This sample Risk Factors Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Introduction

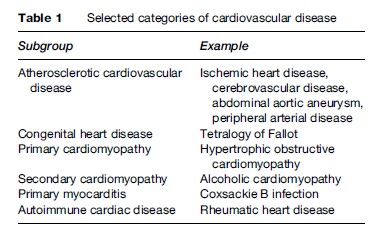

Collectively, cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the leading cause of death of Homo sapiens in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries (World Health Organization, 2002). While they constitute a diverse group of conditions (see Table 1), the subgroup related to atherosclerosis is easily dominant as a cause of death globally, as well as being a leading cause of morbidity throughout at least the developed world. The atherosclerotic group includes (1) ischemic heart disease (IHD), presenting clinically as angina pectoris, acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and acute coronary syndrome (ACS); (2) cerebrovascular disease (CeVD), presenting clinically as transient ischemic attack and stroke; (3) abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA); and (4) peripheral arterial disease (PAD), presenting clinically as intermittent claudication and gangrene. In developed countries, IHD is one of the major causes of heart failure (Braunwald, 1997) and therefore many cases of heart failure in such communities are ultimately due to atherosclerosis. Because atherosclerotic ‘cardiovascular disease’ is so important, in developed countries the phrase cardiovascular disease is understood as referring to the consequences of atherosclerosis unless it is specifically qualified in some other way. That usage will be followed here.

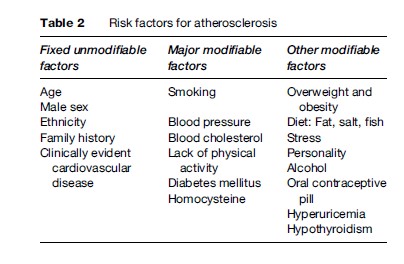

With one notable exception, the absence of a relationship between diabetes mellitus and AAA, the risk factors for atherosclerosis are the same, regardless of the specific anatomical arterial territory affected. That said, it is useful to divide the risk factors for atherosclerosis into three broad groups, according to their implications for prevention (see Table 2). This research paper provides a brief review of the unmodifiable or fixed factors, those not amenable to change, before considering in greater detail the relationships between the major modifiable factors and the risk of CVD, and particularly the evidence that altering the levels of these factors results in a reduction in that risk. The next part of the paper addresses the group of other modifiable factors, several of which are important determinants of one or more of the major modifiable factors, while others have complex epidemiological relationships with cardiovascular risk. The known risk factors for atherosclerosis explain at least 75% of cases of IHD and offer enormous scope for preventive interventions, at both individual and whole-of-population levels (Beaglehole and Magnus, 2002). The paper therefore concludes with a section addressing a possible approach to reducing the burden of cardiovascular disease in a given community, derived from the seminal work of Geoffrey Rose (Rose, 1981). After more than 50 years of intensive scholarly enquiry, more will be gained, and more quickly, by systematically applying what we already know about how atherosclerotic CVD might be prevented than by searching for additional modifiable factors (Beaglehole and Magnus, 2002).

Fixed, Unmodifiable Factors

A large proportion of any individual’s absolute risk of CVD, his or her chance of suffering a significant clinical event related to atherosclerosis in the near future, is determined by a set of factors that he or she cannot change.

Age

The risk of a major cardiovascular event rises with age, in an accelerating fashion. Of the four principal conditions, ACS alone has a notable incidence in the working age group (20–64 years). The median age at which a first-ever stroke is experienced is usually beyond 70 years, and both AAA and PAD are conditions of old age, although the latter may be brought forward by diabetes mellitus.

Male Sex

At any given age, men are at higher risk of CVD than women. The increase in cardiovascular risk with age is smooth in males but accelerates around the time of the menopause in women before slowing once more. In the working age group, the male excess of AMI is three to fourfold (Tunstall-Pedoe, 2003), although this gap narrows considerably in old age. Rates of stroke in males always exceed those in females, but absolute numbers of events are more similar because of the greater longevity of women and the rapid increase in risk with age. AAA is a rare condition in women, by a factor of about seven. The male excess of PAD is at least partly due to historical differences in smoking habits between the sexes.

Ethnicity

The concept of ethnicity combines both biological (including racial) and cultural aspects which differ both within and between populations. The MONICA Project, coordinated by the World Health Organization over a decade from the early 1980s (Tunstall-Pedoe, 2003), confirmed the long-known and obvious international differences in mortality from CVD and demonstrated that they reflected major differences in the incidence of cardiovascular events. However, the project was largely confined to Caucasian populations and had limited representation from both the United States and the UK where there are significant non-Caucasian populations living under relatively good economic conditions. Results from multiracial studies in both these countries show that ethnic differences in modifiable risk factors explain a significant proportion of the ethnic differences in mortality from CVD.

Family History

Family history has long been associated with an individual’s cardiovascular risk. Leaving aside rare conditions such as familial hypercholesterolemia, this relationship almost certainly has some genetic basis, but shared environment and behavior in early life and persistence of some of these habits into adulthood are also likely to be important.

Clinically Evident Cardiovascular Disease

Clinically evident CVD in one major arterial territory is a strong marker of the risk of a major cardiovascular event affecting another. Thus, even among survivors of a stroke, acute coronary events rather than recurrent strokes are the leading cause of death, and men with AAA have a considerably stronger history of AMI than those without aneurysms ( Jamrozik et al., 2000).

Major Modifiable Factors

Although part of an individual’s risk of CVD is determined by factors that cannot be changed, attention to the major modifiable risk factors for CVD can appreciably reduce the risk of experiencing a major cardiovascular event.

Traditionally smoking, blood pressure, and blood lipids have dominated thinking about major modifiable and independent risk factors for CVD, but lack of physical activity has equal standing with members of this trio. Some authorities would also include diabetes mellitus in the set but, while its importance as a determinant of risk is clear, the evidence that this contribution can be reduced, even by the best metabolic control of diabetes, is distinctly limited. Homocysteine, a sulfur-containing amino acid derived principally from meat, has attracted a lot of attention as a further modifiable risk factor.

Of the four major modifiable factors, smoking and physical activity are obviously under the direct control of the individual, while the other two, blood pressure and blood lipids, are related to diet and relative body weight and hence are also largely determined by personal behavior, though less directly. The latter factors are more proximal to events at the vascular endothelium where the lesions of atherosclerosis are initiated and propagated. In addition, because blood pressure and blood lipids are amenable to pharmacological intervention, this has made it easier to demonstrate, via randomized controlled trials, that changes in these factors are followed relatively quickly by changes in the incidence of the clinical endpoints related to atherosclerosis. However, the observational epidemiology for all four risk factors indicates clearly that each has a ‘‘continuous and graded relationship’’ (Stamler et al., 1986) with risk of CVD. In turn, this means that dichotomizing the population into hypertensive versus normotensive, for example, potentially results in large numbers of individuals ignoring advice regarding lifestyle and behavior that, if followed, could materially reduce their risk of CVD.

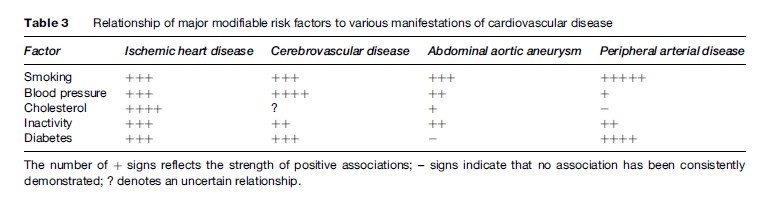

The relative importance of the major modifiable factors differs across the different arterial territories (Table 3) and to some extent across populations. Smoking and diabetes are especially significant in the genesis of PAD, while blood pressure is most closely associated with the risk of stroke. Like the other factors, lack of physical activity has some bearing on risk of major clinical events across each of the arterial territories.

Smoking

There is a strong relationship between smoking and all manifestations of CVD, and the risk rises with both level of consumption and duration of smoking. In the case of IHD, the relative risk for current smokers compared with never smokers is inversely related to age, such that it exceeds tenfold in mid-adulthood and falls progressively into old age. This pattern is consistently apparent but has not been fully explained. Even so, because background risk rises steeply with age, the smaller relative risk experienced by smokers in older age still translates into a sizeable increase in absolute risk and large numbers of additional, and avoidable, events.

Although every reputable medical and scientific organization that has reviewed the evidence agrees that smoking is a major cause of CVD, the biological mechanism underlying the relationship remains uncertain. Carbon monoxide, of which there are large amounts in tobacco smoke, is known to increase the permeability to lipids of the vascular endothelium, and numerous others of the four thousand chemicals in tobacco smoke affect physiological systems that are potentially relevant to the development of atherosclerosis (Leone, 2007). The same mechanisms are likely to explain the significant excess risks of IHD in nonsmokers passively exposed to tobacco smoke.

Importantly, the excess risks of IHD and CeVD associated with current smoking decrease rapidly once an individual gives up the habit, such that the risk returns almost to that of an otherwise equivalent lifelong nonsmoker within a few years (Doll et al., 2004). Curiously, the significant increase in risk of AAA related to smoking appears to persist for several decades after quitting ( Jamrozik et al., 2000), although this question has not been studied anywhere near as extensively. The data on risk of PAD in ex-smokers are inconsistent, with some reports suggesting only a limited reduction of risk, but it is widely accepted that cessation of smoking significantly improves the prognosis once clinical manifestations of PAD, such as intermittent claudication, are apparent.

Blood Pressure

The levels of both systolic and diastolic blood pressure show continuous, graded relationships with cardiovascular risk (MacMahon et al., 1990). The notion of hypertension is therefore a clinical short-cut designed to help doctors identify those at greatest absolute risk of developing CVD. Recognizing this, the World Health Organization and the International Society of Hypertension have progressively lowered the levels of blood pressure used to define the upper limit of clinical acceptability. The fundamental point is clear – the lower one’s blood pressure, the lower the risk of CVD – and messages about determinants of blood pressure levels such as diet (less salt, more fruit and vegetables, maintaining weight in the ideal range) and lifestyle (adequate physical activity, keep any consumption of alcohol within moderate limits) are applicable over virtually the entire population.

Blood Lipids

Like blood pressure, blood cholesterol shows a continuous and graded relationship with cardiovascular risk, and more specifically, coronary risk (Stamler et al., 1986). Thus, apart from the familial condition, the notion of hypercholesterolemia is really a matter of clinical convenience. Serum triglycerides are also related to the risk of both IHD and stroke (Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration, 2004).

Just as there has been debate, from time to time, as to which measure of blood pressure (systolic, diastolic, or pulse pressure) carries most predictive significance, so there has been extensive discussion of which lipid subfraction or the ratios of which subfractions define the risk of major coronary events most precisely. Aside from the fact that an individual’s level of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL cholesterol) is directly related to his or her coronary risk, while that of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL cholesterol) is inversely related to that risk, it has required very large studies to demonstrate statistically significant differences in the prognostic importance of the various lipid subfractions, suggesting that the clinical impact of choosing one from another verges on marginal.

Of greater practical importance are the observations that the level of HDL cholesterol is increased by physical activity and consumption of alcohol at moderate levels, while the level of LDL cholesterol is lower among those who keep their weight in the ideal range and who eat less fat, and especially less saturated fat, which is mainly of animal origin. These data lend themselves to practical advice from health professionals to individual patients and to population-wide health promotion activities. Physical activity and achieving and maintaining weight-for-height in the recommended range are key messages because only 20% of blood cholesterol is exogenous in origin. For most people, higher levels of total and LDL cholesterol represent intrinsic metabolic responses to imprudent choices regarding behavior and lifestyle rather than direct consequences of the amount of fat in their diets.

Where an individual’s level of cholesterol remains a matter of clinical concern, even after he or she has lost weight, begun to exercise more, and reduced the amount of fat consumed, pharmacological treatment can help to reduce the level of cholesterol and the associated coronary risk. This approach is supported by a series of large and well-conducted randomized controlled trials.

Interestingly, the same trials that demonstrated the beneficial effects of statins on coronary risk also consistently showed a reduction in stroke events among those participants taking one of these drugs as compared with a placebo (Baigent et al., 2005). Thus, there is Level I evidence implicating high blood cholesterol as an important risk factor for stroke, a relationship that observational epidemiology has been slow to reveal. It is now evident that a high level of cholesterol is associated with an increased risk of occlusive stroke but a decreased risk of primary intracerebral hemorrhage, relationships that will have been obscured when all types of stroke are considered together. As noted in Table 3, the level of blood cholesterol is only weakly linked to the risk of AAA and has not consistently been linked to the risk of PAD.

Lack Of Physical Activity

In an early and now classic study, Jerry Morris demonstrated that conductors on double-decker buses in London had lower rates of coronary events than did the drivers of the buses, a finding that could not be attributed to preexisting vascular disease. Despite the possibility that physical activity was a potential explanation for this difference, lack of physical activity has been the least investigated of the major, independent, modifiable risk factors for CVD. To be fair, collecting data on frequency, intensity, and duration of physical activity at home, work, and during leisure time is far more difficult than asking about smoking habits or measuring blood pressure or blood cholesterol.

Studies of physical activity in other occupational groups and leisure time physical activity demonstrated reduced coronary risk in those who undertook physical activity regularly, leading to a landmark report from the Surgeon General of the United States, published in 1996 (National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 1996).

Recommendations regarding physical activity have evolved over time as the evidence has accrued. For many years, people were encouraged to undertake periods of vigorous activity lasting 20 min each at least three times weekly. This advice was based on studies of competitive athletes and reflected a pattern of exertion necessary to cause a progressive increase in maximal uptake of oxygen, indicating gains in cardiorespiratory fitness. Blair’s group at the Cooper Institute in Texas was among the first to demonstrate beneficial effects on cardiovascular health – lower risks of both IHD and stroke – as well as general health associated with more moderate levels of regular physical activity (Blair et al., 2001). Their work has been particularly influential in reformulating advice about physical activity such that current recommendations are for at least 30 minutes of moderate physical activity, in bursts of at least 10 minutes each, on most days of the week. For individuals who choose walking as part of their response to this advice, the appropriate level of exertion is usually defined as walking at a pace where the degree of breathlessness is just sufficient to make it difficult to hold a normal conversation.

In terms of benefits to cardiovascular and general health, more is better appears to hold across a wide range of levels of physical activity, although the dose–response relationship eventually tends to a plateau. Paffenbarger’s studies of Harvard alumni demonstrate clearly that one cannot bank the benefits of physical activity undertaken early in adult life; initially active individuals who then become inactive show higher cardiovascular risk than those who remain persistently active, while the opposite transition, from inactive to active, is clearly associated with reductions in risk compared with that experienced by otherwise similar individuals who remain sedentary (Paffenbarger et al., 1984).

Diabetes Mellitus

Diabetes is an important risk factor for occlusive cardiovascular disease, even if not for AAA. To the extent that most cases of diabetes are of adult-onset type, and that this proportion is only likely to increase with the epidemic of overweight and obesity now occurring in many parts of the world, much of the burden of CVD associated with diabetes is theoretically avoidable through prevention of type 2 diabetes. However, as the UK Prospective Diabetes Study has demonstrated, once diabetes has developed, even tight metabolic control of hyperglycemia does not reduce the incidence of large-vessel cardiovascular disease, that is, of events related to occlusion of the coronary, major cerebral, and lower limb arteries (UK Prospective Diabetes Study, 1998). Thus, diabetes once developed may not be a modifiable risk factor for major cardiovascular events.

Homocysteine

That individuals with the rare metabolic defect known as familial hyperhomocystinemia show a vastly elevated incidence of CVD has sparked considerable interest in whether homocysteine plays any role in the genesis of atherosclerosis. Indeed, by the mid-1990s there was already a large body of observational epidemiology implicating homocysteine as a significant independent risk factor for CVD affecting each of the coronary, cerebral, and peripheral arterial territories (Boushey et al., 1995). Like the relationships of CVD with each of smoking, blood pressure, blood cholesterol, and physical activity, this relationship appears continuous and graded, with no threshold level of homocysteine below which there was no association evident. Homocysteine is toxic to vascular endothelium and therefore may be responsible for the initial disruption of endothelial physiology that sets in train the complex series of events leading to atherosclerosis.

Part of the attraction of homocysteine as a significant risk factor for CVD lies in the ease with which levels can be lowered safely and effectively by treatment with folic acid and B vitamins. Ongoing trials may help to provide a definitive answer regarding the utility of treatment with B vitamins for reducing risk of CVD.

Other Modifiable Factors

Numerous other characteristics of individuals have been associated with an increased risk of CVD. From one perspective, once the fixed and major modifiable risk factors are taken into account, the contributions of many of these factors are rather modest. From another perspective, many of these factors cause increases in risk due to changes in modifiable risk factors; for example, diet affects overweight and obesity, which in turn affect blood pressure. Thus from a population perspective these upstream factors may provide the best opportunities for prevention.

Overweight And Obesity

Overweight and obesity have only limited independent contributions to cardiovascular risk, probably because their principal effects relate to their contributions to higher levels of blood pressure and blood lipids. Thus clinical intervention on the two biomedical factors should always include efforts to achieve and maintain a body mass index in the range of 20–25 kilograms per meter (of height) squared. In practical terms, this translates roughly into maintaining a body weight below height in centimeters minus 100. Debate continues as to whether ranges of recommended weight for height should be modified for non-European, and especially Asian, populations (Misra et al., 2005). From a population perspective, the growing epidemic of excess body weight can be expected to increase risk of CVD, and controlling this epidemic is a major public health goal in many countries.

Diet: Salt, Fat, Fish, Fruit, and Vegetables

Dietary salt and fat are also direct upstream factors for raised blood pressure and blood lipids, and, like overweight and obesity, offer obvious targets for intervention. In this regard, it is often not appreciated that meat that appears lean to the naked eye still contains a large amount of saturated fat and that many residents of the developed world would experience only benefits and no adverse effects on their health were they to consume less meat.

Vegetarians have lower blood pressure and lower rates of CVD than omnivores, but which aspect or aspects of the vegetarian diet confers these benefits has proved difficult to identify. In part, a higher intake of fruit and vegetables results in beneficial increases in the potassium: sodium ratio in the diet, with consequent reductions in blood pressure, but vegetarians also consume more fiber and frequently follow a more prudent lifestyle.

The observation that Inuit people experienced far less CVD than one might expect among people whose traditional diet contained so much fat and so little fruit and vegetables eventually led to the identification of the significance of long-chain poly-unsaturated fatty acids for vascular health. These omega-3 compounds have a variety of effects on the vascular endothelium and platelets (as well as other physiological systems) and are now widely available over the counter as dietary supplements. Of greater practical import, however, is the significant body of evidence suggesting that a greater intake of fish would bring benefits to cardiovascular health (Schmidt et al., 2005).

Stress

In this discussion, a distinction is drawn between stress, meaning events and factors external to the individual that may cause some distress, and personality, meaning the intrinsic characteristics of the individual that may shape his or her response to such stimuli. People can often cite anecdotes that suggest that an acute emotional or physical stress has precipitated a heart attack or stroke. The more formal scientific literature does demonstrate a relationship between cumulative exposure to life events that independent observers agree are potentially stressful and significant illnesses of many kinds, but the association of major cardiovascular events with single specific instances such as news of a sudden, unexpected bereavement, is much less clear (Hemingway and Marmot, 1999).

Depression is associated with CVD but the direction of causation is not well understood and so the implications for prevention or treatment of CVD are unclear (Bunker et al., 2003).

There has also been extensive research into the relationship between occupational position and CVD, in part stimulated by the well-established social gradient at least of IHD. The Whitehall studies of British civil servants have been the leading investigations in the field. They suggest that limited latitude to control the pace and pattern of one’s work is associated with greater coronary risk (Hemingway and Marmot, 1999). However, it is difficult to assess if such studies have fully accounted for confounding by more proximal risk factors. Additionally, a response to these findings probably lies more in the realm of organizational management than clinical medicine or public health.

Personality

The time-urgent, competitive, easily angered type A personality enjoyed a long vogue as a potential marker of cardiovascular risk, especially while white collar occupational groups continued to experience a high rate of coronary events. That epidemiological picture has since undergone a radical change, with people of lower socioeconomic position now being at greater risk of CVD in many developed countries. The focus on personality as a cardiovascular risk factor has also faded because of the difficulties in classifying individuals’ personalities reliably. There is also only limited evidence that personalities can be changed, although new ways of responding to the stresses of everyday life can be learned, and the evidence that attempting to do so results in a meaningful reduction in cardiovascular events is scant indeed.

Alcohol

Consumption of alcohol shows a J-shaped relationship with cardiovascular risk, such that lowest rates of events are observed among individuals who regularly consume one to two alcoholic drinks (10–20 g of alcohol) daily. There are somewhat higher risks in complete abstainers, and progressively increasing risks in those who consume alcohol at higher levels than those mentioned (McEdluff and Dobson, 1997), whether on a regular basis or as binges. Drinking alcohol raises levels of HDL cholesterol and both acute and regular heavy intake are associated with higher levels of blood pressure.

Oral Contraceptive Pill And Hormone Replacement Therapy

Because estrogens are prothrombotic, there are theoretical reasons for predicting that women taking exogenous estrogens in the form either of oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) or hormone replacement therapy (HRT) would have an increased risk of occlusive cardiovascular events. This prediction was certainly fulfilled for first-generation OCPs, which had relatively high levels of estrogen. It is likely that modern, lower-dose contraceptive pills carry a smaller relative risk, and the absolute risk of an acute coronary event or stroke in a woman taking OCPs has always been small, because the background risk of such events in women of reproductive age is very small indeed.

HRT stands to mitigate many of the metabolic changes consequent on menopause that are likely to increase cardiovascular risk. Formal proof of the hypothesis that HRT would also reduce the incidence of major cardiovascular events is still awaited, because one large trial testing this prediction was suspended prematurely once it became clear that women taking HRT also had a significant increase in the risk of thromboembolic cardiovascular events and of developing breast cancer (Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators, 2002). Subsequent reports have tended to confirm that HRT increases risk of CVD (Vickers et al., 2007).

Socioeconomic Position

While the incidence of IHD originally showed a positive relationship with socioeconomic position, that association has now been reversed so that the least well-off have the highest rates of CVD in Western developed countries, although this transition is occurring later in developing countries. Important variations in the social distributions of many of the other behavioral risk factors for CVD almost certainly contribute to this picture and, given the available evidence, strategies to modify those factors are likely to reduce social gradients in cardiovascular health much faster than interventions to reduce disparities in economic circumstances.

Other Risk Factors

There is a considerable literature on hyperuricemia as a marker of cardiovascular risk, and it is well recognized that hypothyroidism is associated with an increased risk of CVD. There is also reasonable evidence for other putative risk factors (Marmot and Elliott, 2005).

Multiple Risk Factors

From a population perspective, there is ample evidence that the combined effects of multiple risk factors contribute to differences in rates of CVD between countries and changes in risk factor levels are related to changes in rates of CVD events (Tunstall-Pedoe, 2003).

While the statistical relationships between risk factors and the experience of CVD are complex, patients, clinicians and public health authorities can find these matters easier to discuss in terms of summary numbers for relative risk. As a great oversimplification, each of smoking, hypertension, and inadequate physical activity doubles an individual’s risk of a major cardiovascular event, and hypercholesterolemia and diabetes increase risk by up to three times, each of these comparisons being with individuals who do not have the relevant risk factor. Where more than one risk factor is present, the effects multiply, such that an inactive smoker with high blood pressure has approximately eight times the risk of experiencing a major cardiovascular event compared with a physically active, normotensive nonsmoker.

While this approach facilitates discussion between patients and their clinicians, it ignores the graded relationships between each of the major modifiable factors and cardiovascular risk and also omits the individual’s fixed factors from the consideration. Thus, there has been a concerted move in recent years to encourage a more all-encompassing assessment of individual patients and population groups, the results of which are usually expressed in terms of absolute cardiovascular risk. This is the probability that a given individual will experience a major cardiovascular event in the next decade, given his or her sex and age and existing levels of each of at least smoking, blood pressure, and blood total cholesterol (Smith et al., 2004). Relative risk, comparing smokers with non-smokers, for example, can be somewhat misleading; the numerical multiplier might be large, but if it is applied to a low background risk such as the incidence of CVD in women in the reproductive age group, the resulting absolute risk is still modest. By contrast, as well as being more comprehensive, the approach based on absolute risk fosters concentration of intervention efforts on those likely to gain most (Smith et al., 2004).

The presence of multiple risk factors also comes into play in the concept of the metabolic syndrome. This refers to a clustering of abdominal obesity, high blood pressure, abnormalities of lipid profiles, and insulin resistance, but this is an evolving area, with multiple definitions of the syndrome available. Apart from identifying a possibly sizeable subgroup of the population at particularly high risk of CVD, it is not yet clear what advantages the label of metabolic syndrome offers for clinical management of cardiovascular risk over and above attention to each of the principal elements of the cluster of risk factors.

Practical Steps For Prevention Of Cardiovascular Disease

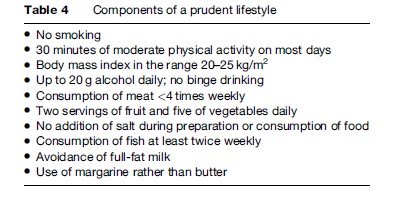

It has now been over 25 years since Geoffrey Rose first identified the inherent limitations in the high-risk strategy, used alone, for improving the health of the population and suggested that mass strategies aimed at whole communities had potentially greater impact (Rose, 1981). The goal for public health is therefore to achieve population-level reductions in the major modifiable risk factors by shifting the risk factor distribution to the left through primary prevention (the population approach) as well as secondary prevention in individuals at elevated risk. Much can be achieved through population-level interventions, such as tobacco control using education, legislation, and taxation. Nevertheless, the development and implementation of effective mass strategies for the prevention of CVD (and noncommunicable diseases more generally), and specifically strategies that address multiple risk factors, remains a challenging problem. Table 4 lists ten behaviors for which there is a varying degree of epidemiological evidence of an association with lower rates of morbidity and mortality, principally from CVD and common cancers. For some of these, such as not being a smoker, there is ample evidence that the imprudent counterpart has a causal association with ill-health. For others, such as type of milk consumed, the significance may lie in indicating acceptance or nonacceptance of a broader message about reducing consumption of saturated fat. Importantly, no involvement of a health professional is required to assess these behaviors and many are potentially amenable to mass interventions. These behaviors are within the grasp of most individuals with adequate resources and supportive environments. In addition, once adopted, many can become permanent, even automatic parts of an individual’s lifestyle. They become habits that are truly healthy and for which only very modest ongoing mental effort is required for their maintenance. For example, it is not a matter of permanently being on a diet, but one of having adopted a pattern of eating and drinking that is enjoyable but also consistent with best available medical knowledge and not conducive to gaining weight.

Several of the behaviors in Table 4 are determinants of medically defined risk factors such as hypertension or hypercholesterolemia. A focus on the prudent lifestyle therefore addresses primary prevention and obviates the need for screening that is inherent in the high-risk approach (Rose, 1981). This distinction is in keeping with Rose’s description of mass strategies as being radical, in the sense of preventing the development of risk, while high-risk strategies are palliative, because they address risk that has become established (Rose, 1981).

While the components of a prudent lifestyle may be largely amenable to individual choice, many are also strongly affected by cultural norms (such as the Mediterranean diet), legislative controls (for example, on smoking), and environmental factors (for example, promoting opportunities for physical activity).

Prevalence Of A Prudent Lifestyle

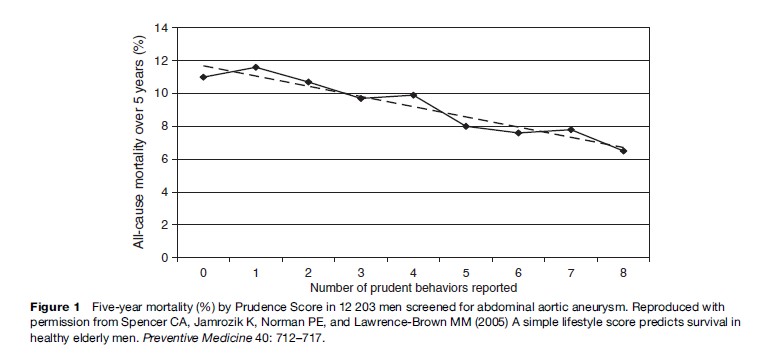

As part of the baseline assessment undertaken in the course of a population-based trial of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), Spencer et al. ascertained the adherence of 12 203 men aged 65–83 years to eight of the behaviors listed in Table 4 (Spencer et al., 2005). The resulting lifestyle scores, calculated as the simple sum of eight dichotomous answers, showed a bell-shaped distribution, indicating that the majority of these individuals already exhibited some health consciousness. By the same token, however, the majority also has scope to adopt additional elements of the prudent lifestyle. Combining these two interpretations suggests that most individuals have a base of health-related self-efficacy upon which they could draw when attempting to make changes to their lifestyle.

Prospective follow-up over 5 years of these men showed that, among those with no history of major cardiovascular events or angina, cumulative all-cause mortality decreased in an almost linear fashion from 12% among those with a lifestyle score of 0 to 6% among those with the maximum prudence score of 8 (see Figure 1) (Spencer et al., 2005). When the data were divided at the median lifestyle score of 4, the lower half had a hazard ratio for all-cause mortality of 1.3 (95% CI, 1.1–1.5) relative to the upper half. The findings in men with clinically evident vascular disease were similar. Thus the Prudence Score is not only simple to calculate, it also has considerable prognostic significance.

Conclusion

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death of humans. Our knowledge of factors contributing to the risk of CVD is both extensive and very detailed. We now understand that, for many of the important causal factors, risk rises progressively with the degree of exposure rather than exhibiting some sort of threshold. Thus, while easy to apply, clinical dichotomies between ‘normal’ and ‘at risk’ are simplistic and misleading. Further, there is abundant evidence from both observational studies and randomized trials that reducing levels of major modifiable factors is quickly followed by decreases in the incidence of major cardiovascular events. It follows that advice regarding prudent lifestyle and behavior in relation to risk of CVD is almost universally relevant and should not be delivered only to a selected subgroup of the population bearing a particularly adverse profile of risk factors. The pressing challenge is to broaden the understanding and application of this principle among both health professionals and policy makers; it is to apply better what we already know to control CVD in population, not to search for new risk factors.

We have left undone those things which we ought to have done; and we have done those things which we ought not to have done; and there is no health in us. (Church of England, 1992)

Bibliography:

- Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration (Writing Committee: Patel A, Barzi F, Jamrozik K, Lam TH, Lawes C, Ueshima H, Whitlock G, Woodward M) (2004) Serum triglycerides as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease in the Asia Pacific region. Circulation 110: 2678–2686.

- Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, et al. (2005) Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: Prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet 366: 1267–1278.

- Beaglehole R and Magnus P (2002) The search for new risk factors for coronary heart disease: Occupational therapy for epidemiologists? International Journal of Epidemiology 31: 1117–1122.

- Blair SN, Cheng Y, and Holder JS (2001) Is physical activity or physical fitness more important in defining health benefits? Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 33(supplement 6): S379–S399.

- Boushey CJ, Beresford SA, Omenn GS, and Motulsky AG (1995) A quantitative assessment of plasma homocysteine as a risk factor for vascular disease. Probable benefits of increasing folic acid intakes. Journal of the American Medical Association 274: 1049–1057.

- Braunwald E (1997) Cardiovascular medicine at the turn of the millennium: Triumphs, concerns and opportunities. New England Journal of Medicine 337: 1360–1369.

- Bunker SJ, Colquhoun DM, Esler MD, et al. (2003) ‘‘Stress’’ and coronary heart disease: Psychosocial risk factors. Medical Journal of Australia 178: 272–276.

- Church of England (1992) Book of Common Prayer.

- Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, and Sutherland I (2004) Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. British Medical Journal 328: 1519.

- Hemingway H and Marmot M (1999) Evidence-based cardiology: Psychosocial factors in the aetiology and prognosis of coronary heart disease. Systematic review of prospective cohort studies. British Medical Journal 318: 1460–1467.

- Jamrozik K, Norman P, Spencer CA, et al. (2000) Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: Lessons from a population-based study. Medical Journal of Australia 173: 345–350.

- Leone A (2007) Smoking, haemostatic factors, and cardiovascular risk. Current Pharmaceutical Design 13: 1661–1667.

- MacMahon S, Peto R, Cutler J, et al. (1990) Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 1. Prolonged differences in blood pressure: Prospective observational studies corrected for the regression dilution bias. Lancet 335: 765–774.

- Marmot M and Elliott P (eds.) (2005) Coronary Heart Disease Epidemiology: From Aetiology to Public Health, 2nd edn. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- McElduff P and Dobson AJ (1997) How much alcohol and how often? Population-based case-control study of alcohol consumption and risk of a major coronary event. British Medical Journal 314: 1159–1164.

- Misra A, Wasir JS, and Vikram NK (2005) Waist circumference criteria for the diagnosis of abdominal obesity are not applicable uniformly to all populations and ethnic groups. Nutrition 21: 969–976.

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (1996) Physical activity and health: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Paffenbarger RS, Hyde RT, Wing AL, and Steinmetz CH (1984) A natural history of athleticism and cardiovascular health. Journal of the American Medical Association 252: 491–495.

- Rose G (1981) Strategy of prevention: Lessons from cardiovascular disease. British Medical Journal 282: 1847–1851.

- Schmidt FB, Arnesen H, Christensen JH, Rasmussen LH, Kristensen SD, and De Caterina R (2005) Marine n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and coronary heart disease: Part II. Clinical trials and recommendations. Thrombosis Research 115: 257–262.

- Smith SC, Jackson R, Pearson TA, et al. (2004) Principles for national and regional guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention: A scientific statement from the World Heart and Stroke Forum. Circulation 109: 3112–3121.

- Spencer CA, Jamrozik K, Norman PE, and Lawrence-Brown MM (2005) A simple lifestyle score predicts survival in healthy elderly men. Preventive Medicine 40: 712–717.

- Stamler J, Wentworth D, and Neaton JD (1986) Is relationship between serum cholesterol and risk of premature death from coronary heart disease continuous and graded? Findings in 356,222 primary screenees of the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT). Journal of the American Medical Association 256: 2823–2828.

- Tunstall-Pedoe H (ed.) (2003) MONICA Monograph and Multimedia Sourcebook. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group (1998) Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet 352: 837–853.

- Vickers MR, MacLennan AH, Lawton B, et al. (2007) Main morbidities recorded in the women’s international study of long duration oestrogen after menopause (WISDOM): A randomised controlled trial of hormone replacement therapy in postmenopausal women. British Medical Journal 335: 239–252.

- Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators (2002) Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: Principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association 288: 321–333.

- World Health Organization (2002) The World Health Report 2002 – Reducing Risks and Promoting Healthy Life. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.