This sample Early Childhood Education Practice Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Like other free research paper examples, it is not a custom research paper. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our custom writing services and buy a paper on any of the education research paper topics.

How should 5-year-olds spend their day? Should taxpayers fund preschool play time? Should 4-year-olds be expected to name the letters of the alphabet? Should they be expected to count to 10 or 20? These questions reflect debates about the purposes and goals of early childhood education. The most influential organization addressing these concerns is the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC), a professional association representing over 100,000 early childhood professionals. NAEYC’s efforts have shaped how people think about the education of young children both in the United States and abroad (Raines & Johnston, 2003). The organization has influenced policy and practice by publishing position statements and research briefs designed to influence policy and legislation, by developing a gold-standard accreditation system for private and public child care centers and schools, and by providing professional development and literature for the early childhood community.

In 1987 NAEYC published its seminal position statement, NAEYC Position Statement on Developmentally Appropriate Practices in Early Childhood Programs Serving Children From Birth Through Age 8 (Bredekamp, 1987). The statement was designed to guide administrators of early childhood centers seeking NAEYC accreditation and to clarify the concept of developmentally appropriate practice (DAP); but it did much more. According to Raines and Johnston (2003), the 1987 position statement:

Irrevocably changed the thinking and discourse about practices in early childhood programs. Since its recent entry into the professional education lexicon, the term developmentally appropriate practices and the concept it represents have been adopted and used extensively by educators, policy makers, and businesses. Both the concept and the term have affected early childhood program practices; national, state, and local policies for curriculum and assessment; marketing of commercial early childhood materials and programs; and standards for early childhood educator preparation. (p. 85)

In 1997 the statement was revised and expanded, and it is currently undergoing a second revision.

NAEYC’s advocacy has focused national attention on the need for quality early childhood education. Still, DAP is controversial. According to NAEYC, developmentally appropriate practice is an approach to early childhood education that employs “empirically based principles of child development and learning” (Bredekamp & Copple, 1997, p. 9). Such a proposition seems inarguable. How can anyone dispute that the education of young children should be based on scientifically derived knowledge? But the matter is not so simple. The universal acceptance of DAP has faced significant challenges (Dickinson, 2002). DAP casts early childhood education as a dichotomy in which practice is either developmentally appropriate or inappropriate. Many in the early childhood field object to this dichotomized way of thinking about educating children. DAP is also plagued by definitional, empirical, and theoretical difficulties. These difficulties result in misunderstandings about and misapplications of DAP (Raines & Johnston, 2003). Unfortunately, most people who work with young children are not well-trained (Karp, 2006), so early childhood practitioners often lack the expertise to adapt DAP. Finally, many in the early childhood field argue that DAP reflects Caucasian, middle- and upper-class values and object to labeling other cultures’ ways of raising children as inappropriate (Delpit, 1988; Lubeck, 1998; O’Brien, 1996).

This research-paper discusses these challenges and makes recommendations for reconceptualizing early childhood best practice. NAEYC has responded to previous critiques by revising the position statement, which it intends to do every 10 years. Although regular revision is helpful, it is unlikely that everyone in NAEYC’s broad sphere of influence will simultaneously revise their beliefs and practices. Despite many helpful changes in the 1997 revision, many of the ideas found in the 1987 statement (such as an age-based definition of DAP) still affect thinking about early childhood education. Thoughtful analysis of DAP must consider how the concept has been articulated and used from its inception. Therefore, this analysis considers DAP as a conceptual whole: as it is represented in both the 1987 and 1997 statements (and their accompanying documents) and how it is generally used in early childhood research, practice, and policy. The framers of DAP recognize that educating young children is a messy, complex affair and welcome discussion about DAP (Bredekamp & Copple, 1997). This research-paper hopes to contribute to the dialogue.

Dichotomies and Developmentally Appropriate Practice

Sorting ideas into categories is one of the earliest cognitive skills humans develop. Dichotomous categorizing (this is an animal; this is not an animal) is prerequisite to more elaborate and complex concept formation. Thus, when explaining a new concept, dichotomies are intuitively appealing. For this reason, DAP is outlined in a dichotomous framework (Bredekamp & Copple, 1997). According to Bredekamp and Copple, “People construct an understanding of a concept from considering both positive and negative examples. For this reason the chart [describing DAP] includes not only practices that we see as developmentally appropriate, but also practices we see as inappropriate or highly questionable for children of this age” (1997, p. 123).

As appealing as dichotomies are, there are compelling reasons to avoid them. First, evidence rarely supports dichotomous explanations of development (Gutierrez & Rogoff, 2003). For example, the DAP statements label preschool programs that focus on pre-academic skills inappropriate (Bredekamp & Copple, 1997). Yet, many preschoolers can successfully acquire such skills (Kessler, 1991). Second, dichotomies are merely prerequisites to more complex thinking. Since they artificially cast phenomena as either/or categories, they reduce complexity of thought. Such narrow thinking interferes with developing rich, evolving conceptions of young children’s development. For example, although it would be inappropriate to use stickers or candy to teach typically developing 3-year-olds to make eye contact when greeting friends, using such artificial reinforcers may be an appropriate intervention for a child with an autism spectrum disorder. But once the child has acquired the skill, continued use of reinforcers would be inappropriate. Thus, using artificial reinforcers is not categorically appropriate or inappropriate: It is simply a method that can be effective under certain circumstances. Meeting children’s diverse needs requires flexible thinking. Recognizing this need, the authors of the 1997 statement argue to end dichotomous thinking about educating young children (Bredekamp & Copple, 1997). Still, dichotomous thinking is at the core of DAP. DAP represents one side of an either/or debate between two theoretical schools of thought: behaviorism and constructivism.

Behaviorism explains learning and development in terms of responses to environmental reinforcers and punishers and carefully manages the use of time (Skinner, 1984). Therefore behavioral methods carefully control environmental factors such as the delivery of reinforcers and the pace of instruction. From a behavioral perspective, adequate reinforcement plus sufficient time leads to increased learning. Behavioral methods were successfully used during World War II to rapidly train a victorious U.S. military. Shortly after the war, with the launch of the Russian satellite Sputnik, the United States began to fear that the Soviet Union was becoming the world’s technological leader. This fear spawned reform movements designed to fix American public schools and reestablish the dominance of the United State’s in the global economy. Demonstrated success during WWII solidified behavioral approaches as the methodology of choice for American’s educational reform efforts.

After initial enthusiasm, the reform momentum of the 1960s and 1970s faded, but the idea that U.S. schools needed to be fixed did not. Recent reform efforts have varied in their support for or opposition to behavioral classroom methods. Educational reform in the 1980s combined emerging cognitive theories such as information processing with behaviorism’s emphasis on efficiency, promoting the idea that those in public schools— teachers, students, administrators—need to do more and need to achieve more. With demands to do more and achieve more, it logically followed from behavioral theory that children and teachers need more time. Schoolwork was sent home to be completed in the evening and on weekends, school days were lengthened, and so was the school year. But even with lengthened days and years there is never enough time to do everything one is expected to do in a public school classroom. With the length of the school day and year maximized, extending academic instruction to younger children logically follows. If there isn’t enough time to teach reading in first grade, perhaps reading instruction should start in kindergarten. Similarly, if there isn’t enough time to teach school routines and letter recognition in kindergarten (because the day is filled with learning to read and write), perhaps these skills should be taught in preschool. After all, note those who argue for more academic rigor, many 4- and 5-year-old children capably acquire these academic skills (Stipek, 2006).

In contrast to those who promote more academic rigor at early grade levels, many early childhood educators champion the benefits of an unhurried, unstructured early childhood experience. From their perspective, engaging preschool and kindergarten-age children in direct instruction of academic skills pushes children beyond their developmental level and can negatively affect long-term academic outcomes. The 1987 statement clarified NAEYC’s position that behaviorally controlled learning environments are inappropriate for young children and promoted a very different theoretical orientation called constructivism. Constructivism is the theoretical belief that children are naturally curious and actively construct knowledge. Children act upon their environments rather than their environments acting upon them. Constructivism is a cognitive theory that conceptualizes learning as changes in mental representations and associations rather than changes in behavior. Jean Piaget, the best known constructivist theorist, is referenced frequently in the DAP statements. The 1987 statement uses Piaget’s stages of cognitive development (Piaget, 1952) in its definition of DAP and articulates a Piagetian view of learning: “Knowledge is not something that is given to children as though they were empty vessels to be filled. Children acquire knowledge about the physical and social worlds in which they live through playful interaction with objects and people” (Bredekamp, 1987, p. 52). The 1997 statement also describes an overt constructivist position: “Children are active learners, drawing on direct physical and social experience as well as culturally transmitted knowledge to construct their own understandings of the world around them” (Bredekamp & Copple, 1997, p. 13).

Educational practices based on constructivist theory look very different than those based on behaviorism. Classrooms and curricula based on behavioral influences emphasize efficiency and thus require structured environments. Classroom space and time is well-defined with specific activities occurring in specific areas according to schedule. Constructivist classrooms are considerably more unstructured. Space is loosely arranged with children free to engage in a variety of activities in areas of their choosing. Though teachers establish routines for snacks, bathroom trips, story time, and indoor and outdoor play, activities are not governed by strict schedules. In theory, children’s interests and preferences influence allocation of time and resources.

The teacher’s role is also different in constructivist and behavioral classrooms. Constructivism emphasizes children as agents of their own learning. Adults serve as facilitators and provide environments enriched with opportunities for children to experiment with objects and satisfy their own curiosity. The 1987 statement says, “In develop-mentally appropriate programs, adults offer children the choice to participate in a small group or in a solitary activity [and] provide opportunities for child-initiated, child-directed practice of skills as a self-chosen activity” (Bredekamp, 1987, p. 7). Conversely, behaviorally organized classrooms are teacher-directed. The schedule, learning goals, and activities are chosen and monitored by the teacher. Children’s choices are often limited to selecting from a range of predefined choices (“You may look at books in the reading nook or on the patio”).

Curriculum also differs between constructivist and behavioral classrooms. Constructivists use emergent curriculum that allows children to use various materials and methods rather than copying teacher-made examples. Consistent with constructivism, NAEYC considers it inappropriate for adults to reject “children’s alternative ways of doing things” and to place great importance on children reproducing something the teacher has constructed (such as a holiday art project) or imitating the teacher’s way of performing a task (such as peeling or buttering bread or threading beads; Bredekamp & Copple, 1997, p. 127). Behaviorally-based programs use convergent curriculum that incorporates predefined learning activities with teacher-defined correct responses that are the same or similar for all the children. Such curricula are identified as inappropriate by NAEYC for all young children up to and including Grade 3.

Finally, classrooms based on constructivist and behavioral theory differ in the use of play versus academic work. Piaget (1952) emphasized children’s need to engage in object play to develop cognitively. Thus constructivist preschool and kindergarten classrooms are designed to facilitate children’s exploration and discovery. Indeed, play is viewed by many child advocates as “absolutely essential to advancing children’s development” (Kagan & Lowenstein, 2004, p. 59). The 1987 statement describes play as “an essential component of developmentally appropriate practice” (Bredekamp, 1987, p. 3) and calls for a 1-hour minimum devoted to free play daily. Unlike constructivist-based programs, in a behavioral framework play is often viewed as an encroachment on academically engaged time. Play may be used as a break from more valued academic work, as an opportunity for physical development, as a reward for academic productivity, or as a way to help children enjoy school and thus reinforce achievement. But in a behavioral frame, play is not inherently valued as a mechanism of learning and development.

Unfortunately, framing early childhood best practice as a dichotomy between appropriate constructivist methods and inappropriate behavioral methods does not allow the field to develop rich, nuanced conceptions of how best to educate young children. Alternative ways of conceptualizing professional practice will be discussed later.

DAP and Cultural Compatibility

Another controversial DAP issue is the claim by critics that many practices identified as developmentally inappropriate are time-honored ways of raising children in many cultures. Some argue that DAP represents Caucasian, European American child-rearing practices rather than universal developmental principles. They note that many indigenous cultures, such as Native Hawaiian and Native American, raise children to be cooperating members of an extended family and close-knit community, rather than stressing independence and autonomy. In many cultures, it is unacceptable for young children to choose not to participate in a teacher-initiated activity. Similarly, the idea that classrooms should be “child-centered” with “child-directed” activities or that “adults [should] respond quickly and directly to children’s needs, desires and messages” (Bredekamp, 1987, p. 9) does not align with the way many cultures raise children. In many cultures, it is expected that children respond quickly and directly to adults’ messages.

The 1997 DAP revision emphasizes the need for culturally sensitive practice (Bredekamp & Copple, 1997, pp. 41-52); however, the revision did not address the concern that DAP’s fundamental philosophy defining children’s role in relationship to adults is not compatible with many families’ cultural values and practices (Goldstein & Andrews, 2004; Gutierrez & Rogoff, 2003). Critics also question the application of developmental research findings to all children. Piaget studied exclusively northern Europeans, primarily his own children. Critics argue that one cannot assume that findings based on such a narrow population adequately describe all children.

DAP Definitional, Empirical, and Theoretical Difficulties

A final area of difficulty for DAP concerns definitional ambiguity, shaky empirical support, and a narrow theoretical focus.

Definitional Difficulties

Both terms used to define DAP, developmentally and appropriate, are ambiguous, leading to conundrums. For example, much of DAP recommendations are simply good teaching practices—for children of all ages. Referring to these practices as developmentally appropriate for young children implies that these practices are not necessarily appropriate for older students. The word appropriate poses its own dilemmas. What is appropriate to one may be inappropriate to another. There are ways around this ambiguity. Other professions do not define practice by the notion of appropriateness. There is no such thing as legally appropriate practice or medically appropriate practice. Rather, most professions embrace a best practice approach in which minimal standards and ideal guidelines are articulated. Adopting a best practice framework would reduce ambiguity and provide a way to identify differences in quality while reserving the label inappropriate for those practices that are unambiguously unacceptable for all children (e.g., abuse and neglect).

Fuzzy definitions also affect recommendations for practice. For example, the 1987 statement says, “Children of all ages need uninterrupted periods of time to become involved, investigate, select, and persist at activities” (Bredekamp, 1987, p. 7), but the frequency and duration of “uninterrupted periods of time” is left undefined. Similarly, the 1997 revision identifies what is inappropriate for 6- to 8-year-olds: “Teachers lecture to the whole group and assign paper-and-pencil practice exercises or work sheets to be completed by children working silently and individually at their desks” (Bredekamp & Copple, 1997, p. 165). Does the statement mean such direct instruction, used daily in thousands of primary classrooms around the world, is categorically inappropriate? Oddly, the same page identifies direct instruction as developmentally appropriate. In another example, the 1987 statement encourages adults to “move quietly” in early childhood classrooms (Bredekamp, p. 9), and the 1997 statement lists as inappropriate a classroom in which the noise level is “stressful and impeding conversation and learning” (Bredekamp & Copple, p. 125). Yet, two pages later the 1997 statement says that it is inappropriate when “teachers make it a priority to maintain a quiet environment” (p. 127).

These contradictions result in real problems. For example, early childhood practitioners must wrestle with the controversy over phonics-based and whole language literacy instruction. Traditional instruction relies on basal readers and teacher-directed, behavioral methods. Whole language, a constructivist approach, is broadly defined as one in which children construct meaning from text; use functional, relevant language; read “real” literature (as opposed to basal readers); and work in cooperative groups. Use of intact pieces of literature (rather than excerpts or abridgements), students’ selection of reading material, and integrated language arts instruction is attractive to many early childhood teachers (Jeynes & Little, 2000). According to a recent meta-analysis of early literacy studies, “the evidence suggests that low-SES [low-socioeconomic status] students in Grades K-3 benefit from basal instruction more than they do from whole language instruction. If the results of our synthesis accurately depict reality, using a whole language approach with low-SES children could widen the gap between advantaged and disadvantaged students” (Jeynes & Little, 2000, p. 31).

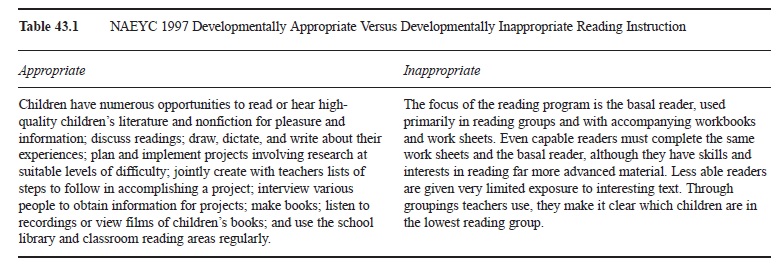

In a nod toward the growing evidence that many children, especially those from low-SES backgrounds, make more reading progress with basal instruction, the 1997 statement comments on the whole language versus phonics controversy by saying the two approaches are “quite compatible and most effective in combination” (Bredekamp & Copple, 1997, p. 23). As Table 43.1 illustrates, the same statement also identifies as appropriate practices consistent with a whole language approach and identifies as inappropriate practices commonly found in basal reader/phonics-based programs (Bredekamp & Copple, 1997, p. 172).

Table 43.1 NAEYC 1997 Developmentally Appropriate Versus Developmentally Inappropriate Reading Instruction

Table 43.1 NAEYC 1997 Developmentally Appropriate Versus Developmentally Inappropriate Reading Instruction

Thus, even though the 1997 editors call for an end to either/or thinking, they later articulate a clear declaration aligning whole language with best practice and basal reading programs with poor-quality teaching (e.g., disregarding students’ reading level and humiliating them). Missing from DAP is a discussion of how teachers might implement best practice strategies within a basal reading curriculum or how the two approaches might be combined.

Empirical Difficulties

There are two major weaknesses in the empirical support for DAP. First, many recommended strategies have no empirical basis. The 1997 statement claims 12 empirically derived principles which drive DAP recommendations. But more often than not, the guidelines make recommendations without providing empirical evidence, or, in many cases, merely provide a citation without making explicit links between research findings and the recommended strategy. As mentioned earlier, the 1987 statement says children of all ages “need uninterrupted periods of time to become involved, investigate, select, and persist at activities” without discussing how much time children need at various ages, how uninterrupted time benefits children’s development, or how research from the cited references supports the recommendation.

Further, when discussing how to respond to child misbehavior, the 1987 statement says, “Adults facilitate the development of self-esteem by respecting, accepting, and comforting children, regardless of the child’s behavior.” The statement goes on to describe respectful ways practitioners can interact with young children with which many would agree; however, there is no empirical support offered for the idea that comforting children regardless of their behavior “facilitates the development of self-esteem.” There is empirical evidence, however, that comfort or affection following misbehavior will likely increase misbehavior (Ormrod, 2008; Skinner, 1984).

The second weakness in the empirical support for DAP is inconsistent evidence linking DAP with improved educational outcomes. One challenge facing DAP is its claim that developmental research neatly translates into specific applications. But this is not the case. Most developmental research, especially the work of Piaget, occurred in controlled, laboratory settings that may not transfer to classrooms (Ormrod, 2008; Piaget, 1952). Contemporary clinical research also has limited direct applicability to educational settings. For example, despite the plethora of new information about brain development, relatively little is known about how young children actually learn (Neuman & Roskos, 2005). Thus, laboratory science is insufficient to inform effective classroom practice.

Findings from applied research on DAP are also insufficient. Studies in the 1990s seemed to support the effectiveness of DAP (Raines & Johnston, 2003). Researchers found a positive effect for cognition and emotional factors and that DAP was beneficial for all children regardless of race or socioeconomic backgrounds. Interestingly, research on social development—a primary focus for DAP classrooms—was inconclusive (Raines & Johnston, 2003). Recent research is not so favorable. For example, according to Van Horn, Karlin, Ramey, Aldridge, & Snyder (2005), DAP is related to better educational outcomes in some areas for some students, and other studies find little to no improvement in educational outcomes. Effects of develop-mentally appropriate versus developmentally inappropriate instruction vary by children’s grade level, gender, SES background, and ethnicity. Van Horn et al. (2005) elaborate: “The research assessing the effectiveness of DAP is highly inconsistent. These studies suggest differential patterns of outcomes for developmentally inappropriate practices (DIP) and DAP programs across academic subjects, in particular, that DIP may be more effective than DAP [italics added] for teaching reading skills” (p. 336).

Theoretical Difficulties

Theory is the foundation of any scientifically informed field of practice: it frames what is known, determines which questions need to be asked, and informs inferences about best practice. Much of the controversy regarding DAP can be traced to a particular view of development (espoused by Piaget and many of his contemporaries) called stage theory. In developmental theory stage is specifically defined as “a hierarchical progression of growth spurts with periods of plateau in between.” These growth spurts are marked by qualitative developmental change in which the quality (not merely the quantity) of a child’s skill or ability is distinctly different than it was previously. The child is able to think more complexly. For example, Piaget demonstrated that preschool children are unable to conserve mass, volume, or number—that is, they have difficulty maintaining a correct understanding of how much there is of something if the appearance of it changes though the amount remains the same. If one shows a 4-year-old a 3-inch tall, 2-inch diameter cylinder of clay, and then, while the child is watching, smashes the clay into a 1-inch thick pancake with a 4-inch diameter, the child will almost always say the pancake has less clay than the cylinder. After about the age of 6, when posed with the same dilemma, children roll their eyes at the absurd question and indicate that of course the amount of clay remains the same. The understanding that the amount of clay remains the same, despite its appearance, requires the child to attend to and process two dimensions (height and width) simultaneously and to also mentally reverse the process (unsmash the clay). Piaget also demonstrated that preschoolers reason from an egocentric point of view—they do not take another person’s perspective—and that adolescents reason abstractly whereas elementary age children do not.

In a strict stage theory, each stage starts and ends by attaining more complex forms of mental manipulation. In between these qualitative change bookends lies a developmental plateau—a period of time during which relatively little developmental growth occurs. According to stage theory, progression through stages occurs spontaneously according to genetically programmed timelines. It is believed that age-related development occurs with minimal variation regardless of environment. Thus, one expects certain skills and behaviors of a 3-year-old child and qualitatively different skills and behaviors of a 10-year-old. This belief in maturational unfolding also has implications for adult-child interactions. Because cognitive stages are thought to unfold without adult assistance, Piaget’s stage theory describes limited roles for adults in young children’s experiences. Piaget believed adult involvement in many aspects of children’s activities such as play, actually interferes with children’s development (Morrow & Schickedanz, 2006).

Recently, many have questioned the soundness of strict stage theory. Contemporary developmental research indicates developmental stages are not as closely related to age as previously thought (Bredekamp & Copple, 1997; Ormrod, 2008). For example, when conditions differ from Piaget’s controlled experiments, many preschool children readily conserve mass, liquid, and number. Further, many preschool children demonstrate an understanding of other people’s feelings, and elementary age children frequently demonstrate abstract thought. New brain research indicates children’s brains produce new neurons and neural connections, reorganize and strengthen existing neural pathways, and de-clutter brain structures by pruning superfluous neurons (Sousa, 2006) even when there is no observable evidence of cognitive growth. Research also indicates these neurological processes are highly affected by children’s experiences. Neurons that are not stimulated die off. Yet it may take weeks, if not longer, for neural connections to become organized and strengthened enough to support observable developmental change. Thus, periods of plateau during which development does not appear to advance is anything but stagnant. By waiting for observable readiness to emerge, as posited by stage theory, parents and educators may withhold development-promoting experiences. In deference to these empirical developments, the 1997 DAP statement notes that “there are serious limitations to the use of age-related data” (Bredekamp & Copple, p. 37). Still, the NAEYC list of empirically-based principles does not discuss the new empirical findings related to the limitations of stage-based decision making. Practitioners who do not carefully read the entire 185-page document may not discover this crucial shift in NAEYC’s position.

Although stage theory can outline a rough idea about how young children develop, evidence does not support the use of developmental stages to frame what is appropriate to expect of typically developing children at different ages or to define rules of practice or standards for instruction.

Future Directions for Early Childhood Theory, Research, and Best Practice

To reiterate, educating young children is a complex and messy affair. Such an endeavor requires guiding theories that explain contradictory and multifaceted phenomena. One such theory was developed by Lev Vygotsky, a Russian educational psychologist (1897-1934). Vygotskian theory, also called sociocultural theory, has gained increasing popularity over the past three decades. Vygotskian theory agrees with the Piagetian belief that children construct knowledge from their environment rather than merely absorb it and that qualitative change is an important part of children’s development.

In sharp contrast, however, Vygotsky believed learning could lead development, rather than developmental attainment being a prerequisite for learning. Translating Vygotskian notions into developmentally appropriate terminology: DAP (for any age) are practices in which adults (or more skilled learners) provide experiences and help that allow learners to perform tasks and skills they would not be able to perform independently. These experiences further children’s development. Thus, sociocultural theory contrasts with the view that one must wait for development to unfold before teaching children more complex skills and that by merely providing an enriched physical environment children will spontaneously construct knowledge and acquire skill.

There are several other important ways in which socio-cultural theory differs from Piagetian theory that provide for richer, more complex conceptualizations of early childhood best practice. Piaget and Vygotsky’s theories were developed from very different theoretical questions. Whereas Piaget was interested in how children construct knowledge, Vygotsky was frustrated with the dichotomies between psychological theories. Vygotsky sought to unify dichotomies. Indeed he praised an American behaviorist, Thorndike, for his empirically sound and educationally practical descriptions of psychological theory. In his preface to the Russian translation of an educational psychology text written by Thorndike, Vygotsky says, “The most important feature of Thorndike’s book—its practical orientation . . . is evident from the structure of each sentence. It is wholly geared to practice, wholly created to meet the needs of the school” (Vygotsky, 1926/1997, p. 149). Yet Vygotsky also praised Piaget: “Psychology owes a great deal to Jean Piaget. It is not an exaggeration to say that he revolutionized the study of the child’s speech and thought” (Vygotsky, 1934/1986). A Vygotskian orientation can help researchers and practitioners step back from the DAP debate and consider how seemingly opposing ideas can explain how young children develop and learn. For example, Vygotskian practitioners do not ask if play or academic work is appropriate or inappropriate for young children. Rather, they ask how adults can support children’s play and academic work so that the activities promote learning and development (Bodrova & Leong, 2007; John-Steiner & Mahn, 1996).

Vygotsky’s theory also relies on a different developmental metaphor than Piaget’s stair-step maturation. For Vygotsky, development entails the passing on of cultural or cognitive tools. In the same way that physical tools help people master their physical environment, cognitive tools help people master their psychological or intellectual environment. Vygotsky believed that children developed by internalizing increasingly complex cognitive tools used by their culture. For example, contemporary cultures use traffic signs and rules to organize how vehicles and pedestrians travel. As children develop, adults help them learn these rules of the road so that they can get around safely. Similarly, young children learn counting (a cognitive tool) to master the quantitative aspects of their environment. They use this tool when they are told they may have two cookies or that three children may leave a kindergarten room to get a drink. As children develop, these tools facilitate their acquisition of even more complex tools (counting helps children later learn addition).

Vygotsky viewed development as adults turning over increasingly complex cognitive tools to young children through a process he called mediation. Mediation occurs within what Vygotsky called the zone of proximal development, or ZPD. The ZPD represents the developmental zone between what the child can do independently and the child’s maximum performance when provided with adult or peer assistance. For example, a 4-year-old child may not be able to count 20 objects independently, but with an adult holding her hand and counting with her, the child begins to coordinate all the necessary cognitive and fine motor movements to one day count independently.

Vygotskian practitioners do not ask if it is appropriate to teach 4-year-olds early literacy skills. Instead, if the skill represents a necessary cognitive tool, they develop ways to mediate the required tool within the child’s ZPD. Methods might include setting up print rich play areas (Morrow, 1991), engaging children in literacy events during dramatic play (Morrow & Schickedanz, 2006), helping children develop written plans that describe their play (Bodrova & Leong, 2007), and using direct instruction.

Because development is conceptualized as the mediation of culturally defined cognitive tools, culture is the central developmental consideration. Thus Vygotsky’s theory is compatible with culturally diverse child-rearing practices. Sociocultural practitioners do not categorize child-directed activities as appropriate and adult-directed activities as inappropriate. Rather they recognize that children need the ability to initiate and regulate self-selected activity and the ability to follow adult directives. Neither is inappropriate.

Piaget’s and Vygotsky’s theories also differ regarding the role of adults in children’s development. Piaget acknowledged the importance of social interactions, especially in regard to peer interactions in moral development. But he was much more concerned with children’s interactions with objects. Stressing the motivating nature of children’s curiosity, he encouraged the practice of letting young children freely explore environments enriched with interesting objects. With such exploration, cognitive development was assumed to spontaneously emerge. Thus, Piagetian practice promotes hands-off roles for parents and teachers in early learning experiences and especially in children’s play (Morrow & Schickedanz, 2006).

Vygotsky, however, differentiated between those cognitive skills that emerge spontaneously and those that require mediation by more competent members of the culture. He demonstrated that lower mental functions, such as reflexes or automatically attending to the source of a startling sound, emerge spontaneously but that higher mental functions, such as deliberate or focused attention, language, and logical reasoning, do not emerge spontaneously—rather they are mediated by more competent individuals. Therefore, interactions between mentors and children are crucial to development. From a sociocultural perspective, teachers and parents should actively engage young children in joint activity during which adults mediate important cognitive tools. In a Vygotskian frame, adults have significant and active roles in sociodramatic play (play in which children take on and act out imaginary adult roles and themes).

Sociocultural theory provides a unifying way to think about the major controversies affecting early childhood education. The theory provides a helpful way to frame research and practice regarding play and academics. Lesley Mandel Morrow has studied the effects of adults engaging preschool children in literacy activities during sociodramatic play. She and her colleagues found that children engage in literacy activities more often when adults help guide their play than when children simply play in print rich environments (Morrow & Schickedanz, 2006).

In another example of how Vygotskian theory can help early childhood best practice move past the DAP debate, early childhood researchers Elena Bodrova and Deborah Leong (2001) developed tools for teachers to use to scaffold young children’s acquisition of early literacy skills during sociodramatic play. In their program, teachers help kindergarten children develop play plans in which children describe their intended play activities. At first, children dictate plans to an adult who represents the child’s ideas in simple drawings and words. Then children draw their own pictures and dictate verbal descriptions to an adult scribe. In the final stage, children illustrate and write their own plans. Using play plans scaffolds children’s ability to mentally represent how they will play, to record those plans in print representations, and then to use those print representations to guide their play.

Bodrova and Leong (2001) compared urban kindergartens in their program with similar urban schools that used traditional methods. Children in the experimental schools demonstrated significantly stronger early literacy skills. Kindergarteners in the experimental program wrote more words, increased the complexity of their writing, and demonstrated more improvement in sound-symbol correspondence, better understanding of the concept of a sentence, better phonemic encoding of words, more consistent use of writing conventions, and more accurately spelled words. Their research and the work of other sociocultural researchers demonstrates the potential for sociocultural theory to resolve the theoretical and empirical difficulties faced by the early childhood field and yield a framework for reconceptualizing early childhood best practices.

Conclusion

In its advocacy for meaningful educational experiences for young children, NAEYC adopted a developmentally appropriate framework for identifying and describing early childhood best practice. NAEYC’s developmentally appropriate practice position statement has drawn both criticism and praise, prompting NAEYC to revise the position statement and attempt to clarify misunderstandings. Still, greater definitional, theoretical, and empirical clarification of early childhood best practice is needed. The early childhood field needs definitions of best practice that support complex understanding of how children learn and develop. There is a growing consensus that for young children those things academic are intrinsically embedded in relationships, imagination, and creativity. When a child climbs into a teacher’s lap to share a story or composes a make-believe shopping list, it is neither academic nor nonacademic. It is both, and more.

Recently, NAEYC leaders have moved the organization toward better definitions of early childhood best practice. Marilou Hyson, Associate Executive Director for Professional Development at NAEYC, recently highlighted changes in how NAEYC conceptualizes early childhood classrooms:

Our understanding of the place of academic content in the early childhood classroom has changed [since the 1980s]. Without a nurturing, playful, responsive environment, an academic focus may diminish children’s engagement and motivation. But a ‘child-centered’ environment that lacks intellectual challenges also falls short of what curious young learners deserve. (2003, p. 23)

Similarly, a 2003 NAEYC publication encourages “approaches that favor some type of systematic code instruction along with meaningful connected reading report children’s superior progress” (Neuman, Copple, & Bredekamp, 2003, p. 12).

These changes are encouraging. Still, if new conceptualizations about teaching young children are to significantly influence early childhood practice, changes must also be made in theoretical reasoning and terminology. Critical analysis of developmental theory requires differentiating between Piaget and Vygotsky. Such a differentiation allows the use of Piagetian theory to describe general patterns of cognitive development. Adopting a sociocultural model would allow early childhood best practice to move beyond dichotomies and to embrace culture as the central consideration in teaching young children. Sociocultural theory holds great promise for helping educators and researchers redefine early childhood best practice. Still, caution must be exercised as the field moves forward. No theory can adequately describe all aspects of how best to stimulate children’s growth. Wherever sociocultural theory fails to adequately inform early childhood practice, the theory must either be further developed, refined, or used in conjunction with other theories.

Moving past dichotomous thinking and embracing more complex theoretical models also requires a change in terminology. The language of a discipline defines the discipline (Vygotsky, 1926/1997). Attempting to define how young children should be taught through an appropriate versus inappropriate dichotomy fosters misunderstanding and inhibits rich, complex thinking. Adopting a best practice sociocultural model would allow the early childhood field to be shaped by a variety of valid and important perspectives.

See also:

Bibliography:

- Bergeron, B. S. (1990). What does the term whole language mean? Constructing a definition from the literature. Journal of Reading Behavior, 22, 301-329.

- Bodrova, E., & Leong, D. L. (2001). Tools of the mind: A case study of implementing the Vygotskian approach in American early childhood and primary classrooms. (Innodata Monographs 7). International Bureau of Education, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Bodrova, E., & Leong, D. L. (2007). Tools of the mind: The Vygotskian approach to early childhood education. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/Prentice Hall.

- Bredekamp, S. (Ed). (1987). Developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood programs serving children from birth through age 8: Expanded edition. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

- Bredekamp, S., & Copple, C. (Eds.). (1997). Developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood programs: Revised edition. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

- Delpit, L. D. (1988). The silenced dialogue: Power and pedagogy in educating other people’s children. Harvard Educational Review, 58, 280-298.

- Dickinson, D. K. (2002). Shifting images of developmentally appropriate practice as seen through different lenses. Educational Researcher, 31(1), 26-32.

- Goldstein, L. S., & Andrews, L. (2004). Best practices in a Hawaiian kindergarten: Making a case for Na honua mauli ola. hulili: Multidisciplinary research on Hawaiian well-being, 1, 133-146.

- Gutierrez, K. D., & Rogoff, B. (2003). Cultural ways of learning: Individual traits or repertoires of practice. Educational Researcher, 32, 19-25.

- Hyson, M. (2003). Putting early academics in their place. Educational Leadership, (60)7, 20-23.

- Jeynes, W. H., & Little, S. W. (2000). A meta-analysis of studies examining the effect of whole-language instruction on the literacy of low-SES students. The Elementary School Journal, 101, 21-33.

- John-Steiner, V., & Mahn, H. (1996). Sociocultural approaches to learning and development: A Vygotskian framework. Educational Psychologist, 31, 191-206.

- Kagan, S. L., & Lowenstein, A. E. (2004). School readiness and children’s play: Contemporary oxymoron or compatible option? In E. F. Zigler, D. G. Singer, & S. J. Bishop-Josef (Eds.), Children’s play: The roots of reading (pp. 59-76). Washington, DC: Zero to Three Press.

- Karp, N. (2006). Designing models of professional development at the local, state, and national levels. In M. Zaslow & I. Martinez-Beck (Eds.), Critical issues in early childhood professional development (pp. 225-230). Baltimore: Brookes.

- Kessler, S. A. (1991). Early childhood education as development: Critique of the metaphor. Early Education and Development, 2, 137-152.

- Lubeck, S. (1998). Is DAP for everyone? A response. Childhood Education, 74, 299-302.

- Morrow, L. M. (1991). Promoting literacy during play by designing early childhood classroom environments. The Reading Teacher, 44, 396-402.

- Morrow, L. M., & Schickedanz, J. A. (2006). The relationships between sociodramatic play and literacy development. In D. K. Dickenson & S. B. Neuman (Eds.), Handbook of early literacy research: Volume 2. New York: Guilford Press.

- Neuman, S. B., Copple, C., & Bredekamp, S. (2003) Learning to read and write: Developmentally appropriate practices for young. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

- Neuman, S. B., & Roskos, K. (2005). The state of state pre-kindergarten standards. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 20, 125-145.

- O’Brien, L. M. (1996). Turning my world upside down: How I learned to question developmentally appropriate practice. Childhood Education, 73, 100-103.

- Ormrod, J. E. (2008). Educational psychology: Developing learners (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

- Piaget, J. (1952). The origins of intelligence in children (M. Cook, Trans.). New York: Holt.

- Raines, S. C., & Johnston, J. M. (2003). Developmental appropriateness: New contexts and challenges. In J. P. Isenberg & M. R. Jalongo (Eds.), Major trends and issues in early childhood education: Challenges, controversies and insights (2nd ed.). New York: Teachers College Press.

- Skinner, B. F. (1984). The shame of American education. American Psychologist, 39, 947-954.

- Sousa, D. A. (2006). How the brain learns (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

- Stipek, D. (2006). No Child Left Behind comes to preschool. The Elementary School Journal, 106, 255-265.

- Van Horn, M. L., Karlin, E. O., Ramey, S. L., Aldridge, J., & Snyder, S. W. (2005). Effects of developmentally appropriate practices on children’s development: A review of research and discussion of methodological and analytic issues. The Elementary School Journal, 105, 325-351.

- Vygotsky, L. (1986). Thought and language (A. Kozulin, Trans.). Boston: The MIT Press. (Original work published 1934)

- Vygotsky, L. (1997). Preface to Thorndike. In R. W. Rieber & J. Wollock (Eds.), The collected works of L. S. Vygotsky: Volume 3: Problems of the theory and history of psychology (R. Van Der Veer, Trans.). New York: Plenum Press. (Original work published 1926)

- Zigler, E. F., Singer, D. G., & Bishop-Josef, S. J. (2004). Introduction. In E. F. Zigler, D. G. Singer, & S. J. Bishop-Josef (Eds.), Children’s play: The roots of reading (pp. 15-32). Washington, DC: Zero to Three Press.

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.