This sample Behavioral Medicine Issues in Late Life Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

Behavioral medicine encompasses the study of how behavior impacts the onset, progression, and recovery from illness and the application of those behavioral factors to promoting health and preventing illness. Due to national demographic trends and the prevalence of chronic diseases in late life, older adults are emerging as a critical target group for behavioral medicine interventions. In the older adult age group, behavioral factors relating to comorbid depression, excess disability, pain, and sleep are of particular importance for behavioral medicine.

Outline

- Applying Behavioral Medicine to Older Adults

- Depression and Health in Older Adults

- Behavioral Sleep Medicine and Aging

- Chronic Pain Interventions for Older Adults

- Behavioral Medicine Issues in the Frail Old

- Summary

1. Applying Behavioral Medicine To Older Adults

Due to the twin factors of increased life expectancy and reduced birth rates, most nations throughout the world are experiencing a dramatic shift toward an older adult population. It is projected that by 2030, 70 million Americans (20% of the U.S. population) will be 65 years or older, compared to approximately 35 million (14%) in 2000. This aging revolution has led to increased public and scientific interest in how behavioral and psychological factors influence the aging process. In addition, with the great strides made in the successful treatment of acute illness in the past century, people are living longer but at the same time are accruing more age-related chronic illnesses. In response, the focus of the U.S. health care system is shifting toward managing chronic illness and disability, with an emphasis on maximizing independence and quality of life in late adulthood. The goal is to help people live well rather than simply live longer.

By necessity, the field of behavioral medicine will play an increasingly important role in the health care system of the future. Behavioral medicine encompasses the study of how behavior impacts the onset, progression, and recovery from illness and the application of those behavioral factors to promoting health and preventing illness. Older adults are in many ways the ideal age group to apply behavioral medicine principles and interventions. First, they are at much greater risk for chronic medical conditions, such as heart disease, lung disease, diabetes, cancer, and arthritis, and they often have multiple chronic conditions. Interventions aimed at preventing the onset or progression of such conditions are most cost-effective when they are designed for and delivered to this age group. In-home exercise interventions designed specifically for older adults, for example, have been shown to yield substantial benefits to patients with cardiovascular disease, partly due to the fact that older adults are more vulnerable to diminished cardiovascular capacity when they do not engage in systematic exercise.

Second, each chronic medical condition typically requires several different medications, multiplying the risk for side effects (e.g., memory impairment) and drug interactions. Accordingly, behavioral interventions that can manage symptoms without the use of medications are particularly important for this population.

Last, and perhaps most important, is the fact that physical and psychological conditions become more interdependent and reactive to each other with advancing age. Therefore, interventions aimed at psychological conditions, such as depression and anxiety, as well as the enhancement of psychosocial coping resources can have a significant impact on the physical health of older adults. Mind–body group interventions that teach a range of skills (e.g., relaxation training, problem solving, and cognitive approaches to managing stress) have been shown to be effective in enhancing coping and quality of life in older adults with chronic illness.

2. Depression And Health In Older Adults

The greater interplay between psyche and soma (body) in older adults is perhaps most evident in research on depression and health. When older adults have a depression overlaid on a medical condition, they are at much higher risk for excess disability. Excess disability is defined as a substantially lower than expected level of physical functioning for a given medical condition, attributable to behavioral factors (i.e., noncompliance and lack of activity). After a stroke or hip fracture, for example, when depression is detected an aggressive psychological intervention is required to prevent poor physical rehabilitation outcomes.

Even mortality has been shown to be affected by depression in older adults. In the Cardiovascular Health Study, depressive symptoms were related to 6-year mortality in a large sample of adults older than age 65, after controlling for medical and demographic variables known to affect mortality. The hypothesized mechanism by which depression affected mortality was decreased motivation to initiate and sustain cardiac health behaviors.

Unfortunately, medical professionals often fail to detect the presence of depression in older adults. This failure in detection is partly accounted for by the atypical presentation of depression in many older adults. One such presentation is as masked depression, which is characterized by the presence of more physical symptoms (i.e., reduced appetite, sleep disturbance, fatigue, and increased aches and pains) and fewer mood symptoms. Furthermore, depressed older adults are far less likely to have a negative view of themselves (e.g., ‘‘I am a failure’’ and ‘‘I am worthless’’), which is a hallmark of depression in other stages in life. Another presentation, called pseudodementia, is characterized by reversible symptoms of dementia (i.e., memory, attention, and other cognitive deficits) that are caused by an underlying depression.

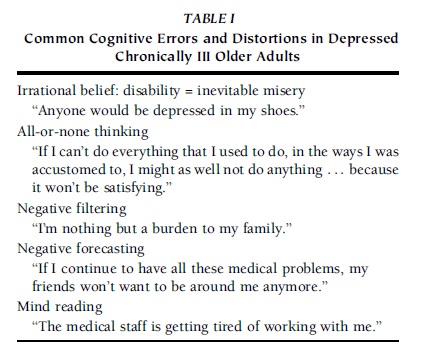

Fortunately, cognitive–behavioral and other psychotherapy treatment approaches have been found to be as effective as medication in the treatment of depression; moreover, older adults are as likely to benefit from these treatments as younger adults. Furthermore, there is no evidence to suggest that when chronic illness coexists with depression that psychotherapy treatment for depression is any less effective, although the situation is likely to contribute to the range of cognitive errors and distortions that need to be addressed in cognitive–behavioral therapy (Table I).

A positive development is a growing trend toward improved screening and treatment of depression in older medical patients as well as a greater presence of mental health professionals in primary care settings. This trend is particularly important given the fact that older Caucasian males are at the highest risk of any group for suicide and as many as 70% of suicide victims visit their primary care physicians prior to committing suicide. Tragically, these older male patients were unable to communicate their depression to their physicians and/or their physicians failed to ask the appropriate questions. Once depression is detected, psychotherapy that is provided on-site in a primary care office is often more acceptable to older adults. This detection treatment model highlights the importance of integrating mental health and medical treatment for older adults in particular.

TABLE I Common Cognitive Errors and Distortions in Depressed Chronically III Older Adults

TABLE I Common Cognitive Errors and Distortions in Depressed Chronically III Older Adults

3. Behavioral Sleep Medicine And Aging

Sleep has emerged as an important area in behavioral medicine. Treatment of insomnia, in particular, has been an important area of research and intervention because it is frequently caused or made worse by behavioral factors that are amenable to cognitive–behavioral intervention. In this case, again, the older adult population may be the ideal target group for these interventions.

There are numerous sleep disorders that increase in frequency with age, including sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, and periodic limb movement disorder, but chronic insomnia is the most prevalent in late life. The risk for developing chronic insomnia doubles between the ages of 55 and 85 and is present in 20–30% of the population older than age 65. It usually manifests itself as a combination of different problems, including difficulty falling asleep, excessive time spent in bed awake, more frequent and longer awakenings after sleep onset, and fewer total hours of sleep. Furthermore, there is an increasing recognition that sleep disturbance at night leads to daytime fatigue and/or sleepiness, which is associated with decreased quality of life in older adults.

During the past 30 years, several different behavioral interventions have been developed and shown to be highly effective. In fact, it has been noted that behavioral interventions for insomnia are probably the most effective and durable interventions in the behavioral medicine repertoire, with typical success rates after only six to eight sessions of treatment of 60% or greater. In addition, most of these treatment effects have been measured and sustained over periods of as long as 2 years.

The most effective cognitive–behavioral interventions tested to date include all or most of the following components: sleep hygiene instruction, relaxation training, sleep restriction, stimulus control, and cognitive modification. Sleep hygiene involves basic education on how the sleep environment, caffeine, alcohol, nicotine, food, and exercise affect sleep. Several different types of relaxation training (e.g., progressive muscle relaxation, deep breathing, and visual imagery) have been provided under the premise that mental and physical arousal that accompanies stress and anxiety will inhibit and disrupt sleep. If patients can train themselves to relax before sleep or at night after an awakening, they are more capable of falling asleep and staying asleep.

3.1. Sleep Restriction

Sleep restriction is the most difficult to adhere to but is probably the most essential component of treatment of insomnia in older adults. Its aim is to counter the sleep fragmentation and daytime sleeping that is commonly observed in older adults by restricting the time allowed to sleep to a specific ‘‘sleep window.’’ This sleep window is initially set for a very short period of time, determined by the average amount of time that the individual slept per night (based on a sleep diary that is kept throughout treatment). For many individuals, this period is 5 or 6 h long, so they are required to be awake for as many as 19 h each day prior to going to bed. During the first few weeks the individual experiences a high level of sleep deprivation, compounded by the fact that he or she is not yet capable of sleeping all the time during the sleep window. This prolonged sleep deprivation creates ‘‘sleep pressure,’’ which makes it easier for patients to train themselves to sleep without interruption during the sleep window.

After each week of sleep restriction treatment, the patient’s sleep efficiency (percentage of time slept during the sleep window) is calculated and 30 min is added to the sleep window if the patient achieves a sleep efficiency of 85% or greater. The eventual goal is to give the patient enough time in bed to meet his or her particular sleep needs (i.e., enough sleep to feel refreshed and not sleepy during the day) while maintaining a high level of sleep efficiency.

3.2. Stimulus Control

The stimulus control method is designed to increase the association between being in bed and being asleep. Predicated on operant learning theory, it involves instructing individuals to greatly limit their activities in the bed and bedroom. Basically, the only activities allowed in bed are sleep and sex. They are not permitted to do such activities in bed as watching television, reading, eating, worrying, listening to the radio, working, or simply resting. In addition, they are not allowed to be awake in bed for longer than 15–20 min at any time during the night, whether they are trying to fall asleep or trying to get back to sleep after awakening in the middle of the night or early morning. If they cannot fall asleep or back to sleep after 15–20 min, they are to get out of bed and engage in a nonstimulating activity until they become sleepy enough to try again. If they are unable to fall asleep again within 15–20 min, they are to repeat the same procedure. In addition, to facilitate the functioning of the body’s circadian clock system, they are instructed to use an alarm clock and get up at the same time every morning.

The final component of treatment is cognitive modification. Similar to cognitive restructuring for anxiety or depression, this approach emphasizes changing unrealistic beliefs and irrational fears involving sleep or sleep loss. Research shows that older adults with insomnia endorse stronger beliefs about the negative consequences of insomnia, express more fear of losing control of their sleep, and express more helplessness about its unpredictability compared to older adults without insomnia.

Dysfunctional cognitions about sleep create a vicious cycle by increasing performance anxiety about sleep, which in turn leads to arousal and greater difficulty falling asleep. Common misconceptions about sleep include the following: blaming daytime impairments, such as fatigue and inability to concentrate, exclusively on sleep loss; the fear that insomnia will worsen a medical condition; the belief that not getting 7 or 8 h a sleep per night will threaten one’s health; and the belief that sleeping late the next morning or napping is a good way to compensate for poor sleep at night. Finally, the belief that a bad night of sleep results in a ‘‘lost day’’ leads to cancellation or avoidance of activities, such as socializing and physical activities, that are important to maintaining health and promoting sleepiness at night.

Initially, the focus of research on behavioral treatment for insomnia was on younger adults and later it moved to older adults who had no other medical conditions. Until recently, individuals with chronic illness were excluded from these studies under the presumption that insomnia in these individuals was likely caused by a medical condition or a medication and therefore needed to be treated by directly managing the medical condition. However, it is now understood that insomnia in virtually all cases, regardless of coexisting medical conditions, is made worse by behavioral factors that are responsive to behavioral treatment. Indeed, two studies have demonstrated that older adults with multiple medical conditions are as responsive to treatment as individuals without medical conditions.

Insomnia in older adults occurs mostly in those with age-related chronic diseases, such as cardiac disease, arthritis, and lung disease. When insomnia coexists with chronic disease, these patients have significantly reduced quality of life, experience more pain, use more medical services, and are more likely to develop depression. Thus, providing behavioral treatment to ameliorate insomnia in these individuals has numerous benefits that go beyond improvement of sleep, leading to improved daytime mood, alertness, and physical functioning.

4. Chronic Pain Interventions For Older Adults

Another important application of behavioral medicine to the older adult population is the management of chronic pain. Pain is a constant factor in the lives of a great many older adults. Due to the greater prevalence of conditions that cause pain (e.g., arthritis and diabetes), older adults have more chronic pain and are more likely to have multiple sites of pain than younger adults. Pain in older adults has been strongly linked to excess disability, insomnia, depression, and increased health care utilization. Older adults with a combination of pain and depression have been shown to be particularly vulnerable to physical disability.

The two types of behavioral treatments for chronic pain that have been applied to older adults are cognitive– behavioral therapy (CBT) and operant conditioning. CBT methods focus on modifying beliefs, thoughts, attitudes, and skills that affect different aspects of the pain experience. They also employ relaxation training to reduce the sympathetic nervous system component of the pain experience. Operant conditioning focuses on modifying observable behaviors, such as activity level, medication usage, and pain signaling (i.e., grimacing, limping, and complaining). This method uses operant conditioning principles to reward activity, change environmental contingencies, and shift medication usage from an as-needed to a time-contingent approach. Both treatment methods use learning techniques such as consistent self-monitoring, graded practice, and homework. CBT and operant techniques are compatible and are often used together in clinical practice.

Contrary to traditional bias among professionals that older adults may not benefit from CBT interventions due to the introspection that is involved, studies demonstrate that older adults obtain equal benefits from CBT pain interventions compared to younger adults. In addition, they are no less likely to drop out of treatment. Older adults have also been shown to be as capable of learning relaxation procedures as younger adults. Nonetheless, research exploring age bias in inpatient and outpatient pain treatment programs has found that rehabilitation professionals remain less confident that older adults will benefit from their program. This bias is confirmed by the much smaller than expected percentage of older adults enrolled in these programs, which means they are being underserved by these invaluable treatments.

Older adults may also have some unique, age-related strengths and resources that help them cope better with pain. The majority of studies suggest that older adults have a higher pain threshold compared to younger adults. In addition, older adults may be more tolerant of pain due to the fact that they are more willing to accept certain levels of pain and discomfort as a part of growing older. This is consistent with studies showing that older adults report diminished emotional responses to pain, such as depression, anxiety, anger, or fear. Similarly, according to the life span theory of control, as individuals move into late adulthood there is a shift from a focus on primary control (control over the external world) toward an emphasis on secondary control (control of the internal mental and emotional life). This may equip older adults with a greater skill to cope with stressors that are irreversible or cannot be easily controlled, such as chronic pain.

5. Behavioral Medicine Issues In The Frail Old

Among the old-old (age 85+ years) with significant medical illnesses, sometimes called the frail old, behavioral medicine has perhaps an even greater role to play due to the even stronger interplay between psyche and soma. When the frail old develop new medical problems that compound existing ones, they often experience the onset of new psychological symptoms, such as delirium, depression, or paranoia. Similarly, older adults residing in nursing homes have been shown to experience increased mortality and medical illness, not accounted for by medical factors, when they are required to relocate from one institutional setting to another. Even ‘‘timing of death’’ research has shown that, remarkably, the old-old are more likely to die of natural causes after, rather than before, a holiday or important family event. This suggests that the psyche exerts some degree of control over the timing of death. When frail older individuals are hospitalized they often experience depressed psychophysiologic functioning in the form of increased incontinence, confusion, agitation, and loss of appetite. These complications lead to further medical interventions, such as catheterization for incontinence, the administration of sedating medications or use of restraints for agitation, or tube feeding in the case of failure to eat. These treatments, in turn, lead to iatrogenic effects (i.e., complications from treatment) such as bladder infections (from catheterization), blood clots (from being restrained to the bed), and pneumonia (from tube feeding).

6. Summary

Due to the increased risk of chronic illness and the increased interaction between psyche and soma in late life, behavioral medicine interventions that target older adults are among the most cost-effective and essential. Interventions that reduce anxiety and depression or enhance coping in older adults with chronic diseases have much potential to yield crossover effects on medical variables, such as functional status, symptom severity, and cognitive functioning. These factors combined with the aging revolution in the United States will lead to an increased focus within behavioral medicine on providing services to older adults.

References:

- Rybarczyk, B., Gallagher-Thompson, D., Rodman, J., Zeiss, A., Gantz, F., & Yesavage, J. (1992). Applying cognitive–behavioral psychotherapy to the chronically ill elderly: Treatment issues and case illustration. International Psychogeriatrics, 4(1), 127–140.

- Schulz, R., Beach, S. R., Ives, D. G., Martire, L. M., Ariyo, A. A., & Kop, W. J. (2002). Association between depression and mortality in older adults: The Cardiovascular Health Study. Archives of Internal Medicine, 160(12), 1761–1768.

- Stepanski, E., Rybarczyk, B., Lopez, M., & Stevens, S. (2003). Assessment and treatment of sleep disorders in older adults: An overview for rehabilitation psychologists. Rehabilitation Psychology, 48, 23–36.

- Yonan, C. A., & Wegener, S. T. (2003). Assessment and management of pain in the older adult. Rehabilitation Psychology, 48, 4–13.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.