This sample Integrated Control of Tobacco Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

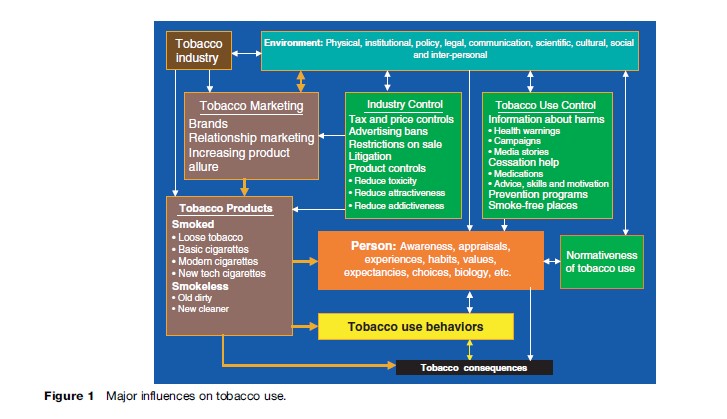

In February 2005, the World Health Organization’s first piece of international law, the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, came into force. This convention calls for, but only in some instances mandates, a broad range of actions that would, in total, represent an integrated approach to dealing with this major public health problem. The existence of the convention is the clearest possible manifestation of the realization that to effectively deal with a problem as complex as tobacco requires an integrated and comprehensive approach. Even though the first authoritative reports concluding that smoking is a major health hazard appeared in the early 1960s, little action to stem the epidemic occurred until the 1980s, and then only in a few countries. Unfortunately, until recently, there was little systematic effort to evaluate the actions that have been taken, and even less to explore possible interactive effects between government actions on the one hand and responses of the tobacco industry on the other. This research paper outlines actions that are being taken to reduce tobacco-related disease. A (… tobacco-related disease), organized around two main approaches, interventions focussing on tobacco use, and those focussing on the activities of the tobacco industry (Figure 1).

Tobacco Use Control

This has been the main focus of efforts to date. Here we include actions where the smoker or potential smoker is the direct target.

Ensuring An Informed Population

Strategies here range from mandated warning and product information on packaging, at point of sale, and in advertising (where it is allowed) to provision of information, largely through the mass media, in both paid and unpaid form.

There is now strong evidence that warning labels on packaging increase knowledge and stimulate quitting, although their net effect on cessation is probably small. The larger and more graphic the warnings, the better. Warnings with graphic photographs of smoking-related harms, first introduced in Canada in 2001, are the current state of the art in this area. Some jurisdictions (e.g., in Australia) mandate signs either warning of the harms or promoting Quitline services at point of sale, but the impact of these is unclear.

Ensuring that as much as possible of the scientific research on tobacco and its harms gets into the mass media is important. Research in the United States shows a strong link between the number of media stories and quitting-related activity. Similarly, well-constructed advertisements about the harms of smoking, and possibly about the devious behavior of tobacco companies, encourage smokers to seek help to quit, increase quit rates, and act to discourage youth from tobacco use. Part of the prevention effect seems to stem from disgust, rather than the anxiety that drives smokers. By contrast, outrage seems to be the mechanism when the focus is the behavior of tobacco companies. In the next few years there is likely to be increased international coordination of efforts to get important tobacco stories into the media, and continuing pressure for governments to continue to warn against the harms. Although most people have heard that tobacco is harmful, because it doesn’t seem harmful, the level of harm, and thus the need for action, is widely underestimated. Keeping the issue before the public and making the harms emotionally salient remain important strategies for discouraging use. There is also considerable evidence that mass-media campaigns are a particularly important strategy for less well educated populations, and provide one way to reduce the disparities in tobacco use across socioeconomic strata.

Smoking Cessation

There is now overwhelming evidence that a range of medications, including nicotine itself, aid in smoking cessation when used for periods of about 6 to 12 weeks. Other medications, including buproprion, work on aspects of the brain’s reward system. Advice-based programs increase in effectiveness with increased contacts (at least 4 to 8), with the best programs being at least as effective as medication. Even self-help booklets have a small positive effect. Advice-based programs are increasingly delivered by means of the telephone rather than face-to-face, and automated intelligence programs have also been shown to be effective. Combining advice-based programs with medication gives the best results, as the two seem to have largely independent effects. However, acceptance of help, particularly advice-based help, remains low, even when the help is subsidized or is free. This is probably due to a combination of beliefs, such as one ‘should be able to do it myself ’ and the deep ambivalence about change that characterizes tobacco use and other dependencies. As noted, promotion of the issue in the media drives people to seek help, as does product-specific advertising. Because smoking cessation involves a lifestyle change as well as overcoming a dependence, and because treatments lead only to short-to-medium-term behavior change, unless ex-smokers really come to value a smoke-free lifestyle they are likely to be at ongoing risk of relapse, even years after successfully quitting.

Prevention Of Tobacco Use

Programs targeted at preventing the uptake of tobacco use have generally not shown any marked long-term effects. The more effective programs seem to incorporate information about the harms (i.e., reasons for not smoking), understanding of dependence/addiction, skills training (especially refusal skills), and information countering the common misperception that more young people smoke than actually do. In recent years the tobacco industry has provided prevention programs in schools that notably deemphasize the health harms and focus on choices. There is concern that these programs are ineffective at best, and may encourage some tobacco use by helping frame tobacco use as a legitimate (thus sensible) choice. Many experts in the field believe that good public education plays a useful and probably necessary role, but unless accompanied by strong societal policies discouraging all harmful tobacco use (including among adults), it is unlikely to have much effect.

Smoke-Free Policies

One area in tobacco control where there has been major progress is in the move to smoke-free public places, motivated by the evidence on the harms of passive smoking, especially to nonsmokers. Wherever smoke-free public places have been mandated they have been complied with and supported by an overwhelming majority of the population, including, oddly enough, a majority of smokers. The most difficult places in which to prohibit smoking are bars and gambling venues. Even here, as demonstrated in Ireland in 2004, totally smoke-free pubs are not only achievable, but strongly supported by the community (Fong et al., 2006). Mandated smoke-free public places (including workplaces) lead to reduced cigarette consumption among continuing smokers, and a small increase in cessation (Borland and Davey, 2004). In addition, they seem to have a positive, albeit small, effect on people making their homes and apartments smoke-free, which in turn seems to aid in successful cessation. There is also some evidence that the existence of smoke-free public places inhibits the uptake of smoking.

Socioeconomic Differentials

In Western countries, and increasingly in developing countries, smoking is linked to social disadvantage. It is the educated and well-off who get the message and quit, and who protect their children from becoming smokers. Smoking rates are very high among the dispossessed within rich societies, and where they exist among ‘First Nation’ peoples. A major effort is required to address these inequalities as high smoking rates cause increased financial stress (due to the cost) and make a major contribution to the higher levels of ill health and premature mortality.

Controls On Marketing Of Tobacco Products

Tobacco is one of the first consumer products to be successfully mass marketed. Although some restrictions have been put in place, the tobacco industry continues to lead in the development of new marketing techniques, motivated, at least in part, by the constraints put on some of their strategies. Modern marketing is framed around the ‘four Ps’: Product, Promotion, Place, and Price. Tobacco control activities to date tend to focus on promotion and, through taxation, price.

Price

There is now compelling evidence that even though tobacco is addictive, its use is price sensitive. Increased prices (in real terms) increase cessation and reduce consumption. Price appears to have a stronger effect on uptake, at least in part because adolescents have less disposable income. Many governments around the world use tax on tobacco to raise revenue. In recent years, tobacco control advocates have pushed for tax increases as a means of controlling use. Tobacco taxes are one of the few popular taxes (even among smokers). However, rarely has a significant proportion of tobacco tax money been committed to programs to further reduce tobacco use – it appears that tobacco taxes are addictive to governments! In countries with strong tobacco control policies up to approximately 75% of the retail cost is made up of taxes. High taxes also have the effect of limiting tobacco companies’ flexibility to use price as a marketing tool, but in some countries this is complemented by price controls (e.g., minimum prices) to prevent discounting as a promotional tool.

Restrictions On Promotion

Efforts to restrict tobacco advertising have been a prominent part of tobacco control activities since the 1970s. Legislative bans, or other agreements to eliminate tobacco advertising on television, often lead the way. In many countries bans now extend to all electronic media, newspapers, and magazines and billboards. Increasingly, advertising is also being eliminated at point of sale. Reviews of the impact of such laws indicate that when they are relatively comprehensive they do reduce tobacco use, but if they are weak, tobacco companies can compensate by spending more on areas that are still allowed (Jha and Chaloupka, 1999). Several countries, including France and Thailand, now require cigarettes to be kept under the counter to eliminate the promotional aspect of large prominent cigarette displays. There is no good evidence on the impact of these laws.

In some countries all conventional advertising has been banned, including sponsorships of high-profile sporting and/or cultural events, but this does not mean that promotions have been eliminated. The essence of modern marketing is the brand, and tobacco products are all attractively branded. This results in smokers becoming unpaid brand promoters each time they publicly display the brand they are smoking. The other major promotional strategy is what is sometimes known as relationship, or ‘buzz,’ marketing. This involves building and helping to sustain a lifestyle in which the product, in this case, cigarettes, is designed to fit – just one of the things you do and have. There need be no mention of the product, so legislative controls are difficult if not impossible to maintain. A final challenge, and one that the parties to the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control are developing a protocol on, is cross-border advertising, which is occurring through satellite broadcasting and Internet communications. As long as tobacco companies make money from selling their products to consumers, they will find ways to promote them. Some people are now beginning to argue that the only way to effectively eliminate tobacco promotion is to remove the right of for-profit tobacco companies to market their products direct to consumers.

Places Of Sale

Tobacco remains one of the most readily available consumer products on the market. Many countries have prohibited sales to minors, and a few like France limit its sale to specialist retailers; however, in most countries, tobacco is still available in places where children buy sweets, and is often as cheap or cheaper than popular confections. Based on experience in restricting sale of other products, there is little doubt that reducing the number and type of outlets, and/or hours of purchase, would reduce consumption.

Product Regulation

Efforts to reduce the harmfulness of smoked tobacco products have not been successful. Industry obfuscation and misleading behavior coupled with official neglect has slowed understanding of this and has allowed an unacceptable situation to continue. Modern cigarettes are engineered to taste less harsh than the ‘gaspers’ of old. Consumers interpret this reduced averseness as evidence of reduced harmfulness, and are less concerned about smoking’s potential harms. The clearest example of this is so-called Light and Mild cigarettes, cigarettes designed to taste less harsh, and to appear to deliver lower levels of toxins. These cigarettes have filter ventilation, small holes in the paper around the filter, which allows air to mix with the smoke. The industry knew, what we know now, that smokers would compensate for this dilution effect: they block some of the holes and take larger and deeper puffs (which is easier to do with the cooler, more dilute smoke), ending up with similar levels of inhaled toxins and the same levels of disease (including new kinds of cancer deeper in the lungs). At the point of writing, no country has done anything more than ban the use of the misleading terms ‘mild’ and ‘light’ (the European Union first in 2003) and remove the misleading yield measures from packaging where they had been previously mandated (Australia first in 2006). There has been one other advance, legislating to reduce the propensity of cigarettes to start fires when left on potentially flammable surfaces (first in New York State, USA, then Canada). Discussion has begun about the legitimacy of additives and engineering features of cigarettes that effectively mask aspects of their inherent toxicity.

The tobacco industry has invested large amounts of money in attempting to develop less toxic cigarettes that are attractive to consumers. To date they have failed. It is becoming clear that combusted tobacco products are likely always to be extremely harmful, especially when the toxins are taken into the lungs. Some public health people and some tobacco companies are exploring the potential of smokeless tobacco as a harm reduction strategy. Sweden led the way in reducing the toxicity of smokeless tobacco (Snus in Swedish). Epidemiological research indicates that Snus and products like it cause no, or very little, cancer and overall is probably at least 90% less harmful than cigarettes (Foulds et al., 2003). One of the biggest questions in tobacco control is whether smokeless is part of the solution to smoked tobacco. It depends on whether smokers can be weaned on to the alternative product more quickly than getting them to quit altogether, on whether people will become dependent on smokeless tobacco, and on whether smokeless tobacco is sufficiently benign for long-term use.

As yet we do not have answers to these questions, although we know it is unlikely that we would want to have very large numbers of people dependent on smokeless tobacco. A related question is whether smokeless is a gateway to smoked tobacco. Research seems to be showing that it does not act in this way, but instead simply provides an alternative form of nicotine use (Ramstrom and Foulds, 2006). Overall, it appears that Sweden, where Snus has been popular for many years, is not doing any better in tobacco control than are some countries that do not have smokeless as an option. In Sweden Snus has not been used to systematically engineer a move away from smoked tobacco and most Swedish smokers still believe it is as harmful as cigarettes. The controversy over what, if any, role smokeless tobacco – or long-term recreational use of other cleaner forms of nicotine – might play in solving the tobacco problem is likely to continue.

Industry Illegality

In some legal circles there is a view that marketing tobacco itself, or at least some of the strategies used, might be construed as illegal, given that tobacco is harmful when used as intended, and given the appalling record of the industry in not unambiguously warning about those harms (Liberman and Clough, 2002). As a result there have been a number of successful prosecutions of tobacco companies, primarily in the United States. However, the deep pockets of tobacco companies and the complexities of the cases make this a difficult strategy. A lack of options short of eliminating tobacco use overnight, with the fears of the social dislocation prohibition might bring, is also inhibiting prosecution of the central illegalities. However, as alternative solutions to the tobacco problem begin to gain acceptance as viable, it may be that litigation rather than legislation will be the tool that brings about the major changes to the industry many believe are needed.

Conclusion

In summary, reducing the harm from use of a dependence-inducing substance that has been and in many ways still is deeply embedded in national cultures and economic activities, is a complex and difficult task. No single strategy has much potency in itself. The mix of strategies that have been used today has reduced the prevalence of cigarette use to less than 20% of the population in the most successful countries. To make further progress is likely to require greater application of the existing known strategies as well as new strategies based on a more fundamental appraisal of the role of the tobacco industry and the marketing of tobacco products.

Bibliography:

- Borland R and Davey C (2004) Impacts of smoke-free bans and restrictions. In: Boyle P, Gray N, Henningfield J, Seffrin J, and Zatonski W (eds.) Tobacco: Science, Policy and Public Health. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Fong GT, Hyland A, Borland R, et al. (2006) Reductions in tobacco smoke pollution and increases in support for smoke-free public places following the implementation of comprehensive smoke-free workplace legislation in the Republic of Ireland: Findings from the ITC Ireland/UK Survey. Tobacco Control 15(supplement III): iii51–iii58.

- Foulds J, Ramstrom L, Burke M, et al. (2003) Effects of smokeless tobacco (Snus) on smoking and public health in Sweden. Tobacco Control 12: 349–359.

- Jha P and Chaloupka FJ (1999) Curbing the Epidemic: Governments and the Economics of Tobacco Control. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Liberman J and Clough J (2002) Corporations that kill: The criminal liability of tobacco manufacturers. Criminal Law Journal 26: 223–236.

- Ramstrom L and Foulds J (2006) Role of Snus in initiation and cessation of tobacco use in Sweden. Tobacco Control 15: 210–214.

- Boyle P, Gray N, Henningfield J, Seffrin J, and Zatonski W (eds.) (2004) Tobacco: Science, Policy and Public Health. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Chapman S (2007) Public Health Advocacy and Tobacco Control: Making Smoking History. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- Ferrence R, Slade J, Room R, and Pope M (eds.) (2000) Nicotine and Public Health. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association.

- Jha P and Chaloupka FJ (1999) Curbing the Epidemic: Governments and the Economics of Tobacco Control. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- http://www.treatobacco.net – Database & Education Resource for Treatment of Tobacco Dependence.

- http://www.ntrjournal.org – Nicotine and Tobacco Research. Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco.

- http://tc.bmjjournals.com – Tobacco Control.

- http://www.surgeongeneral.gov – Reports of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- http://www.tobaccopedia.org – A source of lots of useful information.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.