This sample Youth Homicide in The US Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Overview

This research paper reviews youth homicide trends in the United States over a 23-year period and describes key factors affecting increases and decreases in homicides by youth. It also summarizes a study of youth homicide perpetration from 1984 to 2006 that examined trends and predictors for two groups of young perpetrators – 13–17-year-olds and 18–24-year-olds. This study modeled city-specific predictors of increases in homicides by these age groups for 91 of the largest US cities. Overall, findings indicate that rates of homicide for juvenile and young adults followed the same general pattern over the 23 years: with a sharp escalation in 1984–1993, a significant downturn from 1994 to 1999, and a subsequent increase in 2000–2006. Structural disadvantage in large US cities was strongly associated with the sharp rise in perpetration of homicide by juveniles and young adults during the national homicide “epidemic” in the mid-1980s to early 1990s, as well as the more recent increase from 2000 to 2006. Gang presence and activity and illegal drug market activity were also consistently associated with increases in homicide offending by both age groups for both periods. Density of alcohol retail outlets had a significant relationship with increases in youth homicide perpetration for both age groups as well. This research paper concludes with recommendations for prevention for city officials, local and federal legislators, stakeholders, providers, and advocacy groups.

Trends In Youth Homicide In The United States: 1984–2005

Since 1984, the United States has experienced two dominant trends in youth homicide: a dramatic increase in the mid-1980s and early 1990s, followed by a sharp decline for the rest of that decade. From the mid-1980s until the early 1990s, US homicide rates rose to their highest level since the beginning of modern crime statistics. This startling and unanticipated increase was characterized as an “epidemic” by leading homicide investigators like Cook and Laub (1998) and Messner and his colleagues (2005). It mostly involved males, was fairly widespread across the country, and predominantly involved firearms (Fox and Zawitz 2002; Messner et al. 2005). Leading homicide researchers like Blumstein and his colleagues (2000), Cook and Laub (1998), Ousey and Augustine (2001), Ousey and Lee (2002), and many others offered explanations for the epidemic. Theories included greater prevalence of drug trafficking and drug markets in cities, greater availability and carrying of firearms, increased gang activity, changes in labor market structures, diminished economic opportunities for people living in marginalized communities, and diminished social and monetary support for families in poverty.

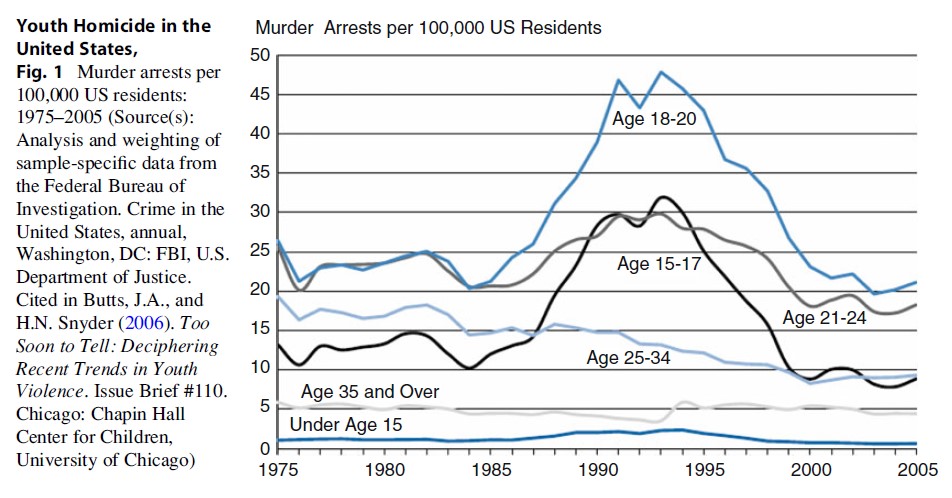

This historic spike in youth homicide culminated in 1993. Homicide rates then dropped dramatically, again unexpectedly. Explanations offered for the decline included reduced activity in illegal drug markets and lessening demand, improved economic conditions, greater access to housing and employment in urban areas, changes in alcohol consumption, and increased emphasis on law enforcement and imprisonment (e.g., Blumstein 1995; Blumstein and Wallman 2006; Blumstein et al. 2000; Ousey and Lee 2002; Moore and Tonry 1998). The decline lasted until the early 2000s, when reports from some US cities indicated a resurgence of urban-based violence by juveniles and young adults. National statistics also reflected an upsurge in violence and use of firearms among these groups. Homicide rates for young black males began to trend up in 2000 (Snyder and Sickmund 2006). Overall arrests of 15–24-year-olds for murder, robbery, and weapons offenses increased in 2004–2005 – for the first time in a decade (Butts and Snyder 2006). This unanticipated shift encouraged a renewed emphasis on identifying predictors of change (Fig. 1).

Factors Affecting Homicide Trends In The USA

The Relationship Between Cities And Homicide

Homicide trends vary greatly across types of homicide, as well as by age, race, circumstance context, relationship, and gender (e.g., Flewelling and Williams 1999; Williams and Flewelling 1988; Blumstein 1995; Parker and Rebhun 1995). Rates must be disaggregated by key characteristics in order to identify patterns and predictors, since aggregated rates often mask counter trends and circumstances influencing homicide patterns for different groups (e.g., Browne and Williams 1993; Browne et al. 1999). To understand youth homicide in the USA, it is critical to assess dynamics within cities, due to (a) the high proportion of US homicides that occur in urban areas and (b) the predominance of young, mostly male, perpetrators and victims in city-based homicide events.

Homicide trends vary across cities as well. For example, although the unprecedented increase in youth-perpetrated homicides from the mid-1980s to the early1990s was called a “national” epidemic, many US cities did not experience an increase in youth homicide during that period, and those that did demonstrated differing patterns in the epidemic’s beginning, duration, and decline. Using Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) data, Messner and his colleagues (2005) analyzed overall homicides rates for large US cities for the years 1979–2001 and found that just over half of the cities in the sample conformed to the national trend over the period. Large cities were most likely to experience an epidemic-like cycle; densely populated cities and cities with more severe levels of socioeconomic deprivation tended to have earlier entrance into and exit from the spike in youth homicide rates.

Similarly, McDowall and Loftin (2009) analyzed the extent to which trends in city-based crime rates corresponded to national crime trends over time using panel data from 139 large cities with populations over 100,000 for at least 30 years of a 45-year period (1960–2005), based on UCR offenses and population rates. In that 45-year period, national conditions must have exerted an effect at the city level during years of stability, rapid increase, and rapid decline to influence city crime rates. Results indicated that in an average year, nearly two-thirds of cities and their residents were subject to the national crime trend for that period. As with Messner et al.’s findings, larger cities were most likely to follow the national pattern, although smaller jurisdictions were also affected by nationwide conditions. Much of the variation in city crime rates remained dependent on local conditions within cities, however. National trends accounted for only about one-fifth of variation in local rates when between-city differences were removed.

City Characteristics Associated With Homicide

A variety of characteristics have been associated with homicide rates at the city level. In their classic study of between-city differences, Land and colleagues (Land et al. 1990) identified a set of key covariates that included resource deprivation (and/or affluence), e.g., families living below the poverty line, median family income, income inequality, and percent unemployed; family structure, e.g., percent divorced males and percent of children not living with both parents; population structure, including size and density and percent of the youth population; and geographical region in the USA. After the youth homicide epidemic of the late 1980s and early 1990s, other explanatory variables were added, including increases in illicit drug activity (particularly the trafficking of crack cocaine) and drug markets, a rise in US incarceration rates after 1980, and changes in law enforcement practices (Ousey and Lee 2002).

McCall and her colleagues (2008) extended earlier research by studying the extent to which within-city (rather than between-city) changes in structural covariates were associated with changes in the homicides rate for 83 of the largest US cities (populations over 100,000) from 1970 to 2000 and added shifts in the economy. Using a pooled cross-sectional time series model to examine the influence of within-city changes in covariates on changes in homicide rates over time, this study found that changes in resource deprivation, changes in the relative size of the youth population, and increases in drug sales arrest rates were significantly related to changes in homicide rates over four time points: 1970, 1980, 1990, and 2000.

Baumer (2008) also attempted to extend prior work on covariates by developing a more defined portrait of the determinants of crime trends for 1980–2004. He incorporated prior traditional factors and added immigration, wages, alcohol consumption, and youthful cohort variables for a sample of 114 US cities with populations of 100,000 or more (in 1980). Based on econometric panel modeling techniques, Baumer reported that unemployment rates were associated with increases in gun homicide rates overall; wages were negatively associated with non-gun homicides (pp. 159). Drug market measures yielded the most consistent significant effects in the study; these effects were strongest for youth homicide arrests. Baumer estimated that between 20 % and 40 % of the increases in the rates of overall homicide, gun homicide, and youth perpetrated homicide from 1984 to 2004 were attributable to drug market activity and drug involvement. Conversely, a drop in unemployment during the 1990s coupled with a rise in wages during that period explained as much as 30 % of the decline in youth and non-gun homicides.

Structural Disadvantage In Cities

The impact of economic and social disadvantage on lethal violence in cities has been documented across empirical studies of youth and adult homicide (Blumstein and Wallman 2006; Ousey and Augustine 2001; McCall et al 2008; Williams and Flewelling 1988). As noted, in the USA, homicide in general – and youth homicide in particular – is highly concentrated in communities with high levels of economic deprivation, joblessness, family disintegration, and racial segregation (Sampson and Wilson 1995). For example, the period of the youth homicide epidemic in the late 1980s corresponded to major changes in structural disadvantage in urban areas that weakened families and institutions responsible for social services and control.

Communities with higher levels of concentrated disadvantage often have fewer resources for protecting youth from involvement in illegal and dangerous activities, preventing proliferation of gangs, or mitigating the development of illegal drug markets. In their study of 83 large US cities for the years of 1970–2000, McCall and her colleagues (2008) found that an index of “resource deprivation” provided some of the strongest associations with increases in homicide rates within cities. Cities with decreases in the percent of families living in poverty, income inequality, and percent of children not living with both parents, coupled with increases in median family income, experienced decreases in their overall homicide rates. Each component also was independently and significantly associated with changes in city homicide rates.

Although black youth account for a disproportionate share of homicide arrests compared to their representation in the US population (e.g., Puzzanchera 2009), much of this may be explained by disadvantage. As in many other countries, structural disadvantage – and a corresponding lack of opportunity – is often particularly severe in communities of color. In their study of how city-level changes in social and economic disadvantage contribute to increases in youth homicide victimization for 15–19-yearold juveniles and 20–24-year-old young adults from 1990 to 2000, Strom and MacDonald (2007) found that increases in social and economic disadvantage were positively associated with increases in Black teenage, Black young adult, and White teenage homicide rates, independent of other factors. In general, cities with increasing economic disadvantage and family instability showed increases in youth homicide for both Blacks and Whites, independent of drug arrest rates, ethnic heterogeneity, region, and population density.

Illegal Drug Markets And US Homicide

Similar effects have been found for the influence of illegal drug markets on youth homicide. Analyzing the role of illegal drug markets in the 1980s–1990s youth homicide epidemic, Ousey and Lee (2002) used longitudinal data to examine whether within-city variation in the sale or manufacture of cocaine/opiates from 1984 to 1997 was associated with within-city variation in homicide perpetration rates during the period. Ousey and Lee modeled city-specific changes in drug market activity and homicide perpetration rates for 15–29-year-olds and the effect of between-city variation in levels of resource deprivation and found that levels of concentrated disadvantage within cities also influenced the relationship of drug market activities and homicide. Cities with higher levels of resource deprivation had significantly stronger relationships between illegal drug market activities and homicide perpetration by 15–29-year-olds. In cities with the lowest levels of resource deprivation, the relationship became negative.

The most popular explanation offered for the suddenness and extremity of the homicide epidemic was the explosion of illegal drug markets linked to the introduction of crack cocaine in the 1980s (Baumer et al. 1998; Blumstein and Wallman 2006). This theory was used to explain the sharp decline in the epidemic as well (e.g., Blumstein and Rosenfeld 1998). Although subsequent empirical studies documented the importance of illegal drug markets to the 1980s–1990s epidemic, studies by Ousey and Lee (2002) and others demonstrate that the effects were highly influenced by social context. A growth in drug-related arrests during this period was related to higher homicide arrest rates, but only for non-Latino White juveniles (see Ousey and Augustine 2001). In their study of changes in overall homicide rates from 1970 to 2000 in 83 large cities, McCall et al. (2008) found that the “drugs and violence” link suggested as a cause for the spike in youth homicide during the mid-1980s and early 1990s did not explain the decline in those rates during the last half of the 1990s. Similarly, Baumer’s (2008) analyses suggested that crack cocaine was not a strong predictor of the decline in the 1990s.

Gang Presence/Activities And US Homicide

Another major challenge for US cities over the past several decades has been gang-related violence. In 2007, 86 % of agencies serving large US cities reported gang problems, in contrast to 50 % of agencies serving suburban areas and 35 % of agencies serving smaller cities. Based on their 2007 survey, Egley and O’Donnell (2009) estimated that there were more than 27,000 active gangs and approximately 788,000 gang members in the United States, with 80 % of gang members residing in large cities and suburban counties. Reports of gang-related homicides also tend to concentrate in America’s most populous cities. As with other youth crime indicators during this period, one in five large cities reported an increase in gang homicides in 2007 compared with the previous year. Approximately two in five large cities reported increases in other violent offenses by gang members. Adolescent gang members account for a disproportionate share of serious violent offenses committed by juveniles. Longitudinal studies conducted by Thornberry and colleagues (Thornberry 1998; Krohn and Thornberry 2008) document that youth are more prone to serious and violent offenses when actively involved with a gang than before or after that affiliation.

Firearm Availability And US Homicide

The presence of weapons – particularly firearms – also has been associated with shifts in US homicide trends as well as the youth homicide epidemic. Blumstein speculated that, as adult sellers dominating drug markets were imprisoned, crack markets were increasingly staffed by young inexperienced street sellers who, lacking maturity and other skills, resolved conflicts with overwhelming force, often through the use of firearms (Blumstein 1995, pp. 29–31). However, in Baumer’s recent (2008) analysis of data from 114 large US cities for the years of 1980–2004, his measure of firearm prevalence was not significantly associated with either youth or adult homicide.

Alcohol Availability And US Homicide

Finally, as Parker and colleagues note (2011), the relationship between homicide and alcohol availability is well established by empirical studies in North America, Europe, and some parts of Asia. Findings linking youth homicide and the availability of alcohol for purchase are mostly missing from the literature, however, especially at the city level and across long time periods, leaving a critical gap in our understanding of homicide perpetration in the USA.

Combining Key Factors Affecting Youth Homicide Trends: 1984–2006

Based on these findings and gaps in the literature, Browne, Williams, Parker, Strom, and Barrick conducted a National Institute of Justice-funded study, Anticipating the Future Based on Analysis of the Past: Intercity Variation in Youth Homicide, 1984–2006, analyzing trends and predictors of youth homicide perpetration rates among juvenile and young adults 13–17 years old and 18–24 years old in the 91 largest US cities (per 1980 Census) – the first major study to focus exclusively on intercity variation in youth homicide trends. This study (a) analyzed temporal trends within cities during the dramatic escalation, decline, and subsequent increase in youth homicide rates; (b) explored whether the factors discussed above accounted for variation in youth homicide trends between cities; and (c) assessed whether the predictors applied equally to juvenile and young adult perpetration. The goal was to identify city characteristics associated with increases in homicides by juveniles and young adults in large US cities so future increases might be anticipated and prevented.

Measures

The research team created a measure of structural disadvantage that included traditional risk factors as well as illegal drug activity, gang presence-activity, firearm availability, and alcohol availability. Data on youth homicide were drawn from the Supplementary Homicide Report (SHR) – a component of the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting Program. The study compensated for missing data on offender characteristics in the SHR by using multiple imputation techniques. After data were multiply imputed, incidents were aggregated to the city level for calculations. (See Parker et al. 2011: 507–510 for details on study methods.) Analyses included only murder and nonnegligent manslaughter and excluded homicide by negligence or justifiable homicides, since those homicides are relatively rare and are not included in most definitions of criminal homicide. Analyses of incident-level data also included only incidents involving a single victim and a single perpetrator; again homicides with multiple perpetrators or victims are relatively rare. Data on the availability of alcohol within cities were gathered from the US Census of Economic Activity conducted every 5 years and were used to construct an annual time series for the density of retail alcohol outlets in each city. Other city-level characteristics – structural disadvantage, drug market activities, gang presence-activity, and firearm availability – were derived from the US Census County and City Data Books, the SHR, the annual National Youth Gangs Survey (Egley et al. 2006), and the Vital Statistics Multiple Cause of Death File, respectively.

Analyses

Analyses utilized Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM), effectively used in city-level homicide research by Ousey and Lee (2002) and others. This approach was selected since a set of models for nested data can be estimated simultaneously, such that the influence of the independent predictors of the dependent variable is estimated and, simultaneously, factors that measure differences among the clusters of cases at level 2 are assessed for their influence on the effects of the independent variables at the lower level at level 1. A second multilevel analytical approach, pooled cross-sectional time series (c.f. McCall et al 2008), was used to provide an additional analytical procedure with enhanced statistical power compared to HLM.

Key Findings

Using this combined measure of traditional risk factors, drug activity, gang presence-activity, and firearm and alcohol availability revealed that, for the two age groups, homicide perpetration among juveniles and young adults followed the same general trend between 1984 and 2006 in large US cities, with a sharp increase in youth homicide perpetration rates during the epidemic of the late 1980s to early 1990s, a significant downturn from 1994 to 1999, and a significant upturn from 2000 to 2006. For the two periods of increase, factors significantly associated with the perpetration of lethal violence during the years of the homicide epidemic were also associated with the subsequent increases in rates of homicides in 2000–2006.

Structural disadvantage and gang presence-activity in cities had consistent and significant effects on trends in youth homicide perpetration during the youth homicide epidemic and the increases in 2000–2006 as well. The greater the structural disadvantage and gang presence-activity within a city, the greater the escalation in youth homicide rates during the epidemic years. Although not as strong, this pattern also held for intercity variation during the increase in youth homicide perpetration in 2000–2006. Drug market activity within cities and over time also demonstrated consistent and positive effects on trends in youth homicide perpetration for 13–17-year-olds and 18–24-year-olds in the pooled cross-sectional time series analysis with its greater statistical power (but not in the HLM analysis).

Firearm availability in the pooled cross-sectional time series analysis (but not the HLM analysis) demonstrated significant and positive effects on trends in homicide perpetration for young adults ages 18–24 years old over the period. No statistically significant effects for firearm availability were found for younger perpetrators 13–17 years of age. Alcohol availability did show consistent effects on youth homicide perpetration for both juveniles and young adults, based on the measure of the density of alcohol retail outlets in cities (Parker et al. 2011). Similar effects have been found for adults in national as well as neighborhood level quantitative studies, but this is the first study to report this for these age groups. The proportion of young people in the population did not have statistically significant effects on city rates of juvenile and young adult homicide perpetration.

There are a number of limitations to the study. The models in these analyses used macro-level measures that did not directly capture dynamics at the neighborhood or individual level. Additionally, the use of city-level data, while advantageous for comparing risk factors between cities, does not capture within-city variations. For example, these measures do not indicate whether certain neighborhoods within a city have high or low levels of disadvantage, gang presence, or alcohol availability. However, the youth homicide study identified significant explanatory predictors across a particularly significant 23-year time period using two analytic strategies and multiple variables to enhance understanding of factors influencing increases in US homicide perpetration for two critical age groups.

Implications And Future Directions

As noted, the ultimate goal of the youth homicide study was to identify city characteristics associated with increases in homicides by juveniles and young adults in large US cities so that federal, state/regional, and local criminal justice leaders, practitioners, and advocates could develop and utilize a data-driven approach for monitoring and preparing solutions for crime involving youth. Study results documented that the increase in youth homicide perpetration in the USA from 2000 to 2006 occurred for both juveniles and young adults. Findings also showed that, despite occurring in two distinct time periods, there were consistent predictors for escalation in the perpetration of lethal violence by juveniles and young adults.

This is important from a preparedness and a prevention standpoint. The strong and consistent findings on the association of structural disadvantage and violent crime across multiple years in both age groups and periods of escalation are of particular relevance. Given the severe economic challenges facing the US and many other countries and their impact on urban areas, city officials, police departments, legislators, and community leaders need to be particularly vigilant to offset an escalation in lethal violence by youth related to resources and budgetary priorities over time.

The presence of gangs, drugs, and alcohol at the city level also are key components in cross-sectional and over time variation in youth homicide. Residents in communities with concentrated levels of unemployment and severe economic deprivation may be less able to handle delinquent youth, control illicit activities, or offer juveniles and young adults positive alternatives. Results of the youth homicide study’s pooled time series analysis show significant effects for gang presence-activity, drug-related activities, and (for 18–24-year-olds only) firearm availability across 23-year period, highlighting the importance of preventive efforts in these areas. Findings on the impact of alcohol availability for both age groups also suggest a point of intervention, by indicating that reduction in the density of retail alcohol outlets in urban areas and neighborhoods may be an effective tool for violent crime reduction among youth.

Finally, in the youth homicide study, there were marked similarities in city-level explanatory predictors associated with juvenile and young adult violence trends. Although Butts and Snyder (2006) encouraged the inclusion of 18–24-year-olds in studies of youth homicide trends, to our knowledge, this is the first study that examines lethal youth violence trends and their city-level predictors separately for juveniles (ages 13–17) and young adults (ages 18–24). The importance of the identified risk factors for both age groups is not surprising. There is considerable overlap in the interactions of teenagers and young adults in urban settings, including family and other social interactions as well as local gang and drug market activities. Much of the gang literature describes age-integrated gangs composed of juveniles and young adults. Homicide data also consistently documents a substantial crossover between juvenile and young adult victims and offenders (e.g., Cook and Laub 1998). It is critical that any interventions or initiatives seeking to prevent or reduce youth violence not simply focus on juveniles under age 18. They must also address criminally involved young adults with whom juveniles come in contact if the younger youth are to be deterred and protected.

By identifying and better understanding factors related to increases in youth homicide perpetration, policy makers, researchers, and community leaders can develop more effective and targeted strategies for responding to “at-risk” juveniles and young adults before periods of escalation (e.g., although a downturn has been reported in some national rates from 2007 through 2008 for violent crimes by youth, the perpetration rate for homicide by Black male juveniles ages 14–17 continued to increase from 2002 to 2008: Cooper and Smith 2011).

Empirical findings can be utilized as a first step by cities, states, and practitioners and policy makers to:

- Support At-risk Youth, Particularly Youth Living in Structurally Disadvantaged Neighborhoods. It is critical that proactive resources and programs for at-risk youth be increased by using comprehensive and integrated community-level, school-level, family-level, and individual-level interventions designed to strengthen young people’s “core competencies” as well as the social contexts in which they reside. As Williams, Guerra, and their colleagues have noted, having such supports will help juveniles and young adults more effectively – without violence and other illegal activities – “beat the odds” (Kim et al. 2008; Guerra and Bradshaw 2008). Empirical studies document that, even in the face of severe disadvantage and pervasive danger, most young people accomplish the developmental tasks necessary to withstand the risks and live productive, healthy, and responsible adult lives (e.g., Elliott et al. 2006).

- Create Prevention Initiatives and Programs That Target Young Adults Ages 18–24 as Well as At-Risk Juveniles. Results of the youth homicide study clearly demonstrate that juvenile and young adult trends in homicide perpetration are influenced by similar factors (with the exception of firearms availability). As a result, interventions – whether in the form of policing initiatives or community-based prevention strategies – should not exclude young adults. For example, this is the case with under age access to alcohol, since half of the population at risk in the 18–24 age group is below the legal minimum purchase age for alcohol. Enforcing existing laws with regard to under age access may have an important preventative impact on younger and older age groups.

- Develop Comprehensive and Multidisciplinary Approaches for Addressing Gangs. Findings from the youth homicide study and other empirical research also demonstrate the importance of gang presence and activity in influencing increases in fatal violence by juveniles and young adults. It is urgent that federal, state or region, and city policy makers work with law enforcement and crime prevention experts to assess gang activity proactively and incorporate that knowledge not simply into police planning but also into creative citywide and regional initiatives for community-based and social policy interventions.

- Inform Preparedness and Prevention Activities More Effectively. Federal and local leaders should develop and utilize more data-driven approaches for enhancing crime preparedness and prevention activities. These activities could then be tied directly to the deployment and strengthening of policing and crime prevention resources in a more efficient manner, based on identified predictors of lethal youth violence during the escalation period of 1984–1993 and the relevance of those predictors for increases in 2000–2006. At the federal level, this would include compiling the necessary data sources and identifying cities particularly at risk of youth homicide increases based on past and current structural conditions and city-specific trends. At the local level, mayors, police chiefs, and other agencies charged with responding to or preventing crime should consistently review and analyze the data for their jurisdiction to identify emerging patterns and concerns.

- The type of data collection and analysis we recommend would involve (1) analyzing multiple years of data to explore past and emerging city-based trends and (2) the use of data sources in addition to police crime data, including key economic and social indicators as well as specific measures of the prevalence of gang presence-activity, drug-related activity, and alcohol outlet density in the city. The timeliness and quality of crime and structural indicator data must be improved as well, so that these measures are useful for resource deployment and prevention.

- Improve Quality of Crime and City-level Indicator Data. There also is a critical need to develop improved measures. The goal is to develop measures that can be standardized across jurisdictions and are as independent as possible of police activities and initiatives. One mechanism is to develop measures through survey data collection processes that monitor levels of gang activity or drug activity in specific communities. The regular collection of information using these types of approaches may be cost-prohibitive for some jurisdictions, however. Ultimately, from a national policy standpoint, decisions must be made as to whether the benefits associated with increased resources for collecting independent measures provide a significant return in (a) understanding these phenomena within and across cities and (b) monitoring and intervening effectively over time. In the absence of improved measures, many of the surprises associated with imprecise measures will continue.

Since the early 1980s, responses to crime in the United States have centered on law enforcement, sentencing, and incarceration or detention. A growing body of criminal justice literature suggests that investments in policing and other official forms of social control will have disappointing results unless the preconditions of structural disadvantage and attendant problems are addressed. For communities, states, regions, and nations, the benefits of preventing criminal activities and their outcomes among youth will far outweigh the investments required for proactive support.

Bibliography:

- Baumer EP (2008) An empirical assessment of the contemporary crime trends puzzle: a modest step toward a more comprehensive research agenda. In National Research Council Committee on Understanding Crime Trends (eds) Understanding crime trends: Workshop Report. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC, pp 127–176

- Baumer EP, Lauritsen JL, Rosenfeld R, Wright R (1998) The influence of crack cocaine on robbery, burglary, and homicide rates: a cross-city, longitudinal analysis. J Res Crime Delinq 35:316–340

- Blumstein A (1995) Youth violence, guns, and the illicitdrug industry. J Crim Law Criminol 86:10–36

- Blumstein A, Rosenfeld R (1998) Explaining recent trends in U.S. homicide rates. J Crim Law Criminol 88:1175–1216

- Blumstein A, Wallman J (eds) (2006) The crime drop in America (rev. edn). Cambridge University Press, New York

- Blumstein A, Rivara FP, Rosenfeld R (2000) The rise and decline of homicide—and why. Annu Rev Public Health 21:505–541

- Browne A, Williams KR (1993) Gender, intimacy, and lethal violence: trends from 1976–1987. Gender Soc 7(1):78–98

- Browne A, Williams KR, Dutton DG (1999) Homicide between intimate partners: a 20-year review. In: Smith D, Zahn M (eds) Homicide: a sourcebook of social research. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

- Butts JA, Snyder HN (2006) Too soon to tell: deciphering recent trends in youth violence. (Issue Brief No. 110). Retrieved from University of Chicago, Chapin Hall Center for Children website: http://www.nationalgangcenter.gov/Content/Documents/Deciphering-RecentTrends-in-Youth-Violence.pdf

- Cook PJ, Laub JH (1998) The unprecedented epidemic in youth violence. Crime Justice 24:27–64

- Cooper AC, Smith EL (2011) Homicide trends in the United States, 1980–2008: annual rates for 2009 and 2010 (Report No. NCJ 236018). Retrieved from Bureau of Justice Statistics website: http://bjs.ojp. usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/htus8008.pdf

- Egley A, Howell JC, Mayor AK (2006) National youth gang survey, 1999–2001. US Department of Justice, OJJDP, Washington, DC

- Egley A, O’Donnell CE (2009) Highlights of the 2007 national youth gang survey (Report No. NCJ 225185). Retrieved from Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention website: https://www.ncjrs.gov/ pdffiles1/ojjdp/225185.pdf

- Elliott DS, Menard S, Rankin B, Elliott A, Wilson WJ, Huizinga D (2006) Good kids from bad neighborhoods: successful development in social context. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY

- Flewelling R, Williams KR (1999) Categorizing homicides: the use of disaggregated data in homicide research. In: Smith D, Zahn M (eds) Homicide: a sourcebook of social research. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

- Fox JA, Zawitz MW (2002) Homicide trends in the United States. Retrieved from Bureau of Justice Statistics website: http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/ htius.pdf

- Guerra NG, Bradshaw CP (eds) (2008) Core competencies to prevent problem behaviors and promote positive youth development [Special issue]. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development 122:1–92

- Kim T, Guerra NG, Williams KR (2008) Preventing youth problem behaviors and enhancing physical health by promoting core competencies. J Adolesc Health 43:401–407

- Krohn MD, Thornberry TP (2008) Longitudinal perspectives on adolescent street gangs. In: Liberman AM (ed) The long view of crime: a synthesis of longitudinal research. Springer, New York

- Land KC, McCall PL, Cohen LE (1990) Structural covariates of homicide rates: are there any invariances across time and space? Am J Sociol 95:922–963

- McCall PL, Parker KF, MacDonald JM (2008) The dynamic relationship between homicide rates and social, economic, and political factors from 1970–2000. Soc Sci Res 37:71–735

- McDowall D, Loftin C (2009) Do U.S. city crime rates follow a national trend? The influence of nationwide conditions on local crime patterns. J Quant Criminol 25:307–324

- Messner SF, Deane GD, Anselin L, Pearson-Nelson B (2005) Locating the vanguard in rising and falling homicide rates across U.S. cities. Criminology 43:661–696

- Moore MH, Tonry M (1998) Youth violence in America. Crime Justice 24:1–26

- Ousey GC, Augustine MC (2001) Young guns: examining alternative explanations of juvenile firearm homicide rates. Criminology 39:933–967

- Ousey GC, Lee M (2002) Examining the conditional nature of the illicit drug market-homicide relationship: a partial test of the theory of contingent causation. Criminology 40:73–102

- Parker RN, Rebhun LA (1995) Alcohol and homicide: a deadly combination of two American traditions. SUNY Press, New York, NY

- Parker RN, Williams KR, McCaffree KJ, Acensio EK, Browne A, Strom KJ, Barrick K (2011) Alcohol availability and youth homicide in the 91 largest US cities, 1984–2006. Drug Alcohol Rev 30:505–514

- Puzzanchera C (2009) Juvenile Arrests 2008 (Report No. NCJ 228479). Retrieved from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention website: https:// www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/228479.pdf

- Sampson RJ, Wilson WJ (1995) Toward a theory of race, crime and urban inequality. In: Hagan J, Petersen R (eds) Crime and inequality. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA, pp 27–54

- Snyder H, Sickmund M (2006) Juvenile offenders and victims: 2006 national report (Report No. NCJ 212906). Retrieved from Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention website: http://www. ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/nr2006/downloads/NR2006.pdf

- Strom KJ, MacDonald JM (2007) The influence of social and economic disadvantage on racial patterns in youth homicide over time. Homicide Stud 11:50–69

- Thornberry TP (1998) Membership in youth gangs and involvement in serious and violent offending. In: Loeber R, Farrington DP (eds) Serious and violent juvenile offenders: risk factors and successful interventions. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp 147–166

- Williams KR, Flewelling R (1988) The social production of criminal homicide: a comparative study of disaggregated homicide rates in American cities. Am Sociol Rev 53:421–431

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.