This sample Social Network Analysis of Urban Street Gangs Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

This research paper synthesizes the current state of network-related research on street gangs around the themes of network structure, network action, and network location. At their core, street gangs are social networks created by the coming together, socializing, and interacting of individuals in particular times and in particular places. The employment of social network analysis has the potential to examine patterns of interaction among gang members and gangs, illuminate structural variation across gangs, and measure the influence of gang networks on individual action. This research paper includes an overview of social network analysis, suggestions and directions for future gang network research, a discussion of limitations, and a vision for how a social network approach to gangs might inform theory, research, and practice.

Introduction

Over the past decade, the field of criminology has increasingly employed both the theoretical and methodological tools of social network analysis (McGloin and Kirk 2010; Papachristos 2011). Although criminology lags behind other disciplines in this network turn, criminologists have applied social network analysis to investigate organized crime syndicates, narcotics trafficking, terrorist organizations, white-collar conspiracies, and adolescent delinquency. But perhaps one of the areas of criminological inquiry most in need of a network-related approach is the study of street gangs.

Street gangs are, if anything, social networks created by the coming together, socializing, and interacting of individuals in particular times and in particular places. Though scholars still heavily debate the definition of what constitutes a gang, virtually all gangs have some element of a group and it is this groupness that is at the heart of this research paper. Street gangs are groups of individuals engaging in activities that are bolstered by group processes, culture, and structures. Social network analysis studies street gangs empirically to examine precise patterns of interaction among individuals and collectivities (see Papachristos 2006). Theoretically gangs operate as unique sociological entities with various structural and interactional manifestations. Research gathers, compares, and analyzes dozens of network properties at the individual, group, and system level, which brings fresh perspectives to old debates. Contemporary social network approaches have the potential to push past criminology’s definitional bulwarks and typologies and reveal how real-life behavior of individuals and groups might inform theory, research, and practice.

This research paper synthesizes the current state of network-related research on street gangs. Rather than simply plod forward in the standard literature review format of “this article says this” and “that article says that,” the aim will be to review research in a way that provides a road map for future lines of inquiry. Specifically, the focus will be on measuring and theorizing street gangs from multiple levels of analysis in order to shed light on a broader range of empirical gang behaviors, structures, and processes. To wit, this research paper is structured around three themes: (1) the structure of gang networks, (2) the actions of gang networks, and (3) the location of gang networks. In the following sections particular attention will be paid to the group nature of gangs as well as the locations and actions of individuals in gangs. This research paper concludes with a brief discussion of the challenges to and limitations of social network analysis and gang research. To begin, the next section provides a brief discussion of social network analysis more generally and proposes its application to street gangs.

Social Network Analysis And Applications To Street Gangs

Social network analysis (SNA) refers to the study of social relationships among sets of actors and, more importantly, the analysis of how the patterns of relationships affect actors’ behaviors (Wasserman and Faust 1994). Unlike traditional regression analyses in which effects are net of other variables (Emirbayer 1997), SNA assumes interdependence rather than independence. Indeed, it is such interdependence that is of analytic interest. Most network studies attempt to (a) analyze and describe the observed structure of relationships among a set of actors and/or (b) investigate how sets of relationships affect actors’ behaviors, actions, opinions, and attitudes. Empirical research has demonstrated the importance of networks on a variety of phenomena such as getting a job, income attainment, political decision making, the diffusion of ideas, and even political revolutions.

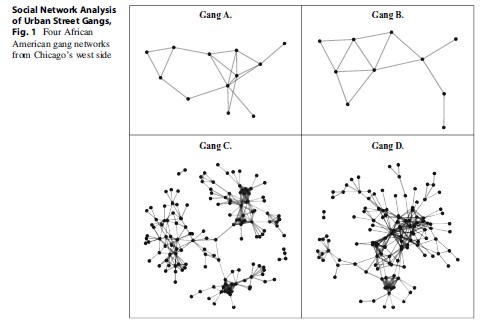

Formally, social network analysis relies on graph theory: mathematical models that capture the pairwise relationships among a specific class of objects (Wasserman and Faust 1994). In graph theoretical terms, a network consists of a set of vertices (V) that represent a bounded set of actors or units and a set of edges (E) that define the relationship among the vertices. Relationships are commonly represented in a square matrix X = xij where xij is the strength of relationship between unit i and unit j (Wasserman and Faust 1994). Edges can be binary indicating the presence of a relationship. Alternatively, edges can be valued measuring the intensity of a relationship, the level of interaction, or any other theoretically sound quantity of a relationship. Ties can also have direction, such that one node sends a tie and another receives it. Sociograms or graphs display networks visually in which nodes depict the vertices and lines depict the edges (see, e.g., Fig. 1).

Conceptually, gangs are clearly social networks. Gangs consist of actors who are tied to each other through group participation and identity, as well as neighborhood, familial, and peer relationships. Furthermore, gangs collectively act in particular moments and places, whether simply hanging out or engaging in gang warfare. Of particular interest for researchers is a gang’s ability to activate ties in order to accomplish certain tasks and the ensuing consequences of those tasks. Figure 1 illustrates this point by mapping the network structures of four African American gangs in Chicago using police observational data. Each node represents a unique individual and each tie represents a non-arrest observation made by the police – sometimes called “field observations” or “field contacts” (see Papachristos et al. 2012a). Each tie is a police observation of two individuals hanging out on a street corner, which is perhaps one of the most fundamental gang activities. By aggregating such information over time and within multiple locations, a network structure emerges representing the patterns of direct and indirect associations among gang members as well as their non-gang companions.

All four of the gangs in Fig. 1 are from the west side of Chicago and are part of larger gang nations that date back to the 1960s. By virtually any survey or qualitative account, all four of these gangs should have the following: a hierarchical structure, formalized sets of rules and regulations, a division of labor, and intricate drug-dealing portfolios. Yet, the patterns of association shown in Fig. 1 reveal that some of the networks deviate from such accounts. Gangs A and B, for example, are smaller in size and less dense than gangs C and D. Moreover, the network structures of gangs A and B look more like ordinary friendship networks and are decidedly not hierarchical. In gang B, triangles of individuals overlap to make up the larger networks; this pattern suggests that the network is comprised of small cliques with overlapping membership as opposed to some formalized division of labor. In contrast, gangs C and D have a starburst type of structure with dense pockets of individuals linked together by one or two ties. These gangs are more centralized, a trait that is especially evident in gang C with a single individual joining three different parts of the graph.

The analysis of gang structures such as those in Fig. 1 can augment more traditional analyses of gangs by comparing structural traits of networks across time and space. A whole range of network measures and statistics – such as density, clustering, and degree distribution (Wasserman and Faust 1994) – can be compared and analyzed across samples of gangs to detect points of variation and similarity. Perhaps more importantly, SNA can examine the structural properties that distinguish a gang from other types of social groups.

A networked approach to gangs requires two related and nested units of analysis: (1) gangs as collectives and (2) gangs as a collection of individual gang members. The questions gang researchers ask rely on the unit of analysis. At the group level, researchers examine organizational structures, gang interactions within larger social spaces, and intragroup relations affecting larger social processes. Individual-level hypotheses center on relations between gang members and gang influence on individual behavior. Research agendas might include (1) how friendship networks within a gang mediate or facilitate violence, (2) the types of relationships from which gang leadership or influence derive, (3) patterns of social status and power among gang members, or (4) the ways in which gang members integrate into lager noncriminal networks (see Papachristos 2006). The remainder of this research paper grapples with some of these hypotheses, which are organized around the themes of network structure, network action, and network location.

Network Structures Of Street Gangs

Though not specified in formal network language, researchers’ conceptualization of street gangs has relied on network concepts and ideas for decades. At the most basic level, gangs can be conceptualized as groups of delinquent individuals who socialize with each other. Rather than a random collection of strangers who happen to share social and geographic space, gangs have a collective identity, a culture, and sense of togetherness. As such, criminologists strive to understand group formation, cultural precepts, or collective processes. Prior research has provided tremendous insight into street gangs’ culture, experiences, and understandings of their group, but has fared less well in explaining the structural variation and scope of street gangs. SNA, however, provides theoretical and methodological tools to evaluate gangs’ organizational structure and participation in those structures.

Organizational Structure

Descriptions of the gangs as organizations range from informal friendships and associations (Fleisher 1999) to formalized corporate bureaucracies (Venkatesh and Levitt 2000). Multiple typologies have emerged attempting to classify gangs according to various organizational or group characteristics. For example, research has debated whether leadership and influence within a gang are vertical (bureaucratic) or horizontal (influence based) (Sanchez-Jankowski 1991). Other typologies differentiate gangs based on certain organizational characteristics such as membership size, meeting regularity, formalized rules and regulations, and gang activities (Bouchard and Spindler 2010; Pyrooz et al. 2012). Gangs are also frequently differentiated by the kinds of criminal behaviors in which they engage – i.e., violent gangs, income generating gangs, and delinquent gangs (Starbuck et al. 2001). Thus far, the majority of the research on gang structure has been largely descriptive and, therefore, limited from making topological comparisons.

SNA can advance this line of research by moving away from descriptive organizational characteristics to formal measures of group structures. This transition allows for testing organizational types, examining structural changes over time, as well as the ability to look at patterns of behavior, influence, and interaction. For example, network research on formal organizations suggests that informal relationships are often more significant in organizational behavior than formal hierarchical positions. Asking whether or not a gang has regular meetings overlooks the informal associations that may be at the heart of gang life. SNA has challenged conventional understandings of gang membership by showing how ties among individuals extend beyond the in-group and has also revealed more intricate relations within the larger gang structure (McGloin 2005). Frequently gang members are not friends, do not know one other, or have animosity toward one another. From a networked perspective, one builds the organizational structure from the ground up by tracing lines of influence and interaction among members.

A network approach to gangs has the potential to illuminate structural variation, model organizational changes over time, and examine organizational threat or stability. Figure 1, for example, presents structures representing actual lines of interaction among members, as opposed to a theoretical structure that may or may not fit the actual structure of the group. Formal analysis of networks sheds light on current typologies and develops new understandings of gang structures. One potential avenue of inquiry would compare the patterns of interaction within specified groups to group structures as reported by law enforcement or gang members. In many non-gang settings, often the informal networks of friendship have a stronger influence on behavior (see Haynie 2001). Another avenue of inquiry would compare structures at the group level in order to examine if particular network forms are more or less conducive to certain behaviors such as violence or drug dealing.

Structural Position

Not all gang members are alike. For decades, gang research has made important distinctions between the levels at which members participate in gang life and gang culture. Terms such as wannabes, hanger-ons, and associates typically refer to those individuals only causally involved in a gang, whereas terms such as hard core, down, or lifer are reserved for those more committed to gang life (Klein and Maxson 2006). Scholars often make the distinction between core and periphery gang members where the former refers to those who are active in the gang and the latter refers to members not central to the gang structure. The basic presupposition is that those who are more central to the gang structure are participating more fully in gang activities and those who are on the outskirts participate less.

Scholars also recognize the naıvete´ of such a core-periphery distinction. Gang participation is more amorphous than most typologies allow. Although popular media often depict gangs as secret societies with blood rituals and initiations, the reality is that gang membership is fluid (Fleisher 1999). Furthermore, membership is often unofficial; it is just as likely that membership is based on familial relations than a formal initiation. Some fully indoctrinated members may actually exert very little influence, while others who are not formal members may exert tremendous influence. Small cliques form within the group, which can at times divide the group into subdivisions, each with its own level of participation (Fleisher 1999; McGloin 2005; Papachristos 2006).

SNA can move research on gang participation forward by considering how positions within networks may or may not relate to levels of participation or vice versa. By empirically returning to basic gang networks (such as those in Fig. 1), analysts can use various network measures to find structural similarities or differences within and across groups. For example, one promising idea might be to analyze a sample of gang structures and test for structural equivalence in order to identify unique positions or roles in gangs.

Another potential line of inquiry might locate sources of influence within gang structures – i.e., locating individuals, such as brokers or gatekeepers, who might be significant not because of formal titles or positions but because of their influence on member behavior.

Network Action Of Street Gangs

Like other types of social groups, gangs can pursue collaborative goals, form alliances, and engage in collective action. Perhaps one of the most important areas of research on SNA and gangs investigates how gang network structures affect collective and individual action.

Gang Landscapes

SNA has the capacity to survey gang landscapes: the general patterns of relationships among a population or system of gangs (Kennedy et al. 1997). Social mapping of the collective relation- ships within a gang or across gangs offers insight into the organizational and territorial niches in which gangs exist. A gang landscape can map the alliances and rivalries between groups and individuals across a geographic space. Gang landscapes have the potential to situate specific gang activities and exchanges (such as violence and drug dealing) in the context of a total networked system. In other words a structural analysis illuminates gang actions and behaviors. For example, Descormiers and Morselli (2011) analyze how gang-level attributes (such as gang size, age of members, and ethnicity) and ecological factors (such as gang turf and underground economies) predict maps of gang alliances and conflicts in Montreal. In a slightly different approach, Papachristos (2009) maps the networks of violent exchanges between Chicago gangs over time and finds that prior relationships and the position of a gang in conflict networks are strong predictors of retaliation. This latter example demonstrates how patterns of the gang landscape provide insight into a social process of retaliation.

Group Processes

Gangs’ group-level actions include protection, socializing members, and supplying resources. These behaviors imply a number of social processes that are negotiated within the gang. Prior research has revealed the potential mechanisms within gangs that contribute to their crime and delinquency – e.g., loyalty, status, and protection (e.g., Short and Strodtbeck 1963). Protection is of particular importance because survey research has consistently found that protection is one of the most commonly cited reasons for joining youth gangs (Klein and Maxson 2006). In the quest for mutual protection, gangs face a basic collective action problem: they must motivate members to actually come to each other’s mutual aid in the face of a threat.

Network structures can facilitate or impede acts of mutual protection. In particular, the idea of cohesion, often measured as the density of ties within a network (Wasserman and Faust 1994), offers a fruitful direction for empirical analysis. A second approach to examining protection is by calculating the network density of gangs and correlating this with acts of violence – especially retaliation. For example, Papachristos (2009) found that gangs are more likely to reciprocate an act of violence when their actions are visible to other gangs. In other words, the collective processes involved in retaliation are more likely to occur when retaliation becomes a signal to other groups that a gang is capable of vengeance and protection. In addition to reinforcing the esprit de corps of the group, Papachristos (2009) finds such acts of retaliation can actually flame the spread of violence and create enduring networks of gang conflict that persist over time.

Research on gangs’ group processes and the ensuing consequences has been virtually untouched. The launch pad for such inquiry should focus on how specific hypothesized processes might manifest themselves structurally or on how structures affect the hypothesized processes. Just as understanding the sociodemographic characteristics of neighborhoods allow one to understand how social processes ecologically unfold, understanding the networks of street gangs better unpacks the social context in which group processes unfold.

Group Influence On Individual Action

One of the fundamental questions in gang research is the extent to which gangs (as groups) actually facilitate individuals’ delinquent or criminal behavior. This is in contrast to the selection effect perspective, which assumes likeminded and previously delinquent individuals come together to form a group (Bendixen et al. 2006; Thornberry et al. 2003). Mounting evidence from longitudinal studies supports a facilitation effect: individual delinquency is amplified in the gang context even when controlling for factors such as individual self-control, prior delinquency, and sociodemographic characteristics (Krohn et al. 2011; Thornberry et al. 2003). Individual delinquency, even among those with higher baseline delinquency, increases during periods of gang membership. However, what is still unclear is exactly how the gang facilitates crime and delinquency for the individual.

A growing body of network research shows that the structure of adolescent friendship networks is associated with self-reported delinquency, which can range from statutory crimes like underage drinking to more serious crimes like theft (Haynie 2001, 2002; McGloin 2009). In particular, this research finds considerable evidence for peer influence on delinquency: one’s own delinquency is related to the attitudes, behaviors, and delinquency of one’s peers. At the same time, only a handful of studies look at cooffending networks involved in serious crimes. Given the observed facilitation effect of gangs and the simple fact that gang associations appear more group-based than friendship networks, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the network effect of gangs on individual action should be larger than effects of friendship networks or co-offending networks. Furthermore, certain network configurations are more apt than others to facilitate imitation of behavior, to provide opportunities for deviance, and to exert stronger influence on its members. As such, we hypothesize that (a) the gang context amplifies group-level processes that foster delinquency and (b) gangs exhibit additional processes not found in delinquent peer groups.

Two recent studies by Papachristos and colleagues provide evidence for the group facilitation effect of gangs. In a study of gang members and their associates in Boston’s Cape Verdean community, Papachristos et al. (2012a) examine a social network of more than 700 individuals, approximately 30 % of whom are gang members. Their study finds that individuals in the network are more likely to be gunshot victims when (a) they are gang members, (b) their immediate social network is saturated with gang members, and (c) their immediate social networks contain other gunshot victims. In other words, network exposure to gang members and gunshot victims increases one’s own risk of being a victim. The second study surveys 150 active gun offenders in Chicago. Papachristos et al. (2012b) find that the network structure of individuals affects both their perceptions of the law and their subsequent law-violating behavior. In particular, individuals are more cynical of the law and subsequently more likely to engage in deviant behavior when their social networks are saturated with gang members. These two studies offer only a small glimpse into the ways network structure might influence individual actions and/or individual-level consequences. Future research should consider a wider range of group types (such as comparing gang members vs. non-gang members or members of other types of delinquent groups), different types of group processes (imitation, peer influence, and homophily), as well as various types of individual-level outcomes (beliefs, decisions, and behaviors).

Violence Prevention

From a social problem perspective, one of the most critical gang activities requiring attention is the incredibly high rate of lethal and nonlethal violence. A small but growing body of research has taken gang landscape mapping quite seriously as both a means of gang violence prevention and a research area. As part of a crime reduction initiative, Kennedy et al. (1997) mapped out gang rivalries and alliances in Boston. Violence intervention and prevention efforts relied on these network maps to direct attention toward gangs that were actively involved in shootings and target resources scarce to those gangs. This targeted group-based intervention strategy (of which gang network mapping was a key part) produced significant reductions in youth homicide and nonfatal shootings (Braga et al. 2001). Similar approaches evaluate the efficacy of group-based and outreach worker strategies in other US cities (Skogan et al. 2009; Tita et al. 2003).

Network Locations Of Street Gangs

Gangs are decidedly local phenomena with strong connections to the character and culture of urban neighborhoods. In fact, part of sociology’s continued fascination with gangs stems from their relationship to neighborhood social organization. Gangs are seen as de facto social institutions or collectivities that meet the basic needs of community and youth in otherwise disadvantaged communities. More than that, however, the neighborhood becomes a defining element of gang identity and group membership (Garot 2007; Grannis 2009). This association is so strong that many gang names incorporate their neighborhood of origins: the 35th Street Kings, Columbia Point Dogs, Westville Saints, and so on. Indeed, often the simple question “Where you from?” is a shorthand way for identifying gang members (Garot 2007). In a way, the gang itself becomes a reflection of many of the conflicts, cultures, and idiosyncrasies of the larger neighborhood.

Prior research has shown that space matters in shaping gang behaviors in at least two ways. First, and foremost, gang violence is commonly associated with the defense of gang turf or territory. Given the aforementioned attachment of gangs to urban space, threats to turf are considered threats to home, members’ safety, and the identity of the group. Violence stemming from the protection of turf becomes as much a symbolic measure signaling the solidarity and reputation of the gang and community as well as an instrumental gesture in protecting a piece of land over which a gang claims ownership. Secondly and perhaps related to such matters, previous research also suggests that gang violence is spatially contagious; gang violence in a given neighborhood affects levels of violence in adjacent neighborhoods. In a sense, the group and dynamic nature of gang violence spills over into adjacent communities. Though such spatial effects are associated with crime and violence more generally, a recent study of gangs in Los Angeles suggests that the spatial effects of gang violence extend beyond immediately adjacent geographic areas to affect more geographically distant neighborhoods (Tita and Radil 2011; Tita et al. 2003).

To date, with few exceptions, such spatial analyses of gangs rely mainly on regression models of aggregate crime measures – i.e., the extent to which crime rates in a focal neighborhood are associated with rates in surrounding communities. Yet, crime rates themselves do not move across gang turf or other geopolitical boundaries: gangs and gang members do. Nearly all empirical studies on the spatial nature of crime theoretically acknowledge that the social networks of criminal activity – such as drug dealing, prostitution, and gangs – drive the observed contagion of crime across neighborhood boundaries (e.g., Cohen and Tita 1999; Morenoff et al. 2001). Yet only a handful of studies actually incorporate social networks and geographic space into the same analysis, and even fewer studies have applied both to the study of gangs.

The inherent networked nature of gangs and their strong links to urban space propose an excellent area of study for understanding the convergence of social and geographic space. This line of inquiry would be relevant not only to gang research but also to social science more broadly. In fact a recent issue of Social Networks (Adams et al. 2012) was dedicated entirely to the convergence between spatial and network thinking. Statistical models of geographic and network autocorrelation share many similarities and, in their most basic principles, have a similar functional form. The gang, both theoretically and empirically, affords an important instance in which to understand the convergence of both geographic and social space. For example, combining social networks of gang relationships with geographic models of diffusion could shed light on whether the clustering of gang violence in particular neighborhoods is related to ecological conditions, group processes (such as reciprocity), or some combination therein. Likewise, analyses such as these might advance our understanding of whether institutional memory captured in social networks might trump geographic barriers. Alternatively, spatial network research could also provide valuable insight into the ways that group processes and geography may impede or promote behavior – the relevance of such findings extends well beyond the world of the street gang.

Concluding Remarks

To review, SNA affords many unique opportunities to consider the group nature of contemporary street gangs. By considering gangs as networks of individuals or by mapping systems of gangs, researchers can more accurately measure structures and processes that make the gang a unique sociological entity. This research paper has outlined some promising avenues for inquiry and, no doubt, many more exist. In advancing this network agenda for gang research, researchers should keep two things in mind. First, at the core of gang research is the inherent “groupness” of the gang. The application of SNA to gang research should proceed in a way that exploits new methodologies and data to understand this aspect of the gang. Second, the potential influence between SNA and gang research is bidirectional. This means that the application of SNA to gangs should not simply be a “cut-and-paste” of existing methodologies and ideas. Rather, the diligent application of SNA to gang research should provide insight into a range of small group behavior relevant to social science more generally.

Though enthusiastic about the direction of SNA and gang research, this research paper recognizes that the methodology is not without challenges or limitations, two of which are mentioned here. First and foremost, boundary specification issues haunt all SNA research (Laumann et al. 1989) and pose even greater limitations for theoretical and empirical considerations of gangs. Boundary specification refers to the problem in SNA of identifying where the network begins and where it ends. Boundary specification can be driven by data considerations (who is in a dataset) or by theoretical considerations (who is part of the group). As discussed above, SNA research on gangs has already demonstrated that boundaries of gangs – defined by gang membership – are rather amorphous (Fleisher 1999; McGloin 2005). This suggests that finding the “true” group may prove elusive. More precisely, the shape of the network will be contingent upon where analysts draw the boundary of the group – whether, for instance, to include only “gang members” or to also include their associates. Figure 1, for instance, stopped at 2 of separation from known gang members (i.e., those individuals who were friends of friends of known gang members). In short, SNA provides a new way to discuss group membership and structure, but ultimately boundary specification becomes immensely important for theory and empirical research.

Second, future research should explore the limits of existing data as well as consider how to improve future data collection efforts. SNA requires relational data: a data source that contains some reference to the relationship among units. In some instances, this means revisiting old data sources with a new theoretical lens. For example, the study of co-offending networks (Schaefer 2012) and the study of gang homicide networks (Papachristos 2009) relied on official police data common in criminological research. But it required these authors to understand a relational aspect of the data not previously considered: how events link individuals and groups. The network literature refers to this as two-mode data (see Wasserman and Faust 1994). Similarly, ethnographic data often provides extremely rich information on the social relationships of its subjects. Fleisher (1999), for example, coded his field notes for specific instances of social ties to help uncover the patterns of the group – a time-tested anthropological technique for understanding group membership. Papachristos (2006) has even gone back and coded published ethnographies to a similar end. Moving forward, gang researchers should include network-related questions in future survey collection efforts. Indeed, much of the growth of SNA in criminology can be attributed to the network focus of a handful of surveys of school youth. Subsequent surveys of gang members or law enforcement could advance this area of research considerably by adding even a single network question to their survey instruments.

Bibliography:

- Adams J, Faust K, Lovasi GS (eds) (2012) Capturing context: integrating spatial and social network analysis [Special issue]. Social Networks 34(1):1–158

- Bendixen M, Endresen IM, Olweus D (2006) Joining and leaving gangs: selection and facilitation effects on selfreported antisocial behavior in early adolescence. Eur J Criminol 3(1):85–114

- Bouchard M, Spindler A (2010) Groups, gangs, and delinquency: does organization matter? J Crim Justice 38(5):921–933

- Braga AA, Kennedy DM, Piehl EJ, Morrison A (2001) Problem-oriented policing: an evaluation of Boston’s operation ceasefire. J Res Crime Delinq 38(3):195–225

- Cohen J, Tita G (1999) Diffusion in homicide: exploring a general method for detecting spatial diffusion. J Quant Criminol 15(4):451–493

- Descormiers K, Morselli C (2011) Alliances, conflicts, and contradictions in Montreal’s street gang landscape. Int Crim Justice Rev 21(3):297–314

- Emirbayer M (1997) Manifesto for a relational sociology. Am J Sociol 103(2):281–317

- Fleisher M (1999) Dead end kids: gang girls and the boys they know. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison

- Garot R (2007) ‘Where you from!’: gang identity as performance. J Contemp Ethnogr 36(1):50–84

- Grannis R (2009) From the ground up: translating geography into community through neighbor networks. Princeton University Press, Princeton

- Haynie D (2001) Delinquent peers revisited: does network structure matter? Am J Sociol 106(4):1013–1057

- Haynie D (2002) Friendship networks and delinquency: the relative nature of peer delinquency. J Quant Criminol 18(2):99–134

- Kennedy DM, Braga A, Piehl A (1997) The (un)known universe: mapping gangs and gang violence in Boston. In: Weisburd D, McEwen T (eds) Crime mapping and crime prevention. Criminal Justice Press, New York, pp 219–262

- Klein MW, Maxson CL (2006) Street gang patterns and policies. Oxford University Press, New York

- Krohn M, Ward J, Thornberry TP, Lizotte A, Chu R (2011) The cascading effects of adolescent gang involvement across the life course. Criminology 49(4):991–1028

- Laumann EO, Marsden PV, Prensky D (1989) The boundary specification problem. In: Freeman L, White D, Romney A (eds) Research methods in social network analysis. George Mason University Press, Fairfax, pp 61–87

- McGloin JM (2005) Policy and intervention considerations of network analysis of street gangs. Criminol Pub Policy 4(3):607–635

- McGloin JM (2009) Delinquency balance: revisiting peer influence. Criminology 47(2):437–477

- McGloin JM, Kirk D (2010) Social network analysis. In: Piquero A, Weisburd D (eds) Handbook of quantitative criminology. Springer, New York, pp 209–224

- Morenoff JD, Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW (2001) Neighborhood inequality, collective efficacy, and the spatial dynamics of homicide. Criminology 39(3):517–560

- Papachristos AV (2006) Social network analysis and gang research: theory and method. In: Short JF, Hughes LA (eds) Studying youth gangs. AltaMira Press, Lanham, pp 99–116

- Papachristos AV (2009) Murder by structure: dominance relations and the social structure of gang homicide. Am J Sociol 115(1):74–128

- Papachristos AV (2011) The coming of a networked criminology? Using social network analysis in the study of crime and deviance. In: MacDonald J (ed) Measuring crime and criminality: advances in criminological theory, vol 17. Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick, pp 101–140

- Papachristos AV, Braga AA, Hureau DM (2012a) Social networks and the risk of gunshot injury. J Urban Health 89(6):992–1003

- Papachristos AV, Meares TL, Fagan J (2012b) Why do criminals obey the law? The influence of legitimacy and social networks on active gun offenders. J Crim Law Criminol 102(2):101–144

- Pyrooz DC, Fox AM, Katz CM, Decker SH (2012) Gang organization, offending, and victimization: a cross-national analysis. In: Esbensen FA, Maxson CL (eds) Youth gangs in international perspective: tales from the Eurogang program of research. Springer, New York, pp 85–105

- Sanchez-Jankowski MS (1991) Islands in the street: gangs and American Urban Society. University of California Press, Berkley

- Schaefer DR (2012) Youth co-offending networks: an investigation of social and spatial effects. Social Networks 34(1):141–149

- Short JF, Strodtbeck FL (1963) The responses of gang leaders to status threats: an observation on group process and delinquent behavior. Am J Sociol 68(5):571–579

- Skogan WG, Hartnett SM, Bump N, Dubois J, Hollon R, Morris D (2009) Evaluation of ceasefire-Chicago. http://www.ipr.northwestern.edu/publications/ceasefire_papers/mainreport.pdf. Retrieved 8 Mar 2012

- Starbuck D, Howell J, Linquist D (2001) Hybrid and other modern gangs. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Washington, DC

- Thornberry TP, Lizotte AJ, Krohn MD, Smith CA, Porter PK (2003) Causes and consequences of delinquency: findings from the rochester youth development study. In: Thornberry TP, Krohn MD (eds) Taking stock of delinquency: an overview of findings from contemporary longitudinal studies. Kluwer/Plenum, New York, pp 11–46

- Tita G, Radil S (2011) Spatializing the social networks of gangs to explore patterns of violence. J Quant Criminol 27(4):521–545

- Tita G, Jack Riley K, Ridgeway G, Grammich C, Abrahamse AF, Greenwood PW (2003) Reducing gun violence: results from an intervention in East Los Angeles. RAND Corporation, Santa Monica

- Venkatesh S, Levitt SD (2000) An economic analysis of a drug-selling gang’s finances. Q J Econ 115(3):755–789

- Wasserman S, Faust K (1994) Social network analysis: methods and applications. Cambridge University Press, New York

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.