This sample Achievement Motivation in Academics Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

Achievement motivation is the desire to excel at effortful activities. Achievement motivation originally was thought of as extending across many areas, but current views conceive of it as more specific to situations. Personal, social, instructional, familial, and cultural factors affect achievement motivation, and parents and educators can help students to improve their achievement motivation.

Outline

- Introduction

- Background

- Current Perspectives

- Promoting Achievement Motivation

1. Introduction

At the end of her ninth-grade geometry class, Mrs. Lollar passed out the ‘‘Problem of the Week’’ for students to take home and solve. Two students in the class, Ashley and Marella, each have a B+ average. Because the problem of the week is worth extra credit, doing well on it could raise each of their averages to an A. That evening at home, Ashley looked at the problem for a while, spent a little time on it, but then quit without solving it. Marella studied the problem and began to work. When her parents called her to dinner, she was reluctant to come because she was working on it. After dinner, she worked on it some more and finally exclaimed, ‘‘Aha—I get it!’’ The next day in class, Marella was one of only three students to have solved the geometric proof. Ashley got some steps in the proof correct, but her solution was far from complete.

Achievement motivation is the desire to excel at effortful activities. In the opening scenario, it seems that Marella was more motivated to achieve in geometry than was Ashley. Marella displayed interest in solving the proof, persisted at it, was excited when she understood what to do, and solved it correctly.

Achievement motivation has a long history in psychology and education, and for good reason. Motivation to achieve is necessary for all but the simplest tasks. Achievement motivation helps students to learn in school, fuels creative activities, and helps individuals and societies to attain goals.

Despite the intuitive importance of achievement motivation, researchers disagree on its critical components. The next two sections examine the background of achievement motivation and some current perspectives.

2. Background

It is difficult to pinpoint the historical onset of the study of achievement motivation because the human desire to achieve has been of interest for ages. The scientific study of achievement motivation received impetus from work by Murray, who included it as one of several human needs that contribute to personality development. Murray also devised the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) to study personality processes. The TAT is a projective technique in which people view a series of ambiguous pictures (i.e., inkblots) and make up a story or answer questions for each picture.

McClelland and colleagues adapted the TAT to study achievement motivation. People were shown pictures of individuals in ambiguous situations (e.g., a student at a desk holding a pencil and looking into the air) and were asked questions such as the following: ‘‘What is happening?,’’ ‘‘What led up to this situation?,’’ ‘‘What is wanted?,’’ and ‘‘What will happen?’’ Responses were scored and categorized according to strength of achievement motivation. Unfortunately the TAT has some measurement problems, and TAT achievement motivation scores often did not relate well to other measures of achievement. Over the years, researchers have devised other methods for assessing achievement motivation.

Important early work on achievement motivation was done by Atkinson and colleagues. Atkinson drew on work by Lewin and others on the level of aspiration or the goal that people set in a task. Lewin’s research showed that successes raised and failures lowered the level of aspiration, that people felt more successful when they met the goals they had set for themselves than when they attained objective standards, and that the level of aspiration reflected individual and group differences.

Atkinson’s expectancy–value theory of achievement motivation states that behavior depends on how much people value a particular goal and their expectancy of attaining that goal as a result of performing in a given fashion. Atkinson postulated that achievement behavior involved a conflict between a motive to approach a task (hope for success) and a motive to avoid it (fear of failure). These motives conflict because any achievement task carries with it the possibilities of success and failure. The achievement motivation that results in any situation depends on people’s expectancies of success and failure and their incentive values of success and failure.

The historical research focused on achievement motivation globally, that is, motivation across many situations. But research and everyday observations show that people rarely are motivated to achieve at high levels in every situation. Rather, students typically have greater achievement motivation in some content areas than in others. In the opening scenario, although Marella’s achievement motivation was higher than Ashley’s in geometry, Ashley may strive to excel more than Marella in history. Given that the achievement motive differs depending on the domain (and even depending on the task within the domain), the validity of general achievement motivation is questionable.

3. Current Perspectives

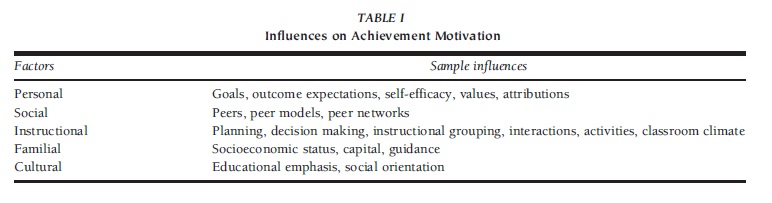

People who study achievement motivation today believe that it is more situationally specific and is affected by many factors: personal, social, instructional, familial, and cultural (Table I). To understand why students differ in achievement motivation, one must examine the roles of these factors in their lives. Although researchers agree that achievement motivation is complex, they disagree on which factors are the most important.

Personal factors reside within students. Some key personal factors are goals, expectations, values, and attributions. Goals are what one is trying to accomplish. Goals usually are cast in terms of products—Marella and Ashley’s goal was to work the geometry proof—but they also can represent processes. Thus, an academic goal may be to improve one’s skill in comprehending scientific texts. Goals contribute to achievement motivation because people pursuing goals persist and expend effort to succeed. As they work on the tasks, they evaluate their goal processes, and the belief that they are making progress sustains motivation.

TABLE I Influences on Achievement Motivation

TABLE I Influences on Achievement Motivation

But goals actually are less important than their properties: specificity, proximity, and difficulty. Goals may be specific (e.g., read 10 pages) or general (e.g., read some pages), proximal (e.g., read 10 pages tonight) or distant (e.g., read 10 pages by next week), and difficult (e.g., read 400 pages) or easier (e.g., read 50 pages). From a motivational perspective, goals that are specific, proximal, and moderately difficult produce higher achievement motivation than do goals that are general, distant, and either too difficult or too easy. Thus, motivation is not aided when goals denote general outcomes (because nearly any action will satisfy them), are temporally distant (it is easy to put off until tomorrow what does not need to be done today), and too difficult or too easy (people are not motivated to attempt the impossible and may procrastinate completing easy tasks).

Expectations can be of two types. Outcome expectations refer to the expected outcomes of one’s actions (e.g., ‘‘If I study hard, I should make a high grade on the test,’’ ‘‘No matter how hard I study, I probably will fail the test’’). Outcome expectations motivate students because the belief that a certain action will lead to a given outcome should lead students to pursue or avoid that action, assuming that they value that outcome or want to avoid it.

A second type of expectation involves beliefs about one’s capabilities to learn or perform given actions. Bandura and other researchers termed this ‘‘self-efficacy.’’ Self-efficacious students believe that they can study diligently, whereas those lacking efficacy might believe that they cannot. Marella’s self-efficacy in geometry likely was higher than Ashley’s. Self-efficacy is important because students who believe that they can learn or perform desired actions are more likely to choose to engage in them, expend effort, and persist.

Self-efficacy and outcome expectations often are related, but they need not be. Students who believe that they are capable typically expect to perform well and receive high grades and other rewards. However, students may believe that diligent studying will lead to good grades (i.e., positive outcome expectation) but also may doubt their ability to study diligently (i.e., low self-efficacy), in which case they might feel demoralized. Positive outcome expectations and strong self-efficacy for learning and performing capably produce high achievement motivation.

The values and/or importance that students ascribe to learning and achievement are central components of motivation. Those who do not value what they are learning are not motivated to improve or perform well. Research shows that value relates positively to persistence, choice, and performance. Students who value learning choose challenging activities, persist at them, and perform well. Thus, students who value history are apt to study diligently for tests, set goals for their learning, monitor their learning progress, use effective learning strategies, and not be daunted by obstacles. Marella likely valued geometry more than did Ashley.

Attributions are perceived causes of outcomes or the factors that people believe are responsible for their successes and failures. In achievement situations, learners may ask themselves questions such as the following: ‘‘Why did I get an A on my biology test?’’ and ‘‘Why can’t I learn French?’’

Weiner and colleagues formulated an attribution theory of achievement motivation that contends that each attribution can be classified along three dimensions: locus, stability, and controllability. The locus dimension refers to whether the attribution is internal or external to the person. The stability dimension denotes how much the attribution varies over time. The controllability dimension involves the extent that the attribution is under the individual’s control.

Weiner found that common attributions in achievement settings are ability, luck, task difficulty, and effort; however, there are many others (e.g., fatigue, illness, personal dislike, time available, attitude). Ability is internal, stable, and uncontrollable (although one’s ability can improve over time); luck is external, unstable, and uncontrollable; task difficulty is external, stable (assuming that the task does not change), and uncontrollable; and effort is internal, unstable (although a general effort factor also seems to exist), and controllable.

Students who attribute academic success to high ability and effort are more likely to expect future success than are those who attribute it to task ease and good luck. Students who attribute failure to low ability are less likely to expect future success than are those who attribute it to low effort. The latter finding is especially critical because a low expectation of future success stifles motivation. From the perspective of achievement motivation, it is far better to stress effort than ability because the former has stronger motivational effects. Of course, as skills develop, students do become more able, so the attribution of success to ability is credible. Teachers often have difficulty in motivating students who believe that they lack the ability to succeed and that no amount of effort will help them to be successful.

Social factors are those that are inherent in interactions with others. Peers are a key social group for students. Peer models are especially influential, especially those who are similar to observers in important ways, because they convey that tasks are valuable.

Peer group goals are highly valued by students. Thus, students may want to be liked and approved, develop social and/or intimate relationships, learn to cooperate, win favors, and be sensitive to the needs of others. Students’ perceptions of their capabilities also are affected by peers through social comparisons. Observing similar peers succeeding can raise observers’ self-efficacy.

Peer networks are large groups of peers with whom students associate. Students in networks tend to be highly similar and, thus, are key models. Students’ motivational engagement in school across the school year is predicted by their network membership at the start of the year. Those in more academically inclined networks demonstrate higher academic motivation than do those in low-motivation networks.

Although students may select their peer networks, parents can play a key role by ‘‘launching’’ their children onto particular trajectories. For example, parents who want their children to be academically oriented are likely to involve them in activities and groups that stress academics. Peers with whom children associate reinforce the emphasis on academics.

Instructional factors include teacher planning and decision making, grouping for instruction, teacher–student interactions (including feedback to students), activities, and classroom climate. Teachers can enhance student

motivation by planning interesting activities that maximize student involvement in lessons. Teachers who plan only lectures are less apt to promote student motivation. Teachers also can promote motivation by basing instructional decisions not only on how well students are learning but also on how much the material appeals to students.

Three types of grouping structures are competitive, cooperative, and individualist. Competitive situations are those in which the goals of individuals are linked negatively such that if one attains his or her goal, the chance that others will attain their goals diminishes. Cooperative structures are those in which the goals of the group members are linked positively such that one can attain his or her goal only if others attain their goals. In individualist situations, there is no link among the goals of individuals such that one’s goal attainment has no effect on the goal attainment of others. From a motivational perspective, competitive situations highlight differences among students, and lower achievers may become discouraged if they believe that they have no chance to earn rewards. Cooperative situations are better if all students contribute to the project. If only one or two students do most of the work, there is apt to be resentment. In individualist situations, achievement motivation can be developed and sustained when learners focus on their progress or on how much better they are performing now compared with earlier.

Performance feedback provides information on accuracy of work and may include corrective information (e.g., ‘‘The first part is correct, but you need to bring down the next number’’). Motivational feedback can provide information on progress and competence (e.g., ‘‘You’ve gotten much better at this’’), link student performance with one or more attributions (e.g., ‘‘You’ve been working hard’’), and inform students about how well they are applying a strategy and how strategy use is improving their work (e.g., ‘‘You got it correct because you followed the proper method’’). Feedback motivates students when it informs them that they are making progress and becoming more competent.

Classroom climate refers to the atmosphere of the classroom—its social, psychological, and emotional characteristics. Climate is important for motivation because classroom interactions define the climate. Climate often is referred to in terms such as ‘‘warm,’’ ‘‘cold,’’ ‘‘permissive,’’ ‘‘democratic,’’ and ‘‘autocratic.’’ Research shows that a democratic environment—one based on mutual respect and collaboration—fosters goal attainment by learners without their becoming frustrated or aggressive.

There are many familial factors, but a key one is socioeconomic status, whose link with students’ academic motivation is well established. Children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds typically display lower motivation and achievement, and are at greater risk for school failure and dropout, compared with children from wealthier families. But socioeconomic status is only a descriptive term and does not explain why effects occur. There also are many people who grew up in impoverished environments but became well educated and successful.

A major contributor is a family’s capital or resources.

Poor families have less financial resources to support their children’s learning outside of school than do wealthier families. Socialization in lower class homes often does not match or prepare students for the middle-class orientation of schools and classrooms. Lower socioeconomic students might not understand the full benefits of schooling or comprehend that getting a good education will increase their chances of college acceptance, good jobs, and financial stability. Because of family financial strain, they also might not be able to resist the short-term benefits of working in favor of the long-term benefits of schooling. Such students might have few, if any, educated role models in their environments. Many enter school without the needed social, cognitive, and emotional prerequisites to learn successfully.

Families continue to influence children’s motivation throughout childhood and adolescence by steering children in given directions. Families that provide rich resources in the home and guide their children into activities that stress motivation and achievement are apt to develop children higher in achievement motivation.

Cultural factors also affect motivation. Cross-cultural research shows that there are differences in how much cultures emphasize education and motivation for learning. For example, children from Asian cultures often place greater emphasis on effort as a cause of success than do students in the United States. Some cultures are more socially oriented, whereas others place more emphasis on individual accomplishments. Although it is hard to make generalizations about cultures given that not all members of a culture act alike, it does seem that motivational differences stem in part from influences in cultural background.

4. Promoting Achievement Motivation

How can parents and educators help to improve students’ achievement motivation for academics? First, they can help students to set challenging but attainable goals. Students must believe that the goals are attainable; they will not be motivated to attempt what they see as impossible. Teachers and parents might need to work with students to ensure that goals are realistic; if students are unaware of the demands of an assignment, they might set an unattainable goal. Challenging and attainable goals help to build self-efficacy as students perceive that they are making progress.

Second, it is important for parents and educators to stress the value of learning. Motivation is enhanced when learners understand how they can use what they are learning and how it will help them in the future. People are not motivated to engage in ‘‘busy work.’’ Marella and Ashley’s teacher would do well to point out applications of geometry in daily life.

Third, parents and educators should build students’ perceptions of their competence or self-efficacy. Self efficacy is increased when learners believe that they are developing skills, making progress toward their goals, and performing better. Self-efficacy develops through actual performance accomplishments, vicarious (modeled) experiences, and social persuasion. Teachers and parents should ensure that students work at tasks on which they can be successful, observe similar peers succeeding, and receive feedback indicating that they are capable (e.g., ‘‘I know you can do this’’).

Fourth, parents should get involved in children’s learning. Parents can be involved in school by assisting in classrooms and at home. Parents serve as models for learning, and they can help to establish a productive study environment. They also can be taught tutoring skills. The importance of parents as motivational models cannot be overemphasized.

Fifth, teachers should use peers effectively to build motivation. Teachers who group students for collaborative project work must ensure that each student has responsibility for part of the task so that the bulk of the work is not done by one or two students. In using models for comparisons, it is imperative that students view the models as similar to themselves. Motivation of lower achieving students might not improve when these students are asked to observe higher achieving students perform.

Finally, parents and educators should use feedback to teach and motivate. Feedback typically informs students whether they are correct or incorrect and what to do to perform better. Feedback motivates when it informs students about their progress—how much better they are performing now than they were previously—and when it links their performances to effort, good strategy use, and enhanced ability.

Academic motivation for academics is important not only for schooling but also for the future. Educators want students to continue to be motivated to learn once they leave their classrooms. This is the essence of ‘‘lifelong learning’’ by which citizens move their societies forward.

References:

- Ames, C. (1984). Competitive, cooperative, and individualistic goal structures: A cognitive–motivational analysis. In R. Ames, & Ames (Eds.), Research on motivation in education (Vol. 1, pp. 177–207). New York: Academic Press.

- Atkinson, W. (1957). Motivational determinants of risk-taking behavior. Psychological Review, 64, 359–372.

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

- Bradley, R. H., & Corwyn, R. F. (2002). Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 371–399.

- McClelland, D., Atkinson, J. W., Clark, R. A., & Lowell, E. L. (1953). The achievement motive. New York: Appleton– Century–Crofts.

- Murray, H. A. (1938). Explorations in personality. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Pintrich, P. R., & Schunk, D. H. (2002). Motivation in education: Theory, research, and applications (2nd ). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/Prentice Hall.

- Steinberg, , Brown, B. B., & Dornbusch, S. M. (1996). Beyond the classroom: Why school reform has failed and what parents need to do. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Weiner, (1992). Human motivation: Metaphors, theories, and research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.