This sample Information Privacy In Organizations Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

With descriptives like “the information age,” “the information super highway,” and “the knowledge economy”—popular in the mainstream business literature at the start of the 21st century—there can be little doubt that information plays a vital role in the success of any organization. Employees often are required to sign nondisclosure agreements upon entry into an organization wherein they vow that they will not divulge proprietary company information to outsiders. Such safeguards seem reasonable and are becoming necessary for organizations interested in protecting their assets—specifically, their intellectual assets—from getting into the hands of competitors or other entities that could misuse that information. Information is a broad concept, however, and the need for organizations to acquire and subsequently protect information is not limited to patents, “know how,” organizational routines and technologies, and other intellectual property. Organizations also have a need to acquire and protect information about human assets, that is, their employees—the very people who will be entrusted to help the organization succeed. The gathering of employee personal information is dramatically on the rise and the mechanisms through which information is gathered are diverse and controversial.

Organizations have to be careful about how they gather and protect information, because as they attempt to gather personal information through various means, there is the potential to impinge on employees’ sense of information privacy. Information privacy is defined as an employee’s belief in his or her ability to control information about him- or herself and his or her resulting ability to act autonomously—free from the control of others (Stone & Stone, 1990). Information privacy, therefore, reflects an important psychological state influenced jointly by an organization’s need to collect personal information on one hand and an individual employee’s desire to maintain control over his or her personal information on the other hand. This constant tension between the organization and the individual over personal information also suggests that information privacy is part of dialectic process or struggle.

In his 1975 book, The Environment and Social Behavior, Altman argued that privacy represents a boundary-regulation process wherein individuals regulate their interpersonal boundaries with each individual varying in both desire for openness and closedness and ability to reach desired levels of openness and closedness. These needs parallel similar needs in the general psychology literature, including the need for affiliation or belonging and the need for distinctiveness.

There are times in one’s work life, for example, where one wishes to close oneself off from others or to be separate or distinct (e.g., shutting the door to one’s office; not answering phone calls). To the extent that people can achieve their desired level of closedness, privacy is maintained. Similarly, there may be times where the same employee desires social interaction with coworkers—or to be open to others (thus satisfying broader needs for affiliation and belonging). He or she might invite such interaction, for example, by leaving the door open or working in a common area, and to the extent other employees stop by, privacy control is maintained. In this situation, privacy is not threatened because the interaction with others was desired and achieved. If, however, no coworkers stop by to visit when such visits are desired, a privacy void occurs insofar as individuals are experiencing unwanted seclusion. Both psychological goals—desire for openness and desire for closedness—exist along a continuum, and people struggle to achieve an optimum level. Moreover, one’s optimum level may not remain static (i.e., the perceived boundary between the self and others and the desire for openness and closedness are fluid).

Employees are conscious of their own privacy boundaries and the actions of organizations aimed at gathering their personal information. When such organizational aims are irrespective of those boundaries, significant tension can result. That is, the need for an organization to collect employees’ personal information to improve organizational security is frequently in conflict with employees’ desires to maintain control over their personal information. Because of this tension and the growing number of ways—techno-logically and otherwise—organizations are able to monitor employees and collect information about them, the battle for personal information is becoming an increasingly important managerial dilemma that can no longer be easily discounted.

Given this dilemma, a question arises: How much information gathering should managers engage in if increased information gathering may undermine information privacy? To answer this question and understand this dilemma between employee and organization, a clear understanding both of the need for information gathering and the potential damaging effects of invading employee privacy is required. Assisting with this understanding is the primary goal of this research-paper. In this research-paper, significant trends related to information privacy and the concerns of both organizations and employees are discussed. Then, to illustrate the underlying dynamics that create information privacy concerns, a well-publicized case involving a Fortune 500 company, Hewlett-Packard, is introduced. Next, a model of information privacy in the workplace that underscores this managerial dilemma is developed using references to the Hewlett-Packard case. Finally, implications for managers are discussed.

What Organizations Are Doing: Information Gathering And Privacy Trends

Employers must protect their assets, but how far should they intrude into the privacy of their employees in order to accomplish this goal? Employees have rights of privacy, or as Warren and Brandeis (1890) articulate, the right to be let alone, that must be respected, but research also indicates that intrusive electronic and other forms of monitoring might have unintended psychological consequences on employees that can hurt both employees and employers in the long run. In this section, some of the specific trends and emerging technologies that potentially pose privacy threats to employees are discussed.

Electronic Performance Monitoring

Electronic performance monitoring, or EPM, refers to the gathering and processing of information about employees to measure employee performance (Aiello, 1995; Alder, 2001). EPM is commonly used in office settings because the nature of office work increasingly involves the use of computers; EPM can be used to track employee behaviors including keystrokes, Web sites visited, and e-mails created and sent. However, EPM is not limited to computers—it can take place by way of other electronic devices, such as telephones, video monitors, and global positioning systems (GPS). Consider the results from a 2005 American Management Association survey on electronic monitoring:

Web and Internet Monitoring

- 65% of employers block certain Web sites—a 27% increase from 2001

- 76% of employers monitor employee Web surfing

- 26% of employers have fired employees for inappropriate use of the Web or e-mail

- 36% of employers track computer keystrokes

- 50% of employers regularly review total computer con-tent—this is up from 36% in 2001

- 55% of employers retain employee e-mails and review them regularly—this is up from 8% in 2001

Telephone Monitoring

- 57% of employers now block certain lines on their employees’ phones

- 51% of employers now keep track of how long their employees talk on the phone, and about half of these tape and review employee voicemail—this is up from about 12% in 2001

- 6% of employers have fired employees for phone misuse

Video Monitoring

- More than 50% of employers video monitor their employees (up from 33% in 2001)

- 10% of employers video monitor for performance purposes

- 6% videotape all their employees

Global Positioning Systems (GPS) Monitoring

- 8% of employers use GPS to track employee ID cards

- 8% of employers use GPS technology to track employer-owned cars

A burgeoning market of effective and inexpensive technology has made EPM a feasible and readily available tool for most employers.

Personality and Workplace Testing

Workplace testing has become very common in the 21st century (nearly half of employers administer such tests— equating to several million tests each year), and increasingly reliable tests are being developed by researchers to measure individual differences. Workplace tests are often used in the employee selection process to help identify reliable and trustworthy employees who “fit” the organization. Personality tests, for example, are commonly used by employers to help determine whether a potential employee has personality problems or serious emotional disturbances that may adversely affect job performance-related outcomes, and whether the person will fit within the company’s culture. Similarly, integrity tests are often employed to identify potential employees who are likely to engage in theft or other antisocial behavior. Certain organizations, where the confidentiality of information is part of the core business process, have a special interest in hiring people they can trust (i.e., the Central Intelligence Agency [CIA], the National Security Agency [NSA], and financial service companies). These organizations make integrity testing an integral part of their employee-selection process.

Despite their usefulness to organizations, workplace tests are often criticized. Some argue that integrity tests ask questions that probe too far into people’s lives (i.e., aspects that may not affect one’s ability to do the job reliably). Others argue that the administration of such tests is based on the assumption (sometimes false) that corporations have the ability, above and beyond the applicants themselves, to decide which job is best for whom.

Biometrics

Biometric authentication refers to those technologies that are capable of analyzing human biological and other characteristics for identification purposes. Examples include fingerprinting, eye-scanning, and body measurements and the idea behind such measurements is that they, unlike other forms of personal information, are hard to copy or steal. To date, biometrics has not been utilized on a grand scale for workplace purposes, but because of increasingly effective and inexpensive technology, this is likely to eventually change (the market for biometrics grew from $500 million in 2002 to $4 billion in 2007, and continued growth at this rate is anticipated).

The use of biometrics presents privacy concerns because of (a) the fact that biometric information, by its nature, involves the personal characteristics of people who may not want to share in the first place—especially to a government or other agency that may abuse that information in the future, and (b) biometric information could be as potentially susceptible to identity theft as other kinds of identification methods.

Drug Testing

Drug testing is increasing in the work place because most current illicit drug users are employed and drug use by these employees can influence performance and even their safety and the safety of those around them. Because the National Institute on Drug Abuse reports that these employed drug abusers cost their employers twice as much in medical and worker compensation claims as their drug-free coworkers, employers are highly motivated to prevent their employees from using illicit drugs. Common purposes for testing include preemployment testing, random testing, reasonable suspicion testing, post accident or incident testing, and treatment follow-up testing. Types of drug tests commonly required by employers include urine, hair, sweat, and saliva drug screens.

Because drug tests can be intrusive and even embarrassing (urine tests are sometimes conducted while medical personnel observe), a chief concern is that drug tests are too invasive and intruding for the benefit they provide. (Some studies, including the 1994 National Academy of Sciences and the 2004 Independent Inquiry into Drug Testing, have not been able to link drug use other than alcohol with workplace health and safety risks.)

Genetic Testing

Although few employers currently use genetic testing, because of the rapid growth of this science, it’s anticipated that this will change in the near future—especially because the benefits could arguably be to both employees and employers. Genetic testing is the analysis of genes, chromosomes, and proteins in order to predict risk of disease, identify disease carriers, diagnose disease, or determine the likely course of a disease. Genetic testing can be used, for example, to detect genetic abnormalities resulting from workplace exposure to toxins or to detect susceptibility to workplace toxins. Currently, about 900 types of tests can detect about 50 different disorders that impact peoples’ susceptibility to certain workplace toxins.

Genetic testing has obvious potential to aid both employers and employees, but the privacy question arises once again—exactly how much information should an employer have about a particular employee? Should employees have to merely hope that their employers will not opportunistically or negligently abuse their personal information?

“Open Officing,” “Hot Desking,” and “Hotelling”

New technology now allows many employees to work from home or on the go, and as a result, employers have increasingly sought to minimize their expenses for office space while flexibly providing office space for their employees when needed. Different methods of accomplishing this have evolved, most with the intent of supporting a system of unassigned/open, alternating, and/or shared seating arrangements. Intel Corp. and Dell Inc. are examples of large and growing corporations that take advantage of the benefits of “open office.” (At these companies, executives and secretaries often work in identical cubicles next to one another, and oftentimes these employees will share their workspace and/or job with one another in an arrangement referred to as a “two in a box.”)

This openness generally facilitates communication, teamwork, project focus, and employee attitudes, but in addition to these benefits, the sharing of a workspace does have some shortfalls. When executives, teams, or individual employees need to deal with confidential issues, it is difficult if there is no office or room in which they can meet privately. Once again, privacy is an issue.

Wi-Fi And Public Access Computing

Wi-Fi and Public Access Computing refer to the technology that has allowed people to access the Internet in shared locations. Anyone with a Wi-Fi-enabled device such as a computer or a handheld cell phone can connect to the Internet when he or she is near an access point, which covers a certain geographical area ranging from a few square feet to several city blocks. Wi-Fi technology is now often used by people and companies for Internet and phone access, though the technology is expanding to include many kinds of electronic devices.

The benefits of convenience provided by Wi-Fi are obvious, but there are also some potential privacy risks. Specifically, operators of “access points” are often able to access, if they so desire, the computers of those using their access points. This can also work the other way as well—people can hijack access points to gain services that they have not paid for, and they can even damage the access points or computers connected to them. As a result, privacy is at risk.

Summary

Each of the trends just discussed need not necessarily be viewed as undesirable per se, but each trend represents risks—especially the very real risk of compromising information privacy of those affected. Given this risk, one might wonder, are the practices discussed something that only desperate companies do? What about the leading companies? What about a company like Hewlett-Packard?

The Case Of Hewlett-Packard: A Turbulent Recent History

Hewlett-Packard (H-P) was founded in 1939 by William R. Hewlett and David Packard. With 2006 revenues at nearly $92 billion, H-P is regarded as one of the world leaders in the highly competitive and turbulent information technology (IT) industry. With a large footprint in areas such as printers, personal computers, enterprise servers, and cameras, H-P is one of the historical “darlings” of Silicon Valley and is firmly entrenched in the Fortune 100.

In 1999, H-P hired a Lucent Technologies’ executive, Carly Fiorina, as its chief executive officer. Interestingly, it was also in 1999 when the U.S. Congress enacted legislation making it a crime to use pretexting (i.e., falsely impersonating someone in order to gain access to information or records about him or her) to obtain financial information—a practice that would later come back to haunt H-P. Notably, the pretexting legislation passed in 1999 did not address the use of pretexting for purposes other than obtaining financial records.

The hiring of an outsider, Fiorina, was a historic one and marked a major shift in H-P’s family-rooted, “promote-from-within” philosophy. Such a change does not always sit well with organizational “old-timers,” and indeed, the hiring of Fiorina created a political climate at H-P that polarized the organization and fueled mistrust. This mistrust was fueled further in 2002 when, under Fiorina’s championing, H-P acquired rival Compaq Computer Corp. in a $19-billion deal. The merger was vehemently opposed by Walter Hewlett, son of cofounder William Hewlett, who waged a controversial proxy fight over the proposed merger, a fight Fiorina eventually won with the support of H-P’s board of directors.

However, support from the board of directors would eventually wear out. Fiorina tendered her resignation to HP on February 8, 2005, under pressure from the board over disagreements in strategy execution. On March 25, 2005, board member Patricia Dunn announced that Mark Hurd had been hired as chief executive officer, with Dunn serving as chair of the board. Neither Dunn nor Hurd knew at the time that this was just the beginning of a climate at H-P that had turned sour—a climate that was characterized by mistrust, breaches of confidentiality, secretive surveillance and monitoring, questionable tactics, further resignations, and legal actions.

Managerial Framework

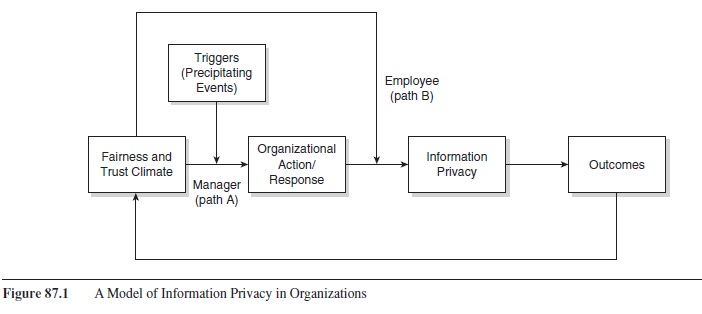

The Hewlett-Packard case study provides a real-world lens through which privacy issues in the workplace can be studied and understood. To that end, a framework will be offered and discussed with the goal of helping managers as they begin to assess the effects of their policies and actions on employee perceptions of information privacy (see Figure 87.1). First, a description of the framework—a general explanatory model for understanding information privacy in the workplace—will be given. Then the framework will be tested by applying it specifically to the Hewlett-Packard case.

Figure 87.1 A Model of Information Privacy in Organizations

Factors Affecting Information Privacy

The key question is—at what point does a company cross the line? That is, when do the actions of an organization, for example, monitoring employees to gather personal information, lead to invasions of privacy (e.g., when people’s actual levels of interaction are higher than their desired levels of interaction) where invasion implies some suboptimal level of information control? Figure 87.1 addresses this question. As can be seen, climate plays a critical dual role in triggering information privacy concerns.

Climate

Climate refers to employees’ perceptions of formal and informal organizational policies and procedures (Ostroff, Kinicki, & Tamkins, 2003), and the climate literature distinguishes between individual perceptions (i.e., psychological climate) and group or aggregate perceptions (i.e., organizational climate). Climate reflects the current “pulse” of the organization—how it feels overall at a particular time. When there is shared agreement among organizational members, a strong organizational climate exists. Management scholars have studied different types of climate including safety climate, justice climate, and climate for change.

The first author of this research-paper (along with his colleagues Jerald Greenberg and Chad Brinsfield), has elsewhere argued that justice climate plays a particularly powerful role in shaping people’s reactions to organizational attempts to gather information (Alge, Greenberg, & Brinsfield, 2006). On the one hand, it acts as a driver—determining the types of organizational information-gathering practices that are deemed necessary—that is, climate can affect organizational decision makers’ perceived need for personal information, prompting them to enact monitoring and related practices (path A in Figure 87.1). On the other hand, climate provides information to employees as they try to assess the impact of their organizations’ efforts to gather their personal information (path B in Figure 87.1).

Early research on justice climate focused on procedural justice climate—the climate associated with the fairness of procedures an organization uses in reaching its decisions about employees. However, justice climate can also encompass interpersonal justice—the extent organizations treat its employees with dignity and respect, and informational justice—the extent organizations provide information and explanations for decisions. For our purposes, justice climate refers to the total justice climate including procedural, interpersonal, and informational components.

Triggers

In addition to organizational climate, critical events in the immediate time period may further fuel organizational decisions—that is, fuel the perceived need to collect more information—prompting the organization to increase the intensity and breadth of its information-gathering practices. For example, organizations may feel vulnerable to sexual harassment lawsuits (prompted by an employee complaining about a coworker sending inappropriate e-mail messages), and consequently, this vulnerability drives or increases the perceived need to more diligently gather personal information to control the actions of employees.

Organizational Action/Response

Organizational actions and responses refer to the information-gathering practices that organizations enact, including electronic monitoring and personality testing. When organizations have strongly positive justice climates, managers will be less likely to initiate and sustain information-gathering efforts. Under such circumstances, the perceived need for information is lower, and managers are consequently willing to live without the additional personal information. That is, there is trust.

When trust exists, there is less need for external control mechanisms such as monitoring. Trust, therefore, is an alternative or substitute for formal controls. When trust is high, organizations are willing to take on greater risk—that is, they are willing to be vulnerable to the possibility that employees will behave opportunistically. In essence, when trust is high, organizations are more likely to “bet” that their members will behave in a manner consistent with organizational goals.

When trust is low, however, managers have little confidence that employees will behave in the organization’s interests. Such is typically the case when the justice climate is poor. Research has shown a consistently strong conceptual and empirical relationship between fairness in organizations and organizational trust (De Cremer, van Dijke, & Bos, 2006; Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, 1995). Lacking trust, therefore, managers are more likely to implement external controls. They might, for example, gather information on employee performance via electronic monitoring by tracking employee movements (with GPS or video cameras), monitoring Web usage, or reviewing e-mail. They might turn to nonelectronic measures such as hiring private investigators to document the behaviors of employees or incorporate indirect measures of behavior such as personality tests. The very nature of these actions threatens information privacy because these actions require the collection of personal information, which may be at odds with an employee’s willingness to give that information. Trust matters in information exchanges where privacy is a concern and fairness climate helps inform trust. When fairness and trust climate is poor, organizations will increase personal information collection efforts to substitute control for lack of trust.

Information Privacy

Increased organizational actions to gather personal information pose a threat to employees’ perceptions of information privacy—employees will feel less in control of their personal information, thereby experiencing an invasion of privacy. These effects are likely to be particularly severe when the actions take place in a climate that employees deem to be unfair and untrustworthy. At the same time, information-gathering efforts by organizations that are conducted within a fair climate may have little or no negative impact on information privacy concerns. For example, research indicates that when fairness principles are adhered to—for example, by providing advance notice with a detailed, sincere explanation for the organization’s intention to monitor—employee reactions will be less severe.

At this point, a practical question arises—why should organizations care? Is there a compelling business case for minimizing information privacy violations? In other words, can minimizing privacy violations help performance-related outcomes? The next section helps us answer this question.

Outcomes of Information Privacy

The ability to achieve an optimal level of information privacy is essential to one’s psychological well-being. In his seminal 1967 book, Privacy and Freedom, Alan Westin describes four key psychological functions that privacy serves: autonomy, emotional release, self-evaluation, and limited and protected communication.

On autonomy Westin notes, “the individual’s sense that it is he who decides when to ‘go public’ is a crucial aspect of his feeling of autonomy” (p. 34). Emotional release, having opportunities to express oneself without the critical evaluative eye of an audience, is an important component in Newell’s (1994) privacy conceptualization wherein privacy is critical to human-system maintenance and well-being. The notions of cognitive relief, catharsis, and rejuvenation (Pedersen, 1997), similarly reflect Westin’s view of emotional release. Self-evaluation refers to the opportunity for individuals to reflect and process information. Finally, Westin’s (1967) function of limited and protected communication ensures opportunities to share information with trusted others, and establishes boundaries regarding what can be revealed to others. Although each of these functions of privacy may in and of themselves drive particular employee behaviors, collectively they suggest that when employees’ privacy is maintained, their intrinsic motivation ought to be salient. To illustrate the psychological and behavioral manifestations of this increased intrinsic salience, the primary focus will be on autonomy.

The autonomy function of privacy is important to a number of important employee outcomes. First, autonomy contributes to an overall sense of psychological empowerment (Spreitzer, 1995). Second, in part because of increased empowerment, autonomy enhances creativity (Amabile, 1983, 1988). Indeed, recent research has found employees’ information privacy perceptions are positively associated with increased feelings of psychological empowerment and with increases in organizational citizenship behavior and creativity (Alge, Ballinger, Tangirala, & Oakley, 2006; Amabile, 1983, 1988; Zhou, 2003). Thus, maintaining in-formation privacy tends to enhance employees’ intrinsic motivation—increasing their sense of psychological empowerment and consequently, their creative performance on the job and their willingness to go above and beyond the call of duty—behaviors that tend to increase individual contributions to the overall competitiveness and performance of the organization.

On the other hand, when information privacy is impinged and employee intrinsic motivation is undermined, a reactance response is triggered that causes individuals to seek to reestablish control. Unfortunately for the organization, this may take the form of increased employee deviance behaviors such as leaking company information, theft, and sabotage, which are behaviors that tend to decrease performance outcomes.

So, in answer to the previously raised question—why should organizations care about information privacy—organizations should indeed care, because information privacy issues are likely to impact important psychological and behavioral outcomes of employees, which can in turn impact performance-related outcomes.

Information Privacy and Hewlett-Packard

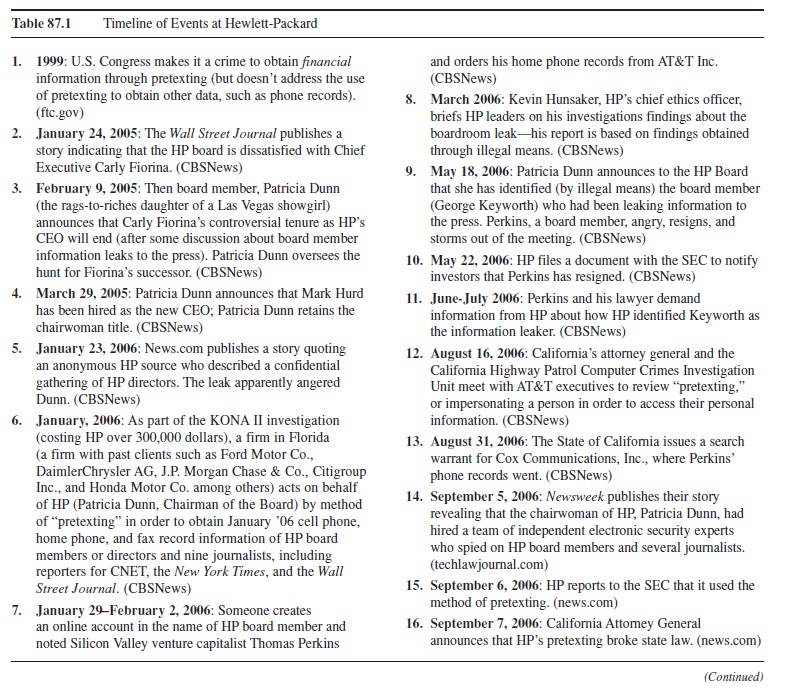

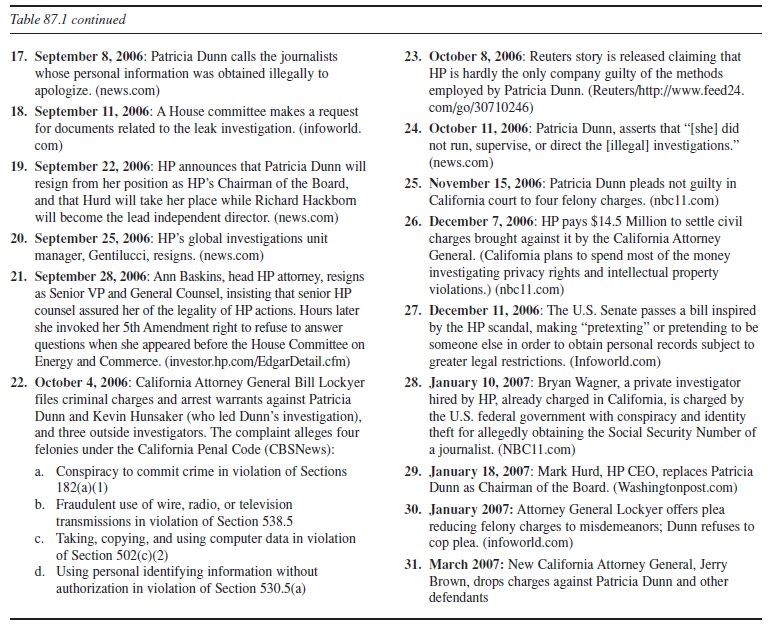

This section will focus on the application of the foregoing principles and model to the Hewlett-Packard case (see Table 87.1 for timeline of events at H-P).

Organizational Actions and Fallout

On October 4, 2006, California Attorney General Bill Lockyer filed criminal charges against H-P chairwoman of the board, Dunn, H-P attorney, Kevin Hunsaker, and three outside investigators. Dunn, who resigned from her position as H-P’s chairwoman in September of 2006, orchestrated surveillance against H-P board members—surveillance that used a controversial practice known as pretexting wherein investigators posed as H-P board members and as journalists to obtain their confidential personal phone records.

Thus, the critical organizational action in the H-P case that could affect employee-information privacy perceptions was the collection of personal information using nefarious means—specifically pretexting.

Allegedly, these surveillance activities violated several sections in the California Penal Code and consequently led the filing of four felony charges: (a) conspiracy to commit a crime; (b) fraudulent use of wire, radio, or television transmissions; (c) taking, copying, and using computer data in violation of Section 502(c)(2); and (d) using personal identifying information without authorization. Al-though federal law gives employers much leeway in how it chooses to monitor its employees, each state can impose additional privacy or monitoring stipulations. California is one of the strictest states in this regard and, unlike many states, explicitly recognizes a right to privacy in its state constitution.

Table 87.1 Timeline of Events at Hewlett-Packard

- 1999: U.S. Congress makes it a crime to obtain financial information through pretexting (but doesn’t address the use of pretexting to obtain other data, such as phone records). (ftc.gov)

- January 24, 2005: The Wall Street Journal publishes a story indicating that the HP board is dissatisfied with Chief Executive Carly Fiorina. (CBSNews)

- February 9, 2005: Then board member, Patricia Dunn (the rags-to-riches daughter of a Las Vegas showgirl) announces that Carly Fiorina’s controversial tenure as HP’s CEO will end (after some discussion about board member information leaks to the press). Patricia Dunn oversees the hunt for Fiorina’s successor. (CBSNews)

- March 29, 2005: Patricia Dunn announces that Mark Hurd has been hired as the new CEO; Patricia Dunn retains the chairwoman title. (CBSNews)

- January 23, 2006: News.com publishes a story quoting an anonymous HP source who described a confidential gathering of HP directors. The leak apparently angered Dunn. (CBSNews)

- January, 2006: As part of the KONA II investigation (costing HP over 300,000 dollars), a firm in Florida (a firm with past clients such as Ford Motor Co., DaimlerChrysler AG, J.P. Morgan Chase & Co., Citigroup Inc., and Honda Motor Co. among others) acts on behalf of HP (Patricia Dunn, Chairman of the Board) by method of “pretexting” in order to obtain January ’06 cell phone, home phone, and fax record information of HP board members or directors and nine journalists, including reporters for CNET, the New York Times, and the Wall Street Journal. (CBSNews)

- January 29-February 2, 2006: Someone creates an online account in the name of HP board member and noted Silicon Valley venture capitalist Thomas Perkins and orders his home phone records from AT&T Inc. (CBSNews)

- March 2006: Kevin Hunsaker, HP’s chief ethics officer, briefs HP leaders on his investigations findings about the boardroom leak—his report is based on findings obtained through illegal means. (CBSNews)

- May 18, 2006: Patricia Dunn announces to the HP Board that she has identified (by illegal means) the board member (George Keyworth) who had been leaking information to the press. Perkins, a board member, angry, resigns, and storms out of the meeting. (CBSNews)

- May 22, 2006: HP files a document with the SEC to notify investors that Perkins has resigned. (CBSNews)

- June-July 2006: Perkins and his lawyer demand information from HP about how HP identified Keyworth as the information leaker. (CBSNews)

- August 16, 2006: California’s attorney general and the California Highway Patrol Computer Crimes Investigation Unit meet with AT&T executives to review “pretexting,” or impersonating a person in order to access their personal information. (CBSNews)

- August 31, 2006: The State of California issues a search warrant for Cox Communications, Inc., where Perkins’ phone records went. (CBSNews)

- September 5, 2006: Newsweek publishes their story revealing that the chairwoman of HP, Patricia Dunn, had hired a team of independent electronic security experts who spied on HP board members and several journalists. (techlawjournal.com)

- September 6, 2006: HP reports to the SEC that it used the method of pretexting. (news.com)

- September 7, 2006: California Attorney General announces that HP’s pretexting broke state law. (news.com)

- september 8, 2006: Patricia Dunn calls the journalists whose personal information was obtained illegally to apologize. (news.com)

- september 11, 2006: A House committee makes a request for documents related to the leak investigation. (infoworld. com)

- september 22, 2006: HP announces that Patricia Dunn will resign from her position as HP’s Chairman of the Board, and that Hurd will take her place while Richard Hackborn will become the lead independent director. (news.com)

- september 25, 2006: HP’s global investigations unit manager, Gentilucci, resigns. (news.com)

- september 28, 2006: Ann Baskins, head HP attorney, resigns as Senior VP and General Counsel, insisting that senior HP counsel assured her of the legality of HP actions. Hours later she invoked her 5th Amendment right to refuse to answer questions when she appeared before the House Committee on Energy and Commerce. (investor.hp.com/EdgarDetail.cfm)

- october 4, 2006: California Attorney General Bill Lockyer files criminal charges and arrest warrants against Patricia Dunn and Kevin Hunsaker (who led Dunn’s investigation), and three outside investigators. The complaint alleges four felonies under the California Penal Code (CBSNews):

- Conspiracy to commit crime in violation of Sections 182(a)(1)

- Fraudulent use of wire, radio, or television transmissions in violation of Section 538.5

- Taking, copying, and using computer data in violation of Section 502(c)(2)

- Using personal identifying information without authorization in violation of Section 530.5(a)

- october 8, 2006: Reuters story is released claiming that HP is hardly the only company guilty of the methods employed by Patricia Dunn. (Reuters/http://www.feed24. com/go/30710246)

- October 11, 2006: Patricia Dunn, asserts that “[she] did not run, supervise, or direct the [illegal] investigations.” (news.com)

- November 15, 2006: Patricia Dunn pleads not guilty in California court to four felony charges. (nbc11.com)

- December 7, 2006: HP pays $14.5 Million to settle civil charges brought against it by the California Attorney General. (California plans to spend most of the money investigating privacy rights and intellectual property violations.) (nbc11.com)

- December 11, 2006: The U.S. Senate passes a bill inspired by the HP scandal, making “pretexting” or pretending to be someone else in order to obtain personal records subject to greater legal restrictions. (Infoworld.com)

- January 10, 2007: Bryan Wagner, a private investigator hired by HP, already charged in California, is charged by the U.S. federal government with conspiracy and identity theft for allegedly obtaining the Social Security Number of a journalist. (NBC11.com)

- January 18, 2007: Mark Hurd, HP CEO, replaces Patricia Dunn as Chairman of the Board. (Washingtonpost.com)

- January 2007: Attorney General Lockyer offers plea reducing felony charges to misdemeanors; Dunn refuses to cop plea. (infoworld.com)

- March 2007: New California Attorney General, Jerry Brown, drops charges against Patricia Dunn and other defendants

Privacy will likely be salient in this situation for several reasons. First, the mere collection of personal information increases privacy tensions. Second, in evaluating information privacy, employees seek understanding and in particular look to the “legitimacy” of the information gathering and handling practices (Alge et al., 2006). The fact that H-P’s actions were not only questionable ethically, but also may have broken federal and state laws, raises serious questions concerning legitimacy. The stakeholders affected (in this case, the board members who were spied on) were not informed of the potential of surveillance in advance. Moreover, deception was used to collect their personal phone records and to do so, private investigators fraudulently misrepresented themselves as board members to phone companies using board members’ social security numbers. Finally, actions taken in this manner undermine any trust that may have existed. Consequently, board members and employees will lack confidence that their personal information will be respected and safeguarded. Hence, they will feel they have less control over their personal information.

So given this, why would H-P revert to pretexting methods to spy on its board of directors?

Climate and Precipitating Triggers

What factors led Dunn to spy on her own fellow board members at H-P? To begin, the climate at H-P had begun to sour during Fiorina’s tenure. In particular, the Compaq merger appeared to be a particularly polarizing event, pitting Fiorina and her board against H-P old-timers. In the proxy fight, accusations and misinformation were spread, contributing to a general environment of mistrust. In addition, Fiorina was battling damaging proprietary, confidential information leaks to the press that only board members would know (Markoff, 2006). The polarization from the Compaq merger, the damaging leaks of information to outsiders, and a CEO, Fiorina, who was an “outsider” as well, all created an environment of mistrust that would contribute greatly to Chairwoman Dunn’s later decision to use pretexting to spy on her board members.

After Fiorina was forced out at H-P, top-secret information was again leaked to various media outlets, including the technology news site CNET.com. These leaks would constitute precipitating events—events that are particularly salient and important to the decision to gather more personal information (see Figure 87.1). The leaks put H-P and Dunn in a vulnerable position—increasing their need to gather more personal information to root out any “squeaky wheels.” Certainly, the goal of eliminating harmful leaks seemed worthwhile for Dunn. Thus, a poor justice and trust climate created a need to monitor and control, and this need was accelerated by the security breaches of unknown, suspected board members who may have leaked confidential information to the press.

Information Privacy

The fact that H-P was using pretexting to gather the personal phone records of its board members was insufficient to trigger information privacy concerns. That is, one must have knowledge that his or her personal information is vulnerable to outside control, that is, no longer under his or her sole personal control.

When Dunn received a report from the spying she had ordered, she called a meeting of the board. There she announced that board member George Keyworth was the source of the leaks. Keyworth was dismissed from the board, but another board member, Thomas Perkins, who objected to the methods used, also resigned from the board, and it was not until September of 2006 that the controversial use of pretexting was made public. H-P was required to report to the SEC of board changes. This, coupled with pressure from Perkins, led to the September 2006 disclosure from H-P of the pretexting effort. A firestorm of criticism and scrutiny ensued, and the very public nature of H-P’s spy activity made salient the risk that organizational members faced.

Outcomes

Immediate outcomes in the H-P case were both voluntary (e.g., Perkins) and involuntary (Dunn, Keyworth) departures. However, what might be the other short-term and long-term outcomes from the H-P scandal? Do actions like these, coupled with the already poor climate suggest that information privacy will continue to be a concern at H-P? If so, perhaps employees of H-P will feel less in control and experience less intrinsic motivation to perform in the future. This may manifest itself in decreased creativity, employee silence or withholding of information, greater impression management, fewer helping behaviors, and an increase in some types of employee deviance, namely deviance that is difficult for monitoring and surveillance to detect. Though it may be difficult to validate whether any of these concerns come to fruition at H-P post surveillance, one thing is clear: H-P suffered a significant blow to its image and this could affect future public relations, image, customer and employee loyalty, and H-P’s ability to attract talent.

Managerial Implication

This research-paper illustrates the complex nature of information privacy in organizations. Twenty-first-century managers face many difficult choices when it comes to collecting and handling employee information. Managers must ask themselves the following questions:

- Should I collect personal information at all? Is there a compelling need?

- What specific information should be collected?

- How much information should be collected?

- How often should information be collected?

- What are the means through which information will be collected? Are the procedures fair?

- For what purpose will the information be collected? That is, how will it be used? Is there proper justification? Is that justification clearly shared with employees before the collection occurs?

- What is the climate like? Is it conducive to collecting personal information?

Managers must be prepared to address these questions prior to any organizational actions targeted to acquire and use employee personal information. That is, managers must pay attention to the design of the systems (the technologies, people, and processes) responsible for the collection and use of employee personal information. Fairness should be a primary concern. Specifically,

- managers must be sure that the climate is sufficiently benign so that people’s reactions to personal information gathering will be inconsequential. If the climate is not sufficiently benign, then managers ought to first consider improving the fairness climate before moving to actions to gather personal information. (In fact, improving the climate may mitigate the need to collect such information.)

- once the decision has been made to collect personal information, managers must make sure due process is adhered to—they should involve employees in the design of such systems, provide advanced notice of information gathering, ensure employees authorize any external use of collected data, and provide a detailed explanation for why such information is necessary for them to collect, thereby increasing employee understanding and acceptance. By making the process transparent to employees, employees will retain some measure of control over their personal information— alleviating the threat to information privacy.

Conclusions

Information privacy continues to be a concern as organizations increasingly collect and handle employee personal information. Presumably, the ultimate goal of these efforts is to ensure competitive viability and survival of the organization. At the same time, these efforts can have the

paradoxical effect of actually making organizations less competitive, particularly if information privacy is not maintained. For example, and as discussed, information privacy is inextricably linked to intrinsic motivation, and employees whose privacy is threatened will be less motivated to share knowledge, take risks, and provide the types of creative input that will ensure an organization remains competitive.

With respect to H-P, the verdict is still out. In January 2007, then Attorney General Lockyer offered to reduce the felony charges to misdemeanors in a plea arrangement. Dunn and the others accused refused to cop a plea—presumably because they could have still been under jeopardy at the federal level. In March of 2007, however, the new attorney general Jerry Brown dropped all charges against Dunn and the others. Thus, even in a state like California, where workplace privacy is given more credence, it is often difficult to prosecute organizations for spying activities that threaten employee privacy, as the H-P case illustrates. It remains to be seen whether federal charges will be brought against the participants in the H-P pretexting case.

Though it is hard to perceive all possible and future ramifications, one thing is for sure with respect to the HP scandal: the actions taken by Dunn have been felt both internally by H-P stakeholders and externally in the form of negative publicity. So, returning to one of the initial questions raised in this research-paper—can organizations go too far with respect to gathering information on its employees? The H-P case suggests that answer is a resounding “yes.”

Aside from the public-relations problems that the H-P case presents, what does it mean strategically for H-P? That is, how might innovation in the long-term be affected? The model presented in this research-paper points to the constraining effect of information gathering on innovation and subsequent performance-related outcomes. Yet, companies like H-P supposedly have made their mark on innovation. Interestingly, in her recent book, Tough Choices, former H-P CEO Fiorina is a bit more critical of the innovative culture. She writes about H-P and its founders:

Bill and Dave had once been radicals and pioneers. Now, I’d seen too many instances where a new idea was quickly dismissed with the comment: “We don’t do it that way. It’s not the HP Way.” The HP Way was being used as a shield against change.

Could Fiorina’s insight foreshadow things to come? It’s inarguably true that the leaks, the mistrust, and the secret surveillance may all work to create a climate that makes innovation difficult—innovation that H-P has supposedly built its reputation around. It will be interesting to see how things unfold.

References:

- Aiello, J. R. (1995). Electronic performance monitoring and social context: Impact on productivity and stress. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80(6), 738-745.

- Alder, G. S. (2001). Employee reactions to electronic performance monitoring: A consequence of organizational culture. Journal of High Technology Management Research, 12(2), 323-342.

- Alge, B. J. (2001). Effects of computer surveillance on perceptions of privacy and procedural justice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(4), 797-804.

- Alge, B. J., Ballinger, G. A., Tangirala, S., & Oakley, J. L. (2006). Information privacy in organizations: Empowering creative and extra-role performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(1), 221-232.

- Alge, B. J., Greenberg, J., & Brinsfield, C. (2006). An identity-based model of organizational monitoring: Integrating information privacy and organizational justice. In J. Martocchio (Ed.), Research in personnel and human resource management, (Vol.25, 71-135). San Diego, CA: Elsevier.

- Altman, I. (1975). The environment and social behavior: Privacy, personal space, territory, crowding. Monterey, CA: Brooks/ Cole Publishing.

- Amabile, T. M. (1983). The social psychology of creativity: A componential conceptualization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(2), 357-377.

- Amabile, T. M. (1988). From individual creativity to organizational innovation. In K. Gronhaug & G. Kaufmann, G. (Eds.), Innovation: A cross-disciplinary perspective (pp. 139-166). New York: Oxford.

- Amabile, T. M. (1997). Motivating creativity in organizations: On doing what you love and loving what you do. California Management Review, 40(1), 39-58.

- American Management Association. (2005). Electronic monitoring and surveillance survey. New York: Author.

- American Management Association. (2007). American Management Association (AMA) management training and professional development seminars, workshops and books. Retrieved September 2, 2007, from http://www.amanet.org/

- Bernstein, J. (1999, April 22). Financial identity theft. Federal Trade Commission. Retrieved September 3, 2007 from http:// www.ftc.gov/os/1999/04/identitythefttestimony.htm

- Carney, D. (2006, September 6). HP admits spying on its directors via pretexting to obtain confidential home phone records. Tech Law Journal. Retrieved September 3, 2007, from http:// www.techlawjournal.com/topstories/2006/20060906.asp

- CBS News. (2006, October 4). Paper jam at HP. Retrieved September 3, 2007, from http://www.cbsnews.com/elements/ 2006/10/04/in_depth_business/timeline2063653.shtml

- Culnan, M. J., & Armstrong, P. K. (1999). Information privacy concerns, procedural fairness, and impersonal trust: An empirical investigation. Organization Science, 10(1), 104-115.

- De Cremer, D., van Dijke, M., & Bos, A. E. R. (2006). Leader’s procedural justice affecting identification and trust. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 27(7), 554-565.

- Electronic Privacy Information Center. (2007). Electronic Privacy Information Center home page. Retrieved September 3, 2007, from http://www.epic.org/

- Fiorina, C. (2006). Tough choices. New York: Penguin.

- Gross, G. (2006, December 11). Congress passes ‘pretexting’ phone records bill. InfoWorld. Retrieved September 2, 2007, from http://www.infoworld.com/article/06/12/11/ HNcongresspretextingbill_1.html

- Kawamoto, D., & Krazit, T. (2006, September 5). Media leaks prompt HP board shake-up. Cnet News. Retrieved September 2, 2007, from http://news.com.com/2100-1014_3-6112501.html

- Markoff, J. (2006, October 5). Ex-chief of H.P. pursued leaks, too. The New York Times. Retrieved August 28, 2007, from http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/05/technology/05leak .html?ex=1188446400&en=5080f1917aba2468&ei=5070

- Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, (20)3, 709-734.

- Mullins, R. (2007, January 18). California offers Dunn, former HP execs, plea deals. InfoWorld. Retrieved September 3, 2007, from http://www.infoworld.com/ archives/emailPrint.jsp?R=printThis&A=/article/07/01/18/ HNhpexecpleadealoffer_1.html

- National Workrights Institute. (2007). National Workrights Institute home page. Retrieved September 2, 2007, from http:// www.workrights.org/

- Newell, P. B. (1994). A systems model of privacy. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 14(1), 65-78.

- Ostroff, C., Kinicki, A. J., & Tamkins, M. (2003). Organizational culture and climate. In W. C. Borman, D. R. Ilgen & R. J. Klimoski (Eds), Handbook of psychology, (Vol. 12, pp. 565593). New York: Wiley.

- Pedersen, D. M. (1997). Psychological functions of privacy. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 17(2), 147-156.

- Privacy Rights Clearinghouse. (2007). Privacy Rights Clearinghouse. Retrieved September 2, 2007, from http://www.pri vacyrights.org/

- Richtel, M. (2007, March 15). Charges dismissed in Hewlett-Packard spying case. New York Times. Retrieved September 2, 2007, from http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/15/technology/ 15dunn.html?ex=1331611200&en=db679c65c6af7740&ei= 5089&partner=rssyahoo&emc=rss

- Robertson, J. (2007, January 11). Investigator faces charges in HP probe. Washington Post. Retrieved September 2, 2007, from http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/ article/2007/01/11/AR2007011100075.html

- Shankland, S. (2006, September 8). HP chairman: Use of pretexting ’embarrassing’. Cnet News. Retrieved September 2, 2007, from http://news.com.com/HP+chairman+Use+of+pr etexting+embarrassing/2100-1014_3-6113715.html

- Spreitzer, G. M. (1995). Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 38(5), 1442-1465.

- Stanton, J. M., & Stam, K. R. (2006). The visible employee. Med-ford, NJ: Information Today.

- Stone, E. F., & Stone, D. L. (1990). Privacy in organizations: Theoretical issues, research findings, and protection mechanisms. In G. Ferris & K. Rowland (Eds.), Research in personnel and human resource management (Vol. 8, pp. 349-411). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

- Warren, S., & Brandeis, L. D. (1890). The right to privacy. Harvard Law Review, 4, 193-200.

- Westin, A. F. (1967). Privacy and freedom. New York: Atheneum.

- Zhou, J. (2003). When the presence of creative coworkers is related to creativity: Role of supervisor close monitoring, developmental feedback, and creative personality. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(3), 413-422.

- Zuboff, S. (1988). In the age of the smart machine: The future of work and power. New York: Basic Books.

- Zweig, D., & Webster, J. (2002). Where is the line between benign and invasive? An examination of psychological barriers to the acceptance of awareness monitoring systems. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(5), 605-633.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.