This sample Menopause Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Introduction

One of the earliest references to menopause in the world literature comes from the Bible: ‘‘Abraham and Sarah were old and well stricken in age; and it ceased to be with Sarah after the manner of women’’ (Gen. 18:11), although three chapters later Sarah gives birth to Isaac, so in reality she could not have had her menopause at that time. In the whole of nature only the human female experiences a physical menopause. While other animals remain potentially fertile until death, the woman of today, in the developed parts of the world at least, will spend on average one-third of her life without the benefits of the female sex hormone – estrogen. By contrast, a man slides without abrupt change from one stage of his life to the next maintaining the ability to father children well into old age. The ovary is the only organ in the body that naturally ceases to function in midlife. For many reasons, however, women will readily appreciate the merit of not being fertile into old age, as the human child is more dependent on its mother than any other animal.

It is only relatively recently that menopause has attracted much attention. Indeed, at the beginning of the twentieth century a woman in the Western world could only expect to live to about 48 years, but now life expectancy is about 80 years, with the number of women in the United Kingdom aged over 85 years expected to rise by 50% in the next 20 years. The United Nations projects that by the year 2050 women aged 60 years and over will constitute 40% of the female population of Europe and 23% of the entire world. In comparison, in 1997, the life expectancy in sub-Saharan Africa was only 52 years and, in many African countries, life expectancy has decreased by 3 years as a result of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), so that menopause is less likely to be of much relevance for many women.

Menopause, or last menstrual period, is a natural biological event resulting from failure of the ovaries to continue producing eggs (ova) and the associated hormones estrogen and progesterone. The term is derived from the Greek menos, meaning month, and pausos, meaning an ending. The median age at which menopause occurs is 52 years and has changed little over the years. It tends to occur earlier in communities of low socioeconomic status, those living at high altitudes, and 1–2 years earlier in women who smoke. The timing of the natural menopause tends to be inherited, with daughters experiencing menopause around the same time as their mothers.

Types Of Menopause

Premature

A premature menopause occurs in about 1% of women, being defined as menopause before the age of 40 years. This may be due to genetic factors or be iatrogenic as a result of a medical or gynecological condition. The associated infertility can be very distressing when premature menopause occurs unexpectedly before intended pregnancies have been achieved.

Surgical

A surgical menopause occurs when functioning ovaries are removed, usually together with a hysterectomy (removal of the uterus). The sudden cessation of ovarian function and rapid decline in circulating estrogen is more likely to result in menopausal symptoms than a more gradual decrease in ovarian activity associated with a natural menopause.

Natural

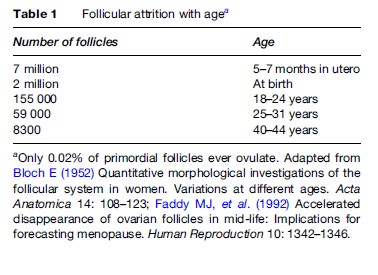

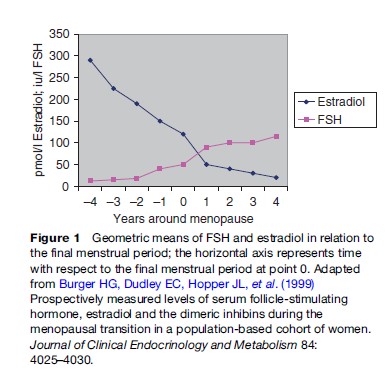

The mechanism of a natural menopause is not fully understood but is related to the ovaries running out of suitable follicles from which ova are produced. The ovaries have a finite number of follicles whose numbers are maximal during intrauterine life, after which there is a logarithmic reduction until about 50 years later when the stock is exhausted (Table 1), or those remaining are unable to respond to stimulation by endogenous or exogenous gonadotrophins. Prior to menopause and during a variable number of months or years there is a gradual reduction in the control mechanism for the ovarian cycle with accompanying endocrine changes (Burger et al., 2004). In particular, there is a decrease in the secretion of estradiol, the main estrogen, from the ovaries accompanied by a rise in circulating follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) as the pituitary gland tries to stimulate the increasingly resistant remaining ovarian follicles to develop (Figure 1). This loss of control of the cycle causes disturbances of menstruation with heavier, painful, irregular, and sometimes erratic periods that are frequent causes of medical consultation. In the majority of cases, there is no underlying disease process and the abnormal periods are labeled ‘dysfunctional uterine bleeding.’ However, benign conditions, such as uterine fibroids and endometriosis, are also more common at this time and may exacerbate such disturbances that can severely affect the quality of life.

The period of time encompassing the transition from normal regular menstrual cycles through menopause and into the postmenopause and postreproductive phase is called the climacteric – from the Greek meaning ‘a ladder.’ A woman is said to be postmenopausal when there has been a gap of 12 months without menstruation. This is mainly of medical significance, as any bleeding after this time is abnormal and requires investigation to exclude cancer of the endometrium (lining of the womb), which will be found in about 10% of women.

Effects Of Menopause

Menopause has different implications for women depending on their culture and tradition. In societies in which menstruating women are considered to be unclean and may thus be excluded from praying in public, the release from such inferior status allows them to assume an important and rewarding role in the family and society (in most Indian languages there is no word for menopause). In contrast, the modern, Western societal values and attitudes are more likely to emphasize the negative aspects, such as loss of femininity and sexual attractiveness. This time of life may also coincide with domestic changes such as children leaving home (empty nest syndrome), parents becoming aged and infirm, husband and wife at a stressful time in their careers, all of which may influence how a woman adjusts to the climacteric and menopause. It is therefore not without good reason that the phrase ‘change of life’ has often been applied to this time.

Symptoms

Aging in itself is accompanied by various inevitable physical changes and it can be difficult to distinguish which clinical symptoms are a result of the loss of ovarian function and estrogen, and which are due to the aging process itself. About 80% of Caucasian women will experience some symptoms considered to be due to estrogen deficiency during the climacteric. Hot flushes and sweats are the most common symptoms and of those experiencing a natural menopause 60–75% will be affected. In Japan, however, flushes are much less common and there is not even a word in the Japanese language for them. Cultural, genetic, and dietary factors with, in particular, the high intake of soy protein in the Japanese diet, which is rich in phytoestrogens, may contribute to the low prevalence of hot flushes in Japan. The Mayan Indian women in Mexico are said not to experience hot flushes at all.

The Hot Flush

The hot flush is a unique and disagreeable sensation of heat that can occur at any time of the day or night. It may be triggered by various situations such as sudden temperature change; drinking tea, coffee, or alcohol; eating spicy foods; or embarrassment, although in the latter it is definitely different from a blush. Commonly, the sensation starts in the face, neck, head, or chest and the initial focal point may be very specific, such as an earlobe, forehead, or between the breasts. Subsequent spread of the sensation of heat may be in any direction and some experience it all over the body. The frequency of flushing varies between individuals ranging from a few per month to several per hour, and similarly the duration may vary from a few seconds to one hour, although the mean is around 3 minutes (Sturdee et al., 1978). The more intense and severe flushing episodes may be followed by sweating, though some will also sweat without an apparent initial flush. When these disturbances occur at night, there is a resultant domino effect causing disturbed sleep, lethargy, poor concentration and irritability, all of which improve with successful treatment of the flushes. Hot flushes are commonly experienced for around 1 to 2 years but in 25% of women they may continue for more than 5 years and rarely for 25–40 years. Hot flushes can therefore have a very significant effect on quality of life and cause great embarrassment, especially in the workplace or socially. Although no one will ever die from a hot flush, the impact on general well-being and self-esteem should not be underestimated.

While men do not experience a comparable climacteric, following the uncommon situation of testicular failure or bilateral orchiectomy (removal of the testes), severe hot flushes and sweats may occur, which have similar features and associated physiological changes to those in women.

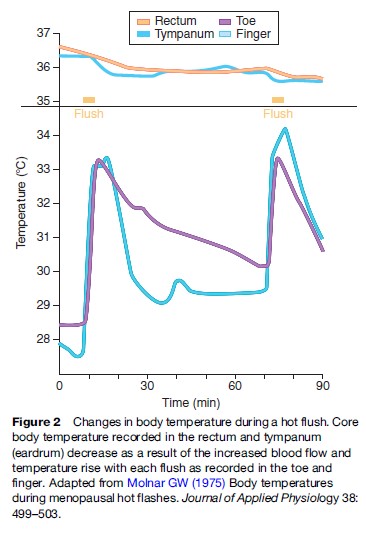

The mechanism of flushing is incompletely understood and difficult to investigate, but it involves a disturbance of the temperature-regulating center (thermostat) situated in the middle of the brain (Freedman, 2001). The decline in estrogen during the climacteric, and probably the fluctuating levels of estrogen in particular, alter the sensitivity of this center such that it initiates inappropriate mechanisms to reduce body temperature by suddenly increasing the blood flow to the skin, which produces the sensation of heat and causes sweating (Figure 2). These vasomotor disturbances, referring to regulation of peripheral blood vessel tone, are common in the years before and after menopause when estrogen levels are erratic but cease in later years when estrogen levels, although very low, have stabilized. Priming with estrogen seems to be an essential prerequisite for flushing, as young women with Turner’s syndrome (a condition in which the ovaries have not developed or are inactive) have very low circulating levels of estrogen, but do not have flushes. However, if these women are given estrogen replacement therapy, which is later stopped, hot flushes can occur and are often a very distressing, new problem. The link with estrogen is also evident in women being treated for breast cancer with tamoxifen, who often have distressing hot flushes due to the antiestrogenic actions of the drug also affecting the brain. There are complex neuroendocrine actions also involved in the temperature-regulating mechanism in which the hormone serotonin has a key role. Serotonin has many functions in the body including controlling mood and recently it has been found that drugs that are used for relieving depression can also suppress hot flushes, although not as effectively as estrogen replacement therapy.

Other Symptoms

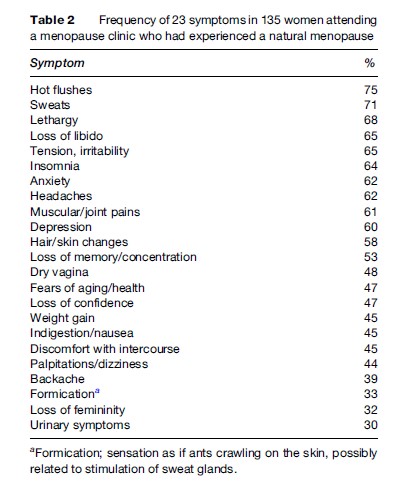

While the hot flush is the most characteristic symptom and experienced by most women, the prevalence of other symptoms that can be attributed to the decline in circulating estrogen is very variable and less easily determined. Women who have experienced severe premenstrual symptoms during the premenopausal years are more likely to suffer from symptoms during the climacteric. Many problems at this time are attributed to ‘the change’ (Table 2) but in reality the only genuine estrogen deficiency symptoms are:

- Hot flushes and sweats

- Vaginal dryness

- Disturbed sleep

- Poor memory/concentration

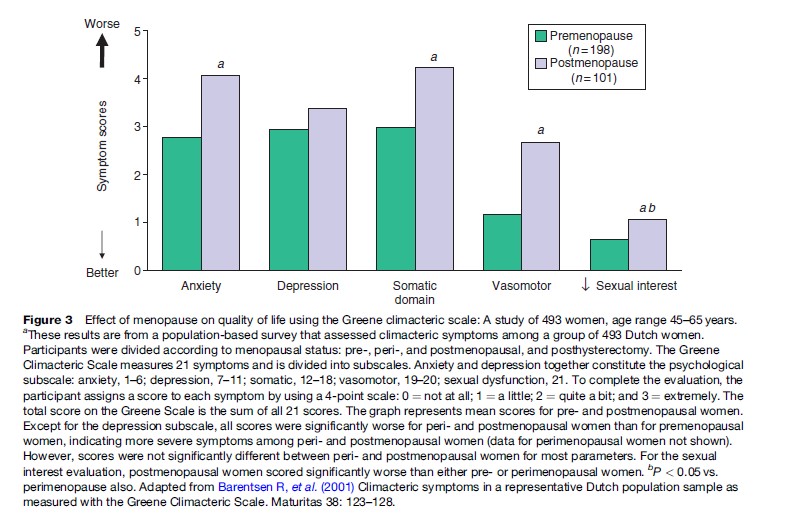

It is frequently thought that depression is more common in the climacteric, but the term has now been used to cover a wide variety of symptoms and degrees of illness. A depressed mood is a normal human emotion that everyone experiences at some time, and feelings of sadness and disappointment are part of normal life experience. Individual circumstances will influence whether the arrival of menopause is accompanied by psychological distress or, for some women, a feeling of relief and improved general well-being. For those who are depressed during menopause transition, the main predictors seem to be a history of depression, low socioeconomic status, stressful life events, and chronic ill health. Various rating scales and instruments have been used to evaluate the symptoms associated with menopause and estrogen deficiency. A study of women before and after menopause has shown significant differences in anxiety, somatic physical complaints, flushes and sweats (vasomotor symptoms), and sexual interest, but not in depression (Figure 3).

Women who have had a surgical menopause and those who hold negative beliefs about menopause, are more likely to become depressed. Moreover, psychosocial factors have been found to account for much more of the variation in psychological symptoms than stage of menopause (Hunter, 1996). Nevertheless, it remains possible that hormonal changes might influence mood for some women. Improvements in some psychological symptoms with estrogen therapy may just be due to a mental tonic effect of estrogen. It is well recognized that women will often state that they never felt so well as when they were pregnant, when the very high levels of circulating estrogen may be an important factor.

Libido

Loss of sexual desire may be reported by about 45% of postmenopausal women. Various physical factors related to aging in both men and women will affect both desire and performance, but vaginal dryness and atrophic changes due to estrogen deficiency can be a major factor that is easily corrected by estrogen replacement therapy, given either locally to the vagina or systemically. In men, sex drive is strongly correlated with testosterone, both being at their peak in men in their 20s. Women also produce testosterone and other androgens from their ovaries and adrenal glands. The reduction in ovarian function at menopause results in decreased testosterone levels. Women who have had their functioning ovaries surgically removed, resulting in a precipitous drop in both estrogen and testosterone, report a reduction in well-being, energy, and libido. These can be restored more effectively by therapy with a combination of estrogen and testosterone than by estrogen alone. However, the link between libido and testosterone in women is not as clear as might be expected. Measurement of circulating testosterone levels is generally unhelpful and in many women testosterone therapy does not help the libido, thus indicating that other factors are responsible.

Physical Effects

Urogenital Tract

Many tissues are sensitive to estrogen and will change as a result of the decrease in circulating estrogen levels. The urogenital tract is especially well endowed with estrogen receptors and the vaginal skin shows the most marked changes, which usually are evident a year or more after menopause. Estrogen deficiency causes gradual atrophy of the vagina and urinary tract. The earliest symptom is usually vaginal dryness, which may cause pain or discomfort during intercourse. Estrogen promotes a good blood supply to the vagina and stimulates glands in the cervix and at the entrance to the vagina to produce lubricating secretions. These secretions are fermented by lactobacillus bacteria in the vagina, and produce an acid environment, which protects against infection. Thus, in the absence of estrogen, the vagina becomes less acid and loses some resistance to infection. Itching of the vagina and vulva are also common.

Sexual activity has an impact on the health of the vagina. Comparisons of sexually active and abstinent postmenopausal women have shown less vaginal atrophy in those who are active, despite similar blood levels of estrogen in both groups (Bachmann et al., 1984). Estrogen also helps to maintain a healthy lining of the bladder and urethra and, as is the case with the vagina, lack of estrogen leads to an increase in urinary tract infections. Estrogen deficiency may also make the bladder muscle more irritable, which could explain why postmenopausal women can suffer from urge incontinence (overactive bladder). This is characterized by a very strong desire to empty the bladder, which may not be resisted causing incontinence. However, although a direct role of estrogen in this process has not been confirmed, urge incontinence is exacerbated by urinary infections, which are reduced by estrogen. The other common type of incontinence is stress incontinence, in which leakage results from a sudden rise in abdominal pressure, such as in coughing, sneezing, laughing, or exercising. Up to one-third of women over the age of 60 years suffer from this condition in which many factors are likely to be involved including the effects of previous childbirth, being overweight, smoking, age, and muscular weakness, but estrogen deficiency does not seem to be a significant factor.

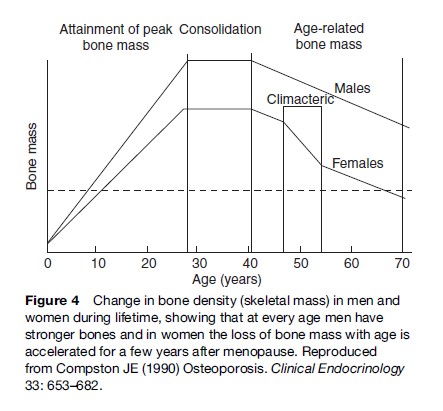

Bone

Bone density and strength change considerably over a lifetime, but especially in women, when after menopause there is an accelerated loss of bone density due to estrogen deficiency. In many women this will lead to osteoporosis, which is defined as a skeletal disorder characterized by compromised bone strength predisposing to an increased risk of fracture. In both sexes, bone density increases during adolescence reaching a peak around 30 years of age, which is sustained for some years and begins to decline during the mid-40s (Figure 4). After menopause, an accelerated period of bone loss occurs lasting for up to 10 years followed by a much slower rate of bone loss.

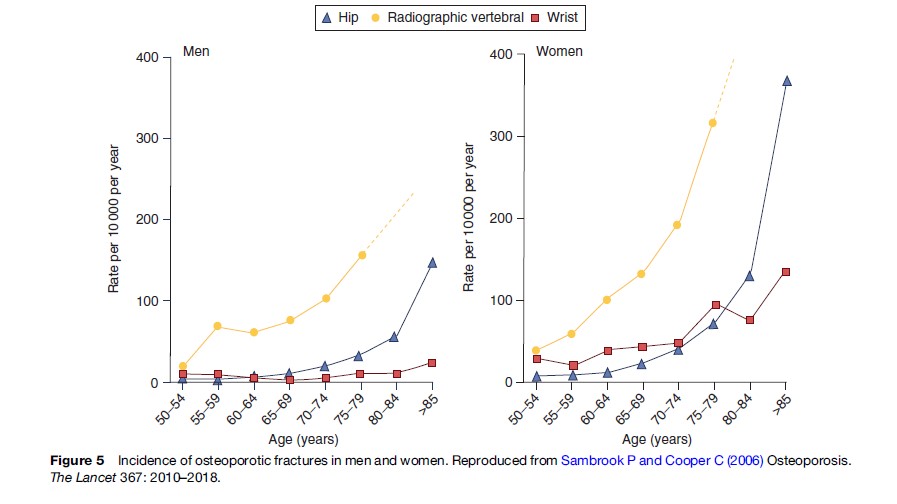

The risk of developing osteoporosis largely depends on the level of the peak bone mass as well as the rate of postmenopausal bone loss and longevity. Men generally develop osteoporosis only late in life because they start losing bone from a much higher peak bone mass and do not have the accelerated loss due to the sudden decrease in sex hormone production as occurs at menopause. By the age of 70 years, women have lost 50% of their skeleton while men lose only 25% by the age of 90 years. Without estrogen, female bone density typically decreases by about 2% per year in the spine and 1% per year in the hip, although in some women the loss is as much as 10 and 5%, respectively. Osteoporosis does not cause any symptoms until a fracture occurs, but every 10% loss of bone doubles the risk of fracture.

The different incidences of fractures in men and women with age are well recognized (Figure 5). Gradual loss of height with advancing years is part of the normal aging process but, in addition, the loss of bone in the vertebral bodies in women accelerates the process. In women with severe osteoporosis, repeated vertebral compression fractures may result in thoracic kyphosis, commonly known as a dowager’s hump. There is also some evidence that oral bone and attending tooth loss are associated with menopausal estrogen deficiency and osteoporosis (Lindsay et al., 2002).

The incidence of osteoporosis is high and is predicted to increase, constituting one of the most serious health problems currently faced by industrialized countries. Some statistics concerning osteoporosis fractures are the following:

- In the United States at least 1.3 million fractures per year are attributable to osteoporosis.

- In the United Kingdom the annual cost to the National Health Service is around UK£500 million.

- In some countries, 20% of hospital beds are occupied by people with hip fractures.

- One in four hip fracture patients needs long-term nursing care and one in three will never regain full independence.

Women with a premature menopause should be given hormone replacement therapy (HRT) at least until the normal age of menopause to avoid premature loss of bone. As well, prevention of osteoporosis should start in early life by encouraging young women to develop optimum bone strength through lifestyle measures, such as healthy diet, regular exercise, and not smoking.

Cardiovascular Disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD), of which coronary heart disease (CHD) is the most frequent, is the most common cause of death in women over the age of 60 years, and is relatively uncommon prior to menopause. About 50% of women develop CHD in their lifetime and 30% will die from the disease, with a further 20% developing a stroke. Functioning ovaries seem to provide some degree of protection, which is lost at menopause, particularly if this is premature. The postmenopausal decline in estrogen results in several metabolic changes, which can promote cardiovascular disease. Notable among these changes are an increase in blood total cholesterol levels of about 20% and triglycerides of 10–15%, an increase in insulin resistance, and a redistribution of fat from the hourglass figure of the younger woman with fat around the breasts and hips to more abdominal fat, all of which are risk factors for CHD (Stevenson, 2004). Nevertheless, the impact of menopause on CHD remains controversial among cardiologists and physicians, and particularly the potential role of HRT remains a matter of much debate. Recent, much-publicized studies from the United States, such as those from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) (Writing Group for the WHI Investigators, 2002) have demonstrated no benefit from HRT in women with established CHD and those who are several years postmenopause, but there is increasing evidence of a therapeutic window of opportunity whereby HRT, if started around the time of menopause, may delay the onset of CHD. This is supported by animal studies, but more research in women is required to clarify the situation and before there could be a recommendation of using HRT to prevent CHD.

Dementia

Dementia affects 10% of the population over the age of 65 years and 50% over the age of 85 years. Alzheimer’s disease, which is the most common cause of dementia, is more prevalent in women and there is some limited evidence of a preventive effect of HRT but, as with CVD, there is no benefit or even a worsening of the condition in those with established disease. Whether there is a potential benefit if started around the time of menopause also has yet to be established.

Skin And Hair

The skin is the largest organ of the body and like all tissues it changes with age, but in addition it is much affected by solar radiation and smoking. After menopause, there is a gradual reduction in thickness due to loss of collagen, the main constituent of the dermis, and loss of elasticity, and the skin becomes dry. Some 30% of the skin collagen is lost in the first 5 years after menopause, some of which can be replaced by estrogen replacement therapy, but there is no evidence that wrinkles are prevented.

Changes in hair growth with age are very variable but among postmenopausal women the most common complaints concern the decrease in body and pubic hair and the increase in facial hair. The latter may be partly due to a change in the ratio of androgens to estrogens.

HRT

HRT is intended to replace the deficiency of estrogen associated with the climacteric and is suitable for women experiencing menopausal symptoms that are affecting the quality of life and for some women at particular risk of developing osteoporosis. Estradiol, which is the main estrogen produced by the ovary before menopause, or conjugated equine estrogens (CEE), for example, Premarin®, are the most commonly prescribed worldwide. Estradiol may be given by tablet, transdermal patch or gel, vaginal ring or subcutaneous pellet implant, and CEE by tablet or vaginal cream. Women who have had a hysterectomy may take estrogen alone, otherwise a progestin, a synthetic form of progesterone (the other main hormone produced by the ovary during the normal menstrual cycle) is required in addition to protect the endometrium from overstimulation by estrogen, which could cause cancer. For women who are experiencing symptoms related to the urogenital tract only (see the section ‘Urogenital tract’), local, low-dose estrogen given by tablet, vaginal pessary, cream, or ring may be sufficient. These low-dose preparations act locally and do not have any beneficial effects on other menopausal symptoms or cause stimulation of other tissues such as the breasts or skeleton.

The WHI study (Writing Group for the WHI Investigators, 2002) reported that the use of HRT, with estrogen and progestin combined, for more than 5 years may be associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, venous thromboembolism (venous thrombosis and/or pulmonary embolism), and stroke of the order of about eight extra cases per 10 000 women per year. However, in women taking estrogen alone for up to 7 years, there was no evidence of an increased risk of breast cancer, though the other risks remained. Conversely, this study also confirmed a reduction in all osteoporotic fractures and a reduced risk of colorectal cancers.

The timing of the initiation of HRT seems to be critical, so that if started within 10 years of menopause there may be some protection of the coronary arteries from the development of atherosclerosis (Rossouw et al., 2007); as well, the risks of stroke and thromboembolism are also less than in older women. This finding has suggested that there is a window of opportunity for giving HRT in the early years after menopause, but starting therapy after the age of about 60 years, as in the WHI study in which the mean age of women on entering the trial was 63 years, is associated with a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular complications in particular.

In response to the WHI and other studies, drug regulatory authorities in many countries have issued guidelines for the use of HRT, which in summary advises the use of HRT only for the relief of significant menopausal symptoms, and to use the lowest dose for the shortest time, although neither of these criteria have been defined.

Alternative Treatments

Nonhormonal alternative treatments for menopausal symptoms and dietary supplements have received widespread use especially since the publicity in the media about the results of the WHI and other studies. There are limited, randomized controlled data suggesting some benefit in the relief of hot flushes with the use of plantderived preparations containing phytoestrogens. However, none can compare with the effectiveness of HRT and some herbal remedies such as black cohosh (cimicifuga racemosa) may cause significant side effects including liver damage.

Conclusion

Menopause is a natural and inevitable part of aging in women occurring at about two-thirds of the way through a normal life span. The loss of ovarian function provides some benefits and disadvantages to varying degrees. Greater awareness and knowledge of these changes will allow women to accept and cope with this transition. For those whose quality of life is significantly affected, the merits of HRT can be considered (Hickey et al., 2005).

Bibliography:

- Bachmann GA, Leiblum SR, Kemmann E, et al. (1984) Sexual expression and its determinance in the postmenopausal woman. Maturitas 16: 19–29.

- Barentsen R, van de Weijer PH, van Gend S, and Foekema H (2001) Climacteric symptoms in a representative Dutch population sample as measured with the Greene Climacteric Scale. Maturitas 38: 123–128.

- Bloch E (1952) Quantitative morphological investigations of the follicular system in women. Variations at different ages. Acta Anatomica 14: 108–123.

- Burger HG, Dudley EC, Hopper JL, et al. (1999) Prospectively measured levels of serum follicle-stimulating hormone, estradiol and the dimeric inhibins during the menopausal transition in a population-based cohort of women. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 84: 4025–4030.

- Burger H, Robertson D, Landgren B-M, and Dennerstein L (2004) Endocrinology of the menopause and menopause transition. In: Critchley H, Gebbie A, and Beral V (eds.) Menopause and Hormone Replacement, pp. 3–14. London: RCOG Press.

- Faddy MJ, Gosden RG, Gougeon A, et al. (1992) Accelerated disappearance of ovarian follicles in mid-life: Implications for forecasting menopause. Human Reproduction 10: 1342–1346.

- Freedman RR (2001) Physiology of hot flashes. American Journal of Human Biology 13: 453–464.

- Hickey M, Davis SR, and Sturdee DW (2005) Treatment of menopausal symptoms: What shall we do now? The Lancet 366: 409–421.

- Hunter MS (1996) Mental changes: Are they due to estrogen deficiency? In: Birkha¨ user MH and Rozenbaum H (eds.) Menopause European Consensus Development Conference, pp. 73–77. Paris, France: Editions Eska.

- Lindsay R, Ettinger B, McGowan JA, Redford M, and Barrett-Connor E (2002) Osteoporosis and oral bone loss in aging women: Risks and therapy. In: Wenger N, et al. (eds.) Women’s Health and Menopause: A Comprehensive Approach, pp. 181–202. Bethesda, MD: NIH Publication No. 02–3284.

- Molnar GW (1975) Body temperatures during menopausal hot flashes. Journal of Applied Physiology 38: 499–503.

- Rossouw J, Prentice RL, Manson JE, et al. (2007) Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease by age and years since menopause. Journal of the American Medical Association 297: 1465–1477.

- Sambrook P and Cooper C (2006) Osteoporosis. The Lancet 367: 2010–2018.

- Stevenson JC (2004) Metabolic effects of the menopause and hormone replacement therapy. In: Critchley H, Gebbie A, and Beral V (eds.) Menopause and Hormone Replacement, pp. 15–22. London: RCOG Press

- Sturdee DW, Wilson KA, Pipili E, and Crocker AD (1978) Physiological aspects of menopausal hot flush. British Medical Journal 2: 79–80.

- Writing Group for the Women’s Health, Initiative (WHI) Investigators (2002) Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women. Journal of the American Medical Association 288: 321–333.

- Birkha¨ user MH, Barlow DH, Notelovitz M, and Rees M for the International Menopause Society (2005) Health Plan for the Adult Woman; Management Handbook. Oxford, UK: Taylor and Francis.

- Critchley H, Gebbie A, and Beral V (2004) Menopause and Hormone Replacement. London: RCOG Press.

- Genazzani AR (2006) Postmenopausal Osteoporosis; Hormones and Other Therapies. Oxford, UK: Taylor and Francis.

- Gordon T, Kannel WB, Hjortland MC, et al. (1978) Menopause and coronary heart disease: The Framingham Study. Annals of Internal Medicine 89: 157–161.

- Lauritzen C and Studd JWW (2005) Current Management of the Menopause. Oxford, UK: Taylor and Francis.

- Nedrow A, Miller J, Walker M, Nygren P, Huffman LH, and Nelson HD (2006) Complementary and alternative therapies for the management of menopause related symptoms: A systematic evidence review. Archives of Internal Medicine 166: 1453–1465.

- Pines A, Sturdee DW, Birkha¨ user MH, Schneider HPG, Gambacciani M, and Panay N on behalf of the Board of the International Menopause Society (2007) IMS Updated Recommendations on postmenopausal hormone therapy. Climacteric 10: 181–194.

- Rees M and Purdie DW (2006) Management of the Menopause. London: Royal Society of Medicine Press and British Menopause Society Publications.

- Sturdee DW (2004) The Facts of Hormone Therapy for Menopausal Women. London: Parthenon.

- Tomlinson J (2005) Sexual Health and the Menopause. London: Royal Society of Medicine Press and British Menopause Society Publications.

- Wenger N, Paoletti R, Lenfant CJM, and Pinn VW (2002) International position paper on women’s health, menopause: A comprehensive approach.

- Bethesda, NJ: NIH Publication No. 02-3284, July (2002) National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, Office of Research on Women’s Health, National Institutes of Health and Giovanni Lorenzini Medical Science Foundation.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.