This sample Measurement of Psychiatric and Psychological Disorders Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

The measurement of mental and behavioral disorders poses three particular challenges. First, there are no laboratory or similar independent confirmatory diagnostic technologies; instead, the nature of these disorders requires the collection of subjective psychological information on inner states of feeling, thinking, and perceiving, together with, sometimes, reliable information on behavior over time. Second, nearly all measures involve a retrospective element that relies on recall, whereas ideally information should be collected prospectively, requiring a more costly longitudinal element. Third, there is the challenge of achieving external or criterion validity.

This research paper covers the principles of measurement in psychiatric epidemiology, including discussions around international aspects (e.g., cross-population issues, including excluded groups, and issues of culture), measurement of specific disorders, and application of measurement methods in public health contexts (e.g., surveillance and screening in health settings). Enormous progress has been made in developing and applying such methods, including their use in very large-scale international surveys in recent years. Policy and decision makers can now readily access the information they need but must first understand the potential and limitations of current measurement methods.

It is assumed that the reader of this research paper is already familiar with basic clinical measurement, epidemiological, and public health concepts. This research paper points selectively to the ways in which such concepts have been developed in relation to measurement and public mental health. In order to illustrate this with the most up-to-date examples, we refer to survey methods used in Great Britain to collect information for policy on children (Green et al., 2005), adults, and older people (Singleton et al., 2001), but we also refer to more widely known, similar methods used elsewhere in relation to studies of the adult population, including high-quality national surveys in low-income countries. Such surveys have generated not only official government and policy reports but also numerous articles in academic journals. This research paper begins with a discussion of the nature of mental disorder, study design and measurement issues, procedures and techniques, and the interpretation of findings.

Nature Of Mental Disorder

For further reading please see Farmer et al. (2002).

Psychopathology

Concepts of psychopathology were first described in the clinical literature on severe mental disorders such as psychosis in the nineteenth century (Farmer et al., 2002). Attempts to define these with a view to their reliable measurement developed in the following century (Wing et al., 1974). Soon after this, work was extended to a wide range of mental and behavioral disorders to support the emergence of detailed mental disorder classification systems (World Health Organization Division of Mental Health, 1992; World Health Organization, 1992, 1993; American Psychiatric Association, 1994).

The psychopathology of mental disorders can be considered in terms of specific mental functions. Emotion in the form of mood and anxiety is given prominence in such systems with relatively little attention given to other emotions such as anger or happiness (except in the form of inappropriate elation in mania or bipolar disorder). Abnormalities of the experience and perception of reality in the form of psychotic hallucinations is given prominence, together with beliefs that are clearly false and not shared with another person (in contrast to subculturally approved beliefs). Cognitive impairment as seen in mental retardation (also known as learning disability or as intellectual disability) and dementia also receive prominence. Problems due to misuse of psychoactive drugs and their effects on mental functioning have taken greater prominence in recent years. New areas hardly touched on in surveys include developmental, behavioral, and personality abnormalities.

Definition And Classification Of Disorders

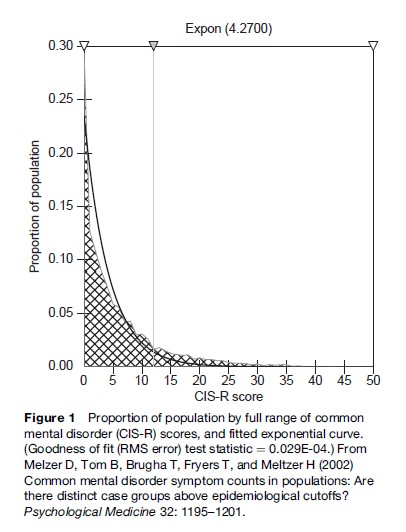

Until now the official classification systems (American Psychiatric Association, 1994; World Health Organization Division of Mental Health, 1990) have relied exclusively on binary definitions of disorders (Brugha, 2002): either the person has or does not have the disorder. This has been an enormously important and successful development in helping mental disorders to be considered and included in general health policy debates. However, critics have questioned the large number of categories of mental disorder, most of which would not register in surveys of public mental health in the general population anyway. Furthermore, the underlying nature of common mental disorder is likely to be dimensional without obvious cut points representing a diagnostic threshold (Figure 1). Dimensional approaches are, however, promised in future revisions of the classification system. Even within the ICD-10 system, depression is described in terms of levels of severity. Subthreshold levels are likely to be given greater prominence in the future in much the same way that clinical medicine increasingly recognizes the significance of lower levels of blood pressure or of serum lipids in terms of prediction of future morbidity. A stepped-care approach to the management of depression that uses these different levels of severity is already officially recommended in Great Britain by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. This is important for policymakers to consider because it implies that most (but not all) published prevalence tables for depressive disorder do not take into account such clinically significant distinctions.

Purposes Of Epidemiological Methods (Epidemiological Estimates, Modeling Determinants, Treatment Planning, And Needs Assessment)

It makes sense that any data collection using epidemiological methods should be preceded by a careful consideration of the purposes for which they will be used. Yet convention often seems to overtake such considerations.

A key question should be whether the purpose is research, audit, or surveillance. Research should aim to answer a key question and related subsidiary questions and should be designed and planned as such. The purpose of audit is to improve a process or service by examining its functioning against defined objectives and standards; audit should not be carried out without inclusion of a process for correcting flaws in the process or service being audited. Surveillance is similar to audit but is designed to monitor trends in populations over time and to alert decision makers to any changes that require early or urgent action.

A further difficulty may lie in a misunderstanding of the differences between clinical and epidemiological assessment. The measurement of psychiatric disorders in national surveys, which aim to provide population estimates, differs substantially from methods used in judicial and clinical decisions, for example, for benefits, compensation, and need for services. Methods used for assessing individuals, say, for a treatment program, are rarely the same as those required in epidemiology for classifying populations. In the case of the former, detailed and time-consuming assessments by a range of professionals of contexts such as family situations are justified because such methods are sensitive to individual circumstances and produce results that are equitable between individuals. In surveys, provided that the methods used deal adequately with the majority of people and can be done within a relatively short time, it matters little if a small minority have been classified differently than they would had more detailed procedures been used.

Quality Of Data

Conclusions regarding epidemiological estimates, the modeling of possible determinants, service planning, and needs assessment all require the use of comparisons. Comparisons have little value or legitimacy if the data employed are not collected reliably. The types of measures available are discussed later in this research paper. Because it is essential that epidemiological methods are reproducible (reliable), comparison may be either too costly or impractical when purely clinical measures are used. However, it is also important in developing either a new measure or in using an existing measure in a population with different language or culture, that it is generally accepted as representing descriptions used in clinical settings. Small-scale comparisons of epidemiological questionnaires and systematic clinical evaluations have been carried out occasionally in general population samples. At first sight the level of agreement between these appears to be poor and likely to be limited by the uncertain consistency with which clinical assessments can be used outside in the general population where most conditions are less severe and more fluctuant over time. It is reassuring therefore that clinical and epidemiological measures, when compared in clinical settings, can show high levels of agreement.

Design Issues

Study designs can be divided into the experimental and nonexperimental; the former are infrequently used in the collection of information on psychiatric and psychological disorders in the general population. New mental health policies are seldom subjected to the rigors of experimental evaluation in the general population, although where feasible this can be particularly informative. One experimental design variant that may be particularly feasible in practice is the cluster randomized evaluation. Examples are beginning to appear in the mental health field in which the cluster is an organizational unit, for example, a primary care practice, a specialist team: existing and new policies can be compared between randomly allocated cluster units (MacArthur et al., 2002). Another example makes use of the classroom or work team unit, which could be used in prevention policy trials. As in any experiment involving human subjects, ethical considerations arise: interventions can have wanted and unwanted effects, and those participating should be informed. Careful consideration should be given to anticipating possible harm and minimizing its likelihood; experiments are only justifiable when there is genuine uncertainty about the outcome.

A detailed discussion of the use of different designs in psychiatric epidemiology can by found in a chapter by Zahner and colleagues (1995). Here we focus selectively on the factors that are sometimes neglected in the design of studies in the general population. Most first-generation mental health surveys were typically small, based in a local community, and carried out by a small academic team. The past two decades have seen the emergence of adequately powered, large sample size surveys using complex, often clustered sampling methods, systematically developed and tested structured instruments, and specialized ‘survey’ methods of analysis, carried out by collaborations between professional survey organizations and academic researchers, which are referred to in examples that follow.

Cross-Sectional Surveys

This research paper refers mainly to the use of cross-sectional and longitudinal designs. Great attention is paid in such surveys to ensuring the representativeness of subjects so that inferences are generalizable and can be used, for example, at a national level and sometimes in small area statistics. Because we regard this as a fundamental issue, which is often inadequately handled in surveys other than those carried out by large (generic) survey organizations, we give this particular emphasis here.

The approach taken by one of us to the challenge of sampling children nationally illustrates some of the factors that can and need to be considered. Several methods of obtaining a representative sample of children in Great Britain were considered: carrying out a postal sift of the general population to identify households with children, sampling through schools, using administrative databases, and piggybacking on other surveys. It was decided to draw the sample from administrative records, specifically, the Child Benefit Records held by the Child Benefit Centre (CBC). Parents of each child under 16 living in the United Kingdom are entitled to receive child benefits unless the child is under the care of social services. Using these centralized records as a sampling frame was preferred to carrying out a postal sift of over 100 000 addresses or sampling through schools. The postal sift would have been time consuming and expensive. The designers did not want to sample through schools because they wanted the initial contact to be with parents who then would give signed consent to approach the child’s teacher. A two-hour survey was regarded as too long for piggybacking on other surveys.

Use of centralized records (see later also) does have some disadvantages; access to the records can be problematic and the frame may not be accurate or comprehensive. It was realized that some child benefit records did not have postal codes attributed to addresses: 10% in a first survey and 5% in the repeat. The Child Benefit Centre had no evidence that records with postal codes were different from those without. The addresses with missing postal codes probably represent a mixture of people who did not know their postal code at the time of applying for child benefits and those who simply forgot to enter the details on the form. If there are other factors which differentiate between households with and without postal-coded addresses, the key question is to what extent these factors are related to the mental health of children. Because these factors are unknown, one does not know what biases may have been introduced into the survey by omitting the addresses without postal codes.

The survey design dealt with the problem of omission of children in the care of social services by carrying out a separate survey of this vulnerable group even though such children represent only 0.5% of the population in England. Previous research had indicated high rates of mental disorders among this group. Also excluded from the original sample were cases in which ‘action’ was being invoked, such as occur with the death of the child or a change of address. These are administrative actions as distinct from some legal process concerning the child and hence should not bias the sample in any way.

Small-area statistical estimates are population approximations developed by specialized statistical procedures such as spatial interpolation. They allow policymakers, local planners, and individual users of services to extrapolate census and survey data to specific local areas. Very large survey sample sizes may be used in conjunction with census data allowing linkages between different information sources on economics, health, crime, quality of the environment, and so forth. The estimates obtained may be subject to census (or survey) or modeling error. Trend estimates may not be directly comparable from year to year because of changes in boundaries, data, and methodology. Estimates can be improved by the use of spatially more precise, geographically coded, building identifiers. Alternatively postal code data or an equivalent coding system are essential but will not be available in all parts of the world.

Screening And Full Assessment

Although in the children survey example all respondents were administered the same set of questions, many surveys employed two-stage or multiphase survey designs. The first stage consists of a self-report questionnaire administered to the full sample by lay interviewers who do not need to have any clinical training. In a second stage, a randomly selected subsample will undergo a more complex and detailed assessment, possibly involving some degree of clinical expertise. The second phase might involve a full clinical assessment of one or more forms of mental disorder, analogous to a second stage of a population dietary survey in which a random subsample of first stage respondents undergoes a more detailed inventory of all food kept in a household, and of food purchases within a past number of days, which may be carried out by a smaller team of research dieticians.

There are considerable advantages and also disadvantages to both the single and two-phase designs; these are well discussed in the literature (Newman et al., 1990; Shrout and Newman, 1989). The advantages of the single stage approach are as follows:

- Detailed information is collected on all respondents. A sample distribution can be produced on all subscales even though only those with an above-threshold score will have psychopathology.

- With the possibility of a longitudinal element in the survey, there is a large pool of respondents from which to select controls who could be matched on several characteristics to the children who exhibit significant psychiatric symptoms during the first-stage interview.

- A one-phase design is likely to increase the overall response rate compared with a two-phase (screening plus clinical assessment) design.

- A one-stage design reduces the burden put on respondents. Ideally, a two-phase design would require a screening questionnaire to be followed up with an assessment interview administered to the selected respondent. A one-stage design only requires one interview.

One of the advantages of a one-phase over a two-phase design is that it can be carried out in a far shorter time scale. The main disadvantage of a one-stage design is cost. The administration is far cheaper in two-stage designs, although they are likely to have more biases and less precision.

Cohort And Longitudinal Surveys

Cross sectional surveys explore associations between two variables (x and y) whereas prospective surveys allow the researcher to investigate the problem of unknown direction of causality (x → y; x←y; x ↔ y). In relation to mental disorder they can also provide invaluable information on the persistence and duration of mental disorder over time in the population (in general the commoner and less severe forms of disorder in adulthood tend to be of short duration rather than long lasting). However, they are not appropriate for examining treatment and service effectiveness prospectively because, if anything, at a given time, those having treatment are likely to be more severely ill and to have a poorer subsequent health outcome.

In our experience the more common obstacle to successfully carrying out a longitudinal study is a failure to include this element in the design from the beginning of the study, a ‘keeping in touch component.’ This is essential if the number followed up successfully is to be maximized. In an adequately funded ‘keeping in touch’ program, respondents are regularly sent reminders and updates, often including personal birthday greetings, on the progress and successful achievement of the study, thus sustaining what can be a considerable commitment on the part of respondents. This of course requires sustained funding over much longer periods some of which could be used to provide incentives.

Informed Consent

According to Martin (2000), the validity of survey research depends crucially on obtaining as high response rates as possible from the sample selected for a survey. However, individuals selected have a right to make an informed decision about whether or not to participate. Martin argues that without personal contact with an interviewer, the conditions needed to obtain informed consent cannot be achieved. Use of opt-out procedures based on a letter (and opt-in procedures to an even great extent) guarantees neither that the information needed to ensure that consent is informed reaches the right person nor that the person has read and fully understood what participation entails. Martin has concluded that truly informed consent can be obtained only if it is sought by an interviewer trained to explain the survey fully and answer all questions. This is analogous to a personal approach to take part in a clinical trial in which informed consent must also be obtained.

The survey research literature and standard survey practice both emphasize the importance of motivating people to agree to take part in surveys by stressing the importance of the survey and of their personal contribution. There is no evidence that such motivation is seen as exerting undue pressure. The voluntary nature of surveys is always explained, and respondents are free to refuse to answer particular questions or to terminate their participation at any stage. Additional safeguards in the case of the longitudinal and panel surveys are that explicit permission is sought to continue at each stage of the survey, so initial consent does not imply consent to every part of the survey process (Martin, 2000).

Case Control Studies

Measures of exposure status can be compared in which disease status is determined at the time of subject selection. This design may be useful in studying rare conditions, events, or exposures. However, unless these are obtained in the same population setting from which controls are drawn, comparisons and resulting estimates may be biased. This design is rarely used in this field.

Information Sources

Types of information sources can be divided into administrative and survey or census. Some very useful studies can be performed by means of existing well-collected administrative data, thus avoiding the high cost of new data collection and using those resources instead for the important tasks of analysis and dissemination.

Administrative Sources

For cultural and legal reasons, administrative authorities will probably have the best data on causes of death such as suicide and homicide. Data can exist in registers of independent organizations, provider services, or of the authority organization itself.

Censuses

Censuses are a similar source of data; the main advantage is that they collect whole-population data. But census sources are limited by the fact that questions on health are rare and virtually unheard of in relation to psychological and mental health. Other disadvantages are that they are carried out relatively infrequently, rely on proxy information (provided by one household member), and rely on another service such as the postal service to convey data.

Surveys

Surveys can be an efficient and relatively low-cost method for obtaining large numbers of observations in a systematic, reliable way and provide powerful methods for addressing questions on health. Such survey data sets are increasingly archived after a period of time and therefore remain available to the wider research community and to policy advisers (see the Relevant Websites section at the end of this research paper). This is good in that better use is made of such data at little extra cost, but it can have bad effects also, particularly in a complex area such as mental health, unless the original survey designers can contribute the analysis and interpretation of the data in order to obviate serious misunderstandings.

Mental Health Surveys

Early mental health surveys tended to be carried out on small samples obtained in single communities and were typically conducted by an individual or small academic team. Estimates from these studies carried little precision, and only substantial effects were demonstrable. Large-scale, statistically more powerful, survey methodologies began to impinge on the field of psychiatric surveys with the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Survey of Mental Disorders (ECA) (Robins et al., 1984), British National Psychiatric Morbidity Surveys ( Jenkins et al., 1997) (see Relevant Websites), the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) (Kessler et al., 1994), and now the WHO World Mental Health Survey (Demyttenaere et al., 2004), all of which have served to transform the field. Not only did this development herald the introduction of new instruments for assessing mental disorders (see below) but it also served to refine sampling and statistical methods used to generate scientific and policy information. Such surveys have probably been more successful in answering questions about effects within subgroups of the population such as those who are economically disadvantaged. They have also been effective in collecting representative data from difficult-to-reach populations, including low-income populations in less economically developed parts of the world. General health surveys and social and economic surveys have also made increased use of measures of mental and physical health and functioning, thus bringing evidence to a much wider community of policymakers and decision makers.

Registers

Disease and service registers have also played a key part, although few countries have been willing to or capable of operating these over sustained periods. Scandinavian countries, most notably Denmark, have made a contribution in this regard to studying, for example, rarer conditions such as bipolar disorder and other specific forms of psychosis within a whole population context. External researchers have also been able to work collaboratively with those responsible for maintaining such registers. The use of such sources must include a careful consideration of the quality of the register’s coding of data.

Services

Although services ought to be able to provide information on rarer events and conditions in practice, for example, we have found such sources to be unable to furnish reliable information except, of course, when they are linked to a register that is managed to high scientific standards. A key issue that may underlie this situation is that the purposes for which data are collected and used by a service are likely to be very different from those of scientific or policy researchers. Services may be able to supply information on the use of such services, providing diagnostic coded data (sometimes in close accord with an accepted set of definitions).

Record Linkage

Linking data on respondents or service users across population care sectors and agencies can be of value in ensuring continuity of care, evaluation, and planning of mental health services, depending of course on the aforementioned issue of data quality. Notable research examples have involved linking data on suicide with data on previous service usage. Useful recent examples of the use of record linkage to support services are the Ontario Data Linkage System (Squire et al., 2002) and the Western Australia Linked Database system (Holman et al., 1999).

Measurement Methods

As discussed earlier, we make a distinction in this section between measures suitable for clinical settings and requiring some clinical experience and measures that can be either self-completed or administered by a lay interviewer that are not only less costly to use but are also more feasible to use in the kinds of large-scale general population surveys needed to obtain information that is useful in planning and policy development. Further background reading about these kinds of measures can also be obtained elsewhere (Thompson, 1988; Biemer et al., 1991; Farmer et al., 2002).

Unstructured Methods

When an investigator is beginning to study a new area of research or is beginning to study an understood construct but in a new population or cultural context or setting, it may be prudent to start with qualitative assessments as a first stage in identifying key themes and concepts and in particular the language in which they are expressed.

Once a structured (or semistructured) instrument has been drafted, testing can be enhanced by means of cognitive interviewing (Biemer et al., 1991). After the test respondent answers each question, an interviewer then asks the respondent questions such as: What do you think was meant by that question? What were you thinking when you answered that question? Why did you answer it that way?

Qualitative analytical methods are used to summarize key points emerging from such interviews; questions are revised and further testing is carried out, and so on.

The more structured methods of measurement described further on were developed because of concerns about the use of unstructured measures such as the clinician mental state assessment. Given the all-important consideration of instrument reliability, mentioned previously, we do not propose to give further consideration to unstructured approaches to the assessment of mental health functioning.

Structured Measures

Fully structured measures are completed by study respondents. They can be either directly completed in the form of self-completion, ‘paper and pencil’ questionnaires although such methods are increasingly computer assisted; (see the Procedures section) or they can be administered face-to-face by a lay interviewer. When an interviewer administers a questionnaire, the interviewer must not impose her or his judgment on the responses to the questionnaire, which must be chosen by the respondent or left blank, unfilled. Considerable ingenuity has gone into the development of such questionnaires in order to gather information on the criteria needed to determine the presence of specified types of psychiatric disorder. Such techniques were first developed within the social survey field in order to collect information on complex social and economic issues. The principles involved began to be used in the field of mental disorders in the 1970s and 1980s. A strength but also a limitation of such interviewer-administered questionnaires is the use of branching rules: when a respondent states that they do not have a particular characteristic (e.g., symptoms of depression in general, being currently unemployed) further questions about depression or about the effects of being unemployed need not be asked. Such methods allow a great deal of information to be collected selectively but are limited by the sensitivity and specificity and positive and negative predictive value of the initial ‘screening’ or ‘sifting’ questions.

Self-Report Questionnaires

Self-report questionnaire can be used at little cost because interviewers need not be directly involved in their administration. A comprehensive listing of such questionnaires can be found in Farmer et al. (2002), where rating scales are also described. The best-known examples of such self-report measures for adults are the General Health Questionnaire (Goldberg, 1972), the Short-Form Questionnaire (Ware, 1993), which also assesses physical aspects of health and functioning, and the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire for children (Goodman et al., 2000b). These measures have been used in a considerable number of large-scale surveys (including prospective or panel studies), which mainly focus on general health rather than specifically on mental disorder. Also widely used is the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale to screen for perinatal maternal depression (Cox et al., 1987). A promising new measure recommended for identifying more severe forms of mental disorder are the new K6 and K10 Scales (Kessler et al., 2003). A great deal of attention has focused on the psychometric properties of these measures. Unfortunately, their deceptively simple appearance may disguise the enormous work that goes into their development. Therefore, researchers should be very cautious in trying to develop measures of their own, because questionnaire design and development is a highly specialized undertaking.

Structured Diagnostic Interviews

As already explained, diagnostic interviews extend the concept of self-report further; they either require an interviewer or, in some studies, a computer to administer the interview directly (interviewers will typically also use a computer rather than printed paper to help them correctly follow branching rules). Comprehensive listings are provided by Farmer et al. (2002). The limitations of these useful and efficient interview branching techniques need to be considered. For example, a respondent, perhaps for reasons of social desirability, may deny having symptoms of depression based on stem questions, which might otherwise have been picked up if nonstem questions (for example, about the physical effects of depression and accompanying thoughts) were asked in a nonbranching questionnaire. Therefore, some researchers prefer to use the self-report questionnaire formats that do not include any branching structure.

The first widely used such interview was the Diagnostic Interview Schedule, which later evolved into a series of interviews that carry the common title Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (Robins et al., 1988). Although lengthy and highly detailed, this quality has not been detrimental to their widespread use, including in the collection of survey data in low-income countries. However, they are not suitable for measuring severe mental disorders, and there are many different versions of the CIDI, thus limiting comparison between different studies. Less known are similar diagnostic interviews used in the British National Survey Programme (see Relevant Websites). For the child surveys, worth mentioning is a particularly novel solution to the challenge to combine fully structured questions and the use of clinical ratings in the Development and Well-Being Assessment (DAWBA) (Goodman et al., 2000a). The questionnaire used structured interviewing supplemented by open-ended questions. When definite symptoms were identified by the structured questions, interviewers used open-ended questions and supplementary prompts to get parents to describe the child’s’ problems in their own words. The wording of the prompts was specified. Answers to the open-ended questions and any other respondent comments were transcribed verbatim by the interviewers but were not rated by them. Interviewers were also given the opportunity to make additional comments, where appropriate, on the respondents’ understanding and motivation.

A small team of experienced clinicians reviewed the transcripts and interviewers’ comments to ensure that the answers to structured questions were not misleading. The same clinical reviewers could also consider clashes of information between different informants, deciding which account to prioritize. Furthermore, children with clinically relevant problems that did not quite meet the operationalized diagnostic criteria could be assigned suitable diagnoses by the clinical raters. There are no other existing diagnostic tools that combine the advantages of structured and semistructured assessments in this way, which is why a new set of measures were specifically designed for this survey. The new measures and their validity are described in more detail elsewhere (Goodman et al., 2000a).

Semistructured

The term ‘semistructured’ is used to refer to measures that could be considered as lying in between the preworded, fully structured measures and largely unstructured qualitative interviews just described. In the sense that it is used here, ‘semistructured’ refers to a style of interviewing that is flexible and more conversational but critically different in that the interviewer (either the interviewer or others on the research team) has two additional responsibilities: first, the selective framing of supplementary questions in order to add clarification and to respond to the way subjects at first answer and appear to understand questions; and second, sifting through the interview content and deciding on the final ratings. Issues of feasibility, cost, and complexity of the phenomena to be measured will bear on the choice of which approach to use in a study, as discussed earlier.

Diagnostic Interviews

Diagnostic interviews are discussed in detail elsewhere (Farmer et al., 2002; Thompson, 1988). As for fully structured diagnostic interviews, all the information needed for the mental disorder classification system is sought (and these interviews also use branching techniques). Because the interviewer is required to provide the judgment of each rating in a semistructured interview as compared to the respondent in a fully structured interview, great care is needed to ensure the consistency of such ratings between interviewers and across time within one study not to mention between studies. Little is known about how successful such efforts are. There is little doubt that such approaches will be very costly in most settings. However, in low-income populations the cost of interviews also may be lower; there may also be advantages arising from the flexible ‘clinical’ conversational style of such interviews that could serve to minimize misunderstanding among respondents who are perhaps less well acquainted with Western psychological terms. However, these are all conjectural matters for further investigation. Some of the issues are also discussed elsewhere in the wider context of survey measures in general (Biemer et al., 1991).

In a previous section we discussed the DAWBA (Goodman et al., 2000a), which combines a fully structured and a partial semistructured element that has been shown to be reliable in generating DSM-IV and ICD-10 categories. The most widely used such measure in adult mental health surveys is the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM (SCID) (Spitzer et al., 1992). Also used, particularly to elucidate psychotic forms of disorder, is the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN) (World Health Organization Division of Mental Health, 1992). Both should be administered by clinically experienced, specifically trained clinicians or by interviewers with greatly extended training that provides such experience (Brugha et al., 1999). The SCAN provides dimensional and ICD-10 and DSM-IV diagnostic outputs and has been translated extensively; the SCID-I provides DSM-IV outputs only and also exists in a number of translated forms.

Rating Scales

Rating scales are similar to semistructured interviews in that the person administering the scale judges the ratings. However, far less guidance is provided on how to collect the data. Such measures were developed in order to efficiently make use of the observations of a clinician, who presumably would already have conducted a mental state assessment, in treating a patient. These approaches have for many years been in widespread use in clinical treatment trials but are rarely used in surveys. Examples can be found in Farmer et al. (2002) and Thompson (1988).

Cross-Population Issues

A number of references have been made to considerations that are of importance when measuring mental health in different cultures and language settings. This principle should be extended to consideration of any subpopulation that could be marginalized or excluded, such as prisoners (Brugha et al., 2004) and those with sensory impairment. For example, a version of the DIS interview has been developed for deaf people (Montoya et al., 2004).

Culture And Ethnicity

There is a large body of evidence suggesting that the idioms for mental distress vary across different ethnic groups (Sproston and Nazroo, 2002). The implication of possible cultural differences in symptomatic experience is that standardized research instruments will perform inconsistently across different ethnic groups, greatly restricting the validity of conclusions based on their use in surveys. Although there is some evidence of the universality of the major forms of clinical psychopathology (Cheng et al., 2000), this is not universally accepted. Fundamental issues about the transferability of Western psychological and psychopathological concepts continue to be debated. Invaluable experience of the practicalities and scope for addressing such challenges has come from the International Pilot Studies of Schizophrenia and subsequent research under WHO auspices (Jablensky et al., 1992) and from recent work within the general population survey paradigm of the diverse cultures and languages found in urban Britain (Sproston and Nazroo, 2002), which included detailed qualitative, unstructured assessments carried out in the first language of respondents.

Translation Methods And Protocols

A great deal of experience has been built up in translating (Sartorius, 1998) and testing instruments in different population and cultural settings. Great emphasis has been placed on the use of both forward and back-translation. Recent developments emphasize that it is the concepts rather than the words that need to be translated, thus preserving meaning as far as possible. In order for questions to be understood in a way that is comparable within and across populations that rely on different languages and dialects, it is necessary to have a translation procedure that yields equivalent versions of the questions across a variety of settings and cultures.

There are three main problems that occur when trying to standardize the translation process across countries:

- linguistic differences caused by changes in the meaning of words between dialects;

- translation difficulties; and

- differences that arise when applying a concept across cultures.

The conceptual translational method relies on detailed explanations of the terms used in each survey question, as well as the underlying concepts that the questions were intended to measure. This approach differs from the forward-backward method in the ‘backward’ step, during which rather than translating the question back into the original language, a checker determines whether each question was properly translated such that the intended concepts were actually captured (Robine and Jagger, 2002; Robine and Jagger, 2003).

Measurement Of Specific Disorders

As mentioned earlier, mental health survey approaches and programs in a given geographic setting sometimes begin by assessing an overall or ‘common mental disorder’ outcome that may be dimensional (see Figure 1) or based on a categorical case definition. This approach can also be embedded into surveys that assess other aspects of health, economic and social functioning. The influence of clinical psychiatry has led to an expectation of data on specific categories of mental disorder. Most surveys have focused on more common internalizing disorders: anxiety and depression in adults, conduct and emotional disorders in children and young people. Many surveys also attempt to measure rarer and more complex disorders (in terms of diagnostic criteria and their measurement), such as obsessive compulsive disorder and psychosis in adults and attention deficit disorder and developmental disorders in children (e.g., tick disorder and autism). Externalizing disorders involving the use of substances and alcohol are also often assessed; other disorders of behavior, such as personality disorder, are rarely assessed. These expectations are likely to be increasingly questioned in favor of the more practical and parsimonious value of information on severity, complexity per se, and persistence over time.

Procedures (Surveys Mainly)

The procedures used in surveys also determine quality, cost, and acceptability. Quality (or accuracy) is the most difficult of these to evaluate. A notable example is that it has been shown that audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) administration can yield more information on mental health than that obtained from an interviewer-administered, paper-and-pencil (I-PAPI) mental health module of the CIDI (Epstein et al., 2001).

Face To Face

In face-to-face procedures the respondent is administered the questions by an interviewer who will typically visit the person’s home or other agreed-upon place. Although costly, such methods are regarded as of high quality. The researcher has control over the quality of the training and procedures used by interviewers.

Postal

Respondents complete and return a questionnaire by post, usually using a prepaid cover or envelope. Unless additional steps are taken to ensure cooperation, response rates tend to be so low as to make the information provided of limited value, but methods for increasing response rates have been developed. Costs are understandably very low. It may come as a surprise, however, to find that quality can be high, possibly because respondents have time to think more carefully about questions and also because social desirability factors play less of a part (Bushery et al., 1996) than in face-to-face interviews. However, self-completion methods that are fully anonymous are now often included within a face-to-face interview procedure.

Electronic And Digital

Various electronic methods have gradually been introduced; some of these are under active development and likely to become either more sophisticated or drop out of use. In most contexts and cases, costs are lower than for the equivalent interviewer-based approach, although start-up costs may be very high.

Procedures include computer-assisted telephone interviewing, the Internet, interactive voice response over telephone (IVR), and so forth. IVR is a more automated version of telephone interviewing but may be limited by the proportion of the population who subscribe. Telephone interviewing is used widely by commercial organizations in some populations, and this may lead to resistance among some of the public and thus compromise the representativeness of survey findings.

Start-up costs for Internet surveys, although dropping, are still high but then fall to almost zero per unit cost. They may share some of the advantages of accuracy of postal methods. Data can be collected from all over the world (which may be either an advantage or a disadvantage) and is immediately available for analysis. Other computer-administered methods include audio computer-assisted interviewing (ACASI), in which the respondent may wear ear phones; text to speech (TTS), which may use ‘talking heads’ (Avatars) that can be specifically gender and culture matched to the respondent; digital recording; and touch screen responses to questions.

Computer adaptive testing (CAT), in which the software calculates and determines the next question to ask in an interview, is probably limited to assessing fairly simple concepts and facts rather than attitudes; when we evaluated such a system in a comparison with a clinical evaluation of neurotic symptoms we found poor agreement (Brugha et al., 1996).

Application Of Measurement Methods In Public Health Contexts (E.G. Surveillance And Screening In Health Settings)

Government policy documents are beginning to suggest the use of surveillance methods such as repeat surveys over time in order to evaluate policies and success in implementing health objectives (e.g., England; Department of Health, 1999). National mental health strategies should set realistic targets for improvements in the mental health of the population ( Jenkins et al., 2002). The example of a common mental disorder for which there is a range of effective treatments deserves mention. Despite the high prevalence rates of common mental disorders, they have traditionally been underdetected and undertreated. In recent years changes in services should have improved this situation in Great Britain. A campaign by the Royal Colleges of General Practitioners and of Psychiatrists to increase awareness and the effective treatment of depression led to over half of general practitioners (GPs) taking part in teaching sessions on depression. The pharmaceutical industry successfully encouraged increased prescription of newer antidepressants. The effectiveness of such innovations may be evaluated by monitoring the mental health and treatment of representative samples of the whole population surveyed in 1993 and 2000. However, a recent examination of rates of such disorders in 1993 and 2000, during which rates of treatment increased dramatically, concluded that treatment with psychotropic medication alone is unlikely to improve the overall mental health of the population nationally (Brugha et al., 2005). Similar conclusions have emerged since from the USA (Kessler et al., 2005). Such evidence can be interpreted as pointing to the need to develop effective prevention policies for which surveillance methods would also be essential.

Policy Information And Decision Making

Little is known or understood about how policymakers use information from mental health surveys. Expectations are likely to be shaped by the nature and value of information used in physical health and evidence-based treatments and services, including prevention policies. This may be why information on the prevalence of mental disorders is often sought and provided, although the concept may have little meaning. A surprisingly large number of systematic reviews, often including the use of synthetic methods such as meta-analysis, have appeared in the psychiatric epidemiology literature in the past decade. Policymakers require guidance on the value of such reviews, given the technical difficulties faced in carrying out good-quality studies in this field.

Conclusions

Methods for measuring psychiatric and related psychological disorders and outcomes in populations have advanced considerably, particularly in the past two decades. Some long-standing assumptions have been tested, sometimes with surprising conclusions. Contemporary researchers pay particular attention to consistency and reproducibility of findings, in contrast to an earlier era in which clinical applicability often dominated the choice of the method used. Studies have become much larger and require the input of many more and different disciplines than in the past; this is probably to the good, as it may help render the topic of mental disorder more acceptable and less stigmatizing. Although the field seems new and technologically exciting, old principles are still important: simplicity and clarity of purpose, an appropriate design, the use of well-tested measures, and the interpretation of findings with a clear understanding of the limitations of the methods used. The measurement of mental disorder now stands equal in importance, in methodological rigor and usefulness, to other major public health topics.

Bibliography:

- American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

- Biemer P, Groves RM, Lyberg LE, Mathiowetz NA, and Sudman S (1991) Measurement Errors in Surveys. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Brugha TS (2002) The end of the beginning: A requiem for the categorisation of mental disorder? Psychological Medicine 32(7): 1149–1154.

- Brugha TS, Teather D, Wills KM, Kaul A, and Dignon A (1996) Present state examination by microcomputer: Objectives and experience of preliminary steps. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 6: 143–151.

- Brugha TS, Nienhuis FJ, Bagchi D, Smith J, and Meltzer H (1999) The survey form of SCAN: The feasibility of using experienced lay survey interviewers to administer a semi-structured systematic clinical assessment of psychotic and non-psychotic disorders. Psychological Medicine 29(3): 703–712.

- Brugha TS, Bebbington PE, Singleton N, et al. (2004) Trends in service use and treatment for mental disorders in adults throughout Great Britain. The British Journal of Psychiatry 185: 378–384.

- Brugha T, Singleton N, Meltzer H, et al. (2005) Psychosis in the community and in prisons: A report from the British National Survey of Psychiatric Morbidity. American Journal of Psychiatry 162(4): 774–780.

- Cheng ATA, Tien AY, Brugha TS, et al. (2000) Cross-cultural implementation of a Chinese version of the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN) in Taiwan. British Journal of Psychiatry 178: 567–572.

- Cox JL, Holden JM, and Sagovsky R (1987) Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10 item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. British Journal of Psychiatry 150: 782–786.

- Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, et al. (2004) Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Journal of the American Medical Association 291(21): 2581–2590.

- Department of Health (1999) National Service Frameworks for Mental Health. Modern Standards and Service Models, pp. 149. London: Department of Health.

- Epstein JF, Barker PR, and Kroutil LA (2001) Mode Effects in Self-Reported Mental Health Data. Public Opinion Quarterly 65(4): 529–549.

- Farmer A, McGuffin P, and Williams J (2002) Measuring Psychopathology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Goldberg DP (1972) The Detection of Psychiatric Illness by Questionnaire. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Goodman R, Ford T, Richards H, Gatward R, and Meltzer H (2000a) The Development and Well-Being Assessment: Description and initial validation of an integrated assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, JID 0375361, 41(5): 645–655.

- Goodman R, Ford T, Simmons H, Gatward R, and Meltzer H (2000b) Using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) to screen for child psychiatric disorders in a community sample. British Journal of Psychiatry, JID 0342367, 177: 534–539.

- Green H, McGinnity A, Meltzer H, Ford T, and Goodman R (2005) Mental Health of Children and Young People in Great Britain, 2004. Hampshire, UK: Palgrave McMillan.

- Holman CD, Bass AJ, Rouse IL, and Hobbs MS (1999) Population-based linkage of health records in Western Australia: Development of a health services research linked database. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 23(5): 453–459.

- Jablensky A, Sartorius N, Ernberg G, et al. (1992) Schizophrenia: Manifestations, incidence and course in different cultures. A World Health Organization ten-country study [published erratum appears in Psychological Medicine Monograph Suppl. 1992, Nov. 22(4): following 1092]. Psychological Medicine Monograph Supplement 20: 1–97.

- Jenkins R, Bebbington P, Brugha T, et al. (1997) The national psychiatric morbidity surveys of Great Britain – Strategy and methods. Psychological Medicine 27(4): 765–774.

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. (1994) Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 51(1): 8–19.

- Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, et al. (2003) Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry 60(2): 184–189.

- Kessler RC, Demler O, Frank RG, et al. (2005) Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. The New England Journal of Medicine 352(24): 2515–2523.

- MacArthur C, Winter HR, Bick DE, et al. (2002) Effects of redesigned community postnatal care on women’s’ health 4 months after birth: A cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet 359(9304): 378–385.

- Martin J, Social Survey Division, ONF (ed.) (2000) Informed Consent in the Context of Survey Research. London: Office for National Statistics.

- Montoya LA, Egnatovich R, Eckhardt E, et al. (2004) Translation Challenges and Strategies: The ASL Translation of a Computer-Based Psychiatric Diagnostic Interview 4(4): 314–344.

- Newman SC, Shrout PE, and Bland RC (1990) The efficiency of two-phase designs in prevalence surveys of mental disorders [published erratum appears in Psychological Medicine 1990, Aug. 20(3): following 745]. Psychological Medicine 20(1): 183–193.

- Robine JM and Jagger C (2003) Creating a coherent set of indicators to monitor health across Europe: The Euro-REVES 2 project. European Journal of Public Health 13(3 Suppl): 6–14.

- Robine JM and Jagger C (eds.) Euro-REVES (2002) Report to Eurostat on European Health Status Module. Geneva, Switzerland: EUROSTAT.

- Robins LE, Helzer JE, Weissman MM, et al. (1984) Lifetime prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders in three sites. Archives of General Psychiatry 41: 949–957.

- Robins LN, Wing J, Wittchen HU, et al. (1988) The Composite International Diagnostic Interview. An epidemiologic instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different diagnostic systems and in different cultures. Archives of General Psychiatry 45(12): 1069–1077.

- Sartorius N (1998) SCAN translation. In: Wing JK and Ustu¨ n TB (eds.) Diagnosis and Clinical Measurement in Psychiatry. A Reference Manual for SCAN/PSE-10, pp. 44–57. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Shrout PE and Newman SC (1989) Design of two-phase prevalence surveys of rare disorders. Biometrics 45(2): 549–555.

- Singleton N, Bumpstead R, O’Brien M, Lee A, and Meltzer H, National Statistics (eds.) (2001) Psychiatric Morbidity among Adults Living in Private Households, pp. 154. London: The Stationary Office.

- Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, and First MB (1992) The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). I: History, rationale, and description. Archives of General Psychiatry 49(8): 624–629.

- Sproston K and Nazroo JY (eds.) (2002) Ethnic Minority Psychiatric Illness Rates in the Community (EMPIRIC) – Quantitative Report, pp. 210. London: The Stationary Office.

- Squire L, Bedard M, Hegge L, and Polischuk V (2002) Current evaluation and future needs of a mental health data linkage system in a remote region: A Canadian experience. Journal of Behavioral Health Services Research 29(4): 476–480.

- Thompson C (1988) The Instruments of Psychiatric Research, 1st edn. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

- Ware JE (1993) SF-36 Health Survey. Boston, MA: Medical Outcomes Trust.

- Wing JK, Cooper J, and Sartorius N (1974) Measurement and Classification of Psychiatric Symptoms. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- World Health Organization (1992) ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (1993) The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Diagnostic Criteria for Research. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

- World Health Organization Division of Mental Health (1990) ICD-10, chapter 5, Mental and Behavioural Disorders (Including Disorders of Psychological Development): Diagnostic Criteria for Research (May 1990 Draft for Field Trials). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. (Distribution: limited).

- World Health Organization Division of Mental Health WHO SCAN Advisory Committee (ed.) (1992) SCAN Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry, Version 1.0, pp. 242. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Zahner GE, Chung-Cheng H, and Fleming JA (1995) Introduction to epidemiological research methods. In: Tsuang M, Tohen M, and Zahner GE (eds.) Textbook in Psychiatric Epidemiology, pp. 23–54. New York: Wiley.

- American Statistical Association (1996) How interview mode affects data reliability. Proceedings of the Survey Research Methods Section, American Statistical Association. Alexandria, VA: American Statistical Association.

- Biemer P, Groves RM, Lyberg LE, Mathiowetz NA, and Sudman S (1991) Measurement Errors in Surveys. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Farmer A, McGuffin P, and Williams J (2002) Measuring Psychopathology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Green H, McGinnity A, Meltzer H, Ford T, and Goodman R (2005) Mental Health of Children and Young People in Great Britain, 2004. Hampshire, UK: Palgrave McMillan.

- Shrout PE and Newman SC (1989) Design of two-phase prevalence surveys of rare disorders. Biometrics 45(2): 549–555.

- Singleton N, Bumpstead R, O’Brien M, Lee A, and Meltzer H (eds.) (2001) Psychiatric Morbidity Among Adults Living in Private Households, pp. 154. London: The Stationary Office National Statistics.

- Sproston K and Nazroo JY (2002) Ethnic Minority Psychiatric Illness Rates in the Community (EMPIRIC) – Quantitative Report, pp. 210. London: The Stationary Office.

- Thompson C (1988) The Instruments of Psychiatric Research, 1st edn. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- Wing JK, Cooper J, and Sartorius N (1974) Measurement and Classification of Psychiatric Symptoms. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- World Health Organization (1993) The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Diagnostic Criteria for Research. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

- Zahner GE, Chung-Cheng H, and Fleming JA (1995) Introduction to epidemiological research methods. In: Tsuang M, Tohen M, and Zahner GE (eds.) Textbook in Psychiatric Epidemiology, pp. 23–54. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.