This sample Organizational Change Agency Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Most academic disciplines are marked by their employment of essential concepts; that is, the way that their own theories, ideas, and constructs are used to capture or provide knowledge about particular phenomena. While there is some debate about the issue, it seems at least viable that change has become one of those essential concepts for the field of organizational development (e.g., Caldwell, 2005b).

Indeed, if there were a concept that would rival any other in the past 2 decades of discourse about organizational dynamics, it would be change. So pressing the perceived need, and so acute the perceived circumstances, that just a few years ago the periodical Fast Company featured the headline “Change or Die!” on the cover.

For the most part, the headline is true. Change has become an integral part of organizational life for both organizational members and organizations. Increasingly powerful technology plays some of a role in this: Technology advances now almost as fast as it processes information, so the ability to process more information faster requires new, innovative ways of managing information for better decisions. These new innovative ways of managing, in turn, set up an internal organizational dynamic of constant change. It is common—even trite by now—to hear members of all types of organizations talk about a current change initiative as the flavor of the month. While workers (and managers) may be a bit jaded by all of the change and all of the talk about change, it does make the process of change agency in the 21st century a rather complex phenomenon.

Change agency refers to how change is actually accomplished in organizational life. For every organizational change, some mechanism or entity has instigated it or is responsible for the guidance, implementation, or maintenance of the change. This mechanism or entity—usually a human being—is called a change agent. The activity of this mechanism or entity is called change agency.

In this research-paper, I sketch a picture of change agency in 21st-century organizational life. My broad purpose is twofold: (a) to provide a more or less comprehensive understanding of the nature and functions of change agency in organizations—the nature and function of agency changes, certainly, according to organizational structure, culture, and the type of the change initiated; and (b) to offer some potential avenues of agency for readers inclined to take up the actual work of organizational change. While much of the change work is conceived and initiated in the context of organizational development (OD) by OD professionals, much of it also could and should be undertaken by professionals in other organizational roles.

Specifically and by way of preview, in this research-paper, I (a) define change and agency; (b) provide a brief history of change agency in organizational life; (c) illustrate/schematize the nature, scope, and function of change agency in terms of the “political” intent and direction of the change; and (d) characterize the role of six different possibilities of change agent.

Organizational Change And Agency

As implied from the introductory discussion, there can be little if any productive discussion of change agency without an understanding of the nature of organizational change itself. Change and agency are therefore reciprocally defined.

Organizational Change

Perhaps the most discussed phenomenon in the area of organizational dynamics and development for the last 20 years, organizational change refers to a perplexing myriad of phenomena, activities, initiatives, and campaigns in organizations that have one thing in common: movement of some sort from one set of thoughts or behaviors to another set of thoughts or behaviors.

This movement can be distinguished in terms of scale or size and magnitude or comprehensiveness. It can involve the entire organization, or a subsystem (department or functional unit) of an organization. It can seek to transform the entire organization, as in an organization moving from a traditional authoritative hierarchy to a participative, flatter structure or moving into unfamiliar markets with a new strategy; or it may seek incremental changes, as in an organization retooling for the latest technology-assisted production, introducing new employee personnel forms, or new ways for teachers to record grades. Change can also be remedial—seek to correct small problems—or developmental—rethink the way some things are done so that the same problems do not recur.

It may be also be productive to distinguish change from other concepts and terms that are associated with change and sometimes used as synonyms.

Change

A most simple definition, but one that is also comprehensive might be movement from one comparatively, temporally stable state to another temporally stable state.

Organizational change occurs with those situations in which performance of job functions require most people throughout the organization to learn new behaviors and skills. Major change encompasses an entire workforce and can focus on innovation and skill development of people (Data Warehouse Glossary, n.d.).

Note that the new learned behaviors and skills are expected to be comparatively stable, at least for a while.

Learning

According to Chris Argyris, learning can be in one of two forms: (a) error correction or (b) examination of the thinking that produced the error in the first place. The first is called single-loop learning. The second is called doubleloop learning and more closely resembles change as used in this research-paper.

Innovation

Innovation is a term usually reserved for new products or services with remarkable improvements over previous products or services. An “innovative” product or service is one likely to be dramatically different in design, delivery, or effect upon consumer, a difference that results from thinking about the product or service in ways not anticipated by the status quo or current way of thinking. For example, bar codes on products is/was innovative in that it eliminated the needs for price tags, pricing guns, pricers, and cashiers to read price tags; the advent of the digital camera is innovative because it does not use film; online banking is innovative because it does not require trips to the bank and personal transactions with bank tellers; some K-6 educational software is innovative because it teaches children to think and solve problems holistically and collaboratively to sustain the planet for good test grades rather than linearly and individually. Consumer products without prices, photography without film, banking without banks, and education without tests can certainly be considered innovative.

Development

Development is a term usually used to indicate measurable progress toward a stipulated, desired goal and usually reserved for individuals, groups, and organizations to indicate the state of progress, preparation, or readiness for goal achievement.

Change Agent, Change Agency

It is also important to distinguish between the agent of change, and the source or cause of change. The latter is attributable to a perceived or felt “discrepancy” between where the organization is and where it wants to be. This discrepancy can be perceived or felt by anyone in the organization but usually comes from those who are able to have a sense of “what could be” or “what needs to be,” relative to “what is.” Four primary areas in which this discrepancy can be felt are

- strategy, as in the suspicion that the current strategy is not working, or that a different one may be more productive for the future;

- technology, as in the suspicion that an organization’s current IT system is not providing information as fast or as comprehensively as it should;

- organizational structure, as in the suspicion that informed participation by lower line supervisors may enhance decision making at the managerial level; and

- people, as in the suspicion that lower line supervisors possess neither the confidence or competence to participate in managerial decision making.

A change agent or agent of change, by contrast, is one whose intentional actions initiate, facilitate, or otherwise cause the desired change to be accomplished—a movement from one set of thoughts or behaviors to another on the part of a larger group such as an organization or society. In the contemporary organization, a change agent is typically associated with a change in the organization’s culture.

Change agency may be thought of as the mechanism or means by which change is accomplished. It may refer to the those intentional actions—in whole or in part—on the part of an agent, or it may refer to abstract phenomena or circumstances external to the organization (e.g., new city ordinances that allow/disallow the sale of alcohol sales for eating establishments, new zoning regulations that prevent emissions from manufacturing plants during certain hours, or the demise of a competitor). In these cases, we can say that change has happened, but the mechanism through which change is accomplished is complex and nebulous, and not fruitfully traceable to a particular agent or agency. More often than not, however, a change agent will be a human being, and change agency will refer to the actions of this human being.

The Short History Of Organizational Change Agency

It may be surprising, but despite all that has been written about organizational change and change agency, a detailed history of the concept and/or the practice is not among those readings.

Kleiner’s (1996) The Age of Heretics stands out as perhaps the most valuable account of the practice of organizational change and the agents engaged in those practices. Located precisely at the site of mid-20th-century counter culture, Kleiner attributed the contemporary origins of the practice of organizational change agency to the decades 1950-1970, where change agency constituted heresy in the long-established traditions of managerial and bureaucratic corporate control. Indeed, much of what constitutes change agency today derives from those “heretics, heroes, and outlaws” who saw human spirit withering at work and sought means to resurrect it against mainstream corporate concerns and fiduciary values.

Although there are no academic histories of change agency that correspond to Kleiner’s (1996) chronology of the practices of the original renegade change agents, intellectual histories can be pieced together from predominant strands of intellectual thinking at various periods in the past 60 years or so. Caldwell’s (2005a) account may be considered as a noteworthy effort, in that he classified intellectual thinking about change and change agency into four essential discourses:

- Rationalist discourses are built on modernist premises of the rationality and logic of science and on the hope that it will provide a stable, orderly, predictable world. Rationalist discourses employ a notion of a central, expert change agent, one who knows—or one who assumes he or she knows—what needs to be done and how to do it and who presumes that changes imposed upon the unsuspecting are fine as they are for their own good or for the ultimate good of the organization.

- Contextualist discourses understand organizational change not in terms of an objective set of standards or invariant rationality, but as a naturally occurring product of management situations—that is, change is always understood in a context. Moreover, the context itself, much like each management decision-making situation, is dynamic and changing. Consequently, change is understood as emergent, and agency is understood as “doing what we can with what we have/know” or as “in context.”

- Dispersalist discourses employ more contemporary and familiar concepts such as “team or “learning community” as the focus of change or agency. Here, the “expertise” of change and the power to conduct it are “dispersed” to management teams, rather than appropriated by executive level leaders. Such “dispersal” is coincident with empowerment and participation initiatives, and particularly popular in the 1990s downsizing movement.

- Constructionist discourses (all but) remove agency from the process of change. Relying on a postmodern set of philosophical assumptions, constructionist discourses tend to suggest that nothing really exists apart from our “constructions” of them through communication. Consequently, con-structionist discourses view change as a permanent concept placed on an always impermanent dynamic, thus always subject to change via communication. Agency is largely a myth for the constructionist, as it would assume the stability of phenomena to change as well as the intentionality of the change agent. The part of agency that is not a myth for constructionists is the necessity of each individual to find ways to constructively adapt to or accept the dynamic conditions of postmodern work life.

Of note, all four previously mentioned discourses appear in the past 6 decades, though the rationalist discourse could feasibly be expected to be the apex of 400-year-old Enlightenment scientism. All in all, organizational change and agency do have a short history of approximately 60 years or so. But in that time, the nature of agency has changed from outside (external) consultants and academics, to both external and internal (usually HR) personnel, to “front-page” leadership personnel, to everyone in the organization in the form of teams and empowered workers, and ultimately to each individual worker.

That being said, however, many of the issues around which organizational change is initiated, and many of the issues involved with actual organizational changes, are ones that have persisted from the time when change agency first became an important phenomenon to study. Such issues concern the relationships and tensions between freedom and authority, the work organization and individual human spirit, productivity and worker satisfaction, and managerial control and employee voice—in short, the relationship of organizations and people—and are thus more or less universal. In the next section, I will use this dialectic in an effort to schematize the nature and kinds of change agency.

Types Of Organizational Change And Agency

The past 2 decades have witnessed exponentially increasing interest in the concept and phenomena of organizational change. This intrigue has become manifest in academic literature, periodicals in the popular business press, as well as in guidebooks and manuals for internal OD practitioners and external consultants. It is possible to discuss organizational change from several political dimensions, numerous theoretical perspectives, a multiplicity of organizational levels, and a seemingly inexhaustible list of change tools, tasks, and agent characteristics. The nature and function of change agency will differ along these discussions, as will the necessary functions and characteristics associated with effective change agents.

In the following pages, I offer schemata that I believe to be more or less comprehensive but heuristically viable at the same time.

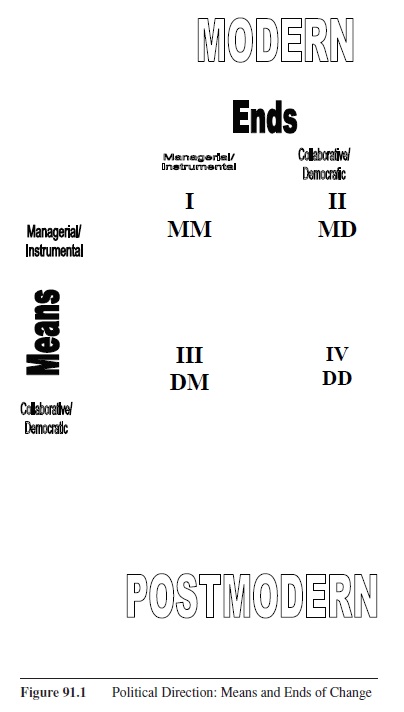

In Figure 91.1, we can first distinguish organizational change in terms of both philosophy and political direction; by political direction, I mean the means-ends construct, or the objectives of organizational change and how it achieves these objectives.

The entire scheme can be first distinguished by whether a conception of change agency is built on modernist or postmodernist assumptions. Modernist assumptions are those that retain Enlightenment scientism as an understanding of the nature of the world and how it works. An objective world, studied objectively (as science does), provides rational knowledge and objective truth about the world. Those that possess knowledge and truth—educated, enlightened, or divine—thus have power and expertise and are able to “impart” that knowledge to others. Such epistemological distinctions give rise to a whole host of beliefs about structure, authority, linear progress, and institutionalized power and knowledge upon which conventional organizational life is built.

Postmodern assumptions are those that reject modernist assumptions. Broadly, postmodern assumptions reject the idea of a “grand narrative”—an overriding conception of knowledge, truth, power, and authority—of anything. Thus, for postmodern thinkers, any sort formalized power should be resisted; institutionalized knowledge, in the form of academic discourses, for example, is just one form of knowledge that is no more viable on its face than any other form of knowledge; conventional organizational structure is no more viable than any other kind of structure, and regulated organizational practices are no more viable than less or unregulated practices.

The quadrants or windows in Figure 91.1 represent the political intent of change agency in terms of means and ends. Ends and means can be considered from both a managerialist/instrumental perspective and a choice/ democratic perspective. The former denotes an overall or primary interest in traditional concepts and practices of managerial control for the instrumental accomplishment of organizational goals. The latter denotes an overall or primary interest in those concepts and practices associated with democratic “control” for the participative or “collaborative” accomplishment of organizational goals. Consequently, the nature of change agency can be distinguished in the four ways indicated by each window I-IV in the chart.

- MI means, MI ends (maintaining instrumental control)

- MI means, CD ends (rational, expert-driven democracy)

- CD means, MI ends (formally democratic teams and communities)

Figure 91.1 Political Direction: Means and Ends of Change

Figure 91.1 Political Direction: Means and Ends of Change

Managerialist Means, Managerialist Ends

Type I organizational change is predominantly characterized as strategic and planned. The objectives of the change are conceived in terms of greater efficiency, productivity and bottom-line profitability. Type I organizational change is typically “rolled out” from the top of an organization where organizational expertise is vested, and it is thus driven by the agency of organizational leadership. Typically, but not necessarily, a strategy, productivity, or performance consultant assists organizational leadership in the design of the change.

Managerialist Means, Democratic Ends

Window II represents perhaps the most salient and persistent features of change agency as we know it today, and it is perhaps the original form of change agency. Type II change agency is not “managerialist” in the strict sense of control and accountability, but would be accurately characterized by modernist assumptions. In this kind of change, “expertise” is retained in the form of a consultant using a linear, rational model of change. The change model of Lewin—unfreeze-change-refreeze—is perhaps the proto-typical example of this type of change and is practiced by nearly all agents in the Lewinan tradition in early decades of organizational change agency (e.g., Argyris, 1993, 1994; Schein, 1995).

Importantly, though Type II change is based on modernist assumptions and is managerialist or instrumentalist in its means, note that it is a “benevolent” instrumentalism. Type II change employs therapeutic or helping interventions for enhancement of the human spirit and for communication and greater understanding, hence, equality at work—that is, for a more cooperative, collaborative, participative workplace. It is intended instrumentally to help the clients of change achieve a more democratic organization, ultimately as a model of what a better democratic society would look like. This type of change agency characterizes many of the heroes and renegades discussed by Kleiner (1996) as the originators or organizational change.

Democratic Means, Managerial Ends

Organizational change depicted by this window is by some accounts a sinister phenomenon. Here, the responsibility for change is democratically pushed down, delegated, or relinquished to what are often called teams. Empowered, participative teamwork appears not to have to operate within the constraints of formal authority, executive leadership, power, or expertise. However, teams are still circumscribed by explicit organizational goals, so that the apparent freedom offered by the delegation of authority and expertise remains confined to the service of status quo managerial objectives.

Democratic Means, Democratic Ends

Type IV change agency is denoted by those efforts to democratically organize a better democracy (wider empowerment, fuller participation, and employee voice) in an organization. The most common form of this kind of agency is the labor union, but the labor union is perhaps more formalized than democratic means-democratic ends (DD) change intends. DD change represents more of a grass-roots phenomenon, activities initiated by comparatively powerless workers, and uninfluenced by extant organizational power/authority/expertise, structure, or hierarchy.

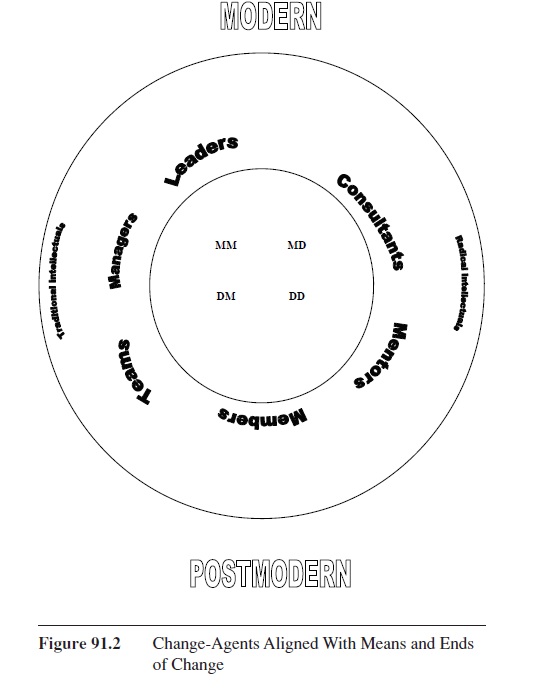

As you can easily surmise, the characteristics and functions of an effective change agent will not be the same for each type of change. In Figure 91.2, I have aligned potential agents of change with the type of change in which they would most likely be effective.

Change Agent Roles And Characteristics

As implied by the previous discussion of the types of possible change in an organization, the actual agency of change may come from anywhere in an organization, or perhaps from some places outside of an organization. In Figure 91.2, I have overlain seven potential role possibilities for change agency and aligned them with the type of change with which they are most likely to be associated.

Figure 91.2 Change-Agents Aligned With Means and Ends of Change

Figure 91.2 Change-Agents Aligned With Means and Ends of Change

Organizational Leaders as Change Agents: A Knowing and Telling Role

The role that organizational leaders have in change and as agency is simultaneously clear and complex. Organizational leaders—executive-level decision makers and CEOs—are often those in the best position to sense the effectiveness of current strategic plans, the viability of current strategic objectives, and environmental conditions pertaining to acquiring organizational intelligence and competition. In this sense, they are the agents that know what is to be done and how to do it, and thus, they tell others what to do.

In fact, in the 1980s as American organizations faced unprecedented international competition for the production of goods and services and thus attempted culture change on massive scale, most of the practical and academic literature about change concerned organizational leaders as the primary agents of change. Studies and stories abounded about the qualities and characteristics of organizational leaders who successfully transformed their organizations into more competitive organizations. As a result, most of what we have come to understand about the change agency of organizational leaders is a (slightly revised) form of leadership characteristics. Many such lists of characteristics appear on Web sites even today. A partial list includes strength, courage, desire to lead, self-confidence, personal drive, and cognitive ability.

However, the conventional perception of a powerful organizational leader as the single catalyst for change has been replaced in the past few years with a conception of change leadership—a role feasibly open to anyone. However, that revised conception is also accompanied by a more contemporary, revised list of characteristics—for example, flexibility, empowerment of others, desire to serve others, enhanced emotional intelligence, and continuing self-development.

All of that being said, in today’s organizations, the actual role that executive leadership plays in change is confounded by a number of contingencies.

Formal Authority

Certainly, at least in organizations that share the more or less conventional notion of “hierarchy,” the executive and directive power to accomplish change lies with this class of organizational decision makers. Yet that authority can be used in ways that increase resistance to change, cultivate increased fear and insecurity about change (even though there might be formal compliance), and ultimately interfere with effective change procedures. It does not have to, but it can. If a type of genuine or authentic authority can be derived from the formal authority, organizational leaders place themselves in a much better position as the agency of change. Genuine authority is benevolent. It comes from a sense of self that is fulfilled. It is directed toward a vision of a better organization that means better for the people that make the organization. It is empowering and enabling, not just directing change but also facilitating it by one’s own example and model.

Time

No matter how committed or passionate a corporate leader may be about a change initiative, more often than not they simply do not have the time to be involved in every stage of the change process. While managers or organizational members may look to the executive level for leadership of the change, leadership often wonders why the management level seems to lack the competence or confidence to carry out the change.

A good part of this disconnect concerns the executive’s responsibility to communicate change effectively to key personnel involved with the change. Many are both unfamiliar with the acute value of such communication and time requirements of crafting an effective communication plan.

The Wet Work

Organizational leaders are responsible for the fiscal health of the organization and, of course, for all of the technological and human resources that constitute a fiscally healthy organization. Yet, similar to the time constraints just mentioned, their ability or inclination to manage every step or to be involved in every meeting or activity is limited. However, their participation in the wet work does include the enablement and empowerment of others to get the work done, as well as providing the necessary resources.

More Effective in Other Roles (Associated With Change Agency)

Increasing research from both academic and practical contexts points to a change role for the organizational leader as a sponsor or champion of change. Indeed, such research indicates a great likelihood of failure on the part of change teams and individual change agents without the sponsorship of someone at the executive level. The responsibilities here include public endorsements of the change, communicating often in both formal and informal contexts with all relevant stakeholders in the change process, building networks and coalitions in support of the change, as well as perhaps many “hallway” conversations and discussions with relevant change agents and constituents.

Organizational Manager as Change Agent: A Performing Role

Perhaps because of the same myriad of forces that affected more traditional notions of organizational leader as change agent, managers have increasingly found that any agency role in organizational change process has come to be defined more or less for them rather than chosen by them. As the past 2 decades have produced rampant organizational culture changes, downsizing, and flatter organizational structures, two sets of forces have converged upon managers to define their change role. First, managers have been on the receiving end of most of the responsibilities for the wet work of change programs. This is because change activity is usually a planned process amenable to the conventional understanding of what managers do—plan, control, organize, and direct. Consequently, most of what appears in the popular business press about change is actually change management—prescriptions, advice, or best/worst case scenarios for how to manage change effectively.

But second, as cultures and functions changed with newer, leaner, more nimble, and dynamic structures, management finds its conventional roles redefined into that of encouraging participation, empowering others, getting others to be receptive to and involved in change efforts. This becomes a rather stressful dilemma: Managers must manage both up and down, making them both the agency of change as well as an object of change. Redefined management roles require softer people management skills, but success in management is in essence a fiercely competitive endeavor. Thus, the manager’s mode of agency in the change process could be called performing.

Teams as Change Agency: Still Performing

The idea of organizational teams (not groups of individuals) functioning as change agents results from the same forces as affect leaders and managers. Teams and teamwork emerged in the 1990s because of the widespread corporate interest in reculturing organizations in the 1980s. Although the synergistic and holistic properties and effectiveness of groups had been noted by social psychologists several decades earlier, it was not until cross-functional collaboration became a necessary organizational reality (or the inevitable residue of the “participation” required by downsizing), that teams emerged as a legitimate organizational entity.

The capacity of teams for change agency comes in two forms. First, there is the original notion of the “cross-functional” team. This group, usually composed of several members of various functional units across an organization, was given complete responsibility for a particular project, as well as the charge of overall “continuous improvement” of production, coordination, or business processes. However, the team construct is characterized by greater flexibility and more creativity in its work than is provided by the conventional managerial unilateral span of control. The skill set required to fully utilize this greater creativity and flexibility is often trained into the group, in the form of better communication skills, training in group dynamics, conflict resolution, effective listening, and alternative modes of thinking and problem solving. This creativity and flexibility is put to work in the service of innovation in services, products and work processes, and hence possess an agency for organizational change.

Note that I have aligned teams in the bottom left corner of Figure 91.2, indicating that they are a postmodern phenomenon; power is formally pushed down or dispersed to the team, so at least formally the means of potential change agency are democratic. However, teams are inherently designed to achieve managerial ends. That is, the team responsibility is an even further devolved phenomenon of agency—from manager to team.

In my discussion of that quadrant of Type III agency, I noted that it may be seen as sinister. In this sense, teams (and change-agent managers, for that matter) are bound by a sort of paradox that awards them creativity and flexibility, but to be used within and to achieve organizational objectives. Some academic writers have noted that the paradox is a sort of invisible discipline—not the kind that comes from the explicit unilateral control of a manager, but from the inside of each group member as they now have to engage in a kind of self-surveillance of their creative and relational selves to achieve group effectiveness.

Also note that while the change agency of cross-functional teams does reach for innovation, rarely does the flexibility or creativity allow them to transcend extant organizational goals and controls. Thus, the agency of cross-functional teams for larger, systemwide transformations is limited.

A second kind of change capacity that currently accrues to teams is that of learning. Popularized in the past decade as a mechanism for organizational learning and the learning organization, teams are taught to think more holistically or systemically about projects and processes. Informed largely by recent resurrections of the nonlinear dimension of system dynamics, teams are thought to be able to see not the short-term picture or quick-fix solution, but rather the implications of any project for the long-term sustainability of the organization. Teams learn and, thus, acquire change agency, not only when they solve problems for better products or services, but also when they learn how to learn together. This requires a skill set that even today is unfamiliar and largely resisted—that of not just talking together, but exposing and examining the assumptions behind ideas; learning to suspend our own ideas and judgments of other’s ideas, to engage in dialogue and not be concerned about winning or making our point.

By all academic accounts, the capacity for change agency accruing to this kind of team could be immense. Not just in terms of the problems addressed by learning teams, but in the collaboration and relational processes involved with this teamwork. By supportive academic accounts, this is the mechanism for holistic, large-scale, systemwide transformation. And if the organizational change is a model for societal and global change, then these as well. However, there are few, if any, reports published in peer-reviewed academic journals of organizational learning practitioners ever changing anything through teams in this way.

This capacity for change agency is attractive, optimistic, and hopeful. Nevertheless, this hypothetical capacity is limited by significant concerns about organizational politics and power, in both interpersonal and group contexts. First, is it possible for individual organizational members—regardless of a tremendous commitment to group effectiveness—to achieve this ideal form of interaction and collaboration? Second, how can such optimal relational processes—the core of the learning team—be diffused throughout an organization?

Despite the potential of learning teams, and because of the more or less traditional managerial ends associated with cross-functional teams, the modality of the agency for teams is that of performing. Interestingly, as with change leadership and change management, change teams are now a necessary mechanism for undertaking significant organizational change. Similar to a cross-functional team in composition, but having the characteristics and functions of a change manager, such teams are responsible for implementing change across organizational boundaries, functions, and levels.

Consultants as Change Agents: A Helping Role

Perhaps the most discussed and visible kind of change agency in the past one half of a century is that of the external organizational consultant. Consultants are both lauded and despised in the relevant literature, their function once publicly characterized as “witch doctoring.” Nevertheless, although their glamorous popularity may have waned since the 1980s, rare is the organizational leader or manager who would initiate a change initiative—for strategy, technology, structure, or people—without the expertise of a consultant.

I have aligned consultants with Type II change agency, which indicates instrumental means for democratic ends. This is perhaps my own subjective preference, my sentiment, if you will, as this was the process type consultation activated by the original change agents in the mid-20th century, ultimately in the hope of producing a more democratic organization for a more democratic society. As more organizational change is devoted to issues of people, participation and stakeholder relevance, this type of change and agency will continue to retain its original importance for some time to come.

Consultants could just as easily have been included on the left side of Figure 91.2 to identify those strategy, performance, or productivity consultants who specialize mostly in subsystem, remedial, or incremental change or in making recommendations as to bigger picture change. This group would also include those consultants who specialize in building more effective teams, or management development consultants who build more effective managers, often training both in the new or soft skills required by today’s organizations.

Either way, the consultant as change agent could have a multitude of functions, depending upon specialty area of expertise, and particular methodology. These could include any combination of advising, assessing, diagnosing, implementing, training, developing, and evaluating outcomes of change programs. Strategy consultants primarily assess, advise, and make recommendations. Typically, strategy consultants rarely intervene in the systems they assess, though an increasingly common subspecialty of strategy consultation focuses on managing or oversight of the implementation process, similar to change management. Performance or productivity consultants typically assess, advise as to what needs to be done, design and/or develop training, and then turn the training process over to in-house training personnel.

However, I characterize the primary modality of this kind of change agency as helping in much the way a doctor helps a client who seeks treatment or counsel. On this model, one of the primary functions of a consultant is to intervene and change the system they are studying. Lewin, perhaps the first organizational consultant-change agent, is reported to have said, “You cannot understand a system unless you try to change it” (reported in Schein, 1995, and in Kleiner, 1996).

This is the dictum for thoughtful, solid, interventionist work, found in the process consulting work of Schein (1995), Argyris (1993, 1994), and others in Lewin’s tradition.

Intellectuals as Change Agents: An Advising Role

This may seem an odd entry in a compendium of 21st-century management issues. In fact, two of my most favorite quotations would mitigate against its inclusion. The first is the classic Marxian statement from his Theses on Feuerbach: “Philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it.” The other is much more contemporary, from postmodern commentator Clegg (1990): “Intellectuals don’t legislate easily on the meaning of the world anymore; if they do, hardly anyone is listening.”

My sentiment for such quotations is located in my desire for actual, rather than theoretical, organizational and social change. At the same time, the quotations reflect an almost insurmountable gap between the theory of change and the practice of change. Change is a practical, not a theoretical phenomenon.

In fact, the model for intellectual as change agent has its origin in the Enlightenment, as groups of writers and thinkers called philosophes became social commentators, as well as advisors to kings and nobles. This group of intellectuals is primarily responsible for interpreting and disseminating the thoughts of philosophers concerning science and democracy, activities that were directly contributive to both a revolution and massive social change, on two continents.

Note that these two main engines of the Enlightenment— science and democracy—still power most if not all of our thinking about the world 400 years later.

Intellectuals can have a similar function today, to the extent that theory can be derived from practical applied knowledge, and practical, applied knowledge can be derived from theory. This would involve a host of changes in the ways intellectuals do their work, but perhaps foremost among them would be the desire to make academic research available to the working public. Postmodern commentator Baumann (1987) has proposed a viable role for the contemporary intellectual—that of interpreting the theoretical work for the popular audience and practical application.

It may be instructive to distinguish intellectuals into two very broad categories that correspond roughly to Figure 91.2.

Traditional intellectuals would be those whose theoretical, research, and other academic work contributes to a broad understanding of organizational theory, management and change from a conventional managerial perspective, and within a conventional managerial paradigm. Though innovative and perhaps revolutionary in their time, the culture work of Peters and Waterman or of Deal and Kennedy might be considered such work in that their aim was to strengthen traditional American organizations for increasing global competition. Other more contemporary business/management intellectuals that come to mind might be Thurow, Porter, Kotter, McGregor Burns, and certainly, Drucker fits the category. Sometimes the intellectual work of these people drives lucrative consulting practices; sometimes it rather contributes to the body of academic knowledge only.

Radical intellectuals, for lack of a better term, would be those who theorize and speculate not necessarily about how we can be more competitive, manage or lead more effectively, be more productive, be more satisfied at work, or in general work better, but about the nature and necessity of work itself—the arbitrary imposed distinctions between work and life, unquestioned assumptions about the nature of authority, and structure and subordination.

Such intellectuals tend to see the organization of work as overdetermined in the first place. Most intellectual work of this nature derives from the “critical” program of organizational and management study and sees the work organization as a site of domination—that is, unnecessarily restrictive of human freedom and dignity—and as having “colonized” our nonwork life. The overall goal of the writing of these intellectuals is a more liberated or freely chosen set of work options, circumstances, and structures on the part of workers.

Curiously, no published reports indicate that the writing of these intellectuals has ever liberated anyone from anything. However, we may note that participative management schemes, empowerment initiatives, and increasingly flexible work-life balance options tend to reflect the sentiment of the radical intellectual. Additionally, as I have written elsewhere, the aims and aspirations of organizational learning as well as much of the applied interventionist work it offers, very closely resembles the goals and tenets of the radical intellectual in the critical program.

Teachers as Change Agents: An Enlightening Role

I have not included teachers in Figure 91.2, because they could be located anywhere. The teacher, especially a university instructor or professor but any teacher really, is in the most viable position for change agency outside the actual organization. Teaching may be that role described by Baumann (1987) as interpreting, using theory to cultivate practice, or using theory to critique other theories. It may seem quaint, but it is true: Ask any successful person for the most influential person in his or her life, and he or she will point to a teacher.

A passionate, enthusiastic teacher with pedagogically sound methods literally frames the way a learner receives and interprets information. Consequently, a teacher’s change agency lies in the way information is framed. A teacher can frame accepted wisdom in conventional ways for a mainstream understanding; or new ideas can be cultivated in unconventional ways for an alternative understanding. Unfortunately, most management education at the university level proceeds by way of the former: bound by accreditation standards and market-driven curricula, there is little if any latitude for alternative or unconventional understandings. That being said, the passionate teacher committed to the ideals he or she envisions may always be able to find agency in the materials and methods employed.

For example, unless one were to dig deep into the history of organizational development or to be very familiar with the theory and principles of systems design, one would not ordinarily recognize the name Jay Forrester. Yet, any OD specialist or consultant worth half of their salary would know about organizational learning and the name Senge. Forrester was Senge’s teacher and, in some respects, his mentor. Forrester wrote and thought great things, some of which had an impact at the time. But the overwhelm-ing significance of Forrester’s thought for contemporary management and organization theory might still be dormant if not for Senge (1992) bringing them back to life as the systems principles of The Fifth Discipline. And the impact of The Fifth Discipline is unmistakable. My point is that teachers (and mentors) can be change agents—indeed should be—whose influence may not be felt or known until much later.

Mentors as Change Agents: An Action Role

As I have written elsewhere, the agency of the mentoring process in organizational change has been grossly undervalued or overlooked altogether. Although mentoring has become a popular topic in recent years, there is not much to indicate that its study or practice has changed much from conventional notions.

Mentoring involves a dyadic relationship, usually between a senior experienced member of an organization and a junior inexperienced member. Traditionally, the objective of mentoring has been for the mentor to pass on his or her accumulated wisdom regarding task competence, managerial skill, and political awareness to the protégé, for the efficient development of the protégé. As mentoring is a dyadic relationship, I believe the nature of this relationship defines or circumscribes the potential of change agency in mentoring.

Mentoring can be designed as a traditional learning, or developmental relationship, where the objective is the development of the protégé. This is accomplished by the mentoring transmitting all relevant cultural, political, and task knowledge to the protégé in the form of extant organizational wisdom. Here, the protégé learns, but only in an incremental way—in Argyris’ (1993, 1994) terms, a single-loop way of correcting errors and doing things right or in the prescribed, accepted manner. We can say that change is happening, but certainly not outside of accepted parameters.

Alternatively, if a mentor role is designed as a more therapeutic one (and mentors appropriately qualified and credentialed), significant change could possibly be observed even in within accepted parameters. Such changes may be in the form of an increased behavioral repertoire, enhanced personal mastery, improved decision making, and an openness to new learning. Some of these carry forward, as not simple error-corrections, but as generative preparation for novel experiences.

By contrast, we could view mentoring as what Argyris (1993, 1994) would call a double-loop enterprise—designed to explore, invent, examine unexamined organizational assumptions, ask unasked questions, and otherwise discuss the undiscussable.

This requires a different sort of relationship and interaction, one where the communication is not confined to transmitting information, but rather exploring possibilities and appreciating differences. Here, we have the potential for quantum generative change on the part of both mentor and protégé, as well as the potential for double-loop learning to be diffused throughout the organization.

I have called this modality of change action, as it takes place in actual organizational practice, in the dynamics of interpersonal interaction in organizations.

Organizational Members as Change Agents: An Activist Role

Unfortunately, but usually, far down on the priority list of organizational demands and constraints are the concerns and needs of the masses of organizational members. In fact, most of the preceding discussion features the change agency of organizational members with specific, visible roles, while the ordinary organizational member recedes into the background—their only role as that of having change “done to them.”

I have aligned members with Type IV agency, as most member concerns have to do with increased voice, choice, recognition, means for satisfaction, and participation—that is, democratic concerns. As finding formal means and channels to address such concerns is often a futile enterprise, change initiatives to address them are/must be organized democratically, as a grass-roots phenomenon, from the bottom up.

Can organizational members” in the invisible way the quote marks suggest, have any change agency? Many think so, and though perhaps difficult, it is not impossible to acquire and wield change agency from this perspective.

Tempered radicals is the name given by Meyerson (2003) to those workers who may be disenfranchised or alienated from their jobs or organization; perhaps very committed and loyal members who desperately want to see change but seem powerless to effect it; those like Meyer-son herself who felt “misaligned” with her profession and wondered why; perhaps managers caught in the constant daily squeeze of managing up and down; or those that find a home, family, personal, or social life nearly impossible with 24/7 accessibility by the organization via pager or Blackberry. These and folks like them tend to say “this has got to stop” a lot. But they may like their jobs and want to keep them; they may like their professions and want to stay in them. As Meyerson said, “[T]hey want to rock the boat and stay in it.”

But how does one change it with little means and usually no formal power? This kind of change agency starts with an assessment of self, what self really wants out of work and life, and what self can do to change things. This requires coming to an understanding that is consistent with both the external constraints of the situation as well as internal aspirations and desires. Organizational members can reach for this understanding at any of three levels: intrapersonally, by silent or psychological acts of resistance, or by seeing the opportunity involved in obstacles and threats; interpersonally, by engaging like-minded others in conversations or by finding the courage to negotiate for what you want in the face of power; or collectively, with a larger number of like-minded people. Some theorists suggest critical labor groups or shadow core groups that meet and discuss ways an organization stifles change and ways to accomplish it. All of these possess agency through their active resistance of an undesirable status quo.

The Success And Failure Of Change Initiatives

With all of this talk about agency, we would think that change happens a lot in organizations. It does not. An estimated average of 70% of all organizational change initiative fail, and that estimate has been steady for a decade.

The success of change initiatives is generally attributable to visible executive sponsorship of change including procuring adequate resources for the change, when executive sponsorship is coupled with management and when employees are informed about how to support the change. The failure of change is generally attributable to ineffective or conflicting leadership, unclear goals, and ineffective planning.

References:

- Argyris, C. (1993). Knowledge for action. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Argyris, C. (1994). On organizational learning. London: Blackwell. Argyris C., & Schon, D. (1978). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley. Baumann, Z. (1987). Legislators and interpreters. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Bokeno, R. M. (2000). Dialogic mentoring: Core relationships for organizational learning. Management Communication Quarterly, 14(2), 237-270.

- Bokeno, R. M. (2003). Introduction: Appraisals of organizational learning as an emancipatory project. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 16(6), 603-618.

- Caldwell, R. (2001). Champions, adapters, consultants and synergists: The new change-agents in HRM. Human Resource Management Journal, 11(3), 39-52.

- Caldwell, R. (2003). Models of change agency: A fourfold classification. British Journal of Management, 14(2), 131-142.

- Caldwell, R. (2005a). Agency and change. London: Routledge.

- Caldwell, R. (2005b). Things fall apart? Discourses on agency and change in organizations. Human Relations, 58(1), 83-114.

- Clegg, S. (1990). Modern organization. London: Sage. Data warehouse glossary. (n.d.). Information technology at California State University Monterey Bay. Retrieved September 8, 2007, from http://it.csumb.edu/departments/data/glossary.html

- Kleiner, A. (1996). The age of heretics: Heroes, outlaws and the forerunners of corporate change. New York: Currency Doubleday.

- Meyerson, D. (2003). Tempered radicals: How everyday leaders inspire change at work. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Schein, E. (1987). Process consultation. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley.

- Schein, E. (1995). Kurt Lewins change theory in the field and in the classroom: Notes toward a model of managed learning (Working Paper No. 10.006). Cambridge, MA: Center for Organizational Learning, MIT.

- Senge, P. (1992). The fifth discipline. New York: Currency Doubleday.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.