This sample Organized Fraud Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

The relationship between fraud, organized crime, and white-collar crime is a complex one.

When Sutherland (1945) wrote his classic presidential address for the American Sociological Association toward the end of the Second World War, “White-collar crime is organized crime,” he was pointing to the “organizedness” of the crimes committed by the otherwise legitimate corporations he had researched as well as, perhaps, appropriating some of the demonization that attaches to the “organized crime” label. Later theorists such as Shapiro (1980), arguing that the focus on offender status was too confusing, redefined white-collar crimes as crimes of deception and as characterized by interest clashes between principals and agents. Pushed to its limits, this would mean that all white-collar crimes are organized fraud (though of course, not all organized crimes are fraud). According to the UN Transnational Organized Crime Convention, one needs three or more people acting together for some undefined period of time to constitute organized crime, so some large-scale elite as well as junior opportunist “wellorganized” frauds are not “organized crime” in this sense: if you are in charge of a large organization – business or political party – and people do what you tell them, you may not need active conspirators. In practice, as the Dutch

Organized Crime Monitor has shown, “organized fraud” can be a shorthand phrase for frauds committed by career criminals rather than by respectables (e.g., van Koppen et al. 2010): the very mindset that Sutherland was seeking to undermine in his analogy, which remains a powerful folk image because part of the apparent threat of “organized crime” is that everything an “organized criminal” does threatens “legitimate society” (whereas, by omission, whatever those who are not organized criminals do is less threatening to society). Hence, the regular references to organized criminals “infiltrating” or “corrupting” commerce. Indeed, the criminal careers of white-collar criminals are more uneven than one usually finds elsewhere (Piquero and Benson 2004). Measuring “organized fraud” involves two difficult components: measuring how much of different frauds there are and measuring what proportion of them are “organized” (and by what criteria this “organizedness” is to be judged). The settings for frauds influence and reflect networks, in the context of fraud opportunities and “capable guardians,” in the classical situational opportunity model.

Fundamentals Of Organizing Frauds

One way of thinking about how frauds are organized is to develop a process model. When analyzing the dynamics of particular crimes and/or criminal careers, these procedural elements can be broken down further into much more concrete steps, sometimes referred to as “crime scripts” (Morselli 2008).

The Organization Of Fraud: A Process Model

- See a situation as an opportunity for fraud.

- Obtain whatever finance/equipment/data needed for the crime.

- Find people willing and able to offend (if conspirators are needed, inside and/or outside the victim organization), preferably those who are controllable and reliable.

- Carry out offenses in domestic and/or overseas locations with or without physical presence in jurisdiction(s).

- Minimize immediate enforcement/operational risks. Especially if planning to repeat frauds, neutralize law enforcement by technical skill, by corruption, and/or by legal arbitrage between jurisdictions.

- Convert, where necessary (e.g., where goods rather than money are obtained on credit), the proceeds of crime into money or other usable assets.

- Spend as much of the proceeds as desired.

- Find people and places willing to store those proceeds the offenders wish to retain (and perhaps conceal their origin).

- Decide which available jurisdiction(s) offers the best balance between comfort and the risk of asset forfeiture/criminal justice sanctions.

There is also a personality dimension (van Duyne 2000): some people seek out opportunities to defraud and look for facilitators like accountants or lawyers, whereas others just take what comes opportunistically. Felson (2003) has sought to account for some variations between area crime rates as the product of “crime chemistry”: features of a setting that come together to foster crime, including the presence of likely offenders and suitable targets as well as the absence of capable guardianship against the offenses that would otherwise take place. Features relevant to crime levels also include three other “often-important elements”: “props that help produce or prevent a crime,” “camouflage that may help an offender avoid unwanted notice,” and “an audience that the offender wants either to impress or to intimidate” (Felson 2003). Although Felson did not have white-collar offenses in mind, one might consider the extent to which these constructs help comprehend aspects of fraud.

Those who are connected to “organized crime” may already have in place all the steps as part of their ongoing “criminal enterprise.” Criminal finance, some or all criminal personnel, or the “tools of crime” (from companies registered in “secrecy jurisdictions” to anonymous prepaid debit cards which can be used globally) may come from or go to another country, constituting “transnational” crimes, or else remain within one country. The exploitation of international regulatory and criminal justice asymmetries – for example, different levels of enforcement in the states or countries in which the fraudsters operate and victims are located – represents a positive advantage for fraud compared with most other property crimes.

Applying the sort of script found in the process model above, fraudsters seek potential victims for their schemes and develop techniques for getting them to part with their money voluntarily. In some cases, they or others may revictimize the same people by offering (for a fee) to help them get back the money they have lost. Another characteristic difference is that the offender and victim do not ever have to be in the same place at the same time. Some such offenses involve face to face contact throughout or at some stage; others are done wholly remotely, like lottery and eBay scams. An example of the latter is “419 frauds,” so called after section 419 of the Nigerian criminal code (explored in detail by Schoenmakers et al. 2009). Most e-mail users have received scam emails – which usually arrive from a Yahoo! Mail, Hotmail, or Gmail address – offering them vast wealth if only they will help their previously unacquainted banker/relative of a famous deceased corrupt dictator put their “dormant account” or “unknown to the authorities but at risk” money into their own account for 25–40 % of the “take” (often £/€/$25 billion or million). The victim is later persuaded to pay “advance fees” to remove blockages in the funds transfers and may even be lured to Nigeria, South Africa, or some other country to pay out more. Nigerians turn to their advantage the stereotype of their corruption in order to make the proposition more plausible to their intended targets. Alternatively, they make religious-type appeals – starting with “Dear Brother in Christ” – to assist orphans, or some other spoof rationale for large funds being available, such as money being left to the target in an unknown relative’s will.

Choice of offender or victim location is determined by convenience or by deliberate targeting by globally mobile offenders, though consumer frauds can be plotted from afar: see, e.g., Holtfreter et al. (2005, 2008). Businesspeople find it easy to transfer funds out of the company and/or to commit bankruptcy fraud, making relationships with organized crime groups usually unnecessary, though the latter may offer economies of scale and protection from the police or impose their will by threats of violence. The corporations can be substantive and real or they can be mere fronts or shells for the perpetration of fraud. But people can also commit frauds against companies and the government as outsiders or from more junior positions. Fraud permits a variety of offender organizational permutations, from Mafia-type associations to sole or small group offending.

As for the persistence of crime techniques over time, this varies depending on the countermeasures taken by potential preventers, who are mostly outside criminal justice. Fraudsters can now use payment card numbers skimmed from unsuspecting cardholders or hacked/copied from corporate databases to order hundreds of computers on the net from different suppliers, have them delivered to “drop addresses” in any credible country, and then forwarded to addresses elsewhere for resale: all of this before the cardholder or card issuer becomes aware that anything has happened to their card or account. This and other cyberfraud techniques reflect a comparative criminal advantage arising from the combination of high technological skills and high motivation because of poor opportunities in their home countries. There are also large-scale credit card and loan “bust outs” using stolen identities to obtain goods and money. Although these are often referred to as “identity theft,” they are more accurately referred to as identity duplication, since the original person is not deprived of their existing identity. The illustrations above show that behavior of victims-to-be and “capable guardians” has to be considered as part of the organization of crime. Nowadays, electronic credit histories are omnipresent in the UK and USA, but such data are less available elsewhere, especially in emerging economies where long business and individual commercial data do not exist. Even addresses in Africa are usually postbox numbers rather than physically identifiable dwellings. Many of the features upon which “identity validation” rests are not uniformly available, and this creates difficulties for legitimate people wanting to open bank or other credit accounts in the face of anti-money-laundering identification requirements developed for advanced economies.

Felson and Boba (2010) view white-collar crimes as “crimes of specialized access.” However, though useful, this is an inadequate compass for all frauds. Some frauds require professional licenses, some involving lengthy training, which “organized criminals” (in the conventional usage of that term) are ill-equipped to undertake in the short run. Thus, Italian-American Mafiosi who aspired to become “penny stock” fraudsters had to find people with licenses before they could diversify – fortunately for them, some Americans of Russian origin who had licenses were willing to assist them. But other frauds, like some credit card and insurance frauds, and even corporate bankruptcy frauds, do not require specialized access but are available to new entrants who have enough initiative and some basic skills, which have become greater as the introduction (outside the USA) of cards with chip and PINs has made it difficult to use stolen cards (see Forsyth and Castro (2007) for a professional credit card fraudster’s perspective). “Stealth frauds,” like the illegal downloading of personal information from data sets and using it for “identity fraud,” the copying of magnetic stripe data from credit cards, and illegal electronic funds transfers, may but do not always need specialized access. Shover et al. (2003) state that the sales agent in telemarketing scams generally works from a script that lays out successful sales approaches and responses. Promising contacts are turned over to a “closer,” a more experienced, and a better-paid sales agent. The hierarchy of the firms and the routine of turning prospects over to more experienced closers explain why victims typically report contact with multiple salespersons.

What factors influence the choice of venue for boiler room telemarketing frauds and their modus operandi? From UK cases examined by this author (see also http://www.cityoflondon.police.uk/ CityPolice/Departments/ECD/Fraud/boilerroom. htm), boiler rooms are commonly based abroad (e.g., in Spain, where police interest is low); never seek authorization by the regulator, the Financial Services Authority (FSA), which authorization is a legal requirement to sell securities in the UK; and use high-pressure sales and telephone techniques (author interviews with UK officials and police). One more sophisticated technique is to approach a small UK company not listed on the stock exchange and propose to raise capital by selling £100,000 worth of shares in that company on their behalf. Of this £100,000, the boiler room would agree to take 60 % as its fee, leaving the small company with £40,000 capital. In reality, the boiler room will “cold call” (i.e., telephone without prior contact) UK investors to sell the shares at up to 100 % over the agreed price, take their fee, and vanish. The small companies involved may become liable to refund investors the full price paid for their shares. There are several variations on the method of committing the crime:

- Complete con, where there are no shares in existence

- Different instruments used – stock, currency options (and even bull sperm)

- Restricted (e.g., US “Regulation S”), worthless, or overpriced shares

- Purported involvement in raising capital for companies

- Market manipulation where there are shares in existence and a (limited) market

- Deceptive share promotion via bulletin boards (For a broader examination, see Shover et al. 2003; Stevenson 2008.) If the fraudsters have sufficient nerve, they can seek to become regulated in one EU country and obtain a “passport” to operate in another under EU single market regulations, using that as a base for fraud and making it difficult for local regulators to intervene to close them down. In all of these cases, what the boiler room is really selling is deceptive and worthless expectations. Similar patterns exist in the USA (Tillman and Indergaard 2005), though within the USA interstate scams constitute federal offenses: hence, the preference of some fraudsters for operating from Canada.

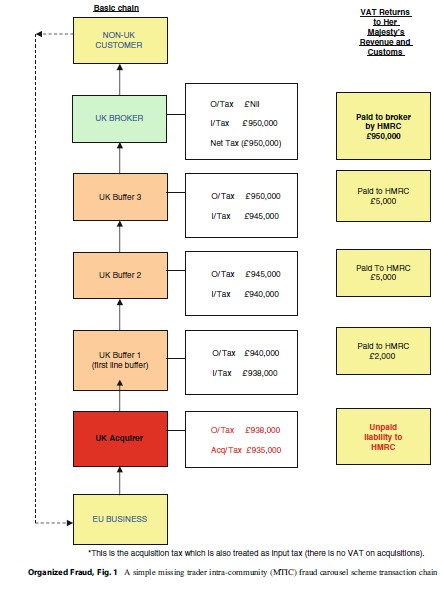

One common type of tax fraud in Europe is known as “carousel fraud.” This may involve any type of standard-rated goods or services. Goods or services are acquired zero-rated from the EU, with the acquirer then going missing without accounting for the value-added tax (VAT) due on the onward supply. However, in the case of a British scam, the goods or services do not become available in the UK for consumption, but are sold through a series of companies in the UK and then exported or dispatched, prompting a repayment from the government (HMRC) to the exporter/dispatcher. This process can be repeated over and over again using the same goods or commodities. When this happens, it is called “carousel fraud.” In some cases, no real products are traded at all but the transactions exist only on paper (Fig. 1).

Mortgage Frauds

The social construction of mortgage fraud is intriguing and has been relatively little researched (though see Nguyen and Pontell (2010), and their respondents and – for a quick summary – Black 2009). The FBI (2011) notes that its “perpetrators include licensed/registered and nonlicensed/registered mortgage brokers, lenders, appraisers, underwriters, accountants, real estate agents, settlement attorneys, land developers, investors, builders, bank account representatives, and trust account representatives. There have been numerous instances in which various organized criminal groups were involved in mortgage fraud activity. Asian, Balkan, Armenian, La Cosa Nostra, Russian, and Eurasian organized crime groups have been linked to various mortgage fraud schemes, such as short sale fraud and loan origination schemes.. ..Mortgage fraud perpetrators have been known to recruit ethnic community members as co-conspirators and victims to participate in mortgage loan origination fraud.” A later report (FBI 2012) gives a lucid overview of the process:

Fraud has been identified throughout the loan process, which commences with the borrower providing false information to the mortgage broker and/or lender. The next layer of potential fraud – the corporate fraud – occurs with the banks, brokerage houses, and other financial institutions that package loans through the securitization process. As the housing market declined, subprime lenders have been forced to buy back a number of nonperforming loans. Many of these subprime lenders have relied on a continuous increase in real estate values to allow the borrowers to refinance or sell their properties before going into default. However, based on the sales slowdown in the housing market, loan defaults increased, the secondary market for subprime securities dwindled, and the securities lost value. As a result, publicly traded stocks dramatically decreased in value as financial institutions realized large losses due to the subprime securities they held or insured, resulting in financial difficulties and bankruptcies.

Though the subprime securitization racketeering was a US specialty, mortgage fraud still appears easy to commit in the UK, by solicitors (UK lawyers) in collaboration with property buyers. In Legal Futures (2012), a foreign lawyer registered with the English regulators to work in a law firm was sentenced to 7 years in prison as being “at the helm of a criminal gang that defrauded high street banks out of almost £8 m by taking out mortgages on properties they did not own” and indeed for consequential money laundering. A Mr Younas, using an alias, was director of Montague Mason Solicitors:

He submitted false paperwork to Birmingham Midshires and Abbey banks in connection with 33 fraudulent mortgage applications in a two-month period in late 2008. His fellow gang members had previously identified suitable properties across the south-east to use for false mortgage applications – with the homeowners unaware of the crime. The fraudulent mortgages were finalised when false paperwork was completed by the solicitors, and signed by Younas, including the certificates of title requesting the banks release the funds. Once the deals were signed off and the funds transferred, the stolen money was quickly transferred from the solicitor’s account into a network of bank accounts, controlled by Younas and the rest of the gang. The money was then withdrawn in cash.

The regulators had already closed down Montague Mason in February 2009, and he was struck off the register of foreign lawyers in 2010, incapacitating him from crimes that involve authorized lawyers in the UK, provided that anyone checked the register. Middleton (2005) has critically examined responses to frauds by English lawyers.

It is possible to review the dynamics between setting and criminal act for identity and other frauds, such as application frauds and insurance frauds. In mortgage frauds, fraud typically takes two forms: customers lying about their own means – that is, exaggerating their income – and/or falsifying documents, such as creating fake payslips that show they earn an amount large enough to justify the mortgage they need, even if it is a multiple of their real income. This can be done simply by printing fake payslips, if necessary, on a color printer. Self-certificated mortgages (at higher interest rates in the UK) were allowed to cater for the increasing number of self-employed persons who could not produce genuine payslips; in the USA, the brokers simply filled some invented number in for them. One incentive for mortgage introducers is that they are paid commission; one incentive for lenders is that they have sales targets to hit and performance bonuses to get, and nonpayment usually comes much later. In some cases, the borrower is told there is no way they are going to get the mortgage they want with their income and that they should leave that part of the mortgage application form blank. After they have gone, the broker inserts the false income. In the USA particularly, there have been widespread scandals relating to commission-hungry brokers lying to purchasers about the affordability of mortgages, which they discover only when the initial low rates expire (Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission 2011). In other cases, the would-be purchaser colludes with the broker. In other cases still, the broker (or lawyer) purchases the properties for themselves as beneficial owner, using the names and real or fictitious income details of clients. In a rising market, where there is demand (e.g., from students) for rental properties, fraudulent purchasers see little downside risk. In some cases, professionals appointed by lending institutions are aware that the lenders need to lend, and their judgment is swayed by this to give the valuation required to enable the mortgage to be granted: this is especially so where all the parties’ desires are in the same direction (author interviews with surveyors, 1980s and 2008). However, when the market turns, as it did in 2007 (and earlier in the USA, where FBI warnings of a mortgage fraud epidemic went unheeded by politicians and regulators), these frauds are shaken out as people cannot keep up with repayments. (This was less common in Europe, though European banks – and later European taxpayers – ended up suffering because they purchased triple A-rated derivatives based on these nonperforming loans).

Fraud And Money Laundering

In any dataset of suspicious activity reports from banks, law firms, brokers, etc., a significant percentage of reports have “fraud” ticked as a reason for suspicion. Oftentimes, this is the product of hunch rather than specific knowledge, but there is so much confusing rhetoric about money laundering that I will try to bring some clarity here. There are in essence two definitions of money laundering. The first, more or less universalized following the success of the Financial Action Task Force in pressurizing countries around the world to legislate, is that anything that is done with the proceeds of crime to hide or store them becomes “laundering.” Thus, all proceeds of fraud that are not directly consumed in “lifestyle” are laundered. The second – which may correspond more closely to what people think laundering is – is that all proceeds of fraud that are sought to be legitimated as “clean money” are laundered. The difference between these two categories depends on how much effort is made and expected to be made by civil creditors and law enforcement to trace funds.

Many parties can be involved in laundering, but the number can be as low as one. This insider involvement is not uncommon for large-scale financial frauds: just as Cressey (1955) argued that all accountants could commit embezzlement, the fraudster has exactly the skills required to also conceal the sources of his funds. Where offenders start out with a business that is being used as a medium for what looks like legitimate activity – which is not the case for credit card fraudsters, for example – then placement of funds in banks may not attract suspicion: corporate lawyers may be falling over themselves to offer well-paid services in the construction of corporate vehicles. They will not routinely suspect senior corporate staff of being major criminals, perhaps especially since they were appointed by them and would like to be paid by them in the future. Since many frauds would be unsuccessful if they did not look like legitimate activity, this gives them a structural advantage over other types of offenders. On the other hand, if corporations are paying bribes to public servants to defraud their countries or to private purchasing officers to defraud their companies, then more subtle mechanisms for concealment may be necessary. Such conduct would seldom be associated with “organized crime” as conventionally defined, however. Surprisingly, little research has taken place (or has been commissioned by governments around the world) on how criminals generally, or fraudsters in particular, launder their funds. In recent years, the greatest attention has been paid to how the proceeds of grand corruption are laundered: but the overlap between fraud and corruption means that many of these cases are really cases of fraud against the governments that both the bribe payers and the bribe recipients are committing. For good studies of this process of laundering the proceeds of corruption, see de Willebois et al. (2011) and Sharman (2012).

Enron

In the last year at Enron Global Finance group, managers were sometimes handed a list of Enron assets and instructed to go out and sell some to the special-purpose vehicles. A manager would pick something, from a plant to stock to a piece of a start-up company, and then discuss the deal with a team of internal lawyers and auditors. A bank or other investor lent money to the newly created company to finance the purchase. The new company, in turn, paid the money to Enron. The use of an intermediary was to make the loan belong to the new company, not Enron, and thus not to count as a debt on Enron’s financial statement. Instead, it counted as income to Enron when the new company passed on the proceeds. Less debt and more income assured Enron would keep its high credit rating (making borrowing cheaper) and would keep the stock price up.

Top graduate school employees told the Houston Chronicle (20 January 2002) there were many uses for the vehicles that they considered legitimate, such as bringing in outside partners to share the risks of a particular venture: but there was little question, especially toward the end, that many had no real “business purpose” other than improving financial appearances. Say the asset was 100 shares of IBM stock. Enron would divide each share into two parts, one called a “control interest” and one called an “economic interest.” Then it would sell the economic interest to a newly created special-purpose vehicle. The asset was rarely as simple as 100 shares of another company’s stock. So Enron had to put a value on it. Because there was no real outside buyer, it decided the price itself and had that number approved by its auditor, Arthur Andersen.

The deal was placed with a bank, insurance company, or other major lender, which put up 97 % of the money. Sometimes the promise of Enron stock would be put up to guarantee the loan, although Enron stockholders were never told of the risk that their shares could be diluted if such new shares had to be issued. To qualify as “independent” from Enron for accounting purposes, a special-purpose vehicle had to be owned by someone else. So an outside entity would be brought in to make the required investment, perhaps a tiny percentage of the SPV’s total start-up cash, sometimes illicitly lent by Enron itself. An employee told the Houston Chronicle (20 January 2002):

Enron no longer owned the economic interest in the asset, but it did own control over it. In the sales contract with the vehicle, Enron promised always to act in the interest of the SPV. Lawyers and auditors said all this was OK. As the asset made money for the SPV – if it did, and many didn’t – it made principal and interest payments to the lender and issued dividends to the outside equity partners, just like in a normal company.

Enron got to report the proceeds of the sale of the asset as earnings. It had to repay the loan.. .but the debt didn’t show up on Enron’s financial statements.

“Investors don’t like to hear you say, ‘Oh, I was wrong.’ So you start having a yard sale to boost CFO (cash flow from operations) and net income,” the employee said.

As the Enron indictments showed, there were plenty of accountants, bankers, and lawyers as well as some senior management willing to participate in criminal or marginal operations. But they had nothing to do with any minority ethnic or national communities (except for White Anglo-Saxon Protestant Americans), nor with any criminal subcultures as conventionally defined. Likewise, the many works on the savings and loans “failures” (Black 2005; Calavita and Pontell 1993) and on accounting frauds (Tillman and Indergaard 2005) emphasize the culpable involvement of elite networks rather than marginal firms, whereas there is no reason why elite and marginal firms (plus “organized criminals”) cannot be involved in frauds and money laundering.

Conclusions

Globalization of fraud is affected by settings, with their rich and varied opportunities (reflecting patterns of business, consumer, and investment activities), the abilities of would-be perpetrators to recognize and act upon those opportunities (the “crime scripts” perspective), and their interactions with controls including law enforcement and formal regulation (touched only lightly upon here). Even in law enforcement circles (WEF 2012), the structure of groups is becoming less important than analyzing what people need from the largely illicit and largely licit worlds to go about the business of fraud. Such observations or claims about the contested and shifting nature of analysis over time complicate the already difficult question of whether fraud “itself” has changed over the years (Levi 2008a, b, 2012). It seems reasonable to reflect on two “historical” questions:

- In what respects has fraudulent activity changed, in terms of the sorts of techniques and organization that are or can be used, in relation to the efforts made (intentionally or not) to prevent frauds?

- In what respects has the world of fraud changed and what would the sort of people with the sort of skill sets/networks who committed frauds in the 1960s and 1970s have contemplated doing today?

In relation to the first question, although the basic techniques used by fraudsters 50 or even a hundred years ago are still available today, especially against those investors and trade creditors who make only modest enquiries, the professionalization of investor protection and credit management, interest by “consumer programs” on television and sections in newspapers, and websites and other electronic sources make the commission of such frauds harder. E-commerce, the growth of lightweight, high-value electronic products, and the technology of rapid delivery anywhere in the world have cut down decision times and opened up domestic and foreign markets to fraudsters operating within and from outside all developed economies. At the high end of insolvency frauds, however, it seems doubtful whether the more skillful abuses of insolvency by those who, for example, establish beneficially owned corporate fronts offshore and then create artificial debts to them which enable them to vote in friendly liquidators or administrators are any harder to commit or are any more likely to be punished today than they were 50 years earlier. Formal social control – the police and criminal courts – has not been particularly interested in frauds other than the more visibly harmful “widows and orphans” cases and those committed by gangsters, “professional criminals,” and terrorists in whom they already have an interest irrespective of the frauds they have committed. In Australia and Europe, and even in smaller jurisdictions such as Mauritius, pushed by international technical assistance, there has been a growth in “civil recovery” regimes, applying financial investigation and asset forfeiture (irrespective of criminal conviction) to supplement post-conviction confiscation remedies. However, even if they have substantial savings rather than (e.g., as did the high-spending bankruptcy fraudsters interviewed by Levi 2008a, and did the telemarketers interviewed by Shover et al. 2003) spending “their” proceeds as they went along, few fraudsters are high-profile career criminals of a seriousness level that would interest enforcement agencies specializing in combating “organized crime.” This question is connected to the second.

The dominant mode of thinking about serious crime for gain has been the “rational choice” model implicit not only in the economic analysis of crime but also in situational crime prevention “theory” (see Schuchter and Levi 2013). The selection of fraud in general or particular forms thereof in particular depends on the confidence, skills, and contact set of any given individual offenders. The presence or absence of “crime networks” known to and trusted by the willing offender makes a difference to “crime capacitation”: an issue often neglected in individualized explanations of involvement in crime. Choice of crime type might also be affected by age. Those offenders who were in their 50s and over might be deterred by the technological challenges of cyber activities, and the age gap might apply to co-criminality as it does to other feature of contemporary life. So today’s new generation fraudsters might gravitate toward more hi-tech forms of fraud, whereas if they were in late career, it might seem too risky to adapt in unfamiliar territory unless they can find someone younger to collaborate with. Some fraudsters display a remarkable aptitude for creativity and constant testing out of commercial systems and private individuals for signs of weakness. This focus on “criminal transferrable skills” – the set of aptitudes including social networking that individual/sets of offenders have – concentrates our attention on offender creativity, energy and social networking skills in finding co-offenders (or “turning” nonoffenders into co-offenders), and in adapting techniques: many offenders (and non-offenders) lack one or all of these qualities.

With only modest sophistication, the Internet has made it easier for foreign natural and legal persons to defraud consumers and suppliers, for example, via counterfeited or cloned payment cards. Fraudsters could be involved in the theft of personal data from garbage (“bin raiding”) or by hacking into data storage facilities; or they could simply send “phishing” emails offering academics invitations to conferences on “child protection and the economic crisis” to try to con them into giving their personal details for the free visa and transport arrangements that will later turn out to be illusory. They could also be involved in account manipulation by insiders, whether in call centers or elsewhere. (The offshoring of call centers led to periodic media alarm stories about blackmail and corruption in India: but it is nonsensical to think that this cannot happen in the developed world, with badly paid, high turnover staff ratios. Indeed, there may be tougher regimes in Indian call centers – staff searches and prohibitions on mobile phones – than might be allowed in Europe.) Rings of staged accidents with claims for hard-to-falsify personal injuries would be within the skill set of many (once they worked out what to do), as would organized benefit fraud and – especially – the sale of counterfeit products, whose quality digital technology has done so much to improve. For the more adventurous, scams can involve some currently fashionable musical or sporting events, or the

Muslim Hajj, or a social cause such as “renewable energy” or commercialized carbon trading. The underlying concepts were available to investors centuries ago, at the time of the South Sea Bubble or the Dutch Tulip Mania, but every generation has to learn the lessons for itself. When times get hard, people may take more risks to avoid downward mobility; when times are good, everyone wants to get onto a rising bandwagon. Both circumstances offer opportunities to fraudsters.

Bibliography:

- Black W (2005) The best way to rob a bank is to own one. University of Texas Press, Austin

- Black W (2009) The two documents everyone should read to better understand the crisis. http://www. huffingtonpost.com/william-k-black/the-two-documentseveryon_b_169813.html. Accessed 11 March 2013

- Calavita K, Pontell H (1993) Savings and loan fraud as organized crime: toward a conceptual typology of corporate illegality. Criminology 31(4):519–548

- Cressey D (1955) Other people’s money. Free Press, New York

- de Willebois, van der Does E, Emily H, Robert H, Ji Won P, Jason S (2011) The puppet masters: how the corrupt use legal structures to hide stolen assets and what to do about it. World Bank, Washington, DC

- FBI (2011) 2010 Mortgage fraud report: year in review. FBI, Washington, DC

- FBI (2012) Financial crimes report to the public. FBI, Washington, DC

- Felson M (2003) The process of co-offending. In: Smith MJ, Cronish DB (eds) Theory for practice in situational crime prevention. Criminal Justice Press, Monsey, pp 149–167

- Felson M, Boba Santos R (2010) Crime and everyday life. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

- Forsyth N, Castro E (2007) Other people’s money: the rise and fall of Britain’s boldest credit card fraudster. London, Panv

- Holtfreter K, Van Slyke S, Blomberg T (2005) Sociolegal change in consumer fraud: from victim-offender interactions to global networks. Crime Law Soc Chang 44(3):251–275

- Holtfreter K, Reisig M, Pratt T (2008) Low self-control, routine activities and fraud victimization. Criminology 46(1):189–220

- Legal Futures (2012) Struck-off lawyer jailed for £8m mortgage fraud. http://www.legalfutures.co.uk/ latest-news/struck-off-lawyer-jailed-for-mortgage-fraud. Accessed 11 March 2013

- Levi M (2008a) The phantom capitalists: the organisation and control of long-firm fraud, 2nd edn. Ashgate, Aldershot

- Levi M (2008b) Organised fraud: unpacking research on networks and organisation. Criminol Crim Justice 8(4):389–420

- Levi M (2012) Trends and costs of fraud. In: Doig A (ed) Fraud: the counter fraud practitioner’s handbook. Gower Publishing, Andover, pp 7–18

- Middleton D (2005) The legal and regulatory response to solicitors involved in serious fraud. Br J Criminol 45(6):810–836

- Morselli C (2008) Inside criminal networks. Springer, New York

- Nguyen, Pontell (2010) Nguyen, TH and HN Pontell, Mortgage origination fraud and the global economic crisis: a criminological analysis. Criminology and Public Policy 9(3)591–612

- Piquero NL, Benson M (2004) White-collar crime and criminal careers: specifying a trajectory of punctuated situational offending. J Contemp Crim Justice 20(2):148–165

- Schoenmakers Y, de Vries Robbe´ E, van Wijk A (2009) Mountains of gold: an exploratory research on Nigerian 419-fraud. SWP, Amsterdam

- Schuchter A, Levi M (2013) The Fraud Triangle revisited Security Journal, 2013/02/04/online doi:10.1057/ sj.2013.1

- Sharman J (2012) Chasing kleptocrats’ loot: narrowing the effectiveness gap. Chr. Michelsen Institute, Bergen, U4 issue August 4

- Shapiro SP (1980) Collaring the crime, not the criminal: Reconsidering the concept of whitecollar crime. American Sociological Review 1990;55 (3):346–65

- Shover N, Coffey GS, Hobbs D (2003) Crime on the line: telemarketing and the changing nature of professional crime. Br J Criminol 43(July):489–505

- Stevenson R (1998) The boiler room and other telephone sales scams. University of Illinois Press, Urbana

- Stevenson RJ (2000) Boiler room and other telephone sales scams. University of Illinois Press, Champaign, Il

- Sutherland E (1945) Is “white collar crime” crime? Am Sociol Rev 10(2):132–139

- Sutherland E (1985) White-collar crime: the uncut version. Yale University Press, Princeton

- Tillman R, Indergaard M (2005) Pump and dump: the rancid rules of the new economy. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick

- van Duyne P (2000) Mobsters are human too: behavioural science and organised crime investigation. Crime Law Soc Chang 34:369–390

- van Koppen M, de Poot C, Blokland A (2010) Comparing criminal careers of organized crime offenders and general offenders. Eur J Criminol 7(5):356–374

- WEF (2012) Organized crime enablers. World Economic Forum, Geneva, http://www.weforum.org/reports/ organized-crime-enablers. Accessed 11 March 2013

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.