This sample Measuring Police Performance Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Successful organizations have one critical thing in common: they get the right people on the bus (Collins 2001). Selecting top quality individuals is a critical first step in creating a highly effective organization. In general, this is true but nowhere is it more the case than in a police department. Consider the fact that in almost every other type of organization, deficiencies in selection can at least be partially corrected by successfully introducing supervisors and other leaders from outside the organization. In police departments, it is rare, in fact highly unlikely, that supervisors and other leaders come from anywhere else except those who joined the force as new officers. The pool of applicants for promotions and ultimately departmental leadership is almost exclusively made up of individuals who have come up through the ranks. Ineffective selection programs and the inevitable hiring mistakes that occur even with the best selection processes result in limitations in not only current officers’ performance but also in the quality of the candidate pool for promotions.

While getting the right people on the bus or in the present case, into the patrol car, is vital to organizational success, it is equally important that organizations possess well-developed performance appraisal systems to motivate and improve performance of those on the force. Such systems are essential to providing developmental feedback to officers, helping organizations increase the readiness of officers for their current assignments as well as future positions, and understanding where the department’s strengths and developmental opportunities exist. Unfortunately, it is the exception rather than the rule that a department has an effective system for appraising and managing officer performance. This missed opportunity for improving the effectiveness of the department can be reversed.

The following entry addresses the role that performance appraisal research can play in the evaluation of police officer performance. First, key areas of research on performance appraisal in organizations will be summarized, pointing out traditional issues found in theory, research, and practice. Next, information is offered on those system elements that lead to effective performance appraisal programs. The process of system implementation is also presented, including preparing officers for performance evaluations, steps departments can take to create a positive environment for launching the process, and proper training of supervisors who will be the evaluators. The paper also addresses issues related to providing performance assessment feedback to officers. Highlighted also is the critical role of trust in the feedback process and the creation of an organizational climate conducive to performance feedback. Finally, the paper concludes with a discussion on the future of performance appraisal and management broadly and specifically within law enforcement organizations.

Key Research Questions In Performance Appraisal

How do we define performance? – Industrial psychologists have debated the definition of performance for decades. Austin and Villanova (1992) referred to this issue as the “criterionproblem,” suggesting that traditional measures of job performance fail to conceptualize and measure performance constructs that are complete, accurate, and multidimensional in nature. Specifically, such measures often suffer from criterion deficiency and contamination. While the former refers to aspects of the performance domain not measured by the appraisal instrument (leaving out of the evaluation critical performance factors), the latter refers to specific measurement error created by including in the assessment measures that are either not part of the job requirements or things that are out of the control of the officer being evaluated (i.e., unrelated elements that are unintentionally measured as a part of the performance domain). As such, work psychologists have underscored the importance of conducting a thorough job analysis to fully define the performance domain, develop a holistic understanding of key job-related behaviors, and thereby develop a valid appraisal system.

Before conducting a job analysis, however, it is important to have an understanding of what performance means in a given job. Campbell (1999) defined performance as “behavior or action that is relevant for the organization’s goals and that can be scaled (measured) in terms of the level of proficiency (or contribution to goals) that is represented by a particular action or set of actions.” (pp. 402–403). Motowidlo (2003) defined performance as “the total expected value to the organization of the discrete behavioral episodes that an individual carries out over a standard period of time” (p. 51). In short, performance is what employers pay employees to do (Campbell 1999). In the context of police performance, it includes departmental expectations, as well as what the public demands (viz., behaviors associated with preserving life and property).

Additionally, job performance can be described in terms of two broad arenas, task performance and contextual performance. Task performance is related to the core elements of the job while contextual performance supports the organizational, social, and psychological environment in which the task performance occurs.

For example, while task performance for police officers might include monthly documentation of traffic stops, creating accurate reports, testifying in court, and listening to citizens describing events, contextual performance includes behaviors related to boosting squad morale, providing counsel to a fellow officer, or being available for additional assignments. Both factors contribute independently to overall performance ratings.

What have we done to better understand performance assessment? – Much of the research on performance appraisal (PA) prior to 1980 was dominated by measurement issues and the search for “the right” rating format. This research focused on comparing various rating formats, including graphic ratings scales, behaviorally anchored ratings scales, traditional Likert scales, behavioral checklists, and other formats (Jacobs et al. 1980; Landy and Farr 1980). However, after thirty years of research on the topic, the field became less interested in issues of rating formats, concluding that although raters may have a preference for one format over another, differences in ratings due to format are minimal and overall inconsequential when it comes to the overall performance information provided to the individual and the organization. They did, however, note that behavioral anchors are better than simple numerical scales or ones that rely on common adjectives, and that anchoring should be based on methods that are grounded in firm psychometric theory. In fact, right now any organization, police or other, can find a variety of tools for measuring performance and can be ready to launch a program without the burden of creating a site-specific rating form. With respect to police officer performance, the reader of this research paper can contact the senior author and receive a set of scales to be used for officers, supervisors, or command personnel.

Moving beyond issues of rating format, researchers began to consider the role of rater cognition in the performance appraisal process, leading to a flurry of research on the topic during the 1980s. During this time, increased attention was paid toward understanding how raters reach their judgments of employee performance. Such research targeted various cognitive processes of raters including observation and information acquisition, encoding and categorization, storage, retrieval, integration, and evaluation (Murphy and Cleveland 1995). Moreover, one of several themes to emerge from this literature was the effects of raters’ implicit theories on ratings, including the tendency for raters to commit various rating errors including halo, leniency, and systematic distortion based on assumed rather than actual ratee behavior (Ostroff and Ilgen 1992).

The 1990s brought with it an emphasis on performance appraisal as embedded within the larger social-organizational context (Ilgen et al. 1993). Specifically, Ilgen and colleagues (1993) suggested that the appraisal process as entrenched within a rating environment or “social milieu” that raters and ratees occupy during that process. Performance appraisal became an even more complex process, given this newer socialpsychological approach emphasizing a variety of contextual influences on performance ratings. Specifically, performance appraisal began to be viewed as a function of several different categories of environmental factors, including distal variables (i.e., organizational climate, culture, economic conditions, etc.), process proximal variables (rater accountability, feedback environment, etc.), structural proximal variables (appraisal goals and purpose, appraisal training, etc.) and rater and ratee behavior (i.e., rater/ratee attitudinal reactions, cognitive reactions, perceptions of justice, etc.). While cognitive research during the 1980s served to shed light on the limits of raters to make accurate ratings, the social-organizational approach expanded our view of the appraisal process by incorporating issues of rating context into the discussion.

More recent research has tended to focus on motivation and reactions to appraisal processes (Levy and Williams 2004). In terms of motivation, it appears that participation in the appraisal process is critical to motivating employees, who must perceive the appraisal system as fair and ethical. With regard to ratee reactions, research has tended to focus on system and session satisfaction on the part of the person being evaluated, perceived utility and accuracy of the performance information, and various forms of justice including procedural, distributive, and interactional, as well as due process. One important finding, in particular, by Folger, Konovasky, and Cropanzano (1992), suggests that perceptions of fairness are achieved when adequate notice, fair hearing, and judgment based on evidence are present in the appraisal system. In general, it appears that fair appraisal systems lead to a wide array of positive rater and ratee outcomes, including less emotional exhaustion, increased acceptance of feedback, more positive reactions to one’s supervisor and the organization, and more satisfaction with the appraisal system and the job by the rater and ratee.

Moreover, ratees’ reactions seem to be strongly tied to the opportunity to participate in the appraisal process and the amount of information provided about the process (Cawley et al. 1998). Other research suggests that aspects of the leader-member relationship may impact ratee evaluations. In particular, trust (a topic that will be returned to later), and specifically trust in one’s supervisor, seems to be particularly important in predicting both incumbents’ and supervisors’ acceptance of their appraisal and satisfaction with the appraisal system (Hedge and Teachout, 2000). Further, the presence of a feedback culture, often enhanced by trust and strong supervisor-subordinate relationships, has been empirically related to satisfaction with feedback, motivation to use feedback, and feedback seeking (Steelman et al. 2004).

Finally, a considerable amount of work has addressed the role of rater training in the appraisal process and that work supports the importance of properly training those responsible for conducting performance evaluations. While a variety of methods are available to train raters, the general consensus is the most effective rater training is achieved using what is known as frame-of-reference (“FOR”) training (Sulsky and Day 1992).

The performance appraisal literature has come a long way in the past sixty years. What began with research primarily dedicated to measurement issues and the search for the perfect rating format was followed by two shifts in the research literature, the cognitive approach of the 1980s, and the social-organizational perspective of the 1990s. This rich research history has provided us with a strong empirical framework for designing effective performance appraisal systems. Clearly, performance assessment is more than just assigning numerical values to a few categories that loosely reflect what an officer has done over the past year. Given this historical backdrop, the next section highlights system elements that lead to effective programs and evidence for performance improvement as a result of such systems.

Steps In Successfully Implementing A Performance Appraisal Programs

The Preamble: Setting the stage – Defining which competencies are required to effectively perform as a police officer is the first step in providing a framework for a useful performance appraisal and management system. However, once these competencies are in place, the question of how to best create a system that accurately measures these competencies still remains. There are a variety of aspects to consider when implementing a performance appraisal system. From training the raters to using the resulting data to make administrative decisions, there are many pieces of the performance appraisal puzzle that have to be in place in order to ensure success.

Often overlooked, some of the most important parts of the performance appraisal process take place even before the system is put in motion. For example, departments need to first ensure that officers are aware of the competencies being evaluated, how they are linked to the job, and why they are important. As referenced previously, this method of performance appraisal implementation is called “due process.” Due process refers to a lifecycle approach to performance appraisal – one in which officers are informed from the start which competencies are important in defining job performance and which behaviors are viewed as effective or ineffective. This would provide officers with a clear understanding of how performance ratings will be derived.

Ensuring that officers are “on board” with the way in which performance is defined and measured, as well as the key features of the system, will result in an environment of trust in the appraisal process, as opposed to suspicion. One common finding from both research and practice is that employees do not like being evaluated. Thus, creating clear guidelines for performance from the start allows organizations to avoid the potential for surprise during the evaluation process, and enhances the overall perceptions of system fairness. Employees who perceive political motives underlying the performance appraisal process are likely to have lower job satisfaction and affective commitment, which were both found to be negatively related to job performance.

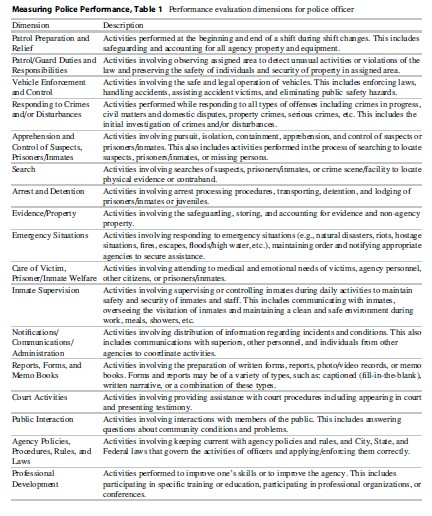

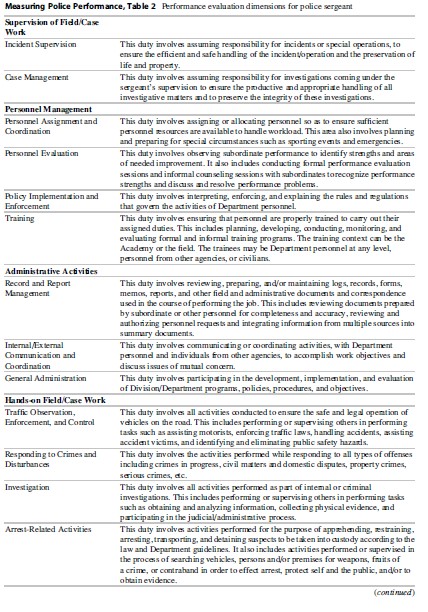

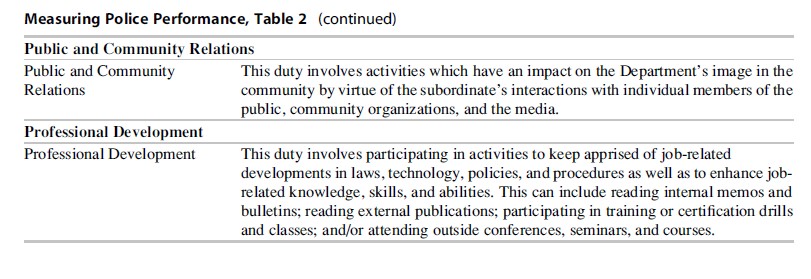

Ensuring that employees perceive the performance appraisal process as valid and worthwhile is important for maintaining a productive and satisfied workforce. Table 1 reflects a list of areas of responsibility for police officers and the basics upon which a system can be built for evaluating the performance of police officers. As can be seen, the areas of performance being rated are specific and clearly a part of a police officers’ job. Specific performance assessment scales further enhance the performance evaluation process for each of the areas. Table 2 reflects a similar list that represents police supervisor/sergeant. Scales based on this type of approach are available by contacting the senior author of this research paper.

In addition to presenting employees with clear and relevant criteria, it should also be made salient that it is possible for employees to voice their opinion if a part of the system appears to be unfair or unclear. The ability to participate in the appraisal process by respectfully questioning the system is also a part of due process. In line with this idea, Cawley et al. (1998) empirically demonstrated the effects of employee participation in the appraisal process. The authors found that employees had more favorable reactions to a performance appraisal system in which they could voice their opinion about the accuracy of their performance ratings and the system in general, regardless of whether or not the feedback would have an impact on organizational practice in the future. Thus, it is clear that employees are more comfortable with appraisal when they are well informed and feel that they have the opportunity to provide input about the system.

Rater Training: An Absolute Requirement – Once the performance appraisal system has been rolled out, it is important to identify those individuals who will be responsible for providing ratings and to properly train them to use the system. As discussed previously, raters may fall prey to a variety of rating biases, such as halo (employees are either all good or all bad) or leniency (every employee is great) without proper training. Further, raters may decide to pursue personal goals when providing ratings for their officers (e.g., providing low ratings to an exemplary officer as a motivator for even better performance or providing high ratings to a poor performing officer to get them out of a particular unit and under someone else’s command). There is also evidence that when raters have other goals in mind such as promoting harmony and a sense of equality across ratees, their ratings tended to be less discriminating, no longer sorting strong performers from weak ones and resulting in higher ratings in general. This provides support for the notion that when raters have a goal in mind, they can paint a picture of performance that is in alignment with that goal but not necessarily consistent with what they observe.

In the end, a system is only as good as the people who use it. It is completely possible for an organization to have a fantastic performance appraisal system in place and still achieve mediocre or even disastrous results. Thus, it is helpful to view the performance appraisal system as a vehicle – all of the parts may be in place but, without a properly trained driver and periodic servicing, the car does not function properly and thus at risk of malfunctioning. That being said, providing rater training is clearly a key component of a successful performance appraisal process.

As mentioned earlier, one type of rater training that has been touted as particularly effective in driving an accurate performance system is frame-of-reference (FOR) consisting of a variety of components which all help to make certain that raters will be able to accurately assess officers’ behavior. FOR training helps in creating a unified definition of performance across raters, so that officers will receive similar ratings regardless of their rater. As such, FOR training is an extremely valuable tool for increasing the validity and predictive capabilities of performance ratings. FOR training alsoprovides raters the opportunity to practice assessing behavior and to compare ratings with other raters to help provide a consistent and clear basis upon which raters should be formulating performance ratings. For example, raters who can effectively evaluate officers will gain additional and reinforcing insights from the training, while officers who are not accomplished performance evaluators will learn important skills and gain confidence in their ability to properly evaluate others. Systems that fail to provide rater training (i.e., FOR) will be far less effective.

Of equal concern for performance management efforts is feedback. Anxiety and lower levels of motivation in ratees often arise from misused and improperly delivered feedback. In the next section, proper feedback delivery and environment will be discussed to ensure that organizations are making the best possible use of performance information. As should be obvious, any rater training process must include information on the proper conduct of the feedback process.

Feedback In Performance Appraisal

Reference different fields of study and you will find various ways in which the term “feedback” has been conceptualized and defined. Industrial psychologists generally refer to feedback as information provided to an individual that clarifies expectations of their job and alerts them to how well their current performance meets such expectations (Ashford and Cummings 1983; Spector 2006). Although it was long assumed that employee feedback resulted in positive gains in performance, a meta-analysis by Kluger and DeNisi (1996) exposed the reality that feedback not only has the potential to produce performance gains, but also performance declines. As Taylor, Fisher, and Ilgen (1984) note, “Feedback may have no impact on the recipient at all, it may cause the individual to lash out angrily, or it may result in a response quite different from that desired by the source” (p. 82). Ilgen, Fisher and Taylor (1979) suggest that variability in response to feedback might be due to a series of psychological or cognitive processes elicited by the feedback process.

Many studies have sought to determine what characteristics of the feedback process contribute to its effectiveness or lack thereof but before considering such characteristics, it is important to understand that the effectiveness of any feedback system hinges upon recipients’ acceptance of such feedback (Ilgen et al., 1979). Ilgen and colleagues (1979) defined feedback acceptance as “the recipient’s belief that the feedback is an accurate portrayal of his or her performance” (p. 356). One way to think about this is that feedback acceptance acts as a gatekeeper or moderator between feedback delivery and effectiveness. Using self-consistency theory, Korman (1970) argued that, “individuals will be motivated to perform on a task or job in a manner which is consistent with the self-image with which they approach the task or job situation” (p. 32). Thus, one’s response to performance feedback is expected to be congruent with his or her acceptance of such feedback. As such, positive or negative feedback, which is perceived as accurate and therefore accepted by the recipient, is more likely to motivate one to respond than feedback which is perceived as inaccurate.

Given the crucial role feedback acceptance appears to play in the feedback delivery performance relationship, what factors might predispose recipients to perceive feedback as inaccurate and unacceptable, and what can organizations do to foster acceptance? In the following sections, the effects of feedback content, specificity, frequency, delivery, and source on individuals’ willingness to accept and utilize performance feedback will be discussed. Moreover, the role of trust in the feedback process will be explored, as well as how organizations can create environments conducive to feedback.

Feedback Content – Given the sensitive and potentially anxiety-inducing nature of feedback in organizations, it is no surprise that the content of feedback may have a substantial impact on the likelihood of feedback acceptance. In general, individuals are more accepting of positive feedback, which likely stems from the motivation to preserve one’s self-esteem from the perceived failure resulting from negative feedback. Individuals are more likely to reject feedback that reflects discrepancies between one’s actual performance, relayed through feedback, and one’s perceived performance.

This does not necessarily indicate that individuals wholly reject negative feedback. It does indicate, however, that when performance discrepancies exist, individuals prefer positive feedback signs that portray them in a positive light and confirm their own self-perceptions. Moreover, it suggests that feedback providers ought to balance their negative feedback with positive feedback in order to reduce perceived performance overestimations as much as possible. By narrowing the perceived gap between one’s actual performance and perceived performance, feedback providers may be more likely to gain feedback acceptance, which in turn may lead to performance improvements on the part of feedback recipient. Additionally, Smither and Walker (2004) showed that providing a small amount of negative feedback enhances performance, but that a large amount of negative feedback impairs future performance. Atwater and Brett (2006) further suggest that feedback sessions should begin with positive feedback in order to spur feedback acceptance. Thus, feedback providers should be aware of the amount of negative feedback they provide, making sure to buffer it with positive feedback at the beginning of the feedback session and ensuring that subordinates are not overwhelmed by too much negative feedback during the process.

Other research indicates that feedback is perceived as valuable when it helps employees reduce uncertainty, provides recipients information regarding their goal progress, and indicates how one’s performance is being evaluated by others. Additionally, feedback is more likely to be accepted and used when it is perceived as valid, accurate, and reliable. Thus, feedback providers should always err on the side of providing higher quality feedback during feedback sessions.

Kluger and DeNisi (1996), however, note that such feedback ought to be focused more on the performed task than the person receiving the feedback. In their influential meta-analysis, they found that feedback intervention (FI) effectiveness decreased as feedback became more directed toward the feedback recipient than the task. This is consistent with other research that supports the idea that individuals are more likely to accept feedback that compares them to a neutral standard, rather than to their peers. It is believed that such comparisons can hurt recipients’ self-concept and reduce their likelihood of accepting feedback. This suggests that recipients may be less likely to accept and ultimately use feedback that they perceive as a personal attack rather than an honest assessment of performance on the task. Thus, feedback providers should be careful that their feedback is not directed toward personal characteristics or compares recipients to their peers, but rather should focus on specific performance aspects related to the task.

Feedback Specificity – To date, feedback specificity, or the level of information presented in feedback messages, has received quite a bit of attention in the performance appraisal literature. Generally speaking, it is believed that effective feedback includes specific information about behaviors that were performed incorrectly and how to correct them, rather than statements that are generalized or ambiguous. Such feedback provides a rich source of information about explicit behaviors that are appropriate or inappropriate for effective performance, thereby allowing recipients to learn from and correct their behavior. In doing so, feedback specificity is thought to decrease information-processing activities such as error diagnosis, encoding, and retrieval, which subsequently reduce the cognitive load required to make links between actions and outcomes. Moreover, specific feedback provides information on how individuals are progressing toward their goals and informs them about how their job performance is being evaluated.

In fact, empirical evidence suggests that specific, objective feedback that is consistent with actual performance leads to higher performance than less specific, more subjective feedback. Moreover, feedback interventions that are supplemented with information regarding tasks, strategies, and appropriate behaviors have been found to result in increased short-term performance during practice and training. Interestingly, Steelman and Rutkowski (2004) demonstrated that employees are motivated to use negative feedback when it is perceived to be of high quality and directed toward improving their performance than similar feedback of lower quality.

Despite such findings, overly specific narrative feedback may also introduce excessive cognitive load on recipients, hindering their understanding of the feedback. The positive impact of feedback can clearly be enhanced when the information being conveyed is easy to consume and in a form that is readily understood by the recipient. This point argues for a graphic presentation of information as perhaps a takeaway from the feedback session. It may also include the use of summary statistics that make it easy to compare current performance to expectations or even to the performance of peer groups.

In general, research has suggested that specific feedback is more effective than vague, generalized feedback. Employees must learn which specific behaviors are indicative of good and poor performance – not only so that they can correct such behaviors but also in order to protect against perceptions of arbitrariness in the feedback process.

Feedback Frequency – Feedback frequency has also been explored as a potential factor influencing feedback acceptance and perceived utility. In general, it is thought that frequently delivered feedback is more effective in promoting performance improvements than less frequent feedback. The logic that drives this conclusion is that the close temporal pairing of feedback with employee performance behavior has an overall positive effect on future performance. Frequently delivered feedback reduces the chances that interference will occur in the periods between behavior and the feedback, which have the potential to distort feedback effectiveness. This stands in stark contrast to most performance evaluation processes, which call for assessment and feedback once per year. In the course of performing any job and especially a police officer’s, much can happen over that 12-month period.

In fact, research suggests that frequency of feedback is positively related to recipients’ perceived accuracy and fairness of feedback. Because feedback tends to not be delivered as frequently as it should in today’s organizations, recipients may view feedback as a scarce, valuable resource that decreases role ambiguity by continually informing employees about where they stand with regard to their performance levels. Thus, increasing the frequency of feedback may facilitate more positive employee reactions and outcomes during the feedback process. While once per year seems too little, other factors must be taken into consideration when deciding whether to provide more frequent feedback. For example, instituting more frequent feedback sessions may send implicit messages to employees that supervisors do not trust them as being competent and capable of carrying out their tasks without increased micro-management. In fact, it has been shown that while positive feedback provided immediately promotes a strengthening of previous behavioral responses, negative feedback is more effective after a time lag, which allows for decomposition in the strength of the previous incorrect behavioral response. As such, it stands to reason that while providing feedback on how to do a job may be perceived positively when done once or twice, such feedback may be reacted to more negatively when delivered in excess.

Supervisors should seek to provide regular feedback to employees, but they should also recognize that more is not always better. Specifically, because recipients’ feedback perceptions are crucial to its acceptance, supervisors should be aware that the intent behind providing increased amounts of feedback may not be perceived accurately by recipients. What may be intended as supportive may in actuality be perceived as controlling. One simple recommendation is that supervisors find out how often their employees desire feedback and use that in conjunction with the requirements of the organization to create a dialogue about performance.

Feedback Delivery – It is also important that feedback providers take active steps to preserve and respect recipients’ self-esteem by being sensitive and understanding in order to obtain feedback acceptance, rather than simply viewing their role as a provider of information. The manner in which feedback is delivered may significantly impact employees’ acceptance and perceived utility of the feedback. For example, it has been found that a supportive, constructive attitude on the part of feedback providers contributes to increased recipient satisfaction, perceptions of fairness, and motivation to improve job performance. Furthermore, feedback consisting of greater interpersonal fairness has been found to be related to more favorable attributions toward the feedback provider, greater acceptance of feedback provider, and more favorable reactions to the organization. Officers can be seen as motivated to improve their job performance following negative feedback when feedback is delivered in a considerate manner and with information that helps them better understand what was done improperly as well as what might be seen as more effective.

Feedback Source – Not surprisingly, much research has also investigated whether feedback acceptance depends on who provides such feedback. This research has often investigated the feedback source’s credibility, which refers to one’s expertise and trustworthiness in providing feedback. Expertise on the part of the person conducting the evaluation includes knowledge of the job requirements, knowledge of actual job performance, and the ability to evaluate performance in an accurate manner, while trustworthiness represents whether or not the individual being evaluated has a belief that the feedback source can and will provide accurate performance information.

Credible feedback providers are seen as possessing expertise relative to the specific tasks being evaluated and are trusted to provide feedback that is objective and free from bias (e.g., political considerations, feedback source’s mood at the time of feedback, etc.). In police settings, the former is generally the case since virtually every police officer providing evaluations came through the position they are evaluating (sergeants were police officers, lieutenants were sergeants, etc.). However, trust is a much more elusive characteristic, and one that must be developed over time between the evaluator and the officer being evaluated. This suggests that organizations should make a strong effort to ensure that feedback is delivered by highly qualified individuals with experience on the task being evaluated and professional status that is greater than the feedback recipient’s. In doing so, recipients may be more likely to both accept and use feedback in order to improve their future performance.

The Role of Trust in Feedback – Further examination of the feedback process highlights the importance of recognizing that feedback does not exist within a vacuum, but rather is embedded within the larger social-organizational context or what is often referred to as the “social milieu.” In fact, research suggests that context plays a potentially pivotal role in shaping aspects of the appraisal process, including feedback, and the ways in which employees react to such processes (Farr and Jacobs 2006; Murphy and Cleveland 1995). Specifically, Folger, Konovsky, and Cropanzano (1992) discussed performance appraisal as a process in which individuals at all organizational levels (including subordinates, supervisors, and upper management) have a stake, leading to potentially conflicting interests regarding the results of a given performance appraisal or feedback session. Feedback providers, in such contexts, are believed to hold power over subordinates, who inevitably make themselves vulnerable during such sessions. Therefore, in order for feedback sessions, and performance appraisal processes in general to be effective, those engaged in the process must trust in it. For feedback recipients, this means trusting their supervisors and the system used to evaluate them. For supervisors, this means having faith in the quality of their feedback and appraisal system that informs it.

An officer’s trust in their sergeant influences the communication link between the two. As trust fades, information fails to make a substantive impact during communication. Thus, it stands to reason that when trust decreases so does the impact of the sergeant’s feedback on officer’s behavior. Providing empirical support for this idea, Herold and Greller (1977) found that super- visors who were more “psychologically close” with their subordinates had a greater impact in terms of feedback than those who were more psychologically distant. In addition, Earley (1986) found that workers’ trust in the feedback source partially mediated the relationship between feedback and workers’ response to and value attached to praise and criticism. Jablin (1979) provides a nice overview of the supervisor-subordinate relationship and its importance in this context.

In sum, these findings suggest that trust plays a crucial role in individuals’ willingness to accept and respond to feedback. Thus, supervisors should actively try to promote trust among their subordinates by educating subordinates about the performance appraisal and feedback process, showing how the feedback process may be used to promote employee development, demonstrating consideration for employees’ work and well-being, exhibiting dependability on a regular basis, and communicating a sense of honesty and forthrightness in daily activities, among other things. In doing so, it may be possible to promote a climate of trust surrounding the feedback process, which will facilitate feedback acceptance and ultimately improved job performance.

Summary Of What We Know About Police Officer Performance Management

To this point, the primary focus has being on giving the reader a lot of information regarding research and practice as it pertains to performance assessment and management. Much has been done in this area and over the decades of theory building, research, and practical application, quite a bit have been learned. While the importance of being very specific about what has been done in the past is acknowledged, it is often important to step back and simply summarize what is known and what it means in terms of creating a successful performance management program. Here is the authors’ perspective.

Defining Performance – Without a doubt, nothing works unless time is spent and effort is expended to accurately define the key responsibilities and expected behaviors of those who are being evaluated. Traditionally, this starts with a job analysis or a very comprehensive job description. This step helps raters and ratees when it comes to understanding performance expectations and accepting the accuracy of performance evaluations. Further, with respect to fairness and meeting potential legal challenges, a system of performance management will never be seen as reasonable unless the agency has done its homework and clearly documented what is required by the job. These descriptions should be multidimensional covering critical areas of job performance and behaviors specifying the types of actions that represent poor, average, and strong job performance.

Setting the Stage – Performance management is not just an organizational requirement. It is an organizational event. In police agencies and other organizations, the process of evaluating performance is often approached with dread. Evaluators do not enjoy conducting evaluations, those being evaluated feel like they are being unnecessarily put under the microscope, and those responsible for the process within the HR organization often feel they have to harass and cajole individuals just to do what needs to be done. It is not a happy time of the year for many members of the organization. With this backdrop, it is important that a more positive environment is created. This can be accomplished by focusing on the process and potential positive outcomes that will result from effective performance management. Creating a positive environment requires a campaign initiated by the agency and supported from the top down. Without this kind of effort, the process will wallow in apathy, and the benefits will never emerge.

Training, Training, and More Training – Organizations consistently make a faulty assumption when it comes to performance appraisal and management. They too often assume that because someone has become a supervisor, they CAN and WILL be competent in the evaluation of others. Many supervisors and command personnel are good at reviewing the work of others and may enjoy the process, but not all. The role of training evaluators on the how to’s and why’s of performance evaluation is critical. Even for those who are positively disposed to the activity, training helps. An essential part of any performance management system is the training of raters on all aspects of the system.

It is also critical that those being evaluated are informed regarding the process (i.e., setting the stage), which is often a neglected area. While it may be an annual agency requirement that performance reviews will occur, it is not necessarily clear to individuals being evaluated exactly how the evaluations will be conducted, what is being measured, and how the data will be used. All these topics should be explained in advance of system implementation.

Keeping Track/Monitoring the System – The most effective processes do not stop at the collection of data and the checking off of yet another organizational event required by the agency. The best systems review results, hold raters accountable for doing the evaluations in a timely fashion, analyze data for potential problems (bias, halo, and missing information as examples), and use this information to enhance the future system implementations.

Using the Data – Traditionally data from performance evaluations are used to understand individual performance, to provide feedback to the person being evaluated, and/or to trigger personnel actions such as administering rewards or reprimands. While these are clearly important uses for the data, organizations are missing opportunities unless they look across individuals to understand where the agency may have repeated performance decrements indicating needed training programs, or where the department is truly excelling and how that information can be leveraged for future motivational programs. Suffice it to say, the best performance management programs continue beyond the individual level of analysis and look at groups, departments, and agency wide data to better understand performance.

Feedback – “Don’t collect information that you just put in a folder:” Over the years, quite a bit has been learned about how organizations can move from performance appraisal to using that information to drive future performance. It begins with a well-developed feedback process that brings supervisors and officers together to talk about the past and to plan for the future. Feedback does not happen automatically. Many involved in the process of delivering and receiving feedback need guidance to effectively turn observations of performance into performance improvements.

The Future Of Performance Appraisal And What It Means For Police Departments

Thus far, this research paper has outlined best practices for performance appraisal in organizations – from traditional issues regarding instrumentation to how to deliver performance feedback and the importance of trust between an evaluating supervisor and the officer being evaluated. However, performance appraisal methodology has never been stagnant. Changes have been seen in research emphasis and practice over the past five decades. The future will bring improvements and updates to best practice as it stands today. Although it is impossible to predict exactly what the future will hold, there are a few areas that have already begun to show promise, which may allow police departments to enhance the effectiveness of their performance assessment processes.

The first of these areas lies in the realm of online assessment. Online assessment is quick, easy, and fits in well with today’s demand for technology-driven solutions. For example, E-learning has become very popular in organizational training because it is easy to use and can be completed by employees at any time. The same is true for online performance appraisal systems. Supervisors can complete surveys about officer behavior at a convenient time and in a quick, easy fashion. As the computerization of police work marches forward, more and more systems will be available for documenting and evaluating police officer performance. The use of online performance appraisal also facilitates self-evaluation and lends itself to automated comparisons between subordinate and supervisor, which can form the basis of performance discussions and goal setting. Online assessments are also extremely useful tools for organizations because they save time, energy, and allow for the automated collection and storage of performance assessment data. Making performance appraisal systems user-friendlier and more efficient is undoubtedly in the best interest of the organization. And, online appraisals certainly help to propel these goals forward.

Second, there has been a recent upswing in the use of self-assessment for performance appraisal. In this case, employees are able to provide ratings regarding their own performance. However, the literature suggests that self-appraisals are ridden with bias. For example, Atkins and Wood (2002) demonstrated that self-ratings were negatively and nonlinearly related to assessment center performance. The worst performers may report that they are doing the best as a way of overcompensating for poor performance. Atkins and Wood’s (2002) findings further suggest that high performers may be hard on themselves, creating a performance profile much lower than that which exists in reality. It has also been demonstrated that self-ratings tend to be less variable than supervisor, peer, or subordinate ratings, suggesting possible halo or leniency errors (Scullen et al. 2003). Thus, while self-evaluations may provide interesting information, this information is not suggested for use in making administrative decisions. Organizations should be aware of employees’ intent to distort self-ratings and should proceed with caution when determining how to make use of self-report performance data.

Finally, it is time for police organizations to move away from the perspective that they conduct appraisals because their policies and procedures manual indicates they must do so to viewing the performance appraisal system as a vehicle for enhancing communication between supervisor and subordinate, facilitating change, and setting goals for the future performance. It is tempting to consider performance appraisal in police departments a truly lost opportunity but that seems excessively negative. Rather the tone of this research paper should convey the tremendous opportunity for organizational success that is embodied in well thought-out and well-executed programs in performance management and how they can truly transform a department. In this time of shrinking budgets and disappearing resources, developing and implementing a state-of-the-art performance appraisal system can be a very low cost, high impact process for any law enforcement agency. This research paper, hopefully, has helped convince you and has provided you with information that can move you forward in putting a performance management program into practice in your department.

Bibliography:

- Ashford SJ, Cummings LL (1983) Feedback as an individual resource: personal strategies of creating information. Organizational Behavior Human Performance 32:370–398

- Atkins PWB, Wood RE (2002) Self-versus others’ ratings as predictors of assessment center ratings: validation evidence for 360-degree feedback programs. Personnel Psychol 55:871–904

- Atwater L, Brett J (2006) Feedback format: does it influence manager’s reactions to feedback? J Occupational Psychol 79:517–532

- Austin JT, Villanova P (1992) The criterion problem: 1917–1992. J Appl Psychol 77:836–874

- Campbell JP (1999) The definition and measurement of performance in the new age. In: Ilgen DR, Pulakos E (eds) The changing nature of performance. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, pp 399–430

- Cawley BD, Keeping LM, Levy PE (1998) Participation in the performance appraisal process and employee reactions: a meta-analytic review of field investigations. J Appl Psychol 83:615–633

- Collins J (2001) Good to great. Harper Collins, New York

- Earley PC (1986) Trust, perceived importance of praise and criticism, and work performance. An examination of feedback in the United States and England. J Manage 12:457–473

- Farr JL, Jacobs R (2006) Unifying perspectives: the criterion problem today and into the 21st century. In: Bennett W, Lance C, Woehr D (eds) Performance measurement: current perspectives and future challenges. LEA, Mahwah, NJ, pp 321–337

- Folger R, Konovsky MA, Cropanzano R (1992) A due process metaphor for performance appraisal. Res Organizational Behav 14:129–177

- Hedge JW, Teachout MS (2000) Exploring the concept of acceptability as a criterion for evaluating performance measures. Group Organization Manage 25:22–44

- Herold DM, Greller MM (1977) Feedback: the definition of a construct. Acad Manage J 20:142–147

- Ilgen DR, Fisher CD, Taylor SM (1979) Consequences of individual feedback on behavior in organizations. J Appl Psychol 64:349–371

- Ilgen DR, Barnes-Farrell JL, McKellin DB (1993) Performance appraisal process research in the 1980s: what has it contributed to appraisals in use? Organizational Behav Human Decision Processes 54:321–368

- Jablin FM (1979) Superior-subordinate communication: the state of the art. Psychol Bull 86:1201–1222

- Jacobs RR, Kafry D, Zedeck S (1980) Expectations of behavioral rating scales. Personnel Psychol 33:595–640

- Kluger AN, DeNisi A (1996) Effects of feedback intervention on performance: a historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychol Bull 119:254–284

- Korman AK (1970) The prediction of managerial performance: a preview. Studies Personnel Psychol 2:4–26

- Landy FJ, Farr JL (1980) Performance rating. Psychol Bull 87:72–107

- Levy PE, Williams JR (2004) The social context of performance appraisal: a review and framework for the future. J Manage 30:881–905

- Motowidlo SJ (2003) Job performance. In: Borman WC, Ilgen DR, Klimoski RJ (eds) Handbook of psychology: industrial and organizational psychology. Wiley, Hoboken, NJ, pp 39–53

- Murphy KR, Cleveland JN (1995) Understanding performance appraisal: social, organizational, and goalbased perspectives. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

- Ostroff C, Ilgen DR (1992) Cognitive categories of raters and rating accuracy. J Business Psychol 7:3–26

- Scullen SE, Mount MK, Judge TA (2003) Evidence of the construct validity of developmental ratings of managerial performance. J Appl Psychol 88:50–66

- Smither JW, Walker AG (2004) Are the characteristics of narrative comments related to improvement in multirater feedback ratings over time? J Appl Psychol 89:575–581

- Spector PE (2006) Industrial and organizational psychology: research and practice. Wiley, Hoboken, NJ

- Steelman LA, Rutkowski KA (2004) Moderators of employee reactions to negative feedback. J Manag Psychol 19:6–18

- Steelman LA, Levy PE, Snell AF (2004) The feedback environment scale: construct definition, measurement, and validation. Educational Psychol Measure 64:165–184

- Sulsky LM, Day DV (1992) Frame-of-reference training and cognitive categorization: an empirical investigation of rater memory issues. J Appl Psychol 77:501–510

- Taylor MS, Fisher C, Ilgen D (1984) Individuals reactions to performance feedback in organizations: control theory perspective. In: Rowland K, Ferris G (eds) Research in personnel and human resource management. JAI, Greenwich, CT, pp 81–124

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.