This sample Religion and Healing Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Religion is one of the most pervasive factors influencing values, moral experience, and social organization, as well as concepts of health, illness, dying, and death. Western academic disciplines, most assuming a separation of religion from the rest of life, provide disparate lenses that focus on selected aspects of people’s religious beliefs and practices. In contrast, South African activist researchers note that a number of African languages do not distinguish the terms religion and health. The Sesotho word bophelo, for example, includes Western notions of religion and health and extends to include not only the individual but also the social body. The alternate term ‘health worlds’ indicates the reality of ‘complex and increasingly mixed sets of ideas, signs, linguistic conventions, and cultural traditions and practices within which people live and by which they orient themselves’ (Cochrane, 2006: 69). This reorientation has much to offer in considering the significance of linking religion and healing in public health practice.

Definitional Challenges

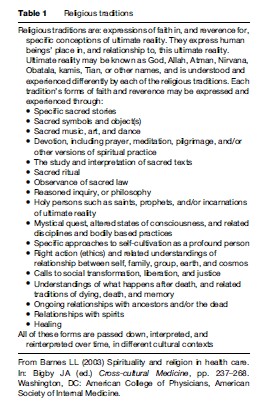

The Western concept of religion often lacks direct cognates in other languages, where human religious experience has emerged out of different histories, cultural contexts, and world views. Though the Latin etymology of the term is debated, the more widely accepted root religare, to bind, reflects the ways in which religious traditions have bound people and society together in relation to the sacred. First Roman Catholicism and later Protestant Christianity shaped a definition rooted in Christian experience that emphasizes a single divinity, a creed, specific codified beliefs, a scripture or scriptures, a formally recognized hierarchy of religious specialists (e.g., priests), prophets, centers of worship, forms of devotion, and rituals (in which sacrifice, if performed, is done symbolically). The assumption that Christianity represented the ideal form of religion led to comparisons and assessments of other so-called deficient or underdeveloped traditions. Emerging from critical shifts in comparative religious studies since the 1960s, a conceptual framework characterizing religious traditions as consisting of multiple possible characteristics in various combinations is illustrated by Table 1.

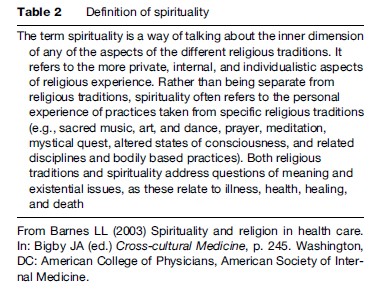

Increasingly, Western popular discourse and health science research have adopted spirituality as an alternative to religion, a polarization in which religion is viewed as primarily institutional, creedal, and ritually oriented, while spirituality is considered to be primarily individual, personal, and potentially mystical (an equally difficult term to define). An alternative definition of spirituality (Table 2), focusing on overlaps between the terms, may enable more fruitful cross-cultural comparisons for health research.

Individuals and groups regularly draw on religious traditions for explanations of suffering or illness. Medical anthropologists often refer to explanatory frameworks or models of illness within particular cultural groups. An explanatory model provides theories of causation, as well as expectations of duration, course, appropriate healers, and healing techniques related to an individual or group’s experience of illness. Classic taxonomies of these models by Murdock, Young, and Foster have sought to identify cultural tendencies toward naturalistic, supernatural, personalistic, impersonalistic, externalized, or internalized explanations of illness and concomitant healing and health behaviors. The place, role, and aspects of religious identity and practices in these taxonomies, and the particular dimensions of explanatory models emphasized, rest on cultural assumptions about both religion and health. Additionally, when seeking to understand the health world of individuals, social institutions, or entire populations, public health workers must be cognizant of how their own explanatory models of illness intersect with others’ models.

Religious Studies’ Approaches To Religion And Healing

The field of religious studies, itself drawing on multiple disciplinary orientations, conceptualizes the link between health and religion – or religious traditions – in two primary ways. The first focuses on the interpretation, or exegesis, of primary texts with content related to healing. The second addresses lived phenomena involving practices and worldviews with direct and indirect bearing on the health of individuals and communities.

Any discussion of religion and healing must include questions of ultimate meaning and various understandings of the sacred or divine, afterlife or reincarnation, cosmological explanations of human suffering, and multifaceted models of what it is to be human. Explanatory models of illness often identify deeper reasons for suffering (e.g., a test or punishment from God or other sacred force, an opportunity to emulate specific paradigms of suffering), which may reinforce right or moral health behaviors; or which may require specific religious actions to redress. Theological diversity within a tradition may inflect health worlds differently; in many parts of Latin America, liberation theologians promote public health and welfare by confronting structural violence, while other Christians turn to faith-healing practices and post-death salvation to the neglect of structural and public health issues.

Illness itself may be not only a category afflicting an individual, but also a group, and may include the effects of structural forms of intergroup violence. Healing interventions may require religious rituals of different kinds. Rituals intended to effect healing may be formal and performed by elite specialists, like a priest (Sp. cura, one who heals) or shaman; they may be home-based, undertaken by laymen or laywomen. These practices vary depending on the gender, social class, racial or ethnic background, immigrant status, or other social variable of patient identity, their social networks, and the practitioners whose help they seek. Outcomes may be intangible, sometimes occurring after death. Although physical cure may stand out as evidence of the power of the practice, it is far from the only result sought – a core difference from other kinds of outcome and efficacy criteria. Various scholars and religious reformers have argued that Islamic ablutions, Hindu purity regulations, Jewish kosher laws, and other religious practices have their origins in, or at least may be rationalized as, health promotion movements, but such explanations do not address the symbolic meaning these practices now hold in their practitioners’ daily lives. Moreover, insofar as various medicine systems intersect deeply with religious traditions – Tibetan or Ayurvedic medicine being only two examples – the Cartesian dualism of the very categories religion and health fails to do justice to the complexity and interdependence of religious and health worldviews.

Biomedical Approaches

Biomedicine approaches the relationship between religion and healing from a number of perspectives. The first involves the religiously informed bioethical dilemmas that arise in relation to medical decision making, sometimes in relation to religiously based prescriptions or prohibitions of actions or substances. The most routinely cited are the rejection of blood transfusions by Jehovah’s Witnesses and of biomedical interventions by practitioners of Christian Science. In such cases, religion is represented primarily as an unscientific obstacle to biomedical therapies, and not as a source of healing in its own right.

Some of these bioethical debates are driven by the impact of technological innovation, rather than ethics informing the development of technology. Rather than reflecting the pluralism within religious traditions, bioethics tends to present traditions as having generic and normative ideals for correct action, rooted in the interpretation of authoritative sources. This focus bypasses accounts of the customized, lived ways in which individuals and communities actually integrate authoritative rulings (to the extent they are aware of them) with other factors, when making ethical decisions in particular social and personal contexts.

Another approach focuses primarily on quantifiable health outcomes and on the less tangible factor of religious coping in the face of illness or other forms of suffering. Although individual biomedical physicians may craft a host of personalized ways to integrate their religious lives with their medical practice, biomedicine as a discipline has resolutely distanced itself from religion, which has been framed as antithetical to science. Yet not all researchers have accepted the mutual exclusiveness of the two domains. Some have applied medical research models to the impact of religiosity on health, in the hope that by employing standards of research and evidence most familiar to, and accepted within, biomedical culture, their colleagues may become less reluctant to acknowledge and build on links between the domains.

This undertaking has posed the challenge of formulating an operationalized definition of religiosity that can be articulated through scales. Many such scales have focused on religious affiliation or membership, religious participation or attendance at formal services, private religious practices (e.g., prayer, meditation, reading sacred literature), and religious coping in response to difficult circumstances. Critics argue that few of these scales truly represent religious pluralism, reflecting instead the often Christian orientation of their designers. Such scales are well suited for the study of some Christian communities, but fall short when investigating most other religious traditions. Alternate approaches might, for example, focus on ritual, the observance of prohibitions and prescriptions, and other dimensions of practice.

Medical literature, professional education, and policy initiatives have increasingly taken note of cultural and, occasionally, religious pluralism. Transcultural psychiatry, for example, represents an attempt to critique biomedical disease categories and apply medical anthropological insights into illness experiences that often have religious or spiritual dimensions. Medical anthropological, ethnographic, and cross-cultural studies regularly include analysis of religious healing practices. Here, however, sociological, political-economic, or psychological models of religion tend to prevail, many of them relatively reductionistic.

Biomedical approaches have also examined ways in which religiosity may serve as a protective factor against negative health outcomes. Examples include ways in which religious communities may help individuals internalize healthy lifestyle choices and provide external sanctions for violating norms. Religious coping strategies and patterns of mutual economic and social support likewise receive attention. Some links between various indicators and specific coping strategies have been suggested, but variables of social location, types of health problem, as well as the diversity and changeability over time of religious orientation limit their predictive value and generalizability. Critics often challenge the design of such studies and argue that few clinicians have adequate training to serve in the capacity of spiritual advisor or counselor, particularly in the face of growing religious pluralism.

The rise of biomedicine not only in the West, but also around the world, has led to its routinely being referred to simply as medicine. Yet this apparent triumph of a single system belies the historical and contemporary pluralism of health worlds and healing practices in these same contexts. Few, if any, communities or cultures are homogeneous, whether in their religious traditions and practices, or in their approaches to health, healing, and related interventions.

In health decision making, multiple rationalities come into play, whether the outcomes be conceptualized as hierarchies of resort or patterns of resort. Whether such practices are characterized as folk, ethnomedical, traditional or, most recently, as alternative, complementary, or integrative, they reflect an underlying reality that many people routinely use multiple healing practices. Indeed, those who do not are often the exception. Some of these practices emerge from religious worldviews and traditions, whether overtly or less directly, although they are rarely included in the definitions of religiosity discussed above. Studies of complementary/alternative medicine (CAM) in the United States wrestle with whether or not to include practices such as prayer. However, by including prayer – whether personal or intercessory – the numbers of CAM users across demographic categories rise exponentially.

Increased data revealing significant disparities in disease burden, access, and outcome between patients, based on gender, class, race, and ethnicity, have led to initiatives to train clinicians to become culturally competent, capable of negotiating across differences in patient understandings of illness, health, and intervention. Yet the requisite skills and frameworks differ from other professional competencies, particularly insofar as they often entail addressing otherwise unexamined ignorance, indifference, and biases in relation to cultural and spiritual aspects of care. Although urban health-care institutions in the West have begun to recognize obstacles to appropriate care for religious minority patients who may face discrimination related to religious difference, the ongoing challenge remains one of not reducing culture or religion to lists of stereotyped traits.

Public Health Approaches

In the 1990s, WHO governing bodies considered proposals to amend the constitution’s definition of health to include spiritual well-being. The field of public health, though, shares many of the biomedical orientations to religion and healing. For example, attempts to identify positive and negative effects of religious practices and beliefs for the health of communities and larger populations parallel the biomedical focus on health outcomes. Epidemiological studies have shown a trend toward examining proximate risk factors for disease – those factors that are potentially controllable at the level of individual behavior – and away from distal or fundamental causes of disease – such as socioeconomic inequality and stressful life events – that put certain groups at risk of risks. This trend has been applied to inquiries into the roles of religion, health, and healing.

Proximate Variables Analysis

Since the late 1980s, the mechanisms linking religious commitment and behavior to health outcomes have come under scrutiny. Public health investigators have highlighted the effects of religiously driven restrictions on dietary and sexual behavior, and proscriptions of alcohol, tobacco, or drug use. Within this mechanistic framework, religious beliefs and participation are viewed as potentially promoting positive emotional states and exercise for health maintenance; and religious practices as potentially reducing stress and providing coping mechanisms. Conversely, religious involvement is also sometimes recognized as encouraging behaviors and lifestyle patterns detrimental to dominant definitions of health. If individuals violate a religious community’s norms (e.g., the resistance to condom distribution or medical abortion), they may be denied that community’s social resources, or even shunned. Religious organizations may provide paternalistic forms of care or exploit vulnerable individuals as well. Some religious worldviews may assign moral responsibility for a disease to the individual, prevent some from seeking medical care, or increase guilt, shame, and anxiety in relation to mental illness, thereby intensifying its burden.

There are significant limitations to the proximate variable analysis approach for health promotion. In particular, it risks instrumentalizing religious traditions, such that the multiple goals of religious practice, as well as alternate notions of efficacy, may be overlooked altogether. Health promoters and biomedical providers alike may exploit specific practices or convictions in order to secure agreement or compliance with an intervention, and overlook the broader ways such practices or orientations fit into, and serve, the larger community and tradition.

Social-Inequality Analysis

The roots of the early public health movement owe much to Christian medical missionary work in the developing world and to European and American social gospel movements of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Even in the first decade of the twenty-first century, 30–70% of the medical infrastructure in sub-Saharan Africa remains in the hands of faith-based organizations (FBOs), the descendants and offshoots of early medical missions. The challenge now for global health and development work is to understand the roles these organizations play in the lives of their communities and to identify both constructive and critical approaches to collaboration.

Religious traditions provide their adherents with both explanatory models ‘of ’ the world (how it is) and visionary models ‘for’ the world (how it ought to be). Orientations toward ultimate human possibility – whether in this world/life or a subsequent one – often provide the motivation from which to address issues of social injustice and inequality. Value orientations toward service, and toward advocacy for social justice and responsibility, frequently complement and support a community’s public health. At the same time, even within a given tradition, religious orientations may provide a justification for the status quo and continued inequality as expressions of divine will or sacred order. The responses of Christian churches and denominations in the United States to slavery, women’s suffrage, civil rights, homosexuality, and immigration illustrate ethical and interpretive diversity within a religious tradition. In other settings, Hindu responses to caste inequality, Muslim responses to religious minorities, and Jewish responses to racial minorities within Jewish communities have been equally diverse.

Discrimination on the basis of religious affiliation is a significant but often unrecognized aspect of religion and health. Minority cultural groups confront specific forms of individual and social suffering, and may be the targets of various forms of bias that contribute markedly to the burden of disease, both mental and physical. The experiences of racial, ethnic, linguistic, or religious minorities often shape the types of interpretation, expression, and practices of religion to which they turn. Social marginalization and the experience of prejudice likewise affect access to existing health-care services in every society. The very structures and forms of care may inadvertently privilege certain religious communities over others, with health workers often unaware of the social suffering experienced by some religious minorities. The rise of Islamophobia in Western societies, for example, illustrates that religious discrimination can take both direct and indirect forms and may be present at individual, institutional, and structural levels.

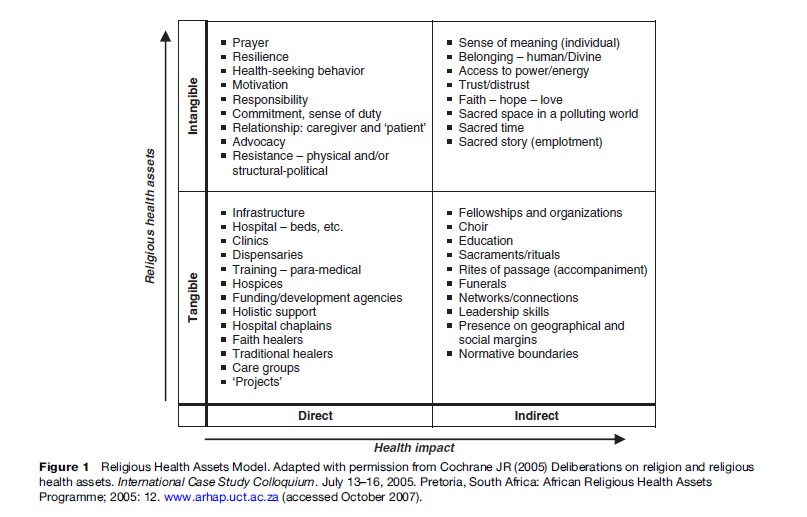

The shift in development studies from a deficit to an assets orientation is reflected in a religious health assets model that has arisen in South Africa in response to the HIV/AIDS crisis. This model recognizes that religious communities frequently have multiple ties at the local, regional, national, and transnational levels. Their social capital can enable sustainable public health efforts that are flexible and responsive to local communities.

Some public health projects operate within faith-based organizations. Congregations and larger groupings of FBOs may host health screenings for diabetes or hypertension, maternal and child health programs, community mental health counseling training, and advocacy initiatives for health policy changes. Clergy and other leaders regularly function as advocates for social and health related behavioral change. Religious organizations and leaders bring considerable experience and insight into the health of their communities. However, they often lack the tools of public health economists to assess their own needs and assets. Public health initiatives likewise must wrestle with how to address cultural and religious practices in faith communities that may adversely affect public health.

Cochrane proposes an analytical table for understanding religious health assets, taking into account both the direct and indirect, tangible and intangible assets for the health of a community (Figure 1). From this perspective, the direct tangible assets for public health – in the form of medical facilities, personnel, and financial resources, for instance – are only the tip of the iceberg. Religious entities may have some unique added value (and deficits) in more indirect and intangible ways. Public health work builds on the leading causes of life that often emerge in religious communities: Agency, connection, coherence or meaning, intergenerational support, and hope. A more complicated question involves how to assess the intangible and indirect health effects of religious activities, organizations, and informal networks.

Conclusions

Religion and health are multidimensional categories, such that considering their relationship becomes a daunting exercise. In order to understand how religion is conceptualized in relation to public health, we must consider the multiple ways in which people express and experience their faith and reverence. Many of these are also health practices and shape the strategies people utilize in maintaining health, diagnosing ‘disease,’ and managing illness. The religious health assets of communities may also include intangible capacities of local knowledge and affective resources to motivate, mobilize, and provide relational ties and support to individuals and communities in crisis.

Approaches focusing on health beliefs suffer all too often from the indirect exporting of a religion-as-beliefs model and the misrepresentation of both religious traditions and orientations toward health and related practices. The proposal to consider healthworlds in which multiple explanatory models, often including biomedicine, operate, and in which individual and community religious resources for health are mobilized, represents an extension of the meaning-centered model of patient care proposed by medical anthropologists. The challenge remains to integrate complex, religiously informed healthworlds with the models and practices of public health in ways that do justice to both.

Bibliography:

- Barnes LL (2003) Spirituality and religion in health care. In: Bigby JA (ed.) Cross-cultural Medicine, pp. 237–268. Washington, DC: American College of Physicians, American Society of Internal Medicine.

- Cochrane JR (2006) Religion, public health, and a church for the 21st century. International Review Mission 95(376/377): 59–72.

- African Religious Health Assets Programme (2006) Appreciating Assets: The Contribution of Religion to Universal Access in Africa. Report for the World Health Organization. Cape Town: ARHAP.

- Barnes LL and Sered SS (eds.) (2005) Religion and Healing in America. New York: Oxford University.

- Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, and Nahin RL (2004) Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States 2002. Advance Data from Vital and Health Statistics, no. 343. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

- Cochrane JR (2006) Religion, public health, and a church for the 21st century. International Review Mission 95(376/377): 59–72.

- Flannelly KJ, Ellison CG, and Strock AL (2004) Methodologic issues in research on religion and health. Southern Medical Journal 97(12): 1231–1241.

- Sloan RP and Bagiella E (2002) Claims about religious involvement and health outcomes. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 24(1): 14–21.

- Traphagan JW (2005) Multidimensional measurement of religiousness/ spirituality for use in health research in cross-cultural perspective. Research on Aging 27(4): 387–419.

- Weller P (2006) Addressing religious discrimination and Islamophobia: Muslims and liberal democracies. The case of the United Kingdom. Journal of Islamic Studies 17(3): 295–325.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.