This sample Risk Assessment, Classification, And Prediction Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Over the years, the assessment of offenders has evolved from using one’s “gut feeling” to decide who is likely to reoffend, to instruments that have focused on past behavior (static indicators), and to what are now called fourth generation assessments. These instruments combine static and dynamic (changeable) factors to more accurately predict risk of recidivism. They identify the crime-producing needs that should be targeted for change, and produce results that can be fully integrated into case plans used to manage what programs and services offenders receive as well as gauge progress (Andrews Bonta and Wormith 2006).

One of the foundations of developing effective correctional practices and programs is adoption of a validated risk assessment. Once focused primarily on the seriousness of the offense, the criminal justice system is now speaking in terms of risk and need factors. Hence, the risk level of the offender becomes the primary consideration for treatment and supervision over the offender’s felony level. As departments adopt a risk, need, and responsivity (RNR) framework, the importance of assessing for risk has been elevated. In fact, many of the leading professional correctional organizations fully endorse the use of risk assessment in assisting in classification decisions and delivery of evidence-based practices (American Association of Community Justice Professionals, American Probation and Parole Association, and the International Community Corrections Association). To understand the impact risk assessment has had on corrections, this research paper reviews the history of risk assessment, provides a framework for understanding the context in which assessment should be adopted, and discusses the current controversies surrounding the development of 3rd and 4th generation risk assessments. Finally, this research paper provides recommendations for the field in regard to adopting risk assessment and using the results to best inform correctional practices.

What Do Risk Assessments Measure?

This seems to be a straightforward question. However, people have different concepts of “risk” and different instruments measure “risk” for different types of behavior. For some, “risk” is a concept associated with the seriousness of the crime. For example, a felon must be higher risk than a misdemeanant. Even though a felon has been convicted of a more serious offense than a misdemeanant, his or her relative risk of reoffending may have nothing to do with the seriousness of the crime. For most, “risk” refers to the probability of reoffending. A low-risk offender is one with a relatively low probability of committing a new offense (i.e., relatively prosocial people with few risk factors), while a high-risk offender has a much greater probability of future engagement in crime (i.e., more antisocial with several risk factors). While many in the criminal justice system are interested in the likelihood of reoffending, there are also assessments used in corrections that assist in determining if an offender is suicidal or likely to commit a violent act, be a victim of violence, engage in future sex offenses, engage in misconducts while incarcerated, etc. The purpose of the assessment dictates the outcome it measures. For example, a pretrial tool is likely to predict failure to appear in court and short-term behavior, while an institutional classification system will provide staff with a prediction of institutional misconducts. The focus in this research paper is on the use of risk assessments to predict future criminality among offenders.

History Of Risk Assessment

From the early beginning of community corrections, there has been an attempt to predict who will reoffend. Even prior to the use of actuarial tools, corrections professionals have tried to determine the likelihood that offenders would engage in future criminal behavior (Monahan 1977). Without the assistance of empirically based assessments, correctional workers have been forced to use a wide array of clinical assessments to draw on their professional experiences to make prognoses regarding offenders’ likelihood of reoffending. The problem is that professional judgment alone is not very accurate. Dawes et al. (1989) found that clinical judgment was not accurate compared to statistical prediction for a range of outcomes. Ultimately, they concluded that humans take into account factors that are not predictive, weigh characteristics that are less predictive, and even when given additional training, do not outperform statistical models. Without a structured assessment process using validated and objective measures, corrections will be limited in what it can do to reduce recidivism (Latessa 2004). Adopting a risk assessment can help the criminal justice system identify the offenders who are at highest risk for recidivating, assist in enhancing public safety by ensuring that those higher-risk offenders receive appropriate supervision and interventions, help reduce bias in making decisions, and improve placement and utilization or resources.

Clinical Judgment, Structured Professional Judgment, And Actuarial Assessments

Three primary ways to assess offenders are clinical judgment, structured professional judgment, and actuarial (also called statistical) methods. As discussed in the previous section, clinical judgment is the process in which a staff person collects information and makes a decision about risk based on “gut feelings” or intuition. Clinical judgment relies on the skills, knowledge, and ability of individual staff to gather appropriate information and then to make a decision based on the totality of the information. In contrast, structured professional judgment combines clinical judgment and theoretically relevant measures into a single assessment – putting limits on the evaluators’ biases while still tapping into their professional knowledge (Borum and Douglas 2003). Tools based on structured professional judgment are designed to help staff determine what they can do to disrupt future recidivism, not necessarily predict who will reoffend. The tools based on structured professional judgment are not scored per se; there are no cutoffs produced or a final composite risk score; instead specific areas in which the evaluator will rate the offender based on low-, moderate-, and high-risk levels are provided. These tools consider static and dynamic factors, protective factors, and contextual factors to assist correctional professionals to guide decisions regarding risk management (Vincent et al. 2009). One example is the Structured Assessment of Violence Risk in Youth (SAVRY), which is based on structured professional judgment along with standardized risk factors. With this tool an evaluator assesses a youth on 24 items and determines if the youth presents as low, moderate, or high risk for each indicator. Upon identifying the level of risk for each item, the assessor will make a final determination of the youth’s overall level of risk. The SAVRY has demonstrated intraclass correlation coefficients of 0.81 and produced correlations with recidivism that range from 0.25 to 0.70.

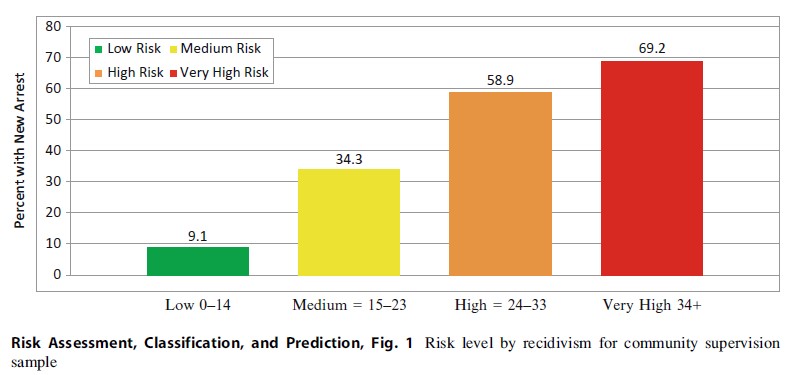

A third method in conducting risk assessment is the actuarial method. Actuarial risk assessment is similar to what insurance companies use to calculate insurance rates. Actuarial instruments are based on statistical analysis of records and other information that result in the development of probability tables: if you score X you have an X chance of reoffending. The foundation of statistical risk assessments in corrections is similar to that in most actuarial sciences. For example, life insurance is cheaper for a nonsmoker in his 40s than a smoker of the same age. The reason insurance costs more for the smoker is that smokers have a risk factor that is significantly correlated with health problems – which runs a greater risk that the insurance company will have to pay out a claim before they recoup their money. Similarly, an offender who uses drugs and is unemployed has a higher chance of reoffending than someone who does not use drugs and has steady employment. Figure 1 shows how a distribution of offenders might be classified according to risk. Note that the probability of someone in the low-risk category reoffending is less than 10 %, moderate risk is 34 %, high risk is nearly 60 %, and very high risk is about 70 %.

Types Of Assessment Tools

In addition to the methods by which assessments are designed, there are three unique types of risk assessments. Screening instruments are designed to assess a large population (usually at intake) to predict a specific outcome by sorting offenders into risk categories quickly. Screening tools are usually comprised of static items (e.g., criminal history) and can be completed by either a file review or a brief interview. They are typically used to separate low-risk from moderate=and high-risk offenders but have little utility beyond identifying levels of risk due to a limited number of dynamic items.

Beyond screening tools, comprehensive risk/ need assessments are designed to gather more complete data to assist in determining levels of risk. They typically are longer to administer, require training, and can be used to identify targets for treatment. These instruments include a range of dynamic factors that can be used to reassess the offender. Furthermore, composite risk assessments can be used to develop case plans to ensure that programming targets criminogenic needs of the offender (Latessa and Lowenkamp 2005a).

Once a comprehensive risk assessment is completed, specialized assessments can be used to assess specific domains (like substance abuse) or special populations (i.e., sex offenders, mentally ill offenders, psychopaths). Specialized assessments can be completed on offenders who are flagged as risky on composite risk/needs tools. These instruments usually require additional training, while some tools require special licensures to conduct.

In many instances jurisdictions adopt all three types of assessments. A screening instrument might be used at pretrial or to assess offenders at intake to determine who needs further assessment. For those offenders who continue deeper into the system, a more comprehensive assessment tool would be used. Once assessed on a composite risk tool, specialized assessment should be prescribed on an as-needed basis. Following this approach can increase efficiency, since not all offenders will be thoroughly assessed, but those offenders who appear to pose the greatest risk to reoffend will be examined much more closely (Flores Russell Latessa and Travis 2005).

Risk, Need, And Responsivity

As agencies become more familiar with risk assessments and incorporate risk assessments across multiple decision points, it is important to understand how the results can be used to guide decisions in the field of corrections. The risk, need, and responsivity principles provide the context in which the results can be used to best serve the corrections population.

Risk Principle

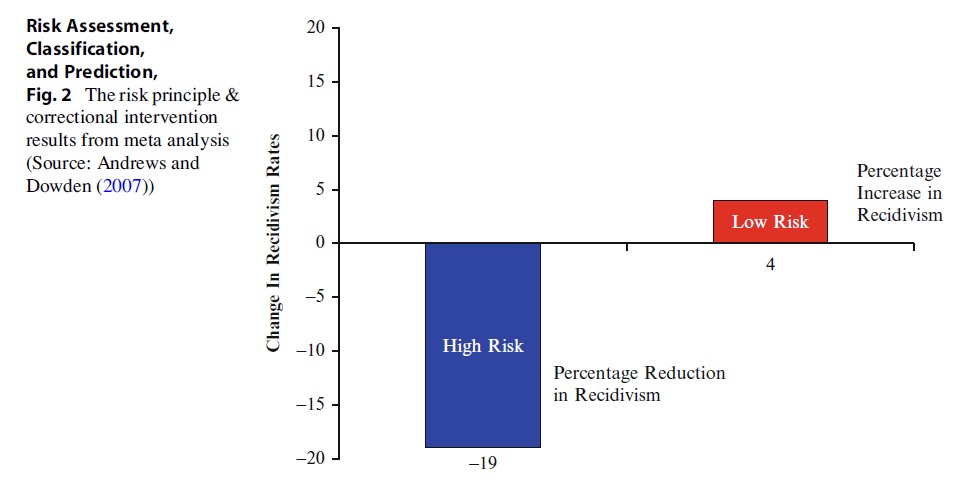

The risk principle offers guidelines to correctional workers on which offenders are best served and under what conditions. Andrews Bonta and Hoge (1990) suggest that corrections should target those offenders with a higher probability of recidivism, provide the most intensive treatment to higher-risk offenders, and refrain from disrupting the lives of low-risk offenders. Although often ignored, correctional interventions that adhere to the risk principle demonstrate significantly greater reductions in recidivism (Latessa Brusman and Smith 2010). Consider a program that serves 100 low-risk offenders. Without intervention, approximately ten of the 100 offenders will reoffend. For the program to be effective, it would have to reduce recidivism for a portion of the ten offenders while not increasing recidivism for the other 90. In contrast, a program that serves 100 high-risk offenders would expect a recidivism rate of 60 %. For the program to be effective, it would have to reduce recidivism for a portion of the 60 offenders – resulting in a greater chance of reducing recidivism while reducing the chance of disrupting those that would not reoffend. The more troubling aspect to the risk principle is the fact that providing intensive interventions for low-risk offenders can actually increase failure rates (Lowenkamp and Latessa 2004). This effect is illustrated in Fig. 2, which shows the average changes in recidivism rates when we target highand low-risk offenders.

While it makes sense that programs can have an impact on higher-risk offenders, it is not as evident why programs would increase recidivism for low-risk offenders. First, when low-risk offenders are placed in more intensive settings, they are more likely to be exposed to higher-risk offenders – increasing the likelihood of an iatrogenic effect. Considering the number of settings where lower-risk offenders are potentially mixed with higher risk – community service, treatment programs, jail, and prison – it is not surprising that lower-risk offenders are often more risky upon completion. Second, for low-risk offenders, residential programs, jails, and prisons actually disrupt what makes them low risk, causing the likelihood of recidivism to increase. For example, if you placed your low-risk child in a residential program for six months due to a substance abuse problem that child would miss out on education programming, he or she would experience family disruption, the youth’s prosocial attitudes and friends would be replaced with antisocial thoughts and antisocial peers, and his or her friends’ parents would likely not be interested in exposing their child to yours once released. In other words, risk would be increased, not reduced due to placement of the youth. Third, low-risk offenders are often victimized, taken advantage of, and pressured into engaging in antisocial behavior by more sophisticated offenders (Lowenkamp Latessa and Holsinger, 2006).

Grounded in the risk principle, the system should identify lower-risk offenders and provide alternative services to them without disrupting what makes them low risk. As a general rule, low-risk offenders should be excluded from intensive correctional programs. In order for the criminal justice system to adhere to the risk principle, offenders must be assessed and decisions must be made regarding the appropriate placement of lower risk offenders. If ignored, the results can be alarming. This was seen in a 2010 study conducted in Ohio that examined the effect of placing offenders in a halfway house versus regular supervision (Latessa Brusman and Smith 2010). Placing a low-risk offender in a halfway house led to an average 3 % increase in failure rates, while placing a high-risk offender in the same program resulted in an average 14 % reduction in recidivism.

Need Principle

The need principle suggests that there are specific targets that should be addressed if the system is expecting to reduce recidivism. Research by Andrews, Bonta, Gendreau and others have identified seven dynamic areas associated with criminal conduct:

- Antisocial/procriminal attitudes, values, and beliefs

- Criminal peers and the lack of prosocial others

- Antisocial temperament

- Family

- Education, employment, and finances

- Limited prosocial leisure activities

- Substance abuse

While the risk principle suggests that higher-risk offenders should be targeted for more intensive services, the need principle points to which needs should be addressed. Although most third and fourth generation risk assessments include both static and dynamic factors, the need principle is more concerned with those that can change (dynamic). Dynamic items include factors like who an offender chooses to hang around with, his or her attitudes and values towards crime, a lack of problem solving skills, substance use, and employment status. All these factors are derived from several decades of research and are correlated with recidivism. These dynamic factors are also called criminogenic needs: crime-producing factors that are strongly correlated with the risk of reoffending. Combining static and dynamic factors together gives the best picture of overall risk of recidivism and the most effective way to target criminogenic needs (Latessa and Lowenkamp 2005b). For example, people who are at risk for a heart attack usually have some common characteristics: over 50 years old, male, a family history of heart problems, high blood pressure, excessive weight, smoking, stress, and high cholesterol. While some of these are historical or static factors, others are dynamic. The benefit of assessing the dynamic factors is that if addressed, the high-risk patient can actually decrease his or her risk of having a heart attack. Similarly, dynamic items on a criminogenic risk assessment can provide malleable targets for risk to reoffend.

The need principle provides a roadmap to programs to ensure that appropriate criminogenic needs are targeted. Programs would benefit from targeting crime-producing needs, such as antisocial attitudes, antisocial peer associations, substance abuse, lack of problem solving and self-control skills, and other factors that are highly correlated with criminal conduct (Dowden and Andrews 1999). Identifying criminogenic needs is an important part of offender risk assessment; since it tells us “what” to focus on to reduce risk.

Responsivity Principle

The responsivity principle suggests that we should match the style and mode of service delivery based on key offender characteristics, such as culture, gender, mental health, or learning ability. This may not decrease risk, but will increase the likelihood of success in correctional interventions. One of the limitations of corrections is its ability to deliver services based on individual needs of the offender. The criminal justice system’s reliance on group interventions has made it very difficult to ensure that interventions are individualized. For example, offenders who have cognitive delays may not respond well to group treatment focused on insight-oriented processes. There are often personal characteristics of an individual that should be assessed, since these factors can effect their engagement in treatment. These would include areas like mental and emotional problems, cognitive functioning, and level of motivation or readiness to change. Assessment of these areas can often improve the placement of offenders, assist with case planning, and impact the overall effectiveness of correctional treatment.

Controversies In Risk Assessment

Although the criminal justice field has moved beyond “gut feelings” as its primary form of assessment, there still remain several questions regarding the implementation of risk assessments. The first question relates to the applicability of risk assessments at the time of sentencing. From 1975 to 2002 incarceration rates increased by more than 300 % (Stemen et al. 2005). As the “get tough” movement took hold, many jurisdictions moved to determinate sentencing, stricter sentencing guidelines, and abolition of post-release supervision – resulting in massive numbers of offenders committed to state institutions. As a result, many have been calling for the implementation of risk reduction efforts at sentencing (Pew Center 2009). In fact, the Pew Center has identified the adoption of a risk assessment at sentencing as one of their top ten recommendations to control escalating prison populations.

Of course, adopting a risk assessment at sentencing is not supported by all. Singer (1979) suggests that prison is not intended to address recidivism; the point of prison is to mete out a punishment commensurate with the harm to the victim. Others suggest that risk assessment should be used to develop appropriate targets for change post-sentence. In 2010, the Indiana Supreme Court upheld a decision by a trial judge to use the results of a risk assessment to inform the overall manner in which a sentence was to be served (Malenchik v State 2010).

A second question that has been raised regarding risk assessment is whether a single composite score comprised of risk and need factors should be used or should risk and needs be separated into two unique tools. Baird (2009) argues that risk assessment should be split into separate risk and needs assessments, suggesting that the risk index should be reserved for a fewer set of items that have moderate to high correlation. Limiting risk assessments to fewer, more highly correlated items will allow for greater parsimony, increase prediction, and ensure that staff can score the items accurately. The need assessment should be separately scored and based more on clinical judgment or instruments designed to determine why people commit crime – suggesting that composite risk tools cannot accurately measure individual level needs. In contrast, Bonta (2002) recommends that risk assessment should include items that are theoretically relevant, have multiple measures or items per domain, incorporate a combination of static and dynamic factors, and employ a multi-method approach to understanding risk. Risk assessments designed using Bonta’s approach will typically hold more items, will measure risk using theoretically derived measures, and will focus more on the utility of the tool than parsimony.

The third question is whether third and fourth generation tools can meet acceptable levels of inter-rater reliability – that is, can different assessors come to the same decision based on the same information. Austin et al. (2003) suggests that measures of inter-rater reliability should reach a minimum of 0.70 for a risk assessment to be deemed reliable. The argument regarding third and fourth generation tools is that they typically include a significant number of dynamic items – which, in turn, are difficult to accurately rate. While Austin et al. (2003) and Baird (2009) point to third and fourth generation tools lacking reliability, there are many studies that have demonstrated that these tools can achieve acceptable levels of reliability with training. In fact, Austin found significant increases in reliability for the LSI-R when staff was provided with training on the instrument.

The fourth area in which there are questions regarding the use of fourth generation tools is in regard to using the results to develop individualized case plans. Can fourth generation risk assessments be used to identify treatment targets for individual offenders? The answer is mixed. Fourth generation tools typically identify levels of need by domain. For example, the Ohio Risk Assessment System-Community Supervision Tool (ORAS-CST) provides low, moderate, and high levels of need by each of the seven domains. These cutoffs assist staff in readily identifying areas that are riskier for offenders and help to form appropriate treatment targets. These domains are used to “flag” areas of need. Once an offender is identified as having moderate to high need in an area, the worker will want to explore each domain in greater detail to determine the individualized needs of the offender. For example, offenders that present a high risk of substance abuse may have different reasons for being high-risk substance abusers. For example, one offender may be physiologically or psychologically addicted to drugs. A second person may use drugs not because she or he is addicted, but because the offender spends significant amounts of time with peers that use drugs. A third person might use drugs to mask an underlying mental illness. All three offenders are high risk in regard to substance use, but present with uniquely different targets for treatment. Traditional drug treatment may work for the offender who is addicted, but that type of intervention may not be very effective for an offender who uses due to peer networks. In fact, sending an offender to a substance abuse group or AA/NA may not be appropriate given the treatment target is really antisocial peers. For the third group, if the underlying issue is mental health, helping an offender reduce substance use will have no impact on the symptoms of mental illness – again resulting in an intervention that has little impact on the presenting problem. To address the fact that any one need domain has a number of potential treatment targets, an offender who has a moderate to high level of need in a domain-specific area should receive additional need specific assessments to determine the individual level treatment targets.

The fifth question is in regard to the ability of risk assessments to measure change over time. Several studies have been conducted to examine the impact of a change in composite risk score on the LSI-R. Andrews et al. (2006) argues that offenders can change and that risk assessments should reflect the ability to measure these changes. Andrews and Robinson (1984) have found support for the ability of the LSI-R to predict change over time. In contrast, Baird argues that the use of third and fourth generation tools have significant limitations in measuring change over time. Moreover, he suggests that risk tools should be modified between intake and reassessment – shifting emphasis from prior history items to current behaviors.

These instruments use dynamic risk factors to measure initial risk and then reassess on these items to determine if the offender has made any significant changes in the risk he/she poses to society. In addition to targets of change, the fourth generation tools allow departments to focus their resources on those domains (broad area of need) that are moderate to high risk. Ultimately, if the criminal justice system can significantly reduce the recidivism rates for offenders, this will result in increased public safety. The fourth generation tools provide agents of change with a specific “road map” to address the needs of the offenders, manage limited resources, and protect public safety.

Obstacles To Good Practice

Here are some of the more common obstacles that exist with regard to offender assessment:

- Offenders are assessed, but the process ignores important factors. Sometimes this is because the tool selected is comprised mainly of static predictors, or the assessment process focuses on one or two domains (like substance abuse) to the exclusion of other important risk factors.

- Offenders are assessed, but the process does not distinguish quantifiably determined levels (i.e., high, moderate, low). This is common with narrative assessments, and the result is often that the summaries all read the same: “offender is at risk to reoffend unless they get substance abuse treatment.” This type of information tell us little about the actual risk the offender poses to reoffend or the level of need in specific areas. This is common with clinical assessment processes.

- Even when offenders are comprehensively assessed, the results are not used – everyone gets the same treatment. As we will discuss below, adopting a risk assessment tool is only one step in the process. If the information is not going to be used then why assess?

- Staff members often are not adequately trained in the use of the instruments, or they are only trained when the new instrument is selected. Usually, when a decision to use a new instrument is made, everyone is trained, but as time goes on and new employees are hired, little refresher training may be done, and the new staff simply learn how to use the tools by watching the older staff. The result is that reliability and validity suffer, and stakeholders lose confidence in the results of the assessment.

- Staff resistance is one of the most persistent obstacles to overcome. Some of the common refrains that are heard by a staff include “I just need to talk to them for 5 minutes to determine their level of risk,” “we don’t have time to conduct an assessment,” “they are all high risk,” and “they all get the same treatment anyway so why assess them?” While staff resistance can be a challenge, it is not insurmountable, and as Jones Johnson Latessa and Travis (1999) found, most community correctional agencies understand the importance and value of using a valid and reliable risk assessment tool.

To avoid these and other mistakes and to derive the full value from assessments, there are some points to consider (Latessa and Lowenkamp 2005b; Latessa (2004)):

- There is no “one size fits all” assessment tool. Some domains or types of offenders will require specialized assessments, such as sex offenders or mentally disturbed individuals. In addition, the use or purpose will vary. For example, the assessment tool for making a decision about whether to grant pretrial release may be different from one for making a decision about whether to grant probation.

- Actuarial assessment is more accurate than clinical assessment, but remember, no process is perfect and there will always be false positives and false negatives – sometimes low-risk offenders reoffend, and sometimes high-risk offenders are successful.

- Assessment is usually not a “one-time” event, especially if the offender is under some form of community control. Offender risk and need factors change, so it is important to consider assessment as an ongoing process.

- Assessments help guide decisions, but they do not make them – professional discretion is part of good assessment-aided decision-making.

- While the new dynamic assessment tools can produce more useful information, they require more effort to insure reliability – they require staff training and continual monitoring of the assessment process. Fidelity and quality assurance make a difference.

- Good risk assessment serves a number of functions and helps guide decisions by providing reliable information in a systematic and objective manner. It can be the cornerstone of a more effective, efficient, and just system.

- A flexible process should be developed that expands as needed – higher-risk offenders need more assessment.

- Processes and instruments should be standardized so that everyone is speaking the same language with regard to risk assessment.

- Regardless of the assessment tool used, staff should be thoroughly trained on the rationale and use of a risk assessment tool. Proper training will ensure that the staff understand the advantages of risk assessment and that they use the tool in an appropriate and consistent manner. The level and amount of staff “buy in” can drastically affect the level of success in implementing a risk assessment process or tool (Lowenkamp Holsinger Latessa 2004).

- Following training, agency administrators should establish quality assurance processes such as periodic audits of assessments, refresher training, or even certification of assessors.

- Assessment results should be used to develop case supervision and treatment plans and to assign offenders to programs.

- Information should be shared with service providers so that they understand the risk of the offender they are involved with as well as the criminogenic factors that need to be targeted.

- An assessment tool should be validated on the population for which it is being used. There are several widely used actuarial instruments that have been validated in numerous settings and across several subgroups (i.e., males, females, different racial, and ethnic groups). Nonetheless, agencies should still analyze assessment results based on the population for which the tool is being used.

Bibliography:

- Andrews DA, Bonta J (1998) The psychology of criminal conduct. Anderson, Cincinnati

- Andrews DA, Dowden C (2007) The risk-need-responsivity model of assessment and human service in prevention and corrections: crime-prevention jurisprudence. Can J Criminol Crim Justice 49:439–464

- Andrews DA, Robinson D (1984) The level of supervision inventory: second report. Report to Research Services. Ontario Ministry of Correctional Services, Toronto

- Andrews DA, Bonta J, Hoge R (1990) Classification for effective rehabilitation: rediscovering psychology. Crim Justice Behav 17:19–52

- Andrews DA, Bonta J, Wormith SJ (2006) The recent past and near future of risk and/or need assessment. Crime Delinq 52:7–27

- Austin J, Coleman D, Peyton J, Johnson KD (2003) Reliability and validity study of the LSI-R risk assessment instrument. Institute on Crime, Justice, and Corrections at the George Washington University, Washington, DC

- Baird C (2009) A question of evidence: a critique of risk assessment models used in the justice system. National Council on Crime and Delinquency, Madison

- Bloom HS, Singer NM (1979) Determining the cost-effectiveness of correctional programs: the case of patuxent institution. Eval Rev 3:609–628

- Bonta J (2002) Offender risk assessment: guidelines for selection and use. Crim Justice Behav 29:355–379

- Bonta J, Wormith SJ (2008) Risk and need assessment. In: McIvor G, Raynor P (eds) Developments in social work with offenders. Jessica Kingsley, London, pp 131–152

- Borum R, Douglas K (2003) New directions in violence risk assessment. Pyschiatr Times 20(3):102–103

- Dawes R, Faust D, Meehl P (1989) Clinical versus actuarial judgment. Science 31:1668–1674

- Dowden C, Andrews DA (1999) What works in young offender treatment: a meta-analysis. Forum Correct Res 11:21–24

- Flores AW, Russell AJ, Latessa EJ, Travis LF (2005) Evidence of professionalism or quackery: measuring practitioner awareness of risk/need factors and effective treatment strategies. Fed Probat 69(2):9–14

- Jones DA, Johnson S, Latessa EJ, Travis LF (1999) Case classification in community corrections: preliminary findings from a National Survey, Topics in community corrections. National Institute of Corrections, U.S. Department of Justice, Washington, DC

- Latessa EJ (2004) Best practices of classification and assessment. J Commun Correct X11(2; Winter 2003–2004):27–30

- Latessa EJ, Lowenkamp CT (2005a) What are criminogenic needs and why are they important. For the record (fourth quarter): 15–16

- Latessa EJ, Lowenkamp CT (2005b) The role of offender risk assessment tools and how to select them. For the record (fourth quarter): 18–20

- Latessa E, Brusman L, Smith P (2010) Follow-up evaluation of Ohio’s community based correctional facility and halfway house programs. Center for Criminal Justice Research, Cincinnati

- Lowenkamp CT, Latessa EJ (2004) Understanding the risk principle: how and why correctional interventions can harm low-risk offenders, Topics in community corrections. National Institute of Corrections, U.S. Department of Justice, Washington, DC, pp 3–8

- Lowenkamp CT, Latessa EJ (2005) Increasing the effectiveness of correctional programming through the risk principle: identifying offenders for residential placement. Criminol Public Policy 2(4):15–24

- Lowenkamp CT, Holsinger A, Latessa EJ (2004) Assessing the inter-rater agreement of the level of service inventory revised. Fed Probat 68(3):34–38

- Lowenkamp CT, Latessa EJ, Holsinger A (2006) The risk principle in action: what we have learned from 13,676 offenders and 97 correctional programs. Crime Delinq 52(1):1–17

- Malenchik v. State of Indiana, No. 79S02–0908–CR–365 (Ind., 2010)

- Monahan J (1977) Strategies for an empirical analysis of the prediction of violence in emergency civil commitment. Law Hum Behav 1:363–371

- Pew Center on the States (2009) One in 31: the long reach of American corrections. The Pew Charitable Trusts, Washington, DC

- Singer R (1979) Just deserts sentencing based on equity and desert. Ballinger, Cambridge, MA

- Stemen D, Rengifo A, Wilson J (2005) Of fragmentation and ferment: the impact of state sentencing policies on incarceration rates, 1975–2002. Vera Institute of Justice, New York

- Vincent G, Terry A, Maney S (2009) Risk/needs tools for antisocial behavior and violence among youthful populations. In: Andrade J (ed) Handbook of violence risk assessment and treatment: new approaches for forensic mental health practitioners. Springer, New York, pp 377–423

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.