This sample Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Introduction

Pregnancy and childbirth are among the most significant periods in women’s lives, both physically and emotionally. Women normally adapt to the physiological changes of pregnancy and are capable of delivering healthy babies with full recovery following delivery. However, some pregnancies may pose risks to the health of women and/or their babies, leading to unwanted consequences in varying severity – ranging from pelvic lacerations due to obstetric trauma to death. At an individual level, it is not usually predictable which women will experience either a minor or a life-threatening complication, although certain characteristics such as age, number of previous pregnancies and their outcomes, health status, and family history are associated with some of the negative outcomes.

At the population level, socioeconomically disadvantaged women are more likely to experience negative outcomes of pregnancy and childbirth. Substantial differences in terms of the type and extent of the complications exist between women living in more developed countries and those living in developing countries and among subgroups characterized by social, economic, geographical, and ethnic features within the same country. The reasons underlying these differences include physical vulnerability in terms of poor nutrition and lifestyle conditions, type of the health care available, and the extent of women’s receiving it, or, in most cases, a mixture of all.

The patterns of complications of pregnancy and child- birth reflect the capacity of the health system in a population, including the capacity of the health system to address the needs of the most vulnerable segments of the population. For example, hemorrhage is the most common direct cause of maternal deaths in most developing country settings, but few women die due to this condition in developed countries because it is preventable and treatable. So, both the prevalence of hemorrhage and the probability of dying from it are much lower in countries with more developed health systems. In this context, the main causes of maternal deaths are rare conditions that the medical profession is not able to prevent (such as preeclampsia) or treat (such as complications of congenital health disease) adequately. Understanding the causes of maternal deaths, the patterns of morbidities, the characteristics of the groups affected most, and health system failures is essential to determine where to concentrate efforts to provide improvements in a population. Such information is also an indicator of the broader issues of social inclusion, women’s status and rights, and socioeconomic development in the society.

Public health challenges remain at conceptual, measurement, and implementation (of effective interventions) levels, particularly in countries with less developed health systems. Developed countries are faced with a new challenge of sustaining the health system such that mortality and morbidity rates do not deteriorate as resources are shifted to other areas or training of health professionals ignores common problems.

Concepts And Definitions

Maternal Death

The World Health Organization (WHO) in the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) (1992) defines a maternal death as:

The death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management but not from accidental or incidental causes.

This definition allows examination of maternal deaths according to their causes as direct and indirect deaths. Direct obstetric deaths are those resulting from obstetric complications of the pregnant state (pregnancy, delivery, and the postpartum period) from interventions, omissions, incorrect treatment, or from a chain of events resulting from any of the above. Deaths due to hemorrhage, preeclampsia/eclampsia, or those due to complications of anesthesia or cesarean section are, for example, classified as direct obstetric deaths.

Indirect obstetric deaths are those resulting from previous existing disease or diseases that developed during pregnancy and were not due to direct obstetric causes, but were aggravated by physiologic effects of pregnancy. For example, deaths due to aggravation of an existing cardiac or renal disease are indirect obstetric deaths.

Accurate identification of the causes of maternal deaths to be able to understand the extent to which they are due to direct or indirect obstetric causes, or due to accidental or incidental events, is not always possible, particularly in settings where deliveries occur mostly at home and/or information registration systems are not adequate. In these instances, the classical ICD definition of maternal death will not be useful. A concept of pregnancy-related death included in ICD-10 incorporates maternal deaths due to any cause. With this concept, any death during pregnancy, childbirth, or the postpartum period is a maternal death even if it is due to accidental or incidental causes.

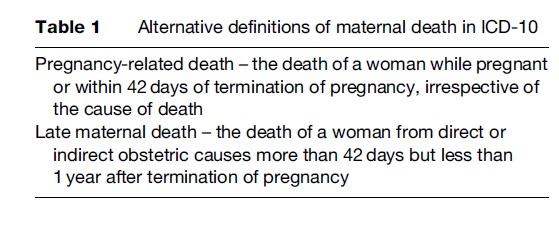

Complications of pregnancy or childbirth can lead to death after the postpartum period (42 days following delivery) has passed. Deaths due to aggravation of chronic conditions, such as cardiac diseases, may happen at a relatively late stage. In addition, increasingly available modern life-sustaining procedures and technologies help more women survive adverse outcomes, but may also delay death. Despite having been caused by pregnancy-related events, these deaths do not appear as maternal deaths in registration systems that use only the conventional definition. An alternative concept of late maternal death is included in ICD-10 to capture delayed deaths (those due to the complications of pregnancy and childbirth that occur later than the completion of 42 days after termination of pregnancy up to one year) (Table 1).

These alternative definitions, particularly the concept of pregnancy-related death, allow identification and measurement of maternal deaths in settings where accurate causes of deaths are not known by means of reliable information registration systems. In these instances, determination of maternal mortality levels mostly depend on ad hoc household surveys, where relatives of a woman who has died at reproductive age are asked about her pregnancy status at the time of the death. In settings where established routine registration systems with correct attribution of causes of death exist, it is possible to identify maternal deaths that fit into the classical ICD definition of maternal death.

Maternal Morbidity

Defining morbidity as an outcome is more difficult than defining death in general. Conceptualization of maternal or obstetric morbidity is particularly difficult as compared to defining morbidities in other areas of medicine because of the wide range of pregnancy outcomes, each with varying severity. Definitions of specific negative outcomes differ in different settings or for different purposes. For example, severe postpartum hemorrhage, one of the main causes of maternal deaths, is defined as blood loss greater than 500, 1000, or 1500 ml in different settings. One reason for this is that the amount of blood loss that could lead to death would differ according to a woman’s preexisting health, in particular her hemoglobin status, or her probability of receiving timely and adequate care. An anemic woman is more likely to die with less blood loss from postpartum hemorrhage than a woman with normal hemoglobin level. Other definitions of hemorrhage exist for instances when it is not feasible to accurately identify the level of blood loss. These refer to the need for a specified amount of blood transfusion or to a defined level of drop in hemoglobin level. Similarly, for another serious pregnancy outcome, preeclampsia, the cutoff levels to define high blood pressure differ in different definitions. Finally, some conditions, such as urinary incontinence, are difficult to define, as a distinction between normal physiological symptoms due to pregnancy and its pathology may not be clear-cut.

It is, however, essential to measure maternal morbidity as well as the deaths. Monitoring maternal morbidity has some major advantages over monitoring maternal deaths. Maternal morbidity occurs much more frequently than maternal deaths; hence information on maternal care can be more rapidly gathered and analyzed, allowing for more rapid feedback and intervention. The survival of the woman means that the woman can be interviewed to identify whether the health system failed or not. This is of particular value in women who have been referred from one institution to another, and especially for assessing care at the primary health-care level. This information on care provided at the primary level is often not available in the investigation of maternal deaths.

In countries with low numbers of maternal deaths, the causes of the deaths are often peculiar to the particular case. For example, congenital heart disease is an important contributor to maternal death in the United Kingdom, but congenital heart disease is a rare condition. Information gained from analyzing deaths due to congenital heart disease, although useful, is limited to those very few people with the condition. Hence, lessons learned cannot be generalized to the whole population.

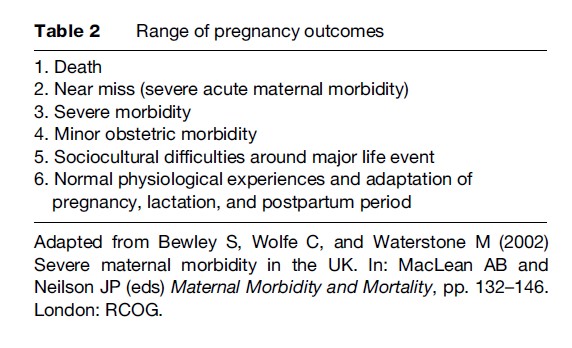

Several useful approaches to conceptualize maternal morbidity and to categorize the wide range of pregnancy outcomes exist. One approach classifies maternal morbidity based on the hierarchy of the severity of pregnancy outcomes. In this concept, the spectrum of the pregnancy outcomes ranges from death to normal physiological experiences, as shown in Table 2. The conditions that fall into categories 2–4 fit into the definition of maternal morbidity.

Maternal Death

Measurement

Although widely accepted standardized definitions of maternal mortality exist, as described above, it is difficult to accurately measure the level of maternal mortality in a population for several reasons. First, it is difficult to identify maternal deaths precisely. Particularly in settings where deaths are not reported comprehensively through routine registration systems, the death of a woman of reproductive age may not be recorded. Second, even if it is recorded, her pregnancy status may not be known and, third, even if the pregnancy status is known, where a medical certification of cause of death does not exist, correct attribution of death as a maternal death cannot be done. This means that even in settings where routine registration of deaths is in place, without special attention to enquiring about the causes of deaths, maternal deaths can go underreported. Chang and colleagues (2003) in their report of routine surveillance of maternal deaths in the United States during 1991–99, estimated that the true number of deaths related to pregnancy might increase 30–150% with active surveillance.

Where routine registration with correct cause– attribution of deaths does not exist, determination of the levels of maternal mortality relies on ad hoc population surveys. These surveys require very large sample sizes because, despite being unfairly high in some parts of the world, maternal deaths are relatively rare events in epidemiological terms. Even very large sample sizes produce estimates of maternal mortality levels with wide confidence intervals. Alternative methods to reduce the requirement for large sample sizes have been developed, but the problem of the large uncertainty margins remains.

Public health officials use statistical measures of maternal deaths primarily so that comparisons can be made over time or between areas. However, another aspect related to maternal death analysis is to detect where health systems fail. For this, only a large representative sample is needed. This is particularly useful in developing countries where inadequacies in data collection mean rates are not possible to calculate. Confidential enquiries into maternal deaths (CEMD) are a good example of this approach and are defined by WHO (2004) as:

A systematic multidisciplinary anonymous investigation of all or a representative sample of maternal deaths occurring at an area, region (state) or national level, which identifies the numbers, causes and avoidable or remediable factors associated with them. Through the lessons learnt from each woman’s death, and through aggregating the data, confidential enquiries provide evidence of where the main problems in overcoming maternal mortality lie and an analysis of what can be done in practical terms, and highlight the key areas requiring recommendations for health sector and community action as well as guidelines for improving clinical outcomes.

Measures Of Maternal Mortality

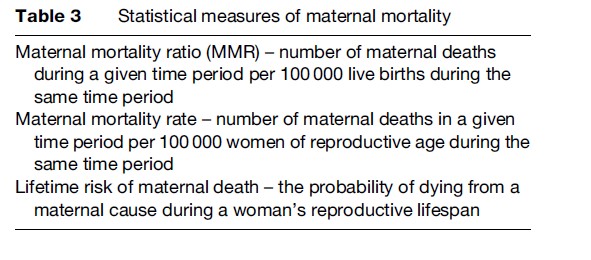

The maternal mortality ratio (MMR) is the most frequently used statistical measure to evaluate maternal mortality. This measure refers to the number of maternal deaths during a given time period per 100 000 live births during the same time period. It is a measure of the risk of death once a woman has become pregnant. Other less commonly used measures include maternal mortality rate and lifetime risk of maternal death, as shown in Table 3.

Data Sources And Collection Methods

Ideally, data for both the numerator (number of maternal deaths) and the denominator (number of live births) should be obtained by direct counting through routine registration systems with correct attribution of the causes of deaths as determined by medical certification. For reasons mentioned earlier, this does not exist in many countries. Even if such systems exist, underreporting is usually a problem and identification of the true numbers of maternal deaths requires additional specific investigations into the causes of deaths, even in developed countries. A specific example for such investigation is the CEMD for the United Kingdom, which was initiated in 1928.

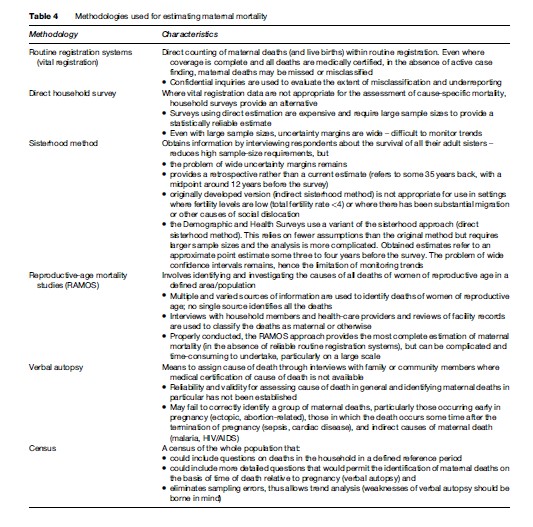

Alternatively, data are collected on an ad hoc basis using a variety of methods including direct household surveys, surveys using sisterhood methodology, reproductive-age mortality studies (RAMOS), and censuses. Derived estimates are based on respondents’ accounts of maternal deaths in the household or among their sisters (sisterhood methodology) or studies of deaths among women of reproductive age (RAMOS methodology). Questions investigate deaths of women during pregnancy, childbirth, or the defined postpartum period, thus pregnancy-related deaths. Main methodologies used for estimating maternal mortality levels are shown in Table 4.

Global Levels And Determinants

The difficulties in measuring the true extent of maternal mortality, particularly in less-developed countries, are well-established. Making international comparisons is also difficult due to the variety of methodologies used to determine maternal mortality in different settings and the different definitions used by different methodologies.

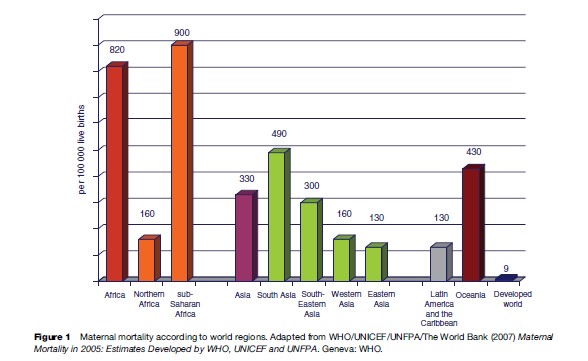

It is, however, clear that a vast difference between more developed and developing countries exists in levels of maternal mortality. WHO, together with the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and the World Bank, uses a methodology to calculate global estimates of maternal mortality in which countries are classified according to the availability of data from different sources and a modeling technique for those with no available reliable data is used. The most recent WHO publication of maternal mortality estimates (2007) refers to levels of maternal mortality in 2000 and shows an MMR of 450 in developing country settings and 9 in more developed regions. As shown in Figure 1 the highest maternal mortality levels were in Africa (820 maternal deaths per 100 000 live births) and the lowest in Latin America (130 maternal deaths per 100 000 live births) among the developing regions of the world.

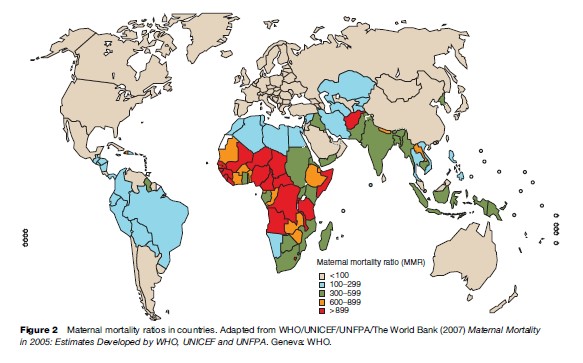

Countries in sub-Saharan Africa had very high levels of maternal mortality. For example, MMR was estimated as 2100, 1800, and 1500 in Sierra Leone, Niger, and Chad, respectively. In Afghanistan, 1800 women were estimated to have died from pregnancy-related causes per 100 000 live births. In contrast, maternal mortality ratios hardly exceed 9 per 100 000 live births in developed countries (Figure 2).

In addition to wide between-country differences, maternal mortality levels vary between subpopulations within countries, both more developed and developing. Ethnic group differences in the United States are among the most-cited examples of differentials of maternal mortality in developed settings. Anachebe and Sutton (2003) reported a fourfold disparity in the risk for maternal death among black women as compared to white women for 1987–96 in this country. In Germany, Razum and colleagues (1999) found that immigrant women were reported to be more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes as compared to their native counterparts. Women living in the most deprived areas of England had a 45% higher death rate as compared with women in the most affluent areas according to the CEMD 2004 in the United Kingdom for the years 2000–2002 (Lewis, 2004). Similar trends exist in developing countries. An analysis of nationally representative survey data from 10 developing countries (Graham et al., 2004) showed the consistent increase in probability of dying from maternal causes with increased poverty.

Between-country differences in maternal mortality levels reflect the differences in socioeconomic development of countries as well as the capacity and functioning of health systems to deliver effective interventions as needed. Within-country differences show that certain subpopulations are disadvantaged through a variety of characteristics. These characteristics make them vulnerable to maternal complications (e.g., poor living conditions and nutrition) as well as less able to seek and obtain appropriate health care (e.g., education, health-care access, quality of care) for the prevention or management of these complications.

Causes Of Maternal Deaths

As mentioned in the previous sections, maternal deaths are caused either by conditions specific to pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period and/or their management (direct causes) or by preexisting medical conditions (indirect causes). Direct causes include hemorrhage, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (preeclampsia, eclampsia), sepsis, obstructed labor, uterine rupture, obstetric embolism, ectopic pregnancy, complications of abortion, cesarean section, or anesthesia, and other less frequent conditions.

Indirect maternal deaths may occur due to chronic conditions such as cardiac or renal disease, or suicide due to pregnancy-related depression and psychosis. Nonpregnancy-related infections, including malaria and tuberculosis, are usually also regarded as indirect causes of maternal deaths. Deaths due to acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) are also often included as indirect deaths in the non-pregnancy-related infections category. Women rarely die due to AIDS alone, but rather due to a concomitant disease such as tuberculosis, Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, cryptococcal meningitis, and other common diseases, such as malaria and community-acquired pneumonia, that are made more severe by the underlying condition of AIDS. In areas with high HIV prevalence, it is more appropriate to classify all women with respect to their HIV status and their stage of disease rather than have AIDS as a specific primary obstetric cause of maternal death. Analysis of women with or without HIV infection and those with or without AIDS can then be performed and the full impact of the disease assessed. When AIDS is classified within the indirect causes, this may conceal the actual cause of death, for example, a septic abortion. (When a woman with AIDS dies, there is a tendency to report only AIDS and not other conditions directly responsible for the death but imminently treatable such as a septic abortion.)

Although not regarded as maternal deaths within the classic definition, accidental causes including trauma and homicide are increasingly becoming important in cause distributions of maternal deaths in developed countries, where mortality due to other causes is reduced with provision of effective health care.

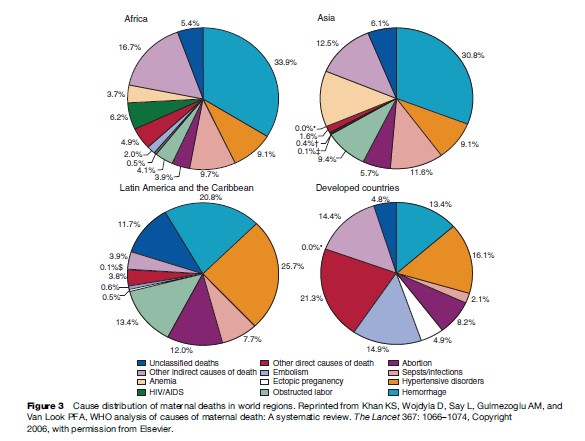

The patterns of the causes of maternal deaths vary according to the world regions due to the disease profiles in the regions as well as the extent of the development of health systems. An analysis of the causes of maternal deaths in the broad world regions (Khan et al., 2006) shows that hemorrhage is the leading direct cause of death in Africa (33.9%) and Asia (30.8%). In Latin America and the Caribbean, hypertensive disorders including preeclampsia and eclampsia are responsible for the largest number of deaths (25.7%). In more developed country settings, deaths due to a group of direct obstetric causes including complications of anesthesia are the biggest contributors to maternal deaths (21.3%) (Figure 3). Deaths related to infections, in particular HIV/AIDS, anemia, and abortion are the region-specific characteristics of distribution of maternal deaths in Africa, Asia, and Latin America and the Caribbean, respectively.

Another emerging pattern in the cause distribution of maternal deaths in developed countries with low maternal mortality ratios is the dominance of causes indirectly related to pregnancy, particularly worsening of preexisting medical conditions. The contribution of indirect conditions was 59% to all deaths in the United Kingdom CEMD for the years 2000–2002 (Lewis, 2004). In the United States, where MMR is slightly higher than in many European countries, one-third of maternal deaths during the 1990s were due to indirect morbidities including cardiomyopathy, complications of anesthesia, cerebrovascular accidents, and pulmonary or neurological problems, as reported by Chang and colleagues (2003). The shift from direct causes to indirect causes associated with chronic conditions is due to the relative decrease of deaths caused by direct morbidities as more developed health systems are able to prevent and treat these conditions.

Maternal (Obstetric) Morbidity

Severe Acute Maternal Morbidity (Near Miss)

The concept of severe acute maternal morbidity (SAMM) or ‘‘near miss’’ describes the severest type of maternal morbidity, defined by Mantel and colleagues (1998) as: ‘‘A very ill pregnant or recently delivered woman who would have died had it not been that luck and good care was on her side.’’

This concept is relatively new in maternal care, but is increasingly becoming an important indicator of pregnancy-related risks and the quality of maternal health care. Particularly where maternal deaths are becoming less frequent or the geographic area is small, investigation of the low numbers of maternal deaths gives information relevant only to the limited number of cases. Examination of the cases that almost died, however, provides richer information on the quality of the health care in relation to common major morbidities in a particular setting.

Maternal deaths in developed countries are now rare, and the factors that surround the death are often peculiar to the event and are not generalizable. This does not mean that pregnancy is a safe condition in developed countries. Waterstone and colleagues (2001) reported a severe obstetric morbidity rate of 12.0 per 1000 births, and a severe morbidity to mortality ratio of 118:1 in the South East Thames region in London. Contrary to what would be expected, the common causes of maternal mortality are not the same as the common causes of maternal morbidity in developed country settings. A review of only maternal deaths would neglect the important life-threatening other obstetric emergencies, which are common causes of morbidity in London, such as antepartum hemorrhage, postpartum hemorrhage, and preeclampsia. The most common cause of severe morbidity was severe hemorrhage at 6.7 per 1000 births in the London area. This is not unique to London, as the most common cause of near misses in Scotland (Brace et al., 2004) was also hemorrhage. In comparison, there were only seven deaths in over 2 million deliveries (3.3 deaths per million deliveries) due to hemorrhage in the United Kingdom CEMD for the years 1997–99 (Lewis, 2001).

By looking at maternal deaths only, developed countries might be in danger of overlooking other major causes of morbidity in obstetric care. This might have already happened in the United Kingdom, as in the next triennium (2000–2002), according to the CEMD, there were 17 deaths (8.5 deaths per million deliveries) due to hemorrhage, a 140% increase (Lewis, 2004). A systematic analysis of severe morbidity would have kept hemorrhage as a priority condition, and the increase in deaths due to hemorrhage may potentially have been prevented. The new challenge in developed countries is to ensure that the gains made are sustained. Morbidity analysis will help in ensuring this, as resources will not be diverted away and health workers’ training will not neglect conditions such as hemorrhage.

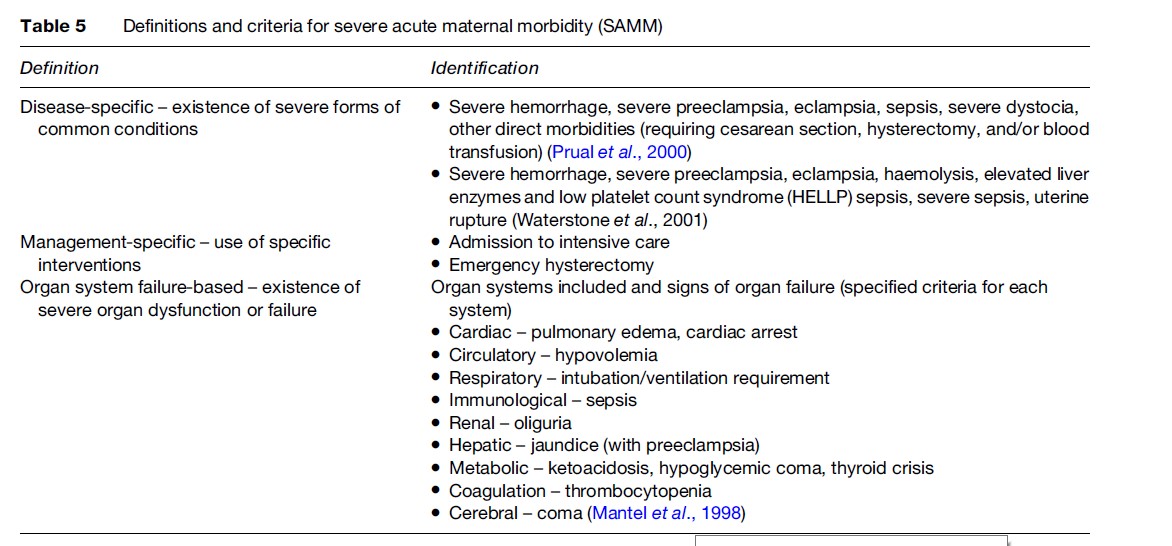

Operational definitions to identify SAMM cases include those according to existence of specified conditions (disease-specific); use of specific interventions or management techniques (management-based); and existence of organ failure (organ system-based) (Table 5).

Prevalence of SAMM varies according to which definition is used. Rates vary between 0.80–8.23% with disease-specific and between 0.38–1.09% with organ system-based definitions (Say et al., 2004). Rates are lower (0.01–2.99%) with management-based definitions. As expected and similar to MMR, prevalence of SAMM varies between less developed and more developed countries. In less developed countries, 4–8% of pregnant women who deliver in hospitals experience SAMM when diagnosis is made on the basis of specific diseases. This rate is around 1% when organ system failure is considered. In more developed country settings, the rates are around 1% with disease-specific and 0.4% with organ-system-based criteria, respectively.

In-depth reviews of SAMM cases in terms of the health care that the cases received give detailed information on how particular types of cases are managed and where the gaps and weaknesses are in the process of care. The use of a combined measure of mortality and morbidity also provides a crude indicator of the quality of care. One approach to construct such a measure is to divide the number of the cases identified as severe morbidity by those of deaths (morbidity-to-mortality ratio). The drawback of this approach is that although severe morbidity and mortality are expected to rise and fall equally (in the same setting), they may be independent. A second approach is to calculate the ratio of maternal deaths to the sum of maternal deaths and SAMM cases (mortality index, or MI). This measure gives the proportion of women with SAMM who die.

Morbidity-to-mortality ratio is typically 10-fold higher in studies undertaken in developed countries as compared to those in developing countries. For example, MI was calculated as 5–8 and 49 in South African and Scottish studies, respectively, that used the same case identification criteria (Say et al., 2004).

Major Morbidities

Major conditions that lead to SAMM and/or maternal death are classified under this category and include obstetric hemorrhage (antepartum, postpartum), preeclampsia/ eclampsia, pregnancy-related infections (mainly postpartum sepsis), thromboembolism, and obstructed labor (by leading to postpartum hemorrhage, sepsis, and uterine rupture) as direct maternal morbidities. Complications of abortion, when performed under unsafe conditions, constitute a major cause of maternal death through hemorrhage, infection, or uterine rupture. Other direct major morbidities are complications of ectopic pregnancy, anesthesia, or cesarean section.

Major morbidities include indirect causes of maternal deaths such as those that are based on preexisting medical conditions (e.g., chronic hypertension, cardiac or renal disease, diabetes, asthma, anemia) or suicide due to pregnancy-related depression, as well as non-pregnancy-related infections during pregnancy such as AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis.

Obstetric Hemorrhage

Hemorrhage is the major cause of maternal deaths in many settings. It can cause up to one-third of maternal deaths in settings with less-developed health systems. Because of the variety of definitions and difficulties in assessing the blood loss involved, the incidence of hemorrhage cannot be determined precisely. Severe hemorrhage was reported in 3.05% of women delivering live babies in six African countries and 0.67% of deliveries in the United Kingdom. Approximately 3% and 0.3% of these cases died in the African countries and the United Kingdom, respectively (Prual et al., 2000; Waterstone et al., 2001).

Hemorrhage may occur during pregnancy, either antepartum (due to placenta previa or placental abruption) or, most commonly, postpartum (due to uterine atony, retained placenta, inverted or ruptured uterus, or cervical, vaginal, or perineal laceration). The majority of cases occur immediately after delivery (immediate postpartum hemorrhage) and the most common cause is uterine atony, that is, the failure of the uterus to contract after delivery. Risk factors for uterine atony include preeclampsia, prolonged labor, high parity, induction of labor, high doses of halogenated anesthetics, prior postpartum hemorrhage, and large or multiple fetuses. However, as many as two-thirds of women who have postpartum hemorrhage do not have any of these risk factors. Late (or secondary) postpartum hemorrhage occurs after the first 24 h of delivery and can be due to retained placenta, infection, or trophoblastic tumors.

Postpartum hemorrhage is traditionally defined as the loss of more than 500 ml of blood after completion of the delivery, although the accurate measurement of the amount of the blood loss has been problematic. When measured objectively, 500 ml of blood loss is observed in approximately half of normal vaginal deliveries. Clinically estimated loss of 500 ml or more, however, is considered as significant since clinical estimates of blood loss are found to be about half of the actual loss (objectively measured) (Pritchard et al., 1962). This definition is particularly relevant to developing country settings, where women are more vulnerable to negative consequences of blood loss due to limitations of the delivery care they usually receive or to preexisting severe anemia. In developed country settings, blood loss of 1500 ml or more is usually defined as severe hemorrhage.

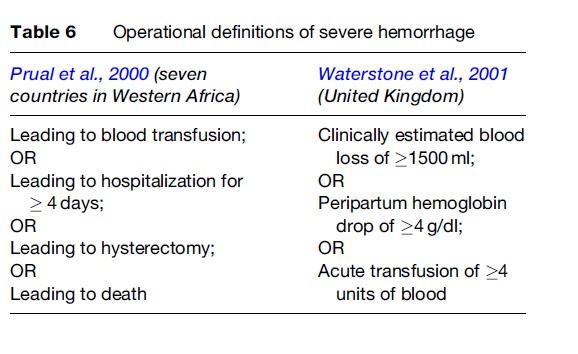

Other practical definitions of severe hemorrhage also exist since accurate measurement is not always feasible and clinical estimations are not reliable. Drop of a specified quantity in hemoglobin or hematocrit levels or the amount of blood transfused are alternative practical definitions of severe hemorrhage. Operational definitions used in two classic studies of severe morbidity in developing and developed country settings are shown in Table 6.

Severe hemorrhage can lead to SAMM or death in a very short period if not managed properly. Management depends on the cause and the severity of the bleeding. For example, hemorrhage due to uterine atony is managed by stopping the bleeding using uterotonics, physical compression techniques, uterine artery ligation, or hysterectomy, as well as replacement of fluid, clotting factors, and blood that have been lost due to the bleeding. Additional treatment will involve removal of retained fragments in the case of retained placenta, suturing in case of lacerations, and hysterectomy or repair in case of uterine rupture.

Postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine atony can be prevented in most instances. An intervention package involving administration of uterotonic agents, controlled cord traction, and uterine massage, referred to as active management of the third stage of labor, was shown to be effective in reducing the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage. Active management is therefore preferred over expectant management, which involves waiting for signs of placental separation and allowing for spontaneous delivery of the placenta.

Other measures to prevent hemorrhage include administering a uterotonic agent alone, reducing the incidence of obstructed labor by timely intervention as needed, minimizing the trauma due to instrumental delivery, and detection and treatment of anemia during pregnancy.

Hypertensive Disorders Of Pregnancy (Preeclampsia/Eclampsia)

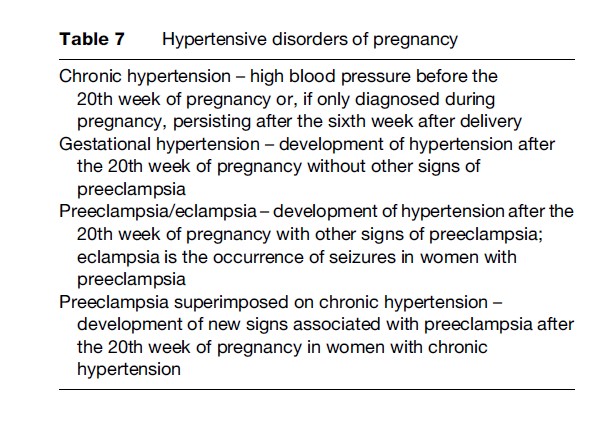

Pregnancy-specific hypertensive conditions, in particular preeclampsia/eclampsia, are among the leading causes of SAMM and maternal deaths. Four types of such conditions complicate pregnancy (Table 7).

As seen in Figure 3, 9–29% of maternal deaths are caused by hypertensive disorders in world regions. Hypertension complicates approximately 5% of all and 11% of first pregnancies, respectively. Preeclampsia constitutes half of these cases (2–3% of all pregnancies and 5–7% of first pregnancies). Between 0.8–2.3% of women with preeclampsia develop eclampsia (Magpie Trial Collaborative Group, 2002). Similar to hemorrhage, the likelihood of dying from preeclampsia or eclampsia is much higher in developing country settings than in more developed ones. Around 5% of women with eclampsia and 0.4% with preeclampsia die in developing country settings. These figures are as low as 0.7% and 0.03%, respectively, in more developed countries.

Preeclampsia is a multisystem disorder usually characterized by sudden onset of hypertension and proteinuria during the second half of pregnancy. The basic causes are changes in the endothelium, which is an intrinsic part of all blood vessels. Preeclampsia, therefore, has the potential of affecting any organ system. The nature of the signs and symptoms varies according to which organs are affected. In addition to hypertension, proteinuria, oliguria, cerebral or visual disturbance, pulmonary edema, cyanosis, thrombocytopenia, or signs of impaired liver function can be detected in a preeclamptic woman. It is, however, proteinuria and hypertension that are the defining features of preeclampsia.

A variety of definitions of preeclampsia with different specifications for both features is used, particularly for research purposes. Clinically:

- hypertension is defined as blood pressure of equal to or greater than 140 mmHg systolic or 90 mmHg diastolic in two consecutive measurements and occurring after the 20th week of pregnancy

- proteinuria is defined as a protein concentration of more than 500 mg/l in a random specimen of urine or a protein excretion of more than 300 mg per 24 h

- eclampsia is the occurrence of seizures in a woman with preeclampsia.

Women with first pregnancy, extremes of age, obesity, multiple pregnancy, preexisting hypertension or renal disease, who have had preeclampsia or eclampsia in a previous pregnancy, and with a family history of pregnancy are more at risk of developing preeclampsia.

Identification of reduced placental perfusion or vascular resistance dysfunction by Doppler ultrasonography or high levels of urinary kallikrein may be useful in diagnosing preeclampsia during early pregnancy, but widespread use of these techniques, particularly in resource-poor settings, is limited due to technological requirements. Regular screening of blood pressure, urinary protein, and fetal size during antenatal care visits is currently the only strategy for early diagnosis of preeclampsia. High-risk women should be screened more frequently between 24 and 30 weeks of pregnancy, when the onset of the disease is most common.

If the hypertension is severe (blood pressure≥ 170 mmHg systolic or ≥110 mmHg diastolic), treatment should include antihypertensive drugs. The effectiveness of antihypertensive treatment in mild to moderate hypertension has not been established. Magnesium sulfate is the drug of choice for preeclampsia to prevent eclampsia, as well as for eclampsia to reduce recurrence of convulsions and maternal death.

Studies on the effectiveness of a range of nutritional (vitamins, antioxidants) or non-nutritional (antiplatelet agents, calcium) strategies to prevent preeclampsia have provided no conclusive evidence. The only recommended strategy is the use of low-dose aspirin in high-risk nulliparous women and women with poor obstetric history.

Sepsis

Sepsis, in particular, postpartum sepsis, is an important cause of maternal death in developing countries, but is very rare in more developed countries where historically most of the deaths were due to sepsis. The invention and widespread use of antibiotics and recognition of the importance of clean delivery practices with skilled delivery attendants brought a sharp decline in the number of maternal deaths, in particular those caused by postpartum sepsis, during the first half of the 20th century. Currently, less than 1% of deliveries in developed country settings are complicated with sepsis, which usually results from rare hospital infections.

Sepsis is a systematic response to infectious agents or their byproducts. It develops most frequently from urinary tract infections, chorioamnionitis, postpartum fever (due to pelvic infection, surgical procedures, endometritis), or septic abortion. The infectious agents are either endogenous (i.e., they already exist as part of the normal flora of the woman’s genital tract or as an existing infectious agent) or exogenous (i.e., acquired from outside sources such as deliveries or abortions taking place under unhygienic conditions) and most frequently include Streptococcus, Gramnegative bacteria, gonococcus, chlamydia, herpes simplex, and the organisms causing bacterial vaginosis. The effects of malaria and HIV/AIDS in areas where these infections are frequent are also increasingly recognized, although the mechanisms by which these infections cause sepsis are not clearly identified.

The usual signs of infection, such as fever, tachycardia, and leukocytosis at the early stages, if not treated appropriately, convert to severe sepsis with signs of multiple organ effects, such as hypothermia, hypotension, encephalopathy, oliguria, and thrombocytopenia. This can further lead to septic shock, which is a highly lethal syndrome in both developing and developed countries.

Management of sepsis involves treatment of the causative agent with appropriate antibiotics and interventions targeted to deal with presenting signs, such as hypovolemia, encephalopathy, or clotting problems.

Sepsis is preventable by:

- treatment of existing infection with appropriate antibiotics;

- prophylactic use of antibiotics for cesarean section, for women with preterm pre-labor rupture of membranes, and for high-risk women (women with previous spontaneous preterm delivery, history of low birthweight, prepregnancy weight less than 50 kg, or bacterial vaginosis in the current pregnancy); and

- clean delivery/pregnancy termination practices (infection control), including hand hygiene of providers and use of sterile, preferably disposable, supplies and equipment.

Obstructed Labor

Obstructed labor is the failure of labor to progress due to mechanical obstruction. The source of the problem may be the mother (such as a contracted pelvis or tumor causing obstruction), the baby (such as a large or abnormal baby or abnormal position, presentation, or lie), or both. Most frequently, the problem is related to a relative size discrepancy between a normal baby and the pelvis of a healthy mother. In women experiencing their first pregnancy, obstructed labor usually leads to decreasing uterine activity and prolonged labor with the possibility of infection, postpartum hemorrhage, and vesicovaginal fistula formation, whereas in multiparous women uterine activity may continue to the point of uterine rupture.

Poor progress of labor may be due to obstruction, cervical dystocia, inefficient uterine activity, or a combination of these. The clinical diagnosis is usually based on poor progress of labor despite adequate uterine activity, together with visible signs of obstruction such as molding of the fetal skull. The definition of obstructed labor generally involves the length of labor (such as >12 or >18 h, or second stage >2 h), although other definitions involving clinical signs (such as uterine ring, pre-rupture, second stage transverse lie) are also used. According to the unpublished data from the WHO database of maternal mortality and morbidity, prevalence (with the definition of labor lasting >18 h) is in general less than 1% in developed country settings and may be up to 5% in less developed countries.

Black race, short maternal height, and maternal obesity were suggested as potential risk factors, although there are no agreed criteria for their use to predict obstructed labor. In settings where common, scarring due to female genital mutilation may cause obstructed labor. Women with previous obstructed labor are at risk of experiencing future obstruction.

In settings with ready access to safe cesarean section, the management of obstructed labor is straightforward and related maternal mortality is extremely rare, although perinatal and maternal morbidity may occur. However, when cesarean section is not readily accessible, obstructed labor is a major cause of maternal mortality and severe morbidity by leading to uterine rupture, postpartum hemorrhage, sepsis, and obstetric fistula. Uterine rupture is a serious complication of obstructed labor, particularly in less developed settings. In developed countries, uterine rupture is typically seen in women with scarred uterus due to previous cesarean section.

The widely accepted interventions for preventing obstructed labor are the correction of breech presentation by external cephalic version at term and cesarean section. When cesarean section is not available or unsafe, symphysiotomy is a life-saving intervention for both the mother and the baby, although it has long been regarded as an unacceptable operation due to the perceptions of complications.

Venous Thromboembolism

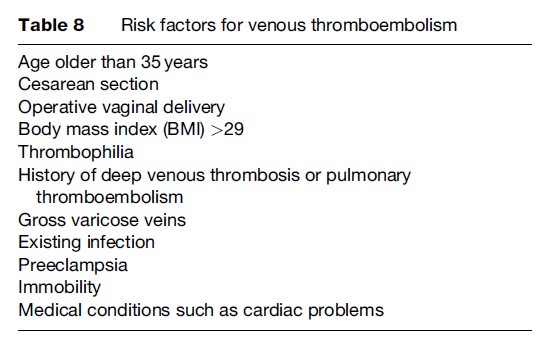

Venous thromboembolism refers to two related conditions – venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism – that affect pregnant women. Pulmonary embolism arises from venous thrombosis, which is the process of clotting within the veins. It represents the leading cause of maternal deaths in developed country settings, despite being a rare event with a prevalence of less than 1%. Major risk factors for venous thromboembolism in pregnant women are shown in Table 8.

Venous thrombosis predominantly occurs in the legs and presents with clinical signs of pain, discomfort, swelling, and tenderness in the affected leg. Because problems such as swelling of the legs and discomfort are common in normal pregnancies, the clinical diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis is difficult. Only 10% of pregnant women who have such symptoms are diagnosed with deep venous thrombosis. It is, however, important to objectively diagnose the condition, because approximately one-fourth of women with untreated deep venous thrombosis develop pulmonary embolism.

In the majority of the cases where the thrombus is in the legs, the abovementioned clinical signs precede pulmonary embolism, but in others, where the thrombus is in the pelvic veins, the woman is usually asymptomatic until pulmonary embolus occurs. The most common clinical signs of pulmonary embolism are breathlessness, chest pain, cough, collapse, and hemoptysis. Advanced techniques such as compression ultrasonography and sophisticated computerized tomography scanners are used to diagnose deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, respectively.

The exact strategy to manage venous thromboembolism during pregnancy is still debated, but treatment generally includes the use of appropriate anticoagulants, mostly heparin. In deep venous thrombosis, the use of anticoagulants decreases the risk of developing embolism to less than 5%. Limitation of activity and use of elastic stockings are the recommended supportive measures. Anticoagulant use should be continued following delivery, but the evidence on the optimum length of use is limited. Current practice is to continue for at least 6 weeks. Thromboembolism can recur; thus, pregnant women with a previous event should be given prophylactic anticoagulants.

Other Major Morbidities

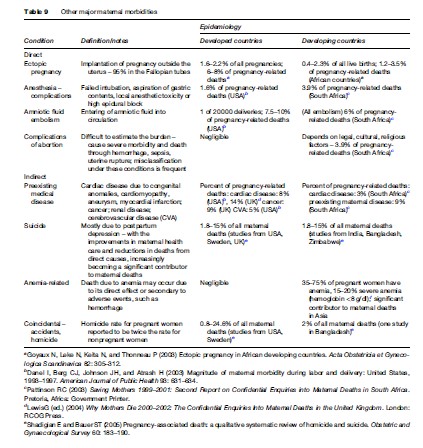

A summary of other contributors of severe maternal morbidity and mortality not examined above is shown in Table 9. A final category that requires special attention is the effect of non-pregnancy-related infections – namely those of AIDS and malaria. These are classified among the indirect causes of maternal deaths as a subcategory of non-pregnancy-related infections.

The Effect Of AIDS

The most significant evidence on the contribution of AIDS to maternal deaths comes from the CEMD in South Africa (Pattinson, 2003, 2006). The inquiry attributed 17.0% and 20.1% of all maternal deaths to AIDS in 1999–2001 and 2002–2004, respectively. Moreover, the increase of deaths in hemorrhage, sepsis, and other nonpregnancy-related infections compared to the previous years was also suggested to be due to the effect of AIDS.

The mechanisms by which AIDS causes maternal deaths have not been clearly identified. There is some evidence from developing countries that pregnancy may be accelerating the disease, particularly in late stages. The presence of AIDS increases the severity of the complications of pregnancy and delivery, including ectopic pregnancy, spontaneous abortion, bacterial pneumonia, urinary tract infections, opportunistic infections (such as tuberculosis) and other infections, preterm delivery, hemorrhage, and sepsis that might eventually cause death. It appears that both the effects of infection and its complex interaction with related medical and social conditions that affect pregnancy are possible explanations of increased adverse pregnancy outcomes due to AIDS.

The Effect Of Malaria

The proportion of maternal deaths attributable to malaria ranges between 2.9–17.6% in community-based studies in Africa (Brabin and Verhoeff, 2002), although the causal pathways between the infection and death, as in HIV, have not been established. The contribution of malaria to maternal deaths might be through its association with preeclampsia, eclampsia, hemorrhage, sepsis, and anemia. It has also been suggested that comorbidity with HIV increases malaria-related maternal deaths. In addition, pregnant women are more susceptible to infection than nonpregnant women are, and preventive measures should be a part of antenatal care where malaria is endemic.

Minor Morbidities

Obstetric Trauma

Conditions that do not lead to serious maternal morbidity or death but cause long-term disability are included under this category. Sequelae of obstetric trauma, such as episiotomies or lacerations that are inappropriately managed and obstetric fistula, can cause lifelong suffering in varying degrees.

Lacerations involving the anal muscle and sphincter may cause rectal incontinence and uterine prolapse by weakening the support provided by the pelvic diaphragm. High parity, episiotomy, and cesarean section increase the risks of fecal or flatus incontinence. Urinary incontinence occurs with deep lacerations of the anterior vaginal compartment following spontaneous, forceps, or vacuum delivery.

Obstetric fistula (vesicovaginal or rectovaginal) occurs due to prolonged obstructed labor when the genital tract is compressed between the fetal head and the bony pelvis. Prolonged pressure may result in necrosis with subsequent vesicovaginal fistula formation, causing an uncontrollable pass of urine from the vagina. Rarely, vesicocervical fistula occurs when the anterior cervical lip is compressed against the symphysis pubis. Rectovaginal fistula occurs in a similar way to vesicovaginal fistula. In this case, holes form between the tissues of the vagina and rectum, leading to uncontrollable leakage of feces. Some of these fistulas may heal spontaneously but, more often, special repair is necessary. Despite appropriate repair, Murray and colleagues (2002) reported persistence of urinary incontinence in 55% of cases in Ethiopia.

Psychological/Psychiatric Problems

Pregnancy may be associated with a level of anxiety reflecting fears surrounding delivery and the health of the baby, which, in some women, can lead to clinically meaningful levels of anxiety and depression. Sustained, high levels of anxiety may cause preterm delivery, prolonged delivery, and higher levels of delivery complications. Such anxiety also increases the risk of developing postpartum depression, which is the commonest cause of suicide among postpartum women, followed by postpartum psychosis. Suicide in the postpartum period is among the leading causes of maternal death, particularly in developed countries (Table 9).

Conclusion

Pregnancy and childbirth may have negative outcomes ranging from minor conditions to more serious morbidities and even death. Among all maternal deaths, 99% occur in developing parts of the world, where maternal morbidities are also more prevalent. The classic major severe morbidities of pregnancy contribute to a smaller part of the relatively few maternal deaths in developed countries because these conditions are preventable and treatable. In these settings, rare conditions, such as obstetric embolism, worsening of preexisting medical conditions, and depression-associated suicide have become the largest contributors of maternal deaths. In developing countries, the major direct morbidities are still the main causes of maternal deaths, together with emerging infections such as AIDS and malaria or anemia. The patterns of maternal mortality and morbidity reflect the level of development of the health systems to be able to cope with severe consequences of major maternal morbidities. Public health challenges of maternal health remain to:

- accurately measure the extent of the mortality and morbidity and establish the patterns of both,

- address the weaknesses of health systems at both technical and functional levels, and

- ensure inclusion of populations that are most vulnerable in the delivery of services.

Bibliography:

- Anachebe NF and Sutton MY (2003) Racial disparities in reproductive health outcomes. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 188: S37–S42.

- Bewley S, Wolfe C, and Waterstone M (2002) Severe maternal morbidity in the UK. In: MacLean AB and Neilson JP (eds.) Maternal Morbidity and Mortality, pp. 132–146. London: Royal College of Gynaecology

- Brabin BJ and Verhoeff F (2002) The contribution of malaria. In: MacLean AB and Neilson JP (eds.) Maternal Morbidity and Mortality, pp. 64–78. London: Royal College of Gynaecology.

- Brace V, Penney G, and Hall M (2004) Quantifying severe maternal morbidity: A Scottish population study. British Journal of Gynaecology: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 111: 481–484.

- Chang J, Elam-Evans LD, Berg CJ, et al. (2003) Pregnancy-related mortality surveillance: United States, 1991–1999. Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report 52: 1–8.

- Danel I, Berg CJ, Johnson JH, and Atrash H (2003) Magnitude of maternal morbidity during labor and delivery: United States, 1993–1997. American Journal of Public Health 93: 631–634.

- Goyaux N, Leke N, Keita N, and Thonneau P (2003) Ectopic pregnancy in African developing countries. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 82: 305–312.

- Graham W, Fitzmaurice AE, Bell JS, and Cairns JA (2004) The familial technique for linking maternal death with poverty. Lancet 363(9402): 23–27.

- Khan KS, Wojdyla D, Say L, Gulmezoglu AM, and Van Look PFA (2006) WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: A systematic review. Lancet 367(9516): 1066–1074.

- Lewis G (ed.) (2001) Why Mothers Die 1997–1999: The Confidential Enquiries Into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. London: RCOG Press.

- Lewis G (ed.) (2004) Why Mothers Die 2000–2002: The Confidential Enquiries Into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. London: RCOG Press.

- Magpie Trial Collaborative Group (2002) Do women with preeclampsia, and their babies, benefit from magnesium sulphate? The Magpie Trial: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 359: 1877–1890.

- Mantel GD, Buchmann E, Rees H, and Pattinson RC (1998) Severe acute maternal morbidity: a pilot study of a definition for a near-miss. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 105: 985–990.

- Murray C, Goh JT, Fynes M, and Carey MP (2002) Urinary and faecal incontinence following delayed primary repair of obstetric genital fistula. British Journal of Gynaecology: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 109: 828–832.

- Pattinson RC (ed.) (2003) Saving Mothers 1999–2001: Second Report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in South Africa. Pretoria, Africa: Government Printer.

- Pattinson RC (ed.) (2006) Saving Mothers 2002–2004: Third Report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in South Africa. Pretoria, Africa: Government Printer.

- Pritchard JA, Baldwin RM, and Dickey JC (1962) Blood volume changes in pregnancy and the puerperium, 2. Red blood cell loss and changes in apparent blood volume during and following vaginal delivery, cesarean section and cesarean section plus total hysterectomy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 84: 1271–1282.

- Prual A, Bouvier-Colle MH, De Bernis L, and Breart G (2000) Severe maternal morbidity from direct obstetric causes in West Africa: incidence and case fatality rates. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 78: 593–602.

- Razum O, Jahn A, Blettner M, and Reitmaier P (1999) Trends in maternal mortality ratio among women of German and non-German nationality in West Germany 1980–1996. International Journal of Epidemiology 28: 919–924.

- Say L, Pattinson RC, and Gulmezoglu AM (2004) WHO systematic review of maternal morbidity and mortality: the prevalence of severe acute maternal morbidity (near miss). Reproductive Health 1(1): 3.

- Shadigian E and Bauer ST (2005) Pregnancy-associated death: a qualitative systematic review of homicide and suicide. Obstetric and Gynaecological Survey 60: 183–190.

- Van der Broek N (2002) The contribution of anaemia. In: MacLean AB and Nelson JP (eds.) Maternal Morbidity and Mortality, pp. 79–88. London: Royal College of Gynaecology.

- Waterstone M, Bewley S, and Wolfe C (2001) Incidence and predictors of severe obstetric morbidity: case-control study. British Medical Journal 322: 1089–1094.

- WHO/UNICEF/UNFPA/The World Bank (2007) Maternal Mortality in 2005: Estimates Developed by WHO, UNICEF and UNFPA. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

- World Health Organization (1992) International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10). Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

- World Health Organization (2004) Beyond the Numbers: Reviewing Maternal Deaths and Complications to Make Pregnancy Safer. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

- Critchley H, MacLean A, Allan PL, and Walker J (eds.) (2003) Preeclampsia. London: Royal College of Gynaecology Press.

- Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, et al. (eds.) (2005) Williams Obstetrics, 22nd edn. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- MacLean AB and Neilson JP (eds.) (2002) Maternal Morbidity and Mortality. London: Royal College of Gynaecology Press.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.