This sample International Issues in Worker Health and Safety is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Despite the fact that more than half of the International Labor Office’s Conventions relate directly or indirectly to occupational health, workers around the world, particularly in developing countries, continue to suffer a significant burden of disease from illness and injury. For example, Rantanen et al. (2004) estimate that approximately 250 million injuries, 150 million diseases, and over 1.1 million fatalities arise as a result of workplace hazards annually, with rates between 10 and 20 times higher in newly industrialized and developing countries.

What are the factors driving this anomalous situation in which, despite scientific advances in the tools available to control workplace hazards, billions of working people remain deprived of their right to a safe working environment, access to health care, and benefit from scientific development?

Three broad sets of factors help explain why worker health and safety continues to pose a major global challenge. First, the global trade and economic context shapes a wide set of forces determining both the hazards to which workers are exposed and the institutional and human resources available to deal with these hazards. Second, particular vulnerabilities have been generated by global trade and economic developments for different sets of working populations and groups. Third, the limitations of current occupational health service (OHS) strategies to address these problems adequately in many developing country contexts require new strategies for advancing global capacity to address these needs. These factors are explored in the context of the global HIV pandemic and the implications for workers’ health and safety.

Globalization, Economic Policies, And Trade: Implication For Occupational Health

Workers at the Auto Trim and Custom Trim plants put leather covers on steering wheels sent to U.S. automakers. Chemical adhesives are used to glue leather covering onto the metal steering wheels, and then solvents are used to remove excess adhesives. The work involves repeated, forceful motions in awkward positions for the entire eight-hour shift. .. .Production quotas for the cells were also raised, increasing chemical exposures and ergonomic hazards. – Coalition for Justice in the Maquiladoras writing about the Auto Trim plant, Matamoros, Mexico, cited in Brown (2005)

Yes, I have money, but I have lost my health. I have a job – but I have no rights and no security. – Colombian flower worker, cited in London and Kisting (2002)

In light of the experience of workers employed in the myriad expanding production settings created by the increasing integration of trade across the world, how does one interpret claims that globalization has exerted an indirect positive effect on nutrition, infant mortality, and other health issues, such as workers’ health and safety? There is mounting evidence that the impact on the populations of lower and lower-middle-income countries of the international division of production and labor, the unequal opening of nonindustrialized countries to capital and exports from developed countries, intense and uncontrolled flows of financial capital, and the global spread of severe environmental problems and behavioral patterns that constitute globalization is highly contradictory. Globalization of international trade has largely facilitated the expansion of already strong economies and increased the marginalization of weak economies through the inappropriate application of market policies in countries lacking the necessary conditions for trade liberalization. This has led to rising global social and health inequalities over past decades. For example, the World Commission on the Social Dimension of Globalization (2004) has shown that the ratio between the richest and poorest countries has increased from 53.9:1 to 121.1 over the past 40 years, and income inequality has increased for 59% of the world’s population.

Implications For Workers’ Health And Safety

Fiscal policies fostered under globalization have been typically associated with adverse consequences for social cohesion and for occupational and environmental health in developing countries. Structural adjustment programs have largely led to declining public sector employment and an increasing preponderance of low-quality jobs with few career advancement prospects. Increasing fluidity of global production and markets has facilitated the transfer of obsolete production technologies, posing hazards to both working and nonworking populations. Moreover, pressures to limit regulatory protections at the workplace to enhance labor market ‘flexibility’ have been widely promoted in developing countries as essential to attract foreign direct investment, and have further accelerated the decline in attention to health and safety for working populations. Brown (2005) points to the experience of free-trade zones (FTZs) such as the maquilladoras in Northern Mexico as illustrating that labor market ‘flexibility’ is often a pretence for minimalist regulation, anti-union measures, and unsafe working conditions. Ironically, lowered costs due to labor market ‘flexibility’ have driven a shift of production and services away from developed to developing countries, often at the expense of jobs and/or protections (such as rights to participation, right-to-know, right to refuse hazardous work) for workers in developed countries.

An important mechanism by which these impacts have occurred is through constraints placed on government capacity to regulate in the interests of health, both through loan conditionalities imposed by large lending institutions and through free trade agreements, which may have an impact on the setting of public health standards, nationally and internationally. For example, the Global Agreement on Trade and Services (GATS) has brought health-care services into the ambit of a free market in ways never previously experienced and often under conditions not anticipated by national governments. As a result, publicly funded health systems based on equity and access, critical to the health sector in many developing countries, are under threat, whereas international trade agreements facilitate international mobility and growth of private health care, thereby potentially threatening the realization of the right to health.

In the occupational setting, trade agreements, such as those made at the World Trade Organization (WTO), present serious challenges to the future of the precautionary principle. This is despite its adoption at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in 1992 and its relevance for worker protection where considerable uncertainties remain in the risk assessment process. Decisions emanating from the WTO on trade in asbestos products and beef from hormone-treated cattle have given little confidence that protection of workers’ and community members’ health will serve as sufficiently cogent reasons for restrictions on trade where uncertainties cannot be answered by traditional risk assessment methods. Pressures on developing countries to accept hazards that are rejected in many developed countries stem from economic dependency and unfair terms of trade, aspects which the WTO has steadfastly failed to address. Indeed, experience in the field of genetically modified (GM) foods has shown that producers perceive developing country consumers to be more accepting of new technologies due to greater levels of trust in regulation, positive perceptions of science, and favorable media influence. Further, in contexts in which civil society organization is weak and democratic governance traditions poorly developed, opportunities for popular influence over standard-setting or for national governments to assert independence in protecting health and safety standards at work may be severely limited. This problem has been highlighted in Central American trade negotiations by Rosenthal (2005) with regard to pesticide regulation and the role played by pesticide companies in subverting restrictions on highly hazardous chemicals and undermining public health protections.

However, global integration has meant more than just economic integration. Globalization has provided the opportunity for significant advances in terms of health, notwithstanding its ambivalent record in terms of economic development. For example, globalization has contributed to the dissemination of human rights norms, widespread adoption of information technologies, and employment opportunities for women in work from which women were traditionally previously excluded. Diffusion of new developments in cleaner production technologies that generate less waste and promote environmental sustainability stand in contrast to the traditional flow of hazardous technologies to poorer countries. Moreover, as pointed out by Weissbrodt and Kruger (2003) and Amnesty International (2006), globalization has also created the possibility of upward harmonization of labor standards to improve working conditions for employed populations in developing countries.

Increasing Forms Of More Hazardous Production

Nonetheless, the World Health Organization’s Global Plan of Action on Workers’ Health (2006) reflects concerns that double standards on the part of multinational companies may encourage them to take advantage of lax (or nonexistent) regulatory frameworks and weak labor organization to shift hazardous industrial production processes to developing countries.

For example, the mining of crocidolite asbestos from the end of the nineteenth century in Southern Africa, the failed reprocessing (more accurately, dumping) of mercury waste by a UK-based company, Thor Chemicals, in South Africa, and the export of the sterilant nematicide DBCP to banana plantations in Costa Rica, are all cases in which export was allowed to take place at a time when the hazards of these agents were well-recognized in the countries of the parent companies. In all three settings, workers from developing countries, unprotected by their national regulatory frameworks, suffered tremendous burdens of work-related mortality and morbidity. In the case of Thor Chemicals, Butler (1997) showed how this was exacerbated by the casualization of production, resulting in poorer monitoring and follow-up of workers, and under-ascertainment of the true health impacts. Not surprisingly, the record on holding those responsible accountable for their actions is slim. The effectiveness of international conventions to control the transfer of hazardous technologies, such as the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal and the Rotterdam Convention on Prior Informed Consent for trade in hazardous chemicals and pesticides is hugely contingent on national and international political will, under circumstances in which workers’ health may be over-ridden by the influence of powerful vested interests.

Increased forms of hazardous production may also arise indirectly as a consequence of changes in trade occurring with globalization, both in existing sectors and in new sectors. For example, London and Kisting (2002) showed that in Zimbabwe, the annual increase in pesticide usage more than doubled between 1991 and 1995 during a period of donor-imposed structural adjustment, while in Tanzania, liberalization of trade policy led to large increases in pesticide imports, an 80-fold proliferation of private retailers, and involvement of children in the retailing of pesticides. Tobacco farmers in Latin America have been reported to have been locked into a spiral of debt and pesticide poisoning through loan agreements to repay the increasing quantity of pesticides purchased for tobacco production. Despite the existence of programs to promote ethical trade, multinational companies’ control of food markets appears to have pushed developing countries’ farmers into production that requires higher inputs, including potentially hazardous pesticides, fertilizers, and genetically modified crops.

In addition to established sectors such as agriculture, globalization has led to expansion of production in exportlinked sectors, such as chemical, electronic, and biotechnology industries, thereby adding new hazards to those already prevalent in developing countries. The double burden of occupational disease parallels the experience of developing countries facing the epidemiological transition, characterized by high rates of morbidity from noncommunicable disease accompanying persisting high burdens of death and disability from acute infectious disease. Indeed, Rantanen et al. (2004) caution that the importance of major public general health problems (such as malnutrition, violence, TB, malaria, HIV, and infectious diseases) can act as a potential distracter from national willingness to address occupational hazards in developing countries.

Increasing Exposure Of Particularly Vulnerable Categories Of Workers

Expansion of international trade and globalization therefore has the potential to exacerbate existing inequalities and create new categories of vulnerability. Amnesty International (2006) points out that although groups traditionally viewed as vulnerable workers, such as migrants, women, and young workers, may have benefited from the extension of human rights norms globally, their working conditions may actually have deteriorated in practice.

For example, there is evidence that increased opportunities for women to work have been predominantly in manual dead-end jobs, including the most precarious and vulnerable work, thereby reinforcing gender inequalities in work. High levels of violence and abuse have been reported as a major occupational hazard among female street vendors in South Africa. Similarly, reports of violence and abuse against women continue to plague the floriculture industry, which has expanded rapidly in South America and East Africa over past decades, supplying flowers to northern hemisphere countries throughout the year. Employment in this sector is almost entirely dependent on the recruitment of young women into jobs with high potential exposure to neurotoxic and endocrine-disrupting chemicals, often working under conditions of extreme powerlessness.

Moreover, trade liberalization has typically targeted productive sectors where women’s labor predominates, and unfair competition from subsidized imports has led to steep declines in employment and therefore disproportionately undermined the livelihoods of women producers, for example, in the garment industry. In addition, women continue to carry the double burden of paid labor on the market and unpaid labor in the home. Indeed, women’s productive work is frequently an extension of the undervalued work they do in the home manifesting as work in the services sector or as lowly paid domestic workers in private homes.

Furthermore, it has been proposed that the growth in economic activity for women in poorly paying jobs may worsen household food security and increase risks of childhood injury and malnutrition. In some countries, the prevalence of child labor has not declined with globalization. Children continue to work in hazardous conditions in construction, agriculture, domestic service, and manufacturing industries in all continents and may be encouraged to enter areas of employment not previously open to young workers, such as described above with regard to pesticide retailing in Tanzania following structural adjustment policies. This is particularly exacerbated in countries with high burdens of HIV, where child-headed households may rely on paid child labor for their survival.

The process of globalization has therefore seen both a reduction in formal employment and an acceleration of the growth of informal sector employment in developing countries. Cornia (2001) estimated that by the mid-1990s, the informal sector constituted 58% of employment in Latin America, 74% in Sub-Saharan Africa, 43% in North Africa, and 62% in Asia. Unemployment is known to be bad for your health – so, too, is informal sector work. Lack of social security, often associated with extreme working conditions and almost nonexistent labor protection, characterize informal sector jobs. This is exacerbated by intensive competition and resultant higher levels of injury and disease. Occupational morbidity that occurs in the informal sector is typically invisible to national surveillance systems so is absent in data on the burden of occupational disease.

Because globalization has differentially displaced women workers from formal employment, women form the majority of workers in the informal sector. One of the consequences is that occupational morbidity and mortality among women is greatly underestimated worldwide. For example, estimates of the proportion of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) attributable to occupation risk factors have produced profiles that identify these risks as occurring typically among men (e.g., in excess of 80% for carcinogens and over 90% for injury risks) because they draw only on formal sector employment data. Yet considerable evidence exists that in both the formal and the informal sectors, women’s exposure to occupational hazards such as pesticides, hazardous chemicals, violence, and ergonomic hazards are substantially underestimated.

The vulnerability of workers in the informal sector is also emphasized by the downward migration of injured and disabled workers ejected from the formal economy (often as a result of inadequate health and safety protection) and the role it plays as a safety net for poor households’ income.

A further trend with globalization has been the growth of precarious work, which includes outsourcing, casualization, and subcontracting, all forms of externalization of production. Such shifts, largely related to a weakening in the bargaining power of labor, have been seen both within and across countries. For example, recent years have seen an increasing contracting and casualization in the mining sector and an expansion of home-based production in the clothing industry in South Africa, both industries with long-established traditions of formal employment and significant levels of worker unionization. The World Health Organization (2006) has noted that, even within developed countries, declines in public sector employment, expansion of precarious work, and expansion of the most hazardous forms of production among migrant workers have been evident.

Externalization places the control of workplace hazards largely in the private domain beyond the effective reach of regulation, undermines trade union actions to protect health, and reduces production costs for employers, with adverse implications for occupational health and safety. It largely shifts the responsibility for safety onto unregulated contractors or onto the worker herself, who is often subject to piece work incentives that are contradictory to health and safety. Outsourcing has therefore been associated with production in cramped and unsuited work environments, outmoded and unguarded machinery, poor ventilation, and little or no personal protective equipment or training.

Piece-work leads not only to greater physical, chemical, and biological hazards because of workers’ concerns to maximize production and hence income, but also increased job stress and job insecurity, both predictors of health status. London and Kisting (2002) highlight evidence from Brazil suggesting a link between women’s participation in informal sector work and mental health impacts, and McDonough (2000) showed that job insecurity predicted health status and psychological distress, even when controlled for job stress, degree of control in the job, level of exertion, and strain. Likewise, Cornia (2001) drew links between the instant liberalization experienced in the countries of the former Soviet Union and subsequent psychological impacts on workers related to feelings of humiliation and hopelessness. Ironically, Sass (2000) pointed out similar kinds of emotional impacts reported among Costa Rican banana plantation workers poisoned by the pesticide DBCP who were seeking redress and compensation. McDonough (2000) describes the work environment, specifically the increasing insecurity of work, as analogous to a toxic agent ‘‘because it erodes the view of the self as an active agent capable of purposive action to meet desired goals.’’

Responses To Hazards – Limitations And Opportunities For Occupational Health Services

Occupational Health Services

The World Health Organization (2006) argues that to respond adequately to the changing global context for workers’ health it is important to recognize the need to integrate OHS with broader public health and health promotion services. Traditional OH frameworks that originate in developed countries frequently focus only on workplace hazards and their control, and are often suited to large companies with an educated and organized workforce. Such models may perform poorly in developing country settings, where a large informal sector exists and where environmental routes of exposure involving both workers and community members may outweigh occupational exposures. Moreover, the heavy background burden of both communicable and noncommunicable disease in developing countries points to the need to integrate occupational health into models of primary health care appropriate to countries of different economic development.

Regulatory Frameworks

There is a paucity of research in developing countries addressing occupational health and particularly the vulnerabilities generated by new international economic and trade relationships. Rantanen et al. (2004) point out that whereas 80% of the world’s working population live in developing countries, only 5% of occupational health research takes place in these countries. Regulatory frameworks in developing countries therefore lack a strong research base and suffer from a reliance on risk assessments conducted in northern hemisphere settings, which may be of only marginal relevance for local conditions. This is particularly evident in relation to pesticides, whose conditions of use in developing countries are more hazardous, where subcontracting exacerbates the lack of safety controls, and where high levels of comorbidity (e.g., malnutrition, HIV, infectious diseases) in working populations in developing countries exacerbate the risks from workplace exposure considered ‘safe’ in developed countries. Most developing countries continue to rely on the World Health Organization’s classification of pesticide hazards for their regulatory framework, despite the long-time recognition that this system severely underestimates risks for chronic adverse health impacts. The use of many pesticides banned or restricted in developed countries still occurs in developing countries for reasons of low cost, lack of institutional capacity for regulation and enforcement, and lack of awareness.

Hazard Communication And Developing Countries

The use of labeling and safety data sheets to communicate hazard information about chemicals is viewed as essential for protecting health at the workplace globally and frequently forms the center of national health and safety legislation in many countries. However, experience in a number of developing countries has demonstrated poor comprehension of hazard symbols and information. Expectations that workers’ increased understanding will result in behavior change overlook both the social construction and cultural specificity of interpretations of risk. Ironically, rather than protect workers, hazard communication tools may then lead to a paradoxical increase in risk because of assumptions that workers could and should be responsible for behaving safely. This is well illustrated in the promotion of safe use of pesticides by the pesticide industry whose emphasis on farmer training has not seen a significant reduction in the extent of pesticide poisoning among rural agricultural workers worldwide over the past 40 years. Indeed, far from being ignorant of pesticide hazards, there is considerable evidence that farmers in developing countries are well aware of pesticide hazards but handle pesticides in hazardous ways because of structural factors beyond their immediate control. If poorly targeted and untested, hazard communication materials may therefore become a substitute for safer design and cleaner production or may provide a false sense of security to both users and regulators.

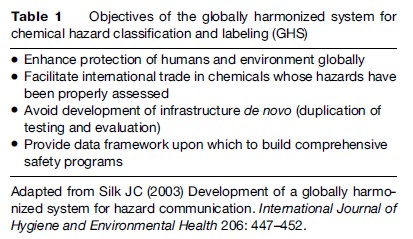

Nonetheless, the absence of uniform labeling practices remains a major source of risk for workers in developing countries, where requirements for hazard information on labels and Safety Data Sheets (SDSs) may be substantially lower than that exercised in parent countries of companies exporting hazardous chemicals to developing countries. Silk (2003) describes recent global efforts to harmonize the classification and labeling of pesticides as an attempt to establish global standards for both the classification of chemical hazards and how such information should be effectively conveyed to exposed groups. The intended purpose of the GHS includes promotion of safety in relation to chemicals but also to facilitate trade by harmonizing registration and labeling requirements across countries (Table 1). However, in the absence of effective mechanisms to ensure adequate training and understanding of hazard symbols and related information, the GHS risks facilitating trade in hazardous chemicals at the expense of protecting the health of workers and consumers handling chemical products.

As a complement to upstream strategies, such as the development of cleaner production technologies, or, in the case of pesticides, Integrated Pest Management or Pesticide Reduction policies, hazard communication can play an invaluable role. Alone, however, reliance on hazard communication runs the risk of exacerbating risks for working populations from hazardous chemicals.

Human Resources

Economic policy reform under globalization has also been synonymous with cutbacks on government spending and reductions in employment levels of public servants. Yet the control of occupational hazards requires a suitably qualified human resource base, particularly in developing countries where globalization has driven the expansion of sectors that are particularly difficult to regulate (viz., informal sector and precarious work). Rantanen et al. (2004) argue that the ‘brain drain’ of occupational health professionals from developed to developing countries remains a key concern and this will have been exacerbated by the impact of HIV on the workforce of developing countries most affected by AIDS. Even though data on the pull and push factors specific to occupational health professional migration is scant, there is little reason to believe that occupational medicine and hygiene practitioners would be any different than colleagues in other health-care settings, who have left unsafe, unrewarding, and poorly remunerated jobs and moved in large numbers to countries of the north. Given the role of OHS in maintaining workplace productivity, failure to invest in occupational health capacity and retain human resources for occupational health will have adverse implications, not only for human health and the environment, but also for sustainability of economic development. These effects are experienced in precisely those countries with the most vulnerable economies in our globalized environment.

Surveillance

Although surveillance is key to estimating the extent of workplace hazards and identifying prevention strategies, surveillance systems for occupational injury and illness are often incomplete, poorly coordinated, or entirely lacking, particularly in developing countries, where hazards and risks are highest. Many health-care providers are not aware of occupational hazards, particularly those experienced in nontraditional workplace settings. This has meant that the burden of disease arising from occupational hazards associated with globalization has remained largely invisible. Examples of efforts to address these gaps have been initiated by international agencies as multicountry surveillance projects to estimate the burden of disease from acute pesticide poisoning and from silicosis.

The consequence of inadequate surveillance data is substantial. All too frequently, the absence of any evidence for an adverse effect of an occupational or environmental exposure is regarded as evidence of absence of any effect, as a result of which regulatory decisions may fail to protect workers and communities. Wesseling et al. (2006) demonstrated the importance of using surveillance data on acute pesticide poisoning to inform regulatory decisions with regard to pesticide registrations in Central America, and van der Hoek and Konradsen (2006) have highlighted similar experiences in Sri Lanka, where regulatory interventions on highly hazardous pesticides have resulted in a decline in deaths due to pesticide poisoning. Moreover, biases in surveillance may disadvantage particular vulnerable groups, such as women and migrant workers. Absence of data from good surveillance of occupational disease and disability has contributed to the externalization of the real costs of hazards at the workplace and has probably facilitated the transfer of hazardous technologies.

Trade, Economic Policy, And Health

Inasmuch as unfair conditions of trade can put downward pressure on occupational health standards, globalization can also be harnessed to the reverse. For example, norms and standards for multinational companies provide opportunities for civil society monitoring and oversight, and can complement collective agreements between trade unions and employers that protect worker health and safety. Although voluntarist systems for accrediting fair trade and employment have the potential to undermine statutory regulations and the sustainability of government-run protections, their existence often helps drive upward the prevailing view of what industry can achieve, and so are helpful as a framework for advocacy and lobbying. Even in the arena of donor grants and trade agreements, it may be possible to strengthen workers’ rights to health and a safe environment by, for example, linking adoption of ILO conventions related to health and safety to these agreements. Of course, political willingness to explore social policies that prioritize vulnerable groups, including workers, is key to the implementation and success of such strategies.

HIV/AIDS At The Workplace – A Global Challenge

The HIV/AIDS epidemic represents one of the most profound challenges to human well-being of all time. Of the 39 million people living with HIV, over 90% are of working age and over 60% are labor force participants. Most workplace concerns relate not to occupational transmission (which may rarely occur in very specific high-risk jobs such as sex work or health-care provision with blood contact) but more generally, because workers are members of a broader community with existent risk factors. Inasmuch as the organization of work may increase social risks for HIV transmission, such as, for example, in the role played by migrant labor in increasing vulnerability to HIV, it should be recognized that the workplace is a key site for addressing HIV. Indeed, London and Kisting (2002) raise the question that it may well be ethically appropriate, under such circumstances, to consider HIV to be an occupational illness deserving of compensation. However, such considerations should not be mistaken for assuming the possibility of workplace HIV transmission.

Initiatives to introduce workplace HIV testing may therefore be seriously misguided if premised on presumptions of preventing HIV transmission or establishing fitness for work, since a positive HIV test alone tells little about a workers’ capacity to do a job, and is of little prognostic value in determining future ability, particularly with increasing availability and success of anti-retroviral (ARV) treatment. Past examples of badly planned and misinformed efforts to mandate HIV testing for workers have illustrated how HIV testing may lend itself to increased levels of discrimination at the workplace. Indeed, for many vulnerable occupational groups such as migrant workers, HIV testing and exclusion from work remains a serious problem in a number of countries.

This is of particular relevance to global plans to advance access to ARV treatment. Fear of stigma and discrimination and potential dismissal is one of the major barriers to early uptake of voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) and enrolment in ARV treatment programs. Creating a non-discriminatory work environment requires both a national legal and policy framework that prohibits discrimination, and the presence of workplace policies that are jointly agreed upon by employers and workers and informed by the rights-based approach of the International Labor Office (ILO) code of practice on HIV/AIDS. Successful examples of adoption have helped expand ARV provision and care in many developing countries through joint public-private initiatives. The success of such programs is largely related to ensuring confidentiality, since, in the current climate of globalization, job insecurity remains a major concern that potentially undermines HIV prevention measures.

However, recent debates about the introduction of ‘routine’ testing at health facilities in countries most affected by HIV have illustrated that there are underlying tensions within approaches to HIV control, and is evidence of a backlash against what are perceived to be obstacles placed by rights-based approaches to more traditional population-based methods that limit individual autonomy and community choices. To some extent, these calls reflect an understandable desperation in the face of the failure of existing strategies to address HIV and a belief that ‘routine’ testing could help address problems of stigma. However, particularly for working populations, moves to limit rights-based protections in HIV control could be disastrous if they open the door to workplace victimization.

Addressing workplace stigma may be far better achieved through effective health promotion and the workplace may be an excellent site for effective HIV/AIDS interventions that address both prevention and treatment. The experience of many employers and employees in countries most affected by the epidemic are an important guide to models of HIV prevention in developing countries. For example, HIV prevention programs on South Africa’s gold mines have pointed to the critical importance of peer counseling and theoretically grounded models for behavior change essential for effective HIV control. Workplaces thus represent not only opportunities for production but also for sites for education and prevention in relation to HIV and workplace hazards.

Moreover, as the groundswell for ARV access gains global momentum, large employers have provided much of the data for cost-effectiveness and operational efficiency of different models of ARV provision. Cooperation between labor, employers, and government in both prevention and treatment of HIV has proven to be a key component of developing models for expansion of HIV care and support.

Central to the success of addressing HIV at the workplace is the effectiveness of occupational health and safety structures. Where HIV/AIDS are integrated as part of a health and safety agenda, stigma and discrimination can be addressed more effectively in that HIV/AIDS become ‘de-exceptionalized’ as simply one of a number of health and safety concerns. Indeed, compared to routine testing, mainstreaming HIV into OHS delivery may be both more protective of workers’ rights and a far more effective method to address stigma. If, however, occupational health structures are poorly organized, opportunities for effective HIV prevention and treatment programs become impossible. Experience has shown that, in several high-prevalence settings, availability of occupational health services has made significant contributions to both HIV/ AIDS prevention and treatment programs, as well as providing access to tuberculosis (TB) treatment, which, given the comorbidity of TB and HIV, has helped to sustain gainful employment. Many workplace programs have also extended treatment to family members of employees, frequently female spouses, or to selected groups in communities, such as pregnant women, as part of their integration in national HIV control efforts, thus illustrating the importance of gender sensitivity in occupational health programming. The recent proposed program for Basic Occupational Health Services by the WHO (2006) is therefore of great significance, not only in signifying a standard to address occupational hazards that arise directly from workplace exposures but also to address the health and safety of workers generally, and, in consequence, the productivity of working populations, instrumental to poverty alleviation and sustainable development. The elaboration of the ILO Code of Conduct on HIV into an international standard would further accelerate the process of using global governance to harmonize upward international standards to protect workers’ health and safety.

Conclusion

In all these initiatives, meaningful cooperation between labor, employers, and government is key to addressing HIV at the workplace, as it is in addressing hazards that arise directly as occupational exposures. Establishing trust between occupational health services and workers is contingent on two key aspects – first, demonstrating evidence of professional independence by OHSs from third party influences, particularly employers, in clinical decision making and in implementing programs to protect workers’ health and safety, and, second, in recognizing workers who are at risk for occupational injury and illness as partners in improving OHS at the workplace.

Ethical practice by occupational health practitioners that reflects upward harmonization of standards across countries and solidarity of professional associations around these standards could assist in addressing the problem of dual loyalty faced in balancing the practitioner’s obligation to the health of workers and the potentially divergent interests of employers in relation to health and safety at the workplace. Indeed, the sine qua non for successfully addressing workers’ health and safety in the current context of globalization must revolve around upward harmonization of health and safety standards, rather than allowing globalization to dictate the terms of a ‘race to the bottom.’

Moreover, international health and safety agencies have a key role to play in ensuring that the processes for setting standards are transparent, independent, and based on the best evidence. Contestation around safety standards in developed economies and at the international level has major ramifications for many developing countries, which usually lack institutional capacity to develop standards and provide oversight over standardsetting processes, and so borrow heavily from international standards. Where such international standards are subject to corporate or third-party influence, adverse consequences for the health of workers in developing countries are substantial.

Given the impact of trade agreements on workers’ and population health, leadership from international agencies should help define approaches that prioritize and protect health from being subjugated to the interests of the market. Moreover, international occupational health research agendas must include timely and action oriented surveillance for the impacts of global economic and trade reforms on workers’ health and safety. Efforts to harmonize health and safety standards globally should place the human rights of workers, their families, and communities at the center of policy considerations, in ways that increase their capacity individually and collectively, to make independent decisions affecting their health and safety.

Bibliography:

- Amnesty International (2006) Human Rights, Trade and Investment Matters. London: Amnesty International.

- Brown GD (2005) Protecting workers’ health and safety in the globalizing economy through international trade treaties. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health 11: 207–209.

- Butler M (1997) Lessons from Thor Chemicals. In: Bethlehem L and Goldblatt M (eds.) The Bottom Line – Industry and Environment in

- South Africa, pp. 194–213. Cape Town, Africa: University of Cape Town Press.

- Cornia GA (2001) Globalisation and health: Results and options. Bulletin of the World Health Organisation 79: 834–841.

- London L and Kisting S (2002) Ethical concerns in international occupational health and safety. Occupational Medicine 17: 587–600.

- McDonough P (2000) Job insecurity and health. International Journal of Health Services 30: 453–476.

- Rantanen J, Lehtinen S, and Savolainen K (2004) The opportunities and obstacles to collaboration between the developing and developed countries in the field of occupational health. Toxicology 198: 63–74.

- Rosenthal E (2005) Who’s afraid of national laws? Pesticide corporations use trade negotiations to avoid bans and undercut public health protections in Central America. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health 11: 437–443.

- Sass R (2000) Agricultural ‘‘killing fields’’: The poisoning of Costa Rican banana workers. International Journal of Health Services 30: 491–514.

- Silk JC (2003) Development of a globally harmonized system for hazard communication. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health 206: 447–452.

- Van der Hoek W and Konradsen F (2006) Analysis of 8000 hospital admissions for acute poisoning in a rural area of Sri Lanka. Clinical Toxicology 44: 225–231.

- Weissbrodt D and Kruger M (2003) Norms on the responsibilities of transnational corporations and other business enterprises with regard to human rights. American Journal of International Law 97: 901–922.

- Wesseling C, Corriols M, and Bravo V (2005) Acute pesticide poisoning and pesticide registration in Central America. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 207: 697–705.

- World Commission on the Social Dimension of Globalization (2004) A Fair Globalization: Creating Opportunities for All. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labor Office.

- World Health Organization (2006) Global Plan of Action on Workers’ Health 2008–2017: Draft for External Consultation. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

- Buss PM (2002) Globalization and disease: In an unequal world, unequal health! Cad Saude Publica 18: 1783–1788.

- Grandjean P (2004) Implications of the Precautionary Principle for primary prevention and research. Annual Review of Public Health 25: 199–223.

- International Labour Office (2001) The ILO Code of Practice on HIV/AIDS and the World of Work. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Office.

- Kishi M and Ladou J (2001) International pesticide use. Introduction. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health 7: 259–265.

- Koivusalo M and Rowson M (2000) The World Trade Organization: Implications for health policy. Medicine, Conflict and Survival 16: 175–191.

- Ladou J (2003) International occupational health. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health 206: 303–313.

- Ladou J (2005) World Trade Organization, ILO conventions, and workers’ compensation. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health 11: 210–211.

- Loewenson R (2001) Globalisation and occupational health: A perspective from Southern Africa. Bulletin of the World Health Organisation 79: 863–868.

- London L and Bailie R (2001) Challenges for improving surveillance for pesticide poisoning: Policy implications for developing countries. International Journal of Epidemiology 30: 564–570.

- London L, de Grosbois S, Wesseling C, et al. (2002) Pesticide usage and health consequences for women in developing countries: Out of sight, out of mind? International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health 8: 46–59.

- Murray DL and Taylor PL (2000) Claim no easy victories: Evaluation of pesticide industry’s global safe use campaign. World Development 28: 1735–1749.

- Partanen TJ, Hogstedt C, Ahasan R, et al. (1999) Collaboration between developing and developed countries and between developing countries in occupational health research and surveillance. Scandinavian Journal of Work and Environmental Health 25: 296–300.

- Quinlan M, Mayhew C, and Bohle P (2001) The global expansion of precarious employment, work disorganization, and consequences for occupational health: a review of recent research. International Journal of Health Services 31: 335–414.

- Sinclair S (2005) The GATS and South Africa’s National Health Act. A Cautionary Tale. Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

- Westerholm P (1999) Challenges facing occupational health services in the 21st century. Scandinavian Journal of Work and Environmental Health 25: 625–632.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.