This sample Child and Adolescent Mental Disorders Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Introduction

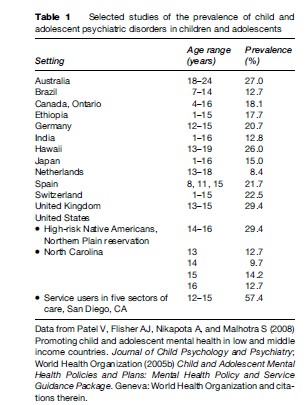

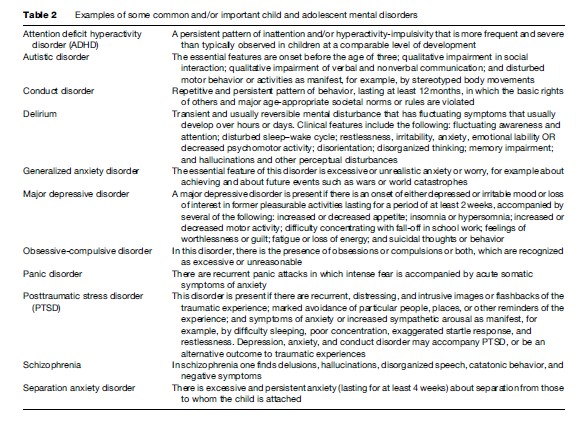

Reviews of the prevalence of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders indicate that about one in five children and adolescents suffer from such disorders (Table 1) some examples of which are provided in Table 2 (World Health Organization, 2005b; Patel et al., 2008 ). This estimate appears to be applicable to both genders, a range of ages within childhood and adolescence, all social classes, and both high-, low-, and middle-income countries. In this research paper, we have confined ourselves to psychiatric disorders in the narrow sense of the term. We have not addressed intellectual or learning disabilities.

Etiology

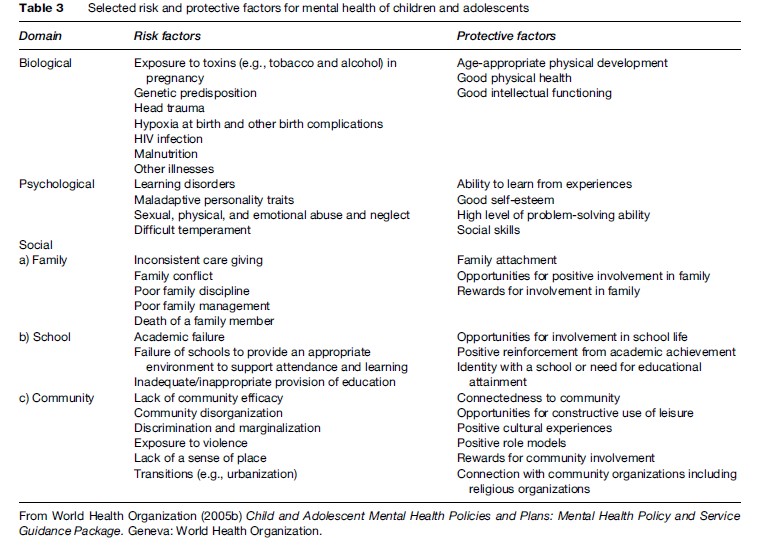

Whether a mental disorder develops in an individual and arises depends on the interplay between risk and protective factors. Risk factors are factors that increase the probability of developing a mental disorder, while protective factors moderate the effects of exposure to risk in the presence of one or more risk factors. For example, a person may have a strong family history of depression and thus be genetically predisposed to suffer from depression. Loss of a parent in adolescence may serve as another risk factor, which may then precipitate a major depressive episode. However, if such a person has strong connections with other family members, school, and community, such a depressive episode may be averted. In this case, the adolescent may experience a normal grieving process, which does not significantly adversely affect academic progress, relationships with peers, and physiological concomitants such as appetite disturbance and fatigue. This exemplifies the complex interaction of risk and protective factors at different ecological levels (Table 3) (World Health Organization, 2005b).

Public Health Significance

It is important to recognize that these disorders do not represent minor and transient responses to the normal challenges faced by children and adolescents. If this were the case, child and adolescent mental disorders would have limited public health significance. On the contrary, they are associated with a great degree of impairment and burden, longitudinal course into adulthood, long-term economic implications, associations with risk behavior, and stigma, each of which will be addressed below.

Impairment And Burden

The term impairment refers to interference with psychological or physical functions in one or more of the following domains: Interpersonal relationships, academic/work performance, social and leisure activities, and the ability to enjoy and obtain satisfaction from life. By definition, impairment always accompanies the presence of a psychiatric disorder, as impairment is a necessary condition for existence of a psychiatric disorder according to the diagnostic systems in common use. Indeed, if impairment is not included in the diagnostic criteria, the prevalence of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders in the general population would be two or three times the generally accepted prevalence. However, the extent of impairment varies according to diagnosis, with phobias being the least likely to be associated with impairment, followed by anxiety disorders and finally major depressive disorder and externalizing disorders such as conduct disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Furthermore, the extent of impairment is correlated with factors, independent of the nature of the psychiatric disorder. These include the extent of comorbidity, either a long or short duration of psychopathology, psychosocial adversity (in generalized anxiety disorder), and mothers’ ratings of the extent of conduct features (in children with conduct disorder).

Angold et al. (1998) reported that there is a positive association between impairment and parental perceived burden of care, although the direction of the causality has yet to be elucidated. The perceived burden of care was predicted by the child or adolescent’s total symptom score, the child or adolescent’s level of impairment, the presence of externalizing disorders (as opposed to internalizing disorders), and the existence of preexisting mental health problems on the part of the parent.

A further aspect of burden is the burden imposed by the disability suffered by the child or adolescent with a psychiatric disorder. This can be quantified by the disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) that are lost, which includes loss due to both mortality and disability, for each disorder. We do not have estimates of the DALYs lost due to child and adolescent psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence specifically. However, among 15–44-year-olds, we know that five of the ten leading causes of DALYs lost are psychiatric disorders (unipolar depressive disorders, alcohol use disorders, self-inflicted injuries, schizophrenia, and bipolar mood disorder) (Murray and Lopez, 1996). Furthermore, there is an important mental health or behavioral contribution to the etiology of a further three of the ten leading causes DALYs lost (HIV/AIDS, road-traffic accidents, and violence). It is probable that similar findings are applicable to childhood and adolescence. Such data have contributed to an increased appreciation of the public health importance of psychiatric disorders.

Longitudinal Course Of Mental Disorders In Childhood And Adolescence

There are two types of studies that address the longitudinal course of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders. First, there are studies that look back, by documenting the proportions of people with disorders in adulthood that had an age of onset in childhood or adolescence. The most sophisticated of these studies was conducted by Kessler et al. (2005). They reported that 75% of all adults with psychiatric disorder had an age of onset of 24 years or less, 50% had an age of onset of 14 years or less, and 25% had an age of onset of 7 years or less. For anxiety disorders, the corresponding ages were 21, 11, and 6 years or less.

Second, there are studies that look forward. There is good evidence of continuity of disorders that manifest themselves in childhood or adolescence into adulthood. In major depressive disorder, for example, depressed adolescents are at two to seven times increased odds of being depressed as adults. Furthermore, about one-third of children or adolescents with a major depressive disorder will later develop bipolar disorder, and this is more likely if there is a family history of bipolar disorder, psychotic symptoms, or a manic response to antidepressants. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder has three possible outcomes in adulthood, each of which occurs in about one-third of children with the disorder: (1) Developmental delay, in which over the course of time the individual no longer manifests impairing symptoms; (2) continual display, in which impairment related to ADHD persists into adulthood, although there are insufficient signs and symptoms for the diagnosis to be conferred; and (3) developmental decay, in which the diagnosis remains applicable in adulthood, often accompanied by other psychopathology such as substance abuse and personality disorder. Autistic disorder almost always is associated with lifelong impairment. However, there is considerable variation in outcome, with about 15% achieving independence in adulthood and a further 15–20% being able to function independently with periodic support.

In conclusion, there is evidence from retrospective and prospective studies of considerable continuity of psychiatric disorders from childhood to adulthood. This clearly provides support for increased resources to be allocated to child and adolescent psychiatric services, although evidence is currently sparse that early intervention will result in improved long-term prospects.

Long-Term Economic Implications Of Child And Adolescent Mental Disorders

Given the continuity of psychiatric disorders from childhood or adolescence into adulthood, one would expect that there would also be economic implications of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders that would persist into adulthood. Such economic costs can be direct or indirect. The former are generally easier to evaluate and reflect pharmaceutical costs, primary health-care costs, emergency department visits, and outpatient and inpatient care. The latter are generally more difficult to evaluate and reflect the caregiver costs, unemployment, decreased productivity, and increased demand on the education, social services, and criminal justice systems. Existing data on the long-term economic implications of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders are scanty and confined to the direct costs of a subset of disorders in the US and the UK (Romeo et al., 2005). However, the existing data confirm that the long-term costs associated with child and adolescent psychiatric disorders are large. For example, the treatment costs for youth with ADHD are approximately double those for youth without ADHD; the cumulative costs of public services utilized through to adulthood by individuals with antisocial behavior in childhood were ten times higher than for those with no antisocial behaviors by the age of 28 years, and the annualized cost in adulthood for those who suffered from both depression and conduct disorder was more than double that of the group with major depression alone (Romeo et al., 2005).

It can be seen that the potential economic impact of successfully implementing proven prevention and early intervention strategies for children with disruptive behavior disorders is enormous (World Health Organization, 2005b). The characteristically recurring nature of the mood disorders and the strong evidence for their continuity into adult life would seem to suggest an equally compelling argument for early intervention and even prevention in an effort to divert children from a possible trajectory of lifelong difficulties associated with substantial individual and societal costs.

Associations With Risk Behavior

There is robust international evidence that there is covariation between risk behaviors such as violent behavior, sexual behavior, suicidal behavior, dangerous roadrelated behavior, and use of tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs (Flisher et al., 2000). Furthermore, this cluster of risk behaviors appears to share common correlates, for example psychiatric disorder (Flisher et al., 2000). This has been established both for the cluster as a whole and individual components of the cluster. What is not clear is the direction of the causal relationship. Thus, the psychiatric disorder could cause the risk behavior or the risk behavior could cause the psychiatric disorder or they could both be caused by other factors. It is probable that the nature of the relationship varies according to the particular risk behaviors and psychiatric disorders in question. However, whatever the nature of the relationship, there are clear implications for public health. Specifically, preventive, promotive, or treatment interventions that address either risk behavior or psychiatric disorders would benefit from addressing the other aspect.

Stigma

The term stigma is derived from a Greek word and refers to a mark that denotes a shameful quality in the individual thus marked. It is a complex phenomenon that is modified by the culture and contexts in which it occurs. There are five interrelated processes that combine to create stigma: (1) people identify and label human characteristics, and differences that are regarded as relevant and consequential are determined; (2) stereotyping takes place in that the labeled person is associated with undesirable characteristics; (3) there is separation of the stigmatized group (them) from those who are stigmatizing (us); (4) the stigmatized group experiences discrimination and loss of status; and (5) the stigmatizing group exercises power. The association of mental illness with irrational, dangerous, and unpredictable behavior and the misconception that mental illness is not a true illness has resulted in those with psychiatric disorders being subject to stigmatization. Psychiatric patients and their families are doubly challenged: They are faced with the struggle caused by their impairment and they are confronted with chronic stress caused by the stigma that is associated with psychiatric disorders. As a result of these challenges, they are deprived of the opportunities such as good schooling and wide social networks, which in turn adversely affect self-esteem, and hence academic performance and economic well-being. Children and adolescents are particularly vulnerable to stigma for four main reasons (World Health Organization, 2005b):

- They are less likely to be able to advocate on their own behalf;

- Immature cognitive development results in children and adolescents being more likely to think dichotomously about opposites such as good and bad, and thus more likely to temper negative with other, less negative or positive, responses, and hence accept negative labels;

- The stigma suffered by children and adolescents may also affect the parents, which in turn could affect the quality of parenting that they are able to offer;

- There is limited understanding of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders, which implies that symptoms that are attributable to a psychiatric disorder may be attributed to other causes, such as passive aggression in the case of depression or overt oppositionality in the case of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; and their psychiatric disorders may persist into adulthood, which implies that any effects of stigma may persist for equally long.

Interventions For Child And Adolescent Mental Disorders

Mental Health Promotion

The aim of mental health promotion is to enhance positive mental health, which can be defined as the:

… capacity to achieve and maintain optimal psychological functioning and well-being. It is directly related to the level reached and competence reached and competence achieved in psychological and social functioning … Child and adolescent mental health includes a sense of identity and self-worth; sound family and peer relationships; an ability to be productive and to learn; and a capacity to use developmental challenges and cultural resources to maximize development (Department of Health, Republic of South Africa, 2003: 4).

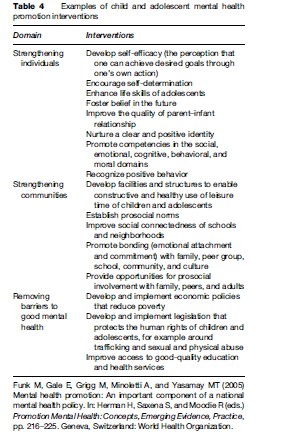

The focus is on enhancing protective factors through goals such as strengthening individuals, strengthening communities, and removing barriers to good mental health (Table 4) (Funk et al., 2005). What is the relevance of mental health promotion for child and adolescent mental disorders? The relevance is that mental health promotion interventions arguably also contribute to reducing the prevalence of child and adolescent mental disorders. However, the empirical justification for this statement is currently somewhat flimsy, partly because of the methodological challenges of demonstrating outcomes of upstream interventions (such as those mentioned above) on downstream outcomes such as specific disorders in specific individuals (Patel et al., 2008).

Mental Disorder Prevention

In contrast to mental health promotion, mental disorder prevention aims to reduce the prevalence of specific disorders, by focusing on risk factors. There are a number of interventions for specific disorders that have been shown to be effective, at least for populations in high-income countries. Examples of disorders and interventions that have been shown to be effective include (Durlak and Wells, 1997; World Health Organization, 2004):

- Alcohol misuse: School-based individual-level education and skills training combined with a mass media campaign, parent education and organization program, training community leaders and local policy changes;

- Anxiety: Teaching skills to manage anxiety symptoms more effectively;

- Conduct disorder: Child or adolescent behavior management, social skills for child or adolescent, multimodal school programs, and prenatal or early childhood programs;

- Depression: Improving cognitive and problem-solving skills, group interventions that focus on cognitive style and problem solving;

- Pathological eating behavior: Increasing self-esteem and improving general eating habits and behavior;

- Schizophrenia: Low-dose neuroleptic medication and cognitive behavior therapy;

- Suicide: School-based intervention with school suicide policy, teacher consultation and training, education to parents, stress management and life skills curriculum, and a crisis team.

Treatment

It is important to develop a comprehensive treatment plan for each child or adolescent and the family, which requires psychiatric services. This plan should:

- address each problem or disorder that was identified in the assessment;

- aim to modify all modifiable etiological factors in the biological, psychological, and social domains;

- involve both the family and the child or adolescent in treatment;

- include all contributory settings, especially the school;

- make use of the unique contributions of all appropriate members of the clinical team.

There is a rapidly expanding evidence base on the efficacy and effectiveness of interventions for child and adolescent mental disorders. Specifically, there is good evidence of the effectiveness of certain antidepressant and antipsychotic agents and of psychotherapy (especially behavioral and cognitive behavioral treatments for anxiety and mood disorders) (Evans et al., 2005).

The Current Response

We have argued above that the public health significance of child and adolescent mental disorders is enormous, and that there is evidence that preventive and treatment interventions (at least) can be effective. In light of these considerations, the response on the part of the health and other systems has been insufficient to meaningfully address the gap between the need for interventions and the available services. Only 7% of countries worldwide had a clearly articulated, stand-alone child and adolescent mental health policy (World Health Organization, 2005a). However, a larger proportion of countries have child and adolescent mental health content integrated into other policies, and/or have child and adolescent mental health programs. The proportions of counties with any child and adolescent mental health policy or programs are lowest in the Africa region, where 33% have the former (generally integrated into policy documents from other sectors such as child protection, social welfare, education, or human rights), while 6% have the latter (World Health Organization, 2005a). The corresponding figures for Europe are 96% and 67%. It is ironic that those countries with the largest proportion of children and adolescents are least likely to have a child and adolescent mental health policy. Other selected key aspects of the current situation include:

- There are no countries that have a data information system for child and adolescent mental health service outcomes at the national level.

- In the vast majority of countries outside of North America and Europe, systems for the care of children and adolescents with mental disorders do not exist, and when they do exist they are based in hospitals or custodial settings with minimal or no community-based services.

- Even when services are present, there are consider-able barriers to accessing it, such as stigma, lack of transportation, inability to pay for services, inability of the service providers to communicate effectively in the service users’ home language, and lack of public knowledge about mental disorders in children and adolescents.

- In countries in all economic categories, these services are generally paid for by temporary and vulnerable sources of funding such as the service user (or their family), nongovernmental organizations and international grants, as opposed to more stable government funding.

The Way Forward

The first step in responding to the scenario is to develop a child and adolescent mental health policy with an associated plan. The WHO has published a guideline on how to develop a child and adolescent mental health policy and plan (World Health Organization, 2005b), which provides a step-by-step approach that can be used by policy makers and planners. The steps for developing a policy are as follows: gather information and data for policy development; gather evidence for effective strategies; undertake consultation and negotiation; exchange with other countries; set out the vision, values, principles and objectives of the policy; determine the areas for action; and identify the roles and responsibilities of the various stakeholders. The steps for developing a plan are as follows: determine the strategies and time frames; set indicators and targets; determine the manor activities; and determine the costs, available resources and the budget. The plan should be backed up by sufficient resources and political will to ensure widespread implementation.

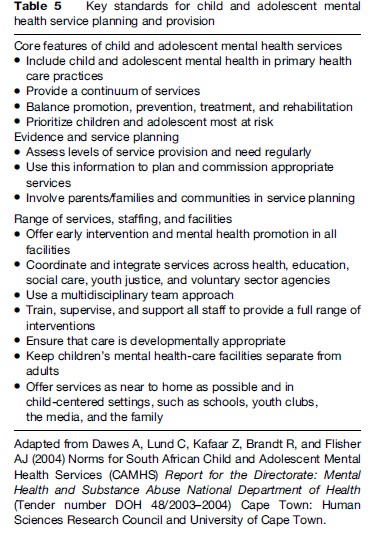

It is not appropriate to specify in detail the outcomes of the process of developing policies and plans for a country, province, region, or district. Indeed, as is obvious from the steps that have just been listed, this would contradict the letter and spirit of the guidelines. However, a broad consensus has emerged in recent years as to the key standards that should characterize a child and adolescent mental health service, whether in a high-, middle-, or low-income country, which are summarized in Table 5.

Conclusion

Far from being minor or transient variations in response to childhood adversity, or a medicalization of society’s intolerance of challenging childhood behaviors or inadequate parenting, it has become increasingly apparent that mental disorders presenting for the first time in childhood and adolescence represent serious conditions associated with markedly impaired functioning and significantly lower quality of life, for both the child or adolescent and their families. Even child or adolescent disorders traditionally viewed as mild, such as the anxiety disorders, are increasingly being construed as possible precursors of more serious and enduring mental health problems. In a substantial proportion of cases, psychiatric diagnosis in childhood or adolescence foreshadows psychiatric diagnosis in adulthood. An alternative view would suggest that child and adolescent psychiatric disorders provide us with a tantalizing window of opportunity for changing this gloomy trajectory. The exciting challenge for child mental health services is the prevention and early detection of these disorders; the implementation of evidence-based interventions with both short and long-term clinical and cost effectiveness; and the development of mental health systems that ensure equitable access to such interventions. We are in the earliest stages of meeting this challenge and exploiting this opportunity.

Bibliography:

- Angold A, Messer S, Stangl D, et al. (1998) Perceived parental burden and service use for child and adolescent psychiatric disorders. American Journal of Public Health 88: 75–80.

- Department of Health, Republic of South Africa (2003) National Policy Guidelines for Child and Adolescent Mental Health. Pretoria, South Africa: Department of Health Republic of South Africa.

- Dawes A, Lund C, Kafaar Z, Brandt R, and Flisher AJ (2004) Norms for South African Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) Report for the Directorate: Mental Health and Substance Abuse National Department of Health ( Tender number DOH 48/2003–2004) Cape Town, South Africa: Human Sciences Research Council and University of Cape Town.

- Durlak JA and Wells AM (1997) Primary preventive mental health programs for children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. American Journal of Community Psychology 17: 5–18.

- Evans DL, Foa EB Gur RE, et al. (eds.) (2005) Treating and Preventing Adolescent Mental Health Disorders: What We Know and What We Don’t Know. A Research Agenda for Improving the Mental Health of Our Youth. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Flisher AJ, Kramer RA, Hoven CW, et al. (2000) Risk behavior in a community sample of children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 39: 881–887.

- Funk M, Gale E, Grigg M, Minoletti A, and Yasamy MT (2005) Mental health promotion: An important component of a national mental health policy. In: Herrman H, Saxena S, and Moodie R (eds.) Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice, pp. 216–225. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Kessler R, Bergland R, Demler O, Jin R, and Walters EE (2005) Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distribution of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62: 593–602.

- Murray C and Lopez A (1996) The Global Burden of Disease. Boston, MA: Harvard School of Public Health WHO and World Bank.

- Patel V, Flisher AJ, Hetrick S, and McGorry P (2007) The mental health of young people: A global public health challenge. Lancet 369: 1302–1313.

- Patel V, Flisher AJ, Nikapota A, and Malhotra S (2008) Promoting child and adolescent mental health in low and middle income countries. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 49: 313–334.

- Romeo R, Byford S, and Knapp M (2005) Economic evaluations of child and adolescent mental health interventions: A systematic review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 46: 919–930.

- World Health Organization (2004) Prevention of Mental Disorders: Effective Interventions and Policy Options: Summary Report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (2005a) Atlas: Child and Adolescent Mental Health Resources: Global Concerns. Issues for the Future. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (2005b) Child and Adolescent Mental Health Policies and Plans: Mental Health Policy and Service Guidance Package. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Breinbauer C and Maddelino M (2005) Youth: Choices and Change: Promoting Healthy Behaviors in Adolescence. Washington, DC: PAHO.

- Kazdin A and Weisz J (2003) Evidence-Based Psychotherapies for Children and Adolescents. New York: Guildford Press.

- World Health Organization (2001) The World Health Report 2001: New Understanding, New Hope. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.