual and official age of onset in sex offending. The findings showed that the gap between actual and official onset was much more important for child molesters, more specifically incestuous and pseudo-incestuous fathers. These findings may suggest that victims may take significantly longer to report the crime to the authorities (if they do) when the crime is committed by a parental figure. For the most part, while the actual age of onset does not vary across sex offender types, it does for the official age of onset, suggesting differential investment in detection avoidance across offenders. Further, findings show that close to 20 % of sex offenders have already desisted or are in the process of desisting by the time they are first charged for their sex crime.

Frequency Of Sex Offending

Frequency of sex offending refers to the number of sex crimes committed. This refers to the offender’s volume of crimes. It is interesting to note that researchers have not spent much time describing this aspect of sex offender’s offending. Like many other crime types, measuring frequency of sex offending is not as straightforward as it may seem. This may be due to the nature of the offending behavior and various offending strategies adopted by sex offenders (Lussier et al. 2011). As such, frequency of sex offending may refer to the number of victims an individual has offended against. Frequency can also refer to the number of sex crime event, or the number of times an individual has sexually offended against a person. Some offenders may adopt an offending strategy in which different victims are offended against on a very limited number of occasions (once or twice). This victim-oriented strategy may characterize offenders who offend against strangers. Other offenders may decide to limit the number of victims they offend against choosing instead the maximization of a single offending opportunity by reoffending on multiple occasions against the same person. This strategy may be referred to as the event-oriented strategy and characterizes incest and pseudo-incest offenders as well as offenders offending against their partner. It is difficult to estimate the frequency of offending using available data found in past research because too often criminal justice indicators are used, such as the number of arrests (or convictions) for a sex crime. Such indicators may not reflect well the actual behaviors that lead to the arrest. For example, a sex offender may have been convicted once for sex crime which involves the abuse of a child over a 5-year period in which the victim was molested on more than 500 occasions. Relatedly, an individual may also have only one conviction for a sex crime that involves the rape of three women, each raped on a single occasion. Frequency can also be influenced by the time at risk or the time an offender was at risk of perpetrating a crime (e.g., not incarcerated, not hospitalized, not dead). As such criminal career researchers have used the term lambda or annual frequency of offending that takes into account the time at risk.

Empirical studies have shown much heterogeneity in the frequency of sex offending across sex offenders. In the Lussier et al. (2011) study using a sample of convicted adult male sex offenders, the average number of victim was 1.8, but the number of victims varied between one and 13. Similarly, Groth et al. (1982) reported that the number of self-reported sex crimes reported by their sample of sex offenders varied between one and 30. Even greater variance was found in the Weinrott and Saylor (1991) study where the range of self-reported victims varied between one and 200. Heterogeneity in the volume of sex offending can also be found across sex offender type. Such discrepancies between aggressors of women and children using official data were not found in the Weinrott and Saylor (1991) study. They found that on average, sexual aggressors of women had 1.8 victims, while it was 2.0 for child molesters. Similarly, Groth et al. (1982) using self-reported data found that rapists and child molesters had a similar average number of sex crimes (about five). This may have something to do with sample composition. Pham et al. (1999) also reported that their group of intra-familial offenders had a mean number of 1.6 victims, much lower than what was reported for extra-familial child molesters. Indeed, intra-familial child molesters tend to have a significantly lower number of victims (Abel et al. 1987). Intra-familial offenders’ lower average number of victims may be a function of structuring opportunity factors. Indeed, the average number of victims corresponds to the number of children typically found in contemporary western-country families. This may suggest that these offenders are less likely to offend outside the family setting. It may well be also that incestuous fathers are seeking event-oriented opportunity where they can maximize the number of offending opportunities against the same victim. It could be, therefore, that the sample used in the Weinrott and Saylor (1991) study included a high proportion of intra-familial child molesters.

Weinrott and Saylor (1991) study findings are also insightful about the sex offenders’ volume of sex offending because their study also used self-reported data. In other words, they asked these men to report their number of victims. Hence, while sexual aggressors of women had, on average, about two official victims, these men reported, on average, having offended against close to 12 victims. In other words, the mean number of self-reported victims was more than five times the number of official victims. It should be noted, however, that the median number of victims was 6, or three times the average number of official victims. The median is much lower than the mean, most probably because of the presence of small group offenders with a disproportionately high number of victims. The discrepancies between official and self-report data were also observed for child molesters. If their sample of child molesters had, on average, offended against two victims, these men reported having offended, on average, against seven victims. Similar numbers were reported by (Marshall et al. 1991) as well as by Groth et al. (1982). Nonetheless, the number of self-reported victims reported in the Weinrott and Saylor study is a far cry from those reported by Abel et al. (1987). The Abel et al. study reported that extra-familial offenders against girls had about 20 victims on average, while for extra-familial offenders against males, it was 150. Note that the median numbers of victims for the two groups were 1 and 4, suggesting that 50 % of their sample of extra-familial offenders against girls self-reported only one victim, while 50 % of the sample of extra-familial offenders against boys reported no more than four victims. Perhaps, for some reasons, a small group of offenders included in the Abel et al. (1987) exaggerated the volume of their offending. Hence, while Abel et al.’s (1987) mean number of victims looks impressive, the inspection of the median suggests that most child molesters, to the exception of those offending against boys outside the family setting, typically offend against a single victim. This is not meant to say that there are no prolific sex offenders.

Lussier et al. (2011) investigated the presence of prolific offenders in a sample of adult males convicted for a sex crime. Using several sources of information (self-report, police investigation, victim statement), the frequency of offending (and lambda) was estimated. The study was insightful about the presence of prolific sex offenders for several reasons. The authors examined frequency in terms of the number of sex crime events offenders had been involved in. The study findings highlighted that about 11 % of their sample had been involved in over 300 sex crime events as opposed to about 40 % who had been involved in only one crime event. There were no differences in the number of different victims offenders of both groups had offended against, suggesting that maximizing the number of victims is independent of the offender’s decision to maximize the number of crime events. In other words, some offenders take advantage of low-risk short-term opportunities with different victims, while others opt to benefit from a single offending opportunity by repeatedly offending against the same victim over and over. The findings revealed that the most prolific sex offenders were older and had a more conventional background characterized by a stable relationship with an adult partner, a job at the time of the offense(s), no drug issues, and no prior record for a sex crime. The convention image of the prolific sex offender contrasts with the typical image of the chronic offender stemming from empirical research with prison populations of general offenders as someone who is young, single, unemployed, has significant alcohol and/or drug issues, and a lengthy criminal record. The findings of (Lussier et al. 2011) also contrast with the media portrayal of the “sexual predator.”

Continuity In Sex Offending

Continuity refers to the persistence of sex offending from adolescence to adulthood. Continuity, therefore, informs about the proportion of juvenile sex offenders who become adult sex offenders as well as the proportion of adult sex offenders who were juvenile sex offenders. The continuity hypothesis stipulates that today’s juvenile sex offenders are tomorrow’s adult sex offenders, and several policies are based on this assumption. The discontinuity however suggests that most juvenile sex offenders do not go on to become adult sex offenders and that, for the most part, juvenile sex offenders’ offending behavior is limited to the period of adolescence. The lesson learned from criminal career research is that retrospective data with samples of adult offenders tend to overestimate continuity of offending because such studies fail to include youths who have desisted from offending in adolescence. It is well accepted by criminologists that there is much discontinuity in antisocial behavior, but antisocial personality disorder in adulthood virtually requires antisocial behavior in youth. Whether this conclusion applies also to sex offending is unclear. It has in fact been argued that JSOs do not continue their sexual offending in adulthood. While this is certainly true for most JSOs, empirical studies indicate that a small fraction (between 5 % and 10 %) may indeed continue their sexual offending in young adulthood (e.g., Lussier et al. 2012). The proportions of JSOs continuing in adulthood gradually increase with a longer follow-up period in adulthood (between 10 % and 15 %) (e.g., Hagan et al. 2001). Bremer (1992) reported a 6 % reconviction rate in a sample of serious JSO, but the recidivism rate rose to 11 % when based on self-reports. Therefore, while the use of official data underestimates recidivism rates, it is unlikely to be able to explain the fact that the vast majority are not rearrested or caught again for a sex crime. Taken together, there appears to be sizeable discontinuity in sexual offending from adolescence to adulthood superimposed on a little continuity. Hence, while aggregate data indicate that the overwhelming majority of juveniles do not persist their sexual offending in adulthood, it does not inform practitioners and policy makers about those few juvenile offenders who do persist.

Versatility In Sex Offending

Versatility refers to offenders’ tendency to commit a wide array of offenses. Criminal versatility is concerned with the crime-switching patterns of offenders as offending persists over time. Two types of crime-switching patterns can be distinguished. First, crime-switching can be analyzed in the context of sex offenders’ whole criminal activity. Hence, from that perspective, researchers are concerned with the number of different types of non-sex crimes sex offenders are involved in. An underlying theme would be to examine the crime mix, or the nature of the different types of criminal activities characterizing sex offenders’ criminal repertoire. The scientific literature on the criminal versatility of sex offenders has been described in details elsewhere (e.g., Lussier et al. 2005). Secondly, crime-switching can also be examined strictly in the context of sexual offending. This would refer to sex offenders’ tendency to limit themselves to one form of sex crimes. Within the context of sex offending, crime-switching patterns can occur along several dimensions such as victim’s age, gender, relationship to the offender, nature of sexual acts committed by the offender, and level and type of coercion used. Others have also used the term sexual polymorphism to describe a sexual criminal activity characterized by much versatility (see Guay et al. 2001; Lussier et al. 2008). Few studies have examined the level of sexual polymorphism and crime-switching patterns in the sexual criminal activity of persistent sex offenders. Based on the current state of knowledge, there are three broad conclusions that can be drawn in regard to the offending pattern of persistent sexual offenders.

First, Soothill and colleagues came to the conclusion that while sex offenders are generalists in their criminal offending, they tend to specialize in their sexual offending, confining themselves to one victim type (Soothill et al. 2000). Similarly, (Radzinowicz 1957) also found specialization in victim choice in that only 7 % of his large sample of sex offenders had convictions for crimes against both male and female victims, a finding consistent with those of Gebhard et al. (1965). More recently, Cann et al. (2007) found that only about 25 % of their sample of incarcerated sex offenders was versatile when considering victim’s age and gender as well as the offender-victim relationship. On the other hand, crime-switching patterns may vary as a function of the dimension of the sexual polymorphism considered. For instance, while they also found much stability as to the victim’s gender, Guay et al. (2001) reported considerable versatility for those targeting adolescents. While offenders targeting children and those targeting adults remained in the same category, those offending against adolescents were likely to switch either to adults or to children. (Guay et al. 2001) hypothesized that adolescents may be a sex surrogate choice when the preferred partner was not available.

Empirical studies conducted in clinical settings have shown a divergent picture of the sex offenders’ crime-switching pattern. Weinrott and Saylor (1991) as well as Heil et al. (2003) have argued that official data hide an enormous amount of sex crimes. Using official data only, Weinrott and Saylor (1991) found that only 15 % of their sample of offender was versatile considering only three categories: adult female, extra-familial children, and intra-familial children. Using a self-reported computerized questionnaire, however, that number rose to 53 %. Similarly, (Heil et al. 2003) reported that incarcerated offenders in treatment are not versatile as to victim’s age (7 %) and gender (8.5 %) when assessed with official data but are when interviewed using a polygraph (70 % and 36 %, respectively). Less dramatic numbers were reported for parolees which might be explained by sampling differences (i.e., incarcerated offenders were more serious offenders) and the fact that admitting a crime was a prerequisite to enter treatment. Abel’s well-known study conducted under strict conditions of confidentiality showed that 42 % of their sample targeted victims in more than one age group, 20 % targeted victims of both gender, and 26 % committed both hands-on and hands-off crimes (Abel and Rouleau 1990). Similar results have been reported elsewhere in a sample of sex offenders assessed in a forensic psychiatric institution (Bradford et al. 1992).

The overlapping nature of different forms of sexually deviant acts found in the clinical studies is counterintuitive to current typological models of sex offenders based on the characteristics of the offense. The victim’s gender, the victim’s age, the offender-victim relationship, the level of sexual intrusiveness, and the level of force used during the commission of the crime are some examples of criteria that have been used over the years to classify sex offenders (e.g., Gebhard et al. 1965; Knight and Prentky 1990). Smallbone and Wortley (2004) came to the conclusion that diversity in paraphilic activities may be a function of general deviance. Indeed, looking at different activity paraphilia (e.g., voyeurism, frotteurism, sexual sadism) in a sample of child molesters, they found that a scale measuring the versatility of sexual deviance correlated significantly and positively with nonsexual offending. In other words, as the frequency of offending increases, so does the versatility in paraphilic interests and behaviors. Similarly, (Lussier et al. 2005) found in a sample of adult sex offenders that versatility in sex offending was strongly related to versatility in nonsexual nonviolent offending as well as versatility in nonsexual violent crime. Furthermore, using structural equation modeling, they found that such pattern of general versatility was related to an early onset and persistence of antisocial behavior. In other words, sex offenders characterized by a life-course-persistent antisocial tendency were more likely to show much versatility in their sexual offending. In that regard, (Guay et al. 2001) hypothesized that crime-switching in sexual offending might be partly explained by low self-control.

Lussier et al. (2008) analyzed crime-switching patterns of a sample of convicted adult sex offenders using transition matrices and diversity indexes. They observed that crime-switching in sex offending is multidimensional in that diversity index tends to be relatively independent from one another. In other words, if an offender offends against victims from different age groups, it does not imply that this person will offend against both males and females. Therefore, contrary to Abel and Rouleau (1990) conclusions, little evidence was found suggesting that sex offenders are sexual deviates offending against different types of victims in different contexts. Furthermore, the study findings highlighted that crime-switching patterns vary across dimensions of sex crimes. On the one end of the continuum, victim’s gender and level of physical force are relatively stable across crime transitions. The notion of preference is relevant and of importance in the understanding of persistence in sexual offending. The study findings were in line with those of Soothill et al. (2000) suggesting that some specialization can be found for certain aspects of sex offending and that some aspects of offending are far from being random upon certain situational contingencies. On the opposite end of the continuum, the victim’s age and sexual intrusiveness involve more crime-switching. In other words, sex offenders are not prone to switching from males to female victims (and vice versa) or to change their level of violence across offenses. It is the nature of sexual acts (hands-on, hands-off, oral sex, penetration) and victim’s age that tend to fluctuate the most across the longitudinal sequence of sex crimes committed by sex offenders. The concept of sex surrogate might also play a part in stimulating crime-switching (Guay et al. 2001). This appears to be especially true for those having offended against adolescent victims, who might represent the second best option in the absence of the preferred victim type (i.e., children or adults). This situation appears to be true for both child molesters and rapists. Of importance, and in keeping with the sex surrogate hypothesis, is that very few child molesters also offended against adults and vice versa. Finally, the study highlighted that crime versatility in sex offending tends to increase as a function of persistence of sex offending, especially for victim’s age, offender-victim relationship, and sexual intrusiveness. Hence, the more sex offenders offend against different victims, the more their sexual criminal repertoire will diversify along those dimensions. This might partly explain discrepancies reported in earlier studies as clinical samples including more serious and persistent offenders should report more evidence of crime-switching.

Specialization In Sex Offending

Crime specialization is another important aspect of the criminal career of sex offenders. Various definitions of crime specialization have been proposed over the years. Criminal career researchers have generally defined specialization as the probability of repeating the same type of crime (Blumstein et al. 1986). Crime specialization is important from a crime control perspective for obvious reasons. If offenders do specialize in a particular crime type, then it gives support to the implementation of crime prevention strategies targeting known offenders involved in such crime type. The sex offender registry is an example of assuming that sex offenders are sex crime specialists. Recording personal information in a database helping to track down convicted sex offenders is considered useful from a law enforcement standpoint. It can be used as a tool to prioritize suspect by assisting in the criminal investigation of new cases of sexual assault and abuse. According to the specialization hypothesis, if the criminal activity of a sexual offender persists, it would be primarily in sexual crime. Crime specialization is understood as the tendency for some crime to involve a higher or lower level of repetition over time. In that context, researchers may be interested in comparing whether specialization in sex crime is similar or different than specialization in burglary, drug-related offenses, driving under the influence, auto-theft, etc. The concept of crime specialist, on the other hand, refers to individuals with a higher probability of repeating the same crime over time. In that context, researchers may be interested in determining the proportion of sex crime specialists among sex offenders and their characteristics. Specialization can be studied in two contexts: (a) whether sex offenders tend to specialize in the type of sex crime they commit (e.g., Soothill et al. 2000; Lussier et al. 2008) and (b) whether sex offenders tend to specialize is sex crimes when considering their whole criminal activity. The latter has been the subject of closer empirical scrutiny by researchers.

Lussier (2005) reviewed the scientific literature on crime specialization in sex offending and concluded that empirical studies have provided little empirical evidence supporting the specialization hypothesis (see also Simon 1997). More precisely, sex offenders do not limit themselves to sex crimes, quite the contrary. This is not to say that all sex offenders are criminally versatile or that sex offenders’ criminal record always includes other crime types. Sex offenders who have a persistent criminal activity tend to be involved in other crime types that are not sexual in nature. This conclusion, however, requires closer scrutiny. Recidivism studies do show that sex offenders have a greater likelihood of being rearrested for a sex crime than non-sex offenders are. For example, in the (Langan et al. 2003) study, using a 3-year follow-up of close to 270,000 prisoners, 5 % of ASOs were rearrested for a sex crime compared to 1 % for non-sex offenders. These results do not take into account the fact that the recidivism rates significantly vary across sex offenders. For example, Quinsey et al. (1995) showed that for comparable follow-up periods, the sexual recidivism rate of incest offenders was 8 % as opposed to 18 % for child molesters offending against girls and 35 % for child molesters offending against boys.

Recidivism studies are impacted measures of crime specialization because it does not consider the whole criminal activity of an offender but only two successive crimes. Others have used transition matrices and have reported on the probabilities of being rearrested for a sex crime while taking into account the offender’s entire criminal career. Results have shown that crime specialization is much lower for rape (e.g., Blumstein et al. 1988) than when using a broader definition of sex crimes that includes child molestation (e.g., Stander et al. 1989). This suggests that child molesters are more likely to specialize in sex crimes than rapists. Such conclusion seems to be reinforced by the analysis of their criminal record and the importance of sex crimes in their entire criminal activity. Indeed, studies have shown that sex crimes represent about 4–14% of the entire criminal activity of rapists, while it is about 40 % for child molesters (Gebhard et al. 1965; Lussier et al. 2005). These numbers should be seen as tentative given the small number of studies having examined specialization in sex crime using a ratio of sex crimes to all crimes committed by sex offenders.

Desistance From Sex Offending

The study of the criminal career of sex offenders is still in its infancy. Not surprisingly, therefore, several dimensions of the criminal career of sex offenders have not been subject of much empirical research. Of importance, patterns of escalation and de-escalation in sex offending have been largely overlooked. Another key criminal career dimension that has been overlooked until recently is desistance (e.g., Kruttschnitt et al. 2000; Laws and Ward 2011). Desistance refers to the termination of the criminal career and can be understood here as the termination of sex offending.

The concept of desistance is important to describe the age at which sex offenders stop their sex offending; it allows us to determine the length of sexual offending, whether desistance from sex offending is accompanied by desistance in other crime types. Criminal career researchers understand desistance as a discrete event (the period after which offending has stopped). Develop-mentalists, however, understand desistance as a dynamic process by which offending slows down and becomes more specialized until complete termination. Studies having discussed the issue of desistance in the context of sex offending have generally relied on sexual recidivism indicators to determine desistance, that is, desistance is implied for the absence of a new charge or conviction during the follow-up period. This approach is somewhat misleading because with a longer follow-up period, offender considered to be desistors may become sexual recidivists. Recidivism is also problematic in the context where desistance is seen as a process as the presence of a new conviction for a sex crime may not inform about whether or not offending is less frequent and less serious over time.

In the field of sexual violence and abuse, desistance has generally been discussed in terms of the presence (or absence) of an age effect on the risk of sexual recidivism (Lussier and Healey 2009). In other words, it is possible that with age, aging, and the passage of time, sex offender’s propensity to commit a sex crime changes. Researchers generally agree on the recidivism rates of the younger adult offenders and older offenders, but there is controversy about the age effect occurring for other offenders. Three main points have been at the core of the debate about the link between aging and reoffending in adult offenders: (a) identification of the age at which the risk of reoffending peaks, (b) how to best represent the trend in risk of reoffending between the youngest and the oldest group, and (c) the possibility of differential age-crime curves of reoffending. One hypothesis states that, when excluding the youngest and oldest group of offenders, age at release and the risk of sexual recidivism might be best represented by a plateau. Thornton (2006) argued that the inverse correlation revealed in previous studies may have been the result of the differential reoffending rates of the youngest and oldest age groups, rather than a steadily declining risk of reoffending. In this regard, one study presented sample statistics suggesting a plateau between the early 20s and the 60s+ age groups (Langan et al. 2003) No statistical analyses were reported between the groups, thus limiting possible conclusions for that hypothesis. Another hypothesis suggested there might be a curvilinear relationship between age at release and sexual recidivism, at least for a subgroup of offenders. (Hanson 2002) found evidence of a linear relationship for rapists and incest offenders, and a curvilinear relationship was found for extrafamilial child molesters (see also Prentky and Lee 2007). Whereas the former two groups showed higher recidivism rates in young adulthood (i.e., 18–24), the latter third group appeared to be at increased risk when released in the subsequent age bracket (i.e., 25–35). This led researchers to conclude that, although rapists are at highest risk in their 20s, the corresponding period for child molesters appears to be in their 30s. These results, however, have been criticized on methodological grounds, such as the use of small samples of offenders, the presence of a small base rate of sexual reoffending, the use of uneven width of age categories to describe the data, the failure to control for the time at risk after release, and the number of previous convictions for a sexual crime (Barbaree et al. 2003; (Thornton 2006). The controversy over the age effect led researchers to question whether risk assessors should consider the offender’s age at the time of prison release and, if so, how the adjustment should be done (Barbaree et al. 2007; Harris and Rice 2007).

Subsequently, two prominent schools of thought emerged, and two main hypotheses have been used to describe and explain the roles of propensity, age, and reoffending in sexual offenders: (a) the static-maturational hypothesis and (b) the static-propensity hypothesis. The static-maturational hypothesis suggests that sex offenders’ risk of reoffending is subject to a maturation effect, as this risk typically follows the age-crime curve (Barbaree et al. 2007; Lussier and Healey 2009). Importantly, the maturation hypothesis is based on the assumption of a stable propensity to reoffend, but the offending rate can change over life course. In other words, the rank ordering of individuals (between-individual differences) on a continuum of risk to reoffend remains stable, but the offending rate decreases (within-individual changes) in a similar fashion across individuals. It was determined that the offender’s age at release contributes significantly to the prediction of reoffending, over and above scores of various risk factors said to capture sex offenders’ propensity to reoffend. Multivariate analyses showed that when controlling for prior criminal history, the rate of sexual reoffending decreases by about 2 % for every 1-year increase of the offender’s age at release (Thornton 2006). Adjusting for sociodemographic and criminal history factors, (Meloy 2005) replicated this finding for probation failure and for nonsexual reoffending, but not for sexual reoffending. This could be explained by the low base rate of sexual reoffending for this sample (i.e., 4.5 %). Other studies indicated that age at release contributes significantly to the prediction of reoffending, even after adjusting for actuarial scores (e.g., Barbaree et al. 2003). Similar to (Thornton 2006; Hanson 2006) reported that after adjusting for the scores on Static-99, the risk of sexual reoffending decreased by 2 % for every 1-year increase in age after release. No interaction effects were found between scores of the Static-99 and age at release. Though these preliminary results provide evidence in favor of the maturational hypothesis, many questions remain unanswered. The key question is whether sex offenders identified as high risk are also subject to an age effect. Because previous studies did not test the maturational hypothesis separately for high-risk offenders and considering that high-risk sex offenders constitute only a small minority of all convicted sex offenders, researchers might have been limited in finding a differential age effect.

The static-propensity hypothesis suggests that, by using historical and relatively unchangeable factors, adult sex offenders can be distinguished based on their likelihood of reoffending. The main assumption is that criminal propensity is stable over life course, and therefore, risk assessment tools should only be used for measuring the full spectrum of this propensity. An important point of contention for the static-propensity hypothesis is whether younger offenders at high risk to reoffend show the same or similar recidivism rates as older offenders with the same risk to reoffend. According to the static-propensity hypothesis, older offenders with high scores on risk assessment tools represent the same risk of reoffending as younger offenders with similar scores (e.g., Harris and Rice 2007). For static-propensity theorists, the only age factor that risk assessors should include are those reflecting a high propensity to reoffend, such as the age of onset of the criminal activity. For example, Harris and Rice (2007) argued that the effect of aging on recidivism is small. In fact, they argued that age of onset is a better risk marker for reoffending than age at release. In other words, those who start their criminal career earlier in adulthood show an increased risk of reoffending. Their findings showed that the offender’s age at release did not provide significant incremental predictive validity over actuarial risk assessment scores (i.e., VRAG) and age of onset. This could be partly explained by the fact that age of onset and age at release were strongly related, that is, early-onset offenders are more likely to be released younger than late-onset offenders. The high covariance between these two age factors might have limited researchers in finding a statistical age at release effect in multivariate analyses. Furthermore, (Barbaree et al. 2007) found that, after correcting for age at release, the predictive accuracy of actuarial tools significantly decreased, suggesting that an age effect was embedded in the risk assessment score. Actuarial tools have developed by identifying risk factors that are empirically linked to sexual reoffending. If the risk of reoffending peaks when offenders are in their 20s, it stands to reason that characteristics of this age group are most likely to be captured and included in actuarial tools. Consequently, scores of risk assessment tools might be more accurate with younger offenders but overestimate the risk of older offenders.

The findings of Lussier and Healey (2009) were generally consistent with the age-crime curve. Most sex offenders do not reoffend sexually after being released from prison and the Lussier and Healey (2009) study provided additional evidence of this. Congruent with the findings of Kruttschnitt et al. (2000), their finding was further evidence against the argument that sex offenders respond to nothing but long-term imprisonment and intensive community supervision. All offenders eventually desist, albeit at a different rate. The factors or the mechanisms explaining desistance remain tentative (Laws and Ward 2011). To illustrate the importance of age on desistance, Lussier and Healey (2009) compared the predictive accuracy of the offender’s age at release to that of the scores of an actuarial tool (i.e., Static-99) that includes one item reflecting the offender’s age at release. The findings showed that, by itself, age at release was as good a predictor of reoffending as the score of the Static-99, an actuarial tool designed to determine the risk of reoffending in sexual offenders. These results suggest that the offender’s age at release should be an important component considered by risk assessors when considering cases for long-term incapacitation and intensive community supervision. It is plausible that even if the agecrime association is quite general, it is not necessarily invariant and some offenders might deviate from that pattern. Hence, it is possible that the age effect might not operate the same way for individuals characterized by different offending trajectories. Future studies should examine whether the age-crime curve is present for sex offenders characterized by different offending trajectories and whether the age effect has the same impact on sexual recidivism across these groups. The results of the Lussier and Healey (2009) study do not provide empirical evidence for a strategy of selective incapacitation aimed at sex offenders but rather highlight the limited understanding of the role of aging and the process of desistance in sex offenders.

Conclusion

The study of sex offenders’ criminal activity using a criminal career approach is still in its infancy. Therefore, the conclusions drawn here should be interpreted accordingly. Longitudinal studies have shown that most juvenile sex offenders do not become adult sex offenders. In fact, studies suggest that about 10 % of convicted juvenile sex offenders become adult sex offenders. Similarly, retrospective longitudinal studies with adult sex offenders suggest that most adult sex offenders were not previously juvenile sex offenders. Said differently, there is not much continuity in sex offending from adolescence to adulthood. Such continuity appears to be more important for sample of adult sex offenders sampled in maximum-security psychiatric hospital suggesting that continuity in sex offending is associated with a mental health disorder. Empirical studies suggest, therefore, that the onset of sex offending for the majority of adult offenders occurs in adulthood. The investigation of the onset of offending shows a gap of about 7 years between the actual onset of sex offending and the age at first conviction for a sex crime. This gap varies across sex offender type. While there are not much age differences in terms of the actual onset of sex offending, there are differences in terms of age at first conviction for a sex crime. Child molesters are more likely to be first convicted for a sex crime later than sexual aggressors of women. Such differences may explain why child molesters are often found to be older than sexual aggressors of women and are most probably due to the fact that child molesters go undetected for longer time periods than sexual aggressors of women. The study of offending frequency reveals that most sex offenders will commit one crime against a single victim. Of those who persist, studies reveal two main offending strategies: one based on maximizing the number of victims (victim-oriented), while the other is based on maximizing the number of events (event-oriented). Those opting for a victim-oriented strategy tend not to reoffend against the same victim, while those following an event-oriented strategy will target few victims that will be abused repeatedly, sometimes over long time periods that can span over a decade. The study of desistance suggests that all sex offenders eventually desist from sex offending but at a different rate. Empirical research also suggests that age and aging does impact sex offender’s risk of reoffending over time in a traditional fashion. Older sex offenders have a significantly lower probability of reoffending than younger offenders, yet the criminal justice system is often imposing the most stringent conditions and sentences to older offenders which may impact their ability for successful community reintegration. Such conclusions, however, are based on official data on recidivism and subject to known limitations about official statistics on crime. Using other sources of information in future research to measure crime represents an important challenge for researchers in the field of sexual violence and abuse. Greater understanding of the criminal career of sex offenders will inform policy makers about these offenders’ pattern of offending over time but also how to best tackle the problem of sexual violence and abuse.

Bibliography:

- Abel GG, Becker JV, Mittleman MS, Rouleau JL, Murphy W (1987) Self-reported sex crimes of non-incarcerated paraphiliacs. J Interpers Violence 2:3–25

- Abel GG, Rouleau JL (1990) The nature and extent of sexual assault. In: Marshall WL, Laws DL, Barbaree HE (eds) Handbook of sexual assault: issues, theories, and treatment of the offender. Plenum Press, New York, pp 9–21

- Abel G, Osborn CA, Twigg DA (1993) Sexual assault through the life span: adult offenders with juvenile histories. In: Barbaree HE, Marshall WL, Hudson SM (eds) The juvenile sex offender. Guilford, New York, pp 104–117

- Barbaree HE, Blanchard R, Langton CM (2003) The development of sexual aggression through the life span. Ann N Y Acad Sci 989:59–71

- Barbaree HE, Langton CM, Blanchard R (2007) Predicting recidivism in sex offenders using the VRAG and SORAG: the contribution of age-atrelease. Int J Forensic Ment Health 6:29–46

- Blokland A, Lussier P (2012) Sex offenders: a criminal career approach. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford

- Blumstein A, Cohen J, Roth JA, Visher CA (1986) Criminal careers and “career criminals”. National Academy Press, Washington, DC

- Blumstein A, Cohen J, Das S, Moitra SD (1988) Specialization and seriousness during adult criminal careers. J Quant Criminol 4:303–345

- Bradford JM, Boulet J, Pawlak A (1992) The paraphilias: a multiplicity of deviant behaviours. Can J Psychiat 37:104–108

- Bremer JF (1992) Serious juvenile sex offenders: treatment and long-term follow-up. Psychiatr Ann 22:326–332

- Cann J, Friendship C, Gozna L (2007) Assessing crossover in a sample of sexual offenders with multiple victims. Leg Criminol Psychol 12:149–163

- Gebhard PH, Gagnon JH, Pomeroy WB, Christenson CV (1965) Sex offenders: an analysis of types. Harper & Row, New York

- Groth AN (1982) The incest offender. In: Sgrol SM (ed) Handbook of clinical intervention in child sexual abuse. D.C. Heath and Co, Lexington, pp 215–239

- Guay JP, Proulx J, Cusson M, Ouimet M (2001) Victimchoice polymorphia among serious sex offenders. Arch Sex Behav 30:521–533

- Hagan MP, Gust-Brey KL, Cho ME, Dow E (2001) Eightyear comparative analyses of adolescent rapists, adolescent child molesters, other adolescent delinquents, and the general population. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 45:314–324

- Hanson RK (2002) Recidivism and age: follow-up data from 4673 sexual offenders. J Interpers Violence 17:1046–1062

- Hanson RK (2006) Does static-99 predict recidivism among older sexual offenders? Sex Abuse-J Res Treat 18:343–355

- Harris GT, Rice ME (2007) Adjusting actuarial violence risk assessments based on aging or the passage of time. Crim Justice Behav 34:297–313

- Heil P, Ahlmeyer S, Simons D (2003) Crossover sexual offenses. Sex Abuse: J Res Treat 15:221–236

- Knight RA, Prentky RA (1990) Classifying sexual offenders: the development and corroboration of taxonomic models. In: Marshall WL, Laws DR, Barbaree HE (eds) Handbook of sexual assault: issues theories and treatment of the offender. Plenum Press, New York, pp 23–54

- Kruttschnitt C, Uggen C, Shelton K (2000) Predictors of desistance among sex offenders: the interaction of formal and informal social controls. Justice Q 17:61–87

- Langan PA, Schmitt EL, Durose MR (2003) Recidivism of sex offenders released from prison in 1994. US Department of Justice, Washington, DC

- Laws DR, Ward T (2011) Desistance from sex offending: alternatives to throwing away the keys. Guildford, New York

- Lussier P, Healey J (2009) Rediscovering Quetelet, again: the “aging” offender and the prediction of reoffending in a sample of adult sex offenders. Justice Q 26:827–856

- Lussier P, Mathesius J (2012) Criminal achievement career initiation and cost avoidance: the onset of successful sex offending. J Crime Justice, in press

- Lussier P (2005) The criminal activity of sexual offenders in adulthood: Revisiting the specialization debate. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment 17:269–292

- Lussier P, LeBlanc M, Proulx J (2005) The generality of criminal behavior: a confirmatory factor analysis of the criminal activity of sexual offenders in adulthood. J Crim Justice 33:177–189

- Lussier P, Leclerc B, Healey J, Proulx J (2008) Generality of deviance and predation: crime-switching and specialization patterns in persistent sexual offenders. In: Delisi M, Conis P (eds) Violent offenders: theory, public policy and practice. Jones and Bartlett Publishers, Boston, pp 97–140

- Lussier P, Bouchard M, Beauregard E (2011) Patterns of criminal achievement in sexual offending: unravelling the “successful” sex offender. J Crim Justice 39:433–444

- Lussier P, van den Berg C, Bijleveld C, Hendriks J (2012) A developmental taxonomy of juvenile sex offenders for theory research and prevention: the adolescent-limited and the high-rate slow desister. Crim Justice Behav, in press

- Lussier P, Mathesius J (2012) Criminal achievement, career initiation, and cost avoidance: The onset of successful sex offending. J Crim Justice 35: 376–394

- Lussier P, van den Berg C, Bijleveld C, Hendriks J (2012) A developmental taxonomy of juvenile sex offenders for theory, research and prevention: The adolescent-limited and the high-rate slow desister. Crim Justice Behav 39:1559–1581

- Marshall WL, Barbaree HE (1990) An integrated theory of the etiology of sexual offending. In: Marshall WL, Laws RD, Barbaree EH (eds) Handbook of sexual assault: issues, theories, and treatment of the offender, applied clinical psychology. Plenum Press, New York, pp 257–275

- Marshall WL, Barbaree HE, Eccles A (1991) Early onset and deviant sexuality in child molesters. J Interpers Violence 6:323–335

- Meloy ML (2005) Sex offender next door: an analysis of recidivism, risk factors, and deterrence of sex offenders on probation. Crim Justice Policy Rev 16:211–236

- Pham TH, DeBruyne I, Kinappe A (1999) E´ valuation statique des de´lits violents chez les de´linquants sexuels incarce´re´s en Belgique francophone. Criminologie 32:117–125

- Prentky RA, Knight RA (1993) Age of onset of sexual assault: criminal and life history correlates. In: Hall GCN, Hirschman R, Graham J, Zaragoza MS (eds) Sexual aggression: issues in etiology assessment, and treatment. Taylor & Francis, Washington, DC, pp 43–62

- Prentky RA, Lee AFS (2007) Effect of age-at-release on long term sexual re-offense rates in civilly committed sexual offenders. Sex Abuse: J Res Treat 19:43–59

- Quinsey VL, Lalumie`re ML, Rice ME, Harris GT (1995) Predicting sexual offenses. In: Campbell JC (ed) Assessing dangerousness: violence by sexual offenders, batterers, and child abusers. Sage, Thousand Oaks, pp 114–137

- Radzinowicz L (1957) Sexual offences: a report of the Cambridge department of criminal justice. Macmillan, London

- Smallbone SW, Wortley RK (2004) Onset, persistence, and versatility of offending among adult males convicted of sexual offenses against children. Sex Abuse: J Res Treat 16:285–298

- Simon L (1997) The myth of sex offender specialization: An empirical analysis. New England Journal on Criminal and Civil Commitment 23:387–403

- Soothill K, Francis B, Sanderson B, Ackerley E (2000) Sex offenders: specialists, generalists or both? Br J Criminol 40:56–67

- Stander J, Farrington DP, Hill G, Altman PME (1989) Markov chain analysis and specialization in criminal careers. Br J Criminol 29:317–335

- Thornton D (2006) Age and sexual recidivism: a variable connection. Sex Abuse: J Res Treat 18:123–135

- Weinrott MR, Saylor M (1991) Self-report of crimes committed by sex offenders. J Interpers Violence 6:286–300

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.