This sample Transition to Universal Coverage in Developing Countries Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Paying For Health Care And Pooling Risk

Paying For Health Care

Individuals pay for medical care in two ways: Directly in return for service or, indirectly, through payment in return for an entitlement to treatment if sick. Direct payments include user charges paid around the time of illness; savings-based schemes, where users pay ahead of time; and loan schemes, where payment is deferred until after treatment. Savings schemes include provident funds that are often offered to civil servants in developing countries and medical savings accounts, used in Singapore, China, and some states in the United States. Prepayment systems have the advantage over user fees that people do not face large bills when they are sick but can spread the cost of care over their lifetime. They may be viewed as an interim stage in the progress towards inter-personal risk pooling.

Indirect payments, or insurance entitlement, cover a much larger potential cost of treatment than is reflected in the contribution but is only effective in the event of illness. Contributions from members reflect the costs of the scheme including administration, contingency, and cost of treatment. The serious and financially catastrophic nature of some illnesses means that risk pooling is preferred, particularly for payments for major illness. A latent demand for insurance is indicated in the observation that individuals tend to be risk averse. This means that if offered the choice between a certain income and an uncertain, but mathematically equivalent, expected income, they prefer the certain option.

Indirect payment systems can be provided through explicit insurance, where members knowingly pay contributions in return for coverage, or through implicit insurance, where coverage is financed by taxation for part or all of a population (see WHO, 2000: Chapter 5). With implicit systems of insurance coverage, citizens or residents or a particular community are covered regardless of whether they make a contribution. These are mainly financed out of general taxation. Universal funding is closely linked with the ability to administer a system of taxation. While most OECD countries collect more than 30% of GDP in taxes, in low-income countries the figure is usually less than 20% and sometimes as low as 5%.

Explicit systems tend to limit coverage to those that have made a contribution or to those where the contribution is explicitly financed from another source. A variety of explicit systems exist. One type is voluntary commercial insurance organized by the private sector, on a profit or non-profit-making basis, as a service for paying contributors. In order to maximize profits and minimize the problem of adverse risk selection (see below), contributors are charged a premium related to their risk status (risk rating).

Another type of financing is social health insurance, which differs from private insurance in that it is generally offered on a noncommercial basis and financed from compulsory deductions from employee wages. Employers and government may also make a matching contribution. Social health insurance is usually instituted by government but can be managed by nongovernment bodies such as employment-based organizations, unions, or locally based mutualities. Government may finance the elderly and poor, while insured members often cover dependants. Even though contributions are related to income or wages, the adverse selection problem is avoided by making the scheme compulsory for a well-defined group of the population.

Social insurance is based on the existence of an identifiable payroll and on a relatively stable workforce. Yet the context in many middle and low-income countries is that the workforce is transient, employment is casual, and no formal payroll exists. In addition, there is often a distrust of the state and considerable avoidance of taxation. Community insurance offers a slightly different way of developing risk coverage. Although there are many types of community schemes, most provide a limited package of benefits, often restricted to local facilities and limited referral, and based on voluntary enrollment on payment of a flat rate premium. The schemes have much in common with those offered by friendly societies and mutualities in Europe during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Adverse selection is an important issue since the scheme is voluntary.

Organized health financing mechanisms also have other important functions that can be achieved only by pooling contributions for health care. One function is to finance the cost of public health interventions or treatments that have significant externalities. Positive externalities are where treatments benefit people in addition to those actually using the service; an example is the additional protection afforded to members of the community as a result of a vaccination against a disease.

A further role of organized state funding is as a mechanism for income redistribution by transferring resources from the healthy who are often also relatively wealthy to the sick and impoverished. This is achieved in systems that base contributions on income such as social insurance and universal systems based on progressive or proportional taxation regimes. There is less scope for redistribution in voluntary community schemes where contributions are generally flat rate. Income redistribution plays no part in commercial systems of insurance.

Another important function of organized risk pools is to provide a stimulus for active purchasing. This term describes a range of tools used to induce improvements in the effectiveness and efficiency of provision such as selective contracting, quality assurance, treatment protocols and provider payment incentives. These tools may be used both by social and private insurers in order to extract better value for resources used. Closely related are means to control consumer demand in order to improve the distribution of services toward those most able to benefit or in most need. Tools include access rules such as primary care gatekeepers, prioritization of services, and waiting lists.

Technical Concerns In Extending Coverage

Extending health insurance cover to a population – however financed – raises a number of practical issues. The first, adverse risk-selection, relates to the method of assessing contributions. This problem arises because people often know more about their risk status than does the potential insurer: Individuals know if they have a chronic condition, have been ill in the past or have a lifestyle habit, such as smoking, that predisposes them to more illness. As a consequence, a voluntary system with income or flat-rated contributions tends to attract high-risk individuals and to deter those who are at low risk from joining the scheme. This disturbs the central objective of insurance, which is to pool risk between risk types, and can lead to a substantial increase in premium for those that are still willing to join.

The private sector solution to adverse risk selection is to base premiums on risk rather than income. This increases the cost of insurance to those more likely to get sick who are also often in lower income groups. Since many people cannot afford risk-rated insurance, commercial insurance is not a good way of extending universal coverage.

The problem of adverse risk selection means that the most reliable way of extending coverage to a population is by making insurance compulsory. Contributions can then be based on ability to pay.

Further technical issues concern the practical difficulties of identifying potential members, assessing contributions, and collecting premiums. These difficulties are particularly acute where communities are not based on well-defined static groups such as formal employment. Where coverage is compulsory, all three issues are pertinent in developing a solidarity-based system. Where coverage is voluntary, identification is mainly a matter of marketing the scheme and selling policies to those that require cover.

Sustaining the finance for a scheme is important for the long-term development of coverage. Contributions must be based on an accurate assessment of the risk of those insured. To cover unexpectedly large costs, calculations must build in the accumulation of a reserve. Since the probability of incurring greater than average costs diminishes with the number of contributors, large insurance groups are much less at risk than smaller groups. This is a particularly important issue for smaller community funds, which are highly exposed to such uncertainty. Some state systems operate on a cash limited pay-as-you-go basis, which rations the level of care according to the amount of funds available.

Another issue that affects the sustainability of extending coverage is the excess use associated with care that is free to patients at point-of-delivery. This problem, known as moral hazard, has been particularly important in OECD countries that have invested substantial technical resources in minimizing its effects. The problem is exacerbated where providers are paid in direct proportion to levels of activity since neither consumer nor provider has an incentive to contain demand. In recent years both the Czech and Korean systems have suffered from rampant increase in costs resulting from this problem.

What Is Universal Coverage?

Universal coverage can be described as the attainment of complete insurance coverage of a population for the costs of a specified package of priority health care. The target has two dimensions described by Kutzin as breadth and depth (Kutzin, 1998). Breadth refers to the proportion of a population group covered by the insurance scheme; the target is 100% of all citizens or permanent residents of a country. Depth relates to the types of service included in the benefits package. There is no absolute benchmark, although a guide is provided by the ILO’s 1952 Social Security Convention, which specifies the minimum coverage to be provided under a social security scheme. This includes:

- general practitioner care, including home visits;

- specialist care in hospitals and similar institutions for inpatients and outpatients and such specialist care as may be available outside hospitals;

- essential pharmaceutical supplies;

- prenatal, confinement, and postnatal care by medical practitioners or qualified midwives;

- hospitalization where necessary.

The definition emphasizes levels of care whereas other approaches place greater emphasis on the types of illness for which treatment should be offered and the treatment technologies themselves. A further refinement is to restrict coverage to those technologies that are proven to be effective or cost-effective. Faced with the rapidly increasing availability of new drugs and technologies, such evaluation is increasingly being carried out in countries including Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom.

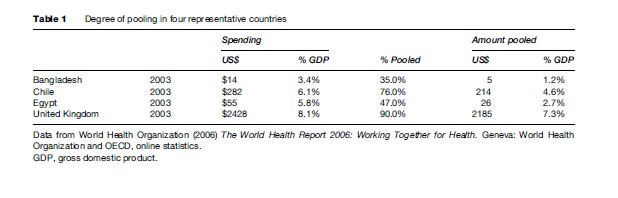

In most cases, the transition to universal coverage cannot be accomplished quickly. A number of factors are important. Given that total spending on health care is mainly determined by the macro-economy, the most important question is whether total resources available are sufficient to match the needs of universal coverage. A second factor is whether a sufficient proportion of total spending on health care can be channeled to finance a core package. Both questions are of importance in low and middle-income countries. While average health spending in the OECD is around US$2500 per capita (unweighted average in 2004 at purchasing power parity; see OECD website), in low-income countries spending is less than US$15. In addition, most low-income countries pool a much smaller proportion of total health-care spending. A rich country such as the United Kingdom, for example, pools more than $2400 per capita, whereas a low-income country such as Bangladesh pools around $5 per capita (see Table 1).

Countries that are not able to afford an ILO-style package sometimes specify a lower level of coverage that can be financed on a universal basis from public funds. This is the central concept behind the package of essential services described in the 1993 World Development Report (World Bank, 1993). This report suggests concentrating public funding on a small number of highly cost-effective services. It is important to realize that many of these services are of a public health or primary care nature and high-cost curative hospital services are mostly not included. Additional services are then financed by individuals using voluntary insurance or in the gradual addition of groups covered by more extensive, social or voluntary, insurance.

The high-breadth, low-depth issue is particularly acute in those low and middle-income countries that claim to offer universal coverage on the basis that all citizens can walk into public health facilities and obtain consultation and treatment without official payment. Shortage of resources often means that people must wait long periods or make additional unofficial payments before treatment is forthcoming. This has been common in many postcolonial countries of Africa and South Asia that have attempted to extend systems inherited from their colonizers but without the resources to make the claim to comprehensive cover truly effective.

Paths To Universal Coverage: OECD Countries

The extent to which countries have achieved universal coverage varies enormously across the world. Those countries that have the most well-established and stable risk-pooling systems are predominantly concentrated in the OECD. (Much of this discussion focuses on the original members of the OECD: Western Europe, North America, Australia, and New Zealand. Later members only partly fit this profile.) A characteristic of the transition in these countries has been the gradual development of coverage. While it is tempting to focus on key events – the 1883 Insurance Act in Germany or the 1946 National Health Service Act in the United Kingdom, for example – these events might be seen more as milestones in a much longer process of transition.

Most established market economies extended risk coverage through compulsory insurance for employees and later their dependants. Beyond this there is a dichotomy. First, there are countries that base coverage on the gradual filling of gaps in existing coverage based on explicit insurance. Second, some countries have chosen, at some point, to legislate for 100% coverage financed from general taxation (implicit insurance). Those taking the latter route have generally first reached a significant level of explicit coverage of the population. It is important to recognize that while the explicit approach is less dramatic than the implicit, universal approach, it still requires committed and sustained policy effort.

Germany

The foremost example of the explicit insurance approach is the German system. Often known as the Bismarck model after the nineteenth-century German Chancellor (Count Otto von Bismarck, 1815–1898), it is based on coverage through compulsory membership of employment-related risk pools financed by wage-based contributions. This is referred to by Mesa Lago as the social insurance approach, with separate programs for different risks such as unemployment, old age pensions, and sickness (Mesa-Lago, 1991).

The impetus to universal coverage was the 1883 Insurance Act, which made social insurance compulsory for certain categories of workers. Much of the social legislation of Bismarck, including this act, was part of an orchestrated attempt to undermine the allure of socialism by providing workers with a broad welfare safety net. The main focal group was industrial workers who, together with the trade unions they joined, were most influenced by the wave of social democratic sentiment. An added benefit was that it was easier to collect contributions from this relatively well-paid group in steady employment.

The 1883 act prepared the ground for the extension of coverage but built on a variety of existing organizations and legal obligations. Trade guilds traditionally offered assistance to vulnerable members to finance funeral, food, and housing expenses. Employers were legally responsible for the cost of accidents to employees, although this often placed an unsustainable burden on smaller enterprises. Employees also found that the requirement to prove liability meant that obligations were often not met. Furthermore, poor relief, which was the responsibility of manorial estates, often put a considerable strain on these rural communities. Thus while legislation was not uncontentious and its urgency arose from political expediency, it was undoubtedly assisted by the way in which it relieved burdens at the same time as imposing new obligations on employers, workers, and the state.

Initially the insurance act covered approximately 26% of blue-collar employees, roughly 10% of the population. Civil servants were covered in 1914, the unemployed in 1918, and self-employed agricultural workers in 1972. Students were not included until 1975, 92 years after the original act. Today less than 0.1% of the population is without cover. Reforms introduced in 2007 will mean that by 2009 coverage will be mandatory for all residents either through private or social insurance – 125 years since the original insurance act.

The system is financed from compulsory contributions for those in employment. Solidarity between rich and poor was assured by the compulsory nature of the system, although an opt-out for the better-off was permitted from 1914.

Following Germany, both Austria (1888) and Hungary (1891) enacted legislation on a similar basis. France also followed a social insurance model but retained an important role for top-up insurance provided by mutual insurers. Switzerland for a long time rejected similar legislation and it was not until 1996 that health insurance became universal.

United Kingdom

An alternative path to universal coverage is to legislate for 100% cover by including all groups based on citizenship or residency rather than contribution. This is sometimes known as the Beveridge model after the civil servant W.H. Beveridge, who designed the British system introduced after the Second World War. It is important to note, however, that several other universal systems, notably the system in New Zealand, actually predate legislation in the United Kingdom.

In the United Kingdom, the 1946 act was the culmination of more than a century of change in the approach to financing health care. The system in the UK could easily have followed the German model. Social policy during the nineteenth century focused on punitive welfare designed to encourage workers out of poverty. Ever since the Middle Ages, the parish had responsibility for providing poor relief, which was consolidated through revisions to the Poor Law in 1834. An enlightened policy toward the improvement of public health was largely pursued on the grounds that ‘‘labourers are suddenly thrown by infectious disease into a state of destitution’’ (Edwin Chadwick, public health reformer, 1800–1890). For the same reason, the Poor Law benefit was restricted to discourage indigence.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, while public health had largely been included in the duties of the state, coverage for personal health care was still extremely fragmented. For the rich, treatment was paid for by commercial insurance and out-of-pocket payments. For those on low incomes, there were free Poor Law (public) and charitable hospitals to which doctors gave some of their time without charge. For the aspiring working class, the friendly societies organized provident funds for health and funeral expenses. By the end of the nineteenth century, however, many of these were in financial trouble as members were living too long and payouts exceeded contributions.

A major departure from the Victorian emphasis on morality was articulated by Winston Churchill, then President of the Board of Trade, who advocated a principle of universality rather than attempting to distinguish between deserving and undeserving poor. Both Churchill and David Lloyd-George (Finance Minister, later Prime Minister) favored a broad social insurance package, similar to that adopted in Germany, which eventually became universal. The National Insurance Act of 1911 was more circumscribed, including sickness benefit, primary care contacts, and some specified services such as TB sanatoria but no general hospital benefit. One reason was the severe opposition from both professions and friendly societies. The latter were clearly threatened by this state intrusion on their virtual monopoly over prepayment for health care. Another reason was that a comprehensive benefit was simply not affordable at that time.

Interclass solidarity that built up during the Second World War provided the much needed impetus to the creation of a universal insurance system institutionalized in the National Health Service (NHS). The 1942 report on social insurance and allied services, known as the Beveridge report after its main author (William H. Beveridge, 1879–1963), sketched out the fundamentals of the modern welfare state. The central principles were comprehensiveness, contributions related to means, and benefits based on need. Importantly, and in contrast to Germany, the envisaged system integrated both financing and provision of care.

The universal, implicit insurance approach has also been adopted in New Zealand where coverage was extended first for inpatient care (1939) and subsequently outpatient and pharmaceuticals (1941). Sweden legislated for universal coverage in 1953 followed by other Scandinavian countries (Norway 1956; Finland, 1963; Denmark, 1971; Iceland, 1972). Canada (1966) and Australia (1974) followed with similar legislation. More recently, legislation has been introduced in the southern European countries of Portugal (1978), Spain (1978), and Italy (1980).

Russia

In Russia, parallels to the German experience were recognizable in the late nineteenth century. The state, as part of a general policy of liberalization, intervened in the funding and provision of services. Following the emancipation of the serfs, a medical system was integrated into the local government structure that provided polyclinic and inpatient services. The 1912 Insurance Act, introduced during the Fourth State Duma, placed an obligation on employers to bear the costs of accidents, sickness, and death of employees and dependants. As in Germany, these benefits were aimed to assuage the demands of an increasingly militant labor movement. But this was too little too late, and the revolution led to a much more fundamental transformation of medical care.

The Soviet system that developed following the second revolution of 1917 was greatly influenced by the physician A.N. Semaschko (1874–1949) who was head of the Central People’s Commissariat of Health from 1918. The nationalized health service, as in other sectors, placed emphasis on the contribution of medicine to the process of industrialization. Party congresses continually laid great stress on the productivity losses arising from illness. As a result, the three separate subsystems of industrial medicine and public health, adult medicine, and pediatric care developed. Specialized polyclinic care provided the entry point and the system remained highly specialized and horizontally segregated when patients were referred. The rural health service, created during the late czarist regime, remained and was eventually integrated into the Semaschko system.

Although the system evolved during the 1920s, it was not until 1935 that a centralized structure was finally agreed, creating the Ministry of Health as supreme administrative body. The head of the Ministry, always a doctor, was made a permanent member of the cabinet. The Semaschko system was used throughout the Soviet Union and, in modified form, in most of Eastern Europe.

General Trends In Establishing Universal Coverage In The OECD

A number of general features are evident in the transition to universal coverage across the OECD.

- Developing universal coverage was a slow process. Building upon medieval structures, it took up to a century to extend coverage to much of the population of Western Europe.

- Indigenous mechanisms for risk pooling existed in all countries and attempts to extend coverage built on these systems. This is exemplified in the integration of the friendly societies into the administration of national insurance after the First World War in Britain and incorporation of the mutuelles in France. The latter still have an important role today in providing supplementary insurance.

- Historic obligations on local authorities to provide Poor-Law relief and on employers to provide accident and sickness assistance promoted the need to create more effective structures for risk pooling. It is also noticeable across Europe that while a number of institutions provided the basis for a developing system of social protection, state intervention was required to unify, and sometimes pacify, disparate forces.

- The administration of the provider network changed relatively little with the development of universal coverage. The major exception is the UK, which nationalized its system after the Beveridge reforms, and the Soviet Union where the entire system was taken into state hands.

- In almost all OECD countries, near universal coverage required substantial state involvement. Intervention ranged from the regulation of funds and their redistribution in social insurance systems to the integrated systems common in Scandinavia, New Zealand, the UK, and southern Europe. The United States stands out as the only one of the original members of the OECD with substantially less than universal coverage.

- Political factors were of considerable importance as a catalyst to the development in a number of countries. German social insurance was initially designed to reduce socialist opposition, while the social reforms of the Russian Fourth Duma were designed to do the same for communism. Social insurance in Italy between the wars was seen as a way of reinforcing the classlessness espoused by National Socialism. The Beveridge reforms partly came from a sense of solidarity generated by the Second World War.

- Those systems legislating for universality had already achieved coverage of the overwhelming majority of their population. The cost of extending coverage, in addition to social and political factors, prevented some systems from establishing universal coverage even earlier.

Paths To Universal Coverage: Developing And Transitional Countries

Coverage of developing and transition countries is generally much lower than in the OECD, both in breadth and depth. There is considerable diversity across countries.

Latin America

Much of Latin America has adopted the social insurance model as a way of developing coverage between groups. The region, encouraged by the International Labour Organization (ILO), began to introduce social insurance soon after the First World War. Mesa-Lago identifies three waves of activity. In the first wave, the pioneer countries Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Uruguay, and Cuba introduced insurance on a piecemeal basis beginning with civil servants followed by formal blue and white collar workers in key large-scale industry: Transport, energy, banking, and communications. Schemes were later extended to other urban workers, agriculture, and the self-employed. The result was a series of schemes offering very different packages. Key industries and civil servants received more substantive coverage than other groups. Subsequently, this made unification of the schemes difficult: Leveling up to the best plan has proved too costly, while a reduction is resisted by those with more comprehensive cover.

In Argentina, social insurance was based, until recently, on compulsory contributions by workers and employers to union-administered funds (Obras Sociales). There are more than 300 funds, although the largest 30 account for more than 70% of members. Many of these originated in the nineteenth century. The schemes cover both workers and their dependants. In addition, there are funds in each of the 23 provinces to cover public workers. A separate organization covers retired workers.

A number of problems have been identified. One is the monopolistic nature of the funds since employees were often obligated to obtain insurance from sometimes inefficient schemes. Another is the substantial difference in level of remuneration offered with the result that members of poorer funds are forced to make significant out-of-pocket co-payments for treatment. New mechanisms to guarantee minimum funding, through a redistribution fund, were approved in 1994. Attempts are also underway to establish a minimum package of services to be guaranteed by each fund.

Chile was one of the first countries to introduce social insurance in the 1920s. Starting in a traditional way with insurance for workers in industry, by 1970 approximately 75% of the population were covered. As in the Argentinean system, there were substantial variations in benefits between groups. Nonmanual and, in particular, government workers generally had access to better quality services than manual workers.

Major changes were introduced by the Pinochet government, which attempted to widen the role of the private sector by allowing people to opt out of the social insurance system and purchase private coverage. This undermined the solidarity principle of risk pooling across income and risk groups. Those insuring privately are predominantly low-risk, wealthier employees. This group is able to obtain attractive coverage, choosing between a wide range of providers at relatively low premiums. The elderly, chronically ill, and very young are generally more expensive and less profitable and are mostly covered by the public insurance fund. Combined with general reductions in public funding for health, this has reduced the quality of the public service, creating a two-tier system. Drop-out from the public system in Chile has been much greater than in other countries that permit opt-outs. One reason is that whereas in the Netherlands and Germany opt-outs are only permitted above a certain income, the Chilean system permits opt-outs at any income.

Brazil is the only country in Latin America to legislate for universal coverage. This followed the development of employment-based social insurance coverage. The 1988 constitution introduced the Unified and Decentralized Health System (SUDS) and established a citizen’s right to use any public health service in the country. Various factors have restricted the depth of coverage. Fundamental to this are the large geographic differences in economic status across the country. Central government provides funding to states based on size of population, which are then supplemented from local resources. Poorer states are unable to top-up to the same degree as wealthier states and the result is large differences in effective cover.

A second wave of social insurance adoption commenced in the 1940s heavily influenced by the International Labour Organization (ILO). The countries involved – Mexico, Colombia, Peru, Panama, Ecuador, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Venezuela – were relatively developed but still predominantly rural economies. Coverage has closely followed the industrialization of each economy. The Mexican social security system, for example, currently covers around 50% of the population, mostly formal employees and their families. The remainder have access to the state-run system or, for those able to pay, to the extensive network of private facilities. Unlike Brazil, where people now have access to a wide variety of facilities, the Mexican system remains vertically integrated, with social security facilities reserved for those who are covered under the scheme. Considerable discussion is now underway regarding ways to achieve near universal coverage through, for example, publicly subsidized access to an essential services package aimed at the uninsured, in particular the poor (Frenk et al., 2007).

A final wave of insurance coverage expansion during the 1950s and 1960s is evident in poorer countries of the region. The group includes Dominican Republic, Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Honduras. Extension of coverage is hampered by the low levels of GDP, a relatively small industrial workforce, and a scattered rural population.

Former Soviet Union And Eastern Europe

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, there has been widespread adoption of entitlement-based social insurance across the region. The trend is important because it represents a move away from the Semashko system that, in theory, already offered universal coverage. The transition is based on the growing reality that depth of cover has, in reality, never been comprehensive. Furthermore, it has been deteriorating in recent years. The system probably always offered a two or even three-tier service. Party workers – the nomenclature – received the highest standard of service, followed by industrial workers in key sectors, with the remainder of the population receiving a varying quality of services often based on what they were able to trade in return.

A number of motives were apparent in the development of insurance legislation. Of paramount importance was the need to provide additional and earmarked funding for health care. Another reason was to improve the efficiency of provision through the selective contracting of services by nascent insurance funds. In theory this can motivate competition between providers for insurance fund contracts and so improve the efficiency of the system. It is possible, in principle, to create a split through a division in organizational responsibilities within a country’s ministry of health. In countries where highly centralized control has been the norm, as in the Former Soviet Union (FSU), this separation can prove difficult. Establishing a fund creates a split between the purchaser of care (the insurance fund) and the providers, a change that may enable the system to respond to consumer needs rather than the concerns of providers.

A further development in some FSU countries has been to encourage the creation of a competitive market in which social insurers, like private insurers, compete for business. For competition to exist, employees must have a choice of a number of funds. The employee and employer contribution is then allocated to the chosen fund. This objective of competition was pursued most vigorously in the Russian Federation where the design of the new system allowed people to choose between competing funds. In practice, however, this competition often does not function effectively because employers make the decision regarding which fund to enroll workers into or because only one fund operates in a given geographic area.

A key problem with the imposition of social insurance in the FSU was that it imposed a burden in the form of a health tax on employers just at the time when many were already suffering from the impact of economic transition. Newly created insurance agencies expected to improve the quality of services. Yet the funds were often ill equipped to induce a fundamental change in the provider system. Some evidence in Russia, where regions have developed insurance at differential speeds, suggests that even in the most advanced regions the insurance funds have little changed the way in which they purchase services (Twigg, 1999).

A weakness of the development of insurance in FSU countries has been a failure to address the issue of declining risk pooling for health care. A characteristic of all the countries has been increasing out-of-pocket payments, official and unofficial, and a contracting formal workforce. Since dissolution of the Soviet Union, most economies have experienced a significant contraction in their economies in real terms – between 10% and 90% across the region – and a break-up of state industries. Yet the reforms offered were based on organizational mechanisms to cover the formal, largely state, sector based on a payroll tax. Particularly in the poorer states of the FSU – Central Asia and the Caucuses – formal insurance may not have addressed the economic realities of increasing unemployment and fragmentation of the labor market. Social insurance has appeared to take root relatively successfully in the wealthier and highly industrialized countries of Eastern Europe: Hungary, the Czech Republic, and the Baltic States. All have formal industrial sectors exceeding 70% of total employment.

Low-Income Countries

A key feature of most low-income countries (average GDP $410 per capita, 1999) is that funding for health care is dominated by direct payments for care. More than 59% of spending on health is estimated to be private, the majority out of pocket.

In most Sub-Saharan African and low-income Asian economies, the main source of pooled funding is direct taxation (supplemented by donor funding), which is used to finance a publicly managed health center and hospital system. These public systems tend to be underfinanced and access favors urban residents and higher income groups. Many governments now attempt to prioritize certain services that are particularly cost-effective, such as public health care. The strategy may have a considerable impact on population health, but it still leaves individuals exposed to the risk of high-cost catastrophic illness.

Extending risk pooling to populations in low-income countries has followed a number of routes. One is through traditional work-based social insurance. A variety of countries have extended payroll-based insurance to the public and private formal sector. The problem is that in most low-income countries these sectors are extremely small, perhaps constituting 6–10% of the population. Another issue is that even for formal employers the obligations to provide health care and protect employees from accidents may be absent or not enforced. As a consequence, there is little incentive for employers to seek to develop insurance coverage for their employees. Those that tend to benefit most are civil servants who, as a relatively privileged subgroup, have less exposure to catastrophic financial risk. They are also male-dominated since the majority of civil servants and formal sector employees are men, although coverage of families widens coverage somewhat.

In almost all sub-Saharan countries (excluding South Africa), formal sector insurance covers less than 5% of the population. The exceptions are Kenya, which has a formal sector scheme that includes dependants covering around 25% of the population, and Senegal and Burundi that cover public sector workers constituting perhaps 10–15%. A number of African countries are now attempting to extend social insurance to a wider population. In Kenya, action has begun to enlarge the existing base of formal sector workers and civil servants to include a larger number of small enterprises and self-employed workers. In Ghana, a system that ties together an existing social insurance scheme for formal workers with district-based mutual insurance for the rural population subsidized by taxation is now being introduced (Appiah-Denkyira and Preker, 2007).

A similar situation characterizes low-income South Asian countries. In Bangladesh and Pakistan, social insurance is limited to a variety of provident funds for civil servants, although the formal sector is increasingly turning to the private sector for health insurance coverage for employees. All these countries maintain an extensive but often decaying public system open to all on payment of unofficial payments, and a vibrant private sector offering almost anything on a fee-for-service and largely unregulated basis.

Patterns Of Transition

In recent times, both Korea and more recently Thailand have taken the step of legislating for universal coverage. The problems arising offer interesting lessons for the extension of coverage in other lowand middle-income countries.

South Korea

One of the most dramatic extensions of coverage is recorded in South Korea. A voluntary insurance law was passed in 1963, but by 1977 less than 9% of the population was covered. From 1977 compulsory insurance was gradually extended, at first to large enterprises, through employment and area-based insurance societies. Later coverage was extended to civil servants (1978), smaller companies (from 1981), the self-employed (1981), and other rural workers. A separate scheme for the poor was also established based on strict eligibility criteria. By 1987, almost 60% of the population was covered by one of the schemes and in 1989 health insurance was made compulsory for all long-term residents of the country.

Korea is an example of a system that has achieved good breadth of cover in a short period. An important factor was rapid economic growth that averaged more than 10% from 1970 to 1990, while the proportion of the labor force working in agriculture fell from more than 49% to 18%. Some of the growth in breadth was at the expense of depth of coverage. Insurance funds include all the items mentioned in the ILO social security convention, although some expensive diagnostics such as MRI and PET are excluded (until 1996 CT was also excluded). Significant copayments are, however, an important feature of the system. Users contribute between 30% and 55% of the cost of ambulatory care and 20% of the cost of inpatient care. A monetary limitation is also placed on the reimbursable cost of each 30-day period of illness. The substantial copayments are partly the consequence of regional economic recession toward the end of the 1990s. They can also be traced back to the fee-for-service basis for remuneration, which has made cost containment difficult.

Thailand

In Thailand, from the 1970s, and more strongly from the early 1980s, voluntary insurance was extended to a largely rural population by marketing health cards. Later this movement lost ground when the initiators left office. More recently, the scheme has been revived and developed into a national scheme covering approximately 50% of the target group. Social insurance (Social Security Scheme, SSS) was introduced for the formal sector in 1991 and has been progressively extended to smaller companies. A separate scheme for civil servants, including teachers and medical staff, is financed fully by the government. Finally, a system of public assistance has been extended to those on low incomes.

In 2001, a new government was elected promising to combine the schemes and make coverage universal. Unification is difficult because of the varied contributions and benefits provided to members of the different schemes. By 2000, all schemes covered roughly 70% of the population, although offering uneven depth of coverage. The contributions for the scheme for civil servants, which are paid fully by government, for example, are ten times the contributions paid for the voluntary health card scheme. While both civil servants and SSS members have access to public and private facilities, health card and public assistance members were restricted to public facilities. Since 2001, while the schemes for civil servants and employees remain separate, a universal scheme has replaced health cards and the scheme for the poor to cover the remainder (74%) of the population. Recent studies indicate that this scheme is progressive in targeting benefits toward those with lower incomes, particularly at the lowest levels of the system and financed by those most able to pay (Tangcharoensathien et al., 2007). The study suggests that this is largely because of the heavy role played by general taxation in the financing of the scheme.

China

A reverse process of transition is evident in China. Three schemes were established during the 1950s: The Government Employees System (GIS), the Labor Insurance System (LIS), and Cooperative Medical Schemes (CMS). Until 1980, universal coverage in China in rural areas was ensured through the CMS, financed out of commune funds. Members were entitled to free outpatient and inpatient care as well as medicines. By 1979, more than 90% of the rural population were covered by CMS. In urban areas, the LIS and GIS provided protection for most industrial sector employees.

In the early 1980s, there was a rapid collapse in CMS. A number of factors have been suggested, including the market reforms of Deng Xiaoping (1904–1997), which introduced individual rather than collective responsibility for agriculture and an erosion in commune funds, increased income opportunities for medical workers, and the demand by farmers for more sophisticated and costly services. At the same time, medicine in both urban and rural areas has become increasingly market-oriented. This has led to rapid cost escalation and a deterioration in access to services by vulnerable parts of the population. Trends suggest a reverse process, with coverage of the population deteriorating, a decline in risk pooling, and greater reliance on direct payments for health care. While the catalyst to change has been economic, the process itself indicates the importance of retaining the support of society. The difficulty in recapturing a sense of community solidarity, through the reinvention of the CMS system, has proved difficult given the general distrust for state-run social schemes. There is now a new attempt to restore some government credibility through the establishment of a new CMS that will be run both with individual contributions and matching contributions from local and central government.

Risk Coverage For The Informal Sector

The speed toward universal coverage is likely to vary enormously according to country context. Studies examining the historic transition agree that there are a number of key facilitating factors, including a fast-growing economy, a high level of formalization and industrialization of the workforce, urbanization, good governance, and a high level of social solidarity (Ensor, 1999; Carrin and James, 2005). Yet in many low-income countries, these conditions will not exist for many years. Indeed, the difficulty involved in extending social insurance mechanisms to a wider population has led to alternative approaches. These are usually based on networks that exist outside the formal industrial sector: Specific communities, occupation, or social groupings. In principle, schemes can be voluntary or compulsory. A number of countries, including Korea and Taiwan, have now developed organizations and levels of economic development that permit them to make the schemes compulsory for the entire population.

Compulsory insurance for the informal sector in many low and middle-income countries is made difficult because individuals can often evade contributions as they do other taxes. Many cannot afford premiums and the potential benefits, in terms of existing local health services, do not provide adequate compensation for their contribution. In response to this, a variety of voluntary systems, collectively known as community insurance, have developed. In general, these approaches are based on voluntary enrollment, usually, but not always, based on a fixed premium. These offer clearly identified benefits that are highly valued. Beyond this, there is remarkable diversity in approaches both in the services covered and in the way they are set up to attract enrollees. Some offer primary care only, while others include referral services.

A few voluntary schemes succeed in covering the majority of the population in a given area. The Bwamanda scheme in the Democratic Republic of Congo (former Zaire) covers more than 60% and Goalpara in India 90%. One study found, in a survey of 62 schemes, that most schemes cover no more than 30–40% of the target group (Bennett et al., 1998).

Atim suggests that within the general category of insurance for the informal sector there exists a wide range of different types (Atim, 1999). These range from traditional social solidarity networks based on tribal or ethnic group through more inclusive mutual health associations. Both of these place considerable emphasis on participation in the governance of the schemes by members. This approach has been labeled micro-insurance (Dror and Jacquier, 1999). Individual micro-insurance schemes may be linked into networks to enable wider pooling of risks and shared training and management support structures. In essence, the approach attempts to get much closer to indigenous systems for developing risk pooling, with the aim that these are more likely to succeed than schemes that are imposed from the outside.

A separate approach has been for organizations running health-care facilities – government or nongovernment – to develop prepayment and insurance schemes to promote access to their facilities. A scheme may be established either by the facility management or the parent body, often an NGO. This is probably the dominant model in both Africa and Asia. Facilities may even make it compulsory for users to join the scheme before they can use facilities. The schemes tie the users to a particular type of care. Some provide for member involvement in running the scheme, although the majority do not.

In Bangladesh, widespread NGO-run micro-credit programs are being used to extend prepayment and risk pooling. A number of Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) now offer insurance to credit members providing low-cost access to their health facilities. Some organizations are investigating how these could be extended to coverage for treatment provided at referral level facilities. The nature of microcredit is that most members are women, although insurance coverage may also be offered to family members.

Schemes in both Thailand (in the 1980s) and Vietnam (in the 1990s) were initially launched by government at a national level, although they operated on different principles. In Vietnam, local pilot projects preceded countrywide implementation, but a national scheme was quickly introduced that allowed little local variation and provided unlimited benefits. In contrast, the Thai system permitted extensive local variation and involvement of communities. In many areas, it limited benefits to a maximum number of consultations in any year. The Vietnam scheme was launched simultaneously with a parallel scheme for the formal sector. While the formal scheme expanded quite rapidly, the voluntary scheme has achieved far less penetration.

Insurance for schoolchildren has been used by governments in several countries as a relatively low-cost way of enrolling children and their families into insurance schemes. Although sometimes thought of as a community approach, it is closer to formal-sector insurance in that the focus is on the semi-compulsory enrollment of all studying within a specified organization. School insurance is attractive since the population is easy to identify and contributions can be collected at a fixed time in each school. The group also tends to be quite low-risk since school children of ages 5–15 are some of the lightest users of medical care. In Vietnam, the mass enrollment of school children enabled the struggling insurance scheme to boost coverage at low cost in a short period (more than 3.4 million enrolled within 3 years). In Egypt, more than 70% of children are now covered by a similar scheme.

A number of design weaknesses have become evident in community insurance schemes. One is that the small scale of most schemes means that they cannot accumulate a sufficient reserve to pool unexpectedly large claims. Another is that the problem of adverse risk selection is endemic since flat-rate contributions mean that low-risk individuals tend not to join. In turn this leads to smaller, high-risk pools and greater costs. Finally, the administrative costs tend to be large. Bennett et al. found that administrative costs range from between 5% and 17%, although in some cases the amounts are much higher. They also point out that the costs usually cover only the basic administration of the scheme since the more sophisticated active purchasing function is generally absent.

In addition to technical issues, there are wider factors that relate to the extent which community insurance can stimulate change and promote universal coverage. One identified in the success of schemes has been the extent to which they take account of local institutions. This was the norm in Western Europe, where the development of social insurance often incorporated, at least initially, existing systems of risk pooling and took advantage of worker groups and employer obligations. This is not only a matter of involving some community members in governance but also involves taking account of context-specific factors that influence the desirability of particular forms of risk pooling. The success of one scheme in Cameroon, for example, has been attributed to the active participation of members in premium and benefit setting, a strong ethnic base, and the incorporation of other benefits valued by the community, including financial relief in the event of death. Conversely, imposing a scheme without taking account of indigenous social structures may lead to greater exclusion of people that, while part of the indigenous social network of mutual aid, are unable to pay for the imposed insurance system.

There is more scope for the insurer to promote system change if it is not strongly linked with a particular health facility but has the flexibility to negotiate with a range of facilities to secure low prices or higher quality. Most community schemes have not so far developed as strong purchasers of services. They tend to provide what consumers think they need – often medication – rather than attempting to rationalize service use. There are exceptions. Schemes such as those of the Sajida Foundation in Bangladesh and Bwamanda in former Zaire place an emphasis on preventive care, contracts with local facilities, and a strict referral system to higher levels.

Equity between and within community schemes is a major issue. While a network permits the creation of a large risk pool or enables a reinsurance function, the reallocation of funds from rich to poor schemes is hampered by the voluntary nature of association and membership. Even in China, where commune insurance was more or less compulsory until the early 1980s, evidence suggests large differences in the wealth of schemes. As a consequence, it is not usually feasible to expect large reallocations between schemes.

A further equity issue is the extent to which poor income groups are able to join the scheme. Some schemes, such as Gonoshastya Kendra in Bangladesh and MUGEF-CI in Coˆ te d’Ivoire, have a sliding contribution scale according to income. The problem is that overcoming adverse risk selection tends to militate against sliding fees on the basis that those with high incomes tend to have less need of care and the scheme would risk losing the low risk from the pool. In the context of schemes based on indigenous institutions, it may be that members are more willing to cross-subsidize. This is less likely in schemes imposed by external agencies where social alliances are weaker. It is probably inescapable that, in order to enroll a large proportion of the very poor, some form of external subsidy is required. One way to do this is through the provision of government purchased free cards, as occurred in Thailand and, to a lesser extent, Vietnam.

Conclusion

There are many ways in which a country can achieve universal coverage and each country’s experience is in one sense unique. At the same time, there are some clear patterns that emerge from the experience, particularly in the decision of whether to rely on an explicit entitlement approach or the more implicit approach based on residency. From a policy perspective, the role of government in facilitating the transition is crucial. This includes providing a legislative framework for mandating employers to provide social security for workers or opting into established state-run schemes, ensuring that the poor are provided with a basic guarantee of access, not only to essential services, but also insurance coverage for catastrophic expenses, and also in helping small community schemes to expand to cover the informal sector.

Extending coverage may sometimes imply a contradiction between encouraging indigenous schemes based on local institutions and scaling up for universal coverage. The latter tends to require more uniformity and consistency in contracts, which in turn may erode the traditional forms of social solidarity. One way forward is to accept that scaling will lead to changes in structure and that such changes impose a cost on members, and to make that cost acceptable. The benefits from change must exceed the costs. Government roles in the extension of insurance are often ambiguous. While government management of the scheme may damage the local participation and attractiveness of the scheme, a clear role is seen in the provision of technical advice, developing networks of schemes for reinsurance and other purposes, ensuring smooth entry and exit from the market, and subsidizing low-income members.

Bibliography:

- Appiah-Denkyira E and Preker A (2007) Reaching the Poor in Ghana with National Health Insurance – An Experience from the Districts of the Eastern Region of Ghana. Extending Social Protection in Health. Berlin, Germany: GTZ/ILO/WHO.

- Atim C (1999) Social movements and health insurance: A critical evaluation of voluntary, non-profit insurance schemes with case studies from Ghana and Cameroon. Social Science and Medicine 48 (7): 881–896.

- Bennett S, Creese A, and Monasch R (1998) Health Insurance Schemes for People Outside Formal Sector Employment. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Analysis Research and Assessment Division.

- Carrin G and James C (2005) Social health insurance: Key factors affecting the transition towards universal coverage. International Social Security Review 58: 45–64.

- Carrin G, Waelkens MP, and Criel B (2005) Community-based health insurance in developing countries: A study of its contribution to the performance of health financing systems. Tropical Medicine and International Health 10(8): 799–811.

- Dror D and Jacquier C (1999) Micro-insurance: Extending health insurance to the excluded. International Social Security Review 52(1): 71–97.

- Ensor T (1999) Developing health insurance in transitional Asia. Social Science and Medicine 48(7): 871–879.

- Frenk J, Knaul F, Gonzalez-Pier E, and Barraza-Llorens M (2007) Poverty Health and Social Protection. Extending Social Protection in Health. Berlin, Germany: GTZ/ILO/WHO.

- Kutzin J (1998) Enhancing the insurance function of health systems: A proposed conceptual framework. In: Nitayarumphong S and Mills A (eds.) Achieving Universal Coverage of Health Care, pp. 27–101. Bangkok, Thailand: Nontaburi Ministry of Public Health Thailand.

- Mesa-Lago C (1991) Social security in Latin America and the Caribbean: A comparative assessment. In: Ahmed E, Dreze J, Hills J, and Sen A (eds.) Social Security in Developing Countries, pp. 356–394. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Tangcharoensathien V, Prakongsai P, Patcharanarumol W, and Jongudomsuk P (2007) University Coverage in Thailand: The Respective Roles of Social Health Insurance and Tax-Based Financing. Extending Social Protection in Health. Berlin, Germany: GTZ/ILO/WHO.

- Twigg J (1999) Regional variation in Russian medical insurance: Lessons from Moscow and Nizhny Novgorod. Health and Place 5(3): 235–245.

- World Bank (1993) World Development Report 1993: Investing in Health Executive Summary. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- World Health Organization (2000) The World Health Report 2000, Health Systems: Improving Performance. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (2006) The World Health Report 2006: Working Together for Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Barnighausen T and Sauerborn R (2002) One hundred and eighteen years of the German health insurance system: Are there any lessons for middleand low-income countries? Social Science and Medicine 54(10): 1559–1587.

- Dror DM and Preker AS (eds.) (2002) Social re-insurance: A new approach to sustainable community health financing. Washington, DC: ILO and World Bank.

- Gertler PJ (1998) On the road to social health insurance: The Asian experience. World Development 26(4): 717–732.

- International Labour Organization (1999) Social Health Insurance. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Organisation/International Social Security Association.

- Nitayarumphong S and Mills A (eds.) Achieving Universal Coverage of Health Care. Bangkok, Thailand: Nontaburi Ministry of Public Health Thailand.

- Ron A and Scheil-Adlung X (2001) Recent Health Policy Innovations in Social Security. New Brunswick, NJ: New Jersey Transaction Publishers.

- http://www.ilo.org – International Labour Organization (ILO).

- http://www.OECD.org – Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

- http://www.worldbank.org – World Bank.

- http://www.who.int/health_financing – World Health Organization, Health Financing Policy.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.