This sample Organization and Financing of Long Term Care Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Introduction

Long-term care comprises a set of nonmedical as well as medical services delivered to individuals who have lost some capacity for self-care because of chronic illness or disability. It differs from other types of health care in that its primary goal is not to cure ill health but to allow individuals to achieve and maintain optimal levels of personal functioning. Promotion of quality of life is a core aim. Long-term care can therefore include provision of medical care, but tends to be more closely associated with an array of social, personal, and supportive services that provide help with domestic tasks (such as shopping, cleaning, preparing meals), personal care tasks (dressing, bathing), and personal concerns (safety). Specialized housing might be provided.

Most of the long-term care received by people who live at home is provided by family members or other informal (unpaid) carers. But, as we shall describe later, in most high-income countries, there has been a gradual shifting of the balance of care – away from the family and toward formal care services delivered by paid staff employed by health-care agencies, municipalities, voluntary (nonprofit, nongovernmental) organizations or private sector bodies.

Other key parameters of a long-term care system vary quite noticeably from country to country, again as we discuss later. The mechanisms used to finance long-term care can include collectively organized risk-pooling arrangements such as social insurance or tax-based funding, but across much of the world there is still heavy reliance on privately financed care, whether through out-of-pocket payments (user charges) or voluntary insurance policies. Another variable is the locus of care, with countries choosing to rely to differing degrees on residential forms of provision such as nursing homes, staffed care facilities and long-stay hospital wards. It is generally held to be preferable to provide long-term care in ordinary community settings, such as an individual’s own home, although this is not always easy to achieve. Another relevant parameter is the balance between provider sectors, with some long-term care systems heavily reliant on public services and others dominated by services delivered by private and voluntary sector bodies.

Long-term care services are used by people with chronic health and related conditions. Older people are particularly heavy users of such services, and this pattern will undoubtedly persist given the aging of the world’s population. We focus primarily on this age group.

Demographic Change

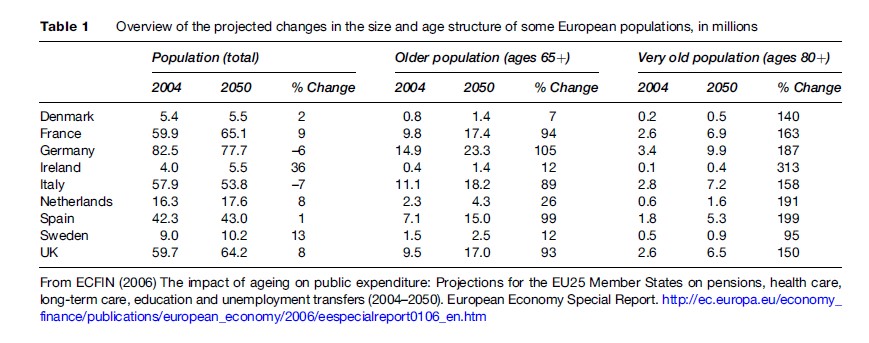

Population aging is a worldwide phenomenon. The challenge that this generates can be illustrated for some European countries (Table 1). Countries such as Germany and Italy, for example, are expected to see decreases in total population between 2004 and 2050, whereas the Irish population is expected to grow by more than a third, and the population of Sweden by 13%. Generally, high-income countries will see decreases in the population aged 15–64, conventionally the most productive ages in terms of contributions to national economies. Projected changes in the older population (age 65 and above) will be pronounced. For example, in the UK there were 9.5 million older people in 2004, projected to almost double to 17 million by 2050. Of more interest for long-term care systems is the expected growth in the old age group. For example, again looking at the UK, there is a projected increase of 150% in the number of people aged 80 or above, but this pales by comparison to Ireland, Spain, the Netherlands, and Germany.

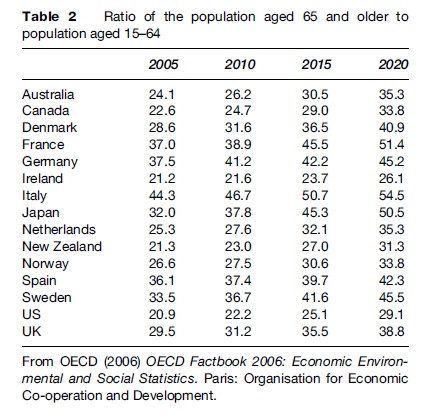

Central to many concerns about future long-term care arrangements is the demographic balance between dependent older people and the labor force. The ratio of the population aged 65 or older to those aged 15–64 is already quite high in Italy, Germany, France, and Spain, and by 2020 will be much higher (Table 2).

Why are these demographic patterns important? Use of long-term care and medical services is high among older people, and an aging population will inevitably put growing pressure on care services. This can be illustrated by projections of needs and expenditure for England using the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) model (Wittenberg et al., 2006). The model has projected that the number of occupied residential places (in residential care homes, nursing homes, hospitals) would need to expand by 115% between 2002 and 2041 just to keep pace with demographic change, while care support for older people in their own homes would need to increase by 103%. But these needs could be much higher if the proportion of older people who are dependent increases (perhaps because people with high care needs survive into old age as a result of improvements in medical technology), or if quality of care improvements are demanded by future cohorts of service users, or family members are less able or willing to provide unpaid care for dependent older relatives (perhaps because of changing labor force participation patterns and geographical mobility).

The PSSRU model estimates that long-term care expenditure would need to increase by 325% in real terms between 2002 and 2041 to meet demographic pressures and allow for expected real rises in unit costs. Projections of this kind are subject to uncertainty, of course, but they vividly illustrate why there is so much discussion of population aging and its implications.

Mixed Economy Of Care

One of the complications in planning long-term care is that many older people have multiple needs. If a care system is well developed and adequately resourced it is likely that these needs will be identified, assessed, and addressed by a variety of agencies. Thus, for example, there might be roles for health services, social care, housing providers, social security agencies, and others in supporting older people. The financing arrangements could be very different between these agencies, with implications for who pays for what, and there could be the substantial challenge of coordinating care across organizational boundaries.

An added issue is that the care needed by older people and their families could be delivered by government (public sector), private (for-profit) or voluntary (nonprofit, charitable) organizations. Of course, most support and care is not provided through structured organizations at all, but by unpaid relatives and other individuals providing informal care. Most countries have a thriving mixed economy of provision – a mix of services delivered by a mix of agencies and individuals, each with potentially different motivations and funding bases. In understanding how long-term care systems operate, we therefore need to pay attention to the roles played by families, the types of formal service provided, and the ways that those services are financed. The next three sections address these topics in turn. We then consider a relatively new development in some long-term care systems – self-directed services.

Informal Care

Reliance On Unpaid Caregivers

Changing demographic patterns, family composition, labor force participation and geographical mobility are reducing the (potential) pool of family caregivers for older people. The substantial inputs of unpaid family caregivers (in terms of practical help, companionship, assistance in getting out, and general supervision) often go unrecognized. Yet without them either the state or civil society (voluntary/charitable) bodies would have to step in to provide formal care support, or older people or their families would have to purchase care themselves. The alternative would be poor and deteriorating quality of life for older people and others with long-term care needs.

The effects on caregivers can be considerable. On the positive side, most caregivers gain great satisfaction from their contribution to maintaining and improving the quality of life of the person they support, often a loved relative. However, more attention focuses on the negative aspects, and particularly the effects on health, stress, employment, and income. Caregiver health problems are particularly associated with supporting older people with high-level needs (Moise et al., 2004). One of the most tangible effects of caring is reduced opportunity to work and reduced income: Evandrou (1995) found that men and women who provide 20 or more hours per week of informal care have earnings from employment that are 25% lower than the earnings of employed noncaregivers.

Family caregivers, and particularly women, are absolutely the mainstay of all long-term care systems. Not surprisingly, most governments have therefore introduced a range of measures that seek to encourage families to continue to provide care for dependent relatives. Adequate and appropriate health and social services provided to older people, both in institutions and at home, are known to be a major factor in supporting the inputs of family carers and reducing the burden of care on their shoulders. Respite care is central to most countries’ support programmes for caregivers: It offers families a break from their caring responsibilities, and could be offered in the home, or in a care facility (during the day or overnight for a few days). Financial support is available in some countries, through tax credits (as in Canada, Spain, the US), pension credits (as in Canada, Germany, the UK), or social care budgets (as in Australia, France, Sweden) or through self-directed payments (see the section titled ‘Financing’ below). Initiatives have also been taken to provide families with better general information, advocacy, education, and training about needs, how to meet them, and the availability of local support. Employment-friendly policies are also being introduced in some countries to help people combine a career with caring responsibilities.

Experience in Canada illustrates many of the practical and policy issues in relation to informal care. Unpaid caregivers provide more than 80% of the support needed by people with long-term conditions in Canada (Statistics Canada, 2002). Although men are providing more care than in the past, women still constitute the majority of caregivers. Data from Statistics Canada’s 2002 General Social Survey reveal that 59% of people providing care to an older person in the preceding 12 months were women. According to Smale and Dupuis (2002), 92% of caregivers of older people in Canada are family members, 53% spouses, and 38% adult children of the person being supported. One in 25 caregivers said they had become economically inactive because of their caring responsibilities.

A mix of programs and policies is in place at federal, provincial, and territorial levels to support caregivers. One of the main ways of providing support is through provision of home care services, whether direct to care receivers or specifically to meet the needs of caregivers through, for example, respite services. These programs are largely the responsibility of provincial departments of health or social services, with the exception of veterans and members of First Nations, who fall under federal jurisdiction. While there have been calls for the development of a universal home care program, current federal health policy does not provide standards or guidelines for the development or delivery of home care services. As a result, home care programs vary widely across the country and meet the needs of caregivers with varying degrees of success.

One emphasis in Canada has been to use the tax system to provide financial support to those providing care to disabled or elderly relatives. There are a number of tax relief measures that can be claimed at the federal level, although a criticism that has been made is that these measures are least useful to those who most need them: Although women constitute the majority of caregivers, data from the 2000 tax year indicate that only 39% of Caregiver Credit claimants were women, which may be partly because many women caregivers do not have sufficient income to benefit from a nonrefundable credit (Shillington, 2004). While many caregivers meet some of the eligibility criteria for most tax deductions and credits, they rarely meet all, and so do not benefit from financial compensation policies. The complexity is also said to put off some potential beneficiaries.

The other national program offering financial compensation to caregivers is the Compassionate Care Benefit, an element of the Employment Insurance program. It came into effect in 2004 and provides temporary income support for eligible workers who need to take leave from work to provide care to a family member who is likely to die within the next 6 months. There are many significant restrictions on eligibility for receipt of this benefit: It is available, for example, only to close relatives who are eligible for employment insurance (so that, for example, self-employed persons are ineligible).

The provinces and territories have also used the tax system to provide financial assistance to caregivers. But tax credits available at this level, where they exist, largely parallel those found at the federal level, although amounts and eligibility criteria vary. There are also some sales tax exemptions for respite care.

Provision

Many of the needs of older people stem from deterioration in their health and are most usually appropriately met by health-care services. Other needs are more appropriately met by social care providers. But the boundaries between these sets of needs are hard to draw, and different patterns of service provision have grown up in different countries, influenced by national culture, financing arrangements, availability of skilled professionals and the caprices of day-to-day decision making. The distinction between health and social care has potentially important implications both for the level of cost (for example, needs may be excessively medicalized or specialist treatment underprovided) and for the balance of funding (if different eligibility criteria influence threshold levels of dependence, for instance). In turn, these could create (perverse) incentives: Cost-shifting is a problem in some countries, as is the risk of people falling between two separate care systems. Sweden is one country that appears to have solved long-standing problems such as hospital bed blocking and nursing home funding responsibilities, but new boundary issues have arisen there, concerning rehabilitation, home nursing, assistive technology and so on.

Although there are many differences between countries, there is a common core of (non-family) services that can be said to comprise long-term care, including needs assessment, counselling and advice, self-help support groups, respite care, crisis management, support centers, day programs, support for people in their own homes (so-called home care, including home help, meals, and community nursing), residential and nursing home provision, and – increasingly – a range of housing-with-support services (such as sheltered housing, extra-care housing and some retirement communities).

Institutional Care

The long-stay hospital ward for older people is gradually being phased out in many Western countries, although it remains an unwelcome feature of care systems in parts of Eastern Europe. More policy attention in Western countries has therefore turned to the balance between institutional care (which now usually means residential and nursing home care) and home care.

An OECD (1996) study found suggestions of some convergence around a level of roughly 5% of older people supported in institutional settings, ranging from below 1% in Greece and Turkey (in the early 1990s or late 1980s) to above 6.5% in Canada, Finland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and Norway. Countries with an above-average level of bed provision were generally trying to reduce it and those below the average were generally trying to expand provision. Discussions on the appropriate balance of care have included arguments about relative effectiveness (for whom is residential/ nursing home care more effective – in terms of promoting quality of life and other outcomes – and when?), relative cost (both in total and to various agencies, especially health and social care), and user and family preferences (themselves influenced by factors such as perceptions of quality, availability of informal care, the broader family centered culture in certain societies, and personal cost).

One consequence of this shifting balance between institutional and other forms of care is that older people tend to get admitted to care homes when already quite dependent, for example at later stages of dementia. This can leave families carrying a heavy burden, and caregiver-related factors are common reasons for admission. Another consequence is that a high proportion of residents in care homes and other highly staffed congregate care settings today have dementia. Decisions on what is an appropriate balance of provision need to be thought through. For example, the availability of places in care homes has significant impacts on rates of delayed discharge from hospital in England (Ferna´ndez and Forder, 2007).

Home Care

The OECD (1996) found a great deal of intercountry variation in the provision of home care. For example, no more than 5% of all older people in Austria, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Spain were receiving home care at the time of the study, compared to more than 10% in Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden. There was no evidence of movement toward a similar proportion. However, comparisons of home-based care are difficult to make across countries: ‘‘How much of this [observed] variation is due to differences in definitions of home care or other methodological issues, rather than due to the actual use of such services, is not clear’’ (Gibson et al., 2003: 3).

Notwithstanding this difficulty, the extent and nature of development of what are sometimes called intermediate care arrangements (housing with various levels of care support) also vary considerably. A common phenomenon has been the transformation of most home care services from the traditional home help, focused on household chores, to services that concentrate on personal care. This transformation has often gone hand in hand with the development of intensively supported home care, often costing as much as a place in a care home. It is becoming increasingly common to find long-term care systems targeting available resources on people with the greatest needs (hence the development of intensive home care, for example), at the expense of low-level care for people with fewer needs. Indeed, collectively financed low-level support has virtually disappeared in some countries (such as England).

Provider Pluralism

Provider pluralism is another pervasive and increasingly visible feature of many long-term care systems. The public sector has often been the largest provider of formal services, but not-for-profit (voluntary) and for-profit (private) organizations have also been high-volume and/or high-profile contributors in the mixed economy of care (Kendall et al., 2006). Responsibility for strategically coordinating or commissioning care still rests predominantly with public sector bodies, but increasingly it is nonpublic bodies that actually deliver services in the field.

Policy debates in some countries have kept services and financing distinct when discussing the future of long-term care (such as in the UK), although the two are obviously closely connected in practice. The sectoral balance of provision affects the balance of funding responsibilities: For example, charitable donations can be used to subsidize state or individual funding of services. The sectoral balance of provision may also affect the overall cost of care if one sector is demonstrably and consistently less expensive and/or more cost-effective than another.

Coordination

Good interagency coordination of long-term care is imperative if individual and family needs are to be met, which requires collaborative approaches to financing. Without effective coordination, yawning gaps could open up in the spectrum of support: Even in well-resourced care systems there are large numbers of people whose long-term care needs go unrecognized or unmet. Wasteful duplication of effort is another possibility. Countries, states, and municipalities differ in their service and agency definitions, responsibilities, and arrangements, and therefore in their interagency boundaries and the kinds of connected action that spans them. One of the major organizational resource challenges, therefore, is to coordinate service funding in ways that are effective, cost-effective, and fair. Cost shifting and problem dumping between agencies will not help individuals or families, but recognition of economic symbiosis could help decision makers fashion improved responses to needs through pooled budgets, jointly commissioned programs and other whole system initiatives.

In some countries, such as the Netherlands and Scandinavia, there have been efforts to integrate housing and health/social care to improve service coordination and promote independence and self-care.

Quality Of Care

Concern has been widely expressed about quality of care, how to improve it and how to assure it through appropriate regulatory mechanisms. There are inherent difficulties in measuring some aspects of quality, and service users with a moderate or high degree of cognitive impairment, for example, are unlikely to be able to participate as informed consumers using their voice to bring about change.

One factor working against quality improvements is the low status and high rate of turnover of staff. A number of countries are experiencing shortages of qualified or skilled staff for long-term care services, and particularly to work in services for people with dementia. One of the reasons is undoubtedly that rates of pay seem to be universally low, hindering recruitment and fostering turnover.

Financing

The main approaches to funding long-term care are out-of-pocket payments; voluntary insurance (sometimes called private insurance); tax-based support from general tax revenue; and social insurance. The last of these includes social health insurance but could be broader to include social care. All but the first are prepayment arrangements. They differ one from another in the personal–collective funding balance, extent of risk pooling, and nature of government intervention. Policy instruments applied to potentially any of these funding approaches include providing information and advice, regulation, subsidies, tax raising, transfer payments, and direct provision of services. All financing arrangements involve some redistribution over the life cycle, whether explicitly through contributions to long-term care or other insurance policies during the working years, or through tax or social insurance contributions (linked closely to employment) or through investment in housing equity.

Almost all high-income countries rely heavily on pre- payment systems of revenue collection, widely held to be preferable to out-of-pocket payments when an individual’s risk of needing long-term care is very uncertain, and, when the need arises, if the attendant costs (of care) and/or losses (of earnings) could be catastrophic. Prepayment contributions pool risks, and therefore redistribute benefits toward people with greater needs. They also have the potential to redistribute in favor of poorer individuals, either because need is inversely correlated with income, or purposively by making arrangements progressive so that poorer individuals pay proportionately less than wealthier individuals for equivalent care. Out-of-pocket payment systems (from private savings, equity release and so on) generally do not have these same advantages.

Out-Of-Pocket Payments

Although prepayment systems dominate, in many countries there are out-of-pocket charges for some services, whether as co-payments (a specific amount is paid for a service), co-insurance (an agreed percentage of cost is charged) or deductibles (an agreed amount is paid before insurance kicks in). There are various rationales for introducing out-of-pocket payments, including to raise revenue (if wealthier individuals can afford to pay, why not charge them?), to discourage unnecessary service use (moral hazard), and to create price sensitivity that might help direct service users to more cost-effective and appropriate treatments. But out-of-pocket payment mechanisms usually have undesirable impacts on access and equity, discouraging the use of essential as well as nonessential services, and delaying demand and utilization that might later mean substantially increased costs.

Voluntary Insurance

Voluntary insurance is taken up and paid for at the discretion of individuals (hence the label voluntary) or perhaps by employers on behalf of individuals. Insurance policies might be offered by public, quasi-public, for-profit or nonprofit organizations. Generally speaking, voluntary insurance is less important in European health-care systems than in the U.S., where it accounts for half of health-care expenditure (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2003). However, long-term care insurance has failed to establish itself even in the U.S., and has certainly not proved popular in countries where tax based or social insurance arrangements are in place ( Johnson and Uccello, 2005).

People individually purchasing insurance have lower bargaining power than when insurance arrangements are made by employers or the state, which in turn could affect the benefits covered. Inherent in voluntary prepayment systems are disadvantages such as adverse selection and cream skimming, where higher risk groups (such as those with chronic conditions) may find insurance unaffordable and lower risk groups may feel that their own premiums are too high. Insurance plans may also exempt existing conditions from the benefit packages, which could be a difficulty for long-term care. If there is no charge at the point at which a service is used there may be excessive utilization, the so-called moral hazard problem that might be addressed by introducing co-payments at point of use.

Tax-Based Financing

Many health and social care systems are funded from national, regional, or local taxes. If the tax that generates the revenue is progressive (as with income tax) and eligibility for benefits is not income-related, then long-term care financing will also be progressive. But long-term care financing could be regressive if financed from indirect taxes (such as sales or value-added tax), because poorer individuals often contribute larger proportions of their incomes. Generally, however, at least in discussions of health-care financing in high-income countries, tax-based systems are seen as the most progressive and equitable of all arrangements (Mossialos et al., 2002), and the same would apply to long-term care.

Payments are mandatory, and scale economies can be achieved in administration, risk management, and purchasing power. Services (or cash payments in some countries – see the section on self-directed services below) are provided on the basis of need, and there is obviously also the potential to allocate or distribute services (or their cash equivalents under self-directed care arrangements) on the basis of income or assets. For those who advocate health or long-term care as a right, tax-based systems fit the bill, while those with conservative leanings might view such arrangements as erosions of personal responsibilities and freedom.

Tax-based systems have limitations. Funding levels may fluctuate with the state of the national economy: When an economy is not doing well, there is a tendency to cut back on publicly funded programs. Competing political and economic objectives make a tax-based system less transparent, and bureaucracy can add to inefficiency, perhaps reflected in long waiting lists (although there is also symptomatic underfunding). Service users may view tax-based systems as offering them limited choice, but uninsured individuals in an alternative financing system might argue that they face no choice whatsoever.

Social Insurance

Care systems based on social insurance generate their revenues from salary-based contributions administered and managed by quasi-public bodies. Employers also make contributions, and transfers are usually made from general taxation to sickness funds to provide cover for unemployed, retired, and other disadvantaged or vulnerable people. One of the most interesting financing arrangements is the system introduced in Japan in 2000, which have attracted worldwide attention. Mandatory long-term care social insurance was introduced in 2000, operated by the more than 3000 municipalities under central government legislation. (The decision was made to go with a social insurance rather than tax-based model on a number of grounds; see Ikegami, 2004.) The insurance is financed 50% from taxes (half from national taxes, a quarter each from local and regional taxes) and 50% from insurance premiums paid by people aged 40 and above. For people in employment, the premium is equivalent to 0.6% of income up to a ceiling, with employers and employees sharing this cost. For older people, premiums are deducted from pensions and are also income-related (Campbell and Ikegami, 2003). Co-payments amounting to 10% of care costs are paid.

Eligibility is based solely on need for everyone aged 65 and over and those aged 40–64 with aging-related disabilities. Insured people in need of care are assessed on application and classified into one of six care levels according to need. A fee schedule is set nationally according to the level of need. The role of a care manager was newly created with the introduction of the insurance system to draw up care plans reflecting individual needs. The scheme covers residential and home care services. Cash benefits are not paid – unlike in Germany, for example – partly to move care away from the traditional heavy reliance on female carers (particularly in a context of a declining ability and willingness of families to provide support; Ikegami, 2004), partly to help long-term care provision to expand (Campbell and Ikegami, 2003).

Tax revenues may also be called upon to cover deficits in social insurance funds, especially if the working population is too small to generate sufficient revenue to cover the population eligible to receive benefits. Enrollment is usually mandatory, and although premiums are not risk-adjusted, they tend to be linked to income so that pooling allows for redistribution according to both need and income. A disadvantage is that the link between financing and employment may constrain job mobility and hence economic competitiveness (at the national level).

Both tax-based and social insurance-dominated systems take account of ability to pay and cover vulnerable and low-income groups.

Comparing The Options

A number of criteria have been alluded to in describing the relative advantages of the different financing methods. Efficiency is obviously central – ensuring that the highest volume or best quality of care is achieved from a given funding base. Financing arrangements are obviously not desirable if they do not allow full assessment of individual needs, or embody inappropriate incentives to use residential care (or not to use it enough), or shift costs between agencies so that support arrangements are poorly coordinated or have heavy management or transaction costs.

Equity is also especially relevant as a criterion, looking at both the services and benefits received as well as funding contributions, and has been widely discussed in connection with long-term care financing options. Other criteria discussed include affordability, sustainability, independence, self-respect, dignity, choice, and social solidarity.

Governments of different political hues will give different emphasis to these and other criteria. What is common across many countries today is exploration of financing options that shift some of the burden away from the state, whether in tax-financed systems or because of the need to subsidize or underpin other financing arrangements.

Health And Long-Term Care Differences

Different financing arrangements can be employed for health and long-term care systems, or indeed for different services within these systems. In particular, there can be different regimes for charging users. In England, there is currently considerable tension between health care (which is free at the point of use) and social care (which is means-tested). People with dementia or other long-term conditions moving from a hospital ward to a nursing home might suddenly find themselves liable to pay (often substantial) charges for their care, even though their primary need is generated by a health problem.

Expenditure Levels

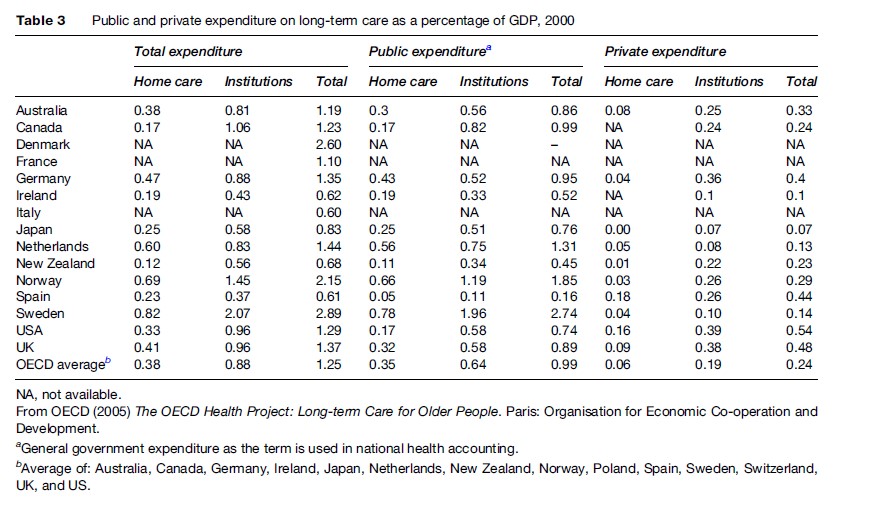

The OECD (2005) estimated public and private expenditure on long-term care as a percentage of GDP in 2000 (Table 3). (Public expenditure in this table is equivalent to general government expenditure as the term is used in national health accounting.) Total expenditure ranged from lows of 0.6% of GDP in Italy and Spain to greater than 2% in Scandinavian countries. The average of 14 countries covered by this OECD report was 1.25%. Generally, public sector spending on long-term care dominated private expenditure, except in Spain. However, these OECD data only include expenditure related to medical services and so underestimate total long-term care spending.

Self-Directed Services

A noticeable trend across some countries is the development of self-directed (or consumer-directed) services (Ungerson and Yeandle, 2007). The primary aim is to give more independence and choice to older people and thereby give them greater control over their lives. An increasingly common way to do so is to hand funding over to individuals to purchase their own care support. Voucher-like arrangements are also being used. The German long-term care financing system offers the devolved funds option, while in England there are opportunities for people assessed as eligible for state-supported long-term care to receive funding through direct payments or individual budgets (Knapp, 2007).

There are a number of reasons for these initiatives. Social work theory – which certainly exerts influence over long-term care systems in some countries – has long emphasized independence and empowerment, which gives normative professional credibility to devolved purchasing or commissioning powers. There is also a belief that such arrangements can improve quality of care while being cost-effective. The approach appeals both to the political right because of its links to market mechanisms, and also to the center left because of its connections with choice and accountability in public services. From the user perspective, self-directed services can be attractive because of the empowerment offered and are clearly supportive of rights-based agenda. They might also help to break down barriers between sectors and budgets, because the funding can be used within the gray areas between health, social care, housing and so on.

However, there are potential drawbacks. Self-directed arrangements place considerable responsibility for finding, monitoring, and purchasing services on the shoulders of long-term care users, many of whom could be frail or cognitively impaired. Family carers might not be available to help. The funding transferred to individuals might be too little to allow them to access services they want or feel they need. Individual purchasers will have little bargaining power relative to service providers (compared to, say, large purchasers such as a municipality or social insurance fund), and there is the risk of exploitation by providers or financial advisers. Although brokerage (advisory, support) services are usually established in self-directed care systems, coverage or quality might not be adequate.

Conclusions

Across the world, populations are aging, and increasingly governments are worrying about the future affordability of long-term care, given the close correlation between age and the need for support in self-care and personal tasks. One area of concern is the availability of unpaid support by families and others, which remains the most common source of long-term care. The future supply of informal care is likely to be considerably lower than at present because of changing demography, growing labor force participation by women, and changing societal expectations. There is also growing recognition of the high psychological and opportunity costs of being a caregiver, and governments are gradually introducing information and advice, financial support, respite care, and employment-friendly policies.

Particular attention is also being paid to the organization of formal services provided by municipalities, voluntary organizations (civil society), and for-profit private companies. Historically there was quite heavy reliance in some countries on long-stay hospital services, nursing homes, and residential care facilities, but a common policy emphasis today is to try to substitute community based services, on the grounds of quality of life, cost, and the personal preferences of older people. Home care services are themselves often being transformed from traditional home help models to personal care, and in some countries are being targeted on people with the greatest needs in efforts to avoid or delay admission into institutional facilities. There is also an observable tendency across a number of countries to develop long-term care arrangements that blur the boundaries between institutional and community-based provision, and between health and social care, while also developing specialist resources for conditions such as dementia.

As countries increase the resources devoted to long-term care, they wrestle with the challenge of how to finance services over the coming decades. One consequence has been to try to shift more of the funding balance away from collective responsibility and toward individual service users and their families. Nevertheless, there remains heavy reliance on prepayment financing arrangements (through taxation or insurance) that generally redistribute in favor of people with greater needs and lower incomes. While many governments are exploring ways to reduce their own financial responsibilities, at the same time there is growing government activity in regulating long-term care systems, providing safety net support, seeking to monitor care markets, and improving quality assurance mechanisms. Self-directed systems are being introduced in some countries, giving control over the selection and purchasing of services to the people who actually have long-term care needs, and this kind of arrangement seems likely to grow considerably in the future.

Bibliography:

- Campbell JC and Ikegami N (2003) Japan’s radical reform of long-term care. Social Policy and Administration 37: 21–34.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2003) Health insurance coverage – National Center for Health Statistics. http://www.cdc. gov/nchs/fastats/hinsure.htm (accessed September 2007).

- ECFIN (2006) The impact of ageing on public expenditure: Projections for the EU25 Member States on pensions, health care, long-term care, education and unemployment transfers (2004–2050). European Economy Special Report. http://ec.europa.eu/ economy_finance/publications/european_economy/2006/ eespecialreport0106_en.htm (accessed September 2007).

- Evandrou M (1995) Employment and care, paid and unpaid work: The socioeconomic position of informal carers in Britain. In: Phillips J (ed.) Working Carers. Aldershot, UK: Avebury.

- Ferna´ ndez J-L and Forder J (2007) Consequences of local variations in social care on the performance of the acute health care sector. Applied Economics. In press.

- Gibson MJ, Gregory SR, and Pandya SM (2003) Long-Term Care in Developed Nations: A Brief Overview. Washington DC: AARP.

- Ikegami N (2004) Opening Pandora’s box: Making long-term care an entitlement in Japan. In: Knapp M, Ferna´ ndez J-L, Netten A, and Challis D (eds.) Long-Term Care: Matching Resources and Needs. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate.

- Johnson RW and Uccello CE (2005) Is Private Long-term Care Insurance the Answer? Issue in Brief No. 29. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

- Kendall J, Knapp M, and Forder (2006) Social care and the nonprofit sector in the western developed world. In: Powell WW and Steinberg R (eds.) The Nonprofit Sector: A Research Handbook, Second edition, pp. 415–431. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Knapp M (2007) Social care: choice, money, control. In: Hills J, Le Grand J, and Piachaud D (eds.) Making Social Policy Work: Essays in Honour of Howard Glennerster. Policy Press.

- Mossialos E, Dixon A, Figueras J, and Kutzin J (eds.) (2002) Funding Health Care: Options for Europe. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

- Moise P, Schwarzinger M, and Um MY (2004) Dementia care in 9 OECD countries: A comparative analysis. OECD Health Working Papers No. 13, OECD, Paris, France.

- OECD (1996) Caring for Frail Elderly People: Policies in Evolution. Paris, France: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

- OECD (2005) The OECD Health Project: Long-term Care for Older People. Paris, France: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

- OECD (2006) OECD Factbook 2006: Economic Environmental and Social Statistics. Paris, France: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

- Shillington R (2004) Policy Options to Support Dependent Care: The Tax/Transfer System. Prepared for Healthy Balance.

- Smale B and Dupuis S (2002) Highlights report: preliminary results from the study on needs of caregivers of persons with Alzheimer Disease or a related dementia and community support services in Ontario. Murray Alzheimer Research and Education Program. Ontario, Canada: University of Waterloo. http://marep.waterloo.ca/projects. html.

- Statistics Canada (2002) General Social Survey (GSS). Ottawa, Canada: Statistics Canada.

- Ungerson C and Yeandle S (eds.) (2007) Cash for Care in Developed Welfare States. Cambridge: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wittenberg R, Comas-Herrera A, King D, Malley J, Pickard L, and Darton R (2006) Future demand for long-term care, 2002 to 2041: Projections of demand for long-term care for older people in England. PSSRU Discussion Paper 2330. London: London School of Economics. http://www.pssru.ac.uk/pdf/dp2330.pdf.

- Comas-Herrera A, Wittenberg R, Pickard L, Knapp M, and MRC-CFAS (2007) Cognitive impairment in older people: Its implications for future demand for services and costs. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. Jul 2 [E-pub ahead of print].

- Karlsson M (2002) Comparative analysis of long-term care systems in four countries, interim report. International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis: Laxenburg, Austria.

- Merlis M (2000) Caring for the frail elderly: An international review. Health Affairs 19: 141–149.

- Pickard L, Wittenberg R, Comas-Herrera A, Davies B, and Darton R (2000) Relying on informal care in the new century? Informal care for elderly people in England to 2031. Ageing and Society 20: 745–772.

- Pickard L (2004) Caring for Older People and Employment. London: Audit Commission.

- Wanless D, Forder J, and Ferna´ ndez J-L (2006) Securing Good Care for Older People: Taking a Long-Term View. London: King’s Fund.

- Wiener J (2004) Home and community-based services in the United States. In: Knapp M, Ferna´ ndez J-L, Netten A, and Challis D (eds.) Long-Term Care: Matching Resources and Needs. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate.

- Wittenberg R, Sandhu B, and Knapp M (2002) Funding long-term care: The private and public options. In: Mossialos E, Dixon A, Figueras J, and Kutzin J (eds.) Funding Health Care: Options for Europe. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.