This sample Sexual Dysfunction Therapy Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of psychology research paper topics, and browse research paper examples. This sample research paper on Sexual Dysfunction Therapy features: 6000+ words (21 pages), APA format, an outline, and a bibliography with 5 sources.

Sexual dysfunction has been classified according to the four phases of sexual activity in both males and females. At each stage the individuals can suffer from high or low levels of activity and additional physical problems and pain at various stages during these phases.

Outline

I. Introduction

II. Classification of Sexual Dysfunction

III. Principles of Sexual Dysfunction Therapy

IV. Physical Therapies

A. Oral Medication

B. Intracavernosal Injections

C. Artificial Devices

D. Surgical Procedures

E. Prosthesis

F. Inflatable Prosthesis

V. Psychological Therapies

VI. Ethical Issues

VII. Prognosis

VIII. Special Groups

A. Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Adults

B. Older Adults

C. Ethnic Minorities

D. Those with Disability/Chronic Physical Illness

E. HIV/AIDS

F. Paraphiliacs

IX. Conclusions

I. Introduction

Sexual dysfunction and its treatment have been well described in historical, medical and psychiatric texts. The presentation of patients with sexual dysfunction to clinicians is determined by social norms, mores, and expectations. In societies and cultures where sex is seen as a purely procreative process, people are less likely to present with sexual dysfunction—especially if the dysfunction is not interfering with procreation. On the other hand, in societies where sexual satisfaction is seen as a personal pleasure and fulfillment, more people are likely to seek help with the slightest dysfunction.

The more severe the problem, the more likely it will be that the individuals seek therapeutic intervention. If there is stigma attached to sexual inadequacy in a society and the individuals believe that they are going to see a mental health professional, it is more likely that their attitudes may well produce a scenario where the pressure is on them and the therapist to do something about the problem furtively and quickly. The decision to seek professional help is very difficult for most people. Under the circumstances, the first impressions of the therapist and his/her response to the problem will be of paramount importance. An additional problem that the individuals may bring with them is an underlying relationship difficulty. A further complication is that the individual’s demand may be for physical treatments and not for psychological therapies.

II. Classification of Sexual Dysfunction

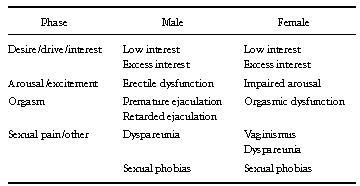

The problems of classification in psychiatry are many, and these are reflected in the classification of dysfunction (see Table I). Such a simple division has its advantages, but it does not take into account any underlying causative factors that would need to be taken into consideration while planning any therapeutic interventions. Precise labeling of the problem often ignores the relationship, cultural, and physical contexts. In addition, the physical causation of sexual dysfunction may be either central—in the brain, or peripheral— in the genitourinary system. There may be an underlying biological substrate and there may be biological abnormalities, but on their own these may be insufficient for a full understanding of the disorder in question. The International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV), the two principal classificatory systems around the world, use a categorical classification and, apart from minor differences, are broadly similar in their approaches to diagnosis, including a multi-axial approach.

Table I. General Classification of Sexual Dysfunction

Female sexual dysfunction includes sexual desire disorders along with impaired arousal, orgasmic disorder, and vaginismus. Females may perceive their sexuality differently, and their sexual activity is, in part, culturally defined. This definition impacts upon the way in which women understand their own sexuality and whether they can adjust their expectations of their sexual functioning. Female sexual dysfunction may be due to early childhood experiences, or to later trauma, including sexual abuse, childbirth, and infertility, among others. Myths about sexual activity and sexual functioning may well affect both males and females.

In males, while orgasm and emission are normally linked, they can be separated, because in the latter phase organic muscle contraction and emission are responsible for ejaculation. Male sexual dysfunction includes premature ejaculation, retarded ejaculation, painful ejaculation, and erectile difficulties. The latter could be linked with Peyronie’s disease.

Various psychological factors that contribute to sexual dysfunction in both males and females include anxiety, anger, and ‘‘spectatoring,’’ and these may result from misunderstandings and ignorance, unsuitable circumstances, bad feelings about oneself, one’s partner, or the relationship, as well as poor communication within the relationship. A psychosomatic circle of sex that links cognitions with awareness of response leading on to peripheral arousal and genital response on the one side and activating the limbic system and spinal centers to orgasmic conclusion on the other is often used to describe various etiological points that may contribute to precipitation and perpetuation of sexual anxiety and sexual dysfunction. Thus, a complex set of factors is usually involved.

III. Principles of Sexual Dysfunction Therapy

After assessment of the exact nature of the dysfunction and possible etiological factors, two basic steps mark the early stages of therapy: managing anxiety and education. Quite often, the partners find it difficult to discuss sexual problems with each other or with the therapist, and the underlying lack of sexual education may well contribute to this and to sexual anxiety. Simple reading materials often allow the therapist to discuss problems, offer solutions, and peg the treatment planning. This basic education is often crucial in sex therapy.

Anxiety management is usually carried out in a number of ways—from physical muscle relaxation to yoga training or using tai chi or the Alexander technique. A valuable part of this anxiety management is the process of ‘‘despectatoring,’’ which encourages individuals to get away from focusing on the sexual act and instead allowing relaxation in their physical and intimate contact. If the therapist discovers that there are underlying angry or depressive feelings, these may need to be treated medically or with psychological interventions. Bad feelings about sex, oneself, or one’s partner need to be aired and discussed at length. If there is any underlying relationship discord, it would need to be assessed and managed. Sometimes this work may need to precede sexual dysfunction therapy.

The principles of managing sexual dysfunction from a psychological perspective are described in detail below. In the first instance, it is necessary to deal with physical management of sexual dysfunction.

IV. Physical Therapies

There are at least four physical methods—oral medication, intrapenile injections, artificial devices, and surgical procedures. Physical methods are mostly used for treating male patients.

A. Oral Medication

Yohimbine has been shown to be an effective drug in managing erectile difficulties. It works better than placebo and is an a-2 adrenergic receptor blocker. Idazoxan is another selective and specific a-2 adrenoceptor antagonist and works in some cases, although it tends to have more side effects. The heterogeneity in etiology makes the existing clinical trials difficult to interpret.

B. Intracavernosal Injections

Phenoxybenzamine hydrochloride, papaverine hydrochloride, phentolamine mesylate, and prostaglandin-E have been used as intracavernosal injections for erectile difficulties. Phenoxybenzamine usage had led to priapism or painful erections lasting for up to 3 days and has largely fallen into disuse. Papaverine hydrochloride is a smooth muscle relaxant that, when injected intracorporeally, will result in active arterial dilation, corporeal smooth muscle relaxation, and venous outflow restriction—thus producing an erection. It is also less painful to inject, and these injections produce erections that are less painful and last for a few hours generally, at the maximum. A mixture of papaverine and phentolamine has been shown to be superior to papaverine alone.

Such vasoactive substances are also used to diagnose erectile problems, and evaluate indications for surgery of Peyronie’s disease. In treatment, they are used for occasional self-injection and for regular self-injection in cases of persistent erectile failure. It has been shown that patients, having obtained erections with injections initially, often go on to have spontaneous erections.

The cases most likely to respond to this form of treatment are: mild cases of arteriogenic etiology, all cases of neurogenic etiology, mild cases of abnormal leakage, and those who have had unsuccessful surgical procedures. Some cases of psychogenic etiology also respond well to it.

The dosage of the drug papaverine should be increased gradually. In the first instance, from 8 to 15mgs should be used and usually this amount is sufficient to produce a slight enlargement of the penis lasting for 15 minutes or so. At subsequent consultations, higher doses may be used until the optimum dose is reached (leading to an erection of good quality (9 out of 10 or better) lasting for perhaps 30 minutes). There is still a lot of variation in individual responses so it is essential that individual doses are determined slowly and carefully. If a mixture of phentolamine and papaverine is used, the first trial dose of papaverine is limited to 15mg. If the response is poor, then a further injection of 0.5 mg phentolamine is given. In subsequent visits, a mixture of 0.5mg phentolamine and 30 mg papaverine is used, going up to a maximum recommended 2 mg phentolamine and 60 mg papaverine. These injections are usually given at the base of the penis at 3 o’clock or 9 o’clock positions (posterolaterally)— away from neurovascular bundle and urethra— using an insulin syringe and a gauge 26 or 27 needle. After cleaning the skin, holding the syringe perpendicular to the penis, the physician on the first occasion, and the patient himself subsequently (or his partner), inserts the needle through the tough tunica albuginea into the left or right corpus cavernosum. As the resistance is overcome and the needle enters the tunica a sensation is experienced at which point the medication is injected. If phentolamine is used first, the injection should be given with the patient lying flat as postural hypotension may occur if there is a leak into the venous system. The patient may then stand and an erection will appear in 10 to 20 minutes. The couple may be taught the technique together, and some patients prefer their partner to do the injecting as part of their foreplay. The patient should be advised not to use injections more than twice a week with a 2-day interval at least. Erectile capability may well return after some months of self-injection treatment. If the injection of papaverine and a combination with phentolamine fails to produce an erection, the possibility of a venous leak must be investigated.

In the United Kingdom in recent years, prostaglandin E has been used in the same way as papaverine and phentolamine but the patient needs to learn to dissolve the powdered compound for injection. The starting dose is 5 to 10 micrograms, with a maximum of from 20 to 40 micrograms. There is some clinical evidence to suggest that this preparation is more effective than papaverine alone and has a lower incidence of priapism or prolonged erections. In some cases, however, the patient may experience pain in the shaft or the glans following the injection.

Cardiovascular problems need to be investigated thoroughly prior to commencing treatment. Severe liver dysfunction, severe substance misuse, allergic reactions, and a history of sexual offending are some of the other contraindications. The most serious side effect is priapism. Other side effects described include painful nodules in the penis, fibrotic nodules, liver damage, pain, infection at the injection site, and bruising. Between 2 and 15% of patients will develop priapism. When this happens, the patient is advised to go to the nearest emergency room to have blood withdrawn from the corpora, and metaraminol (2mgs) or adrenaline (20 micrograms in 0.1 ml) injected at the base of the penis to be repeated half an hour later if indicated. In rare cases, surgical intervention may be indicated.

Using written information sheets and audiovisual aids to inform the patients and their partners, including advice on what to do if priapism occurs, should be encouraged. Written consents are recommended. Ethically, there remain several issues in offering physical treatments where underlying causes may well be psychogenic and the focus of the relationship appears to be on the erection rather than on more general factors. There is no doubt that, in some cases, the quality of the relationship following an improvement in sexual satisfaction due to frequency of intercourse increases intimacy and sexual arousal.

C. Artificial Devices

In 1917 Otto Lederer first patented a vacuum pump that induced erection by creating a vacuum around the penis, and maintained erection by the use of a constriction ring around the base of the penis. The different devices tend to vary according to the use of a pressure-limiting device, the shape of the cylinder, the design of the tension rings, and external versus attached pumps.

The basic mechanism of action is the filling of the corpora cavernosa due to suction and venous stasis, secondary to constriction, which are both passive mechanisms. As the additional volume can only be maintained by the use of the constriction device at the base of the penis, the patient and his partner often find it very difficult to deal with, when compared to papaverine injections. Furthermore, in this method, skin temperature of the penis falls and the erection is often not very strong. The commonest device in use is a rigid tube made of plastic, which is connected to a hand pump at one end and an opening at the other through which the flaccid penis is inserted. Prior to this, the penis and the tube are well lubricated and a rubber constriction band is placed around the open end of the tube. When the pump is used, air is pumped out and the resulting negative pressure draws blood into the corpora, producing an erection. Following this, the constricting rubber band can be slipped off to place it at the base of the penis to limit venous outflow. This band can be left in situ for half an hour. Another appliance—Correctaid—works on the same principle but the condom-shaped device is made of transparent silicon rubber. A tube is passed through at its base to open the inside of the tip of the sheath. The device is worn over the penis. Yet another appliance is the Blakoc suspensory energizer ring, which is rectangular and is made of ebonite, which can be fitted around the base of the penis and under the scrotum. With its small metal plates it can have some stimulatory effect on the erectile mechanism. The success rates using vacuum devices are variable. The side effects include hematoma, pain, ecchymosis, numbness, painful or blocked ejaculation. As in injection therapies, spontaneous erectile activity may return with the use of vacuum devices as increased self-confidence reduces performance anxiety.

D. Surgical Procedures

Surgical revascularization and surgical implants have been tried. Pre-operative counseling, education, and adequate preparation for the surgical procedures and informed consent with some risk /benefit analysis are essential. Originally, arterial bypass was attempted to join the epigastric artery into the side of the corpora cavernosa. Other attempts have included utilizing saphenous vein bypasses from the femoral artery to the corpora, and saphenous vein bypass from the inferior epigastric artery to the corpora cavernosa. The best results are said to be in younger males, although most authorities will agree that the theoretical disadvantages associated with these surgical procedures are genuine. The epigastric artery-dorsal artery revascularization is said to be more advantageous.

The selection of patients for sexual surgery is problematic because of significant areas of disagreement on the indications and the success criteria of various procedures. In spite of surgical intervention, underlying psychological factors often need to be taken into account. Some of these have been identified as poor sexual communication, lack of foreplay, and loss of interest. Preoperative counseling as part of the assessment should help in ruling out some of these problems.

E. Prosthesis

The use of plastic splints for the penis was first described in 1952. Semi-rigid silastic rods result in an almost permanently erect penis which can be bent to different angles. Acceptability of these processes has been improved by using modified appliances. An inflatable penile implant has been used to provide improvements in both girth and rigidity. Such a device works on a fluid-filled system that allows the flaccid and erect penis to appear normal. The choice between semirigid or inflatable devices depends very much on the patient’s and his partner’s preferences.

The semirigid prosthesis is made of medical grade silicone rubber with a sponge core. The device may be implanted by using perineal approach to insert it in the corporeal bodies. The device is available in lengths of 12 to 22cm, and diameters of 0.9, 1.12, and 1.3mm. A flexirod prosthesis differs from the above by having a hinged area that enables the phallus to be placed in a dependent position when not being used for intercourse. The diameters here range from 0.9 to 1.2 cm and the length from 7 to 13 cm, and it can be shortened if necessary. Another type of prosthesis (called the ‘‘Jonas prosthesis’’) is used commonly and can be inserted through subcoronal, midshaft, penoscrotal, and suprapubic approaches, as well as through the perineal approach. In addition, it has 3 diameters of 9.5, 11.0, and 13.0 mm, and lengths of 16 to 24 cm. It is malleable and thus the penis can maintain a dependent position as well as an upright one. Variable versions of this prosthesis are now available. A newer prosthesis on the market is made of fabric-wrapped stainless steel that has flexibility of size and positioning.

F. Inflatable Prosthesis

As mentioned above, the inflatable prosthesis in its initial model consisted of an inflate pump, a deflate pump, a reservoir, and paired inflatable penile cylinders. However, the inflate and deflate pumps have been combined into one mechanism, and the original six segments of silicone rubber tubing have been reduced to three. The inflatable prosthesis has the advantage of being cosmetically appealing, it conforms to the patient’s own corporal anatomy, and the erosion of the prosthesis through the glans is unlikely. Its side effects include aneurysm formation, high mechanical failure rate, kinking of the tubes, infection, puminosis, and scrotal hematoma. The age of the patient, coexisting medical problems, patient preference, and the risk of complications are some of the factors that need to be taken into account when a decision is being considered.

V. Psychological Therapies

There is a great deal of literature on the psychological approaches to the treatment of sexual dysfunction. Many authorities consider psychological therapy as the treatment of choice when help is sought for sexual dysfunction, although obviously there are instances where a physical approach might be more appropriate.

Psychological therapies take different forms. Psychodynamic therapy aims to understand the presenting problem as a manifestation of an underlying, unconscious conflict or memory, and it is often assumed that this has its origins in childhood. The therapy takes the form of a verbal, interactive endeavor, which also uses the transference (emotional responses of the patient to the therapist) as a means of resolving problems. Psychodynamic therapy for sexual dysfunction has not been adequately evaluated. There is a practical problem, too, in that such therapy is quite time consuming. However, there are circumstances when such an approach may be appropriate.

The more widely used psychological therapies for sexual dysfunction are best described as behavioral, although in recent years cognitive approaches have also been added.

In the behavioral approach, the treatment is directed toward the sexual problem itself. An important element of this is the reduction of anxiety, as in most cases anxiety acts as a factor that perpetuates the dysfunction. The more one fails in sex, the more anxious one gets. One tends to become a ‘‘spectator’’ of one’s own performance, thus inhibiting spontaneous sexual responses and sexual enjoyment. Hence, in therapy the reduction of anxiety becomes a major priority. Early behavior therapists like Joseph Wolpe used this approach in the treatment of sexual problems. He used a method that he called ‘‘systematic desensitization,’’ in which the sexual problem was dealt with in graded, nonthreatening stages. As a first step, the couple were asked to refrain from intercourse, but to engage in other intimate behaviors, mainly touching and caressing, in a gentle, step-by-step way. In this fashion, anxiety could be overcome gradually, and full sexual functioning restored. This basic behavioral approach was followed by a more formal, essentially behavioral, treatment package developed by William Masters and Virginia Johnson—universally known as the ‘‘Masters and Johnson approach.’’ In this, after the assessment, the couple are asked to agree to a ban on intercourse, and they are then given detailed instructions in graded sexual exercises. The first stage is touching and caressing, excluding the genital area and the woman’s breasts; this is called ‘‘nongenital sensate focus.’’ After some practice sessions of this, which the couple carry out at home, they move on to the ‘‘genital sensate focus’’ stage, where the genitals and the breasts are not excluded. In these stages, the couple are also encouraged to engage in enhanced communication, both verbal and nonverbal. After the second stage, specific additional behavioral strategies are used, to deal with whichever specific problems the couple have presented with. Examples are the ‘‘squeeze’’ technique for premature ejaculation, ‘‘overstimulation’’ for retarded ejaculation, and the use of graded dilators in the treatment vaginismus. In erectile difficulties, a ‘‘teasing’’ approach may be used, enabling the male to learn to defocus on the erection and to relinquish control.

The principles of the Masters and Johnson approach can also be used with patients who do not have partners, with certain modifications. In the early stages, they are usually asked to engage in ‘‘self-focusing.’’

Relaxation strategies are often taught to the patients in both couple and individual therapy as an additional technique for reducing anxiety and tension. This is usually done at an early stage.

This basic behavioral approach is often augmented by cognitive interventions. This involves identifying those cognitions that the patient may have that are faulty or dysfunctional. Such dysfunctional cognitions (thoughts, beliefs, attitudes) are often major factors in the etiology and more commonly of the perpetuation of sexual dysfunctions. They include cognition like ‘‘I am sure to fail again,’’ ‘‘If I do not get an erection, my partner will ridicule me,’’ and ‘‘It is going to be painful again.’’ The therapist elicits such cognitions from the patient as part of the assessment, and then works on modifying these, using techniques of cognitive therapy (such as creating situations where they are shown to be false, and pointing out their self-fulfilling nature).

In the practice of psychological therapy, behavioral and cognitive elements are often used in conjunction; hence the term ‘‘cognitive-behavior therapy,’’ which many therapists these days use to describe what they do. Cognitive techniques are particularly applicable for those without partners, who tend to avoid developing relationships because of fear of repeated failure.

In recent years, this basic psychological approach has been extended to include a systemic dimension. The sexual dysfunction is viewed in the context of the overall relationship of the couple. Relationship factors such as jealousy, resentment, and dominance often contribute to sexual problems, and the therapist takes these into account and intervenes appropriately. These systemic interventions can be, and often are, undertaken within the context of an overall behavioral framework. There is evidence that this expanded approach is rapidly gaining popularity among therapists who specialize in the psychological treatment of sexual dysfunction.

Group approaches are also used in this field. Therapists sometimes run groups for patients without partners, or even see couples in groups. In these, much cognitive work is done in the group setting, and in addition behavioral exercises are discussed and outlined, which the patients would implement as homework. Sometimes, those in group therapy are given brief individual or couple sessions with the therapist as an additional measure.

The original Masters and Johnson approach always used a team of two therapists, one male and one female, with every couple. In the practice of sexual dysfunction therapy today, this is the exception rather than the rule. In most instances, one therapist sees the couple, or the individual who has no partner, for regular sessions.

It was noted above that a psychodynamic approach is useful in certain circumstances. There are instances where the behaviorally based treatment may lead to some improvement, but progress reaches a plateau. It is considered useful, in these circumstances, to explore intrapsychic factors that may be relevant to the problem. Such exploration is usually undertaken within a psychodynamic framework. Early memories, conflicts, and so on, that may have contributed to the problem, and/or unacknowledged current psychological factors, are explored and, where possible, resolved.

VI. Ethical Issues

If the couple perceives the male erectile dysfunction as the only problem and the focus is on obtaining erections without looking at underlying problems, ethical dilemmas are raised for the therapist. Equally, if a child molester presents for therapy for sexual dysfunction, there is a clear and serious dilemma for the therapist. It is possible that under these circumstances the patient may not divulge his complete history. The forensic aspects of the underlying problems will need to be taken into account as part of the assessment. When couples are about to break up and the underlying sexual dysfunction tends to take on a greater importance, the couple’s energies may be focused on the sexual problem rather than on the relationship itself. Often the patients, their partners, and some therapists may see psychological treatments as time consuming and prolonged, painful experiences, whereas physical treatments may be more appealing. Physical treatments should be offered only after a thorough investigation of the dysfunction, and treatment should not be employed simply to fulfill the patient’s or their partner’s unrealistic dreams of the ‘‘ever-ready potent man.’’

VII. Prognosis

Prognosis of sexual dysfunction varies according to the type of dysfunction. The literature on sex therapy indicates that prognosis in general depends on a number of factors. One is the motivation of the patient / couple. A good overall relationship is also associated with a good outcome. Concurrent psychiatric disorder is a hindrance to good progress. While the different disorders have varying degrees of success, the prognosis for vaginismus is probably the most positive. In female orgasmic dysfunction, it appears that younger patients do better in treatment.

VIII. Special Groups

A. Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Adults

These three groups present with the same varieties of sexual dysfunction discussed above, and the treatment plans, whether physical or psychological, are about the same. However, there are some additional factors that need to be taken into account. The first of these is the fact that, even though a gay or lesbian individual is seeking help, this does not necessarily mean that they are publicly ‘‘out’’ and that everyone knows of their sexual orientation. A second factor is the common use of high-tech sex toys, pornography, and in men, ‘‘fist-fucking,’’ sadomasochistic practices, and water sports (urination). Lesbians, on the other hand, may well have feminist views and may have political views on sexual intercourse that may appear to be at odds with those of the therapist. Furthermore, views on pornography, sexual exploitation, and the existence of a patriarchal society may well contribute to models of behavior and expectations of treatment at variance with those of heterosexual women.

Some additional issues in working with these three groups include problems of society’s widely held homophobic views and practices, the individual’s internalized homophobia, and difficulties inherent in same-sex relationships. On the other hand, same-sex couples have the advantage of not being bound by opposite sexual role expectations, for example, the male must always initiate, and the female must be submissive. Gay men and lesbians tend to have a more varied sexual repertoire, and penetration is not the main focus of the sexual activity. The relationships may be open and nonmonogamous. The therapist’s views on nonmonogamy and knowledge of the gay subculture may prove to be of great relevance for the success of therapy. The therapist must inquire closely about the development of sexual identity, detecting discrepancies in sexual orientation in the two partners, identifying the problem areas in the relationship and then setting up appropriate intervention procedures.

Bisexual individuals may feel unable to bring either partner, and their problems may be with one gender or the other. The nonheterosexual orientation must be seen as equal but different, and the clinician must be familiar with group subcultures. Sexuality carries different meanings for gay men and lesbians and bisexual individuals, and these need to be ascertained and the emphasis on nonpenetrative pleasure encouraged.

B. Older Adults

Both therapists and patients need to question their assumptions about aging adults. There is some truth in the observation that desire for sexual intercourse falls off with age. However, ageist views on the clinician’s part do not help the process of therapy. Older adults may change their practices and become more interested in nonpenetrative sexual activity. In addition, the loss of a partner may be more likely and newer relationships may have the additional burden of opprobrium by the extended families. Female and male sexual responses change with aging, usually due to hormonal changes. Whereas a young male may achieve a full erection in a matter of seconds, an older man may require several minutes to achieve the same response. He may also require a lot of physical stimulation to achieve an erection. Seminal fluid may be decreased. In addition, physical debility may contribute to lowered sexual interest and physical functioning. Drugs prescribed for physical conditions may also lead to impaired sexual functioning. Various psychological factors affecting sexuality in the elderly include lack of partners, lack of interest, and social stigma regarding older individuals ‘‘indulging’’ in sex. The therapist needs to be aware of the three fundamental areas of biological changes, attitudinal factors, and the role of life events. Pain, dryness, hot flushes, and physical mobility problems, especially those due to medical conditions like arthritis, are common and the therapist needs to deal with these. In this age group greater care must be taken to exclude physical causes of dysfunction. Psychological and physical therapies can be used in the same way as in younger adults, bearing in mind the essential factors specific to the older adult as highlighted above.

C. Ethnic Minorities

Various ethnic minorities have different cultural values placed on sex and sexual intercourse. As mentioned earlier, if the culture sees sexual intercourse as procreative and not for pleasure, the presenting complaint may be an inability to conceive rather than lack of pleasure. In cultures where semen is considered highly important and valuable, the individual may well have difficulties with suggestions of masturbation, sensate focus activity, and so on, as recommended by the therapist. In some cultures, various sexual taboos may well contribute to the anxiety that the couples experience. Under these circumstances, it would be useful to include this as part of the assessment and to ensure that appropriate therapeutic measures are taken. In some communities, the underlying causation of sexual dysfunction is generally seen as physical rather than psychological, and the patients and their partners may refuse to consider psychological intervention and demand physical treatments only. Under such circumstances, the therapist needs to be innovative in planning and delivering a combination of treatments. Using yohimbine or other physical agents in combination with a psychological approach can be fruitful. The therapist needs to be aware of the cultural nuances and social mores as well as cultural expectations in order to deal with sexual dysfunction problems satisfactorily.

D. Those with Disability/Chronic Physical Illness

Not only do certain chronic physical illnesses such as autonomic neuropathy, damage to nerves, and neurotoxic chemotherapies produce problems with sexual functioning, many drugs that are used for these conditions also contribute to sexual dysfunction. Cardiovascular disease, cancer, arthritis, and so on, increase with aging, and chronic pain may further contribute to low sexual interest and orgasmic dysfunction. A thorough physical assessment must be an integral part of the assessment of sexual functioning. A number of patients may simply be seeking reassurance, education, or permission to carry on with their sexual activity, and a significant proportion may benefit from very simple and focused counseling or intervention. However, in some cases more prolonged therapy may be needed. In a majority of cases, education to change attitudes is a crucial part of therapy. Such an attitude change can be fostered by using a mixture of written and/or audiovisual materials and cognitive methods to combat false beliefs and to deal with inappropriate and handicapping worries. Overcoming physical handicaps along with working on relationship problems may mean that the goals of sex therapy need to be changed and appropriate interventions put in place. Physical treatments need to be combined with sex therapy. The goals of treatment may be limited by the physiological impact of the disease or disability. However, enhancing sexual functioning and enjoyment is generally achievable.

E. HIV/AIDS

The AIDS epidemic has contributed to a change in patterns of sexual activity not only in gay and bisexual communities, but to some degree in the heterosexual community as well. AIDS has also affected how people view their sexuality. In clinics, HIV-positive patients not infrequently present with sexual dysfunction. When dealing with such patients the therapist needs to establish their views on the illness, their knowledge about the illness as well as sexual dysfunction, and their attitudes toward therapy. There is no doubt that HIV-positive individuals can be helped using similar models of therapeutic intervention as those used with others, even though some therapists may find recommending physical interventions like penile prosthesis difficult. A thorough clinical assessment will allow the therapist to deal with some of these difficulties.

F. Paraphiliacs

Those with paraphilias, or variant sexual desires and practices, sometimes present with sexual dysfunction. Paraphiliacs seeking treatment in this way are almost always male, reflecting the vast preponderance of males over females among paraphiliacs. In their presentation, they often complain of difficulties in nonparaphiliac sexual relationships. For example, a man with a strong shoe fetish might seek help for an inability to obtain or maintain an erection in sex without contact with a woman’s shoe. These patients need to be assessed carefully, and individually tailored treatment needs to be considered. The aim should be, as far as possible, to incorporate the paraphilia in a limited, controlled way into the person’s sexual repertoire. Needless to say, criminal paraphilias such a pedophilia or zoophilia, or any paraphilia that the patient’s partner finds intolerable, cannot be considered for such incorporation. In such cases, help should be directed toward the control of the person’s paraphiliac urges. Various psychological techniques are available for the control of paraphiliac desires and behaviors— for example, orgasmic reconditioning and covert sensitization. At the same time, help should also be given to reduce any anxiety about nonparaphiliac sex, and to build up skills and competencies needed for such activity. In other words, a multifaceted treatment program is often required.

It is also important to note that little can be achieved in the treatment of paraphiliacs unless the patient has motivation and is cooperative.

IX. Conclusions

Sexual dysfunction therapy is widely practiced today, and many mental health professionals offer this service. Recent years have witnessed several major developments: new physical treatments for males, the use of cognitive therapy principles where needed, the combination of cognitive-behavioral treatment with a systemic approach, and the recognition of cultural differences. The demand for sexual dysfunction therapy is high, and more training is needed in this area within the mental health professions. Where competently used, on the basis of careful assessment, the therapy helps many patients and couples make significant improvements. Needless to say, further research is needed into the treatment techniques as well as into the dysfunctions themselves. One can expect further major progress in several areas in the next few decades.

Bibliography:

- Bancroft, J. (1989). Human sexuality and its problems (2d ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

- Hawton, K. (1992). Sex therapy: For whom is it likely to be effective? In: K. Hawton & P. Cowen (Eds.), Practical problems in clinical psychiatry. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kaplan, H. S. (1995). The sexual desire disorders: Dysfunctional regulation of sexual motivation. New York: Brumner/Mazel.

- Rosen, R. C., & Leiblum, S. R. (1992). Erectile disorders: Assessment and treatment. New York: Guilford Press.

- Wince, J. P., & Carey, M. P. (1991). Sexual dysfunction: A guide for assessment and treatment. New York: Guilford Press.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.