This sample Geography of Crime and Disorder Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

The study of the geography of crime has a long history, stretching back to the early nineteenth century. After a quiescent period in the middle of the twentieth century, it has now again become a field of strong research activity. However, the interests of scholars in this field have often been divergent: for example, some have been motivated by very practical (crimepreventive) concerns, while others are more interested in explanatory theory; some have mainly focused on neighborhoods, but others see greater merit in studying micro-locations. Not infrequently, work in these different traditions has been pursued in relative isolation, leading to some fragmentation of the field. However, there is now a growing interest in developing a more integrated understanding of geographical criminology (Bottoms 2012; Weisburd et al. 2012; Wikstro¨ m et al. 2012). This research paper is written from that integrative perspective, with a special focus on arguably the three most important strands of research in the recent geography of crime, namely, the “hotspots approach,” the “neighborhood effects tradition,” and the “signal crimes perspective.” The chapter is organized into three main sections, focusing respectively on space, social structure, and social action.

Three Research Approaches In The Contemporary Geography Of Crime

The “hotspots” approach within criminology effectively began with a seminal paper by Sherman et al. (1989), which showed that 50 % of the crime-related calls made to the police in Minneapolis related to just 3.3 % of the micro-locations in the city. This degree of concentration of crime seemed to offer significant potential for targeted crime prevention programs, and such programs have subsequently been successfully developed by scholars and practitioners working in the hotspots tradition (Braga and Weisburd 2010; Weisburd et al. 2010). Indeed, it has been recently argued that “the police can be more effective if they shift the primary concerns of policing from people to places” (Weisburd et al. 2010, p. 7).

The “neighborhood effects tradition” is older and can be traced back to the work of the Chicago School of Sociology in the 1930s. The argument of the Chicagoans was that “socially disorganized neighborhoods” produced more juvenile delinquents than other residential areas with similar populations; in other words, that aspects of the social structures and the culture of certain neighborhoods could lead to the development of criminality in some individuals who would otherwise have remained crime-free. For a time, the existence of such “neighborhood effects” (as opposed to “individual effects” or “family effects”) was challenged, but in light of further research evidence, they can now be regarded as clearly established (for a review see Bottoms 2012). For example, in a paper based on data from the Pittsburgh Youth Study, Wikstro¨ m and Loeber (2000) showed that, after controlling for various individual “risk factors” for offending (such as impulsivity, poor parental supervision, and low school motivation), neighborhood factors remained causally important in generating adolescent criminality, at least in the poorest neighborhoods.

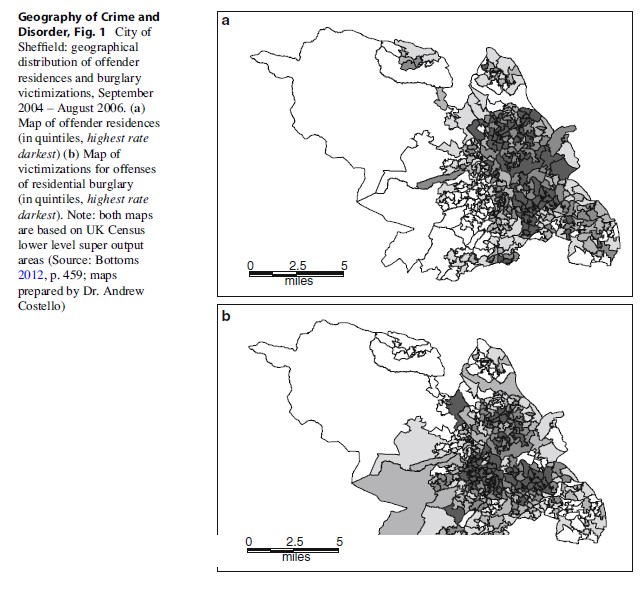

There are two important differences of empirical focus as between the hotspots approach and the neighborhood effects tradition. First, as their names imply, there is a difference in geographical scale: hotspots are micro-locational, while the study of neighborhoods entails a locationally wider research focus. Secondly, the dependent variable for hotspots researchers is the criminal event located in geographical space, while the neighborhood effects tradition, being concerned with potential neighborhood influences on the criminality of individuals, focuses particularly on the geographical location of offenders’ homes. Yet despite these differences, in real-life research contexts the two approaches are empirically interconnected, because one of the bestestablished and durable findings in the geography of crime is that – for reasons to be discussed later – many offenses are committed close to offenders’ homes. This is illustrated in Fig. 1 which displays data on the location of offender residences and of recorded residential burglary victimizations in Sheffield, England, a city with a population of half a million. Sheffield is well known as a “city of two halves,” with the population of the eastern half being substantially poorer, and having a lower life expectancy, than those living in the western half. Figure 1a shows that offender residences are very disproportionately concentrated in eastern Sheffield. One might therefore suppose that many offenders intending to burgle might travel the short distance from east to west Sheffield to take advantage of the (on average) much more lucrative theft opportunities available in the houses in the west. However, although there is clearly some movement in this direction (see Fig. 1b), most of the areas with high victimization rates for residential burglary are, as with offenders’ residences, found in the east. Given data of this kind, it is now well established that an important risk factor for a high area victimization rate is that the location lies close to an area of high offender residence. That simple fact is one of the most important reasons why a better integration of research from the “hotspots” and “neighborhood effects” traditions is desirable.

The third strand of research, “the signal crimes perspective,” is the most recent. It draws in part from the field of study known as semiotics (“the science of signs and symbols”), which focuses especially on the operation of such symbols in communication. Semiotics is relevant to geographical criminology because the signs emitted at particular locations can send messages that significantly affect behavior; for example, research in the Netherlands has shown that signs of disorder in public places (such as uncleared litter) tend to encourage further breaches of norms (including theft), while norm-compliant behavior (e.g., someone sweeping up litter) can encourage other norm-compliant behavior (e.g., helping a stranger who has dropped fruit in the street) (Keizer et al. 2008; Keizer 2010). According to Martin Innes, the originator of the signal crimes perspective (SgCP), criminology lacks “a coherent explanation of the public understanding of crime and disorder and how such understandings are imbricated in the wider symbolic construction of social space.” Substantively, SgCP proposes that “some crime and disorder incidents matter more than others to people in terms of shaping their risk perceptions” in visiting defined locations (Innes 2004, p. 336, emphasis added). Thus, for example, three spouse murders in a month in a medium-sized town would be very unusual, but would not necessarily create widespread fear, or a sense of threat, in the community at large, because they would be seen as “private matters.” By contrast, the abduction and murder of a local schoolgirl on her way to school would almost certainly generate much more fear, and a sense of threat, in the area, because of the signal it would transmit about potential risks in the community. In light of this signal, ordinary people might freshly consider as “risky” certain places, people, or situations that they might encounter in their everyday lives; hence signals are seen in SgCP as social-semiotic processes by which particular crimes and disorders might have a disproportionate effect in terms of fear and perceived threat, often in relation to specific locations. It will accordingly be noted that the focus of this third theoretical approach is – by contrast with the first two approaches – on neither area crime rates nor area offender rates as such, but rather on the symbolic meanings that people might attach to specific locations as a result of certain acts occurring in or near them or the characteristics of people believed to be present in the location.

From the above account, it will be clear that the three research traditions described, while distinct from one another, are in no sense necessarily contradictory. Coherent synthesis of the approaches, within defined contexts, is therefore in principle certainly possible, and aspects of this complementarity will hopefully become more evident in the ensuing sections of this research paper. In these sections, research results on the geography of crime and disorder will be considered within the framework of the three core dimensions of research in human geography: space, social structure, and social action.

Space

Human beings exist only within physical bodies. Although, in the Internet age, an increasing number of activities can be undertaken in virtual space, physicality remains important for many human activities, notably travel and the use of public space. This first section therefore considers physical places and spaces and their relevance within geographical criminology.

The physicality of humans is, however, not their only characteristic. Uniquely within the animal kingdom, humans possess the gift of language, and the ability to be self-reflexive about the situations in which they find themselves. In considering humans’ use of space, therefore, it is necessary to address perceptions of locations, as well as the physical context. Within this dual framework, three topics will be discussed, namely, crime opportunities, hotspots, and the meaning of space.

Crime Opportunities

It is now well established in psychological research that much behavior is situation specific, and that people often act differently if some aspect of a particular type of situation is altered. A striking demonstration of these points was provided by Ronald Clarke and Pat Mayhew (1988), who showed that the suicide rate had dropped suddenly in Britain in the 1970s when the source of domestic gas supplies was switched from coal gas (toxic) to natural gas from the North Sea (nontoxic) and that there was no plausible explanation of this decline other than the change in the nature of the gas supply. In other words, even people desperate enough to try to end their own lives often did not turn to alternative methods when the immediate situational context was altered. Given this and other similar evidence, Ronald Clarke and others have made a special study of the specific situations in which different offenses are committed, with a view to modifying those situations to produce a reduction in crime – an approach known as situational crime prevention (StCP). Typically, this might involve strategies such as making goods harder to steal by strengthening security at potential targets, reducing the availability of the means to commit certain crimes (e.g., by restricting sales of guns or knives), or environmental management (e.g., separating the fans of opposing teams at football matches). Such strategies have often led to beneficial results, and there are now many reports of successful StCP initiatives (Felson and Boba 2010: ch. 10). Some of these initiatives are explicitly locational, and a good example is the strategy known as “alley-gating.” In working class residential areas in British industrial cities, a favored style of pre-Second World War housebuilding was “back-to-back terraces,” that is, rows of terraced houses opening directly on to the street, with small yards or gardens at the rear, backing on to an identical set of terraces in the next street. Normally, a “back alley” is located between the yards/gardens of the two rows of houses. Crime analysts noticed that the entry point for house burglaries in such areas was very often from the rear, and this led to the prevention strategy of “gating” the entrances to the back alleys. Evaluations of such initiatives have shown them to be successful in reducing burglary; moreover – and congruently with the evidence from the gas suicide example – there was no evidence of displacement of burglaries to nearby residential areas (Bowers et al. 2004).

Closely related to the StCP approach is routine activities theory (RAT), whose central proposition is that “the probability that a [criminal] violation will occur at any specific time and place might be taken as a function of the convergence of likely offenders and suitable targets in the absence of capable guardians” (Cohen and Felson 1979, p. 590; see also Felson and Boba 2010). This approach, which incorporates a specifically spatial dimension (see the italicized phrase), usefully divides the concept of “opportunity” into two component parts (“targets” and “guardianship”), but more importantly, it draws attention to the fact that the routine activities of a population can – often unwittingly – create or restrict criminal opportunities in defined locations. To take an example from a British study, multistory parking lots at train stations used by commuters (where few owners visit the lot during the working day) were shown to have a higher victimization rate than similar parking lots attached to shopping malls (where shoppers are leaving and returning to their vehicles all day, providing a flow of natural surveillance or guardianship). Many examples of a similar kind are provided by Felson and Boba (2010); as they memorably phrase the matter, these examples show how “noncriminal realities give rise to criminal events” (p. 205).

It is therefore a serious mistake to see criminal opportunities as existing in a social vacuum. This point is further illustrated through Patricia and Paul Brantingham’s seminal contribution to geographical criminology, first formulated 30 years ago (Brantingham and Brantingham 1981), andnow incorporated within a broader crime pattern theory (Brantingham and Brantingham 2008). These authors postulated that most offenders, like most people, feel much more comfortable in areas that they know reasonably well; in consequence, even when – for example – potential burglars are engaging in a search pattern for a suitable target, it is hypothesized that they will usually not wish to venture into residential areas that are completely unknown to them. In other words, the suggestion is that offenders will usually commit crimes in areas already known to them through their routine activities. (Oddly, routine activities theorists until recently paid little attention to this point, being more interested in how targets and guardianship are influenced by routine activities.) Subsequent empirical research evidence has strongly supported the Brantinghams’ hypothesis (see especially Wikstro¨ m et al. 2012: ch. 7), and this body of work clearly helps to explain why many offenses are committed not far from offenders’ homes (see above), as well as in other locations in which they regularly spend time, and where there are criminal opportunities (such as downtown areas and leisure outlets). These social realities therefore illustrate the point that a so-called opportunity for crime in a given area is, in the full sense, only an opportunity when it is perceived as such by someone who (i) might enter the area and (ii) is willing to consider turning the opportunity into an act of crime. Otherwise identical physical “opportunities,” if located in different social contexts, might differ greatly in the number of passersby who would consider committing a crime at the micro-location, and such differences will almost certainly be reflected in their aggregate victimization levels.

Sometimes, even more complex narratives emanate from discussions of “opportunities for crime”; street lighting is an important example. Improved street lighting was originally advocated as a situational crime prevention strategy in the belief that better lighting would increase the number of people using the location at night (thus providing improved guardianship of the area) and would also make potential offenders more visible (thus making them more easily detectable if they committed a crime). Both these effects were thought likely to deter potential offenders from committing crimes in the relevant area, because the opportunities for successful lawbreaking had been reduced. However, the actual research evidence is more complex. A Campbell Collaboration review of relevant empirical studies has concluded that, while “improved street lighting significantly reduces crime,” it was also the case that, in areas with improved lighting, “night-time crimes did not decrease more than daytime crimes” (Welsh and Farrington 2008, p. 2). This finding presents problems for a simple opportunity theory, because if enhanced deterrence were the only mechanism in play, one would expect crime reductions in better-lit areas during hours of darkness, but no difference in crime rates during daylight hours. Accordingly, the Campbell reviewers concluded that the daytime effect was possibly occurring because “improved lighting signals community investment in the area and that the area is improving, leading to increased community pride, community cohesiveness and informal social control.” This interpretation therefore seems to embrace not only “opportunities” but also the more normative language of the signal crimes perspective (note the word “signal” in the sentence quoted above, although the SgCP approach is not explicitly mentioned by the reviewers). However, the temporal sequencing of possible “deterrent” and “signal” effects has been insufficiently studied, so – as the authors make clear – further research is needed. But the juxtaposition of the two approaches in the Campbell Review is of great interest.

Hotspots

Like those who have focused on crime opportunities, criminologists who have developed the “hotspots approach” have concentrated on micro-locations. Indeed, they have very usefully shown that the neighborhood level of analysis can be misleading in the geographical study of crime events, because – for example – what might seem overall to be a “crime-prone neighborhood” often contains micro-locations with very varied levels of crime, including some low-crime locations. These findings have led to a justifiable emphasis on the desirability of using small units of analysis when studying crime events (Weisburd et al. 2009). Accordingly, in a major recent research study in Seattle, to be described later, Weisburd and colleagues (2012) adopted as their unit of analysis the “street segment,” that is, both sides of a street between two intersections in a standard North American street grid.

A main motivating reason for the development of the hotspots approach has been crime prevention. However, before researchers could confidently recommend to policymakers a preventive strategy based on hotspots, several issues beyond the simple demonstration of crime concentrations needed to be explored. These included the following:

(i) Perhaps the identified hotspots were ephemeral, so that a different set of hotspots would appear if one were to conduct the analysis for a later year or a series of years.

(ii) Perhaps crime prevention initiatives targeted on specific places would not actually reduce crime at the hotspot.

(iii) Even if the crime prevention effort was successful at the hotspot, perhaps those committing crimes in that location would simply move their activities elsewhere (“crime displacement”).

These were reasonable questions, but subsequent research has convincingly dispelled doubts. Briefly, longitudinal analyses have now shown that hotspots in given cities are usually enduring, not ephemeral; rigorous evaluative studies have demonstrated that “hotspot policing” crime prevention strategies can be effective; and displacement is rarely a problem (Braga and Weisburd 2010; Weisburd et al. 2010). This body of work constitutes an impressive contribution to scholarship by hotspots researchers. But in addition – and of great interest to the quest for integration under discussion in this essay – hotspots researchers have begun to pursue the question of the legitimacy of crime prevention initiatives at crime hotspots. (On legitimacy and criminal justice, see Bottoms and Tankebe 2012). For example, Braga and Weisburd (2010: ch. 6) have set out in schematic form three different models by which police could in principle seek to control crime at hotspots: these are the “traditional” (or “reactive”) model, in which police respond to incidents as they occur; a proactive “strong enforcement” model (such as the widely discussed “zero tolerance” approach to policing); and a proactive “situational prevention” model, focusing crime prevention efforts on targeted micro-locations identified through prior crime analyses. The third of these is the authors’ preferred model, and a principal reason given for rejecting the “strong enforcement” model is its potential for legitimacy deficits: “overly aggressive and indiscriminate arrest-based strategies are more likely to generate community concern and poor [police-public] relations” (Braga and Weisburd 2010, p. 229). On this view, therefore, when assessing the policy-relevant features of specific locations, it is necessary to consider not only objective matters such as the concentration of crime events but also more normative and perceptual issues such as the way in which law enforcement agents are viewed in the locality (which will include the historical legacy of past law enforcement, still present in the memories of current residents). Such matters will, however, very often relate not simply to the hotspot itself, but to the wider socio-structural context in which it is set (e.g., a particular policing approach might have been adopted for a whole neighborhood, not simply a specific hotspot). In such circumstances, it becomes necessary to widen the spatial scale of the issues to be addressed when considering policy responses to crime in the hotspot.

Despite the unquestioned importance of the hotspots approach as a development within geographical criminology, early research in this field was subject to some criticism, particularly concerning two alleged omissions: first, that (apart from the discussion of legitimacy) hotspots researchers had paid little attention to hotspots from the potential offender’s point of view and, secondly, that they had largely failed to analyze a key explanatory question, namely, why do some micro-locations have high crime, while others do not? Fortunately, both of these omissions have been addressed in more recent research.

An important study of hotspots from the offender’s perspective was undertaken by Peter St. Jean (2007) in a socially very deprived highcrime neighborhood in Chicago. In qualitative interviews, the researcher elicited persistent offenders’ views about optimum micro-locations for drug dealing and robbery. A strong “opportunity” dimension to offenders’ locational preferences was shown, and the most favored street blocks for committing crimes were busy road intersections containing commercial premises such as grocery stores, liquor stores, and check-cashing outlets, all of which bring together “people who can be clandestine clients of drug dealers or easy targets for robbers” (p. 197). In more residential areas, however, a further “opportunity” variable seemed to be in play, namely, the vigilance or otherwise of residents, since “watchful neighbors.. .sometimes serve as effective constraints against neighborhood robberies” (p. 208).

The issue of watchful neighbors brings into focus the theory known as collective efficacy, particularly developed by Robert Sampson. “Collective efficacy” is defined as the institutional ability to achieve what a group or community collectively wishes to achieve; and in criminological research it has been principally utilized in research in small residential areas. It is normally measured with survey items that tap into two linked matters: first, the willingness of residents to intervene for the common good in certain defined situations (such as children spraypainting graffiti on a building) and, secondly, the existence or otherwise of conditions of cohesion and mutual trust among neighbors (on the assumption that one is unlikely to take action in a neighborhood context where the rules are unclear and residents mistrust one another). Various empirical studies have confirmed that, in many local contexts, there is evidence for the crime-reductive effectiveness of collective efficacy (Sampson 2006).

The second main omission in early hotspots research (i.e., why do particular micro-locations have high crime?) has been principally addressed through two major research studies using different methodologies, one in the USA and one in England.

The American research was a multivariate correlational study using a unique 16-year dataset for Seattle for the years 1989–2004 inclusive (Weisburd et al. 2012). As previously noted, the unit of analysis in this study was the microlocational “street segment.” Congruently with earlier research, the study found (i) a strong concentration of crime in “hotspots” (5–6 % of street segments each year accounted for c.50 % of crime incidents) and (ii) with some exceptions, a “tremendous stability of crime at street segments over a long period of time” (p. 56). Eight “trajectory [crime] patterns” were identified.

Four of these (comprising 84 % of street segments) were stable over time, ranging in level from “crime-free” to “chronic crime”; the remainder showed increasing (4 %) or decreasing (12 %) trajectories. A multivariate analysis was then undertaken, in an attempt to uncover the factors that would predict a particular trajectory pattern in any given street segment. A principal feature of this analysis was an assessment of the comparative explanatory strength of (i) variables measuring the “opportunity perspective” (roughly, the kind of variables utilized in StCP and RAT) and (ii) variables measuring the “social disorganization perspective” (roughly, variables traditionally used in “neighborhood effects” research). Principal findings in the Seattle research were (i) that both these sets of variables were important contributors to explaining differential crime trajectory patterns in street segments, (ii) that opportunity variables had greater explanatory power than social disorganization variables in predicting variations in crime between microlocations at any one point in time, and (iii) that social disorganization variables had greater explanatory power than opportunity variables in predicting changes in crime levels in microlocations over time.

The first author of the Seattle study (David Weisburd) has been one of the leading researchers within the “hotspots” tradition. It is therefore noteworthy that in this study he and his colleagues deliberately set out to “broaden and expand the [traditional] theoretical foundations of the criminology of place” (p. 13), particularly by including variables representing the “social disorganization” (or “neighborhood effects”) tradition – a tradition that, as they observe, had previously been “virtually ignored” by hotspots researchers (p. 43). Moreover, the results of the Seattle analyses strongly support the view that both “opportunity” and “neighborhood effects” dimensions need to be included within any full answer to the question “why are certain microlocations hotspots, and others not?”

The second piece of recent research that aims to explain “why hotspots are hotspots” is the Peterborough Adolescent Development Study (PADS+) (Wikstro¨ m et al. 2012). This study, which was conducted in the medium-sized city of Peterborough, England (pop. c. 165,000), differs in three main respects from the Seattle study: it uses a different methodology, it is significantly more theory-driven, and – because it reports data from the early stages of a longitudinal study of criminal careers – it is restricted to juveniles. Despite these differences, its results in no way conflict with the principal conclusions of the Seattle study.

PADS+ was conducted within the theoretical framework of Per-Olof Wikstro¨ m’s “Situational Action Theory” (SAT). SAT postulates that to understand how criminality arises, one needs to consider two matters: first, an individual’s propensity to commit crime (defined as consisting of both the person’s morality and his/her ability to exercise self-control) and, secondly, his/her exposure to situations of varying criminogenic potential (where criminogenic exposure is defined as “encounters with settings in which the (perceived) moral norms and their (perceived) levels of enforcement.. .encourage breaches of rules of conduct.. .in response to particular opportunities or frictions”: Wikstro¨ m et al. 2012, p. 17). The theory therefore envisages a possible interaction as between criminal propensity and environmental (geographical) conditions.

Two main types of “criminogenic exposure,” both with a strong locational component, were considered in the Peterborough study, namely, that a young person spent time “unsupervised with peers in an area with high public entertainment” or “unsupervised with peers in a residential area with poor collective efficacy.” Both of these conditions, for different reasons, provide increased opportunities for offending. Using a detailed interview-based “time budget” methodology, and measuring crime by self-reported offending on the days for which time budgets were compiled, the researchers found that, overall, a substantially greater number of crimes were committed when young people were in conditions of hypothesized criminogenic exposure than when they were not. For those with a “strong” criminal propensity, the difference in the rate of crime commission when “in” or “not in” a criminogenic environment was particularly marked (for both exposure conditions). On the other hand, those with a low crime propensity committed no crimes whether or not they were in criminogenic exposure conditions; for them, their strong anti-crime dispositions were able to override any temptations offered in criminogenic exposure conditions. Thus, the results show a genuine interaction effect as between the propensity of individuals and the environmental contexts of these locations.

Interestingly, the Peterborough results also showed that those with a high criminal propensity tended to spend more time in conditions of high criminogenic exposure than other young people. This finding therefore emphasizes – as the research of the Brantinghams had suggested in a different way many years before – the particular importance for the geography of crime of the routine activity patterns of those with a high criminal propensity.

The Symbolic Meanings Of Places

In developing the “signal crimes perspective” (see above), Martin Innes and his colleagues conducted detailed qualitative interviews in 16 neighborhoods in England and Wales, asking representative respondents what they would identify as the key potential threats to neighborhood safety in their area (described in the theory as signal crimes and signal disorders). Not surprisingly, there was a good deal of local variation in the perceived threats identified in different localities. Nevertheless, a striking and largely unexpected result (although see not dissimilar concerns raised by Wilson and Kelling 1982) was that various kinds of physical and social disorders, not all of which were criminal acts, featured particularly strongly as perceived threats in the public responses in all areas. (Examples of such disorders included youths hanging around in groups, drug detritus, litter/graffiti, vandalism, and public drinking.) Indeed, such items were, in almost all areas, perceived as a greater threat to the area than residential burglary. These results appeared to be mainly explicable by the fact that the listed disorders are events occurring in public space, often with a strongly repetitive dimension: such events therefore seemed to send a powerful message to residents that “my area is out of control.” As one respondent put it to Innes (2004, p. 348):

Yes, it is daft, it is almost daft, but graffiti is the thing that sort of bothers me more, because it is in my face every day. I mean obviously rape and murder are more horrendous crimes, but it is graffiti that I see.

Thus, even quite minor incivilities in public space can, especially if persistent, be perceived as significant threats to peaceable daily living. This evidence is consistent with more general social scientific research results showing that disruptions of people’s everyday routines can be perceived as significantly threatening to their sense of ontological security. Such results accordingly suggest that some earlier scholars in geographical criminology have neglected an important dimension of lived experience by focusing exclusively on crimes, rather than on both crimes and disorders.

Social Structure

The most important social-structural topic of relevance for geographical criminology is that of social disadvantage. In some countries, including the United States, this topic has a strongly ethnic dimension, but for reasons of space the discussion here will focus on disadvantage more generally.

A consistent finding in geographical criminology is that offenders’ residences are very disproportionately located in more socially disadvantaged areas of cities (see, e.g., Fig. 1a). Given that many offenses are committed close to offenders’ homes, it is also the case that socially disadvantaged residential areas usually have higher crime victimization rates than richer areas (see Fig. 1b), and, at least in England, national crime surveys also show that they have the highest rates of repeat disorders. These facts seem to most geographical criminologists to require a serious engagement with issues of social structure, although this view is not universally shared (see Felson and Boba 2010, p. 206, final sentence).

Of these various indicators, the resident offender rate normally shows the starkest contrast between rich and poor areas, and this raises the possible existence of a “neighborhood effect” on offending in such areas. In considering this issue, great care in interpretation is required, as may be seen from the recent meticulous research on juvenile delinquency in the Peterborough study (Wikstro¨ m et al. 2012). On the one hand, social disadvantage is not explicitly part of the explanatory model tested and affirmed in this research (see above: the model, based on Situational Action Theory, is focused on criminal propensity and criminogenic exposure). Moreover, by no means all of the young people with a high criminal propensity lived in deprived neighborhoods. Nevertheless, in this study the researchers found that “population social disadvantage was a particularly important predictor of the number of resident young offenders” in a given area and that “social disadvantage and its influence on the efficacy of key social institutions such as the family and the school are clearly implicated in the understanding of why some young people develop a stronger crime propensity” (Wikstro¨ m et al. 2012, p. 239). Clearly, some complex social dynamics lie behind these important results, and the authors intend that future analyses from the Peterborough study will explicate the issues more fully.

From results such as these (see also Wikstro¨ m and Loeber 2000), it seems a reasonable hypothesis that moving children and young people from very socially deprived areas to less deprived areas should reduce their criminality, as well as providing other benefits to their families. These matters were tested in a large-scale randomized controlled trial known as the “Moving to Opportunity” (MTO) experiment, which was conducted in five major cities in the United States (Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York). So far as juvenile criminality was concerned, the results were unexpectedly mixed – on the best available evidence, the hypothesis of reduced misbehavior was confirmed for girls/young women, but boys/young men moving to less disadvantaged areas appeared to become more delinquent (Kling et al. 2007; Briggs et al. 2010; Clampet-Lundquist et al. 2011). Possible reasons for this gender difference, and in particular the counterintuitive result for boys, are discussed at the end of this research paper.

In considering issues of social disadvantage, it should not be forgotten that patterns of both informal and formal social control can vary in areas of differing social status and that these are of potential criminological significance. This point was drawn starkly to criminologists’ attention in the path breaking book by Lawrence Sherman (1992) analyzing the results of a series of experiments on police responses to domestic violence. In these randomized controlled trials, six American police departments responded to nonlife-threatening domestic violence incidents (where the assailant was still at the home) either by arresting the suspect or by some measure short of arrest. The results were more complex than had been anticipated. In summary, Sherman characterized three cities (Minneapolis, Colorado Springs, and Miami) as having shown a deterrent effect following arrest, while in three other cities (Omaha, Charlotte, Milwaukee) arrest appeared to have produced what was called a “backfiring effect” – that is, it seemed to increase subsequent violence among arrested suspects, by comparison with controls. This pattern of results naturally raised the question: “what.. .factors might explain the differences between the deterrent and backfiring effect cities?” The data showed that the strongest single area difference was to be found “in the proportion of black suspects, which averaged 63 % in the three backfiring cities.. .compared to 36 % in the three deterrent effect cities” (Sherman 1992, p. 18). In other words, differing community characteristics (including social disadvantage) in the six cities seemed to be at least partially relevant to the explanation of the results. On an individual (as opposed to areal) basis, the study also found that arrest was most likely to suppress subsequent violence if the suspect had high “stakes in conformity” (= employed and married) and least likely to suppress it when he had no such stakes (= unemployed and unmarried). Aspects of the interpretation of these results remain tentative, but it does seem from this research that the familial and communal relationships within which a person is embedded can significantly affect the manner in which he responds to an arrest (in principle, from deep shame to resentment against unfair police practices), and that such differences could affect the probability of subsequent violence against a partner. Referring back to an earlier discussion, one might add that the extent to which the policing in a neighborhood appears to its residents to be legitimate also seems potentially relevant – and this also might vary by social-structural context.

Before leaving the topic of social structure, a word must be added on the subject of housing markets. Housing markets are of great importance for the study of crime and criminality in residential areas, because the mechanisms of such markets strongly frame both who enters a given area as a resident, and how easy or difficult it is to leave the area if and when one wishes to do so. Of course, housing markets are often strongly influenced by economic factors (the rich buy large houses in desirable areas; the poor do not). However, economic factors are certainly not the only variables in play in shaping the operation of a housing market in a given area, for example, cultural questions or the reluctance of older residents to move might be very important in influencing exit decisions, and in some countries the allocative rules of public (or social) housing authorities are also relevant. In consequence, it is even possible for two adjacent areas with nearly identical economic and demographic characteristics to have radically different victimization and resident offender rates, flowing from the direct and indirect consequences of housing market processes (Bottoms et al. 1989). In short, as Robert Sampson (2009a, p. 90) has rightly commented, “because housing markets act as a mechanism of allocation, .. .they.. .need to be better integrated into sociological and criminological theory.”

Social Action

The third and final conceptual dimension to be considered, social action, is by its nature more dynamic than the other two – social actions are, after all, usually taken in an attempt to achieve certain consequences. Accordingly, this section contains more discussion of longitudinal theorization and research than previous sections.

The most famous longitudinal theory in contemporary geographical criminology is the broken windows hypothesis, originally formulated by Wilson and Kelling (1982) albeit in a somewhat informal and discursive manner. Taylor (2001, p. 98) has usefully formalized the proposed sequential stages of the Wilson-Kelling thesis; slightly modified, these stages are:

(i) Unrepaired low-level signs of incivility (e.g., broken windows, graffiti) appear in an area.

(ii) The local residents tend to withdraw from public areas and become fearful.

(iii) Emboldened antisocial locals commit more petty crimes, signs of incivility grow.

(iv) Local residents become more fearful and withdraw more.

(v) [Frequently but not inevitably]: Serious offenders from other areas note the lack of guardianship in the area and move in.

Thus, according to Wilson and Kelling (1982, p. 32), “the citizen who fears the ill-smelling drunk, the rowdy teenager or the importuning beggar is not merely expressing his distaste for unseemly behavior, he is also giving voice to a bit of folk wisdom that happens to be a correct generalization – namely, that serious street crime flourishes in areas in which disorderly behavior goes unchecked.” As regards policy responses, for Wilson and Kelling (p. 36) “the key is to identify neighborhoods at the tipping pointwhere the public order is deteriorating but not unreclaimable.” But others have gone further, linking the “broken windows” approach to zero tolerance policing, as in the following statement by former British Prime Minister Tony Blair (2010, p. 493): “if you tolerate the low-level stuff, you pretty soon find the lawbreakers graduate to the high-level stuff. So cut it out at source: tolerate nothing, not even painting a street wall or dropping litter.”

Empirically speaking, the evidence about broken windows is mixed. On the one hand, the Dutch research previously cited shows that a breach of a social norm (such as uncleared litter) does indeed, in the short term, encourage the breach of other norms. On the other hand, those empirical studies that have attempted to evaluate the broken windows hypothesis on a long-term basis have found little supporting evidence for the proposition that “disorder leads to serious crime” (Sampson and Raudenbush 1999; Taylor 2001; Harcourt and Ludwig 2006; Sampson 2009b).

Although further research is needed, on present evidence two matters seem particularly likely to explain the apparent tension between the short-term and long-term effects of “broken windows.” The first is that the final stage of the proposed Wilson-Kelling sequence (“serious offenders from other areas move in”) might often fail to materialize. St. Jean’s (2007) Chicago research (see above) showed that such offenders were usually more interested in nonresidential than residential areas as attractive sites for their activities; moreover, physical (as opposed to social) incivilities in residential neighborhoods were of no special interest to them. Secondly, the suggestion made by Tony Blair and others that one must “cut [incivilities] out at source,” or a downward spiral to “the high-level stuff” will inevitably occur, is incorrect. On the contrary, the literature contains several case examples of communities acting successfully at a later stage to ameliorate a downward spiral.

One such example is described in research by Taub, Taylor, and Dunham (1984). These researchers showed that two Chicago neighborhoods with high crime rates not only received positive “satisfaction with safety” scores in a residents’ survey but also had rapidly appreciating residential property values. How did this unusual combination of factors arise? In both the areas concerned, “there [were] highly visible signs of extra community resources being used to deal with the crime problem” (Taub et al. 1984, p. 172). This observation has to be set within the context of another finding in the study, namely, that, in evaluating local areas, people make a generalized, gestalt judgement, taking into account a range of positive and negative factors, of which crime (and, by implication, disorder) is one. Within such a framework, the injection of “visible signs of extra community resources” is clearly a potentially positive factor.

The term “visible signs,” used by these authors, is highly congruent with the later development, within the signal crimes perspective, of the concept of “control signals” (used in SgCP alongside the concepts of “signal crimes” and “signal disorders” – see above). “Control signals” are acts (particularly those taken by officials or by informal community leaders) that communicate (“send signals”) to the general public, in a way that helps to promote the general sense of order in a neighborhood. An example within the Taub, Taylor, and Dunham research concerned the neighborhood that includes the University of Chicago. Anxious about decline in the area, university managers invested heavily in the local urban infrastructure and helped to introduce various initiatives that directly addressed citizens’ worries about safety in public space – such as a private security force, 24-h “safety buses” and emergency telephones (Taub et al. 1984, pp. 99–102). This whole package of measures seemed to send a strong “control signal”; for while crimes such as burglary remained high (pp. 21–22), as previously noted, the area was perceived by the residents as safe, with rapidly appreciating property values. Thus, utilizing the trilogy of concepts around which this research paper is structured (space, social structure, social action), this was a powerful example of how social action can help to shape the future of a neighborhood. It seems likely – although we do not yet have fully confirmed evidence of this – that less dramatic but not dissimilar kinds of social action are not infrequently taken in other apparently declining local areas, with positive effects; and perhaps the apparent effect of improved street lighting on daytime crime levels (see above) results from similar social mechanisms. If these suggestions are correct, they could of course help to explain the lack of long-term evidence in support of the broken windows hypothesis.

It is not accidental, however, that in the above example the University of Chicago is a corporate actor. It is much easier for a corporate actor than an individual resident to send successful control signals; indeed, as Taub and his colleagues point out, for an individual household in a declining area, the instrumentally rational course of action will usually be to try to make a fast exit from the area. Thus, effective social action to halt social decline will probably normally require a lead to be taken by a public agency, a major private institution, or an active community organization. Thereafter, however, it is likely that local citizens will respond positively to the lead and feel emboldened to play their part in neighborhood renewal: recall that Keizer’s (2010) experimental research in the Netherlands suggests that actions to reinforce prosocial norms, as well as actions that breach such norms, can have a “contagious” effect on the behavior of others in a locality.

Yet a final caveat is required. Sherman’s (1992) study of domestic violence showed that police actions such as arrest can sometimes “backfire”; and the same, it would seem, is true also of residents’ social action. For various technical reasons, it is not easy to provide a definitive explanation of the strikingly different results for boys and girls in the MTO experiment (see more fully Bottoms 2012). The most plausible account of the counterintuitive result for MTO boys is to be found in a detailed qualitative study in two cities (Baltimore and Chicago: see Clampet-Lundquist et al. 2011). According to this research, one of the factors in operation in these cities was that the adolescent boys who moved to less poor neighborhoods continued, in their new environments, to practice the dominant leisure activity they had learned in their previous home area, namely, “hanging out” with one another in public places. But, in the changed context, they found themselves less accepted by the local residents (possibly because these residents were wary of adolescent males who were known to have moved from stigmatized public housing projects). Moreover, the new areas had higher collective efficacy than the baseline neighborhoods and therefore – see earlier discussion – more adult interventions with teens. In consequence, “a negative side of collective efficacy” seemed to be apparent, that is, adult interventions were made, but they led to resentment from the boys (Clampet-Lundquist et al. 2011, p. 1171). This example therefore once again illustrates the very complex social dynamics of neighborhoods – dynamics that need to be taken fully into account in the study of the geography of crime and disorder.

Conclusion

Within the broad field of the geography of crime, a great deal of excellent research has been completed in the last two decades. However, much of this work has been conducted in relative isolation from those working in other parts of the field. A strong case can therefore be made for the adoption of a more integrated approach. Such an approach should in particular seek to synthesize more fully the work in the “hotspots,” “neighborhood effects,” and “signal crimes” traditions, each of which has contributed powerfully to our overall understanding of geographical aspects of crime and disorder. Such a synthesis should lead to improved understanding of the very complex social dynamics in play within this field. Potentially, also, it could have an important payoff in improved crime prevention, given the persuasive case that has recently been made for “the importance of place in policing” (Weisburd et al. 2010).

Bibliography:

- Blair T (2010) A journey. Hutchinson, London

- Bottoms AE (2012) Developing socio-spatial criminology. In: Maguire M, Morgan R, Reiner R (eds) The Oxford handbook of criminology, 5th edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Bottoms AE, Mawby RI, Xanthos P (1989) A tale of two estates. In: Downes D (ed) Crime and the city. Macmillan, London

- Bottoms AE, Tankebe J (2012) Beyond procedural justice: a dialogic approach to legitimacy in criminal justice. J Crim Law Criminol 102:119–170

- Bowers KJ, Johnson SD, Hirschfield A (2004) Closing off opportunities for crime: an evaluation of alley-gating. Eur J Crim Policy Res 10:285–308

- Braga AA, Weisburd DL (2010) Policing problem places. Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Brantingham PL, Brantingham PJ (1981) Notes on the geometry of crime. In: Brantingham PJ, Brantingham PL (eds) Environmental criminology. Sage, Beverly Hills

- Brantingham PL, Brantingham PJ (2008) Crime pattern theory. In: Wortley R, Mazerolle L (eds) Environmental criminology and crime analysis. Willan Publishing, Cullompton

- Briggs X de S, Popkin SJ, Goering J (2010) Moving to opportunity: the story of an American experiment to fight ghetto poverty. Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Clampet-Lundquist S, Edin K, Kling JR, Duncan GJ (2011) Moving teenagers out of high-risk neighborhoods: how girls fare better than boys. Am J Sociol 116:1154–1189

- Clarke RV, Mayhew P (1988) The British gas suicide story and its criminological implications. In: Tonry M, Morris N (eds) Crime and justice: a review of research, vol 10. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Cohen LE, Felson M (1979) Social change and crime rate trends: a routine activity approach. Am Sociol Rev 44:588–608

- Felson M, Boba R (2010) Crime and everyday life, 4th edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks

- Harcourt BE, Ludwig J (2006) Broken windows: new evidence from New York City and a five-city social experiment. Univ Chic Law Rev 73:271–320

- Innes M (2004) Signal crimes and signal disorders: notes on deviance as communicative action. Br J Sociol 55:335–355

- Keizer K (2010) ‘The spreading of disorder’, proefschrift, University of Groningen. http://irs.ub.rug.nl/ppn/329349163

- Keizer K, Lindenberg S, Steg L (2008) The spreading of disorder. Science 322:1681–1685

- Kling JR, Liebman JB, Katz LF (2007) Experimental analysis of neighborhood effects. Econometrica 75:83–119

- St Jean PKB (2007) Pockets of crime: broken windows, collective efficacy and the criminal point of view. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Sampson RJ (2006) Collective efficacy theory: lessons learned. In: Cullen FT, Wright JP, Blevins KR (eds) Taking stock: the status of criminological theory. Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick

- Sampson RJ (2009a) Analytic approaches to disorder. Br J Sociol 60:83–90

- Sampson RJ (2009b) Disparity and diversity in the contemporary city: social (dis)order revisited. Br J Sociol 60:1–31

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW (1999) Systematic social observation of public spaces: a new look at disorder and crime. Am J Sociol 105:603–651

- Sherman LW (1992) Policing domestic violence: experiments and dilemmas. Free Press, New York

- Sherman LW, Gartin PR, Buerger ME (1989) Hot Spots of predatory crime: routine activities and the criminology of place. Criminology 27:27–55

- Taub R, Taylor DG, Dunham JD (1984) Paths of neighborhood change: race and crime in urban America. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Taylor RB (2001) Breaking away from broken windows: Baltimore neighborhoods and the nationwide fight against crime, grime, fear and decline. Westview, Boulder

- Weisburd D, Bernasco W, Bruinsma GJN (eds) (2009) Putting crime in its place: units of analysis in geographic criminology. Springer, New York

- Weisburd D, Groff ER, Yang S-M (2012) The criminology of place: street segments and our understanding of the crime problem. Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Weisburd D, Telep CW, Braga AA (2010) The importance of place in policing: empirical evidence and policy recommendations. Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention (Bra˚), Stockholm

- Welsh BC, Farrington DP (2008) Effects of improved street lighting on crime. The Campbell Collaboration, Oslo

- Wikstro¨ m P-OH, Loeber R (2000) Do disadvantaged neighborhoods cause well-adjusted children to become adolescent delinquents?: a study of male serious juvenile offending, individual risk and protective factors, and neighborhood context. Criminology 38:1109–1142

- Wikstro¨ m P-OH, Oberwittler D, Treiber K, Hardie B (2012) Breaking rules: the social and situational dynamics of young people’s urban crime. Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Wilson JQ, Kelling G (1982) Broken windows. The Atlantic Monthly (March), pp 29–38

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.