This sample Public Defenders Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

The United States Constitution guarantees the right to be represented by attorney to every person accused of a crime whose life or liberty is at stake. When a defendant cannot afford to hire his own attorney, the government is obligated to provide him not merely with token representation but with effective assistance of counsel. In recent years, indigent defense systems have been characterized as overloaded, and the constitutional promise of effective legal representation for the poor in state courts has been perceived as “broken” (Justice Policy Institute 2011; American Bar Association 2004). Among the primary challenges are excessive caseloads and a lack of adequate funding for defense services. In order to function properly, the adversarial system used in American courts relies upon the presence of capable counsel for both the state and the accused. Without appropriate resources, the ability of the defense attorney to provide effective assistance of counsel is compromised, jeopardizing the constitutional rights of the accused and the integrity of the criminal justice system. According to former US Attorney General Janet Reno, “[i]ndigent defense is an equally essential element of the criminal justice process, one which should be appropriately structured and funded and operating with effective standards. When the conviction of a defendant is challenged on the basis of inadequate representation, the very legitimacy of the conviction itself is called into question. Our criminal justice system is interdependent: if one leg of the system is weaker than the others, the whole system will ultimately falter” (American Bar Association 2004). This research paper explores the constitutional foundations of the right to counsel, provides an overview of the various means by which states provide indigent defense services, outlines the numerous tasks and functions that public defender attorneys and staff must perform in order to provide effective assistance of counsel, and examines the implications of an underfunded indigent defense system.

The Right To Counsel

The Sixth Amendment of the United States Constitution provides that “[i]n all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right … to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defence.” Until the middle of the twentieth century, the Sixth Amendment was held to apply only to the federal government, not to the states, and was interpreted to require the government only to allow the defendant to hire his own lawyer, not to appoint one for him. A number of states did provide counsel in certain cases, either by statute or by virtue of a right created under the state constitution, but the appointment of counsel was typically limited to capital cases (Wice 2005).

In 1932, the Supreme Court held for the first time that a state government was obligated to provide the defendant with counsel in a capital case. Basing its decision upon the Fourteenth Amendment right to due process of law rather than the right to counsel enumerated in the Sixth Amendment, the Court explained that

The right to be heard would be, in many cases, of little avail if it did not comprehend the right to be heard by counsel. Even the intelligent and educated layman has small and sometimes no skill in the science of law. He lacks both the skill and knowledge adequately to prepare his defense, even though he had a perfect one. He requires the guiding hand of counsel at every step in the proceedings against him. Without it, though he be not guilty, he faces the danger of conviction because he does not know how to establish his innocence. (Powell v. Alabama 1932)

The Powell v. Alabama decision recognized a defendant’s right to appointed counsel only in capital cases tried in state courts. In 1938, the Supreme Court held that the Sixth Amendment required the federal government to provide counsel for a defendant facing federal noncapital felony charges who was unable to obtain counsel on his own, unless the defendant had “intelligently waived” the right to counsel (Johnson v. Zerbst 1938). Just four years later, however, the court in Betts v. Brady declined to require states to appoint counsel in all noncapital felony cases, finding that the Sixth Amendment right to counsel was not a “fundamental right” that applied against the states through the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment (Betts v. Brady 1942).

In 1963, the Supreme Court overturned Betts v. Brady in the case of Gideon v. Wainwright, finally recognizing a right to appointed counsel in all felony cases prosecuted in state courts. The state of Florida had charged Clarence Earl Gideon with the felony offense of breaking and entering a poolroom with intent to commit a misdemeanor. Unable to afford an attorney, Gideon asked the trial court to appoint one for him. The court denied his request, and after representing himself at trial, Gideon was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison. Gideon petitioned the Florida Supreme Court for a writ of habeas corpus, claiming that his conviction violated his rights under the US Constitution. After the Florida Supreme Court denied relief, Gideon appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States, which agreed to hear his claim and appointed a prominent attorney to represent him on the appeal. The Court went on to hold that the Sixth Amendment right to appointed counsel was indeed fundamental in nature and thus applied against the states under the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process clause, declaring it an “obvious truth” that “in our adversary system of criminal justice, any person haled into court, who is too poor to hire a lawyer, cannot be assured a fair trial unless counsel is provided for him” (Gideon v. Wainwright 1963).

Following its decision in Gideon, the Supreme Court interpreted the right to appointed counsel to apply in juvenile delinquency proceedings (In re Gault 1967) and in misdemeanor cases in which a sentence of incarceration is actually imposed (Argersinger v. Hamlin 1972). The Sixth Amendment right to counsel attaches at “a criminal defendant’s initial appearance before a judicial officer, where he learns the charges against him and his liberty is subject to restriction,” and counsel must be provided “during any ‘critical stage’ of the post-attachment proceedings” Rothgery v. Gillespie County (2008). The Supreme Court has also interpreted the Fourteenth Amendment to require the appointment of counsel for a defendant’s first appeal as of right, as well as for a discretionary appeal by a defendant who has pled guilty (Douglas v. California 1963; Halbert v. Michigan 2005). Finally, the court has held that the due process and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment require the state to furnish an indigent defendant with expert witnesses relevant to material issues (Ake v. Oklahoma 1985).

The mere fact that an attorney appears on behalf of the defendant is not sufficient to fulfill the Sixth Amendment right to counsel. When a defendant cannot afford to hire his own attorney, the government is obligated to provide him not just with counsel but with effective assistance of counsel. Effective assistance of counsel requires that the attorney exercise reasonable professional judgment under the circumstances of the case (Strickland v. Washington 1984). Attorneys in every state are also bound to abide by the state’s rules of professional conduct. Many states pattern their ethical rules for attorneys on the American Bar Association’s Model Rules of Professional Conduct, which require the attorney to provide “competent” and “diligent” representation to every client. These requirements include a responsibility to control the lawyer’s workload “so that each matter can be handled competently.” The attorney must also promptly communicate with the client regarding significant developments in the case, such as the prosecution’s offer of a plea bargain, and meaningfully involve the client in decision-making regarding the case (American Bar Association 2007). The American Bar Association’s Standards For Criminal Justice: Defense Function, although not binding upon attorneys, also establish norms for the performance of defense attorneys. Standard 4-1.3(e) specifies that “[d]efense counsel should not carry a workload that, by reason of excessive size, interferes with the rendering of quality representation, endangers the client’s interest in the speedy disposition of charges, or may lead to the breach of professional obligations.” The standards also set expectations for the defense attorney’s performance in specific activities such as investigating the facts of the case and exploring the possibility of disposition without trial.

Indigent Defense Systems

An indigent defendant may be represented by an attorney from a public defender’s office, assigned counsel, or a contract attorney. In a public defender program, salaried attorneys represent the majority of indigent defendants within a jurisdiction. Public defender offices exist primarily in larger communities, and public defender attorneys typically work together in a central office that is headed by a director and supported by additional staff (Wice 2005). Public defenders may be government employees, and the public defender office may be an independent nonprofit agency such as the Legal Aid Society of New York. In smaller jurisdictions, a system of assigned counsel is typically used. Under this model, private attorneys are selected from a list, either formal or informal, to take cases and are paid either by the case or by the hour (Lefstein and Spangenberg 2009). Many states cap the fees or hours an attorney may bill per case; some states allow judges to waive these caps upon request, but others do not. Roughly 2,800 out of 3,100 counties in the United States rely exclusively on assigned counsel to provide indigent defense services (Wice). Jurisdictions with public defender offices also use assigned counsel in cases involving conflicts of interest, such as those with multiple defendants. Finally, under the contract model, private attorneys bid to provide representation for all or a percentage of indigent defendants in a particular jurisdiction. Contract attorneys may be paid a flat fee to accept all assigned defendants or may be paid according to their caseload.

Indigent defense systems are paid for by state governments, local governments, or a combination of both. As of fiscal year 2008, indigent defense services in 30 states were supported primarily or entirely through state funds; these states include Florida, Maryland, Missouri, New Hampshire, New Mexico, and Virginia. Indigent defense systems in 18 states (including Alabama, California, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, New York, and Texas) rely on counties for more than half of their funding; in Utah and Pennsylvania, indigent defense services are funded entirely by county governments (Lefstein and Spangenberg 2009). Countyfunded systems have been criticized because they create the potential for varying levels of funding, access, and quality depending upon where a defendant lives (Justice Policy Institute 2011).

Public Defender Tasks And Functions

The popular image of a criminal attorney centers upon the exchange of evidence and arguments in the confines of the courtroom. On one side is the prosecution; on the other, the defense. Each attorney calls witnesses, presents evidence to the judge and jury, and summarizes the case in closing arguments. For attorneys who represent indigent defendants, however, the popular view of the role of a criminal attorney is extremely myopic. Instead, the work of the defense team extends well beyond the courtroom, with defenders alternately wearing the hats of investigator, social worker, appellate attorney, and litigator.

Recent work by the National Center for State Courts highlights the diverse set of case-related and non-case-related tasks and functions that indigent defense attorneys and their support staff perform (Kleiman and Lee 2010; Steelman et al. 2007; Ostrom et al. 2005). Case-related activities include all tasks and functions directly associated with the handling of individual cases, from the time of appointment through post-trial and appellate activity. Both attorneys and staff must also devote time to certain core activities that are not directly related to a particular case, such as continuing legal education, attending training and conferences, and handling administrative matters such as budgets and personnel issues, community outreach, and staff meetings.

Attorney Activities

The basic case-related duties and responsibilities of defense attorneys can be sorted into a series of complementary functional areas. The first function is pretrial activities and hearings. This function encompasses all of the in-court and out-ofcourt work associated with pretrial proceedings, including legal research, preparation, participation in pretrial hearings, and drafting and arguing pretrial motions. Attorneys prepare for and participate in a host of bond and detention hearings, arraignments, pretrial conferences, status conferences, competency hearings, motion hearings, and other pretrial hearings. Additionally, defense attorneys are responsible for preparing and arguing motions regarding the evidence to be used at trial (e.g., motions to suppress, motions in limine) and motions for funds to secure expert witnesses. A second critical function of the defense attorney is negotiating plea alternatives with the prosecution. More than 90 % of criminal cases are resolved without trial through plea bargaining. In most cases, the defendant agrees to plead guilty in exchange for a reduction of the charges or sentence; other cases are resolved without a conviction through programs such as diversion.

A crucial – and often time-consuming – function for defense attorneys is client contact. The American Bar Association’s Ten Principles of a Public Defense Delivery Service assert that high-quality delivery of public defense necessitates that “counsel is provided sufficient time and a confidential space within which to meet with the client.” The defense attorney is obligated to inform the client of his or her rights at the earliest opportunity, build a rapport with the client that instills trust and confidence, and interview the client about the events associated with the charges. Attorneys are also responsible for keeping the client informed of case developments, responding to all client correspondence and inquiries, promptly explaining proposed plea bargains, and engaging the client in meaningful plea discussions. It is not unusual for an attorney to spend part of each day responding to numerous messages from clients calling to inquire about hearing dates and case status. Meeting with incustody clients can be especially time-consuming, as the attorney must travel to the jail, contend with security procedures, and wait for the client to be produced.

In order to provide an effective defense, public defenders must perform investigative and discovery activities. Attorneys are responsible for directing the activities of investigative staff, visiting the crime scene, and, when necessary, conferring with social workers and independent experts (e.g., forensic experts). Attorneys are also responsible for interacting with the prosecution regarding discovery and for preparing and submitting discovery requests. In short-staffed offices, attorneys often perform duties that could otherwise be handled by nonattorney investigative staff. These include reviewing audio and video recordings of hearings and interviews, interviewing prosecution and defense witnesses, visiting the crime scene to take measurements and photographs, preparing summary reports of investigations, and serving witness subpoenas.

A more “traditional” function of the defense attorney is participating in bench and jury trials. In addition to in-court work, trials may require a substantial amount of out-of-court preparation. Trial-related activities include preparing for and participating in jury selection, drafting proposed jury instructions, preparing and presenting the opening statement, cross-examining prosecution witnesses, and preparing and presenting the defense case and closing argument. Following a guilty verdict at trial, the defense attorney is responsible for sentencing and post-trial activities, including activities related to sentencing, post-trial motions, probation violations, appeals, and collateral proceedings such as petitions for habeas corpus. Specific post-conviction tasks include researching and preparing post-trial motions (e.g., motion for new trial), reviewing presentence reports, sentencing memoranda and the defendant’s social history, addressing the admissibility of the prosecution’s sentencing evidence, preparing for sentencing hearings, reviewing and correcting sentencing orders, investigating the circumstances surrounding probation violations, and preparing for probation revocation hearings. Tasks related to appeals and collateral proceedings include preparing petitions and briefs, reviewing the trial record, legal research, and preparing for oral arguments. Appeals and collateral proceedings may be handled by the attorney or office that originally represented the defendant at trial or by an attorney or office specializing in appellate work.

Finally, some attorneys are responsible for social work/sentencing advocacy tasks. Such tasks include identifying alternative sanction options; finding program placements; compiling the defendant’s medical, educational, and family history; and coordinating mental health evaluations and reviews.

Staff Activities

Effective assistance of counsel depends on the combined work of a defense team comprising both attorneys and non-attorney support staff. Public defender staff efficiently and cost-effectively perform many functions integral to the effective assistance of counsel, from investigating the facts of the case to locating alternative placement options to maintaining complete and accurate case files. Without sufficient support staff resources, public defenders’ ability to provide competent and diligent representation to indigent clients may be seriously compromised. Inadequate staff support also reduces the efficiency of the public defender office, as attorneys are forced to take time away from legal work to answer telephones, type documents, and maintain case files themselves.

Support staff tasks can be classified into two broad categories. The first set of staff functions is administrative in nature and includes activities such as client intake, records management, and secretarial services. Client intake includes tasks such preparing file folders, verifying claims of indigency, handling intake paperwork, scheduling initial client appointments, identifying potential conflicts of interest, and obtaining charging documents from court files. Records management includes entering data into case management systems, archiving and retrieving files, and handling billing for contract attorneys. Finally, secretarial services include tasks such as taking telephone messages, managing attorneys’ calendars, typing documents such as motions and subpoenas, and transcribing witness interviews.

The second category of support staff functions consists of professional and paraprofessional tasks directly associated with the facilitation of legal representation, including investigative services, legal research, direct attorney support, and social work/sentencing advocacy. Investigative services are typically performed by an investigator who is responsible for locating and interviewing defense and prosecution witnesses, reviewing the offense report and discovery package, visiting the crime scene to take measurements and photos, viewing and obtaining evidence, preparing summary reports of investigations, and testifying in court when necessary. Legal research is a function typically handled by a legally trained staff member, such as a paralegal, who reviews case files to identify legal issues, prepares legal memoranda, and performs legal research related to procedural and evidentiary issues. Direct attorney support includes in-court and out-of-court activities that provide the attorney with logistical support. Out of court, staff locate clients (e.g., identifying the jail in which a defendant is being held) and determine whether a client is a defendant in other criminal proceedings in the current jurisdiction or in other jurisdictions. Staff members also provide direct support to attorneys in the courtroom during all types of court proceedings, such as arraignments, bail reviews, preliminary hearings, motion hearings, trials, and sentencing hearings.

Finally, a specialized group of support staff provide defense attorneys with information related to a client’s medical, psychiatric, educational, and family history. Social work/sentencing advocacy staff develop mitigating information for sentencing, match defendants with appropriate drug treatment programs and other alternatives to incarceration, investigate the facts surrounding probation violations, coordinate witness appearances, and directly assist defendants with matters such as jail issues and obtaining legal identification.

Caseload Standards

To ensure that public defenders are able to fulfill their constitutional obligation to provide effective assistance of counsel, a set of national caseload standards were developed in 1973. Caseload standards are important because public defenders do not exercise direct control over the number of defendants they are assigned to represent and therefore the amount of work for which they are responsible. The National Legal Aid & Defender Association (NLADA) points out that public defender workloads “rise or fall due to a convergence of societal trends and decisions made by legislatures, police departments and prosecutors which are completely beyond the control of indigent defense providers” (NLADA 2008). ABA Principle 5 proclaims that national caseload standards should not be exceeded, and the workload of an attorney “should never be so large as to interfere with the rendering of quality representation or lead to the breach of ethical obligations, and counsel is obligated to decline appointments above such levels.”

Developed in 1973 by the National Advisory Commission on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals, the existing national caseload standards represent the maximum number of cases that a defense attorney should handle in a year, assuming that the attorney handles only a single case type. The commission recommended that caseloads should not exceed 150 felonies, 400 misdemeanors (excluding traffic), 200 juvenile court cases, 200 Mental Health Act cases, or 25 appeals per attorney per year. In recent years, several states, including Virginia, Maryland, and New Mexico, have developed their own state-specific caseload standards for attorneys and support staff in public defender offices. These efforts have been undertaken in response to the perceived limitations of the 1973 national caseload standards. Criticisms of the existing standards include the facts that the standards were not founded upon empirical research, do not allow for the varying complexity of different felony case types (e.g., homicide, violent felonies, and nonviolent felonies), do not capture the variability between states in criminal justice procedures and practices, and predate the introduction of information technology resources commonly used by today’s attorneys and support staff. Furthermore, the standards are silent on the level of staff support attorneys require in order to provide effective representation.

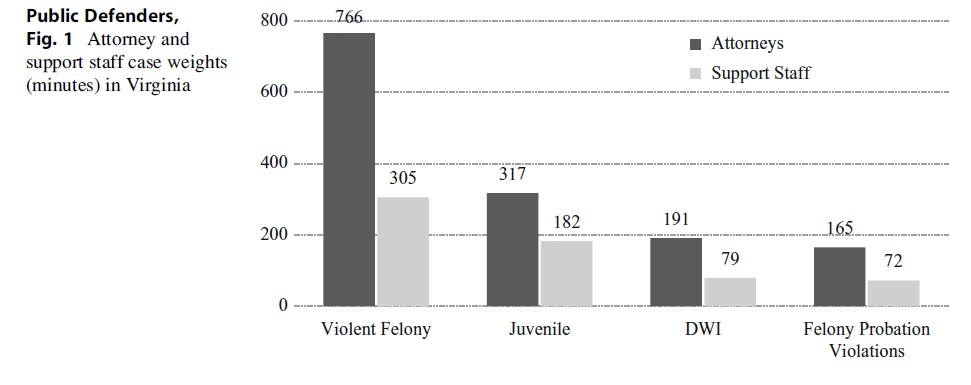

The new state-specific standards are expressed as case weights, which represent the average amount of time needed for an attorney or staff member to handle effectively each case of a particular type, from appointment through post-disposition activity. Separate case weights are calculated for different types of cases of varying levels of complexity (e.g., homicide, violent felony, misdemeanor, driving under the influence of alcohol, juvenile delinquency). For example, in Virginia, a violent felony case requires, on average, 766 minutes (12.8 hours) of hands-on attorney time and 305 minutes (5.1 hours) of staff time from appointment through post-disposition activity. In comparison, a nonviolent felony case in Virginia requires, on average, 433 minutes (7.2 hours) of attorney time. Case weights are typically constructed from empirical data collected during a “time study” that measures current practice, then reviewed by panels of expert attorneys and support staff to ensure that the weights allow sufficient time to provide effective representation. The case weights can be used in combination with caseload data to calculate total attorney and staff workload for a public defender’s office, along with the number of attorneys and support staff members needed to handle this workload effectively.

An Example From Virginia

Figure 1 displays a subset of the case weights developed for public defender offices in Virginia in 2010. Each case weight represents the average number of minutes of attorney or staff time required to defend one case of the specified type. Figure 1 illustrates two important concepts about the nature of public defense cases. First, cases handled by public defenders vary in complexity, as measured by the amount of attorney and staff time needed to provide effective assistance of counsel. For example, an average violent felony case requires twice as much attorney time as a juvenile case and four times as much as a DWI case or a felony probation violation.

Second, effective assistance of counsel requires the combined efforts of attorneys and support staff. For example, a typical juvenile case requires approximately 5 h of attorney time and 3 h of staff time.

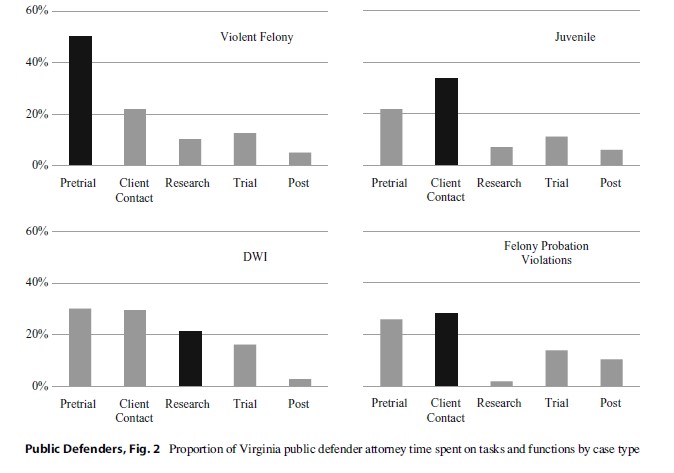

Figure 2 illustrates a third important concept: the relative amount of time attorneys (and staff) devote to different tasks and functions varies dramatically among case types. For example, in Virginia, approximately one-half of the attorney work required to defend violent felony cases is expended on pretrial proceedings, investigation, discovery, and plea negotiations. This results from factors such as the large amount of evidence typically associated with violent crimes and the complexity of plea negotiations in these high-stake cases. In felony probation violation cases, the largest share of attorney time is devoted to contact with the client and the client’s family. In DWI cases, on the other hand, a larger proportion of time is spent on legal research.

Implications Of Excessive Caseloads

The Washington Public Defender Association asserts that “caseload levels are the single biggest predictor of the quality of public defense representation. Not even the most able and industrious lawyers can provide effective representation when their workloads are unmanageable. A warm body with a law degree, able to affix his or her name to a plea agreement, is not an acceptable substitute for the effective advocate envisioned when the Supreme Court extended the right to counsel to all persons facing incarceration.” Similarly, a recent report by the Justice Policy Institute argues that “[p]roper resources and adequate time may not guarantee that every public defender will provide quality representation, but high caseloads and limited resources almost guarantee that this will not happen for all clients” (Justice Policy Institute 2011). In many jurisdictions across the nation, excessive caseloads currently jeopardize the quality of indigent defense services (Lefstein 2011). For example, in 2006, public defenders in Clark County, Nevada, had average per-attorney caseloads of 364 felony and gross misdemeanor cases (Lefstein and Spangenberg 2009). Although this figure includes felonies and excludes less serious misdemeanor cases, it is much closer to the 1973 recommendation for misdemeanor-only caseloads (400 per attorney per year) than the corresponding recommendation for felony caseloads (150 per attorney per year). Similarly, a recent census of public defender offices by the Bureau of Justice Statistics found that 15 state programs exceeded the 1973 recommendations for the maximum numbers of felony and misdemeanor cases per attorney (Langton and Farole 2010). Resource constraints have been exacerbated by the recent fiscal crisis, which has resulted in attorney and staff reductions for many public defender systems. For example, the Minnesota Board of Public Defense cut 15 % of its attorney positions in 2008 in response to budget shortfalls. Similarly, the Maryland Office of the Public Defender has recently reduced its workforce by nearly 20 % due to budget cuts (DeWolfe 2011).

Faced with excessive caseloads, public defenders are often forced to adopt a “triage” approach, rationing their time and focusing scarce resources on the most serious or urgent matters. Under such conditions, attorneys may not have sufficient time or opportunity to enter an appearance promptly during the critical early stages of the case, prepare thoroughly for all proceedings, communicate directly and in a timely manner with the accused, fully interview the accused and other witnesses to explore pertinent facts in a case, conduct a thorough investigation of all relevant facts and circumstances in each case, duly focus on each case and provide effective representation at trial, and prepare for and meaningfully participate in the sentencing process (Ostrom, Kleiman, Ryan).

ABA Principle 8 articulates the need for “parity between defense counsel and the prosecution with respect to resources.” Without sufficient resources to effectively handle indigent defense caseloads, guarantees of a fair and balanced adversarial process are compromised, with significant costs for individuals, the criminal justice system, and society as a whole. First, the failure to provide effective assistance of counsel can result in the unnecessary imprisonment of innocent defendants or in the imposition of unduly long prison sentences due to errors in scoring sentencing guidelines or failure to present mitigating evidence. The Justice Policy Institute proclaims that “[w]ithout a functioning adversarial justice system, everyday human error is more likely to go undiscovered and result in the tragedy of innocent people being tried, convicted and imprisoned” (American Bar Association 2004). Erroneous convictions and excessive sentences impose extra costs on taxpayers and the criminal justice system in terms of additional jail and prison bed days. Unnecessary incarceration is profoundly disruptive not only to the defendant himself but to his family and employer as well. A wrongful conviction also leaves the true perpetrator free to commit additional crimes, with corresponding societal costs. Second, ineffective assistance of counsel can lead to an increase in the number of appeals and post-judgment challenges to convictions, resulting in increased costs to the criminal justice system (Williams and Bost 1971). Third, when the defense attorney has insufficient time to prepare for and appear at court proceedings early in the life of a case (e.g., bail review hearing, arraignment), the defendant may remain in pretrial detention longer than necessary, or the opportunity for an early resolution of the case may be lost, resulting in increased jail, attorney, and court system expenditures. Finally, a lack of quality representation for indigent defendants can adversely impact perceptions of fairness and public trust and confidence in the criminal justice system. The National Legal Aid & Defender Association states that “public confidence in the integrity of the system is lost when the community perceives that inadequate representation creates a system that metes out justice differently to the rich and the poor” (NLADA 2004). It is not only high-profile reversals of wrongful convictions that can undermine public opinion regarding the quality of indigent defense; damage is also done when defendants, their families, jurors, and other participants in the criminal justice process perceive indigent defense attorneys to be overworked, ill prepared, or unresponsive to the needs and concerns of individual defendants.

Conclusion

Public defenders and other attorneys who represent indigent criminal defendants are essential to the due process of law in our nation’s criminal courts. The effective delivery of indigent defense services requires the joint effort of attorneys and support staff, whose work extends well beyond the confines of the courtroom. Recent studies have echoed a growing concern that “[t]he defender systems that people must turn to are too often completely overwhelmed; many dedicated defenders simply have too many cases, too little time and too few resources to provide quality or even adequate legal representation” (Justice Policy Institute 2011). In his 2005 State of the Judiciary address, former New Mexico Chief Justice Richard Bosson observed that “the fiscal needs of the [New Mexico] Public Defender are so dire, their situation seems so hopeless, that many times prosecutions cannot go forward due to lack of sufficient personnel.” Chief Justice Bosson went on to describe the criminal justice system with the oft-used metaphor of the “threelegged stool” supported by the prosecution, the defense, and the court: “When one leg is weakened, you know what happens; you end up on the floor. Well, we are not on the floor yet, but we are not far off.” As the current fiscal crisis threatens further reductions to already strained budgets for indigent defense services, the threelegged stool is wobbling more visibly in many states across the nation. Empirically based workload standards for public defenders can help to ensure that caseloads are manageable, enabling attorneys to make good on the constitutional guarantee of effective assistance of counsel and helping to preserve the integrity of the criminal justice system.

Bibliography:

- Ake v. Oklahoma (1985) 470 US 68

- American Bar Association Standing Committee on Legal Aid and Indigent Defendants (2004) Gideon’s broken promise: America’s continuing quest for equal justice. American Bar Association, Chicago

- American Bar Association (2007) Model Rules of Professional Conduct, Chicago, IL

- Argersinger v. Hamlin (1972) 407 US 25

- Betts v. Brady (1942) 316 US 455 472

- Criminal Justice Standards Committee American Bar Association (1993) ABA standards for criminal justice: def funct 3rd Edn, Chicago, IL

- Davies ALB, Worden AP (2009) State politics and the right to counsel: a comparative analysis. Law Soc Rev 43:187–220

- DeWolfe PB (2011) Fiscal year 2011, annual report with strategic plan Maryland office of the public defender. http://www.opd.state.md.us/Index%20Assets/Annual%20Report%20FY2011.pdf

- Douglas v. California (1963) 372 US 353

- Gideon v. Wainwright (1963) 372 US 335

- Halbert v. Michigan (2005) 545 US 605

- Hansen RA, Hewitt WE, Ostrom BJ, Lomvardias C (1992) Indigent defenders get the job done and done well. National Center for State Courts, Williamsburg

- In re Gault (1967) 387 US 1

- Johnson v. Zerbst (1938) 304 US 458

- Justice Policy Institute (2011) System overload: the costs of under-resourcing public defense July 2011

- Kleiman M, Lee CG (2010) Virginia indigent defense commission: attorney and support staff workload assessment. National Center for State Courts, Williamsburg

- Langton L, Farole D Jr (2010) State public defender programs, 2007. Bureau of Justice Statistics September, NJC 228229

- Lefstein N (2011) Excessive public defense workloads: are ABA standards for criminal justice adequate? Hast Const Law Q 38(4):949–982

- Lefstein N, Spangenberg RL (2009) Justice denied: America’s continuing neglect of our constitutional right to counsel: Rep of the National Right to Couns Comm

- McIntyre L (1987) The Chicago public defender. University of Chicago: University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- National Legal Aid and Defender Association (2004) In defense of public access to justice: an assessment of trial-level indigent defense services in Louisiana 40 years after Gideon. Washington, DC

- National Legal Aid and Defender Association (2008) Evaluation of trial-level indigent defense systems in Michigan. National Legal Aid and Defender Association, Washington, DC

- Ostrom BJ, Kleiman M, Ryan C (2005) Maryland attorney and staff workload assessment, 2005. National Center for State Courts, Williamsburg

- Platt A, Pollock R (1974) Channeling lawyers: the careers of public defenders. Issues Criminol 9(1):1–31

- Powell v. Alabama (1932) 287 US 45

- Rothgery v. Gillespie County (2008) 554 US 191

- Standing Committee on Legal Aid and Indigent Defendants, American Bar Association (2002) ABA ten principles of a public defense delivery system

- Steelman DC, Tallarico SK, Kleiman M, Fanflik PL (2007) A workload assessment study for the New Mexico trial court judiciary, New Mexico district attorneys’ offices, and the New Mexico public defender department. National Center for State Courts, Williamsburg

- Strickland v. Washington (1984) 466 US 668

- Vagenas GN, Bethke JD, Dattel M, Desilets R, Newhouse DJ, Spangenberg R (2009) Indigent defense chapter 11 in the state of criminal justice. American Bar Association Criminal Justice Section

- Washington Defender Association WDA standards for public defense services standard three: caseload limits and types of cases. http://dev21.npowerseattle.org/wda/resources/standards/wda-standards-for-public-defense-services/standard-three-caseload-limits-andtypes-of-cases/

- Wice PB (2005) Public defenders and the American justice system. Praeger, Westport

- Williams PH, Bost WM Jr (1971) The assigned counsel system: an exercise of servitude? Miss Law J 42:32–59

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.