This sample Rural Health Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Introduction

Optimal health for individuals and populations, and the extent to which they need health care, results from the effects and interactions of many biological, environmental (both physical and social), and behavioral determinants, including the provision of appropriate health services. These determinants vary in their impact from one country to another and between population subgroups within these countries so that health status (based on measures of disease prevalence and incidence, mortality, morbidity, and life expectancy) is characterized by significant geographical variation. Most apparent at the international scale are the differences between less developed and developed countries.

At the same time, evidence suggests the existence of a substantial rural–urban health differential within countries at different points along this development continuum. In general, populations living in rural locations in most countries are characterized by poorer health status and the limited availability of, or access to, appropriate health-care services compared with urban dwellers. Rural populations generally can therefore be considered to be relatively ‘at risk’ in terms of their health and life chances.

This rural–urban health differential reflects in part the impact of specific rural environmental and locational factors upon health needs and access to health care and, more importantly, the ways in which broader structural and socioeconomic determinants of health affect rural populations (Marmot, 2005). These health determinants may be conceptualized as comprising ‘upstream’ factors (education, employment, income, living and working conditions), ‘midstream’ factors (health behaviors and psychosocial influences), and ‘downstream’ factors (physiological and biological causes).

This research paper highlights the differential in health status between rural and urban areas, outlines the nature of and interrelationships between factors responsible for this differential, and illustrates the problem across countries at different stages of development.

Defining ‘Rural’

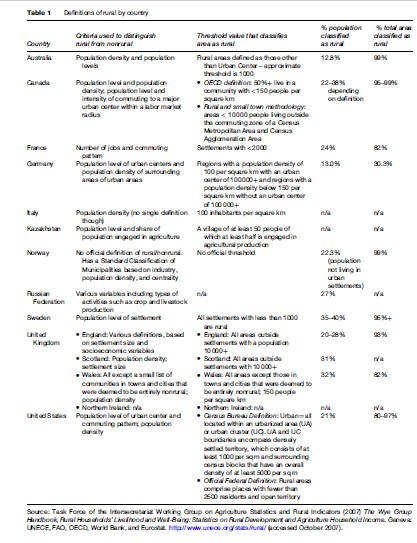

There is no universal agreement over the criteria by which rural is defined, nor any single, universally acceptable, all-purpose rural–urban classification (Humphreys, 1998). As a result, definitions of rural vary widely, as does the resulting proportion of population and land area classified as ‘rural,’ even between developed countries (see Table 1).

The concept of rural is complex, multidimensional, and often vague. Indeed, there is no point along the human settlement continuum where the urban disappears and rurality appears. Moreover, ‘rural’ areas across the world are characterized by considerable internal variability based on their diversity of residents, communities, environments, and accessibility.

Defining ‘rural’ has always been difficult. The effectiveness of such a definition depends on such factors as the specific purpose for which populations are being defined, the continual geographical changes resulting from ongoing social, economic, and technological developments, and the availability of data at a suitable scale to facilitate the precise delimitation of specifically ‘rural’ characteristics (Hart et al., 2005). The rural–urban distinction is most commonly based upon some combination of geographical criteria (including distance from urban centers, population size, and population density), social criteria (including culture, community attitudes, values, and lifestyles), and economic criteria (such as land-use type and intensity, occupational structures, and labor market context). In contrast to urban agglomerations, therefore, rural areas are usually characterized by small communities, and their populations are often widely dispersed and predominantly occupied in primary industries such as agriculture, fishing, forestry, and mining.

Rural–urban distinctions and the resulting rural–urban taxonomies are also commonly based on administrative boundaries that usually have little to do with health. In a rapidly changing and increasingly globalized society, some would therefore argue that the rural–urban distinction based on such delimitations is increasingly irrelevant. They point out that as a result of the intrusion and functional integration of urban influences within societies and their economies, the geographical distribution of social, economic, and environmental problems now tends to reflect structural processes operating at some broader national or international scale rather than being attributable to specific rural causes.

The absence of any consistent and comprehensive definition of rural means that direct cross-national comparisons of rural–urban ratios and any related rural–urban health differentials must be undertaken with some caution.

Rural In The World

Despite the considerable variation in definitions of rural, people living in rural locations are currently estimated to make up 51.3% of the world’s total population, the majority resident in middle or low-income countries. In 2005, an estimated 9.4% of all rural people lived in the most developed countries, such as France, the United States, Australia, and Japan; 73.8% in developing countries such as Brazil, Egypt, China, and Thailand; and 16.8% in the least-developed countries, such as Zambia, Tanzania, Bangladesh, and Indonesia.

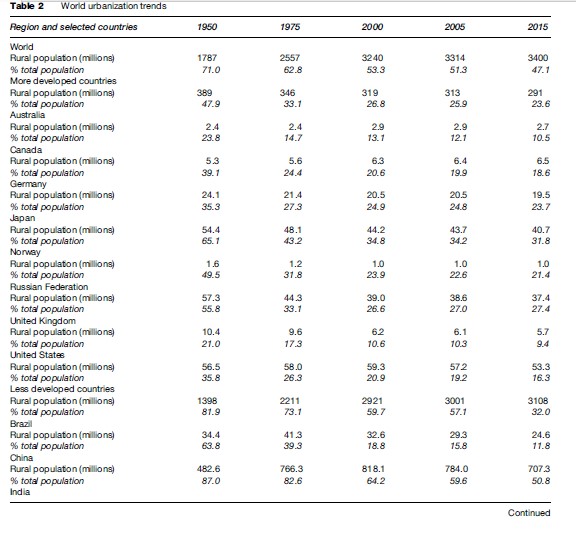

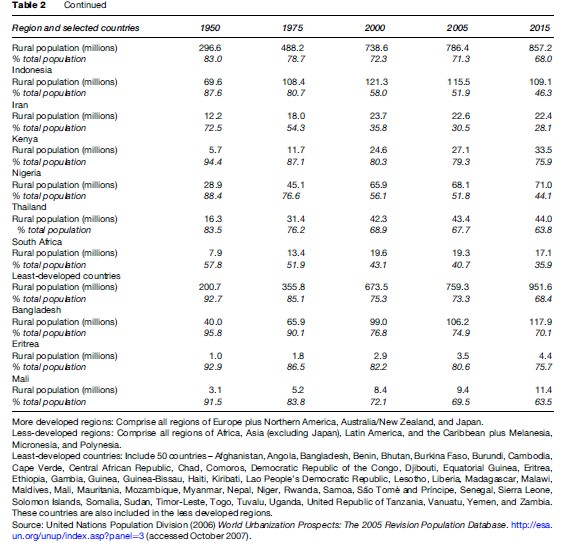

Secular trends since the mid-twentieth century show that the rural proportion of the global population has fallen substantially since the 1950s (see Table 2). This process of increasing urbanization is a function of both ‘push’ factors (escaping from adverse rural conditions characterized by population pressure, lack of employment opportunities, and environmental deterioration) and ‘pull’ factors (generally relating to the greater economic, social, and cultural opportunities in cities). Currently, the world’s urban-dwelling population is increasing at around 1 million per week. During this same period, however, as a consequence of dramatic population growth, the world’s total rural population has almost doubled in size to 3.3 billion people, largely in south Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

Although the percentage of the population defined as rural varies enormously between countries, there appears to be a close association with their stage of economic development. In general, the developing world (outside Latin America) remains much less urban than the developed world.

Underpinning these trends in the size and distribution of urban and rural populations in different regions of the world are changing patterns of fertility, mortality, and mobility. New pandemics and manmade disasters in the case of many of the least-developed countries are further complicating factors. Beneath these demographic processes are complex arrays of social, economic, and environmental factors that influence the individual’s exposure and response to various health-related conditions and that are played out in different ways in urban and rural locations.

Rural–Urban Health Differentials

That rural people are at greater risk of adverse health outcomes than their urban counterparts has long been supported by demographic and epidemiological data. As a consequence of their numbers, adverse social, economic, and environmental conditions, high exposure to biomedical and other risk factors, and suboptimal access to good quality health services, rural populations carry larger disease burdens than urban populations. Although such differentials have been consistently reported in both developed and less-developed countries, the size and nature of the disparities and their underlying determinants may vary in different rural environments.

Several different measures of health status have been used to identify and monitor rural–urban health differentials. Mortality rates are the most readily available measures of health status and heath need, and are often used to examine population trends and to compare the health status of different populations. These measures are particularly useful in countries with relatively high infant and child mortality rates and lower life expectancies and in which significant subpopulations, including those in rural areas, continue to be at higher risk for early mortality. Although this is more likely to be the case in developing than developed countries, there are some developed countries in which subpopulations such as indigenous and ethnic minorities continue to diverge significantly in life expectancy from the population at large. These high-risk groups are often concentrated in rural areas. These situations notwithstanding, it is true to say that as overall life expectancy improves, mortality may become a less sensitive measure of differentials between urban and rural populations.

Because mortality data reflect an ‘after-the-event’ situation they are less useful measures of the disease burden from chronic conditions that have long latency periods leading to death or that do not directly lead to death (for example, mental illness). With the increasing incidence of chronic disease in both developed and developing countries, the need to incorporate measures of nonfatal health outcomes has resulted in the development of summary measures of health gaps such as disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) that combines in one measure the time lost due to premature mortality and the time lived with disability. One DALY can be thought of as one lost year of ‘healthy’ life, and the burden of disease as a measurement of the gap between current health status and an ideal situation where everyone lives into old age free of disease and disability. While composite measures of this kind do provide a useful basis for comparing burdens of disease between different countries and populations they are seldom separately available for urban and rural populations. They are also seldom available in developing countries faced with logistic and resource constraints.

Comparisons of rural–urban differentials between high-, middle-, and low-income countries are inevitably complex. Depending on their political, social, and economic circumstances, these countries may be dealing with very different contributions to local burdens of disease. For example, the dominance of infectious, nutritional, and perinatal health conditions and new pandemics in less developed and developing countries contrasts with the dominance of chronic noncommunicable diseases in more developed countries. Moreover, different countries may be addressing these problems at different levels, with varying degrees of political will and with quite different social policies and economic resources (Raman Kutty, 2000). In short, while the trend toward growing urbanization is unmistakable in all countries, the nature and extent to which any substantial rural–urban differential is apparent may reflect the different health risks associated with stage of economic development as much as specific geographical differences.

Within any society the relationship between location and the pattern of health status remains complex because of the large array of intervening variables. Rural areas are generally characterized by different demography, lower income, education, and literacy levels, and poorer access to health care than metropolitan areas. In Australia, for example, 33 of the 37 poorest electorates fall within rural or remote areas, and access to health services remains problematic because of the long distances and the shortage of health workers in rural and remote areas. Even in Wales, a much more compact society, a substantial portion of the rural–urban mortality differential could be accounted for simply in terms of socioeconomic deprivation. In general, though, health data indicate that countries at equivalent stages of social and economic development are more likely to resemble one another in terms of rural–urban health differentials than countries at very different points along this continuum.

At the same time it should be noted that, historically, the current situation of rural health disadvantage has not always applied. For example, in preindustrial Europe and even the early decades of the Industrial Revolution in Europe, the risks of dying from contagious diseases during periods of epidemics were significantly less in rural areas than in cities. An equivalent situation pertains currently in many of the rapidly growing urban concentrations in developing countries, where recently arrived rural in-migrants live in large informal settlements with poor sanitation, overcrowded living conditions, and poor access to basic health and other services. The dynamics of these changing differentials in health status between rural and urban populations is illustrated in the following.

Urban–Rural Mortality Differentials In Brazil

Studies of infant and child mortality trends in the state of Sao Paulo in Brazil have shown a rapid decline in infant mortality rate from 100 per 1000 to 40 per 1000 between 1970 and 1998. During this period the greatest decline occurred in metropolitan Sao Paulo and, interestingly, in sparsely populated rural areas in the west of the state, while high mortality rates persisted in other rural areas. This reduction in mortality, which coincided with a period of economic downturn, has been ascribed to investment in water and sanitation infrastructure, a health clinic-building program, and concerted public health programs that included immunization, oral rehydration, and the promotion of breast feeding.

A more detailed analysis of under-5 mortality differentials by place of residence, wealth, and maternal education, however, demonstrated a much more complex picture. The outer metro fringe of Sao Paolo (the home to poor and socially disadvantaged rural in-migrants) had higher under-5 mortality than both metro core and rural areas in 1980. These city outskirts had limited public health facilities, infrastructure, or social support systems. By 1991, under-5 mortality in the outer metro had fallen below the levels for rural areas but was still significantly higher than the metro core. When under-5 mortality differentials were adjusted for household wealth, maternal education, and environmental conditions, the main determinant appeared to be social and economic disadvantage, both in the rural and urban areas.

Migration And The Spread Of HIV In Rural South Africa

South Africa is experiencing one of the fastest-growing HIV epidemics in the world. Thirty percent of all women attending antenatal clinics in 2005 tested positive for the HIV virus. Following steady and sustained reductions in infant mortality, fertility, and improvements in life expectancy between 1970 and 1992, infant and under-5 mortality rates have almost doubled in the last 10 years and the gap between rural and urban rates has widened. At the same time life expectancy has fallen by about 11 years.

Although the trend has affected the black population as a whole, the rural population has been significantly affected by the epidemic.

Circular labor migration between country and city is an established feature of rural community life in South Africa. This phenomenon is considered to have played an important part in the spread of the epidemic in rural areas. The role of migration in the spread of HIV to rural Africa has conventionally been seen as a function of men becoming infected while they are away from home and infecting their wives or regular partners when they return. However, the precise way in which migration contributes to the spread of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) in rural areas is complex and not well understood.

A recent study from South Africa showed that the prevalence of HIV among migrants and their partners was significantly higher than among nonmigrants and their partners. The fact that the odds of a migrant man being infected is 2.4 times the odds of a nonmigrant man highlights the importance of migration as one explanation of the size and rapidity of spread of the South African HIV epidemic, particularly in rural areas. Moreover, the study showed that migration is a risk factor not simply because men return home to infect their partners, but because their rural female partners are likely to become infected in the rural areas from outside their primary relationship.

Rural–Urban Health Differentials In Developing Countries

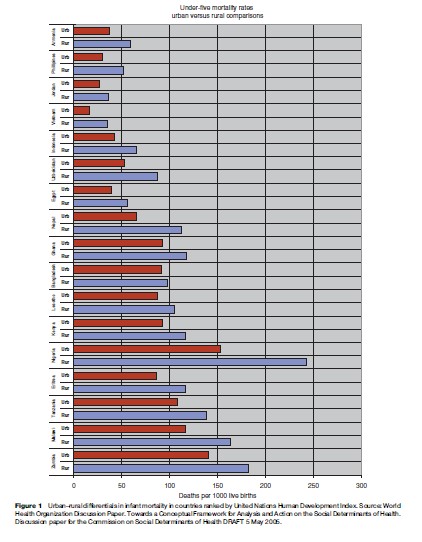

The contention that rural health status is worse than that of urban populations in developing countries is well supported by differences in rates of infant and child mortality, generally considered a good proxy for health status in these countries. Demographic and health surveys conducted between 2001 and 2005 in developing countries and ranked by the United Nations Human Development Index show that under-5 child mortality (a composite of infant and child mortality) is consistently worse in rural than urban households (see Figure 1).

Interestingly, this was a consistent finding irrespective of the country’s level of development or the stage it had reached in the health transition. Consistently worse rural infant and child mortality rates reflect some/all of such factors as poor social and environmental conditions, poverty, low levels of education, poor access to maternal and child health services, medical and public health care, and a lack of clean water and sanitation. These factors, characteristic of many rural areas, impact negatively on the health of rural communities. These comparisons highlight the clear survival advantage for urban populations.

It should be noted, too, that in many of the countries with lower under-5 mortality rates, this reduction has come, at least in part, as a consequence of the concerted implementation of child survival strategies and primary health-care systems in these countries over many years. Such strategies include growth monitoring, oral rehydration, breast feeding, immunization, female education, family spacing, and food supplementation. Limited as they may be in addressing more complex upstream determinants of disease, such strategies have nonetheless brought about a dramatic decrease in the incidence of vaccine-preventable diseases, diarrheal disease, and protein-energy malnutrition and have had a considerable impact on infant and child mortality, to which these conditions are major contributors.

Unfortunately, these effects have often occurred without parallel improvements in the structural and social determinants of health in rural communities. There is now a growing realization that further reductions in child mortality and sustainable improvement in the health status of rural communities will require more complex interventions and much greater attention to strategies that address the structural and social factors underpinning rural health status (Blakely et al., 2005). The recent emphasis on health disparities in developing countries is recognition of the fact that rural disadvantage, when more carefully examined, masks considerable differentials between subpopulations that carry larger or smaller burdens of disease in these communities. Programs to distinguish between populations in upper or lower quintiles based on social and economic indices are steps toward targeting subpopulations at special risk for poor health outcomes and at decreasing these health disparities and thereby further reducing mortality. These programs also recognize the large role played by social and economic conditions in determining health outcomes in all populations. In response to persistent health disparities, many middle and low-income countries have incorporated equity goals into their national public health programs. At a global level, initiatives such as the Global Equity Gauge have helped to develop and refine research methods to measure health disparities between different subpopulations and to address them through policies and programs that provide safety nets, increase resource allocation, and improve access to health services for populations at greatest risk.

Focusing attention on broad rural–urban differences, however, may hide the greater complexity characteristic of most developing countries. An understanding of these differentials and their underlying determinants is needed for more effective responses to health needs at a subregional level. Many developing countries, such as Brazil and South Africa, for example, are reporting changing burdens of disease that are less likely to be responsive to the ‘silver bullet’ interventions of the past 30 years.

The Brazilian case study discussed above demonstrates that mortality trends among children under 5 over a 25-year period have followed a pathway of improvement generated largely by the concerted implementation of standard child survival strategies complemented by environmental measures. While overall rural–urban mortality differentials have persisted during this period, the transition has masked fluctuations at the more micro level in the relative contribution to under-5 mortality by urban and rural subpopulations. It also demonstrates that, in the future, sustainable improvements in health status and elimination of health inequity will depend on addressing structural and intermediate determinants of health, such as economic and educational disadvantage, poor living and working conditions, food insecurity, and impaired access to health services (Sastry, 1997).

In contrast, in South Africa, the quadruple burden of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, the unfinished agenda of communicable and nutritional diseases, chronic noncommunicable diseases, and injury will require approaches specifically targeted at the health needs of rural communities. The success of strategies to prevent HIV infection, ameliorate its course in the already infected, and preempt its pervasive consequences for rural households requires a comprehensive understanding of the complex causal pathways that lead to HIV infection in many sub-Saharan rural communities (Lurie et al., 2003). The case study shows how rural health status and household dynamics and relationships at the micro scale reflect broader sociopolitical and macroeconomic forces and highlights the vulnerability of isolated and economically disempowered women in rural areas.

Rural–Urban Health Differentials In Developed Countries

Rural areas in developed countries are characterized by considerable diversity in terms of geography, culture, and economic activity. These significant variations in terms of population, population growth or decline, industry, socioeconomic factors, community resources, and ethnicity account for the lack of a clear-cut rural–urban health differential despite evidence of consistently higher health risk factors in most rural and remote areas, many of which increase with remoteness. The pattern of rural–urban variation in health status in developed countries also displays strong contrasts evident between geographically smaller, often more compact, and densely populated Western countries such as the United Kingdom and larger, more expansive, and more sparsely settled countries such as Canada and Australia.

Rurality or remoteness per se does not guarantee poorer health. Nonetheless, the role of rural location does appear to play a role in health disparities in large Western countries such as Australia, Canada, and the United States, where rural populations generally score worse on such general health indicators as mortality, life expectancy at birth and infant mortality, disease incidence, and hospitalization. In Australia, too, life expectancy varies with geographic location, with lower death rates for those living in capital cities compared to rural and remote areas. Rural residents also have more chronic health conditions such as diabetes, are less likely to receive preventative health-care services, and make fewer visits to health-care services.

In general the primary difference between the health of rural and urban residents appears to lie in the roles of specific health problems (such as suicide, most types of cancer, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and motor vehicle accidents) in which rural rates are elevated. The most striking difference between urban and rural in all causes of death is in trauma, with traffic accidents and suicides (particularly among men) claiming more lives in rural areas in Australia, Canada, England, the United States, and Wales. Rural residents also have higher mortality rates from stomach and lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, and various types of contamination and poisoning that have been linked to rural industries such as mining, agriculture, forestry, and fishing. The incidence of end-stage renal disease was also found to be higher in rural than in urban counties in one American study. Not all studies in developed countries show a rural disadvantage in health, however. Indeed, some studies in Canada and the United Kingdom have been less conclusive in identifying rural health disadvantage (Senior et al., 2000; Pampalon et al., 2006). For example, a Canadian study from the province of Quebec concluded that health status varies little between urban and rural residents, with similar life expectancy (despite higher infant mortality in rural areas). In other developed-world studies, breast cancer, ischemic heart disease, and hip fractures have all been shown to be lower in rural areas. Additionally, a Scottish study found a lower prevalence of asthma and some respiratory symptoms associated with living in a rural area. Research findings on general physical health (measured in terms of ‘self-assessed health’ or ‘functional ability’) vary, however, with some studies reporting higher urban morbidity and others higher rural morbidity. Similarly, the picture for respiratory problems is diffuse.

Clearly risk does not come solely from rurality. Rather, health disparities manifest in both rural and urban areas according to the role of health determinants. In the United States, for example, residents of inner-city areas and those living in rural areas experience similar health burdens, with higher mortality rates, poorer health, and greater likelihood of living in poverty than suburban populations. Studies in Scotland and Wales have demonstrated highest mortality in industrial and low-income areas in both urban and rural settings where socioeconomic and demographic determinants, rather than rurality itself, are the key influences on health status. Similarly, a Dutch study found that gender, marital status, and level of education were more important factors influencing physical health than urban or rural residence (Verheij, 1996). Likewise, studies of mental health undertaken in Finland, Sweden, the United States, New Zealand, and Australia all concluded that there was little evidence that ‘high-prevalence’ disorders were more common in urban residents once the effects of personal, social, and community factors were controlled for ( Judd et al., 2001). Again, then, other factors, such as poverty, unemployment, socioeconomic status, marital status, gender, and recent ‘life events’ were more powerful risk factors for mental health issues than urban/rural residence.

Australian and Canadian research suggests that diminished access to health services in rural areas contributes to rural–urban health differentials. Australian studies found that people living in rural and remote areas have a decreased chance of surviving cancer, partly due to poorer access to cancer treatment and support services in rural areas and to earlier detection, improved treatment, or both in urban areas. The role of geography is less apparent in the United Kingdom where, despite poorer access to services, levels of rural health are no worse than those in urban areas.

Rural populations in developed countries often contain subpopulations that are at especially high risk of poor health outcomes and that make disproportionate contribution to the high burdens of rural ill health. Particularly important in examining evidence of rural–urban health differentials in developed countries such as Australia and Canada is the high concentrations of indigenous populations in rural and remote areas, for this population group is known to have significantly worse health status (on all measures of mortality and morbidity) than that of the nonindigenous population (Adelson, 2005). Rural indigenous and some other ethnic minorities, characterized by the lowest socioeconomic status, are also particularly at risk in terms of their limited access to appropriate health care. This has specific implications for health policies and programs in these countries.

Explanations For The Health Status Of Rural Areas

Understanding the rural–urban health differentials noted in preceding sections requires accounting for their determinants – specifically, whether the nature of risk factors is the same between urban and rural areas in any society or whether their significance varies according to the stage of social and economic development and, if so, how. What is clear is that in any given geographical context, multiple determinants influence health outcomes and not all of them are simply attributable to geographical location (Dixon and Welch, 2000). For this reason, it follows that policy and program frameworks are needed that integrate these determinants and provide a more systemic basis for intervention at different levels within these causal pathways.

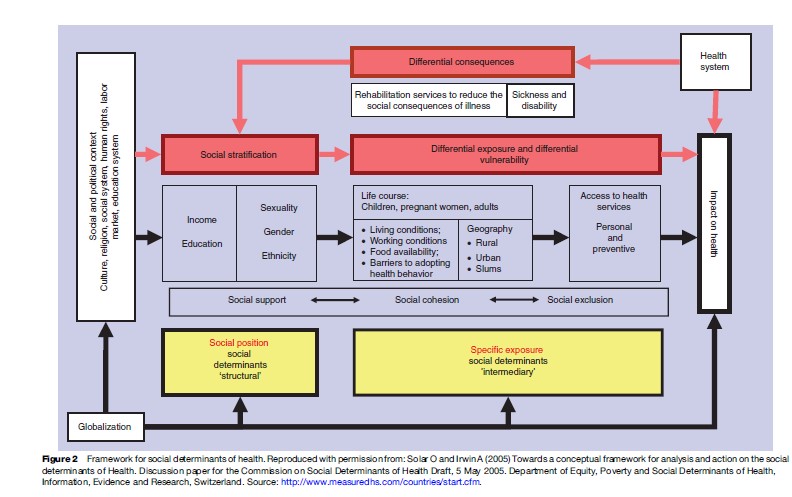

One such framework has been developed by the World Health Organization Commission on Social Determinants of Health (2005) (see Figure 2). This framework distinguishes between structural and intermediary determinants that have their main effects through upstream processes affecting social stratification and differential exposure to disease, respectively. While social stratification is determined by social and political forces such as culture, religion, education, and economic circumstances, exposure and increased vulnerability to health damaging conditions are more immediately determined by living and working conditions, availability and quality of food, supply of water and sanitation, and access to services. Although health systems have concentrated on interventions to address differences in exposure and vulnerability by providing equitable access to care, this model highlights the need for health systems to take responsibility for the promotion of intersectoral action in order to bring about any real improvement in population health status. Such an approach is integral to the World Health Organization Alma Ata concept of primary health care.

Interventions To Improve The Health Status Of Rural Populations

As we move along the continuum from less to more developed countries, health differentials are increasingly more likely to be effectively tackled through interventions addressing the social determinants of disease than by purely technical or biological interventions (Carr, 2004). In the least-developed countries (such as Bangladesh and Nigeria), infectious diseases, perinatal conditions, and nutritional diseases still predominate and are accompanied in most cases by large rural–urban differentials. These can be quite rapidly improved in the short term through quite simple and technical interventions addressing downstream biomedical determinants, such as immunization, oral rehydration, and vitamin A supplementation. In middle-income countries (such as South Africa and Brazil), populations continue to contend, in different measures, with mixed burdens of disease that include the unfinished agenda of infectious disease and perinatal conditions plus new epidemics of noncommunicable diseases and trauma. Further reduction in these burdens of disease that continue to be more acutely felt in rural areas will require interventions that address both downstream and upstream health determinants. Interventions, for example, to reduce or ameliorate the impact of developmental disabilities – a growing priority as child mortality falls – require strategies to reduce biomedical factors such as perinatal asphyxia while simultaneously addressing the need for psychosocial stimulation of young infants to improve intellectual and cognitive outcomes. In developed countries (such as Australia and Canada) facing problems of chronic and noncommunicable diseases, the case is compelling for interventions that tackle more upstream social determinants such as primary prevention strategies to decrease risk factors for coronary heart disease and interventions to decrease intentional self-harm in young rural men.

In addressing rural–urban health inequalities, important intervention choices will need to be made, including the number of points or levels of intervention, selection of target groups, and whether to focus attention more on disease-specific or upstream interventions. In many developing countries, district health systems based on primary health care already accept this combined responsibility for primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention. For example, attempts in South Africa to address the HIV epidemic demonstrate the utility of this kind of model in rural populations and the importance of multileveled interventions. A target group of special interest in tackling the epidemic has been pregnant women and young children, for whom primary prevention is now feasible through a set of strategies during pregnancy, labor, and infancy, including voluntary counseling and HIV testing, safe obstetric practices, antiretroviral therapy in pregnancy and following delivery, safe and protective sexual practices, and so on.

In contrast, while factors contributing to rural health disadvantage in developed countries include geographic isolation and problems of accessibility to health services, patterns of risky behaviors among rural people suggest a ‘rural culture’ health determinant. Elevated rates of smoking, lack of physical activity, and higher self-reported obesity characterize men and women in rural areas compared to nonrural. Recent evidence suggests that the health-care system makes a relatively small contribution to these health outcomes compared with a focus on modifying ‘upstream’ determinants such as income, education, and occupation disparities, and the impact of local community culture upon smoking, exercise, and nutrition behaviors of rural populations.

Prospects For Change In The Health Status Of Rural Areas

Since good health is a key determinant of life chances, rural residents exhibiting poor health status are likely to be significantly disadvantaged in their prospects and opportunities for social and economic well-being. For less developed and developing countries, in particular, without necessary economic and social development and improved health-care services, future prospects for millions of rural people throughout the world are grim.

The cost to the economies in these countries of avoidable burdens of disease is significant. For many predominantly rural developing countries, even in those with significant public health programs, the evidence indicates that attempts to improve the health of populations are producing mixed outcomes. For example, a study of immunization in India over the period 1993–99 showed that immunization achievements were worse in rural than urban areas, despite evidence showing some improvements in outreach at the national level. In other countries, intervention measures are not always targeting the level where the greatest health gains might obtain. In many countries, the bulk of public spending on health is still directed toward hospitals in urban areas and specialist care at the expense of rural primary care facilities.

A new commitment to identifying and tackling health disparities globally and the realization that economic and social conditions are very important determinants of these disparities are encouraging developments that could have positive outcomes for the health of rural populations. These are not easy interventions and will not produce results as quickly as the more technical biomedical approaches that have succeeded so dramatically for certain categories of health conditions in the past. They will require political will and a deep commitment to identifying and targeting populations at greatest risk for poor health outcomes, including rural subpopulations, with multileveled programs that address the many and complex determinants of disease in these communities.

Conclusion

In spite of difficulties in clearly defining rural communities and the relative dearth of good-quality data separately describing the health status of rural and urban populations, there appears to be ample evidence to support the claim that rural people experience health disadvantage when compared with their urban counterparts. This differential in health status is seen in both developing and developed countries, though the differentials appear to be wider in developing countries. Given the fact that rural people represent almost 50% of the world’s population, there can also be little doubt that programs to improve the health status of rural populations should be given greater priority in the global health agenda and should be given special attention in countries where these disparities are most evident. It is also clear that these geographical disparities may not in themselves provide a very good basis for action. They may mask the fact that this health disadvantage may be attributable to small subpopulations such as indigenous or ethnic minorities or that there are very specific environmental or occupational risk factors requiring quite specific and targeted programmatic responses. It may also not reveal without more detailed analysis that there are complex social and economic determinants of these health differentials requiring quite complex social interventions rather than health related programs.

Rural health disadvantage is in the end the expression of a complex array of underlying risk factors or determinants that are more prevalent or more prominent in rural areas. These determinants may differ from one population to another and must be carefully analyzed and understood to provide a rational basis for interventions that aim to improve the health status of rural populations.

Bibliography:

- Adelson N (2005) The embodiment of inequity: Health disparities in Aboriginal Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health 96: S2, S45–S61.

- Blakely T, Hales S, Kieft C, Wilson N, and Woodward A (2005) The global distribution of risk factors by poverty level. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 83(2): 118–126.

- Carr D (2004) Improving the health of the world’s poorest people. Health Bulletin 1. Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau.

- Commission on Social Determinants of Health (2005) Towards a Framework for Analysis and Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Commission on Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Dixon J and Welch N (2000) Researching the rural-metropolitan health differential using the ‘social determinants of health.’ Australian Journal of Rural Health 8: 254–260.

- Hart LG, Larson E, and Lishner DM (2005) Rural definitions for health policy and research. American Journal of Public Health 95(7): 1149–1155.

- Humphreys JS (1998) Delimiting ‘rural’: Implications of an agreed ‘rurality’ index for healthcare planning and resource allocation. Australian Journal of Rural Health 6: 212–216.

- Judd F, Jackson H, Komiti A, et al. (2001) High prevalence disorders in urban and rural communities. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 26: 104–113.

- Lurie MN, Williams BG, Zuma K, et al. (2003) Who infects whom? HIV-1 concordance and discordance among migrant and non-migrant couples in South Africa. AIDS 17: 2245–2252.

- Marmot M (2005) Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet 365: 1099–1104.

- Pampalon R, Martinez J, and Hamel D (2006) Does living in rural areas make a difference for health in Quebec? Health and Place 12: 421–435.

- Raman Kutty V (2000) Historical analysis of the development of health care facilities in Kerala State, India. Health Policy and Planning 15: 103–109.

- Sastry N (1997) What explains rural-urban differentials in child mortality in Brazil? Social Science and Medicine 44(7): 989–1002.

- Senior M, Williams H, and Higgs G (2000) Urban-rural mortality differentials: Controlling for material deprivation. Social Science and Medicine 51: 289–305.

- Solar O and Irwin A (2005) Towards a conceptual framework for analysis and action on the social determinants of Health. Discussion paper for the Commission on Social Determinants of Health Draft, 5 May 2005. Department of Equity, Poverty and Social Determinants of Health, Information, Evidence and Research. http://www.measuredhs.com/ countries/start.cfm.

- Verheij RA (1996) Explaining urban-rural variations in health: A review of interactions between individual and environment. Social Science and Medicine 42(6): 923–935.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.