This sample Structured Sentencing Outside the US Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

How much discretion should judges have at sentencing? If they have too much, disparity of outcome will be the inevitable consequence. On the other hand, removing their discretion entirely will result in injustice. The solution to this problem lies in the concept of sentencing guidelines which in theory at least provide direction to courts but without unduly restricting their discretion. The US-style grid-based guidelines are only one form of sentencing guidelines; other models are possible. This research paper reviews the experience in jurisdictions other than the USA. Several countries have attempted to structure judicial discretion at sentencing in different ways. These other forms of guidance represent alternative approaches to promoting consistency at sentencing. After noting some developments in some other countries, this research paper focuses on the experience in England and Wales which is the only common law jurisdiction outside the United States to have developed and adopted a comprehensive sentencing guidelines scheme.

Introduction

When most judges or other criminal justice professionals think about sentencing guidelines, the systems found across the United States come readily to mind. Sentencing guidelines have been evolving in that country for over 30 years now, at both the state and federal levels. Most states have a formal sentencing guidelines scheme to assist judges at sentencing. The best known guidelines model involves a two-dimensional sentencing grid – much like a mileage chart which shows the distance between two cities. Under a sentencing grid, the two dimensions are crime seriousness and criminal history. In order to determine the sentence that should be imposed, a court selects the appropriate level of seriousness and the appropriate criminal history category. Where the crime seriousness row and the criminal history column intersect, there is a grid cell containing a relatively narrow range of sentence length. Sentencing grids of this kind are found in a number of states including Minnesota (e.g., Minnesota Sentencing Guidelines Commission 2010a; Frase 2005, 2009).

If the guidelines are presumptively binding (some states use advisory guidelines, and the US federal guidelines are now considered advisory following several judgments from the US Supreme Court), the court must impose a sentence within the range found in the guidelines grid. A court wishing to impose a more or less severe sanction than that which is prescribed by the guidelines must first find “substantial and compelling” reasons to justify what then becomes a “departure” sentence, namely, one outside the official guideline ranges. Departure rates vary across the US systems. Statistics from Minnesota reveal that in 2009, 25 % of all felony offenders received a sentence different from that prescribed by the guidelines, while a further 14 % of all sentences of custody were outside the guidelines sentence length limits (Minnesota Sentencing Guidelines Commission 2010b, p. 26). The total departure rate for 2009 was therefore 38 %. Departure rates in other states are lower. In Pennsylvania, only 10 % of sentences imposed in 2008 fell outside the guidelines; over the period 1985–2008, the departure rate averaged 11 % (Pennsylvania Commission on Sentencing 2009, p. 46). In Oregon, less than one-fifth of sentences were outside the guidelines (Oregon Criminal Sentencing Commission 2003, p. 13).

Structuring judicial discretion at sentencing is one of the most significant challenges for a legislature. If they prescribe specific sentences – such as mandatory terms of custody – courts are prevented from doing justice by reflecting the individual circumstances of specific offenders. For example, legislating a mandatory sentence of imprisonment for all convictions of robbery means that offenders of different levels of culpability will receive the same sentence – a clear injustice. On the other hand, if legislatures leave the courts to regulate themselves at sentencing, outcomes may be too variable, leading to sentencing disparity. In short, it is a fine balance between offering too much and too little structure.

Sentencing Reform In Other Jurisdictions: Guidance By Words Alone

Sentencing guidelines do not have to be numerical in nature, providing a specific range of sentence for each crime. A number of Scandinavian countries have developed what may be termed “guidance by words” (see also Ashworth (2009) for discussion of techniques to reduce disparity through increased guidance). This approach to structured sentencing involves the legislature placing relatively detailed guidance in a sentencing law. For example, the Swedish Penal Code identifies proportionality as the primary rationale for sentencing and requires courts to assess the seriousness of the crime in order to determine sentence. A number of mitigating and aggravating factors are also specified in the Swedish sentencing law in order to guide judges in the determination of sentence. Finally, the law also contains guidance for courts with respect to the choices they should make between different sentencing options (for further information, see von Hirsch and Jareborg 2009). The advantage of the “guidance by words” approach is that it leaves courts with considerable flexibility to determine an appropriate and proportionate sentence. On the other hand, this may result in much greater disparity than would be the case in a jurisdiction such as Minnesota where judges have to follow detailed and prescriptive sentencing guidelines.

Sentencing Structures: Commissions And Councils

How would a country go about creating a sentencing guidelines scheme? The first step in any move towards structuring judicial discretion involves the creation of an independent authority to developing and issuing sentencing guidelines. All US guidelines schemes emerge from a sentencing commission, such as the Minnesota Sentencing Guidelines Commission or the US Sentencing Commission at the federal level. In other countries, these bodies are usually called Sentencing Councils, and there is significant variation in their structures and functions. The Sentencing Council of England and Wales is headed by the Lord Chief Justice and is tasked with devising and disseminating guidelines as well as a range of other functions (see Roberts 2011, 2012). On the other hand, sentencing councils in Australia such as the Sentencing Advisory Council in New South Wales are, as the name implies, advisory in nature. These councils do not issue sentencing guidelines per se but rather provide advice and conduct research upon a wide range of sentencing matters.

All sentencing councils are involved in public legal education of one kind or another. This may mean publishing reports to help the public understand the sentencing process better, or it may mean releasing comprehensive sentencing statistics. For example, some guidelines authorities publish periodic Sentencing Bulletins which summarize sentencing trends for specific offenses (see http://sentencingcouncil.vic.gov. au/page/about-us/council). The public typically rely on news media accounts of sentencing decisions, and these generally focus on unusual or exceptionally lenient sentences – those which are newsworthy in some respect. It is important therefore for a guidelines authority to dispel public misperceptions of sentencing.

Progress towards developing sentencing guidelines around the world has been fitful and slow. The Law Commission of New Zealand developed a comprehensive and principled set of guidelines, but the legislature in that jurisdiction has yet to proclaim the necessary legislation to permit implementation (see Young and Browning 2008). The New Zealand scheme involved a comprehensive guideline for each offense; the guideline contained categories of crime seriousness, each with an associated range of sentence. A sentencing court would match the case appearing for sentencing to the guideline category using information in the guideline. The system was more flexible than the US-based schemes. The New Zealand proposed guidelines also included “generic” advice – guidelines which apply to more than a single offense. For example, the guidelines provide guidance on considering the impact of the crime upon the victim and also the way in which courts should approach the sentencing of multiple crimes on the same occasion.

Other jurisdictions – including Scotland, Western Australia, Northern Ireland, and Israel – have explored the use of guidelines for sentencers but so far have not actually adopted a formal scheme. The Sentencing Commission for Scotland recommended creation of an Advisory Panel on Sentencing to assist the introduction of sentencing guidelines, but this has yet to become operational (see Hutton and Tata 2010). Following recommendations from a Sentencing Working Group (2010), Northern Ireland held a consultation on the possible options for a form of sentencing guidelines (Criminal Policy Unit 2010).

In January 2012, the Israeli Parliament (Knesset) approved a sentencing law. This law adopted parts of a Bill which provide for “guidance by words” but without establishing the guidelines authority which would have been empowered to develop and issue guidelines scheme involving “starting point sentences” (see Gazal-Ayal and Kannai 2010). Under the new legislation, courts are required to devise their own proportionate sentence range for the case being sentenced and to provide reasons if they impose a sentence outside this range. South Korea has also launched a guidelines scheme (see Park 2009). Several jurisdictions (including New South Wales and the state of Victoria in Australia) have created advisory bodies which disseminate information about sentencing but which do not actually disseminate guidelines (see Abadee (2008) and more generally, Freiberg and Gelb 2008).

Countries Without Guidelines

Finally, some countries – Canada, South Africa, Ireland, and India, for example – have resisted all appeals for greater structure at sentencing (e.g., Terblanche 2003; Doob 2011; Roberts et al. 2011). Although scholars and practitioners in those countries have long advocated creation of some kind of guidelines scheme, legislatures in these countries have so far rejected calls to introduce sentencing guidelines. The consequence is that judges in these jurisdictions continue to impose sentence much as they have for decades, with the only guidance coming from the appellate courts. This approach to sentencing may be termed “judicial self-regulation” (see Ashworth 2009). The limitation of this approach is that higher courts hear only a small proportion of cases on appeal, which means that the opportunities for guidance are limited. When a court of appeal does hear a sentence appeal, it does not always give general guidance.

Guidelines Structures

If appropriately constructed, and not subject to political interference, sentencing guidelines remain the best hope for constraining prison populations and achieving principled sentencing (see Stemen and Rengifo (2011); von Hirsch et al. (2009)), but the question remains: what form of guidelines is appropriate for any given jurisdiction? The guidelines movement remains strong across the USA, but despite its high profile, the model employed in states such as Minnesota has not proven a popular penal export. Canada was the first country to reject this approach to structured sentencing.

In 1984, the Canadian government created a term-limited Sentencing Commission which visited several American states (including Minnesota and Pennsylvania) and concluded that two-dimensional grids held no promise for sentencing in Canada (see Canadian Sentencing Commission 1987). Canada’s flirtation with guidelines ended in the 1990s when its Parliament approved a modest sentencing reform package and declined to create a permanent sentencing commission or to create guidelines of an even advisory nature (see Roberts and Cole 1999; Doob 2011). A generation later the Sentencing Commission Working Group in England and Wales visited the home of numerical guidelines and drew the same conclusion (Sentencing Commission Working Group 2008). Western Australia considered adopting a two-dimensional sentencing grid in 1999 but also ultimately abandoned the idea.

The proliferation of two-dimensional sentencing grids across the USA since the 1970s may paradoxically have undermined the appeal of all presumptively binding guidelines. Sentencing guidelines of any kind are often regarded by judges as harbingers of grids and as being antithetical to sentencing as a “human process” (see Hogarth 1971). Calls for the introduction of any kind of sentencing guidelines system are perceived as an attempt to move towards the ultimate goal of a grid. Indeed, opposition in Canada (and England and Wales) to sentencing guideline schemes of all stripes was fueled by predictions that any move towards structuring judicial discretion would culminate in the imposition of a rigid two-dimensional grid. In England and Wales, despite considerable judicial and professional resistance to the concept of guidance derived from a source other than the Court of Appeal, guidelines have slowly emerged over the past decade. Definitive guidelines now exist for most high-frequency offenses.

Sentencing Guidelines In England And Wales

Distinguishing Guideline Schemes In The USA And England

The English guidelines offer a different but equally viable model to follow, and there are lessons for other jurisdictions seeking to impose greater structure at sentencing without adopting a US-style two-dimensional grid. Guidelines have been developing slowly in England and Wales since creation of the Sentencing Advisory Panel in 1998. In addition, the Court of Appeal has been issuing guideline judgments periodically over the years. Courts in England and Wales have therefore a tradition of guidance on which to draw. However, with the creation of the Sentencing Council in 2010 (see Roberts 2011), the guidelines entered a new area, and the new Council began issuing guidelines more frequently and in a new format.

How do the English sentencing guidelines differ from the US-based schemes? The principal difference is that guidelines in England and Wales promote consistency by requiring sentencers to proceed through a series of steps. This represents a different approach to promoting consistency in sentencing. The effectiveness of the English approach has not been evaluated, as the Council responsible for issuing the guidelines has yet to publish the data which will shed light on any changes in consistency of sentencing outcomes. The second principal difference between the English and the US guidelines is that Sentencing Commissions across the USA devise and S issue a complete package of guidelines encompassing all offenses – usually, as noted, within a single guidelines grid. The English Sentencing Council issues guidelines sequentially for each offense category (such as all assault offenses, or drugs crimes). This means that it takes longer for guidelines to be available for all offenses. (All English guidelines are available at http://sentencingcouncil.judiciary.gov.uk/).

Step-By-Step Sentencing Methodology

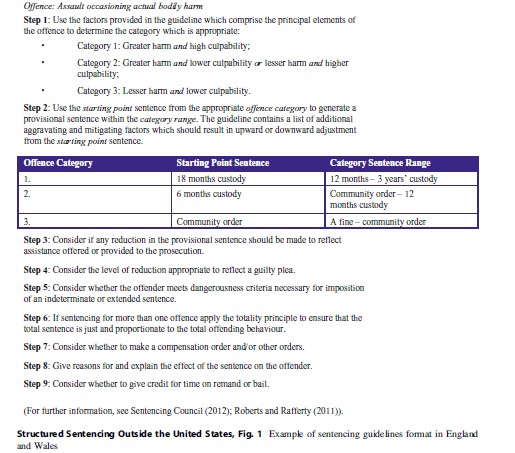

How do the English guidelines work? The English guidelines structure contains a series of nine steps, of which the first two are the most critical. (See Fig. 1 for a summary of the steps). The idea is that if all courts follow the same step-by-step procedure, sentencing decisions across courts should be more consistent.

For the purposes of illustration, let us examine the guideline for Assault occasioning actual bodily harm (see Sentencing Council of England and Wales 2011). As with many offenses for which a definitive guideline has been issued, ABH has been stratified into three categories of seriousness. The guideline provides a separate range of sentence and starting point sentence for each category. Step 1 of the guidelines methodology requires the sentencing court to match the case appearing for sentencing to one of the three categories of seriousness. The three categories have been created to reflect gradations in harm and culpability, with the most serious category (1) requiring greater harm and enhanced culpability. Category 2 is appropriate if either greater harm or higher culpability is present, while Category 3 involves lesser harm and a lower level of culpability.

Determining The Offense Category

Step 1 of the guideline identifies an exhaustive list of sentencing factors which should be used to determine which of the three categories of seriousness is most appropriate for the particular offender appearing for sentencing. These factors constitute what the guideline describes as the “principal factual elements” of the offense. Their importance is reflected in the fact that determination of the category range is the step which will have greatest influence on severity of sentence. For example, if the court chooses the lowest category, the most severe sentence it should impose is a community-based (noncustodial) sentence. In contrast, the next category up has a maximum sentence of 51 weeks imprisonment. Having determined the relevant category range, a court should use the corresponding starting point sentence to move towards a sentence which will then be shaped by the remaining steps in the guideline.

Step Two: Shaping The Provisional Sentence

Step 2 requires a court to “fine-tune” the sentence by considering circumstances which provide “the context of the offense and the offender.” The guidelines provide a non-exhaustive list of sentencing factors for courts to consider at this step of the methodology. The aggravating factors include committing the offense while on bail or license, while under the influence of drugs, or with abuse of trust. The guideline factors which reduce seriousness (and which result in less severe sentence) include an absence of prior convictions and the fact that the crime was an isolated incident. A diverse collection of factors is cited as relevant to personal mitigation, including remorse, the fact that the offender was a sole or primary carer and “good character and/or exemplary conduct.”

Other Steps Towards The Final Sentence

Leaving Step 2 leads a court to the remaining seven steps of the guidelines methodology, which may be briefly summarized. Step 3 directs courts to reduce sentence in cases where the offender has provided or offered to provide assistance to the prosecution or police. Step 4 involves the reduction for a guilty plea. Offenders who plead guilty receive a reduction of up to one-third off their custodial sentence, depending upon how early they enter their plea. The remaining steps to be followed relate to other sentencing provisions such as the consideration of any time that the offender spent in remand while awaiting trial. (This time is taken off any custodial sentence ultimately imposed). The guideline steps also require the court to give reasons for the sentence imposed and to explain the effect of the sentence for the benefit of the offender. Finally, courts give reasons for the sentence and, in particular, if they have imposed a sentence which falls outside the guidelines range.

Legal Status Of English Guidelines

As noted, in many US states, the sentencing guidelines are binding on courts: a judge may depart from the guideline range if he or she finds “substantial and compelling” reasons why the guideline sentence is inappropriate. The English guidelines are less restrictive, although they are formally binding on courts. When sentencing an offender in England and Wales, a sentencing court “must follow” any relevant sentencing guidelines – unless it would be contrary to the interests of justice to do so (see discussion in Ashworth 2010). However, courts may impose a sentence within a wide range and still remain compliant with the guidelines. In this sense, although they are required to follow the guidelines, courts retain considerable freedom to sentence offenders: first, they have considerable discretion within the guidelines, and second, they may depart from the guidelines if they believe it is necessary in the interests of justice.

Conclusion

What have we learned about the experience with structuring sentencers’ discretion outside the United States? A number of lessons can be drawn. First, the Scandinavian model suggests that numerical guidelines are not necessarily the only model to follow. It is possible to offer guidance to courts without prescribing specific sentencing ranges in terms of numbers of months or years. Second, the English guidelines demonstrate that there is a middle ground lying between the relatively tight sentencing guidelines found across the United States and the looser systems of “guidance by words” found in countries like Sweden and Finland (see von Hirsch et al. 2009, Chapter 6). Along with the New Zealand proposals, the English guidelines offer a system which is numerical, prescriptive, and yet quite flexible in application. These two systems offer a plausible improvement upon the highly discretionary sentencing arrangements found in countries like Canada, South Africa, and India. Third, judicial acceptance of greater structure (and reduced discretion) is far more likely when the judiciary is heavily implicated in the development and evolution of the guidelines. The statutory bodies responsible for the guidelines in England and Wales have generally been dominated by the judiciary. The Canadian Sentencing Commission proposals failed, in part because judges perceived the guideline scheme to be a bureaucratic scheme created by academics.

Fourth, there may be an advantage to the gradual evolution of the guidelines. The English guidelines have been criticized for being slow to develop – with guidelines for specific offenses issued periodically over the years rather than in one step as was the case in the United States or the proposals advanced in New Zealand. There was no “big bang” to the English experience in the sense of a comprehensive guidelines package covering all offenses. In retrospect, this potential weakness of the guidelines may paradoxically have ensured their survival and development. They have evolved incrementally – from their modest origins in 1999 (see Ashworth and Wasik 2010) through to the much more comprehensive and detailed scheme of 2011. Judges who are traditionally resistant to any attempts to curb their discretion may be more likely to accept guidance when it comes in this format.

The ultimate question to pose, however, is the following: Are the guidelines proposed or implemented in other countries better or worse, more or less effective than those developed across the United States? Unfortunately the absence of truly comparative research makes it impossible to resolve the issue one way or another. In addition, the non-US-based guidelines such as those in England have yet to be evaluated. For example, we do not yet know how much the English guidelines have improved consistency in that country. At the very least, however, the experience in that country demonstrates that it is possible to introduce detailed and prescriptive sentencing guidelines even in a common law jurisdiction which, in the 1980s and 1990s, was committed to the traditional model of privileging judicial discretion (see Ashworth 2010).

Bibliography:

- Abadee A (2008) The New South Wales sentencing council. In: Freiberg A, Gelb K (eds) Penal populism, sentencing councils and sentencing policy. Willan, Cullompton

- Ashworth A (2009) Techniques for reducing sentence disparity. In: von Hirsch A, Ashworth A, Roberts JV (eds) Principled sentencing. Readings on theory and policy, 3rd edn. Hart Publishing, Oxford

- Ashworth A (2010) Sentencing and criminal justice, 5th edn. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

- Ashworth A, Wasik M (2010) Ten years of the sentencing advisory panel. In: Sentencing advisory panel annual report. Available at: www.sentencing.council.org

- Canadian Sentencing Commission (1987) Sentencing reform: a Canadian approach. Supply and Services Canada, Ottawa

- Criminal Policy Unit (2010) Consultation on a sentencing guidelines mechanism. Northern Ireland Department of Justice, Belfast

- Doob AN (2011) The unfinished work of the Canadian Sentencing Commission. Can J Criminol Crim Justice 55:279–298

- Frase R (2005) Sentencing guidelines in Minnesota, 1978–2003. In: Tonry M (ed) Crime and justice. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Frase R (2009) Sentencing policy under the Minnesota sentencing guidelines. In: von Hirsch A, Ashworth A, Roberts JV (eds) Principled sentencing. Readings on theory and policy, 3rd edn. Hart Publishing, Oxford

- Freiberg A, Gelb K (eds) (2008) Penal populism, sentencing councils and sentencing policy. Willan, Cullompton

- Gazal-Ayal O, Kannai R (2010) Determination of starting sentences in Israel – system and application. Fed Sentencing Report 22:232–242

- Hogarth J (1971) Sentencing as a human process. University of Toronto Press, Toronto

- Hutton N, Tata C (2010) A sentencing exception? Changing sentencing policy in Scotland. Fed Sentencing Report 22:272–278

- Minnesota Sentencing Guidelines Commission (2010a) Minnesota sentencing guidelines and commentary. Revised, Aug 2010. MSGC, St. Paul

- Minnesota Sentencing Guidelines Commission (2010b) Sentencing practices. Annual summary statistics for felony offenders sentenced in 2009. MSGC, St. Paul

- Oregon Criminal Sentencing Commission (2003) Sentencing practices, 2001. State of Oregon, Criminal Sentencing Commission, Salem

- Pennsylvania Commission on Sentencing (2009) Sentencing in Pennsylvania. Annual report 2008. Available at: http://pcs.la.psu.edu/

- Park H (2009) The basic features of the First Korean sentencing guidelines. Korean Ministry of Justice, Seoul

- Roberts JV (2011) Sentencing guidelines and judicial discretion: evolution of the duty of courts to comply in England and Wales. Br J Criminol 51:997–1013

- Roberts JV (2012) Structured sentencing: lessons from England and Wales for common law jurisdictions. Punishment and society. Int J Penol 14(3):267–288

- Roberts JV, Azmeh U, Tripathi K (2011) Structured sentencing in England and Wales: lessons for India? Natl Law School India Rev 23:27–46

- Roberts JV, Cole D (eds) (1999) Making sense of sentencing. University of Toronto Press, Toronto

- Roberts JV, Rafferty A (2011) Structured sentencing in England and Wales: exploring the new guideline format. Crim Law Rev 9:680–689

- Sentencing Commission Working Group (2008) Sentencing guidelines in England and Wales: an evolutionary approach. SCWG, London

- Sentencing Council of England and Wales (2011) Assault. Definitive guideline. Available at: http://sentencingcouncil.judiciary.gov.uk/

- Sentencing Working Group of Northern Ireland (2010) Monitoring and developing sentencing guidance in Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland Department of Justice, Belfast

- Stemen D, Rengifo A (2011) Policies of imprisonment: the impact of structured sentencing and determinate sentencing on state incarceration rates, 1978–2004. Justice Q 28:174–201

- Terblanche S (2003) Sentencing guidelines for South Africa: lessons from elsewhere. S Afr Law J 120:858–882

- von Hirsch A, Ashworth A, Roberts JV (eds) (2009) Principled sentencing. Readings on theory and policy, 3rd edn. Hart Publishing, Oxford

- von Hirsch A, Jareborg N (2009) The Swedish sentencing law. In: von Hirsch A, Ashworth A, Roberts JV (eds) Principled sentencing. Readings on theory and policy, 3rd edn. Hart Publishing, Oxford

- Young W, Browning C (2008) New Zealand’s sentencing council. Crim Law Rev, April 2008, pp 287–298

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.