This sample Situational Action Theory Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

This research paper introduces Situational Action Theory (SAT) and its key arguments:

Crimes are moral actions. There are many different types of actions that may constitute a crime, but what they all have in common is that they break a rule of conduct (stated in law) about what is the right or wrong thing to do (or not to do). What distinguish crime is thus not that they are a particular kind of action but that they are acts the breach rules of conduct (stated in law) and, therefore, need to be studied and explained as such.

People are the source of their actions, but the causes of their actions are situational. To explain the causes of acts of crime we need to understand the situational factors and processes that move people to break rules of conduct (stated in law). People are different and so are also the settings (environments) to which they are exposed. Acts of crime (particular acts of crime) occur when particular kinds of people (person propensities) encounter particular kinds of settings (environmental inducements) creating specific kinds of interactions that make people see certain action alternatives and make certain choices.

Social and developmental factors and processes are best studied and explained as causes of the causes. To explain the role of social and developmental factors and processes in crime causation, we need to understand how they (as causes of the causes) affect people’s crime propensities and how they impact settings (environments) levels of criminogeneity and how they influence the spatiotemporal convergence of crime prone people and criminogenic settings (creating the interactions that may result in acts of crime or certain types of acts of crime).

Situational Action Theory: Background And Main Aims

Situational Action Theory (SAT) aims to explain why crime happens and the role of social and developmental factors and processes in crime causation (e.g., Wikstrom 2006, 2010; Wikstrom et al. 2012, pp. 3–43). It was specifically designed to overcome some recurrent problems in criminological theorizing such as the unclear definition of crime (i.e., the ambiguity about what a theory of crime aim to explain), the lack of a satisfactory action theory (i.e., the poor understanding of what it is that moves people to engage in acts of crime), and the poor integration of levels of explanation (e.g., Wikstrom 2010, pp. 212–216; Wikstrom et al. 2012, pp. 3–10). The argument is not that all criminological theories fail on all these points, but it is just that they generally fail on one or more of these points.

SAT seeks to integrate key insights from main person and environment-oriented criminological theories and research, and relevant social and behavioral science theories and research more generally, within the framework of an adequate action theory. SAT advocate an analytical criminology, a criminology that focuses on the identification and detailing of the key mechanisms involved in crime causation rather than the production of lists of statistically relevant correlates and predictors (often referred to as risk factors) of which most, at best, are likely to be only markers or symptoms and, therefore, lack any causal relevance (e.g., Wikstrom 2006, pp. 66–69, 2011, pp. 53–60).

Basic Assumptions About Human Nature And Social Order

Situational Action Theory is based on the key assumptions that humans are essentially rule-guide actors and that social order is fundamentally based on people’s adherence to shared rules of conduct. People vary in their personal morals (personal rules of conduct) and settings vary in their moral norms (shared rules of conduct). A personal moral rule is held and enforced (through the process of self-control) by the actor, while a moral norm is held and enforced (through the process of deterrence) by (significant) others. Explaining human action (such as acts of crime) requires understanding how people’s actions are influenced by the interplay between personal morals and perceived moral norms of the setting (environment), a problem that has been largely ignored in criminological theory.

SAT assert that humans have agency (powers to make things happen) but that they exercise agency (i.e., express their desires (needs) and their commitments and respond to frictions) within the constraints of rule-guided choice. The theory acknowledges that there are elements of predictability (habit) and “free will” (deliberation) in people’s choices. Explaining human action (such as acts of crime) requires an understanding of the role of agency (how it works) within rule-guided choice, a problem that has seldom (if at all) been treated in criminological theory.

Crime As Moral Actions

Criminological theories rarely specify or clearly analyze what it is they aim to explain. This is an important common omission since an explanation has to explain something. Without clearly defining what it is that is to be explained, it is difficult to unambiguously identify putative causes and suggest plausible causal processes that may produce the effect under study (e.g., acts of crime). A cause has to be a cause of something, and what that something is determines possible causes (and relevant causal processes).

Situational Action Theory argues that crime is best analyzed as moral actions. SAT defines morality as value-based rules of conduct about what is the right or wrong thing to do (or not to do) in a particular circumstance. Crime is an act that breaks a rule of conduct stated in law (rules that may be quite general or quite specific). What defines crime is thus not any particular type of action but the fact that carrying out a particular action (or refraining from carrying out an action) in a particular circumstance is regarded as breaching a rule of conduct (stated in the law).

Any particular action can, in principle, be defined as a crime, and there are variations over historic time and between places (e.g., countries) in what kinds of action are regarded as crime. Moreover, specific actions, like hitting or even shooting another person, may be considered crimes in some circumstances but not in others.

The advantage of conceptualizing crime as breaches of rules of conduct (stated in law) is that it makes a general theory of crime possible by focusing on what all kinds of crime, in all places, at all times, have in common, namely, the rule-breaking. What is to be explained by a theory of crime causation is thus why people (follow and) breach rules of conduct stated in law. A theory of crime causation may be regarded as a sub-theory of a more general theory of moral action. The law is just one of many sets of rules of conduct that guide people’s action (e.g., Ehrlich [1936] 2008). The law is no different from other sets of rules of conduct; in fact, the law may be regarded as a special case of rules of conduct more generally. Explaining why people follow and break the rules of law is, in principle, no different from explaining why people follow and break rules of conduct more generally.

Analyzing crime as moral action does not imply a “moralistic” approach (no judgement whether existing laws are good or bad, just or unjust, needs to be made). However, SAT does not assume moral relativism (i.e., that all moral rules are equally likely to emerge). Common moral rules may be grounded in human nature and the problem of creating social order (see further Wikstro¨ m et al. 2012, pp. 13–14). The explanation of why we have particular moral norms (and laws) and why people follow or breach moral norms (and laws) is different analytical problems. Importantly, people may breach a moral rule of conduct (stated in law) because they disagree with or care less about the rule (or their ability to exercise self-control is not strong enough to make them adhere to their own personal morals when faced with a temptation or provocation).

The Situational Model: Kinds Of People In Kinds Of Settings

People are different and so are the settings to which they are exposed. When a particular kind of person is exposed to a particular kind of setting, a particular situation (perception-choice process) arises that initiates and guide his or her actions in relation to the motivations he or she may experience. The elements of the situational model are the person (his or her relevant propensities), the setting (its relevant inducements), the situation (the perception-choice process that arises from the exposure of a particular person to a particular setting), and action (bodily movements such as speaking, walking, or hitting). A setting is defined as the part of the environment (objects, persons, events) that is directly accessible to the person through his or her senses (including any media present).

SAT proposes that variations between people in their crime propensity (i.e., the tendency to see, and choose, particular crimes as an action alternative) is essentially a question of their law-relevant personal morality (the extent to which their personal morality corresponds to the various rules of conduct stated in the law) and their ability to exercise self-control (which depends both on dispositional characteristics such as executive functions, and momentary influences such as intoxication and levels of stress – see Wikstro¨ m and Trieber 2007).

People will vary in their propensity to see a particular kind of crime as an action alternative not only depending on their personal moral rules but also depending on their moral emotions. Moral emotions (shame and guilt) attached to violating a particular rule of conduct may be regarded as a measure of the strength with which a person holds that particular rule of conduct. For example, while many people may think it is wrong to steal something from another person, some may feel very strongly about this while others may not. Those who feel less strongly about stealing from others may be regarded as having a higher propensity to perceive such action as an option.

People vary in their ability to exercise self-control (i.e., their ability to act in accordance with their personal morality when it conflicts with a perceived moral norm of a setting). The ability to exercise self-control exerts its influence through the process of choice and is only important in the explanation of crime when a person deliberate over several potent action alternatives, of which at least one involve an act of crime. The concept of self-control in SAT is different from that of self-control in Gottfredson and Hirschi’s (1990) General Theory of crime (see further, e.g., Wikstro¨ m 2010, pp. 228–234). Crucially SAT makes a clear distinction between self-control as situational process (the process by which a person manage conflicting rule guidance) and people’s abilities to exercise self-control.

SAT further proposes that the criminogeneity of a setting depends on its (perceived) moral norms (the extent to which it encourage or discourage the breaking of particular laws in relation to the opportunities a setting provides and the frictions it creates) and their level of enforcement through the process of deterrence (note that if a moral norm encourages the breaking of a particular law, a high degree of its enforcement will be criminogenic). Deterrence is defined as “the process by which the (perceived) enforcement of a setting’s (perceived) moral norms, by creating concern or fear of consequences, succeeds in making a person adhere to the moral norms of the setting even though they conflict with his or her personal moral rules.”

Key Situational Factors And The Situational Process

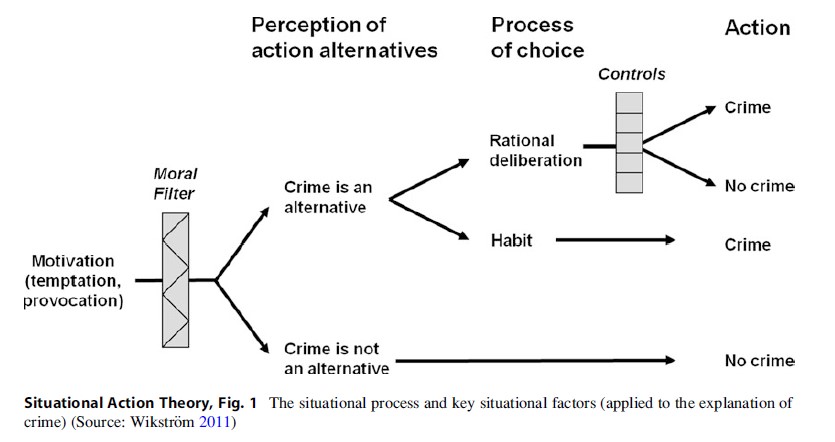

The cornerstone of Situational Action Theory is that people’s actions ultimately is a consequence of how they perceive their action alternatives and, on that basis, makes their choices when confronted with the peculiarities of a setting. The perception-choice process is crucial for understanding a person’s actions. Perception (the selective information we get from our senses) is what links a person to his or her environment, and choice (the formation of an intention to act in one way or another) is what links a person to his or her actions (see further Wikstrom 2006, pp. 76–84). In contrast to most choice-based theories of action, which focus on how people choose among predetermined alternatives, Situational Action Theory stresses the importance of why people perceive certain action alternatives (and not others) in the first place. Perception of action alternatives thus plays a more fundamental role in explaining actions, such as acts of crime, than the process of choice (which is secondary to perception of action alternatives). The key stages of, and the key situational factors in, the perceptionchoice process, according to SAT, is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Motivation (defined as goal directed attention) is a situational factor that initiates the action process and is an outcome of the interaction between the person (preferences, commitments, sensitivities) and the setting (opportunities, frictions). According to SAT there are two main kinds of motivators; (1) temptations, which are either the outcome of the interaction between (a) a person’s desires (wants, needs) and opportunities to satisfy a desire (want, need) or (b) the outcome of the interaction between a person’s commitments and opportunities to fulfill a commitment (opportunities to satisfy a desire or to fulfill a commitment may be legal or illegal), and (2) provocations, which occur when a friction (an unwanted external interference) causes anger or annoyance towards the perceived source of the friction or a substitute. People vary in their sensitivities to particular kinds of frictions (as a consequence of their cognitive-emotive functioning and life-history experiences).

Motivation is a necessary but not sufficient factor in the explanation of crime. What particular action alternatives a person perceives in relation to a particular motivation (and whether that includes an act of crime) is dependent on the moral filter. The moral filter is defined as “the moral rule-induced selective perception of action alternatives in relation to a particular motivation” and is an outcome of a person’s moral engagement with the perceived moral norms of a setting in relation to a specific motivation. If crime is not among the action alternatives a person perceives, there will be no crime and the process of choice is irrelevant as an explanation of why he or she refrained from committing an act of crime; he or she simply did not see crime as an option.

If an act of crime is among the perceived action alternatives the process of choice will determine whether or not a person will commit (or attempt) an act of crime. SAT distinguishes between two main kinds of processes of choice: habitual (automated) or deliberative processes of choice (in prolonged action sequences the action guidance may drift between habitual and deliberative influences). The important difference between the two processes is that in case of actions (such as acts of crime) committed out of habit, the actor only sees one potent alternative in response to a motivation (temptation or provocation) and act accordingly, while in the case of deliberation there is no predetermined response so the actor has to weigh pros and cons of the different perceived alternatives (a process that may be more or less elaborate dependent on the importance of the choice). There is plenty of evidence for the existence of a dual process of human reasoning of this kind (see, e.g., Evans and Frankish 2009). The neuropsychological basis of SAT’s framework for habitual and deliberate decision making, linking these processes to areas of the brain’s prefrontal cortex which have been associated with separate intuitive and cognitive functions, with particular implications for the role of self-control and emotions in action decisions, has been specifically explored by Treiber (2011).

When people act out of habit, they essentially react (in a stimulus-response fashion) to environmental cues, automatically applying experienced based moral rules of conduct to the peculiarities of a setting, while deliberation involves taking moral rules of conduct into consideration when actively choosing between perceived action alternatives. Habitual action is oriented towards the past, while deliberate action is oriented towards the future. When people act habitually, they routinely apply past experiences to guide current action (i.e., they do what they normally do in the particular circumstance without giving it much thought); when they act deliberately, they try to anticipate future consequences of perceived action alternatives and choose the best course of action. When people act out of habit (only see one causally effective alternative; although they may be loosely aware “in the back of their minds” that there are other alternatives, no such alternative is actively considered), rationality does not come into play (since there is only one potent alternative and, therefore, no weighing of pros and cons of different options) and their actions may even be irrational, that is, people may act in ways they would not consider in their best interest had they deliberated. When people deliberate they aim to be rational (to choose the best option as they see it), but, importantly, this does not necessarily involve an aim to maximize personal advantage (whether maximizing personal advantage is seen as the best option is a question of the actor’s moral judgement). Habitual responses are most likely when people operate in familiar circumstances with congruent rule guidance (i.e., when there is a high level of correspondence between personal morals and perceived moral norms of the setting), while deliberate responses are most likely when people are in unfamiliar circumstances and/or there is a conflicting rule-guidance.

Only in choice processes when people deliberate do they exercise “free will” (although it is a “free will” within the constraints of perceived action alternatives) and are they subject to the influence of their ability to exercise self-control (internal control) or respond to deterrence cues (external controls). If there is no conflicting rule guidance, there is nothing to control, and, hence, in these cases (inner and outer) controls lack relevance for the action taken. A person’s ability to exercise self-control is a relevant factor in crime causation when his or her personal moral rules discourage and the moral norms of the setting encourage an act of crime in response to a motivation. In this case, the extent to which a person can act in accordance with his or her personal morals (i.e., refrain from crime) is dependent on the strength of his or her ability to exercise self-control. Deterrence is a relevant factor in crime causation when a person’s personal morals encourage and the moral norms of a setting discourage an act of crime in response to a motivation. In this case, whether or not a person will carry out an act of crime is dependent on the (perceived) efficacy of the enforcement of the moral norms of the setting.

SAT offer a general explanation of key situational factors and processes involved in crime causation. What may differ in the explanation of different kinds of acts of crime is not the process (the perception-choice process) leading up to the action, but the input to the process, that is, the content of the moral context (the action-relevant moral norms) and a person’s morality (the action-relevant moral values and emotions) which drive the process. For all kinds of crime to happen (e.g., shoplifting, insider trading, rape, or roadside bombing), the actor has to perceive the particular action as a viable alternative and choose to carry out the act. However, the specific moral background (relevant personal morals and moral norms of the setting) which guide whether, for example, an act of shoplifting is perceived as an action alternative may differ from that which guides whether an act of rape is perceived as an action alternative.

The Social Model

Situational Action Theory insists that the causes of crime are situational and that social and developmental factors and processes in crime causation are best studied and analysed as the causes of the causes (of acts of crime). SAT advocates a mechanistic explanation of human action (such as acts of crime). The theory is based on four key propositions (of which the first two refer to the situational model and the subsequent two to the social model):

- Action is ultimately an outcome of a perception-choice process.

- This perception-choice process is initiated and guided by relevant aspects of the person-environment interaction.

- Processes of social and self-selection place kinds of people in kinds of settings (creating particular kinds of interactions).

- What kinds of people and what kinds of environments (settings) are present in a jurisdiction is the result of historical processes of person and social emergence.

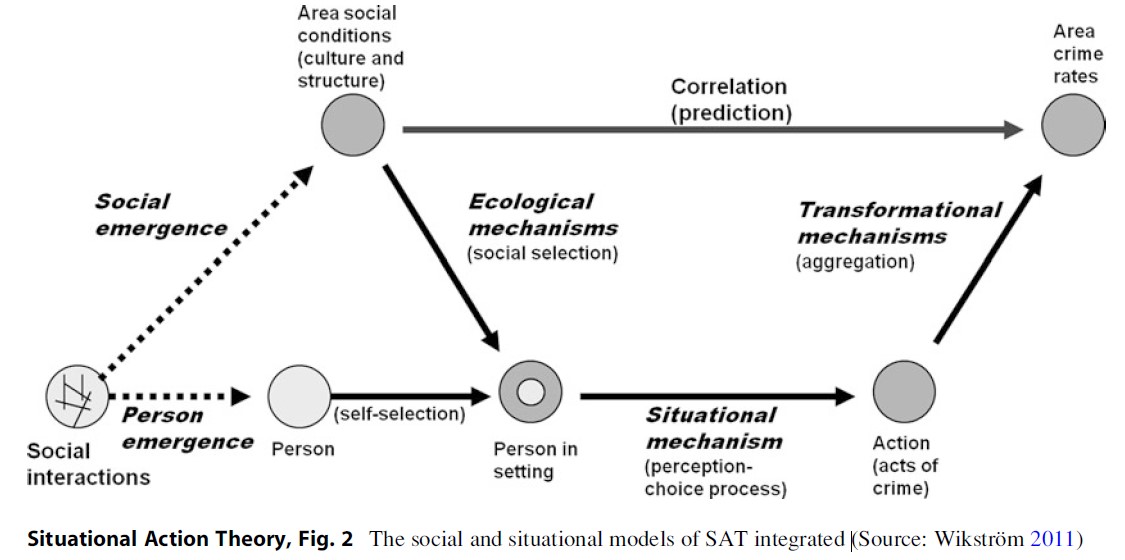

Figure 2 illustrates how the social and situational models are integrated. The key content of the situational model has already been discussed, and the remaining part of this paper will be devoted to a brief outline of the role of processes of emergence and selection in crime causation.

The social model of SAT focuses on the role of historical processes of emergence in the creation of criminogenic environments (social emergence) and crime prone people (person emergence) and contemporaneous processes of self-and social selection that bring together crime prone people and criminogenic settings (creating the situationto which people may respond to motivators by committing acts of crime). The concept of emergence refers to how something becomes as it is (e.g., Bunge 2003). For example, how people acquire a certain crime propensity (personal emergence) or environments acquire a certain criminogeneity (social emergence) as an outcome of processes of social interactions. The concept of selection refers to the contemporaneous socioecological processes responsible for introducing particular kinds of people to particular kinds of settings (and thus creating the situations to which people’s actions are a response).

SAT proposes that psychosocial processes of moral education and cognitive nurturing are of central interest in the explanation of why people develop specific and different crime propensities (i.e., tendencies to see and choose particular crimes as an action alternative) (see further Wikstrom et al. 2012, pp. 31–32). SAT further proposes that socio-ecological processes (e.g., processes of segregation and their social consequences) become of particular interest in the explanation of why particular kinds of moral contexts emerge in particular places at particular times (see further Wikstrom et al. 2012, pp. 2–37).

Why certain kinds of people end up in certain kinds of setting depends on processes of social and self-selection and their interaction. Social selection refers to the social forces (dependent on systems of formal and informal rules and differential distribution of personal and institutional resources in a particular jurisdiction) that encourage or compel, or discourage or bar, particular kinds of people from taking part in particular kinds of time and place-based activities. Self-selection refers to the preference-based choices people make to attend particular time and place-based activities within the constraints of the forces of social selection. What particular preferences people have developed may be seen as an outcome of their life-history experiences. Depending on the circumstances, social or self-selection can be more influential in explaining why a particular person takes part in a particular setting (see further Wikstrom et al. 2012, pp. 37–41).

Analyzing relevant processes of emergence and selection and how they relate help us understand (i) why people develop certain kinds of crime propensities (and why a population in a particular jurisdiction come to have a certain distribution of crime propensities and why some jurisdictions have more crime prone people than others), (ii) why certain places become criminogenic environments (and why there is a certain prevalence and kind of criminogenic environments in a jurisdiction and why some jurisdictions have more criminogenic environments than others), and (iii) why certain contemporaneous selfand social selection processes create particular kinds of crime hot spots (and why the prevalence and kind of crime hot spots vary between different jurisdictions).

Bibliography:

- Bunge M (2003) Emergence and convergence: quantitative novelty and the unity of knowledge. University of Toronto Press, Toronto

- Ehrlich E (1936) 2008. Fundamental principles of the sociology of law. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers

- Evans J, Frankish K (2009) In two minds: dual processes and beyond. Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Gottfredson M, Hirschi T (1990) A general theory of crime. Stanford University Press, Stanford

- Treiber K (2011) The neuroscientific basis of situational action theory. In: Beaver KM, Walsh A (eds) The Ashgate research companion to biosocial theories of crime. Ashgate Publishing Company, Burlington

- Wikstro¨ m P-O (2006) Individuals, settings and acts of crime. Situational mechanisms and the explanation of crime. In: Wikstro¨ m P-O, Sampson RJ (eds) The explanation of crime: context, mechanisms and development. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

- Wikstrom P-O (2010) Explaining crime as moral action. In: Hitlin S, Vaysey S (eds) Handbook of the sociology of morality. Springer, New York

- Wikstrom P-O (2011) Does everything matter? Addressing the problem of causation and explanation in the study of crime. In: McGloin J, Sullivan CJ, Kennedy LW (eds) When crime appears: the role of emergence. Routledge, London

- Wikstrom P-O, Trieber K (2007) The role of self-control in crime causation. Beyond Gottfredson and Hirschi’s general theory of crime. Eur J Criminol 4:237–264

- Wikstrom P-O, Oberwittler D, Treiber K, Hardie B (2012) Breaking rules. The social and situational dynamics of young people’s urban crime. Oxford University Press, Oxford

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.