This sample Assisted Reproductive Technology ICSI Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Abstract

ICSI is the acronym indicating a new reproductive technique available since 1992, consisting in the injection of one sperm into one oocyte and subsequent transfer of the embryo in a woman’s womb. ICSI appears to be very efficient to overcome some kind of infertility and is a promising way to increase control over human reproduction. However, doubts and objections have been raised from both medical and religious quarters. Medical challenges had mostly been directed to the safety of ICSI, but most recent epidemiological research made clear that ICSI children are as healthy as sexually conceived children. Religious criticisms come mostly from the Roman Catholicism, which does not accept the separation between procreation and the conjugal act involved in any form of assisted reproduction. In ICSI such a separation is more neat and complete, and therefore, this technique is even worse than others. However, from a more general bioethical viewpoint, ICSI appears to be a new step forward for a better control of human reproduction which may open new frontiers for humankind.

Introduction

ICSI is the acronym for “intracytoplasmic sperm injection,” a particular practice of IVF (in vitro fertilization), i.e., general technique which allows for fertilization outside of a woman’s womb and takes place in a petri dish. Developed in 1978, IVF provided a tremendous impulse to various types of ART (assisted reproductive technology), which also includes simpler forms like the practice of in vivo insemination and donor insemination. From 1978 to 2013 more than five million people were born by means of IVF, ICSI, and other in vitro devices. These sophisticated techniques are still considered experimental today, but given these figures, it may soon become a routine treatment. In 2013 about 6 % of all newborns in Denmark came into the world through IVF (including ICSI), in the rest of Europe it was about 3–4 %, and in the USA it was about 1 %. For this reason, some scholars predict that in a few decades most of human reproduction in rich countries will occur with the assistance of technological devices.

Some Preliminary Conceptual Clarifications

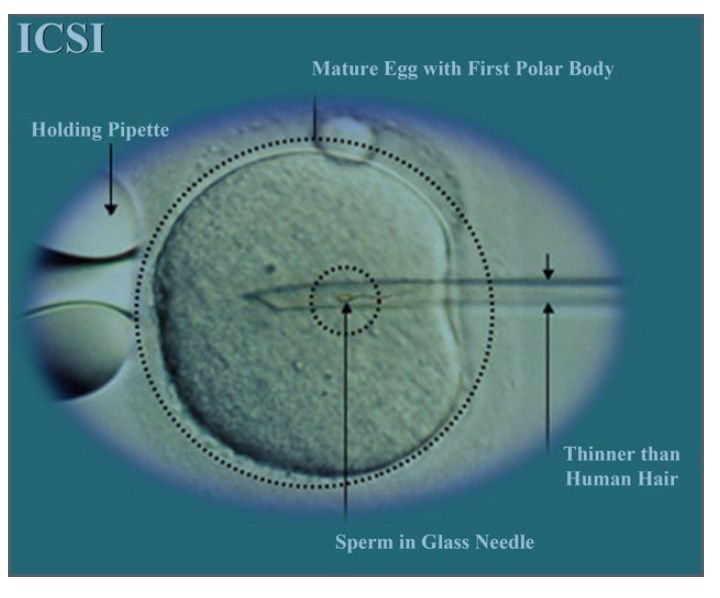

Properly speaking, in the most common form of IVF, many sperms are put in a Petri dish where fertilization occurs “naturally” in the sense that it is a chancy competition between at least 500,000 spermatozoa that decides which one will succeed in penetrating the egg’s membrane. Henceforth, “IVF” is used to refer to this specific process, which is different from the ICSI where the “natural” process of chancy competition is eliminated. In the ICSI, one single spermatozoon is selected and directly injected into a mature oocyte to induce fertilization, bypassing all other preliminary steps. Figure 1 shows the technique perhaps better than any presentation.

The ICSI was introduced in 1992 by an Italian gynecologist, Gianpiero Palermo, and it is very useful in overcoming male infertility (in cases of low sperm count) or when only a few oocytes are available. As a matter of fact, in a short time ICSI has become very efficient and it is now widely used in many fertility centers worldwide. Some believe that it is the predominant technique (about 70 % of all cycles), an aspect that shows its general impact on society at large. It is clear that a radical change in how people reproduce constitutes a historical leap which changes the basic parameters of our traditional settings. Until very recently, human reproduction was mostly left to a natural lottery, and now ART seems to allow for varying degrees of human control: lower in cases of in vivo inseminations, increasing with IVF where many spermatozoa are still in a natural competition, and reaching its peak with the ICSI, where gametes are selected by human choice. At the moment, this choice is based on mere biological criteria (motility, shape, etc.), but in the future even this aspect may change and become more sophisticated.

Figure 1. The A ICSI technique

Figure 1. The A ICSI technique

Since IVF still retains the aspect of “natural selection” among many male gametes, some think that it is better than the ICSI and that this latter technique should only be used in extreme cases. In this sense, these critics say that the rapid affirmation of the ICSI is not due to its superior efficiency, but to endogenous factors such as the psychological needs of the women who long for having an embryo transferred into their bodies and the advantages for the fertility center that would like to maintain a good reputation (Flamigni 2012, 2013). However, the ICSI appears to be used more than the IVF, even though the voices of its critics appear to be louder than those of its supporters.

The Ethical Controversies Surrounding The ICSI

Generally speaking, from an ethical point of view, ICSI appears to be a good practice, since it allows people to fulfill their life plans of having healthy children. In this sense it is beneficial both for the parents and for the child who can now enter into the world. This point is generally agreed upon not only by secular thinking but also by many religions for which ART, including ICSI, is the result of the effort instilled by God in humans in order to promote self-realization and happiness. From this viewpoint, at least prima facie, ICSI appears to be the latest step of a great leap forward for civilization, because it allows a stronger control on reproduction. However, there is no consensus on such a prima facie evaluation, and there are at least two major objections to the practice, which have to be examined. These objections are very different in structure and nature; they come from different fields of inquiry and point to different goals. In general, they express the same concerns that have been raised about all of these techniques since their earliest beginnings.

The first type of objection comes mainly from medical quarters and tries to consider how reliable ICSI and IVF are. Since ICSI is a technique which aims to produce living children, one problem is to establish if it is an effective method for achieving pregnancy. The best available records of assisted reproduction show that ICSI, as well as other techniques, is as efficient as the natural process. In this sense, they are a viable option for women who want to become pregnant. The remaining problem is to establish whether or not the children born through ICSI are as safe as children born after sexual or spontaneous conception.

One main area of concern is to establish if such techniques are, as such, risky or dangerous for the infant born through it, in the sense that they would be exposed to an increased risk of birth defects. If the techniques are not risky, then ICSI and IVF are dependable practices. If they are more risky, then it remains to be established how great the risk is before deciding whether or not they are acceptable. In any case, the question appears to be merely factual and far from containing any moral qualms. A closer analysis, however, reveals that the evaluation is implicit and hidden in the process: if a significant rise in the rate of birth defects would be recorded, then ICSI as well as IVF would not be as beneficial as was prima facie supposed and, therefore, would be morally defective.

After about five million infants born through ICSI and IVF, this criticism appears to be specious and somewhat arbitrary, at least prima facie. If such techniques were to be really risky or involved a visible and palpable danger, people would have perceived it by now and would have ceased to resort to it. The fast development of these techniques and the growing demand for them seem to confirm that the risk is not significant enough as to lead to the conclusion that ICSI is to be abandoned and banned: if the possibility of any harm would be perceived, people would prevent from resorting to it.

Nevertheless, at least the terms of the medical debate are to be presented and the alleged risks of genetic disorders which are supposedly connected to ICSI are to be examined. A preliminary problem is how to set the criterion, or the “meter,” required for comparing the real risks involved in ICSI. Since any birth is risky to some degree, this criterion is provided by the risk of spontaneously or sexually conceived birth (SCB). However, serious scientific research on the results of SCB has only been done since the 1980s, and the current dependable records are as follows: about 3 % of malformations at birth, plus about 3 % of mental retardation, to which one should add another 1 % of infants with Mendelian disorders and another 1 % of chromosomal disorder (this latter may increase up to 10 % depending on the age of the mother).

Roughly speaking, about 7 % of all infants resulting from SCB have birth defects upon coming into the world (at least in societies with an infant mortality rate of less than 1 %).

Granted such a basis and the fact that the consequences of technical intervention in reproduction which are related to growth may take years to become evident, many epidemiological studies have been done to examine the results of ICSI and IVF in order to ascertain if they are really more risky or dangerous. However, as Wen et al. (2012) made clear in an authoritative metaanalysis, most of them are not well designed; out of a list of 925 studies, 802 have been immediately excluded as unreliable and only 123 have been retrieved for more detailed evaluation. This further exam lead another 67 studies to be discarded, so that in the end only 56 (6.05 %) have been judged worthy of being considered. This illustrates how uncertain the empirical analysis of the problem is.

There is a second important conceptual difficulty concerning the comparison between SCB infants and ICSI and IVF infants. Parents who have children through SCB meet the requirement of so-called normality with regard to (young) age, fertility, and reproductive capacities. In contrast, however, many people resorting to IVF and ICSI obviously have serious reproductive problems: they are often older, subfertile, or having other pathologies. In this sense, the two groups are not homogeneous and it is difficult to state whether possible birth defects registered with ICSI or IVF infants are due to the technique itself or to other factors (age, infertility, etc.). At this point one can still hold that without such medical treatment, these parental factors would have prevented conception and no child with birth defects would have ever come into existence. However, it is one thing to say that birth defects are due to a medical technique in itself and another to say that they depend on the decision of parents with reproductive problems to have children.

If this distinction is taken for granted as a starting point of the argument and research, then we have to draw a distinction between two different situations: on the one hand there is the general comparison between IVF (including ICSI) infants and SCB infants, and on the other hand the comparison between IVF infants and ICSI infants.

As mentioned, the quality of most of the inquiries done so far is poor: our knowledge is provisional and more detailed research must be implemented.

An important and detailed study by Davies et al. (2012) compared an Australian cohort of 6,163 IVF/ICSI infants born from 1986 to 2002, of which 1,407 were ICSI, with SCB infants, and reached the conclusion that “the increased risk of birth defects associated with IVF was no longer significant after adjustment for parental factors.” This means that IVF is not more dangerous than SCB, if due distinctions are considered – such as the fact that many IVF pregnancies involve twins or triplets which may cause birth defects and other problems. In this sense, Davies reports that the general adjusted risk is 1.28 %, i.e., significantly higher than 1.0 % (the basic “natural” risk). However, among singleton IVF newborns from fresh embryos, the adjusted risk is 1.06, showing that IVF as such entails no increased overall risk for birth defects.

Davies’ report also compared IVF and ICSI infants and concluded that “the risk of birth defects associated with ICSI remained increased after multivariate adjustment, although the possibility of residual confounding cannot be excluded.” This conclusion was immediately amplified by the media all over the world and still serves as the base of many critics who say that ICSI is a serious danger for the newborn. Many ICSI parents were worried and many physicians had doubts about it. This is not the place to enter into a detailed analysis of such a conclusion, but it is important to say that this conclusion depends on the observation that among singleton newborns after ICSI with fresh embryos, the adjusted risk rose up to 1.55 %, i.e., 0.55 % above the 1.0 % threshold. This is a statistically significant increase, and Davies reported it correctly (mentioning the possibility of residual confounding). But in general terms, the number of ICSI infants with birth defects would only increase a few units. Moreover, that conclusion is criticized by Pinborg et al. (2012) on the ground of a recent study of a larger cohort of Swedish infants. This new study is based on 15,570

IVF/ICSI infants born between 2001 and 2007, of which 9,372 were born after ICSI. This new data appears to be more reliable than that deriving from the Australian cohort where most children were born when the ICSI was just beginning. In contrast to Davis’ conclusion, Pinborg’s result is that “the adjusted risk of birth defects for the ICSI vs. IVF cohort (2001–2007)” is 0.90 %, i.e., lower than the basic “natural risk.” This thesis is also confirmed by Wen et al. (2012), who remarked at the end of their meta-analysis that “there is no risk difference between children conceived by IVF and/or ICSI.” Finally, in a more recent study concerning newborns in the Nordic countries over the last two decades, Henningsen et al. (2015) register that the number of multiple births decreased with time as well as perinatal deaths and low birth weight. In brief, ART-conceived children are better off than those who are conceived naturally.

The aforementioned data seems to be the best that has been made available as of yet, and the situation it describes is not as discouraging as critics point out. However, even though some findings appear to be promising, empirical research on the issue is only just beginning and studies must be more refined. The controversy appears to be about facts, but sometimes one has the impression that there are so many variables to consider that in the end data is interpreted according to one’s world view. Those who think that nature is good and that assisted reproduction is violence against nature waiting to be vindicated tend to think that ICSI is dangerous or more dangerous than IVF. On the other hand, those who think that nature is not good and benevolent and that assisted reproduction is a support to people tend to hold that ICSI is not dangerous at all or perhaps even better than the natural process. For now we must wait for more reliable empirical data in order to see whether or not ICSI is really a safe technique. What is certain is that it is not grossly dangerous; this is demonstrated by the fact that people are generally happy with the results of assisted reproduction procedures.

There is a second major objection to ICSI that it is put forward by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith of the Roman Catholic Church. After having criticized the general practice of IVF in the Instruction Donum Vitae (1987), the Congregation returned to the issue in the more recent Instruction Dignitas Personae (2008), where the entire paragraph no. 17 is devoted to ICSI. The Congregation starts by acknowledging that “This technique is used with increasing frequency given its effectiveness in overcoming various forms of male infertility,” and in footnote immediately stresses that “there is ongoing discussion among specialists regarding the health risks which this method may pose for children conceived in this way”(Dignitas Personae 2008, footnote 33) – a topic that was already examined.

Apart from risks and other empirical data, ICSI is totally immoral for the Congregation on the grounds of principle, “Just as in general with in vitro fertilization, of which it is a variety, ICSI is intrinsically illicit: it causes a complete separation between procreation and the conjugal act.” In other words, ICSI is ethically wrong because it violates the moral principle of the inseparability of the unitive and procreative meanings of sexual intercourse. It is important to stress this aspect, since the passage goes on to say that

Indeed ICSI takes place “outside the bodies of the couple through actions of third parties whose competence and technical activity determine the success of the procedure. Such fertilization entrusts the life and identity of the embryo into the power of doctors and biologists and establishes the domination of technology over the origin and destiny of the human person. Such a relationship of domination is in itself contrary to the dignity and equality that must be common to parents and children. Conception in vitro is the result of the technical action which presides over fertilization. Such fertilization is neither in fact achieved nor positively willed as the expression and fruit of a specific act of the conjugal union.” (Dignitas Personae 2008, n. 17)

These words put emphasis on the effects of technical activity and may give the impression that once again the argument is framed in consequentialist terms. It is possible that this choice is based on the need to be easily understood by the audience. A large fraction of Western public opinion is very critical of the invasion of technology in human existence, and for these people such remarks may sound acceptable. However, most of the above reported passage of the Dignitatis Personae comes from the Donum Vitae, which is the Instruction that lays down the underlying principles prohibiting the ICSI. There we see that according to the Catholic view, the basic idea concerning human reproduction is that (A) “Human life is sacred because from its beginning it involves ‘the creative action of God’” (Donum Vitae 1987, n. 5). If the generation of the human person is the result of the technical action, and then (B) it “is objectively deprived of its proper perfection: namely, that of being the result and fruit of a conjugal act in which the spouses can become ‘cooperators with God for giving life to a new person.’ These reasons enable us to understand why the act of conjugal love is considered in the teaching of the Church as the only setting worthy of human procreation” (Donum Vitae, II, B, 5).

The moral prohibition of any technical intervention (ICSI included) in the natural process of the transmission of human life is justified by the idea that technology is not the appropriate way to cooperate with God and His “creative action.” As Pope Benedict XVI said on the 40th anniversary of the Humanae Vitae, “No mechanical technique can substitute the act of love that husband and wife exchange as the sign of a greater mystery which sees them playing the lead and sharing in creation” (Benedict XVI 2008). In this sense, the Roman Catholic argument is deontological, based on the principle that any direct interference with the conjugal act is a violation of “the power of the creative action of God” that we see “every time we witness its [of a life] beginnings” (Benedict XVI 2008) (Benedict XVI, On the 40th Anniversary).

Having clarified this point regarding the Roman Catholic doctrine, a further point is to ask why the ICSI, as well as other reproductive techniques, is not considered to be an efficient instrument developed by humans in order to cooperate with God in the generation of new persons. This is the solution envisioned by some other religions and also by some Christian churches: God endowed man with reason, and man used this faculty to develop assisted reproduction in order to fulfill the divine plans. Why is this line of thought excluded from the Roman Catholic doctrine?

There is no definite official answer to such questions, but three different answers can be detected:

(A) The first one appeals to the order of creation that for the Roman Catholic Church ought to be strictly respected when human reproduction is concerned. This is what underlies the passage of the Donum Vitae: “God, who is love and life, has inscribed in man and woman the vocation to share in a special way in his mystery of personal communion and in his work as Creator and Father” (Donum Vitae 1987, n. 3). The idea goes back to John XXIII’s encyclical Mater et Magistra (1961): “The transmission of human life is the result of a personal and conscious act, and, as such, is subject to the all-holy, inviolable and immutable laws of God, which no man may ignore or disobey. He is not therefore permitted to use certain ways and means which are allowable in the propagation of plant and animal life” (John XXIII (1961) n. 193).

(B) The second answer refers to the order of marriage and the family, i.e., the institutions devoted to regulating human reproduction. As Pope Paul VI wrote in the Humanae Vitae (1968),

Marriage is far from being the effect of chance or the result of the blind evolution of natural forces. It is in reality the wise and provident institution of God the Creator, whose purpose was to affect in man His loving design. As a consequence, husband and wife, through that mutual gift of themselves, which is specific and exclusive to them alone, develop that union of two persons in which they perfect one another, cooperating with God in the generation and rearing of new lives. (Paul VI 1968, n. 8)

(C) The third one is even more specific and points to an alleged order of the reproductive process that would permit God’s creative intervention. As Pope John Paul II said in his discourse of Sept. 17, 1983: “At the origin of each human person there is a creative act of God: no man comes into existence by chance; he is always the result of the creative love of God” (John Paul II 1983).

Interestingly enough, in this last quotation Pope John Paul II seems to say that what looks like biological randomness is in reality a way to realize a divine plan: so-called chance events are the longa manus through which God acts. It is also important to remember that that passage is reported also in footnote 18 of the Donum Vitae (Intro. n. 5) together with the Mater et Magistra, making it clear how the specific reproductive order is connected to the order of creation. Moreover, it explains another crucial idea held by Pope John Paul II, i.e., that since “the procreative capacity inscribed in human sexuality is – in its deepest truth – a cooperation with God’s creative power [.. .] man and woman are not the arbiters, are not the masters of this same capacity” but in it and through it they are called “to be participants in God’s creative decision.” Only God has “the power to decide in a final analysis the coming into existence of a human person” (John Paul II 1983). If man and woman had the control of reproduction, they would become “the ultimate depositaries of the source of human life” and cease to be “cooperators in God’s creative power” (John Paul II 1983). For this reason, ICSI and other forms of birth control are absolutely prohibited, and “to think or to say the contrary is equal to maintaining that in human life situations may arise in which it’s lawful not to recognize God as God” (John Paul II 1983).

The former remarks may explain why Roman Catholicism cannot accept the ICSI as well as other forms of assisted reproduction: the reason is that, far from being conceived as ways to cooperate with God’s creative action, they are seen as ways of attacking God’s sovereignty over part of the creation. In this sense, to hold that ICSI and the other forms of birth control are morally good seems to entail a kind of atheism or at least a proposal to change the concept of “God,” so that it no longer controls the transmission of human life. For this reason, ICSI is absolutely prohibited in Roman Catholic doctrine. In one sense it should be even worse than IVF and other forms of ART, because (as we have seen) in this one several hundred thousand spermatozoa “naturally” compete to get into the oocyte and nobody can predict which precise sperm will be successful. Therefore, there is still some space for events that appear to be chancy, but could also be seen as being caused by a providential order. On the other hand, in the case of the ICSI, even this little margin of randomness disappears.

Conclusion

Most of the medical debate is focused on the efficiency and security of the ICSI as compared with the IVF or the SCB. So far, ICSI appears to be a dependable technique that may turn out to be even better than “natural” conception. However, scientifically oriented empirical research is at its early stages and the situation may change in the future. Up to now, many aspects of the controversy surrounding the issue seem to be influenced by some more general “philosophical” premises which are mostly implicit. One of these concerns the gametes’ natural selection which is still present in the IVF, but not in the ICSI. At the moment, the spermatozoon’s choice is made based on rough criteria (morphological, motility, etc.), but in the future the criteria may become more refined. Some believe that this may contribute to opening new frontiers in human reproduction. Other believe that to cancel the basic randomness which allows for natural selection may endanger the health of future generations. It is difficult to say whether this concern has any scientific basis or is simply the secular cultural survivor of the old theological idea that chance is the shadow of providence, so that each human person is the result of a creative act by God.

Another implicit premise concerns different “philosophies of biology” concerning the earliest stages of the reproductive process. Some think that we should allow natural selection to choose the gametes because this is crucial for the newborn’s quality of life. Others remark that passage is not so important, as shown by the fact that so many early embryos are discarded even in the natural process (over 80 %). Regardless of how fertilization occurs, if an embryo survives the initial stages and pregnancy begins, this is an indication that it is good enough to develop into a viable newborn. In this sense, ICSI can be a perfectly reliable technique.

It seems likely that we will have to wait some decades before having an answer to the empirical questions that are at stake. In the meantime, the Roman Catholic moral theology can continue to stress that the ICSI is to be morally condemned and prohibited. We have tried to clarify the rationale of this negative judgment, which tends to be barely comprehensible to Western public opinion which is mostly in favor of the ART including the ICSI.

Bibliography :

- Benedict XVI. (2008). Address to the Participants in the International Congress organized by the Pontifical Lateran University on the 40th Anniversary of the Encyclical Humanae vitae, L’Osservatore Romano, 11 May 2008, 1. http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/ benedict_xvi/speeches/2008/may/documents/hf_ben-xvi_ spe_20080510_humanae-vitae_en.html. Last access on 15 Jan 2015.

- Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. (1987). Instruction Donum Vitae on respect for human life at its origins and for the dignity of procreation (22 February 1987): AAS, (1988), 70–102. http://www.vatican.va/roman_ curia/congregations/cfaith/documents/rc_con_cfaith_ doc_19870222_respect-for-human-life_en.html. Last access on 15 Jan 2015.

- Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. (2008). Instruction Dignitas Personae on certain bioethical questions, (8 September 2008) AAS, 100, 858–887. http://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/cfaith/ documents/rc_con_cfaith_doc_20081208_dignitas-perso nae_en.html. Last access on 15 Jan 2015.

- Davies, M. J., Moore, V. M., Willson, K. J., Van Essen, P., Priest, K., & Scott, H. (2012). Reproductive technologies and the risk of birth defects. New England Journal of Medicine, 366, 1803–1813.

- Flamigni, C. (2012). Marzo 2012. http://www. carloflamigni.it/scripta/bambini_nati_dalle_tecniche_ di_procreazione_assistita.html. Last access on 15 Jan 2015.

- Flamigni, C. (2013). Maggio 2013. http://www. carloflamigni.it/scripta/aggiornamento-bambini-natiprocreazione-assistita.html. Last access on 15 Jan 2015.

- Henningsen, A. A., Gissler, M., Skjaerven, R., Bergh, C., Tiitinen, A., Romundstad, L. B., Wennerholm, U. B., Lidegaard, O., Nyboe Andersen, A., Forman, J. L., & Pinborg, A. (2015). Trends in perinatal health after assisted reproduction: A Nordic study from the CoNARTaS group. Human Reproduction, 30, 710–716.

- John XXIII. (1961). Mater et Magistra. Encyclical of Pope John XXIII on Christianity and Social Progress. (May 15, 1961). http://w2.vatican.va/content/johnxxiii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_j-xxiii_enc_15051961_ mater.html. Last access on Jan 2015.

- John Paul II. (1983). Discourse to priests participating in a seminar on responsible procreation, 17 September 1983, Insegnamenti di Giovanni Paolo II, VI, 2, 562. http:// www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/speeches/1983/ september/documents/hf_jp-ii_spe_19830917_procreazioneresponsabile_it.html. There is an English translation at: http://www.fiamc.org/texts/christian-vocation-of-spousesmay-demand-even-heroism/. Last access on 15 Jan 2015.

- Wen, J., Jie, J., Chenyue, D., Juncheng, D., Yao, L., Yankai, X., Jiayin, L., & Zhibin, H. (2012). Birth defects in children conceived by in vitro fertilization and intracytoplasmic sperm injection: A meta-analysis. Fertility and Sterility, 97, 1331–1337.

- Paul VI. (1968). Humanae Vitae. Encyclical Letter of the Supreme Pontiff Paul VI on the Regulation of Birth. http://w2.vatican.va/content/paul-vi/en/encycli cals/documents/hf_p-vi_enc_25071968_humanae-vitae. html. Last access on Jan 2015.

- Pinborg, A., Loft, A., Aaris Henningsen, A.-K., & Ziebe, S. (2012). Does assisted reproductive treatment increase the risk of birth defects in the offspring? Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 91, 1245–1246.

- De Wert, G. (1998). Ethics of intracytoplasmic sperm injection: Proceed with care. Human Reproduction, 13(Suppl. 1), 219–227.

- Hoffman, B. (2003). Technological assessment of intracytoplasmic sperm injection: An analysis of the value context. Fertility and Sterility, 80, 930–935.

- Pollack, M. J. (2002). Intracytoplasmic sperm injection: A bioethical analysis. The Einstein Quarterly Journal of Biology and Medicine, 19, 13–19.

- Sànchez Abad, P. J., & Pastor Gracìa, L. M. (2005). La inyeccion intracitoplàsmatica de espermatozoides: Avance o imprudencia cientifica? Murcia (Espana): Editorial Fundaciòn Universitaria San Antonio.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.