This sample Stigma of Mental Illness Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Introduction

Stigma is a pervasive social force that has powerful consequences for those who are stigmatized and for society itself. Stigma acts to decrease life opportunities among those that it affects by reducing social contacts, housing options, and employment opportunities. Further, stigma causes affected individuals to underutilize health care in order to avoid becoming stigmatized. As a result, larger society is adversely affected. Society becomes burdened by the costs of those who neglect adequate treatment and whose illness conditions worsen due to fear of stigma. Further, society suffers from the spread of infectious diseases (such as AIDS) that remain untreated due to the threat of stigma. Finally, society is adversely impacted by the loss of productive citizens and a further loss of fundamental human rights by the stigmatized.

Instead of being confined to a strict definition, stigma has been understood primarily through the ideas of several leading theorists. These ideas have ranged from conceptions that focus on individuals to those that examine society to explain how stigma works. The concept of stigma has included internal psychological processes within the person, interpersonal social processes between individuals and groups, and large-scale processes on the level of culture and politics.

Stigma is closely associated with concepts such as discrimination and racism. However, some important distinctions exist. While stigma has traditionally been applied to either behavioral or physical deviance, discrimination has been applied much more generally to social characteristics such as race, gender, and socioeconomic status. Further, while stigma has typically been applied to individual traits, discrimination usually has been applied to group characteristics. Lastly, discrimination has tended to focus responsibility on those doing the discriminating. Stigma, in contrast, has focused more attention on the stigmatized person himor herself. Researchers are currently examining the limits of each concept both theoretically and empirically to determine how these closely related processes complement or contradict one another.

Definitions Of Stigma

Because thinking regarding this concept has changed over time, definitions of stigma have also been adapted as theorists and researchers have modified their views toward what this concept should encompass. As a result, although most definitions of stigma share common features, particular definitions of stigma may emphasize one or more dimensions as central. Further, because stigma has been studied from various disciplinary perspectives (e.g., sociology, psychology, or anthropology), a particular theory may also emphasize the theoretical orientation or the discipline of that particular investigator.

Sociologist Irving Goffman’s book written in 1963, Notes on the Management of a Spoiled Identity, is widely viewed as the first essential social and behavioral science formulation of stigma. Goffman defines stigma as ‘‘an attribute that is deeply discrediting’’ and proposes that the stigmatized person is reduced ‘‘from a whole and usual person to a tainted, discounted one’’ (Goffman, 1963: 3). While Goffman’s definition implies that stigma takes place because of some characteristic that an individual possesses, he also emphasizes the importance of how others interpret the stigma by describing stigma as ‘‘a special kind of relationship between an attribute and a stereotype’’ (Goffman, 1963: 4). Here an attribute could be a physical blemish or functional impairment, or a psychological trait. From Goffman’s perspective, stigma occurs when a person is characterized by society (i.e., the meanings that others attach to the stigmatized attribute) in a way that differs from the characteristics that person actually possesses.

The next definition of stigma, proposed by social psychologists ( Jones et al., 1984), uses the term mark to describe how society identifies a deviant condition that initiates the stigmatizing process. The mark, which is seen as central to who the person is, then discredits the stigmatized person by defining the person as flawed, spoiled, contaminated, or undesirable (e.g., similar to the process of branding a slave in ancient times). This perspective emphasizes how the mark and its associated negative meanings engulf how the person is seen by other members of society and accordingly emphasizes stigma as being located within the person who is stigmatized.

Similarly, a definition of stigma proposed by another group of social psychologists (Crocker et al., 1998) defines stigma as taking place when an objective characteristic of the individual leads to a negatively valued social identity. For example, someone who walks with a limp may be discredited by the term cripple. However, this perspective also emphasizes that the negative attribute is interpreted within the social context of the stigmatized individual. These authors thus incorporate the social context in defining whether and how a stigmatized attribute devalues an individual. That is to say, a person with epilepsy may be discredited by having uncontrollable seizures that powerfully alter behavior or because within a certain cultural context, the seizures are attributable to supernatural factors.

A separate psychological perspective approaches stigma from the viewpoint of evolutionary psychology (Kurzban and Leary, 2001). Evolutionary psychology is based on the principle of natural selection, which is defined as a process by which the organisms best adapted to their environment tend to survive and transmit their genetic characteristics to succeeding generations. According to this view, natural selection favors the survival of those species who adapt to or overcome obstacles posed to them over time by evolution. To aid in this adaptation, distinct information-processing structures exist within the mind to solve specific problems encountered in the social domain. These cognitive structures motivate the individual to avoid interactions with certain categories of people that would lessen that individual’s likelihood of eventual survival. The first category resulting from these cognitive structures is that of a poor social exchange partner: individuals are avoided who may cheat in a social exchange and who provide little in terms of social benefit. The second category is that of out group exploitation: Individuals are excluded from gaining the benefits of group membership and instead are targeted for exploitation as an inferior group. The third category consists of parasite avoidance: Individuals who are viewed as likely to carry contagious diseases are avoided. Stigma results from the categorization of people into these groups by adaptive cognitive mechanisms: By classifying people into such categories, the stigmatizing individual thus increases his or her probability of survival.

In addition to the aforementioned conceptualizations, one sociological framework has focused on how a combination of societal forces result in stigmatized individuals being excluded from everyday life (Link and Phelan, 2001). Rather than emphasizing one or two primary components to define stigma, Link and Phelan view stigma as a broader concept that connects together six interrelated components. The first component, labeling, consists of when people distinguish a human difference as important and give it a label. An example might be after an individual hears voices and talks to himor herself, he or she is then labeled as having mental illness. The second component, stereotyping, takes place when beliefs of a cultural group connect labeled individuals to negative characteristics. For example, people with mental illness might be seen as being very dangerous. The third component, cognitive separation, takes place when labeled persons are seen as so different from normal people that a complete separation of us (normals) from them (deviants) is achieved. The fourth component, emotional reactions, includes the emotional responses to stigma felt by both stigmatizers (e.g., fear) and the people who are stigmatized (e.g., shame). The fifth component, status loss and discrimination, results when labeled individuals feel themselves to be less valued than other members of society and are treated unfairly (i.e., discriminated against) by others. Link and Phelan describe discrimination as primarily occurring either when one person treats another person unfairly or when practices of larger institutions or laws disadvantage stigmatized groups. Lastly is the idea that the entire stigma process depends on one group possessing the power (either social, economic, or political) to actually make these stigma components harmful to those who are stigmatized. That is, the group who stigmatizes must be higher in status than the group who is stigmatized in order for the negative effects of stigma to occur.

From these multiple definitions, we can thus trace how stigma has evolved from a conceptualization involving a stigmatizing attribute and cognitive stereotyping processes to a more complex formulation incorporating evolutionary forces, social factors, and political processes. The manifold domains of stigma continue to be refined as researchers further identify the empirical processes by which stigma works.

Categorical Versus Dimensional Definitions Of Stigma

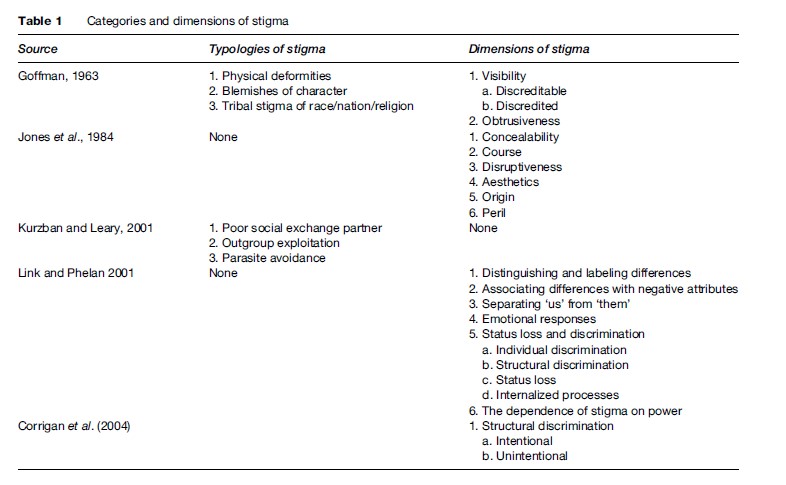

As definitions of stigma have incorporated a wider array of processes, there has been a shift in defining stigma according to dimensions as opposed to categories (or typologies; see Table 1). Two stigma frameworks emphasize categories of stigma, or classifications of the different manifestations that stigma may take (Goffman, 1963; Kurzban and Leary, 2001). Like the evolutionary framework described earlier, Goffman (1963) separates stigma into three types. The first type, physical deformities, indicates abominations of the body. The second, blemishes of character, includes characteristics (e.g., having served a jail sentence) that impugn the person’s moral integrity. The last category, tribal stigma of race, nation, and religion, encompasses stigmas that can be inherited and equally affect all family members. Using this classification, a particular stigma (e.g., attached to being an alcoholic) could be categorized as belonging to one of these three types (e.g., a blemish of character).

Later definitions emphasize dimensions of stigma – attributes or components of stigma that could apply singly or in combination in a matter of degree to any given stigma. The stigma framework proposed by Jones et al. (1984) is particularly known for its proposed six dimensions of stigma. The first dimension, conceal ability, indicates how detectable the stigmatized characteristic is to others. The second, course, describes whether the stigmatizing condition is reversible over time. The third dimension, disruptiveness, indicates the extent to which a stigmatizing trait strains interpersonal interactions. The dimension of aesthetics reflects concerns about the extent to which a stigmatizing characteristic elicits an instinctive reaction of disgust. The fifth, origin, refers to how the condition came into being, with an emphasis on how perceived responsibility for the condition greatly influences others’ reactions. The last dimension, peril, refers to feelings of danger that the stigmatized trait induces in others. Other theories of stigma that identify dimensional aspects similarly organize stigma into characteristics that vary in degree rather than assigning them into fixed categories. For example, utilizing Link and Phelan’s (2001) dimensional definition, a person encountering a stigmatizing event (e.g., being hospitalized in a psychiatric unit) may undergo labeling more or less strongly, may encounter negative stereotyping and separation of us from them that is more or less complete, etc. A stigma may vary on these dimensions in accordance with the nature of the stigma, the individual’s particular circumstance, and the sociocultural context. Although stigma dimensions can hypothetically function independently, in reality they are often intertwined and exert influence upon one another. For example, utilizing Jones et al.’s framework, stigmas that are genetic in nature (origin) may tend to be relatively inflexible to future change (course).

How a stigma varies on different dimensions can be seen to give rise to the stigma classification systems. For example, Goffman’s typologies of physical deformities and blemishes of character are likely to differ in concealability (a stigma dimension). These differences in concealability (i.e., blemishes of character tend to be concealable while physical deformities are not) may in great part determine why these two types of stigmas are viewed as categorically different. One advantage to definitions of stigma that emphasize its dimensional aspects is that they provide a more nuanced view of what the salient aspects of stigma consist of. Further, considering the dimensions of stigma provides a set of attributes that may illustrate how that stigma affects the individual.

Models Of How Stigma Is Experienced By The Individual

We next describe the most prominent models of how stigma is seen to affect the individual. Reviewing such models is essential to conceptualizing how stigma works. Like the definitions of stigma, models of how stigma exerts its negative effects on individuals have developed from processes that primarily focus on individuals to models that incorporate the larger social and political context. Further, although many of these models focus on mental illness stigma specifically, they can be used to illustrate how the stigma process works more generally.

Goffman’s Model Of Stigma

Goffman (1963) describes stigma as a process where the person is socialized into a new stigmatized identity. This process begins with a stigmatized person learning society’s view of the stigma and what it might be like to have a particular stigma. The person then adopts a stigmatized role by gradually identifying with the stigmatized status. For example, a person with mental illness (whose stigma is viewed as not being visible) thus passes from a normal status when diagnosed with mental illness to the status of a person who is potentially discreditable (if others find out about the illness). If others discover the person’s condition, he or she will pass onto a discredited status. In this view, stigma occurs as the person assumes a new identity that is socially constructed.

Social Psychological Models Of Stigma

Following Goffman, Jones et al. (1984) utilize a social psychological perspective to examine the role of the individual in response to stigma. Jones et al. conceptualize stigma as mainly working through cognitive processes of assigning individuals into categories. Stigma takes place when the mark (the stigmatizing attribute) links the identified person to undesirable characteristics (i.e., stereotypes). The negative meanings conveyed by these stereotypes then lead to discrediting of the stigmatized individual. Disruption in the community member’s emotions, cognitions, and behaviors then occurs when interacting with the stigmatized person.

From another social psychological perspective, Crocker et al. (1998) expanded stigma to include how people maintain their self-esteem through cognitive coping strategies. They also incorporate how social identities are constructed through cognitive processes and how the social context is instrumental in shaping one’s identity. A key addition of this formulation is that both stigmatizers and the stigmatized individual may internalize a negative stereotype that in turn has harmful effects. For example, among stigmatizers, negative stereotyping of stigmatized groups occurs automatically and often outside of the stigmatizer’s awareness. An example of internalized stigma that occurs among stigmatized individuals is that of stereotype threat. Individuals labeled with stigma encounter situations when specific negative stereotypes about a group are known by the stigmatized individual. The threat provided by this stereotype to a person’s self-esteem then negatively impacts the individual’s performance in that situation. For example, a female student who is asked to take a math test (and is aware of the stereotype that females tend to perform more poorly than males on tests of arithmetic ability) will tend to perform worse on the test than a male student due to this threat to self-esteem.

At the heart of Crocker et al.’s formulation is that stigma threatens the stigmatized individual’s self-worth. Stigmatized individuals then select among several possible cognitive coping strategies to avoid threats to self-esteem. For example, the female student in the above situation may psychologically disengage her self-esteem from her ability to do math. Stigma thus may impact the individual by working through psychological well-being (including life satisfaction, self-esteem, and depression) and school achievement.

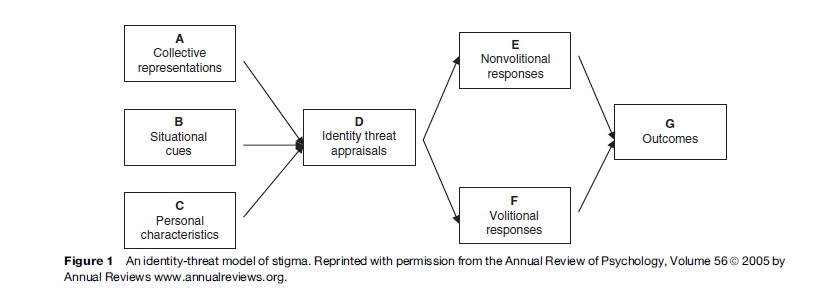

From another social psychological perspective, Major and O’Brien (2005; Figure 1) organize stigma within an identity threat model that integrates how people assess and cope with stigma-related stress. When an individual possesses a devalued social identity, he or she encounters situations that threaten one’s identity. In such situations, the individual first appraises environmental threats to his or her well-being. Appraisal is influenced by three factors: (1) immediate situational cues (how much a situation conveys the risk of being devalued); (2) collective representations (knowledge of cultural stereotypes that shape a situation’s meaning), and (3) personal characteristics of the individual (e.g., how sensitive that individual might be to stigma). Identity threat occurs when an individual appraises the stigma present in the situation as being harmful to one’s social identity and as surpassing one’s ability to cope with this stress. An individual may then respond to this stigma-induced stress in two ways: (1) through an involuntary stress response (e.g., anxiety) and (2) a voluntary coping response. Voluntary coping responses consist of cognitive strategies that reduce threat to the self in reaction to stressful events. For example, a stigmatized individual may attribute a negative outcome (e.g., not getting a job promotion) to discrimination (e.g., racial hiring preferences) rather than to one’s own efforts or abilities at work. Stress due to identity threat then affects individuals through impacts on self-esteem, academic achievement, and health.

Other social psychologists have added emotional and behavioral aspects of stigma to its cognitive aspects. The cognitive, affective, and behavioral components of stigma are represented as stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination. Stereotypes are cognitive representations that describe individuals as having characteristics that are inaccurate or exaggerated. An example might be people with mental illness being seen as unable to care for themselves. Prejudice in turn refers to a negative emotional reaction toward a stigmatized person. For example, a person might feel fearful toward someone who has mental illness. Discrimination then refers to negative behaviors enacted toward a stigmatized person. An example might be an employer not hiring someone with mental illness. These three components are seen as causally related to one another. Endorsement of negative stereotypes may thus lead to prejudice and subsequent discrimination. The perceived controllability of the stigmatized person’s condition is central to this process. For example, if others view the stigma to be controllable, this will greatly influence how they will feel about (e.g., anger) and then behave toward (e.g., seek to punish) the stigmatized person.

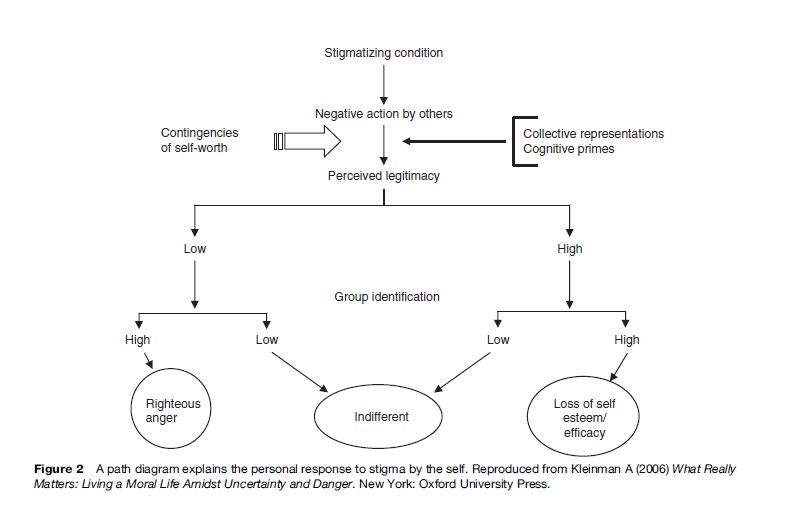

Watson and River (2005) present a model of personal response to mental illness stigma that parallels the stereotyping – prejudice – discrimination model. The first step of self-stigma takes place when stigmatized individuals are aware of the negative images about their group (self-stereotyping). The second step occurs when stigmatized individuals agree with and apply the stereotype to the self. This leads to negative emotional reactions such as low self-esteem (self-prejudice). The final step results in behavioral responses by the individual (such as not pursuing work) which limits life opportunities (self-discrimination).

Watson and River further propose a two-part model to explain the personal response of individuals to stigma (Figure 2). An individual first appraises whether an instance of stigma encountered in a specific situation is legitimate or illegitimate. Appraisal is determined through collective representations (which consist of cultural stereotypes and perceived social statuses), which are activated by cognitive primes (information emerging from the situation). After appraisal occurs, whether an individual highly identifies with the broader stigmatized group will determine personal reactions. For example, an individual who perceives stigma based on nationality as illegitimate and who closely identifies as a person from a particular national group will respond with righteous anger and an increase in self-esteem.

Sociological Models Of Stigma

In comparison, models based on sociological theory have used labeling theory to describe stigma. This concept, based on symbolic interactionism, proposes that the meaning and value of interpersonal actions are socially constructed. That is, the meaning of deviant behavior is continuously interpreted by how that behavior is described by language and symbols. Social responses to behaviors are shaped by shared cultural descriptions of what the behavior means. For example, a person who hears voices and talks aloud to himself is commonly described as someone who has mental illness, and that his behavior is erratic and unpredictable. The potential dangerousness of such a person is symbolized by how psychiatric patients are locked away and secluded during inpatient treatment. How a person comes to view oneself then arises from perceptions of how others view and respond to him or her. When these self-conceptions become fixed, individuals become socialized into a specific role. These roles are accompanied with behaviors that the individual then is expected to fulfill.

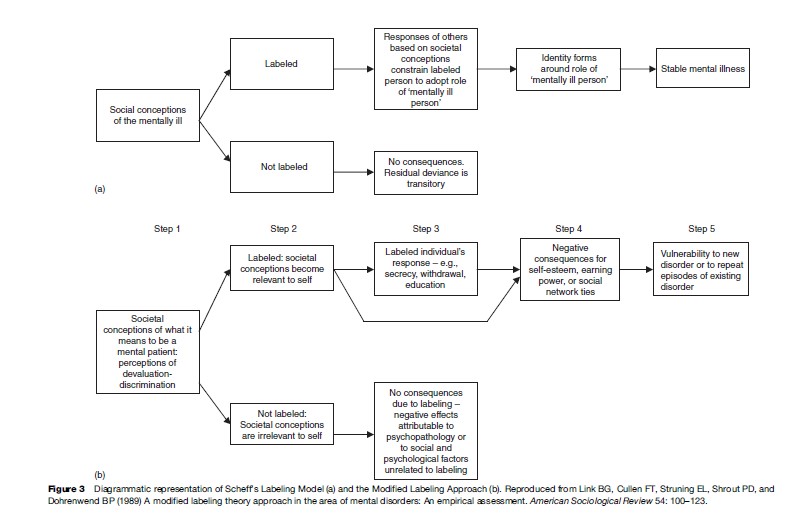

Scheff (1966; Figure 3(a)) proposed a labeling theory where deviant labels lead to changed perceptions and social opportunities for an individual. Mental illness stereotypes (i.e., identifying what is considered crazy) are learned as part of socialization and engaging in everyday life. When deviant behaviors repeatedly violate social rules, this may be perceived by others as a sign of mental illness, or a characteristic of the person. Once labeled as mental illness, a patient role may emerge as a master status that dominates other statuses due to its highly discrediting nature. Responses from others (such as rejection from social networks) then limit the person to the role of someone who is mentally ill and block attempts to return to normal social roles. Individuals labeled with mental illness may further conform to their altered roles, which results in future symptomatic behavior. Scheff proposed that labeling was one of the most important factors in continued psychiatric symptoms.

Link et al. (1989; Figure 3(b)) proposed a Modified Labeling Theory that stated that mental illness labeling and stigma placed people at risk for negative outcomes that may worsen already existing mental disorders. Link et al. proposed that all members of a society internalize notions of what it means to be labeled with mental illness. They emphasized two components of these internalized conceptions. These components consist of the degree that all members of society believe that people with mental illness will be devalued (i.e., lose status) and discriminated against (e.g., be denied life opportunities such as employment). Labeling occurs through contact with treatment. At this point, beliefs about how the community will treat a person with mental illness now become personally relevant. Labeled individuals may then respond to perceived future rejection in one of three ways: (1) secrecy or concealing one’s treatment history, (2) withdrawal or restricting social contact to people who accept one’s condition, and (3) education or changing others’ views to ward off negative attitudes. Negative consequences may result from the individual’s response to stigma. For example, while a response such as withdrawal may protect patients from some harmful aspects of stigma, it may also limit life chances by reducing opportunities for social contact. These negative impacts on self-esteem, social contacts, and employment opportunities are then seen to increase vulnerability to future episodes of mental disorders.

Models Of Stigma That Utilize Perspectives From Society

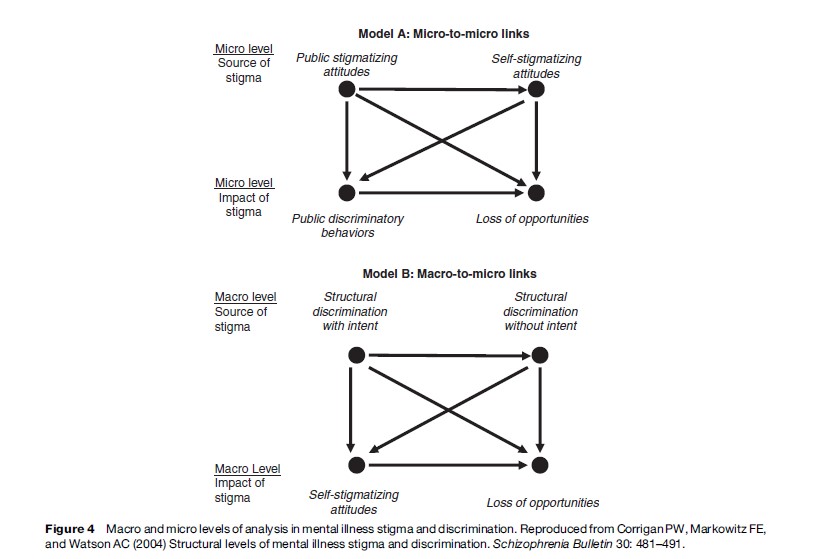

Another model describes mental illness from the perspective of society that includes an analysis of economic, political, and historical factors (Corrigan et al., 2004; Figure 4). Such a framework is important in understanding how stigma may be generated by larger forces in society. Corrigan et al. describe two types of structural discrimination. The first, intentional institutional discrimination, occurs when policies of institutions intentionally restrict the rights of people with mental illness. Here the decision-making group of an institution intentionally implements policies to reduce a particular group’s opportunities. For example, government legislatures may craft laws that restrict people with mental illness from voting. The second type of structural discrimination takes place when policies limit the rights of people with mental illness in unintentional ways. For example, insurance companies within the United States do not insure mental illness at the same level as physical illnesses because they judge that it would be too expensive. This decision is not specifically intended to discriminate against people with mental illness. However, such a decision results in fewer financial resources being devoted to treating people with mental disorders. What is key in both types of structural discrimination is that people with mental illness are negatively affected by discriminatory policies that take place on broader levels of society.

One other perspective, proposed in regards to HIV/ AIDS, identifies stigma in a broader framework of power and as central to reproducing means of social control within a society (Parker and Aggleton, 2003). These authors draw from philosophers and sociologists who propose that forms of social control are embedded in each society’s formalized way of knowing and perceiving the world. Because these means of social control are seen as natural and accepted, the ability of stigmatized individuals and groups to resist marginalization is limited. These authors argue that stigma is utilized by identifiable actors within social groups who use such social control to legitimate their dominant positions in society.

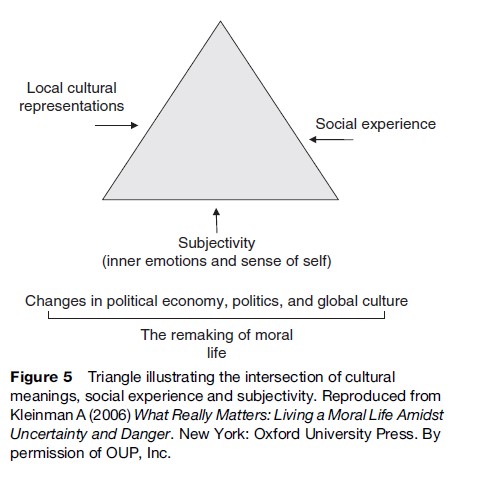

One final anthropological perspective proposes that stigma is embedded in what is most at stake for sufferers and their social world (Yang et al., 2007; Figure 5). What matters most in a local world is determined by the interaction of cultural meanings, social experience, and subjectivity (inner emotions and sense of self ). Thus, people within particular social worlds find certain things to greatly matter, such as status, money, life chances, health, good fortune, a job, or relationships. Stigma is felt most powerfully by people in their social contexts by threatening the life domains that matter most to them. For example, in Chinese cultural groups, the effects of stigma are not limited to the individual but are felt most acutely on the family’s ability to continue the family lineage. Since both the stigmatized and stigmatizers struggle with the daily activities that make social life matter, understanding what is most valued enables us to understand how stigma shapes the behaviors of both groups. This perspective also enables us to identify the family, health and social service providers, and even the stigmatized persons as potential sources of stigma.

Summarizing The Models Of Stigma

In tracing through the above models, we can observe the different mechanisms by which stigma has been seen to affect individuals and groups. Although these models emphasize different components as key to the stigma process (e.g., one highlights the effect of internalized stereotypes, while another emphasizes societal processes), these models can be seen to complement rather than contradict one another. These models also provide valuable perspectives by which to intervene with the negative effects of stigma.

How Stigma Affects Health And Recovery From Illness

Stigma not only negatively impacts a person’s social status, but it also detrimentally affects both psychological and physical health. The above models illustrate possible mechanisms by which stigma causes its negative effects. A great deal of research has also demonstrated the harmful effects of stigma on health and recovery, especially among the stigmatized conditions of mental illness and HIV/AIDS.

Both mental illness and HIV/AIDS have been identified by public attitude surveys across cultures as being among the most stigmatized of conditions. The label of mental illness evokes a great deal of negative and fearful reactions. In public attitude surveys, the label of mental illness is commonly linked to adjectives such as dependent and helpless, on the one hand, and dangerous, different, and unpredictable, on the other. AIDS-related stigma differs from mental illness but also is quite negative. Because the primary routes of transmission for HIV – sexual intercourse and sharing of infected needles – are perceived as voluntary behaviors, people infected with HIV are seen to be responsible for their condition. A great amount of stigma is also attached to HIV/AIDS because: (1) it is perceived as contagious, (2) its course is seen to be unalterable, and (3) the illness is apparent to others in its advanced stages. What the two conditions have in common is that the stereotype of dangerousness appears to underlie much of the public’s willingness to reject these stigmatized individuals.

These negative stereotypes toward people with mental illness and HIV/AIDS have several harmful effects. First of all, stigma acts as a critical barrier to effective treatment for persons with mental illness and HIV/AIDS. Among mental illnesses, stigma causes two negative effects in regards to treatment: (1) many people with mental illness never pursue treatment or (2) others begin but fail to adhere to prescribed treatment. For example, in a representative national study conducted in the U.S., less than 40% of respondents with mental illness in the past year received ongoing treatment (Kessler et al., 2001). Similarly, fears of AIDS stigma may prevent people at risk for HIV from being tested and seeking assistance for reducing risk of contracting the illness. For example, in China over 90% of the estimated 1 million people who are HIV-positive have not yet been tested for HIV because of the intense fear of stigma ( Jing, 2006).

The negative stereotypes associated with mental illness and HIV/AIDS also lead to the devaluation and rejection of people with these conditions. On the individual level, such stigmatized persons face direct discrimination. In one survey of community outpatients with mental illness in the U.S., 42% of respondents reported having been shunned at least sometimes when others learned of their psychiatric treatment (Dickerson et al., 2002). Similarly, people with AIDS have reported suffering from individual discrimination such as being fired from their jobs, evicted from their homes, and denied services. A second form of devaluation occurs through structural discrimination when institutional practices lead to unequal opportunities for stigmatized groups. One prominent example for those with mental illness includes unequal treatment by health insurers toward psychiatric as opposed to physical illnesses. A third form of devaluation takes place through stigmatized individuals themselves, once they have adopted the belief that they will be discriminated against after receiving a stigmatizing label. Once stigma becomes internalized, the patient’s manner of coping with stigma (e.g., through withdrawal or secrecy) can result in negative outcomes.

As a result of these processes, stigma has been linked with many negative outcomes for both people with mental illness and HIV/AIDS. The negative psychological effects of stigma among people with mental illness include low self-esteem, depressive symptoms, and less psychological integration with the community. Other harmful effects include constricted social networks, avoidance of nonfamily members, and noncompliance with treatment programs. Similarly, people with AIDS have been reported to suffer from social isolation, self-blame, increased psychological distress, and self-destructive behaviors. Stigma also limits life opportunities of members of both groups through income loss, increased time of unemployment, and limited access to housing and medical care. The evidence thus overwhelmingly indicates that stigma denies people from both of these stigmatized groups access to important means of recovery. The stigma process also initiates stressors such as rejection and discrimination that make rehabilitation from these chronic illnesses even more difficult to achieve.

Intervening With Stigma: Anti-Stigma Campaigns

Because of stigma’s numerous negative effects, intervening with stigma has become a critically important area of research. Further, stigma interventions benefit society by promoting stigmatized individuals’ opportunities for recovery and enabling them to become productive citizens. The above models of how stigma works have greatly shaped existing interventions to reduce stigma. Because of the prominent place that negative stereotypes have in the formation of stigma, many anti-stigma campaigns have sought to decrease stigma by changing public attitudes toward stigmatized groups.

In recent years, there have been several anti-stigma campaigns as well as public and private research to reduce stigma. The European Federation of Associations of Families of People with Mental Illness’s (EUFAMI) antistigma campaign, Zerostigma, began in October 2005, seeking to replace fear with facts about mental illness. Zerostigma works with various health-care organizations, volunteers, and media across Europe to increase knowledge about stigma for those who suffer from mental illness. One of EUFAMI’s major contributions to antistigma is directing the government’s money to be used more efficiently. Another way EUFAMI helps reduce stigma is by evaluating and promoting new research.

Changing Minds is another anti-stigma campaign funded by the United Kingdom Royal College of Psychiatrists. Launched in 1998, this program targets community members ranging from health-care professionals to the general public. They use print and video media to relay an anti-stigma message to others. Another anti-stigma campaign is taking place in over 20 countries with the World Psychiatric Association’s Open the Doors campaign in 1996. This program specifically targets the stigma associated with schizophrenia. Further, novel interventions have been developed to address the perspectives of specific community groups, including medical professionals, journalists, school children, law enforcement officials, employers and church leaders. Regarding HIV/AIDS, the Ford Foundation funded the HIV/AIDS Anti-Stigma Initiative by involving community-based organizations in the U.S. to increase awareness and to decrease stigma. This campaign also produces research for those who are stigmatized and for the disease itself.

It should be noted, however, that most public education campaigns have occurred in Western countries (such as Germany and the United Kingdom). Also, the positive effects on public conceptions of mental illness due to such programs have been described as modest in impact. Much research has yet to be done to determine what the content of programs should be to most effectively reduce stigma and what form such programs should take to maximize positive attitude change among the general community (Thornicroft, 2006).

The above campaigns and clinical research on stigma intervention have used one of three common approaches: protest, education, and contact.

Protest

By means of protest, a person or a group objects to negative ideas, images, and attitudes about a stigmatized group. Protesting is an active way to reduce offensive and demeaning representations of stigmatized groups in the media. By decreasing stigmatizing images in the media, protesters believe they can reduce stereotypes and stigmatization. For example, a group called Stigma Busters responds to negative media portrayals of people with mental illness in the United States by using actions ranging from letters of concern to protests such as boycotting. While such actions can lessen certain stigmatizing images and behavior, it does not change the public’s stigmatizing attitudes. In fact, protest merely suppresses the targeted negative ideas. Research has shown that when people are forced to suppress negative stereotypes, they become more sensitized to such stereotypes. This in turn may lead to unwanted thoughts about the initial stigmatized group. Additionally, those who suppress stigmatizing ideas and attitudes learn less accurate information about the stigmatized group during educational programs (Corrigan and Penn, 1999).

Education

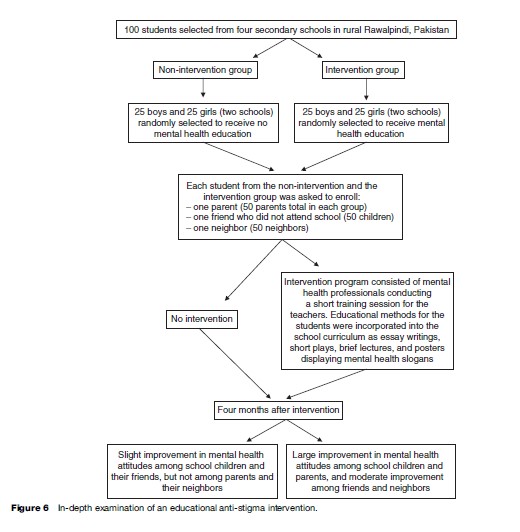

Education seeks to challenge inaccurate ideas with factual information through the media (such as public announcements, lectures, books, and movies). For example, one form of education might be to expose the public to productive works of people with mental illness. Education is not only useful for the general public, but also for those who are stigmatized. Education gives people who are stigmatized alternate strategies to cope with feelings of difference and shame. Education yields positive results in improving conceptions toward people with mental illness. For example, one study demonstrated that after education, participants showed more willingness to believe that people with psychiatric problems benefit from medical treatment and psychotherapy (Corrigan and Penn, 1999). Another study, conducted in rural Pakistan, showed that educating children through a school-based intervention program improved attitudes toward people with mental illness not just among the children but also positively changed the attitudes of the people who they came into contact with (their parents, friends, and neighbors; see Figure 6; Rahman et al., 1998).

The Elimination of Barriers Initiative (EBI), developed by The Center for Mental Health Services, is a large-scale campaign based in the United States that educates the public about inaccurate stereotypes of mental illness. This campaign combats stigma through town meetings, radio, television, and printed announcements, and has reached approximately 150 million people. While EBI is an example of broad-based intervention based on education, it is uncertain whether those who hold stigmatizing views (rather than those who are already aware of and affected by the stigma) were actually exposed to the message and had their views influenced by it.

Contact

The final strategy of contact is accomplished by having personal contact with someone from the stigmatized group. For example, while many people with mental illness work and live among us, they are stigmatized as being unable to work and function normally. Contact gives those who stigmatize an opportunity to engage in a mutual and informal conversation with members of a stigmatized group. These conversations in conjunction with education have led to decreases in stereotyping and stigma among potential stigmatizers. Contact increases acceptance and positive attitudes by exposing community members to people of stigmatized groups who are functioning normally. One study found greater improvements in attitudes after intervention through contact when compared with education alone (Corrigan et al., 2002). It appears that collaborative interaction with a stigmatized person who moderately disconfirms a preexisting stereotype is the most effective form of personal contact.

While each of the three interventions has its specific purpose, these strategies can also be combined. For example, education about a stigmatized group is often combined with the strategies of protest or contact. While contact yields the best results among the three strategies, it is unknown whether stigma is truly decreased or merely suppressed. It is also unclear whether education has an enduring impact on stigma and whether factual information alone is sufficient to bring about change in attitudes. Further, it is not certain whether increasing positive attitudes toward stigmatized persons actually decreases discriminatory behavior toward such individuals. Lastly, stigma’s most harmful effects vary by culture, and stigma intervention should be targeted toward areas that most severely limit a group’s integration into society. In sum, many areas remain unexplored in regards to stigma intervention, and diminishing the impact of stigma may ultimately depend equally upon policy-makers crafting legislation that combats structural discrimination and more easily allows stigmatized persons to integrate into society. Advancing the study of stigma will better enable researchers and other public health experts to identify those areas most in need of government intervention, to reduce the suffering of stigmatized individuals, and to decrease the burden in the societies to which they belong.

Bibliography:

- Corrigan PW, Markowitz FE, and Watson AC (2004) Structural levels of mental illness stigma and discrimination. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30: 481–491.

- Corrigan PW and Penn DL (1999) Lessons from social psychology on discrediting psychiatric stigma. American Psychologist 54(9): 765–776.

- Corrigan PW, River PR, Lundin RK, et al. (2001) Three strategies for changing attributions about severe mental illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin 27(2): 187–195.

- Corrigan PW, Rowan D, Green A, et al. (2002) Challenging two mental illness stigmas: Personal responsibility and dangerousness. Schizophrenia Bulletin 28: 293–310.

- Crocker J, Major B, and Steele C (1998) Social stigma. In: Fiske S, Gilbert D and Lindzey G (eds.) Handbook of Social Psychology, pp. 504–553. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

- Dickenson FB, Sommerville J, Origoni AE, Ringel NB, and Parente F (2002) Experiences of stigma among outpatients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 28: 143–155.

- Goffman E (1963) Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. New York: Prentice Hall.

- Jing J (2006) Fear and stigma: An exploratory study of AIDS patient narrations in China. In: Kaufman J, Kleinman A and Saich T (eds.) AIDS and Social Policy in China. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Jones EE, Farina A, Hastorf AH, et al. (1984) Social Stigma: The Psychology of Marked Relationships. New York: Freeman.

- Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Bruce ML, et al. (2001) The prevalence and correlates of untreated serious mental illness. Health Services Research 36: 987–1007.

- Kleinman A (2006) What Really Matters: Living a Moral Life Amidst Uncertainty and Danger. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Kurzban R and Leary MR (2001) Evolutionary origins of stigmatization: The functions of social exclusion. Psychological Bulletin 127(2): 187–208.

- Link BG, Cullen FT, Struning EL, Shrout PE, and Dohrenwend BP (1989) A modified labeling theory approach in the area of mental disorders: An empirical assessment. American Sociological Review 54: 100–123.

- Link BG and Phelan JC (2001) Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology 27: 363–385.

- Major B and O’Brien LT (2005) The social psychology of stigma. Annual Review of Psychology 56: 393–421.

- Parker P and Aggleton P (2003) HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: A conceptual framework and implications for action. Social Science and Medicine 57: 13–24.

- Rahman N, Mubbashar M, Gater R, and Goldberg D (1998) Randomised trial impact of school mental-health programme in rural rawalpindi, Pakistan. Lancet 352: 1022–1026.

- Scheff TJ (1966) Being Mentally Ill: A Sociology Theory. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

- Thornicroft G (2006) Shunned: Discrimination Against People with Mental Illness. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Watson AC and River LP (2005) A social-cognitive model of personal responses to stigma. In: Corrigan PW (ed.) On the Stigma of Mental Illness: Practical Strategies for Research and Social Change, 1st edn. Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

- Yang LH, Kleinman A, Link BG, et al. (2007) Culture and stigma: Adding mood experience to stigma theory. Social Science and Medicine 64(7): 1524–1535.

- Corrigan PW (2004) How stigma interferes with mental health care. American Psychologist 59(7): 614–625.

- Corrigan PW and Gelb B (2006) Three programs that use mass approaches to challenge the stigma of mental illness. Psychiatric Services 57(3): 393–398.

- Herek GM (1999) AIDS and stigma. American Behavioral Scientist 42(7): 1106–1116.

- Keusch GT, Wilentz J, and Kleinman A (2006) Stigma and global health: Developing a research agenda. The Lancet 367: 525–539.

- Lee S, Lee MTY, Chiu MYL, and Kleinman A (2005) Experience of social stigma by people with schizophrenia in Hong Kong. British Journal of Psychiatry 186: 153–157.

- Link BG, Yang LH, Phelan JC, and Collins PY (2004) Measuring mental illness stigma. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30(3): 511–541.

- Markowitz FE (2005) Sociological models of mental illness stigma: Progress and prospects. In: Corrigan PW (ed.) On the Stigma of Mental Illness: Practical Strategies for Research and Social Change, pp. 129–144. Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

- Mead GH (1934) Mind, Self and Society. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Phelan JC (2005) Geneticization of deviant behavior and consequences for stigma: The case of mental illness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 46: 307–322.

- Phelan JC, Link BG, and Meyer J (in press) Stigma and discrimination: one animal or two? Social Science and Medicine.

- Yang LH and Kleinman A (in press) Face and the embodiment of stigma in China: The cases of schizophrenia and AIDS. Social Science and Medicine.

- http://www.repsych.ac.uk/campaigns/changingminds.aspx – Changing Minds, an anti-stigma campaign against mental illness, which is funded by the United Kingdom Royal College of Psychiatrists.

- http://www.eufami.org – The European Federation of Associations of Families of People with Mental Illness.

- http://www.hivaidsstigma.org – Ford Foundation’s HIV/AIDS Anti-Stigma Initiative.

- http://www.stigmaconference.nih.gov – National Institutes of Health Stigma Conference, 2001.

- http://www.openthedoors.com – World Psychiatric Association’s international effort to combat the stigma of schizophrenia.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.