This sample History of Leprosy Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Public health measures against leprosy have been influenced both by leprosy’s reputation and also by long-standing unsolved medical and scientific questions. Historically, Mycobacterium leprae has been a puzzling bacillus that has not been able to be cultivated in vitro. To make matters worse, over the ages leprosy has acquired a reputation as a ‘loathsome’ disease. While responses to leprosy vary across cultures and throughout history, in many instances, people have been required by law to surrender their liberty for their whole lives, for the sake of the health of the majority. Not until after World War II has effective medication been available for leprosy. In the absence of a cure, legislation to isolate and segregate those who suffered from the disease seemed to be the only way of containing it.

Origins Of Leprosy

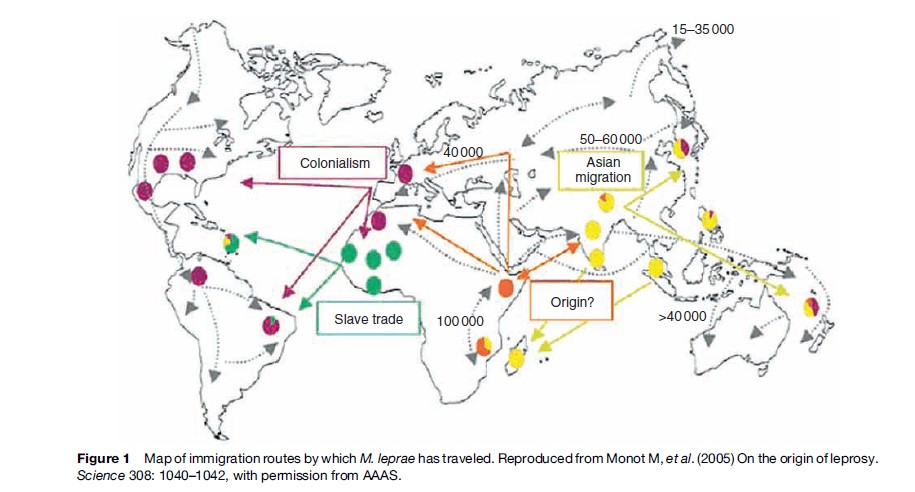

Until recent genome research, it was believed that leprosy originated in India and spread to Europe with the soldiers of Alexander the Great, who were returning from the Indian campaign, but recent genome research indicates that the disease has traveled with various waves of immigration, originating in East Africa. In the eighteenth century, for example, leprosy traveled with the slave trade to Central and South America (Monot et al., 2005) (Figure 1).

Leprosy In Early Sources

Leprosy In Ancient India

Ancient Hindu sources dating from 600 BC, the Charaka Samhita and the Sushruta Samhita, refer to leprosy under the names vata-rakta, vata-shonita, and kushtha. The Sanskrit word kustha refers to skin diseases in general. The disease was considered to be both hereditary and highly contagious, communicated through sexual intercourse, touch, breath, or sharing bedding or food. It was also believed to come about through divine retribution, and assisted suicide was a viable option for sufferers. Before the advent of the British in India, people affected with leprosy begged for alms and sought shelter in charitable establishments (Wilson, 1825; Dharmendra, 1940; Pandya, 2001).

Leprosy In Ancient China

In the nineteenth century, leprosy was associated with China and the Chinese, but the statistics for leprosy in China at that time have most probably been exaggerated (Gussow, 1989). Disease categories that include some of the characteristics of leprosy can be found in the Huang di Neijing, the earliest book of medicine in China (earlier than 200 BC). By the time of the Song dynasty (AD 960–1279) the present-day word for leprosy, mafeng, was in use. By the later Imperial period, probably as a result of confusion between leprosy and syphilis, leprosy became increasingly associated with ideas of moral contamination. When China became the People’s Republic of China, leprosy villages were established in all of the provinces and people were confined there and treated. Today China states that it has eliminated leprosy according to the terms of the World Health Organization (WHO) (for discussion of elimination of leprosy, see Leprosy).

Leprosy In Ancient Egypt

Palepathological evidence dating from the second century BC, in the Egyptian Dakhleh Oasis, shows changes in skeletal remains brought about by leprosy (Dzierzykray-Rogalski, 1980).

Biblical References To Leprosy

The stigma attached to leprosy has been attributed to the biblical proscriptions against the disease, including the requirement that anyone with the disease should be isolated from the community. The disease referred to by the Hebrew word za¯ra’ath (Leviticus 13 and 14), translated as leprosy, prescribes rituals for cleansing or purifying people, garments, and houses affected by the disease. Confusion arises because zara’ath, which should be translated to include any incurable, severe, or contagious disease, was translated into Greek as lepra. Lepra was then equated with leprosy in successive translations (Hebra and Kaposi, 1875; Lie, 1938).

Confusion In Greek And Arabic Medical Texts

Lepra in the Greek medical texts referred to a chronic, scaling, and harmless disease and elephantiasis to a chronic, nonscaling, and destructive disease that is recorded as making its appearance in Greece two centuries before Christ. An additional distinction needs to be made with the Arabic term djudzam that had also been translated as lepra, but in this instance it meant leprosy as we now know it. True leprosy was subsequently distinguished as Lepra Arabum – Elephantiasis Graecorum (Hebra and Kaposi, 1875).

Medieval Leprosy

In the nineteenth century, the medieval strictures against the disease were used to argue for the effectiveness of isolation, but this view is undergoing revision. There is no question that leprosy was present in medieval Europe, but the extent of this is unclear (Creighton, 1965; Gussow, 1989; Rawcliffe, 2006). The research of Møller-Christensen revealed skeletal remains bearing the effects of leprosy in four medieval Danish leper cemeteries, indicating the accuracy of the medieval diagnosis of lepromatous leprosy (Richards, 1977). Rawcliffe (2006) argues that the medieval lazarets offered a monastic refuge for those affected by leprosy, in keeping with what was considered an acceptable and praiseworthy way of life.

Leprosy In The New World

The ‘disappearance’ of leprosy from medieval Europe needs to be considered against the evidence of traces of the disease persisting in Europe in the Scandinavian countries, but also in Spain and Portugal, in addition to the growing presence of leprosy in the New World.

In the sixteenth century, both the Spanish and the Portuguese were aware of the need to make some provisions for leprosy in their colonial possessions, as well as at home. In Seville, Spain, for example, the San Lazaro Hospital, established in 1248 and still caring for patients until the 1930s, served as a prototype for the Spanish leprosy hospitals in the New World. In the Spanish those affected by leprosy. A Royal Commission was established and Dr. Jens Johan Hjørth (1798–1873), who surveyed leprosy in Norway in 1832 and traveled abroad to research the treatment of cutaneous diseases, made recommendations to the government for stemming the progress of leprosy.

Subsequently, leprosy control in Norway focused on a system of medical registration, legislation, hospitalization, and research. Surveys were conducted in 1836, 1845, and 1852, and a medical superintendent for leprosy, Ove Guldberg Høegh (1814–63), was appointed to be responsible for a national leprosy register, established in 1856. St. Jørgen’s Hospital and three additional hospitals, as well as a research hospital, were dedicated to leprosy, and the modern knowledge of leprosy entered a new era through the work of Daniel Cornelius Danielssen (1815–94), Carl Wilhelm Boe¨ck (1808–75), and Gerhard Henrik Armauer Hansen (1841–1912) (Figure 2).

Danielssen and Boeck produced what Ruldolf Virchow described as the beginning of biologic knowledge of leprosy. Their most notable publication was Om Spedalskhed published in Christiania, 1847, and translated into French as Traite de la Spedalskhed ou Elephanthiasis des Grecs (1848), possessions, leprosy hospitals were established on the and the Atlas Colori de Spedalskhed (Elephantiases des Grecs), island of Hispaniola (1520), and in Mexico City (1521); Lima (1563); Cartagena, Colombia (1592); Cuba (1617); Venezuela (1626); Argentina (1778); and in Louisiana, in the United States (1776), when it was a Spanish possession. Elsewhere, in the Philippines, 134 Japanese Christians with leprosy were exiled to Manila in 1632 and the Spanish established another San Lazaro Hospital outside the city of Manila in 1632, which was still operating at the beginning of the twentieth century (Toral and Dias, 1997; Gussow, 1989; Gould, 2005).

The Nineteenth Century

In the nineteenth century, complex debates about whether leprosy was contagious or hereditary were compounded by the relatively low communicability of the disease. Several questionnaire-based surveys, such as that conducted by Rudolph Vichow and that which resulted in the Report on Leprosy by the Royal College of Physicians in 1867, were carried out in an attempt to decide what to do about what was becoming an international threat (Gussow, 1989).

Norwegian Leprosy

In 1816 Johan Ernst Welhaven (1775–1828) exposed the shameful living conditions at the 400-year-old St. Jørgen’s Hospital for lepers in Bergen. He described it as a ‘graveyard for the living’ and 20 years later, the Bergen community petitioned parliament to build new nursing homes for which contained 24 lithographs by J. L. Losting (1810–76). The cause of leprosy was attributed to an inheritable dyscrasia of the blood, capable of latency, but emerging in unfavorable living conditions. They had not observed a single instance of the spread of leprosy by contagion in their vast experience at St. Jørgens and they strongly denied this possibility. If the disease was carried in a latent state by individuals, they should be stopped from reproducing, so sexual segregation was considered a necessity, and in 1850, the medical committee recommended that the marriage of leprosy-affected people and their children and grandchildren be prohibited.

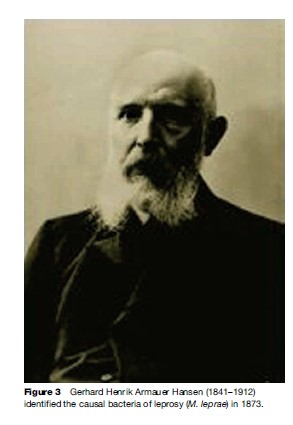

Gerhard Henrik Armauer Hansen (1841–1912) is credited with discovering that leprosy was a distinct, nosological entity. His identification of the bacillus M. leprae in 1873 was the first identification of a bacterium as the causative agent of a human disease. Legislation was introduced in Norway in 1877 and in 1885 required leprosy-affected people to be hospitalized. In a population of 1 500 000, 2858 people were diagnosed with leprosy in Norway and by 1906, there were 577. The diminution of the disease by the end of the nineteenth century became instrumental in convincing the rest of the world of the value of legislation and isolation measures along the lines of the Norwegian model (Richards, 1977; Irgens, 1984; Gussow, 1989; Andresen, 2004; Gould, 2005) (Figure 3).

Hawaii And Father Damien De Veuster

It was known that there was leprosy in Hawaii 40 years before the surgeon William Hillebrand, at Queen’s Hospital, Honolulu, reported on its rapid spread. This report, in 1863, provoked the Act to Prevent the Spread of Leprosy (1865). In the same year, land on the island of Molokai was purchased to receive the first contingent of leprosy-affected people on 6 January 1866. Between 1866 and 1905, 5800 people were sent to the settlements of Kalawao and Kalaupapa on Molokai, and only in 1969 did the legislation requiring involuntary lifetime isolation come to an end (Gussow, 1989).

In October 1863, the Belgian, Joseph de Veuster, was a last-minute replacement for his sick brother, Pamphile, to go to Hawaii as a Catholic missionary. Ten years later, as Father Damien, he volunteered to go to Kalawao, Molokai. He dedicated 16 years to improving the basic conditions of the colony and representing the needs of the people to the parsimonious Board of Health. He noticed the first signs of leprosy on his body in 1876. His death in April 1889 seemed to indicate conclusively that leprosy, as a germ disease, was communicable (Yzendoorn, 1927; Gould, 2005) (Figure 4).

Wellesley Bailey And The Mission To Lepers, India

In 1869, Wellesley Bailey, an Irish missionary with the Church of Scotland, became aware of the plight of people with leprosy in Ambala, India, in the Punjab. His letters inspired three Dublin friends, the Misses Pim, to organize small meetings to support him. The success of their appeals was the foundation for the Mission to Lepers in India, which established its own leprosy asylums and supported those of other missionary organizations. Today the Leprosy Mission still supports leprosy work throughout the world (Miller, 1965) (Figure 5).

The National Leprosy Fund And The Indian Leprosy Commission

The National Leprosy Fund, which had begun as the Committee for the Father Damien Memorial Fund, launched an investigation into leprosy in India. When the commissioners advised that leprosy was only mildly contagious, the Leprosy Fund overruled the commission and recommended segregation. In spite of this, the legislation in India was applied selectively by districts and only to pauper lepers (Kakar, 1996).

Berlin Conference, 1897

The first Leprosy Conference was held in Berlin in 1897, with 150 attendees, of which 44 delegates represented 22 governments. The gathering accepted that Bacillus leprae was the virus of leprosy. They concluded that in view of the virtual incurability of leprosy, the detrimental effects that it could cause to the community, and the reported good effects from the measures adopted in Norway, isolation was the best means of preventing the spread of the disease. They also appointed a commission to formulate a plan for an International Leprosy Society.

Leprosy In The Twentieth Century

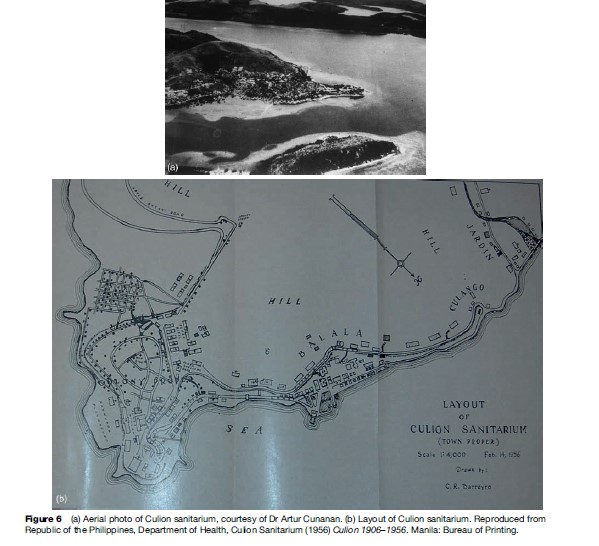

Leprosy was still present in the Iberian peninsula, the Mediterranean, the Balkans, and the Scandinavian and Baltic countries. Richards (1977) states that about 10 000 cases of leprosy were recorded in Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Iceland between 1856 and 1956. Legislation and leprosy institutions were introduced following the three congresses in Bergen (1909), Strasbourg (1923), and Cairo (1938). This was the period of the ‘model’ leprosy colony or settlement influenced by Molokai, Hawaii and the Culion Leper Colony, established in 1906 by the American government in the Philippines. The hospital and agricultural colony of Fontilles in Spain was established in 1907 (Bernabeu-Mestre and Ballester-Artigues, 2004); and, in the same year, after a leprosy survey that estimated that there were 30 359 people with the disease in the country, Japan introduced legislation aimed at pauper and vagrant lepers (Ohtani, 1998).

Bergen Conference, 1909

In 1909, Bergen hosted the second International Leprosy Conference, which affirmed the Berlin resolutions, and cautioned countries about the need for legislation to protect their borders. It also encouraged the search for a specific remedy (Currie, 1909).

United States National Leprosarium

The American Committee of the Leprosy Mission began in 1906 and was incorporated in 1917 as the American Mission to Lepers. In the same year, the United States enacted legislation to create a national leprosarium, and the asylum in Carville, Louisiana, to which leprosy-affected people had been sent since 1894, became the U.S. Marine Hospital, No. 66, of the Public Health Service in 1921 (Gussow, 1989; Gould, 2005).

Culion: The Model Colony

American dedication to leprosy in the Philippines intensified under the patronage of the new Governor-General Leonard Wood. By 1935, there were nearly 7000 people isolated on the island of Culion. When Wood died in 1927, the Leonard Wood Memorial Fund for the Eradication of Leprosy was incorporated in 1928 as a nonprofit organization in support of leprosy research (Long, 1967) (Figure 6).

Chaulmoogra Treatments

Until the 1940s, the only treatment believed to exert some beneficial effect was the oral use of the ancient Indian chaulmoogra and hydnocarpus oils, but they were so nauseating that patients generally were unable to take sufficient doses. Derivatives of Hydnocarpus wightiana and Hydnocarpus anthelmintica were developed either as ethyl esters or as sodium salts and administered by various methods of injection (Parascandola, 2003).

Third International Leprosy Conference, Strasbourg, 1923

Concerned that leprosy presented a threat through emigration from endemic countries, the third leprosy conference stopped short of introducing international legislation, but requested that the League of Nations constitute an international bureau of information and inquiry and collect statistics of leprosy throughout the world. It emphasized that isolation be humane but that indigent and homeless people be isolated and treated in a hospital, sanatorium, or agricultural colony.

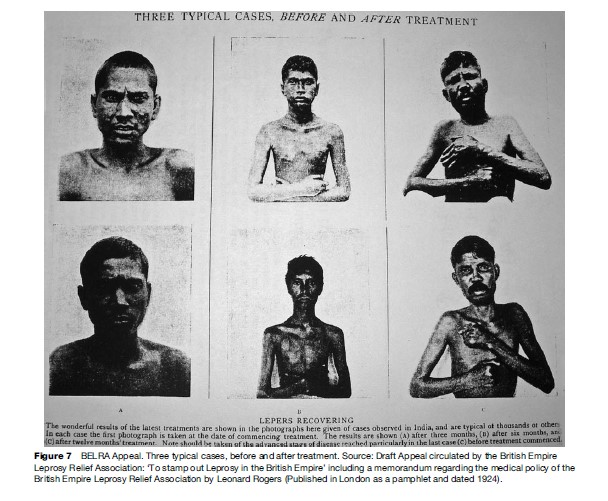

British Empire Leprosy Relief Association (BELRA)

The British Empire Leprosy Relief Association (BELRA) was formed in 1924 in a spirit of optimism prompted by the reported success in the use of sodium salts of hydnocarpus developed by Sir Leonard Rogers. BELRA estimated that there were more than ‘300 000 lepers in the Dominions of the King’ and stressed the importance of the detection and treatment of early cases and discouraged segregation (Stringer, 1974) (Figure 7).

League Of Nations Inquiry Into Leprosy

In response to the appeal made to the League of Nations at the Strasbourg Conference, the Health Committee of the League of Nations began an inquiry into leprosy in October 1925. Two meetings – one in Bangkok, in December 1930, and one in Manila, in January 1931 – set the groundwork for coordinating international research and epidemiological studies. In addition, the International Leprosy Association (ILA) and the International Journal of Leprosy were established. This new level of coordination culminated in the Fourth International Conference and First Leprosy Congress, in Cairo (21–27 March 1938).

The events of the 1930s gave rise to another spate of legislation and leprosaria construction. Japan revised its earlier legislation in 1931, and by 1941 succeeded in establishing 10 state-run sanatoria and isolating 11 383 people by 1943 (Ohtani, 1998) (Figure 8).

In Brazil, in 1929, there were an estimated 24 000 affected by leprosy and between 1930 and 1945, a nationwide network of leprosy colonies and preventorios were established. This network model was influential in China in 1957 (Figure 9).

Effective Chemotherapy: The Sulfones

In March 1941, Dr. Guy Faget, the medical officer at the U.S. Marine Hospital, No. 66, at Carville, Louisiana, performed a trial of promin, a derivative of the sulfone group, and found that it appeared to inhibit the progress of leprosy ‘in a considerable percentage of cases.’ Robert Cochrane was the first to use dapsone or diphenylsulphone (DDS), the parented forms in South India, and in 1948, small nontoxic doses of DDS by mouth were found to be effective. With this form of chemotherapy, ambulatory treatment by paramedical workers became possible. When effective medication became available, there were an estimated 10–12 million people suffering from leprosy worldwide (Stein, 1974; WHO, 2004; Gould, 2005).

The Gandhi Memorial Leprosy Foundation

Coinciding with the introduction of DDS in India and the birth of Indian independence, Indian indigenous activity against leprosy began with the establishment of the Gandhi Memorial Leprosy Foundation (GMLF). Inspired by Gandhi’s emphasis on leprosy as part of a program for national reconstruction, this organization began working with the government to launch the national leprosy program in India. India announced the elimination of leprosy by WHO standards in 2006.

Stanley Stein And The ‘Sixty-Six Star’

Leprosy-affected people did not suffer passively from the leprosy policies of the past. An outstanding example of resistance and militancy was initiated at Carville through the efforts of Stanley Stein (real name Sydney Maurice Levyson) who established the newsletter the ‘Sixty-Six Star’ on 16 May 1931. By 1933 the newspaper was crusading against compulsory segregation, the use of the word ‘leper’, and the relationship between leprosy and sin in the Bible. The newspaper stirred up so much controversy that it was forced to close in 1934, but began again in 1941 with the primary objective of educating the public about the disease. Increasingly, the people of Carville gained a voice for themselves, and in response to their interventions, in 1948, the Leprosy Congress in Havana banned the use of the word leper and called for the disease to be known clinically as Hansen’s disease (Stein, 1974).

Dapsone Resistance, Animal Laboratory Models, And Effective Chemotherapy

In 1960, Charles Shepard demonstrated that M. leprae from skin biopsy specimens could be grown in the footpads of mice. With an animal model, it then became possible to test the effectiveness of the available chemotherapy and thus perform trials of new drugs. Dapsone resistance (secondary) was conclusively reported in 1964, and in 1977, the long-anticipated and frightening prospect of primary dapsone resistance was recognized, thus it became vitally important to develop new and more effective chemotherapies. By 1984, the WHO was able to recommend multidrug therapy (MDT), which was a combination of clofazimine, rifampicin, and dapsone (WHO, 2004). The Nippon Foundation funded the supply of the WHO’s MDT worldwide from 1995–99 and now Novartis (a pharmaceutical company) provides supplies so that no person in need of treatment is denied it.

The Global Alliance For The Elimination Of Leprosy And The Integration Of Leprosy Into General Medical Health Services

In 1991, the World Health Assembly declared the goal to eliminate leprosy as a public health problem by the year 2000. The politics of this elimination strategy and the long-term consequences for leprosy have yet to be studied. Historically, the absence of a cure, as well as the opprobrium associated with leprosy, meant that for centuries leprosy was considered a disease ‘apart.’ Now with effective chemotherapy, and in the face of many other pressing diseases, leprosy should be confidently relegated to the status of any other disease – worthy of speedy diagnosis and effective treatment.

Compensation In Japan

On 11 May 2001, the government of Japan paid £10.4 million in compensation to 127 plaintiffs who had been unconstitutionally detained in leprosy sanatoria (Gould, 2005). The people of Taiwan and Korea are currently pursuing similar compensation.

The Genome

The whole sequence of the chromosome is now available. It is now possible to revisit some of the questions that have troubled leprosy research since the nineteenth century, and perhaps, before long, unravel some of the fundamental scientific questions associated with the disease (Colston, 2001).

The history of leprosy provides the opportunity to study social and cultural responses to a disease that, before effective medical treatment, often brought about a life sentence in isolation from society. The long-standing scientific difficulties associated with isolating the bacillus ‘in vitro’ and producing a laboratory model for the disease made it necessary for public health officials to seek other ways of dealing with leprosy. As a result, the affected person came to be equated with the disease, and the history of controlling leprosy became a history of controlling people, identified as ‘lepers,’ and viewed as a danger to the health of the population.

Simultaneously, equally long-standing medical uncertainties about contagion and the transmission of leprosy, even after the identification of the bacillus, left those who had contracted the disease open to suspicion. They were long judged to have done something immoral or ‘against nature’ to precipitate their illness. In spite of concerted efforts of medical education, this stigma has been difficult to disassociate from the disease. In the face of the widespread deprivation of liberty, legal rights, and personal identity, as well as the right to marry and bear children, leprosy-affected people have fought vigorously against stigma, especially the cruel designation of the term ‘leper’ so that they can be afforded the same rights as anyone else. In many countries, legislation is now in place that forbids the use of derogatory language to identify those who have suffered from leprosy.

This provides a unique example, in the history of public health, of society requiring the individual to sacrifice their interests for the ‘greater good.’

Bibliography:

- Andresen A (2004) ‘Patients for life’: Pleiestiftelsen Leprosy Hospital 1850s – 1920s. In: Andresen A, Gronlie T, and Skalevag SA (eds.) Hospitals, Patients and Medicine 1800–2000: Conference Proceedings, pp. 93–116. Bergen, Norway: Rokkansenteret

- Bernabeu-Mestre J and Ballester-Artigues T (2004) Disease as a metaphorical resource: The Fontilles philanthropic initiative in the fight against leprosy 1901–1932. Social History of Medicine 17(3): 409–421.

- Colston MJ (2001) The Mycobacterium leprae genome sequence: A landmark achievement. Leprosy Review 72(4): 385–386.

- Creighton C (1965) A History of Epidemics in Britain. London: Frank Cass.

- Currie DH (1909) The second international conference on leprosy, held in Bergen, Norway, August 1 to 19, 1909. Public Health Reports 24(38): 1357–1361.

- Dzierzykray-Rogalski T (1980) Paleopathology of the Ptolemaic inhabitants of Dakhleh Oasis (Egypt). Journal of Human Evolution 9: 71–74.

- Gould T (2005) Don’t Fence Me In: Leprosy in Modern Times. London: Bloomsbury.

- Gussow Z (1989) Leprosy, Racism and Public Health: Social Policy in Chronic Disease Control. San Francisco and London: Westview Press.

- Hebra F and Kaposi M (1875) On Diseases of the Skin, Including the Exanthemata, vol. 4. (trans. and ed.) Waren Tay. London: The New Sydenham Society.

- Irgens LM (1984) The discovery of Mycobacterium Leprae: a medical achievement in the light of evolving scientific methods. American Journal of Dermatopathology 6(4): 337–343.

- Kakar S (1996) Leprosy in British India, 1860–1940: colonial medicine and missionary medicine. Medical History 40: 215–230.

- Lie HP (1938) On leprosy in the Bible: part 1. Leprosy Review 9(1): 25–31 and part II Leprosy Review 9(2): 55–66.

- Long ER (1967) Forty Years of Leprosy Research: History of the Leonard Wood Memorial (American Leprosy Foundation) 1928 to 1967. Washington, DC: Office of the Medical Director, Leonard Wood Memorial.

- Miller AD (1965) An Inn Called Welcome: The Story of the Mission to Lepers 1874–1917. London: Mission to Lepers.

- Monot M, Honore´ N, Garnier T, et al. (2005) On the origin of leprosy. Science 308: 1040–1042.

- Ohtani F (1998) The Walls Crumble: The Emancipation of Person’s Affected by Hansen’s Disease in Japan. Tokyo: Tofu Kyokai Association.

- Parascandola J (2003) Chaulmoogra oil and the treatment of leprosy. Pharmacy in History 45: 47–57.

- Rawcliffe C (2006) Leprosy in Medieval England. London: Boydell and Brewer.

- Richards P (1977) The Medieval Leper. New York: Barnes and Noble.

- Stein S (1974) Alone No Longer. Carville, LA: The Star.

- Toral EM and Lopez Dias MT (1997) The influence of the San La´ zaro hospital of Seville in the creation and management techniques of the ‘lazaretto’ hospitals in the Americas. International Journal of Leprosy 65(2): 252–255.

- Wilson HH (1825) Kushta, or leprosy. Transactions of the Medical and Physical Society of Calcutta 1: 1–44.

- World Health Organisation (2004) Multidrug Therapy Against Leprosy: Development and Implementation over the Past Twenty-five Years. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

- Yzendoorn and Father R (1927) History of the Catholic Mission in the Hawaiian Islands. Honolulu: Honolulu Star-Bulletin.

- Brody SN (1974) The Disease of the Soul: Leprosy in Medieval Literature. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Carter HV (1874) Report on Leprosy and Leprosy Asylums in Norway with References to India. London: George Edward Eyre and William Spottiswoode.

- Edmond R (2006) Leprosy and Empire: a Medical and Cultural History. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Hansen G and Looft C (1895) Leprosy: In its Clinical and Pathological Aspects. Bristol, UK: John Wright.

- Kaplan DL (1993) Biblical leprosy: an anachronism whose time has come. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 28(3): 507–510.

- Newman G (1895) On the Decline and Final Extinction of Leprosy as an Endemic Disease in the British Islands. London: Royal Historical Society.

- Lloyd Davies M and Lloyd Davies TA (1989) Biblical leprosy: a comedy of errors. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 82: 622–623.

- Pandya SS (forthcoming) Ridding the empire of leprosy: Sir Leonard Rogers (1868–1962) and the oil of Chaulmoogra. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences.

- Pandya SS (2001) ‘‘Very savage rites’’: Suicide and the leprosy sufferer in nineteenth century India. Indian Journal of Leprosy 73: 27–38.

- Skinsnes OK and Chang PHC (1985) Understanding of leprosy in ancient China. International Journal of Leprosy 53(2): 289–307.

- Worboys M Was there a bacteriological revolution in late nineteenth century medicine? Biol and Biomed Sci 38(2): 20–42.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.