This sample Role And Function Of The Police Manager Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

If, as Shakespeare (1597) wrote in “Henry IV,” it is true that “Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown,” then certainly the nature of policing in general has never allowed police leaders the luxury of being able to “lie easy.” The police profession, like the rest of the nation, is undergoing radical changes in leadership and supervision.

Furthermore, practices that worked for police managers of the past will no longer suffice today. The autocratic, control oriented police leadership methods of the past are changing to the empowerment and participative management styles; the paramilitary command and control operations used even a few years ago do not work well with today’s officers, who respond instead to intellectual challenges, stimulation, and motivation. More specifically, past expectations and measures of the police function were quite different, often requiring that officers essentially perform like human pinballs – reactively hurrying from call to call, exiting the patrol vehicle at the scene and taking the report, and then returning to the patrol car to resume patrol (seldom if ever accomplishing anything long-term regarding crime control); furthermore, officers were typically evaluated by their police leaders in terms of numbers: arrests, traffic citations, response times, and even the numbers of miles driven during the duty shift, all of which were indicators of productivity. Officers were not encouraged to visit with citizens to obtain feedback about neighborhood crime and disorder; in fact, they were expected by their leadership, as stated by police expert Chris Braiden (1993), to “park their brains at the door of the stationhouse, and follow orders like a robot.” Many of today’s police executives can well remember these facets of policing that prevailed during that era, when they were young officers.

Adding to the historical challenges of police leaders are the contemporary economic woes across the USA – perhaps affected more than ever before by the financial contractions and upheavals in foreign venues – which have led to unprecedented municipal bankruptcies, police layoffs, and even a lack of job security for police personnel. Therefore, undoubtedly some of the most important and challenging positions in our society and times involve police leadership.

This essay examines the roles and functions of those leaders, including administrators, middle managers, and supervisors. Leadership is the heart and soul of any organization, and the idea of leadership has been with us for a long time. Yet leadership is still, and will always be something of an amorphous concept, dependent on the situation and the motivations and abilities of the people involved. There are theories that can guide leaders, but for some, good leadership may be a bit like the US Supreme Court’s attempts at defining obscenity – summarized by Justice Stewart when he said: “I know it when I see it.” This essay will thus serve to bring this concept into clearer relief.

Definitions Of Key Terms

Although the terms administration, manager/ middle management, and supervisor are often used synonymously, each is a unique concept that occasionally overlaps with the others. Administration encompasses both management and supervision. Administration is a process whereby a group of people are organized and directed toward achievement of the group’s objective. Administration focuses on the overall organization and its mission and its relationship with other organizations and groups external to it. Administrators are often concerned with the department’s direction and its policies and with ensuring that the department has the resources to fulfill its community’s expectations. Police administrators generally include the chief, assistant chiefs, and high-ranking staff who support the chief in administering the department.

Middle management, which is also a part of administration, is most closely associated with the day-to-day operations of the various elements within the organization. For example, most police departments have a variety of operational units such as patrol, criminal investigation, traffic, gang enforcement, domestic violence, or community relations. Each of these units is run by someone who is most aptly described as a manager. In most cases, these managers are captains or lieutenants. These managers ensure that their units fulfill their departmental mission and work closely with other units to ensure that conflict or problems do not develop. They also attend to planning, budgeting, and human resource or personnel needs to ensure that the unit is adequately prepared to carry out its responsibilities.

Supervision involves the direction of officers and civilians in their day-to-day activities, often on a one-to-one basis. Often termed “first-line supervisors” (and typically being sergeants in a police or prison organization), these individuals ensure that subordinate officers adhere to departmental policies, complete tasks correctly and on a timely basis, and interact with the public in a professional manner. Supervisors often observe their subordinates completing assignments and sometimes take charge of situations, especially when a deployment of a large number of officers is needed. They also work closely with managers to ensure that officers’ activities are consistent with the unit’s mission and objectives.

This essay focuses more on the administrative level, but will briefly discuss the roles of middle managers and supervisors as well.

Applicable Theories

It has been said that behind every good practice is a good theory. Certainly any number of theories could be offered to inform and guide the actions of police leaders, explain how they should manage and motivate their personnel, and so on. This section discusses three applicable theories underlying police leadership: Katz’s three skills of chief executive officers, the managerial grid, and situational leadership.

Early ideas about leadership tended to take a simplistic view, assuming that leadership was simply a matter of birth: the so-called “Great Man” theory of leadership, where leaders were born into leadership positions (e.g., monarchs). This definition is inadequate, however, because leadership today involves much more than one’s birthright, and is a complex undertaking as well.

There is also a long-standing debate concerning whether one’s ability to manage is an art or a science – that is, whether certain people are “born with” or predisposed to having the qualities necessary for being effective managers; or, conversely, whether management is an “acquired” ability or science because people can be taught to be effective managers. Many people believe management contains the elements of both, as it requires both managerial skill that is personal (art), as well as a systematized body of knowledge (science) for preparing, organizing, and directing subordinates to accomplish the goals of the organization.

Katz’s Three Essential Skills

Robert Katz (1974) identified three essential skills that leaders should possess: technical, human, and conceptual. Each of these skills, when performed effectively, results in the achievement of objectives and goals, which is the primary thrust of organization and management. Technical skills are those a leader needs to ensure that specific tasks are performed correctly. They are based on proven knowledge, procedures, or techniques. Technical skills may involve knowledge in areas such as high-risk tactics, law, and criminal procedures. The police sergeant usually depends on training and departmental policies for technical knowledge. The areas in which leaders need technical skills include computer applications, budgeting, strategic planning, labor relations, public relations, and human resources management. They must also have knowledge of the technical skills required for the successful completion of tasks that are within his or her command. Human skills involve working with people and include being thoroughly familiar with what motivates employees and how to utilize group processes. Katz visualized human skills as including “the executive’s ability to work effectively as a group member and to build cooperative effort within the team he leads. Katz added that the human relations skill involves tolerance of ambiguity and empathy. Tolerance of ambiguity means that the manager is able to handle problems when insufficient information precludes making a totally informed decision. Empathy is the ability to put oneself in another’s place or to understand another’s plight. Conceptual skills involve coordinating and integrating all the activities and interests of the organization toward a common objective. Katz considered such skills to include “an ability to translate knowledge into action” and emphasized that these skills can be taught to actual and prospective leaders. Thus, good leaders are not simply born but can be trained to assume their responsibilities.

All three of these skills are present in varying degrees for each level of leadership. As one moves up the hierarchy, conceptual skills become more important and technical skills less important. The common denominator for all levels of leadership, however, is human skills. In today’s unionized and litigious environment, it is inconceivable that an administrator could neglect the human skills.

The Managerial Grid

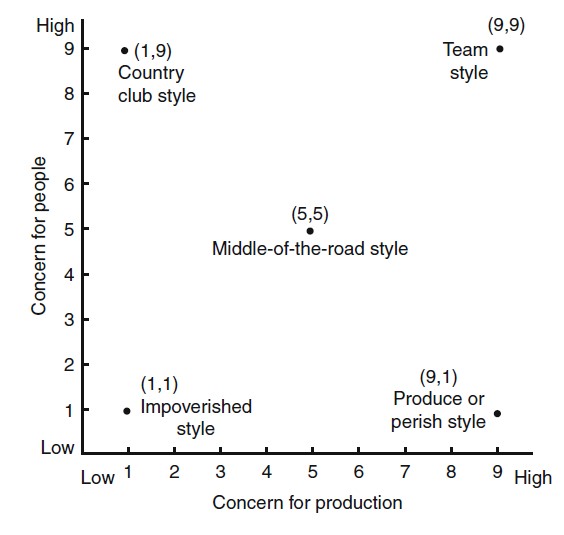

The managerial grid, developed by Robert R. Blake and Jane S. Mouton (1962), has two dimensions: (1) concern for production and performance, and (2) concern for people (e.g., human relations, empathy). View the former, production, as being placed on a horizontal axis and the latter, concern for people, as being placed on a vertical axis, with both numbered from 1 to 9 (1 meaning low concern, to 9, indicating a high concern). The way in which a person combines these two dimensions will determine one’s leadership style in terms of one of the five principal styles identified on the grid.

For example, one’s management style that is located in the lower-left-hand corner of the grid would represent a minimal concern for task or service and a minimal concern for people. Conversely, one whose style is located at the lower-right-hand corner of the grid identifies a style having a primary concern for the task or output and a minimal concern for people. The upper-left-hand corner is often referred to as “country club management,” with minimum effort given to output or task. The upper-right would indicate high concern for both people and production – and thus a team management approach of mutual respect and trust. In the center – a “middle-of-the-road” style – the leader has a more compromising, “be fair but firm” philosophy, providing a balance between output and people concerns.

Situational Leadership

Not too different from the managerial grid is situational leadership theory, which recognizes that the workplace is a complex setting and subject to rapid changes; therefore, it is unlikely that a single leadership style would be adequate. Simply put, this theory argues that the leadership style to be used in an organization will depend on the situation – the subordinates’ readiness, motivation to do their job, as well as their ability or competence to accomplish it. Therefore, as Hersey and Blanchard (1977) asserted, the leader’s behavior is in relationship to followers’ behavior, and the leader must evaluate subordinates’ status in terms of their willingness or motivation, and ability or competence. To be effective, subordinates must be mature in their view of and approach to their job; maturity is defined by such attributes as setting high but attainable goals, taking responsibility for task accomplishment, and the education and/or experience of the individual. This ability can be easily viewed on a continuum: At one end are those subordinates who are perhaps new to the job and neither willing nor able to take responsibility for task accomplishment; at the other extreme are those who are, say, more experienced and confident, and thus both willing and able to take responsibility for task accomplishment. As the maturity level of followers grows, from one of being inexperienced to experienced and capable, this theory would maintain that the leader’s style can and should change and adapt as well. For example, a police supervisor with a new subordinate who is nowhere ready to perform the demands of the job – his maturity level is low, and he is unable to do the job – would be most effective if employing an style of leadership that is more authoritarian, providing more close supervision, one-way communication supervision and telling what how, what, and when they will perform certain tasks. Conversely, an employee who is “mature,” has the willingness and ability to perform the job, calls for a leadership style that is more hands-off, with the leader delegating more responsibility and allowing the subordinate more decision making authority. The onus of this style of leadership is that it is dependent on leaders to diagnose follower ability and then adjust their leadership style to the given situation. Doing so is often easier said than done.

Making A Police Organization “Great”

Another approach to successful leadership, in the form of a book that rapidly became desirable reading for many executives, was provided by Jim Collins (2001) in Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap and Others Don’t, which sought to answer the compelling question: Can a good company become a great company and, if so, how? Collins and his team of assistants searched for companies that made a “leap to greatness,” as defined by stock market performance and long-term success; they found 11 companies that met their criteria and spent more than 10 years studying what made them great. Following that, and acknowledging the growing interest in his book by non-business entities, Collins later published a monograph entitled Good to Great and the Social Sectors (Collins 2005) concerning how lessons concerning “greatness” could be modified to fit government agencies. Certainly, much of the success of great police organizations has to do with their leadership.

Collins coined the term Level 5 leader to describe the highest level of executive capabilities (Levels 1 through 4 are highly capable individual, contributing team member, competent manager, and effective leader). Level 5 executives are ambitious, but their ambition is directed first and foremost to the organization and its success, not to personal renown. Level 5 leaders, Collins stressed, are “fanatically driven, infected with an incurable need to produce results” (quoted in Wexler et al. 2007: 7).

Such leaders, Collins found, do not exhibit enormous egos; instead, they are self-effacing, quiet, reserved, even shy. Perhaps this has to do with the nature of their organizations. Unlike business executives, police leaders have to answer to the public; unions and civil service systems further inhibit their power. Therefore, Level 5 leadership in a police organization may involve a greater degree of legislative-type skills – relying heavily on persuasion, political currency, and shared interests to create the conditions for the right decisions to happen (Wexler et al. 2007).

Collins also used a bus metaphor when talking about the transformation from good to great, with leaders first getting the right people on the bus, and the wrong people off the bus and then figuring out where to drive it) (Wexler et al. 2007). Interestingly, Collins emphasized that the true challenges for a leader is not about assembling the right team who will be motivated (the right people will be self-motivated). Rather, putting them in the right seats on the bus is the critical challenge. When police executives are appointed or promoted, they inherit nearly all of their personnel, including poor performers who are unenthusiastic about the organization’s vision and philosophy. Some of these people may be near retirement (about ready to “get off the bus”). Collins believes that picking the right people for the right jobs and getting the wrong people off the bus are critical (Wexler et al. 2007).

This is why performance evaluations are so critical. Unfortunately, however, many police departments still have not created evaluation tools that adequately reflect the work police do. The tendency is to measure what is easy to measure: orderliness (neatness, attendance, punctuality) and conformity to organizational rules and regulations. Until police agencies invest in valid and reliable instruments for measuring the real work of policing, it will remain very difficult to move the nonperformers out of the organization.

Perhaps the most difficult part of achieving greatness is sustaining that greatness. Police chiefs have notoriously short tenure in office. Therefore, in their world, some of Collins’s principles may be particularly important – for example, finding Level 5 leaders who pay close attention to preparing for the next generation of leaders, giving managers authority to make key decisions, sending them to leadership academies and conferences, and encouraging them to think on their own and ask questions. This process is termed succession planning and is discussed below.

Police Administration Evolves: From Beginning To Present-Day

Policing Begins In The USA: The Political Era, 1840s To 1930s

Policing, as it exists today as a full-time career or occupation, began in America in 1844 in New York City, where it was deliberately placed under the control of the city government and city politicians. The American plan required that each ward in the city be a separate patrol district. The process for selecting officers was therefore different as well. City mayors chose the recruits from a list of names submitted by the aldermen and tax assessors of each ward; the mayor then submitted his choices to the city council for approval. Thus, most of the power over the police went to the ward aldermen, rather than to the police executive. Instead, the system allowed and even encouraged political patronage and rewards for friends (Johnson 1981).

Police administration during this era was thus largely a paper tiger; indeed, the New York law providing for the hiring of a chief of police gave no power to the chief in hiring the authorized 800 officers, nor to assign their duties or to fire them (Johnson 1981).

As other municipal police agencies developed in the East, three important issues confronted police administrators: whether the police should be in uniform, whether they should be armed, and whether they should use force. The wearing of a uniform was one of the basic principles of crime prevention – that police officers be visible, and that crime victims cound locate a police officer in a hurry. Furthermore, uniforms would make it difficult for officers to avoid their duties, since it would strip them of their anonymity. However, police officers themselves tended to prefer not to wear a uniform, and some even threatened to sue if compelled to don a uniform. To remedy the problem, New York City officials took advantage of the fact that their officers served four-year terms of office; when those terms expired in 1853, the city’s police commissioners announced they would not rehire any officer who refused to wear a uniform. Thus in 1854 New York became the first American city with a uniformed police force.

A more serious issue was the carrying of arms. At stake was the personal safety of the officers and the citizens they served. Nearly everyone viewed an armed police force with considerable suspicion, however. Eventually, because the new police could hardly withstand attacks by armed assailants, it was agreed that an armed police force was unavoidable (Johnson 1981).

Eventually, the use of force, the third issue, would become necessary and commonplace for American officers. Indeed, the uncertainty about whether an offender was armed perpetuated the need for an officer to rely on physical prowess for survival on the streets. In New York, the police reform board was headed by Theodore Roosevelt. His appointed officers were criticized by disgruntled Tammanyites (corrupt New York City politicians) who favored the political patronage system of hiring police. Roosevelt’s approach violated the American tradition of hiring local boys for local jobs.

Police administrators presided over agencies that had other problems as well. For example, from the onset of professional American policing, there was little or no lateral movement from one department to another; consequently, police departments soon became inbred, and tradition became the most important determinant of police behavior. A major teaching tool was the endless string of war stories the recruit heard, and the emphasis in most departments was on doing things as they had always been done. Innovation was frowned upon, and rookies were taught that things had to remain the same.

Police administrators of the late nineteenth century were also occupied with riots, strikes, parades, and fires. Labor disputes often meant long hours of extra duty for their officers, for which no extra pay was received. The police typically had little empathy or identification with strikers or strikebreakers; therefore the use of the baton to put down riots, known as the “baton charge,” was not uncommon (Richardson 1974).

During the late nineteenth century, large cities gradually became more orderly places. The number of riots dropped. In the post–Civil War period, however, ethnic group conflict sometimes resulted in individual and group acts of violence and disorder, but daily urban life generally became more predictable and controlled. Ethnic and religious disputes were found in many police departments, however. In New York, the Irish officers controlled many hires and promotions, and there were still strong political influences at work. George Walling, an NYPD superintendent for eleven years, lamented after his retirement that he had largely been just a figurehead. Politics were played to such an extent that even nonranking patrol officers used political backers to obtain promotions, desired assignments, and transfers (Richardson 1974).

Partly because of their initial closeness to politicians, police corruption also surfaced at this time. Corrupt officers wanted beats close to the gamblers, saloonkeepers, madams, and pimps – people who could not operate if the officers were “untouchable” or “100% coppers” (Richardson 1974: 55–56). Political pull for corrupt officers could work for or against them; the officer who incurred the wrath of his superiors could be transferred to the outposts, where he would have no chance for financial advancement. While serving as police commissioner in New York, Theodore Roosevelt frequently made clandestine trips to the beats to check his officers. Any malingerers found in the saloons were summoned to headquarters in the morning (Richardson 1974).

The Reform Era And Attempts To End Political Patronage: 1930s To 1980

During the early twentieth century, reformers sought to reject political involvement of the police, and civil service systems were created to eliminate patronage and ward influences in hiring and firing police officers. In some cities, police chiefs did not permit their officers to live in the same beat they patrolled in order to isolate them as completely as possible from political influences. Police departments became one of the most autonomous agencies in urban government. Policing also became a matter viewed as best left to the discretion of police executives, and agencies became highly centralized, with the sole goal of controlling crime. Melding with the community was more eschewed, and any non-crime activities officers were required to perform was considered as “social work.” Thus the reform era (also termed the professional era) of policing would soon be in full bloom.

Further removing policing from its earlier people-oriented, decentralized nature (and probably reducing job satisfaction in the process), the management-oriented scientific theory of administration was advocated by Frederick Taylor during the early twentieth century. Taylor first studied the work process, breaking down jobs to their basic steps and emphasizing time and motion studies, all with the goal of maximizing production. From this emphasis on production and unity of control flowed the notion that police officers were best managed by a hierarchical pyramid of control. Police leaders routinized and standardized police work; officers were to enforce laws and make arrests whenever they could, and discretion was limited as much as possible. When special problems arose, special units (for example, vice, juvenile, drugs, tactical) were created rather than assigning problems to patrol officers.

August Vollmer became a major force in the development of professional policing and its administration – but in a positive and prescient manner. In April 1905 at age 29, Vollmer became the town marshal in Berkeley, California (Vollmer 1933). Vollmer was the first chief to order his men to patrol on bicycles. He then persuaded the City Council to purchase a system of red lights, which hung at street intersection and served as an emergency notification system for police officers. He also began to question the suspects he arrested concerning their methods, and became convinced of the value of scientific knowledge in criminal investigation. Vollmer’s most daring innovation came in 1908: the idea of a police school. The first formal training program for police officers in the country drew on the expertise of university professors as well as police officers (Peak 2012).

In 1916, Vollmer hired a professor of pharmacology and bacteriology to run the department’s crime laboratory, and by 1917 the entire patrol force became the first to operate out of automobiles; in 1918, he began to hire college students as part-time officers and to administer a battery of tests to all applicants. Vollmer also advocated the idea that the police should function as social workers, doing more than merely arresting offenders while seeking to prevent crime (Peak 2012).

The Crime Fighter Image

The 1930s marked an important turning point in the history of police reform. O. W. Wilson emerged as the leading authority on police administration, and the crime fighter image gained popularity. Wilson, a student of Vollmer, followed in his mentor’s footsteps by advocating efficiency within the police bureaucracy through scientific techniques. While chief of police in Wichita, Kansas, Wilson conducted the first systematic study of one-officer squad cars. A major contribution was the publication of Wilson’s (1950) classic textbook, Police Administration, which set forth ideas regarding police deployment, discipline, and organizational structure. Wilson would later teach at UC Berkeley, and in 1947 he founded the first professional School of Criminology. Wilson became the principal architect of the police reform strategy.

Police As The “Thin Blue Line”: Chief William H. Parker

The movement to transform the police into professional crime fighters perhaps found its staunchest champion in William H. Parker, who became the Los Angeles police chief in 1950. His greatest success, typical of the new professionalism, came in administrative reorganization. The command structure was simplified, and rigorous selection and training of personnel became a major characteristic of the LAPD – which became the model for reform across the nation (Johnson 1981). Parker conceived of the police as a thin blue line, protecting society from barbarism and Communist subversion. He viewed urban society as a jungle, needing the restraining hand of the police; only the law and law enforcement saved society from the horrors of anarchy. The police had to enforce the law without fear or favor – with few restrictions on police methods such as wiretaps and searches and seizures (Richardson 1974).

The Community Problem-Solving Era

Until the 1970s, there were few outside, scientific inquiries concerning police functions and methods, for two reasons. First was a tendency on the part of the police to resist outside scrutiny and research into their operations. Many police administrators perceived a threat to their career and to the image of the organization, as well as a concern about the legitimacy of the research itself. Second, few people in policing perceived a need to challenge traditional methods of operation, and police methods were not even open to debate.

However, the turmoil of the 1970s compelled the police to open their doors to the outside world and allow academics to study their functions. This turmoil – which centered on the raging Vietnam War, race relations, and equal opportunity – included not only riots, protests, and sit-ins, but also such brutal police actions as those that occurred in Chicago in 1968 during the Democratic National Convention; people were served a nightly television display of police using clubs and gas to control rioters. Furthermore, five national commissions were established during the 1960s and 1970s, some of which lamented the “lawlessness” of the police and their lack of professionalism

In the early 1970s it was suggested that the performance of patrol officers would improve more by using job redesign based on certain motivations. This suggestion later evolved into a concept known as “team policing,” which sought to restructure police departments, improve police-community relations, enhance police officer morale, and facilitate change within the police organization. Its primary element was a decentralized neighborhood focus to the delivery of police services. Officers were to be generalists, trained to investigate crimes and basically attend to all of the problems in their area, with a team of officers being assigned to a particular neighborhood and responsible for all police services in that area – the community problem-solving era.

There were other developments for the police during the late 1970s and early 1980s. Foot patrol became more popular, and many jurisdictions even demanded it. Foot patrol was found to produce a significant increase in public satisfaction with police service, a reduction of perceived crime problems, and an increase in the perceived level of safety of the neighborhood (Police Foundation 1981).

In addition, research conducted during the 1970s suggested that information could help police improve their ability to deal with crime. These studies created new opportunities for the police to understand the increasing concerns of citizens’ groups about disorder (e.g., gangs, prostitutes) and to work with citizens to do something about it. Police executives discovered that when they asked citizens about their priorities, citizens often provided useful information.

Simultaneously, problem-oriented policing was being tested in several cities. These studies found that patrol officers have the capacity to do problem solving successfully and can work with citizens and other agencies to solve problems when given more autonomy and training to analyze the underlying causes of problems and to find creative solutions.

Thus policing moved into the current community era, with a renewed emphasis on community collaboration for many police tasks and crime prevention. Administrators organize their agencies so as to be more decentralized, pushing decision making to the lower levels of the organization.

Local Police Administrators: Police Chiefs And Sheriffs

The chief of police (sometimes known as commissioner or superintendent) is generally considered to be one of the most influential and prestigious persons in local government. Indeed, people in this position often amass considerable power and influence in their jurisdiction. Mayors, city managers and administrators, members of the agency, labor organizations, citizens, special-interest groups, and the media all have differing role expectations of the chief of police that often conflict.

The mayor or city manager likely wants the chief of police to promote departmental efficiency, reduce crime, improve service, and so on. Others appreciate the chief who simply keeps morale high and citizens’ complaints low. The mayor also expects the chief to communicate with city management about police-related issues and to be part of the city management team; to communicate city management’s policies to police personnel; to establish agency policies, goals, and objectives and put them in writing; to develop an administrative system for managing people, equipment, and the budget in a professional and businesslike manner; to administer disciplinary action consistently and fairly when required; and to select personnel whose performance will ably and professionally promote the organization’s objectives.

Members of the agency also have expectations of the chief executive: to be their advocate, supporting them when necessary and representing the agency’s interests when dealing with judges and prosecutors who may be indifferent or hostile. Citizens tend to expect the chief of police to provide efficient and cost-effective police services while keeping crime and tax rates down (often an area of built-in conflict) and preventing corruption and illegal use of force. Special-interest groups expect the chief to advocate policy positions that they favor. Finally, the media expect the chief to cooperate fully with their efforts to obtain fast and complete information on crime.

Qualifications for the position of police chief vary widely, depending on the size of the agency and the region of the country. Level of education is commonly found to be an important consideration; today, many agencies require a college education plus several years of progressively responsible police management experience. Police chief executives also need several important management skills, perhaps chief among them being the ability to motivate and control personnel and to relate to the community.

Regarding their hiring, cities must often decide whether it would be better to promote someone from within the ranks or hire from outside (perhaps using the assessment center process, described below). Both approaches have advantages and disadvantages. For example, internal candidates would be better known to personnel within the agency and other agencies of criminal justice (e.g., prosecuting attorney) and possibly the governing board. Conversely, one who is brought in from the outside may have new knowledge, skills, and abilities learned and/or practiced at other city or county venues, less “baggage” than what one might accumulate in the home city or county, and so on.

The position of sheriff has a long tradition, rooted in the time of the Norman conquest of England (in 1066), and it played an important part in the early law enforcement activities of colonial America. Because of the diversity of sheriff’s offices throughout the country, it is difficult to describe a typical sheriff’s department; these offices run the gamut from the traditional, highly political, limited-service office to the modern, fairly nonpolitical, full-service police organization. It is possible, however, to list functions commonly associated with the sheriff’s office: serving civil processes (e.g., divorce papers, liens, evictions, garnishments and attachments, extradition and transportation of prisoners); collecting certain taxes and conducting real estate sales for the county; performing routine order-maintenance duties by enforcing state statutes and county ordinances; performing traffic and criminal investigations; serving as bailiff of the courts; maintaining and operating the county jail.

Sheriffs are elected in all but two states (Rhode Island and Hawaii; note, however, that in some consolidated jurisdictions, such as Miami–Dade county, Florida, sheriffs are also appointed); thus, they tend to be aligned with a political party. As elected officials, sheriffs are important political figures and, in many rural areas, represent the most powerful political force in the county. As a result, sheriffs are far more independent than appointed municipal police chiefs, who can be removed from office by the mayors or city managers who appoint them. However, because they are elected, sheriffs receive considerable media scrutiny and are subject to state accountability processes.

Because of this electoral system, it is possible that the only qualification for the office is the ability to get votes. In some areas of the country, the sheriff’s term of office is limited to one 2-year term at a time (a sheriff cannot succeed himself or herself); thus, the office has been known to be rotated between the sheriff and undersheriff. In most counties, however, the sheriff has a 4-year term of office and can be reelected.

The sheriff enjoys no tenure guarantee, although one study found that sheriffs (averaging 6.7 years in office) had longer tenure in office than chiefs of police (5.4 years). The politicization of the office of sheriff can result in high turnover rates of personnel who do not have civil service protection. The uncertainty concerning tenure is not conducive to long-range (strategic) planning. Largely as a result of the political nature of the office, sheriffs tend to be older, less likely to have been promoted through the ranks of the agency, and less likely to be college graduates and to have specialized training than police chiefs. Research has also found that sheriffs in small agencies have more difficulty with organizational problems (field activities, budget management), and that sheriffs in large agencies find dealing with local officials and planning and evaluation to be more troublesome (Hayes 2001).

What Police Executives Do: Essential Functions

Finally, to better understand what police leaders do on a more day-to-day basis, adapting Henry Mintzberg’s (1975) general model of chief executive officers (CEOs) to police work is instructive. Included in the model are three major roles or categories (interpersonal, informational, decision maker) and several subcategories, which allows for grouping and delineating the police executives’ occupational roles.

The Interpersonal Role

The interpersonal role includes figurehead, leadership, and liaison duties. As a figurehead, the CEO performs various ceremonial functions. Examples include riding in parades and attending other civic events; speaking before school and university classes and civic organizations; meeting with visiting officials and dignitaries; attending academy graduation and swearing-in ceremonies and some weddings and funerals; and visiting injured officers in the hospital. The CEO performs these duties simply because of his or her position within the organization; the duties come with being a figurehead.

The leadership function requires the CEO to motivate and coordinate workers while resolving different goals and needs within the department and the community. For example, a chief or sheriff may have to urge the governing board to enact a code or ordinance that, whether popular or not, is in the best interest of the jurisdiction; CEOs also provide leadership in such matters as bond issues (e.g., to raise money for more officers or to build new stationhouse facilities) and advise the governing body on the effects of proposed ordinances.

The role as liaison is performed when the CEO of a police organization interacts with other organizations and coordinates work flows. Here, the police chief or sheriff might meet informally each month to discuss common problems and strategies. They might also do the same with representatives of the courts, the juvenile system, and other criminal justice agencies.

The Informational Role

The informational role is composed of monitoring/inspecting, dissemination, and spokesperson functions. Monitoring/inspecting involve the CEO constantly looking at the workings of the department to ensure that things are operating smoothly by “roaming the ship,” sitting in on staff meetings, and generally being a part of efforts that discuss agency problems and functions.

The dissemination tasks involve getting information to members of the department. This may include memorandums, special orders, general orders, and policies. The spokesperson function is related, but it is more focused on getting information to the news media. News organizations are in a competitive field in which scoops and deadlines and the public’s right to know are all-important. Still, the media must understand those occasions when a criminal investigation can be seriously affected by premature or overblown coverage.

The Decision-Maker Role

As a decision maker, the police executive serves as an entrepreneur, a disturbance handler, a resource allocator, and a negotiator. As entrepreneur, the CEO must sell ideas to the governing board or the department. Ideas might include new computers or a new communications system, a policing strategy (such as community-oriented policing and problem solving), or different work methods, all of which are intended to improve the organization.

As a resource allocator, the CEO must have a clear idea of the budget and what the priorities are and must listen to citizen complaints and act accordingly. For example, ongoing complaints of motorists speeding in a specific area will result in a shifting of patrol resources to that area or neighborhood. Finally, as a negotiator, the police manager resolves employee grievances and sits as a member of the negotiating team for labor relations.

Middle Managers And Supervisors

Captains And Lieutenants

Leonhard Fuld, one of the early progressive police administration researchers, said in 1909 that the captain is one of the most important officers in the organization. Fuld believed that the position had two broad duties – policing and administration. The captain was held responsible for preserving the public peace and protecting life and property within the precinct. Fuld defined the captain’s administrative duties as being of three kinds: clerical, janitorial, and supervisory (1909).

Although every ranking officer in the police department exercises some managerial skills and duties, here we are concerned with the managers to whom first-line managers report, for they generally are unit commanders. In a mid-sized or large police agency, a patrol shift or watch may be commanded by a captain. The lieutenants, reporting to the captain in the normal hierarchy, may assist the captain in running the shift, but when there is a shortage of sergeants as a result of vacations or retirements, the lieutenant may assume the duties of a first-line manager. In some respects, the lieutenant’s position in some departments is a training ground for future unit commanders (the rank of captain or higher).

In a medium-sized or large police organization, captains devote a substantial amount of time coordinating their units’ activities with those of other units and overseeing the operation of their units. At the same time, however, captains also perform supervisory duties (e.g., writing reports, reviewing incoming complaints and subordinates’ reports, ensuring that subordinates comply with general and special orders, completing employees’ performance evaluations, serving on promotional and hiring boards). Whereas a sergeant or lieutenant may be supervising individual officers, a captain is more concerned with unit activities and the overall performance of the officers under his or her command. Furthermore, as can be seen from this list, the unit commander functions to some extent like a police chief or sheriff, but on a smaller scale. The chief performs these functions for the total department, while the unit commander is concerned with only one unit (Peak et al. 2010).

Lieutenants, as the companion middle-manager to captains, perform some tasks that are purely administrative in nature but typically involve more of the day to day activities that are related to patrol operations: preparing duty rosters, conducting roll call, preparing various reports, and maintaining time sheets. At times, lieutenants may also perform duties that resemble those that are supervisory in nature, such as assisting in supervising or directing the activities of the unit, ensuring that departmental and governmental policies are followed, reviewing the work of individuals or groups in the section, responding to field calls that require an on-scene commander, and reviewing various reports. These functions include overseeing officers and sergeants to ensure that different tasks are completed.

First-Line Supervisors: The Patrol Sergeant

As indicated above, another very important level of leadership – indeed, to the majority of police, who are rank-and-file officers, the most important leadership level – is that of patrol sergeant. Officers are often told that it is best to rotate into different assignments before testing for sergeant to gain exposure to a variety of police functions and managers. The promotional system, then, favors well-rounded officers. As with the chief executives’ hiring process, an assessment center will provide candidates with valuable training and testing experience. Other factors that might come into play as part of the promotional process include education and training, years of experience, supervisory ratings, psychological evaluations, and departmental commendations (Peak 2012).

Police administrators understand that a good patrol officer is not automatically a good supervisor. Because supervisors are promoted from within the ranks, they are often placed in charge of their friends and peers. Longstanding relationships are put under stress when a new sergeant suddenly has official authority over former equals. Leniency or preferential treatment often is expected of new sergeants by their former peers. A new supervisor therefore must go through a transitional phase to learn how to exercise command and get cooperation from subordinates.

The supervisor’s role, put simply, is to get his or her subordinates to do their very best. This role involves a host of actions, including communicating, motivating, leading, team building, training, appraising, counseling, and disciplining. They are in close proximity to their subordinates, the patrol officers, and thus can determine each subordinate’s strengths and weaknesses, and ensure that each officer’s conduct coincides with the organization’s mission, values, goals, and objectives. Supervisors must be good communicators, disseminating information to subordinates, ensuring that general and special orders from captains and lieutenants are followed, reviewing all officers’ offense and traffic crash reports, listen to and assist officers with personal or professional problems, respond to officers’ calls for service, keep superiors apprised of ongoing situations and problems, and be able to interpret laws and policies for subordinates.

Obtaining The Best: The Assessment Center

In order to obtain the most capable people for police chief executive positions (as well as for middle-management and even supervisory positions), the assessment center method has proved to be an efficacious means of hiring and promoting personnel. (Note: Sheriffs are normally elected, not hired or promoted into their position; thus, the assessment center approach is of little use for that position.)

After developing a job description which lists responsibilities and skills for the position to be filled, then each candidate’s abilities and skill levels should be evaluated, using one or more of the following techniques: interviews; psychological tests; in-basket exercises; management tasks; group discussions; role-playing exercises such as simulations of interviews with subordinates, the public, and news media; fact-finding exercises; oral presentation exercises; and written communications exercises.

During each exercise, several assessors or raters analyze each candidate’s performance and record some type of evaluation; when the assessment center process ends, each rater submits his or her rating information to the person making the hiring or promotion decision. Typically selected because they have held the position for which candidates are now vying, assessors must not only know the types of problems and duties incumbent in the position, but also should be keen observers of human behavior.

Although obviously much more expensive and labor-intensive to perform, the assessment center can serve to avoid many of the errors of alternative methods of selecting police leaders and is highly recommended for jurisdictions who literally wish to “test” their candidates and thus make the best choice.

Evaluating Police Administrators

How good is a municipal police chief or county sheriff? The answer to that question probably depends on whom one asks. To some, the police chief executive’s arrival is the best thing that ever happened to the area; to others, he or she is the worst thing. One reason for the differing viewpoints is that people’s criteria for evaluating their chief or sheriff will vary. Therefore, rating the CEO’s performance in this complex job involves several potential “traps.” CEOs are human; they do make mistakes, but citizen perceptions of them and their performance are often wrong. Therefore, it is difficult to assess accurately how the CEO is performing; no litmus test or simple fill-in-the-boxes exercise exists. Several broad, general guidelines can be applied, however, when evaluating these CEOs.

Inappropriate Criteria

Some criteria that are generally inappropriate for evaluating CEOs include such considerations as: popularity in the department (the longer the CEO’s tenure, the greater the likelihood that people both inside and outside the department will have something to gripe about); departmental morale (morale is a fragile thing, and most organizations have chronic and notorious complainers; thus, the morale of a department is not necessarily the result of the CEOs leadership); a rising crime rate (a variety of social and economic factors influence community crime levels; therefore, to blame the chief executive for the crime rate is inappropriate if not unfair – given, however, that the chief executive should know how and when to develop programs and strategies to combat rising crime rates); single incident or issue (a police beating or shooting of a citizen can cause a loud hue and cry and even calls for the chief’s head; however, more often a multidimensional review of the chief’s total performance should be made, and the firing of the chief does not ensure that the basic problem causing the upheaval will be eliminated).

Appropriate Criteria

A police executive’s evaluation should focus only on qualities, characteristics, and behavior required to perform the job. Honesty and integrity are probably the chief’s most important qualities, followed by leadership effectiveness. The direction of the department, its commitment to professional and ethical standards, and its basic values emanate from the chief’s leadership role. The chief’s ability to motivate people without shoving them and to inspire people both inside and outside the department should also be considered.

Any assessment of the chief executive must consider leadership effectiveness. The chief’s ability to be a good follower and take a subordinate position to the mayor and city manager/council is also important. It is important that the chief know where the lines are drawn, when it is time to quit leading and start following.

CEOs manage a significant amount of resources – human and financial, equipment, and physical facilities. CEOs must make timely and responsible decisions, as well as realize the impact and legal ramifications of those decisions. The chief executive must also delegate authority and decision making to others rather than taking on too much, which often results in a sluggish operation. Finally, a chief executive must be innovative and creative in thinking. Today’s CEO must be willing to keep up with the challenges facing law enforcement and need to move the agency into a new era of research, experimentation and risk-taking – to become a “learning organization.”

Several other areas of the chief executive’s performance must also be evaluated. The first relates to departmental values: do the department’s values reflect a commitment to the rights of individuals and its employees? Does the CEO manage force carefully and aggressively to ensure that the public is not subjected to unlawful or unwarranted physical force by police? Does the CEO require the agency to have clear policies, rules, and procedures to guide employee? Are those directives are constantly updated and enforced fairly and consistently? Has the CEO introduced or implemented crime strategies to make the community safer?

The labor climate of the organization is an especially difficult area for today’s police executive; civil service, unions, appeal boards, the courts, and the changing profile of today’s police officer have made managing labor relations a constant challenge.

Finally, the CEO’s understanding of where the department stands with the community should be evaluated. No other sector of government in our society has more frequent and direct contact with the public than the police.

The Future Of Police Management: Succession Planning

Soon the administration, management, and supervision of police agencies could be in a crisis stage unless measures are taken in the near future to prepare for what is coming: the current aging, turnover, and retirement of baby boomers and other generational employees. Today an essential part of every chief’s job is to prepare colleagues in the organization for the next advance in their careers; indeed, today the mark of a good leader is the ability to ensure a ready supply of capable leaders for the future.

Thorough preparation of successors can help a chief establish an important legacy – one that will sustain the improvements and progress that have been made, offer opportunities for mentoring, and instill the importance of the organization’s history.

Chiefs need to take a long view and look at succession planning and leadership development as a continuous process that changes the organizational culture. To provide the ongoing supply of talent needed to meet organizational needs, chiefs should use recruitment, development tools (such as job coaching, mentoring, understudy, job rotation, lateral moves, higher-level exposure, acting assignments, and instructing), and career planning (Davis and Hanson 2006).

Organizations may already have a sufficient pipeline of strong leaders – people who are competent in handling the ground-level, tactical operations but who are not trained in how to look at the big picture. While not everyone can excel at both levels of execution, efforts must definitely be made to help prospective leaders develop a broader vision – as one author put it, prepare employees to take on broader roles and “escape the silos” (Ready 2004: 93). To develop police leaders who do not see the world in zero-sum terms but instead can appreciate the bigger picture requires people to leave their comfort zones and to offer them challenging assignments in different roles (Ready 2004).

A number of excellent police promotional academies and management institutes exist for developing chief executives, middle managers, and supervisors in the kinds of desired skills described above. In addition, agencies can provide skill development opportunities by having those persons with leadership potential do such things as plan an event, write a training bulletin, update policies or procedures, conduct training and research, write a proposal or grant, counsel peers, become a mentor, write contingency plans, and so forth. Meanwhile, the individual can lay plans for the future through such activities as doing academic coursework, participating in and leading civic events, attending voluntary conferences and training sessions, reading the relevant literature, studying national and local reports, guest lecturing in college or academy classes, engaging in research, and so on (Michelson 2006).

With today’s leadership theory holding that law enforcement executives should adopt a participative management style, also known as democratic leadership, except when emergencies arise, an autocratic management style that includes public criticism can cause resentment among subordinates rather than a sense of teamwork or a spirit of cooperation. This style may also inhibit the development of future leaders and undermine the cooperative leadership process. Leadership is learned behavior, and new leaders can be developed through properly designed leadership experiences (Hernez-Broome and Hughes 2004).

Bibliography:

- Blake RR, Mouton JS (1962) The developing revolution in management practices. J Am Soc Train Dir 16:29–52

- Collins J (2001) Good to great: why some companies make the leap.. .and others don’t. HarperCollins, New York

- Collins J (2005) Good to great and the social sectors: a monograph to accompany good to great. HarperCollins, New York

- Davis E, Hanson E (2006) Succession planning: mentoring future leaders. Police Executive Research Forum, Washington, DC

- Fuld FL (1909) Police administration. G. P. Putnam’s Sons, New York

- Hayes C (2001) The office of sheriff in the United States. Prison J 74:50–54

- Hernez-Broome G, Hughes RL (2004) Leadership development: past, present, and future. Hum Resour Plan 27(1):24–32

- Johnson DR (1981) American law enforcement history. Forum Press, St. Louis

- Katz R (1974) Skills of an effective administrator. Harv Bus Rev 52(5):90–102

- Michelson R (2006) Succession planning for police leadership. Police Chief 16–22

- Mintzberg H (1975) The manager’s job: Folklore and fact. Harv Bus Rev 53(4):49–61

- Peak KJ (2012) Policing America: challenges and best practices, 7th edn. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River

- Peak KJ, Gaines LK, Glensor RW (2010) Police supervision and management: in an era of community policing, 3rd edn. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River

- Police Foundation (1981) The Newark foot patrol experiment. Police Foundation, Washington, DC

- Ready DA (2004) How to grow leaders. Harv Bus Rev 82(12):92–100

- Richardson JF (1974) Urban policing in the United States. Kennikat Press, London

- Shakespeare W (1597) Henry IV, Part II, Act 3

- Vollmer A (1933) Police progress in the past twenty-five years. J Crim Law Criminol 24:161–75

- Wexler C, Wycoff MA, Fischer C (2007) Good to great: application of business management principles in the public sector. Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, Washington, DC, Police Executive Research Forum, 5

- Wilson O (1950) Police administration. McGraw-Hill, New York

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.