This sample Eysenck’s Personality Theory Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Overview

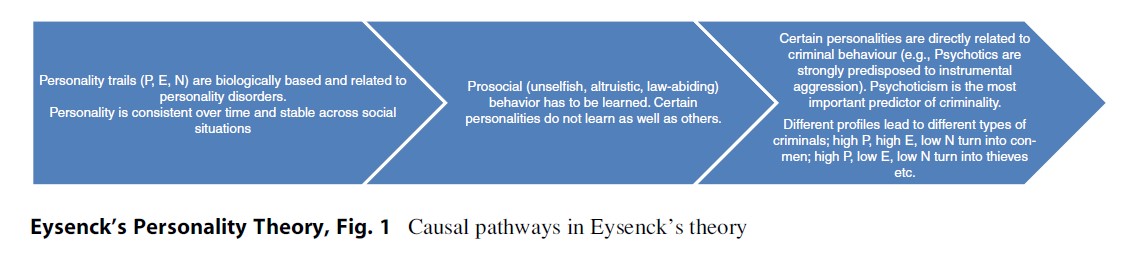

This research paper looks at the research on personality correlates and determinants of crime following the influential views of the late Hans Eysenck. Eysenck, a differential psychologist, made a strong theory and empirically based claim for the idea that personality factors of individuals make them more likely to take part in delinquent and criminal acts. The theory is reviewed and critiqued.

Introduction

Hans Eysenck was perhaps the most prolific psychologist of his day and is still one of the most quoted in the world. Prof. Jeffrey Gray, student of and successor to Hans Eysenck, once famously described his personality theory as akin to somebody finding St. Pancras Railway Station in the jungle. The station is an extremely impressive piece of highly elaborate, complex, and beautiful Victorian architecture situated in central London. What Gray meant was that Eysenck’s theory stands out dramatically from all around it.

It has been argued that Eysenck’s approach to science was characterized by very specific principles (Netter 2007). First, he always argued, even at a time when this was deeply unfashionable, that there was a physical/biological basis to personality. He maintained that taxonomization was the beginning of science and that personality research could not proceed without it. He insisted on a hierarchical model with highly specific behavioral responses at the lowest level, leading up to broad habitual responses at the facet level (e.g., sociability, liveliness, and excitability) and culminating into three giant super-factors at the apex of the hierarchy. He was one of the earliest theorists to advocate a biologically based theory of personality and to promote a continuous theory refinement approach in order to link up specific stimulus properties with general personality functioning.

The Taxonomy Of Personality

At present, the Eysenckian model still has three – and only three – super-factors: Psychoticism, Extraversion, and Neuroticism (known as P-E-N). Eysenck was quite convinced that these three conceptual and descriptive categories are necessary and sufficient for a thorough understanding of individual differences in personality.

Extraversion is perhaps the best known of the three Eysenckian dimensions and is at the very “heart” of the model. Eysenck’s cortical arousal theory of Extraversion has been extensively described in numerous books (e.g., Eysenck 1973), book chapters, and articles. Revelle (1997) succinctly summarized the classic Eysenckian hypothesis of arousal underpinning his Extraversion factor. “The basic assumptions were: (1) introverts are more aroused than extraverts; (2) stimulation increases arousal; (3) arousal related to performance is curvilinear; (4) the optimal level of arousal for a task is negatively related to task difficulty; and (5) arousal related to hedonic tone is curvilinear. Assumption 1 was based upon many studies associating EPI-E with (low) physiological arousal Eysenck (1967). Assumptions 3 and 4 were based upon the Yerkes-Dodson Law (Yerkes and Dodson 1908) and the subsequent support for it by Broadhurst (1959). Assumption 5 was founded on Berlyne’s (1960) discussion of curiosity and arousal. Based upon assumptions 1–4, it can be predicted that introverts should perform better than extraverts under low levels of stimulation but should perform less well at high levels of stimulation. Similarly, assumptions 1, 2, and 5 lead to the prediction that extraverts should seek out more stimulation than introverts” (p. 199).

Neuroticism is based on activation thresholds in the sympathetic nervous system or visceral brain. This is the part of the brain that is responsible for the fight-or-flight response in the face of danger. Neurotic persons have a low activation threshold: when confronted with even mild stressors or anxiety-inducing situations, they quickly and easily experience negative affect and become upset. These manifestations can range from physiological changes in heart rate, blood pressure, cold hands, sweating, and muscular tension to feelings of apprehension and nervousness, to the full effects of fear and anxiety. In contrast to Neuroticism (or emotionally unstable and labile persons), their emotionally stable peers have a much higher activation threshold, and thus will experience negative affect only when confronted by major stressors. Such individuals tend to be calm even in situations that could be described as anxiety inducing or pressure laden. A full description of neurosis is provided by Eysenck in his 1977 book “You and Neurosis.”

Eysenck’s Personality Theory, Fig. 1 Causal pathways in Eysenck’s theory

Eysenck’s Personality Theory, Fig. 1 Causal pathways in Eysenck’s theory

Psychoticism, the most underdeveloped and debated of Eysenck’s three super-factors, was most fully described by Eysenck and Eysenck (1976) in the book “Psychoticism as a Dimension of Personality.” High P scorers are predisposed to psychotic episodes but also tend to manifest a higher probability of engaging in aggression and demonstrating the kind of cold tough-mindedness that characterizes psychopathy and persons more likely to engage in crime (Eysenck 1977). While somewhat less fully described and with less empirical support than either E or N, the research that has been done has indicated that P also has a biological basis. The P factor is particularly relevant to crime and criminology. Indeed, the fact that criminals are overwhelmingly male was one of the key observations that Eysenck made in order to hypothesize that the biological basis of P may be related to androgens (e.g., increased testosterone levels).

The past 20 years has witnessed a protracted debate between pro-Eysenckians, who support various permutations of the Giant Three Eysenckian system, and those who support the various Big Five models. The two positions were clearly debated between proponents in conferences and journal articles. For those who were so fortunate to witness the debates between Eysenck and Costa, and others such as Goldberg (e.g., at the ISSID conference in Oxford University in 1991), these were truly akin to the “clash of the Titans.” While the debate was always intense, each “proponent” bringing out more data to support their position, it was always respectful of each person’s work and commitment as a scientist.

Costa and McCrae (1992) summarized the evidence for the validity of the five-factor model by stating the “four ways the five factors are basic.” These were, first, that longitudinal and cross-sectional studies have shown five robust factors to underlie enduring behavioral dispositions; second, that traits associated with the five factors emerge from different personality data sources (self-reports versus other reports) as well as from studies of natural language (i.e., lexicon) conducted in many different countries; third, that the five factors are found in different age, sex, and ethnic groups; and fourth, that their heritabilities point to some underlying biological basis. Subsequently, further evidence demonstrated cross-cultural similarities and stabilities in the developmental and ageing trajectories of the five factors (Furnham et al. 2008).

Eysenck (1992) rigorously criticized fivefactor models of personality. He suggested that the criteria set out by Costa and McCrae for accepting the five-factor model (some of which Eysenck had himself proposed and pioneered, such as heritability studies of personality) are necessary, but not sufficient for determining the essential dimensions of personality. He argued that Agreeableness and Conscientiousness are lower-level traits that can be conceptualized as facets of his higher-order factor Psychoticism. Additionally, he contended that Openness forms a part of Extraversion and (low) Conscientiousness a part of Neuroticism. Thus, O, A, and C were lower order, not super-factors. Incidentally, a new line of research focusing on the possibility of a General Factor of Personality has received its most emphatic support from robust intercorrelations between the supposedly orthogonal Big Five factors (Rushton et al. 2009).

Eysenck also pointed out the meta-analysis of factor analytic studies of personality, carried out by Royce and Powell (1983), which indicated a three-factor model similar to his own. Eysenck suggested that the five-factor model lacks a theoretical basis sufficiently grounded in empirical facts and is, therefore, arbitrary. He explicitly juxtaposed this arbitrariness against his conceptualizations of Neuroticism and Psychoticism, which were firmly rooted in mental health and clinical psychology research.

Eysenck (1992) argued that it is the nomological network in which a dimension is embedded that corroborates its validity. This network must include a detailed specification of a personality dimension’s biological and psychophysiological origins, its cultural invariance, and its relationship to social behavior and psychological illness. Indeed, one of Eysenck’s most significant contributions to personality research was his shifting of the field’s agenda, from nebulous Freudian speculation to rigorous biopsychological integration (Eysenck 1967).

Eysenckian Measures

Eysenck devised and validated numerous inventories that are still widely in use. Furnham et al. (2008) suggested five reasons why these measures have stood the test of time:

(A) Parsimony. The P-E-N model offers a firstclass conceptual foundation for the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQ), which is one of the most parsimonious and psychometrically robust personality inventories. It compares favorably with the 16 dimensions of Cattell’s 16PF or the Big Five, Six, or Seven (there have been several attempts to expand Big Five models by adding allegedly new traits). In some ways, focusing on second-order factors is akin to the role of “g” in the measurement of intelligence. While some psychologists have argued through the bandwidth-fidelity debate for finer grain analysis at the facet (primary and lower-order) factor level, to some extent the Eysencks resisted this trend although the creation of measures such as the I6 and I7 did provide an assessment of several key variables including venturesomeness, impulsivity, and empathy. Recently, there has been a focus on primary factors and their acolytes started working with the EPP. More recently there has been considerable interest in the EPP and the facet/primary factor level of analysis (Jackson et al. 2000). While the Eysencks always measured super-factors or traits (i.e., the Gigantic Three), some researchers have argued that a finer-grained level of analysis (i.e., facet level) enables one to understand the nature of processes better (Petrides et al. 2003).

(B) Explanation of Process. More than any other test developers in the twentieth century, the Eysencks were not content to just describe and categorize traits: they constantly sought to escape tautological explanations. Eysenck’s was the first counterintuitive theory of arousal to explain individual differences in Extraversion. Hans Eysenck showed, nearly a decade before the publication of the EPQ (Eysenck 1947), that his work and interests were solidly grounded in the biological basis of personality, which he set about exploring for the next 30 years (Eysenck 1967, 1982b). More than any other personality theorist, he was concerned with describing and explaining the mechanisms and processes which account for systematic individual differences. Eysenck’s theory and model of individual differences is fully described in an earlier chapter by O’Connor and will not be repeated here; only a thumbnail sketch will be provided to provide the context for the development of the various personality measures developed by both Hans and Sybil Eysenck and colleagues.

(C) Experimentation: Eysenck was rigorously schooled in the experimental tradition at a time when behaviorism and psychoanalysis triumphed. He believed it essential that the correlational (individual differences) and experimental branches of psychology unite, so that personality effects will cease to be treated as error variance (Howarth and Eysenck 1968). This basic premise was the foundational underpinning for the creation of both the International Society for the Study of Individual Differences (ISSID) and also the Society’s official journal, Personality and Individual Differences, arguably the leading journal in the field.

(D) Wide Application. The Eysencks were psychological pioneers as well as risk takers; they were eager to extend their research program to look at the significance of personality functioning in areas as disparate as sex, crime, parapsychology, astrology health, and behavioral genetics among many others. They were convinced that individual differences were systematically and predictably present in all facets of human functioning. To many, particularly those favoring sociological or more exclusively environmental perspectives (e.g., based on parenting styles or early childhood experiences), this was radical indeed.

(E) Continuous Improvement and Development. For nearly 40 years the Eysencks have engaged in a systematic research program aiming to improve, update, and validate their range of personality measures. Because their scales have been so widely used in research worldwide, they have been subject to detailed but, at times, ungenerous scrutiny by many people. Their observations and research studies, particularly those emphasizing a cross-cultural perspective, led to continuous improvements over time, with items being removed, changed, and replaced. Importantly, all of this psychometric development was guided not by commercial opportunities, but firmly by theoretical considerations and empirical evidence.

Personality Structure Cross-Culturally

Most personality theorists hypothesize that major individual differences variables, such as intelligence and personality, are universal constructs. While they may vary in their expression (phenotype) as a function of culture and other psychosocial factors, basic traits are common across humankind. Some psychologists would also argue that the measurement of their specifically described traits or constructs would be universal across all countries and cultures. Considerable research has been published over the years demonstrating the significant contribution that genetic, biological, neurological, and environmental factors make in shaping the expression of intelligence and personality.

For over 20 years, Sybil Eysenck published research comparing the results of studies on adults and children using the adult and junior versions of the EPQ. In 1981, the Eysencks summarized the results of 14 countries based on just under 15,000 subjects (Eysenck and Eysenck 1981). In 1985, they extended their analysis to 24 countries and in 1998 this was further extended to 34 countries (Barrett et al. 1998). As each national group was added, so inevitably the population sample increased, but more impressively so did the quality of the statistical analysis. Sybil Eysenck also published a dedicated book detailing specific studies of the Eysenck scales used in different countries with children and adolescents.

Personality and Crime

Perhaps the most robust and fecund of the theories of the criminal personality is that of Eysenck (1977). Feldman (1993) has noted: “One of the theory’s great merits is that it makes predictions which are clear cut, testable and refutable” (p. 166).

The idea is beguilingly simple. Eysenck believed that sociological theory has little to offer society on the causes of crime, arguing that psychological theories have more explanatory power (Eysenck and Gudjonsson 1989). Criminal behavior is not the product of either environment or biology alone, but rather of a dynamic interaction between the two. This extends Eysenck’s original hypothesis that biology played the largest part in determining criminality, expounded in his book “Crime and Personality” (Eysenck 1964). Eysenck suggested that some people are born with cortical and autonomic nervous systems that compromise their ability to learn from their environment and renders them susceptible to illegal and criminal acts.

Each of the three Eysenckian factors relates to some aspect of conditionability, notably the learning of rules of society.

Extraverts are social and impulsive. They are excitement seekers interested in novel experiences, which often leads them to be poorer learners than introverts at many tasks, including the acquisition of general social rules. They are somewhat more likely than introverts to become delinquents or criminals.

Neurotics are anxious, moody, restless, and rigid. They react strongly to threat often with great fear to painful stimulation. This means they too do not learn social rules well and are “inefficient learners” particularly with respect to punishment.

Psychotic (tough-minded) individuals tend to be aggressive, egocentric, insensitive, inhumane, uncaring, and troublesome, and they are far more likely than their tender-minded peers to engage in delinquent and criminal behavior.

Those who score high on the P-E-N end of the Eysenckian dimensions tend to be least socially conditioned and, hence, least socially restrained. They are aggressive, hedonistic, impulsive, and reckless. The Eysenckian view links personality and criminality with a simple mechanism: personality traits are linked to learning proand antisocial behaviors that are linked to delinquent and criminal behavior and recidivism.

Eysenck and Gudjonsson (1989) in summary note as follows:

- There exists a general behavior pattern of antisocial behavior and criminality, marking the opposite end of a continuum that has prosocial and altruistic behavior at its other end.

- Within the antisocial and criminal type of behavior, there is a certain amount of heterogeneity, marked particularly by the opposition between active and inadequate criminals (UNCLEAR), but probably also including differences according to type of crime committed.

- Criminality is related to certain dimensions of personality, most especially Psychoticism, which is apparent across all age groups and conditions studied.

- Extraversion is also linked to criminality, particularly in younger samples and among more active criminals; inadequate older criminals do not show high extraversion and may indeed be below average on this trait.

- Most criminals are characterized by a high degree of Neuroticism, but this may not be found as markedly in children and youngsters.

- Scores on the social desirability (L) scale are regarded in these studies as a measure of conformity (rather than of dissimulation) and tend to correlate negatively with antisocial and criminal conduct, in children, adolescents, and adults.

- The criminality scale, made up of the most diagnostic items of the EPQ, discriminates reliably between criminals and noncriminals.

- Primary personality traits, such as impulsiveness, venturesomeness, risk taking, and empathy correlate, in predictable directions, with antisocial and criminal conduct.

- These relationships are observed also in research where self-reports of antisocial behavior are the criterion of interest. Thus, personality-criminality correlations are not confined to legal definitions of crime or to samples of incarcerated criminals.

- The personality-criminality correlations have cross-cultural validity, appearing in different countries and cultures with equal prominence.

- Personality traits characteristic of antisocial and criminal behavior also correlate with behavior that is not criminal per se, but is regarded as antisocial – whether legal or illegal (e.g., smoking and drug use, respectively). Studies show high P and N scores among drug users, although E scores are elevated only among drug users who have also been convicted of other crimes.

Eysenck and Gudjonsson (1989) concluded that “.. .psychological factors and individual differences related to the personality are of central importance in relation to both the causes of crime and its control. This does not mean to say that other factors, such as sociological and economic ones, are not important. Indeed, in many instances they are. We believe that sociological theories are particularly relevant in relation to victimless crimes and less so in the case of victimful crimes.

Psychological factors in criminality, we argue, relate to genetic and constitutional causes and to personality and other sources of individual differences. This does not mean that some people are destined to commit crimes. Criminal behavior as such is not innate. What is inherited are certain peculiarities of the brain and nervous system that interact with certain environmental factors and thereby increase the likelihood that a given person will act in a particular antisocial manner in a given situation.” (p. 247)

There are, of course, considered and extensive critiques of the Eysenckian approach to the understanding of criminals and crime frequently revolving around the points below:

- Self-report measures of both crime/delinquency as well as of personality are open to dissimulation, lying, denial, exaggeration, etc. In addition, their interrelationships may appear inflated in research investigations due to common method variance.

- Caught criminals are unrepresentative of the population. Most criminals are, alas, not caught.

- Criminals and delinquents are far from homogeneous (e.g., murderers are very different psychologically from con men).

- Incarceration may affect personality, notably increase Neuroticism and reduce Extraversion. Prisoners may change as a function of their imprisonment and, thus, there may be reciprocal links between personality traits and crime-related variables.

- Being nonexperimental in nature, personality research is unable to demonstrate unequivocal causal relationships between personality traits and outcomes of interest.

- Trait personality theories tend to underemphasize social and environmental factors, although recent advances in the field of multivariate statistics have allowed for more realistic conceptualizations combining all of these influences and countering objections by sociologists and educationalists.

Eysenck’s position developed and changed over time. He gradually placed more emphasis on the role of Psychoticism and began to admit more freely the range of the social causes of crime. Nevertheless, he continued advocating a central role for personality traits, a position that has consistently received support over the years including from rigorous longitudinal (birth-cohort) studies. Thus, Caspi et al. (1994) and Wright et al. (1999) found replications in the Eysenkian hypothesized personality – crime relationships across country, gender, race, and method. As suggested by the theory, poor social control (impulsivity, hyperactivity, etc.) predicted weak social bonds, adolescent delinquency, and later criminality. In a large meta-analytic review, Miller and Lynam (2001) found that personality traits relate to antisocial behavior, in general, and to crime, in particular, in both distal and proximal ways. Thus, personality predicts how people react to situations, how other people react to them, and indeed the situations they find themselves in. Miller and Lynam concluded that individual differences variables can help account for the observed stability of antisocial behavior over the life-span.

Conclusion

It is perhaps still true that no psychologist before or after Hans Eysenck attempted to show and explain how personality variables relate to such a wide array of everyday social behaviors from aesthetic appreciation to sport and school success to sport. Among his interests was how personality, in terms of his Giant Three system, related to all aspects of crime. His first book, published nearly 50 years ago, set out a bold and clear theory linking personality to various aspects of crime. The book has been quoted over 1,200 times. It provoked criticism but galvanized differential psychologists into testing the theory. Both updates and reviews constantly appear (Blonigen 2010; Levine and Jackson 2004). To some extent the early work rather overemphasized the role of personality variables in crime, probably in reaction to a domination of sociological and psychological theories of crime. His second book, coauthored with Gudjonsson – a clinical and forensic psychologist – was a more measured and better-referenced book on the topic.

Clearly personality variables must and do play a part in all aspects of criminal behavior. The question is how much of the variance they do explain apart from other demographic and social environmental factors.

Bibliography:

- Barrett PT, Petrides KV, Eysenck SBG, Eysenck HJ (1998) The eysenck personality questionnaire: an examination of the factorial similarity of P, E, N, and L across 34 countries. Personal Individ Differ 25:805–819

- Berlyne DE (1960) Conflict, arousal and curiosity. McGraw Hill, New York

- Blonigen D (2010) Explaining the relationship between age and crime: contributions from the developmental literature on personality. Clin Psychol Rev 30:89–100

- Broadhurst P (1959) The interaction of task difficulty and motivation: the Yerkes-Dodson law revived. Acta Psychol 16:321–328

- Caspi A, Moffit T, Sliva P, Kreuger A et al (1994) Are some people crime prone? Criminology 32:163–195

- Costa PT Jr, McCrae RR (1992) Four ways five factors are basic. Personal Individ Differ 13:653–665

- Eysenck HJ (1967) The biological basis of personality. CC Thomas, Springfield, Reissued in 2006 by New York: Transaction Publishers

- Eysenck HJ (1947) Dimensions of personality. Praeger, New York, Reissued in 1998 by New York: Transaction Publishers

- Eysenck HJ (1964/1977) Crime and personality. Routledge and Kegan Paul, London

- Eysenck HJ (1973) Historical introduction. In: Eysenck HJ (ed) Eysenck on extraversion. Wiley, London, pp 3–16

- Eysenck HJ (1977) You and neurosis. Maurice Temple Smith, London

- Eysenck HJ (1982) Personality, genetics and behaviour. Praeger, New York

- Eysenck HJ (1992) Four ways five factors are not basic. Personal Individ Differ 13:667–673

- Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG (1976) Psychoticism as a dimension of personality. Hodder and Stoughton, London

- Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG (1981) Culture and personality abnormalities. In: Al-Issa I (ed) Culture and psychopathology. University Park Press, Maryland

- Eysenck HJ, Gudjonsson GH (1989) The causes and cures of criminality. Plenum Press, New York

- Feldman P (1993) The psychology of crime. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

- Furnham A, Thompson J (1991) Personality self-reported delinquency. Personal Individ Differ 12:585–593

- Furnham A, Eysenck H, Saklofske D (2008) The eysenck personality measures: fifty years of scale development. In: Boyle G, Matthrews G, Saklofske D (eds) Handbook of personality testing. Sage, California, pp 199–218

- Howarth E, Eysenck HJ (1968) Extraversion, arousal, and paired associate recall. J Exp Res Personal 3:114–116

- Jackson CJ, Furnham A, Forde L, Cotter T (2000) The structure of the eysenck personality profiler. Br J Psychol 91:223–239

- Levine SZ, Jackson CJ (2004) Eysenck’s theory of crime revisited. Leg Criminol Psychol 9:135–152

- Miller J, Lynam D (2001) Structural models of personality and their relation to antisocial behaviour. Criminology 29:765–798

- Netter (2007) Modern research on the neurochemical basis of individual differences rooted in Hans Eysenck’s theory. Paper at the ISSID conference, July

- Petrides KV, Jackson C, Furnham A, Levine S (2003) Exploring issues of personality measurement and structure through the development of a short form of the eysenck profiler. J Personal Assess 81:271–280

- Revelle W (1997) Extraversion and impulsivity: the lost dimension? In: Nyborg H (ed) The scientific study of human nature: tribute to Hans J. Eysenck at eighty. Pergamon, New York, pp 189–212

- Royce JR, Powell A (1983) Theory of personality and individual differences: factors, systems and processes. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs

- Rushton JP, Bons TA, Hoor Y-M, Ando J, Irwin P, Vernon PA, Petrides KV, Barbaranelli C (2009) A general factor of personality from cross national twins and multi-trait multimethod data. Twin Res Hum Genet 12:356–365

- Wright B, Caspi A, Moffitt T, Silva P (1999) Low self-control, social bonds and crime. Criminology 37:479–513

- Yerkes RM, Dodson JR (1908) The relative strength of stimuli to rapidity of habit information. J Comp Neurol Psychol 18:459–482

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.